Plasmid-Mediated Spread of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales: A Three-Year Genome-Based Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

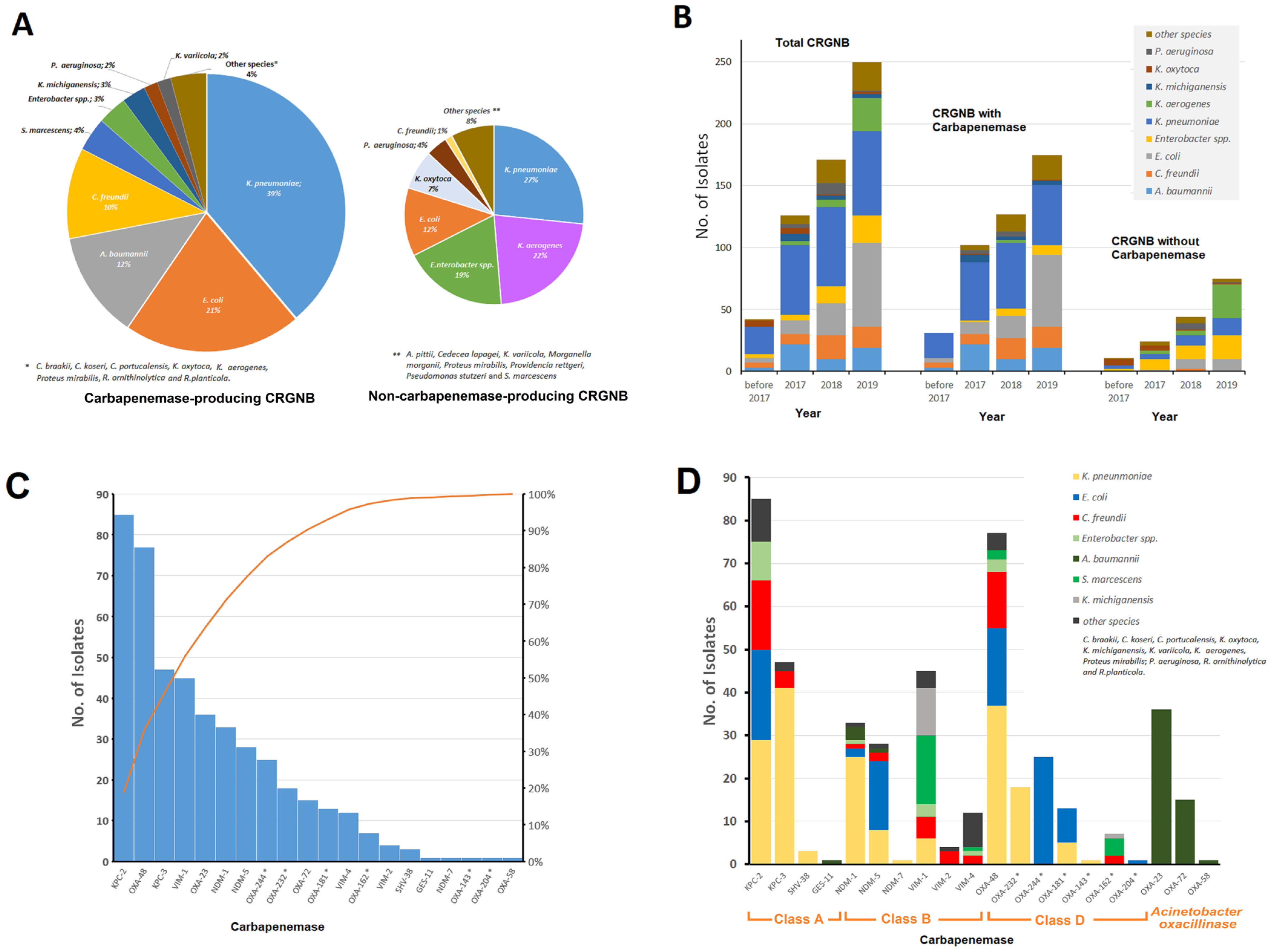

2.1. General Characterization of the CRGNB Population

2.2. Population Structure of Escherichia coli

