Mapping Worldwide Antibiotic Use in Dental Practices: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

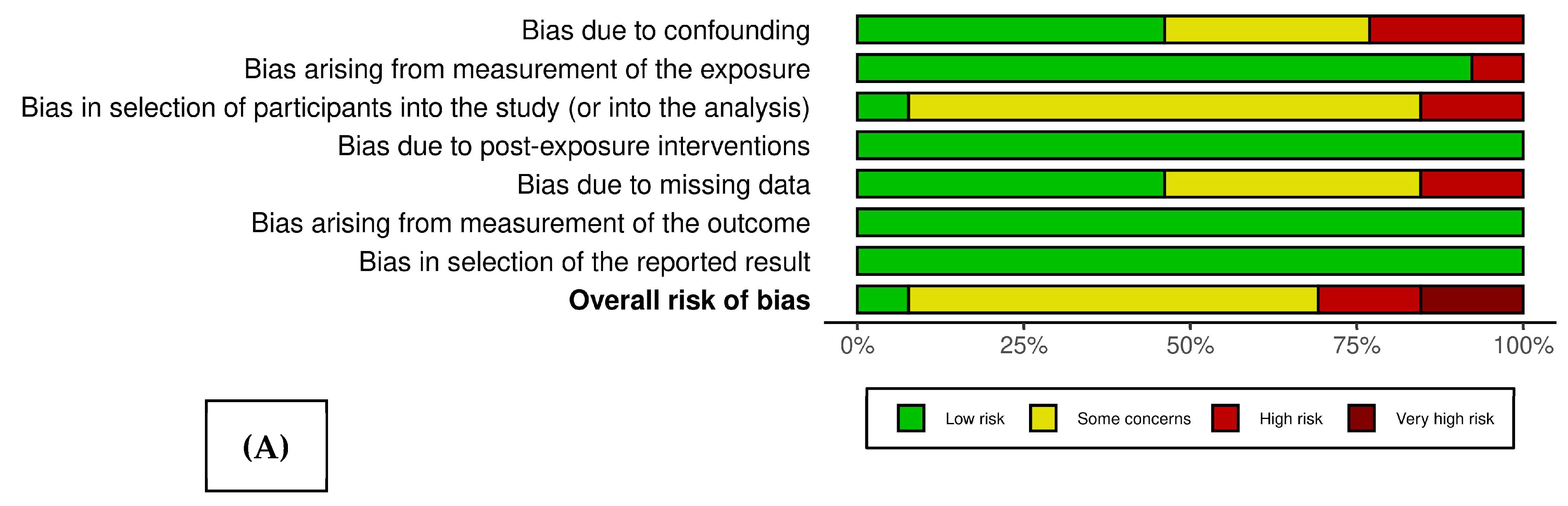

2.1. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

2.2. Detailed Extracted Data

2.3. Most Prescribed Antibiotics by Dentists in Each Country

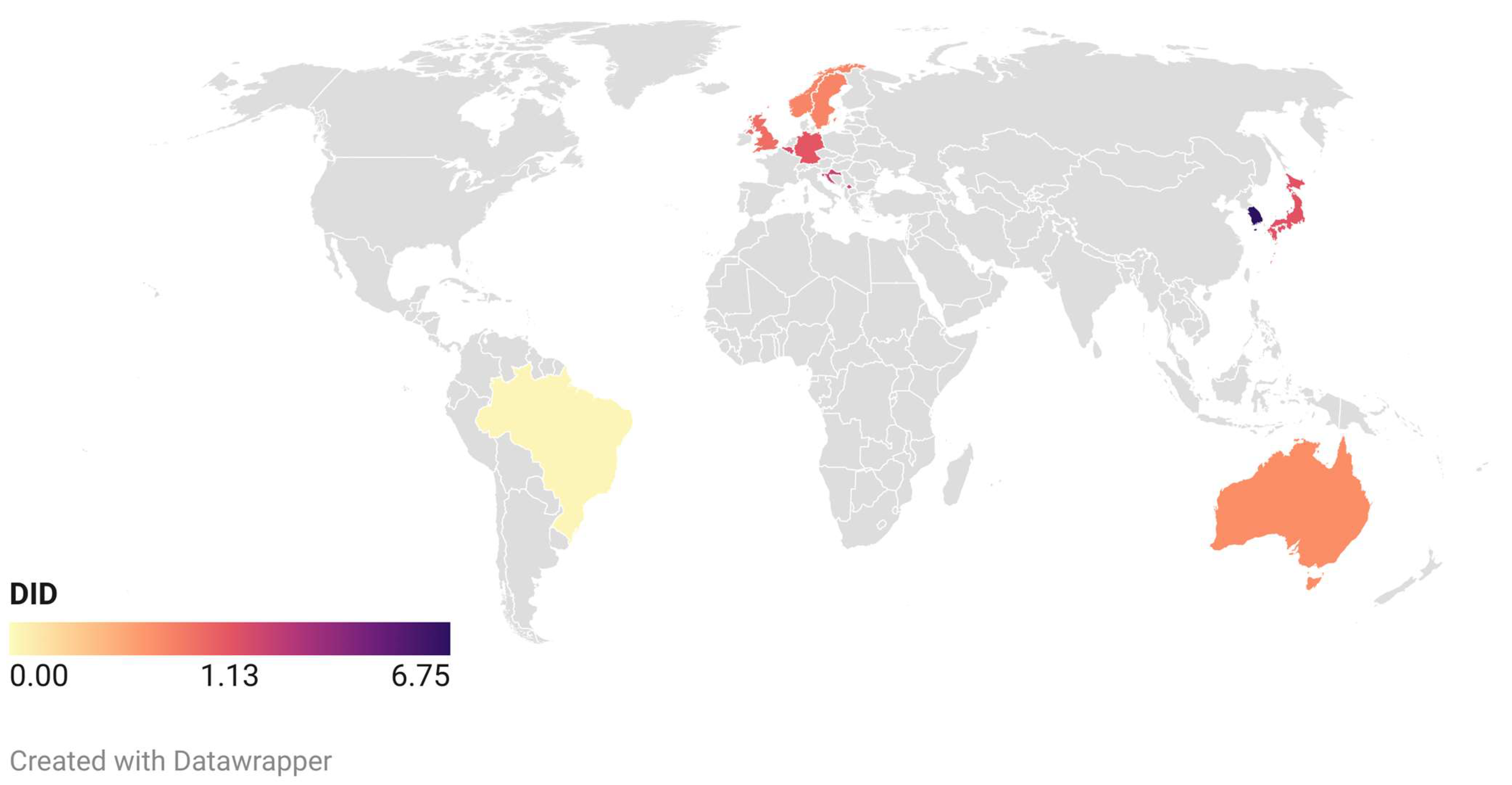

2.4. Mapping Antibiotic Prescription in Dentistry around the World

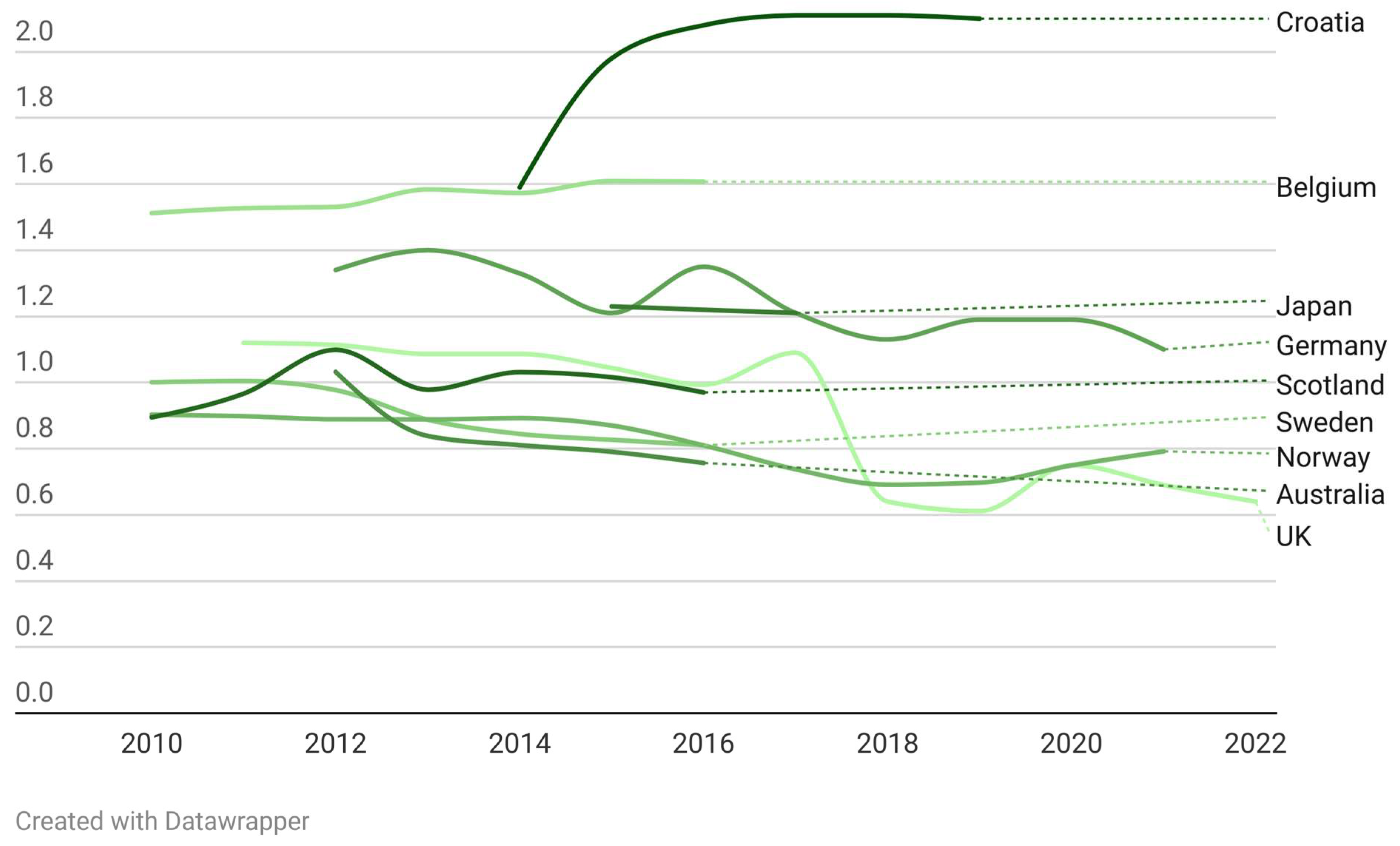

2.5. Antibiotic Prescription Trends by Dentists before, during, and after COVID-19 Pandemic

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Search Strategy

4.2. Study Selection

4.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria: studies reporting DDDs for antibiotics prescribed by dentists/dental specialists or information provided to calculate DDDs.

- Exclusion Criteria: Survey or questionnaire studies, studies reported solely physicians’ data, single dentist reports, studies based on interns or students’ prescriptions, studies with sample size less than 1000 prescription, and review articles. Review articles were used to manually search their references. These references passed through title and abstract screening stages.

4.4. Data Extraction

Data Management

- o

- Name of the first author;

- o

- Title;

- o

- Publication year;

- o

- Time window of study;

- o

- Database to collect data;

- o

- Details of the studied population;

- o

- Care provider (dentists/specialists);

- o

- Most prescribed antibiotics;

- o

- DDDs per 1000 habitants per day (DID) for each year in the time window of the study;

- o

- Type of antibiotic prescription (therapeutic/prophylactic);

- o

- Number of studied prescriptions.

4.5. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) Report 2022; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2022.

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kraker, M.E.; Stewardson, A.J.; Harbarth, S. Will 10 Million People Die a Year due to Antimicrobial Resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizterland, 2023.

- Petrac, L.; Gvozdanovic, K.; Perkovic, V.; Petek Zugaj, N.; Ljubicic, N. Antibiotics Prescribing Pattern and Quality of Prescribing in Croatian Dental Practices-5-Year National Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, A.; Stapf, M.; Brands, R.C.; Kübler, A.C.; Lâm, T.T.; Vollmer, A.; Gubik, S.; Scherf-Clavel, O.; Hartmann, S. Investigation of clindamycin concentrations in human plasma and jawbone tissue in patients with osteonecrosis of the jaw: A prospective trial. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. Off. Publ. Eur. Assoc. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 52, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.; Williams, D.; Pulcini, C.; Sanderson, S.; Calfon, P.; Verma, M. The Essential Role of the Dental Team in Reducing Antibiotic Resistance; FDI World Dental Federation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, H.; Schiegnitz, E.; Halling, F. Facts and trends in dental antibiotic and analgesic prescriptions in Germany, 2012–2021. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousi, F.; Al Haroni, M.; Lie, S.A.; Lund, B. Antibiotic prescriptions among dentists across Norway and the impact of COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, M.R.; Nagrath, D.; Mishra, V.K.; Harris, R.; Saeed, S.S.; Selvaraj, S.; Mehta, A.; Farooqui, H.H. Antibiotic prescriptions for oral diseases in India: Evidence from national prescription data. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends in Dental Antibiotic Prescribing in Wisconsin 2018–2021; Wisconsin Department of Health Services Healthcare-Associated Infections Prevention Program: Madison, WI, USA, 2023.