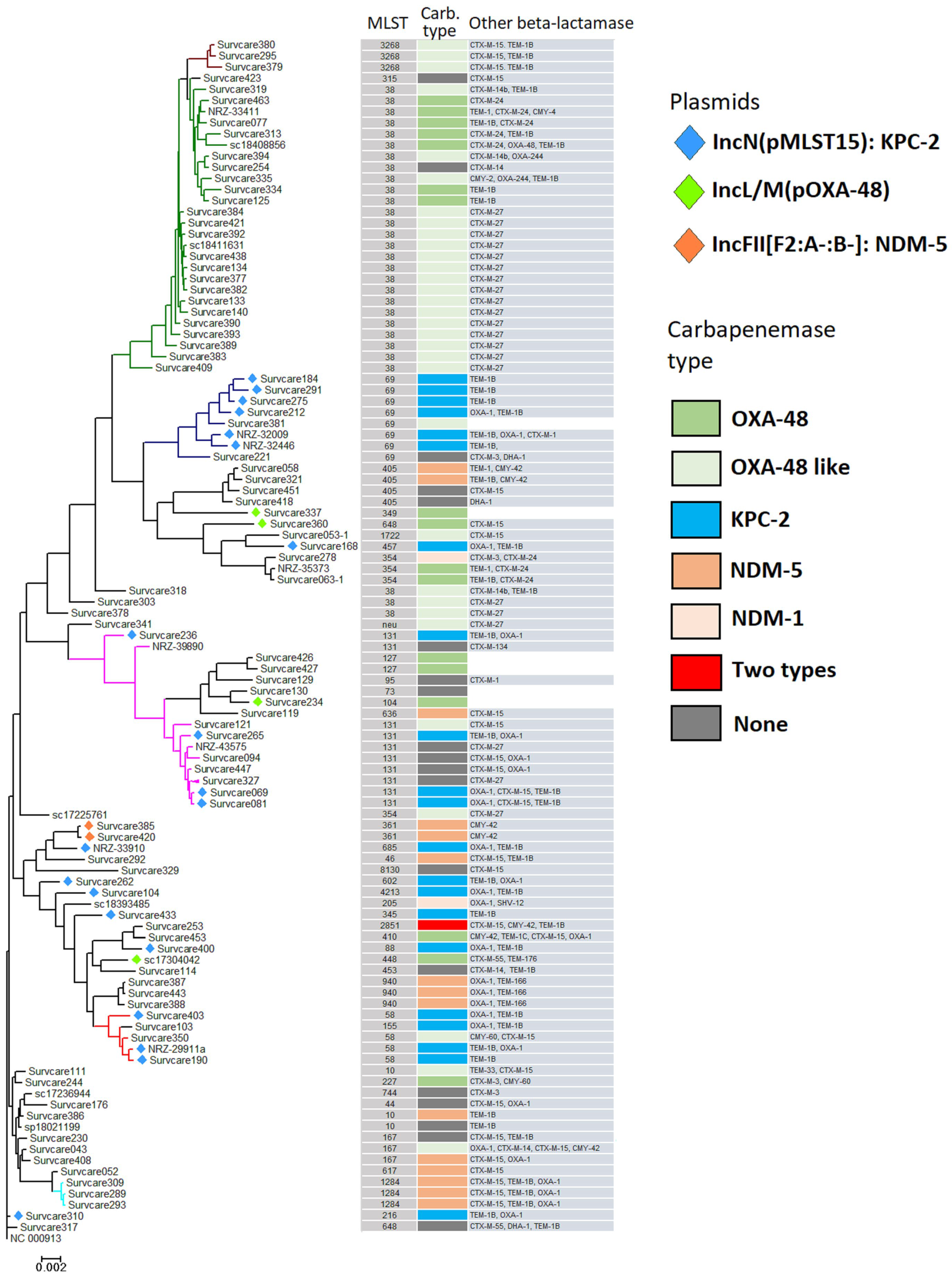

2.3. Population Structure of Klebsiella pneumoniae

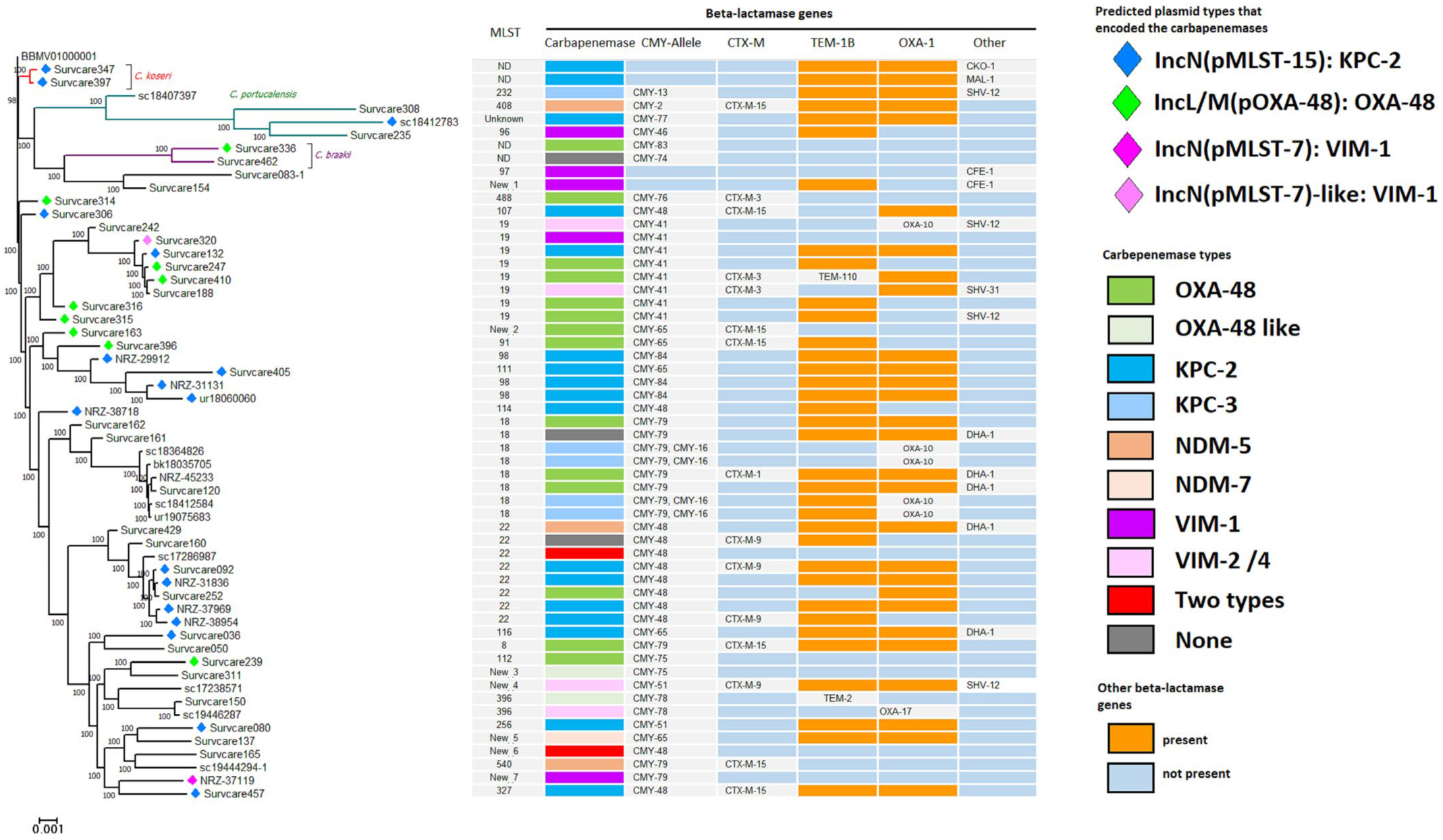

2.4. Population Structure of Citrobacter Species

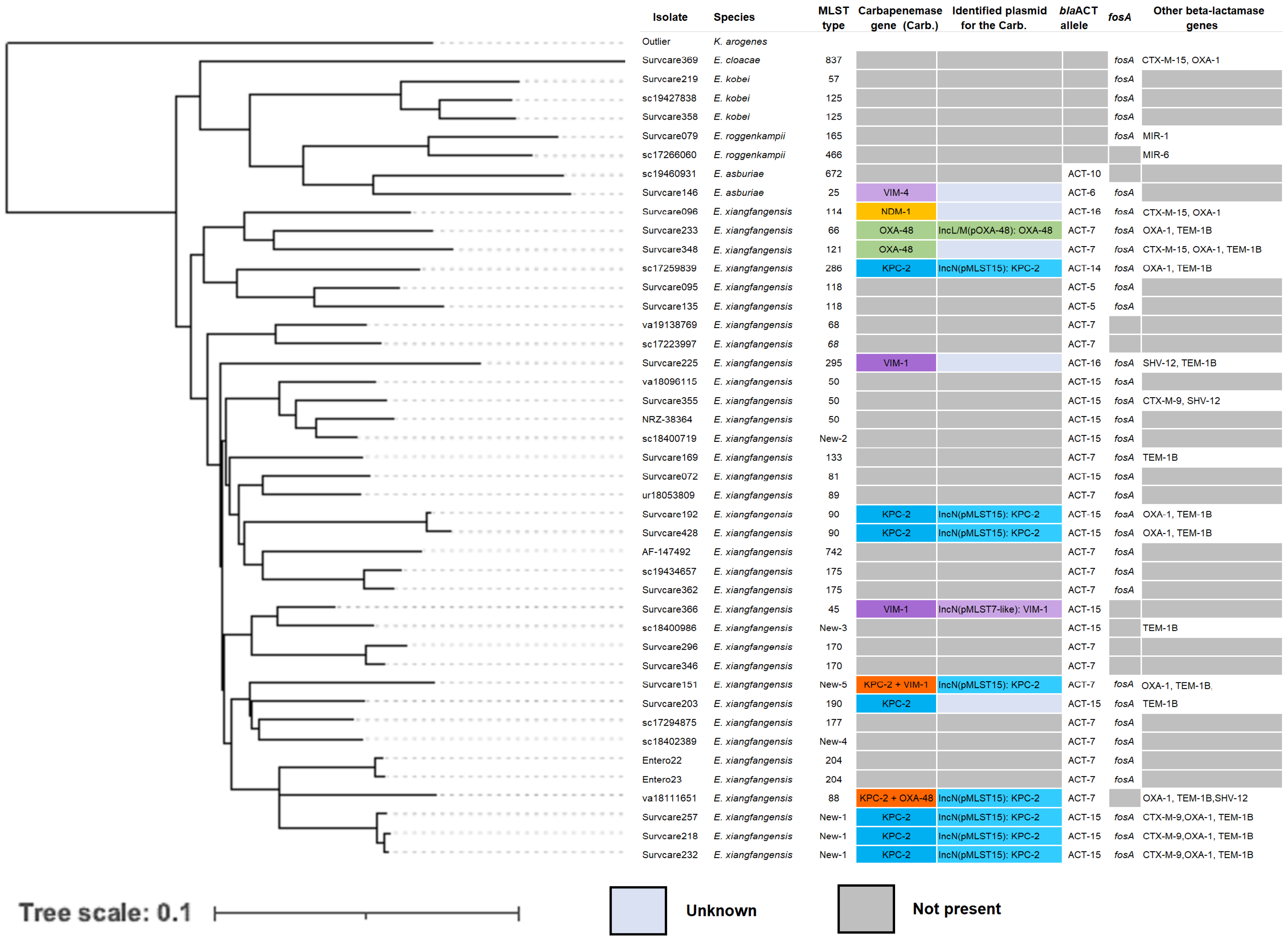

2.5. Population Structure of Enterobacter Species