- Kusumoto, J.; Uda, A.; Kimura, T.; Furudoi, S.; Yoshii, R.; Matsumura, M.; Miyara, T.; Akashi, M. Effect of educational intervention on the appropriate use of oral antimicrobials in oral and maxillofacial surgery: A retrospective secondary data analysis. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A.A.H.; Alzahrani, M.S.A.; Aldannish, B.H.; Alghamdi, H.S.; Albanghali, M.A.; Almalki, S.S.R. Inappropriate Dental Antibiotic Prescriptions: Potential Driver of the Antimicrobial Resistance in Albaha Region, Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, M.J.; Feng, Q.; Warren, K.; Lockhart, P.B.; Thornhill, M.H.; Munshi, K.D.; Henderson, R.R.; Hsueh, K.; Fraser, V.J. Assessment of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among a large cohort of general dentists in the United States. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Asmar Ramli, G.; Mokhbat, J.E.; Cochelard, D.; Lemdani, M.; Haddadi, A.; Ayoub, F. Appropriateness of Therapeutic Antibiotic Prescriptions by Lebanese Dentists in the Management of Acute Endodontic Abscesses. Cureus 2020, 12, e7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Total Consumption of Antibiotics Expressed as Defined Daily Doses (DDD) per 1000 Inhabitants per Day. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/5766 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.S.; Cruz, A.; Ruas, C.M.; Pereira Júnior, E.A.; Mattos, F.F.; Klevens, R.M.; Abreu, M. What we know about antibiotics prescribed by dentists in a Brazilian southeastern state. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl, G.; Kieble, M.; Nagaba, J.; Schulz, M. Assessment of the Prescriptions of Systemic Antibiotics in Primary Dental Care in Germany from 2017 to 2021: A Longitudinal Drug Utilization Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šutej, I.; Lepur, D.; Božić, D.; Pernarić, K. Medication Prescribing Practices in Croatian Dental Offices and Their Contribution to National Consumption. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.Y.; Lee, K.H. Changes in Antibiotic Prescription After Tooth Extraction: A Population-Based Study from 2002 to 2018. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Al-Mahdi, R.; Malcolm, W.; Palmer, N.; Dahlen, G.; Al-Haroni, M. Comparison of antimicrobial prescribing for dental and oral infections in England and Scotland with Norway and Sweden and their relative contribution to national consumption 2010–2016. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, A.; Ishikane, M.; Kusama, Y.; Tanaka, C.; Ono, S.; Tsuzuki, S.; Muraki, Y.; Yamasaki, D.; Tanabe, M.; Ohmagari, N. The first national survey of antimicrobial use among dentists in Japan from 2015 to 2017 based on the national database of health insurance claims and specific health checkups of Japan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, T.; Vandael, E.; Leroy, R.; Mertens, K.; Catry, B. Antimicrobial prescribing by Belgian dentists in ambulatory care, from 2010 to 2016. Int. Dent. J. 2019, 69, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, L.; Stewart, K.; Marino, R.J.; McCullough, M.J. Part 1. Current prescribing trends of antibiotics by dentists in Australia from 2013 to 2016. Aust. Dent. J. 2018, 63, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliti, N.; Krasniqi, S.; Begzati, A.; Gllareva, B.; Krasniqi, L.; Shabani, N.; Mehmeti, B.; Haliti, F. Antibiotic prescription patterns in primary dental health care in Kosovo. Fam. Med. Prim. Care Rev. 2017, 19, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, P.J.; Saladine, C.; Zhang, K.; Hollingworth, S.A. Prescribing patterns of dental practitioners in Australia from 2001 to 2012. Antimicrobials. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Health Security Agency. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2022 to 2023; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tolksdorf, K.; Freytag, A.; Bleidorn, J.; Markwart, R. Antibiotic use by dentists in Germany: A review of prescriptions, pathogens, antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic stewardship strategies. Community Dent. Health 2022, 39, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2021 to 2022; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2018; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2018–2019; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2019–2020; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UK Health Security Agency. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2020 to 2021; UK Health Security Agency: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Hua, F.; Bian, Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and Future Challenges for Dental and Oral Medicine. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, M.; Teoh, L.; Hopcraft, M. Trends in Dental Medication Prescribing in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2021, 6, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.M.; Goulao, B.; Clarkson, J.; Young, L.; Ramsay, C.R. ‘You had to do something’: Prescribing antibiotics in Scotland during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and remobilisation. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Wordley, V.; Thompson, W. How did COVID-19 impact on dental antibiotic prescribing across England? Br. Dent. J. 2020, 229, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, A.; Vazquez-Cancela, O.; Pineiro-Lamas, M.; Figueiras, A.; Zapata-Cachafeiro, M. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Antibiotic Prescribing by Dentists in Galicia, Spain: A Quasi-Experimental Approach. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, M.H.; Dayer, M.J.; Durkin, M.J.; Lockhart, P.B.; Baddour, L.M. Oral antibiotic prescribing by NHS dentists in England 2010-2017. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagde, H.; Dhopte, A. Comparative Analysis of Antibiotic Prescribing Patterns for Dental Infections: A Retrospective Study in a Dental Clinic. Int. J. Pharm. Qual. Assur. 2023, 14, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Yan, C.H.; Hubbard, C.; Calip, G.S.; Sharp, L.K.; Evans, C.T.; Rowan, S.; McGregor, J.C.; Gross, A.E.; Hershow, R.C.; et al. Changes in antibiotic prescribing by dentists in the United States, 2012–2019. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2023, 44, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppen, L.; Suda, K.J.; Rowan, S.; McGregor, J.; Evans, C.T. Dentists’ prescribing of antibiotics and opioids to Medicare Part D beneficiaries: Medications of high impact to public health. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. (1939) 2018, 149, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnarain, P.; Singh, S. Oral antibiotic prescription patterns for dental conditions at two public sector hospitals in Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2022, 77, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncuoglu, C.Z.; Aydin, M.; Kirmizi, N.I.; Aydin, V.; Aksoy, M.; Isli, F.; Akici, A. Rational use of medicine in dentistry: Do dentists prescribe antibiotics in appropriate indications? Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 73, 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, K.J.; Calip, G.S.; Zhou, J.; Rowan, S.; Gross, A.E.; Hershow, R.C.; Perez, R.I.; McGregor, J.C.; Evans, C.T. Assessment of the Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescriptions for Infection Prophylaxis Before Dental Procedures, 2011 to 2015. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e193909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, K.J.; Fitzpatrick, M.A.; Gibson, G.; Jurasic, M.M.; Poggensee, L.; Echevarria, K.; Hubbard, C.C.; McGregor, J.C.; Evans, C.T. Antibiotic prophylaxis prescriptions prior to dental visits in the Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA), 2015–2019. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Plan Estratégico 2022–2024 del Plan Nacional Frente a la Resistencia a los Antibióticos (PRAN); Plan Nacional Resistencia Antibióticos: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, L.; Islami, H.; Sutej, I. Administration of Systemic Antibiotics for Dental Treatment in Kosovo Major Dental Clinics: A National Survey. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.; Teoh, L.; Hubbard, C.C.; Marra, F.; Patrick, D.M.; Mamun, A.; Campbell, A.; Suda, K.J. Patterns of dental antibiotic prescribing in 2017: Australia, England, United States, and British Columbia (Canada). Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2022, 43, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, M.; von den Baumen, T.R.; Chu, C.; Gomes, T.; Schwartz, K.L.; Tadrous, M. Interprovincial variation in antibiotic use in Canada, 2019: A retrospective cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open 2022, 10, E262–E268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmsmann, T.; Himmel, W. Discrepancies between prescribed and defined daily doses: A matter of patients or drug classes? Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Definition and General Considerations; Norwegian Institute of Public Health: Trondheim, Norway, 2024.

- Defined Daily Dose (DDD); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Team, T.E. EndNote; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Country | Time Frame | Database | P/T | D/S | Most Prescribed Antibiotic | Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petrac, L et al. [5] | Croatia | 2015–2019 | All public health dental offices e-Prescriptions from the Croatian Health Insurance Fund (CHIF). | T | D | Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (75.2%), amoxicillin (13.8%), clindamycin (4.8%), metronidazole (2.8%) cephalexin (1.4%). | “During observed period, DID increased 6% and 5% in urban and rural areas, respectively”. |

| Albrecht, H et al. [8] | Germany | 2012–2021 | Research Institute for Local Health Care Systems (WIdO, Berlin). The report includes all medical and dental prescriptions for members of statutory health insurance (SHI). SHI covers 88% of population. | T | D | The group of penicillin derivatives, consisting of oral penicillin, aminopenicillins, and amoxicillin combinations, accounts for 67.1% of all antibiotics prescribed in 2021. Amoxicillin was the first choice of aminopenicillins. | “An overall decline of 17.9% in the rate of DID in members of the statutory health insurance was observed”. |

| Tousi, F et al. [9] | Norway | 2016–2021 | Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Norwegian Prescriptions Database (NorPD). Drugs that are purchased without prescriptions over the counter or supplied to hospitals and nursing homes are not included. | T | D/S | Phenoxymethylpenicillin (68.7%), amoxicillin(10.5%), clindamycin (8.0%), metronidazole (8.5%), erythromycin (1.4%). | “It seems that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the increased use of antibiotic prescriptions compared to an otherwise downward trend”. |

| ESPAUR [28] | UK | 2022 | Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) National Action Plan (NAP). | NP | D/S | Amoxicillin (66.7%), metronidazole (28.2%), erythromycin (2.1%). | “Sharp increase observed between 2019 and 2020; DID decreased by 7.4% between 2021 and 2022 but still was more than before pandemic”. |

| Tolksdorf, K et al. [29] | Germany | 2012–2020 | German Federal Dental Association (Bundeszahnärztekammer), German state dental associations (Landeszahnärztekammern); all German dental societies as well as the webpage of the German Working Group of the Scientific Medical Societies (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlich-Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF). | NP | D | Penicillins and aminopenicillins (70% of all prescriptions), clindamycin (26%). | “In contrast to other outpatient physicians, the volume of antibiotics prescribed by dentists in Germany did not decrease over the last decade. Between 2012 and 2015, there was a shift from clindamycin towards amoxicillin”. |

| Santos, JS et al. [18] | Brazil | 2017 | Integrated Pharmaceutical Services Management System (SIGAF, in Portuguese)/Secondary data from SIGAF/SES-MG) from the second most populous state in the Brazil. | T | D | Amoxicillin (88.46%), azithromycin (8.89%), amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (3.04%), cephalexin (2.24%). | |

| Gradl, G et al. [19] | Germany | 2017–2021 | Data from German Institute for Drug Use Evaluation (DAPI) contain anonymous dispensing data from community pharmacies, claimed to the statutory health insurance (SHI) funds. SHI covers 88% of the population. | NP | D | Amoxicillin (0.63 DID, 50% share), clindamycin (0.29 DID, 24% share), amoxicillin and beta-lactamase inhibitor (0.16 DID, 13% share), phenoxymethylpenicillin (0.08 DID, 6% share), doxycycline (0.03 DID, 2% share), cefuroxime (0.02 DID, 2% share), metronidazole (0.01 DID, 1% share). | “Before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, DID of all antibiotics showed typical seasonal fluctuations with high values during winter months and low values during summer months. In the period from January 2017 to March 2020, values ranged between 8.92 and 17.93 DID (mean 11.99 ± 2.27). From April 2020 to December 2021, they ranged between 6.32 and 10.86 DID (mean 7.84 ± 1.16)”. |

| Sutej, I et al. [20] | Croatia | 2014–2018 | Croatian Health Insurance Fund covering 87.5% of population. The data did not include private prescriptions or medicines dispensed to hospitalized patients. | NP | D | Amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (amoxiclav) (56%), amoxicillin (13.9%), clindamycin (12.5%), metronidazole (10%). | “An increase in the overall prescription rate for all medications prescribed by dentists especially in amoxicillin with clavulanic acid”. |

| Choi, YY et al. [21] | South Korea | 2002–2018 | National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC) of Korea established the National Health Insurance Data Sharing Service (NHISS) database covering more than 99% of population. Ten percent of patients with extraction treatments was selected. | NP | D | Broad-spectrum antibiotics (47.8%). | “The rate of prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics after tooth extraction was 44.1% in 2002 and 60.4% in 2018 (p < 0.001), and it was significantly higher in dental hospitals than in dental clinics (67.4% and 45.9%, respectively, p < 0.001)”. |

| Smith, A et al. [22] | UK | 2011–2016 | NHS Business Service Authority for England and from the prescribing Information System. | NP | D | Amoxicillin, metronidazole, erythromycin, and phenoxymethyl penicillin (ordered from highest to lowest). | “The highest annual rate of antibiotic prescribing per dentist was in England in 2011 (n = 171); by 2016, this had declined to 133 antibiotic prescriptions per year. This represented the highest number of prescriptions per dentist from all 4 countries. In Scotland, the prescription rate per dentist peaked in 2012 (n = 119) and had declined to 87 per annum by 2016. Norway had the lowest rates of prescriptions per dentist (peaking at 31 in 2014) with a decline in prescriptions to 26 per year by 2016. Swedish prescribing levels were highest in 2010 (n = 36) and declined to 28 per annum by 2016”. |

| Scotland | 2010–2016 | NHS National Services Scotland. | |||||

| Sweden | Public Health Agency of Sweden. | Phenoxymethyl penicillin, amoxicillin, clindamycin, and then metronidazole (ordered from highest to lowest). | |||||

| Norway | Norwegian prescription database (NorPD). | ||||||

| Ono, A et al. [23] | Japan | 2015–2017 | Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB) covering all citizens and long-term residents. | NP | D | Cephalosporins accounted for the majority of antimicrobials with DID values (proportion of total antimicrobials) of 0.81 (65.6%) in 2015, 0.80 (65.2%) in 2016, and 0.77 (63.7%) in 2017. | “Over the study period, the DID values of penicillin gradually increased while those of cephalosporins slowly decreased”. |

| Struyf, T et al. [24] | Belgium | 2010–2016 | Reimbursement data from INAMI-RIZIV, Farmanet covering 98.6% of population. Data of hospitalized patients are not included. | NP | D/S | Broad- or extended-spectrum penicillins such as amoxicillin, with and without an enzyme inhibitor. These two antibiotics accounted for 87.7% of all DID of J01 in 2016. | “After an initial increase from 852 DDD/prescriber in 2010 to 893 DDD/prescriber in 2013, the mean rate of DDD/prescriber declined to 869 in 2016”. |

| Teoh, L et al. [25] | Australia | 2013–2016 | Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) covering non-concessional and concessional beneficiaries. | NP | D/S | Amoxicillin (64.3%), metronidazole (13.9%), the broad-spectrum combination product amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (10.4%), clindamycin (5%) in 2016. | “The total number of prescriptions of systemic antibiotics decreased from 2013 to 2016 by 7.3% from 892,483 to 827,020, respectively”. |

| Haliti N et al. [26] | Kosovo | 2015 | Twelve primary dental care centers from six administrative regions including Main Family Medicine Center (MFMC) and Family Medicine Center (FMC). One of every fifteen records was chosen for analysis. | NP | D | Co-amoxiclav (J01CR02), with a 1.16 DID, amoxicillin (J01CA04), with a 0.78 DID. | |

| Ford, PJ et al. [27] | Australia | 2001–2012 | Australian Government’s subsidized medicine formulary, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule (PBS), covering data of concessional beneficiaries who receive social security benefits. | NP | D | Amoxicillin (66.3%), metronidazole (13.6%), amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid (7.1%), clindamycin (6.1%) in 2012. | “This study shows that dispensed use of antibiotics by dental practitioners in Australia has increased over the studied period”. |

| Country | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| England [28,30,31,32,33,34] | 1.086 | 1.086 | 1.044 | 0.993 | 1.09 | 0.640 | 0.611 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.64 | |||

| England [22] | 1.12 | 1.1135 | 1.0814 | 1.0741 | 1.0397 | 0.986 | |||||||

| Brazil [18] | 0.0504 | ||||||||||||

| Germany [8] | 1.34 | 1.4 | 1.33 | 1.21 | 1.35 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.1 | |||

| Germany [29] | 1.069 | 1.145 | 1.106 | 0.997 | 1.1168 | 1.022 | 0.9596 | 0.978 | 0.9877 | ||||

| Germany [19] | 1.20 | 1.185 | 1.193 | 1.169 | 1.245 | ||||||||

| Croatia [5] | 1.98 | 2.08 | 2.11 | 2.11 | 2.1 | ||||||||

| Croatia [20] | 1.59 | 1.67 | 1.73 | 1.76 | 1.78 | ||||||||

| Norway [9] | 0.7796 | 0.7374 | 0.691 | 0.697 | 0.7494 | 0.7918 | |||||||

| Norway [22] | 0.903 | 0.8979 | 0.8887 | 0.8882 | 0.8925 | 0.8699 | 0.81 | ||||||

| South Korea [21] | 6.09 | 6.25 | 6.42 | 6.53 | 6.59 | 6.69 | 6.75 | 6.85 | 6.97 | ||||

| Scotland [22] | 0.8945 | 0.9664 | 1.0331 | 0.9782 | 1.0311 | 1.0158 | 0.97 | ||||||

| Sweden [22] | 1.0009 | 1.0044 | 0.9772 | 0.8875 | 0.8446 | 0.8267 | 0.81 | ||||||

| Japan [23] | 1.23 | 1.22 | 1.21 | ||||||||||

| Belgium [24] | 1.512 | 1.527 | 1.531 | 1.584 | 1.573 | 1.609 | 1.607 | ||||||

| Australia [25] | 0.8383 | 0.8105 | 0.7905 | 0.7567 | |||||||||

| Australia [27] | 1.032 | ||||||||||||

| Kosovo [26] | 2.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soleymani, F.; Pérez-Albacete Martínez, C.; Makiabadi, M.; Maté Sánchez de Val, J.E. Mapping Worldwide Antibiotic Use in Dental Practices: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090859

Soleymani F, Pérez-Albacete Martínez C, Makiabadi M, Maté Sánchez de Val JE. Mapping Worldwide Antibiotic Use in Dental Practices: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(9):859. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090859

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoleymani, Fatemeh, Carlos Pérez-Albacete Martínez, Mehrdad Makiabadi, and José Eduardo Maté Sánchez de Val. 2024. "Mapping Worldwide Antibiotic Use in Dental Practices: A Scoping Review" Antibiotics 13, no. 9: 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090859

APA StyleSoleymani, F., Pérez-Albacete Martínez, C., Makiabadi, M., & Maté Sánchez de Val, J. E. (2024). Mapping Worldwide Antibiotic Use in Dental Practices: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics, 13(9), 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13090859