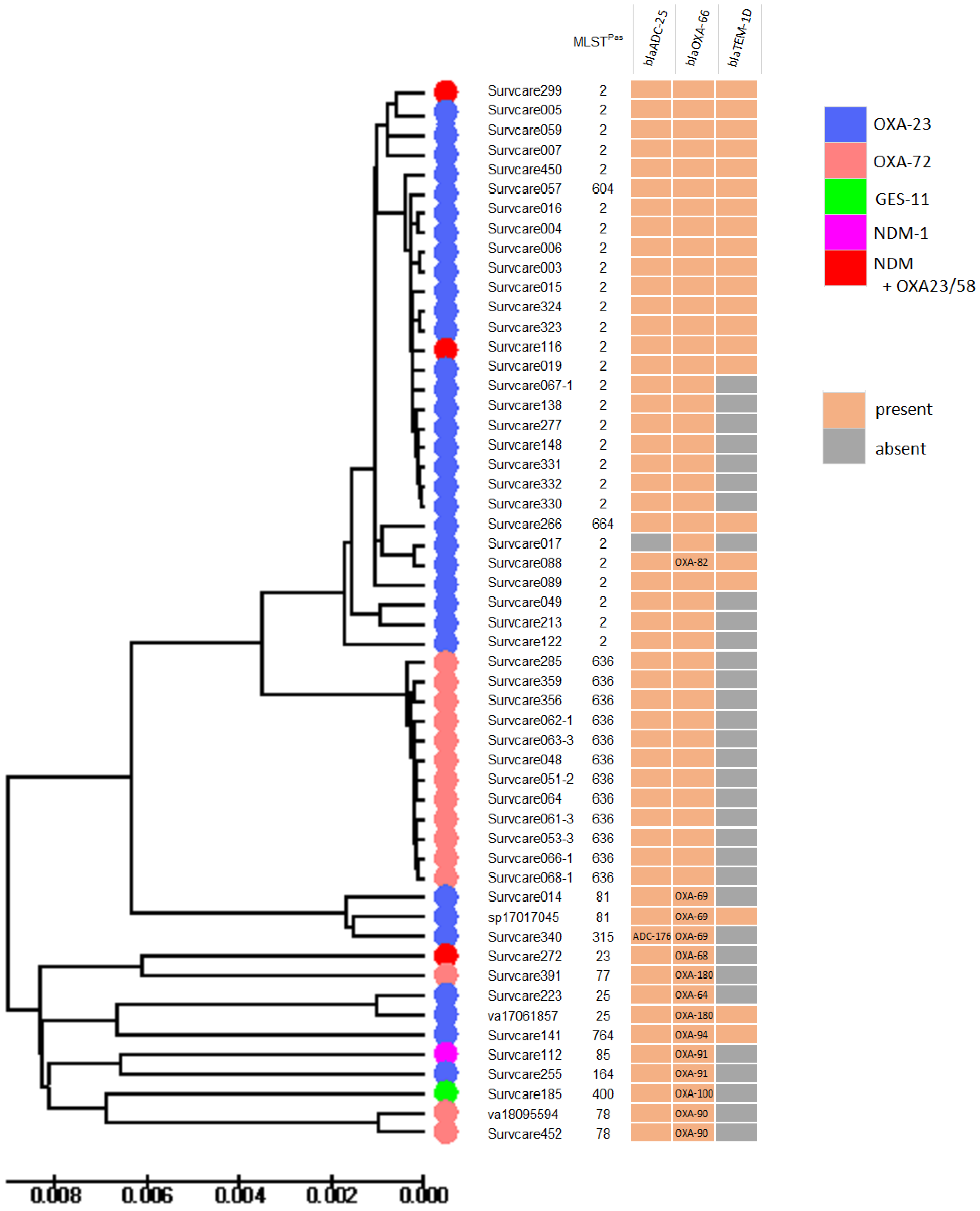

2.6. Population Structure of Acinetobacter baumannii

2.7. Genetic Characteristics of Remaining Species

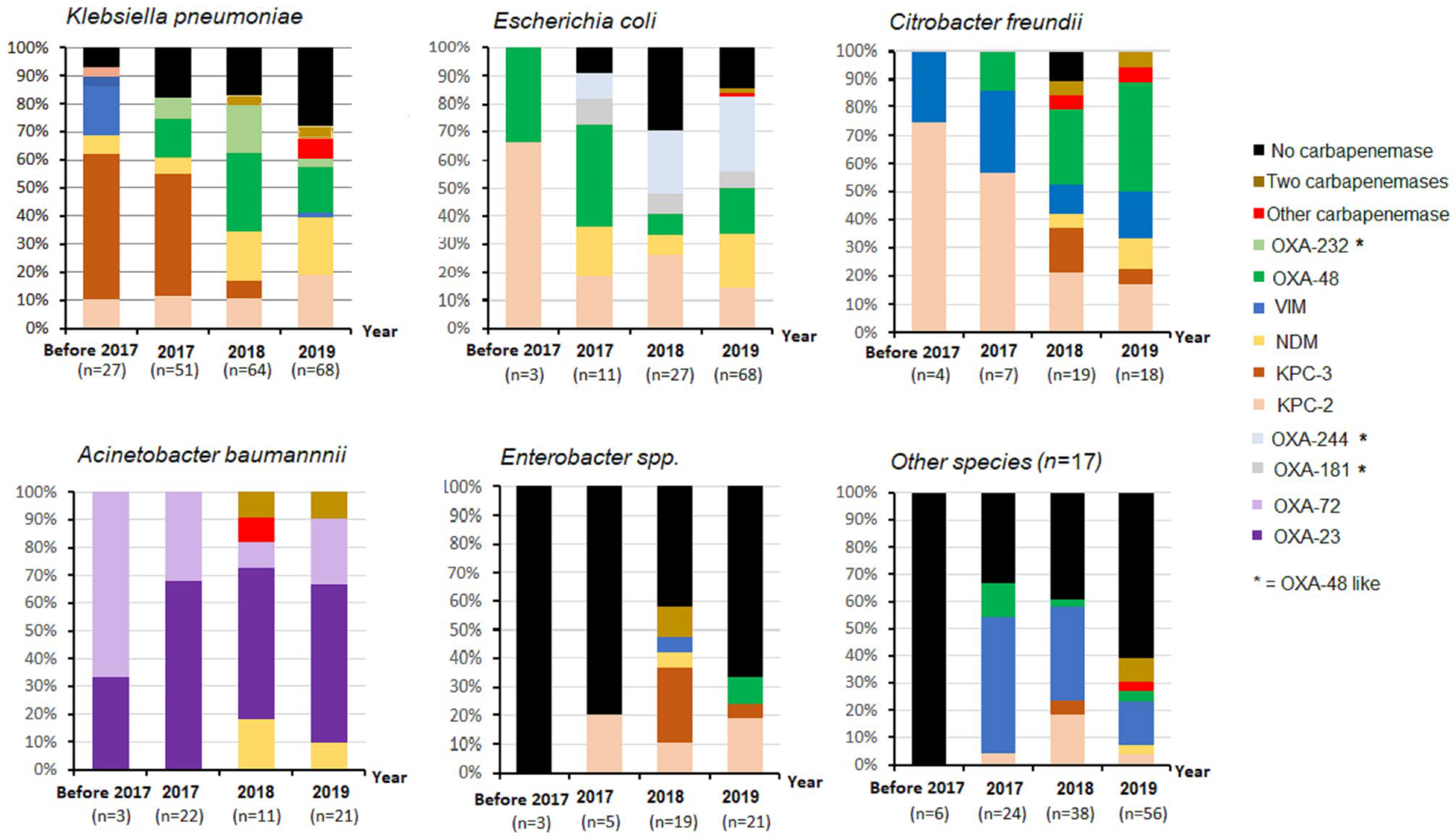

2.8. Distribution of Carbapenemases Detected

2.9. Temporal Changes

2.10. Emergence of Isolates Harboring More than One Carbapenemase

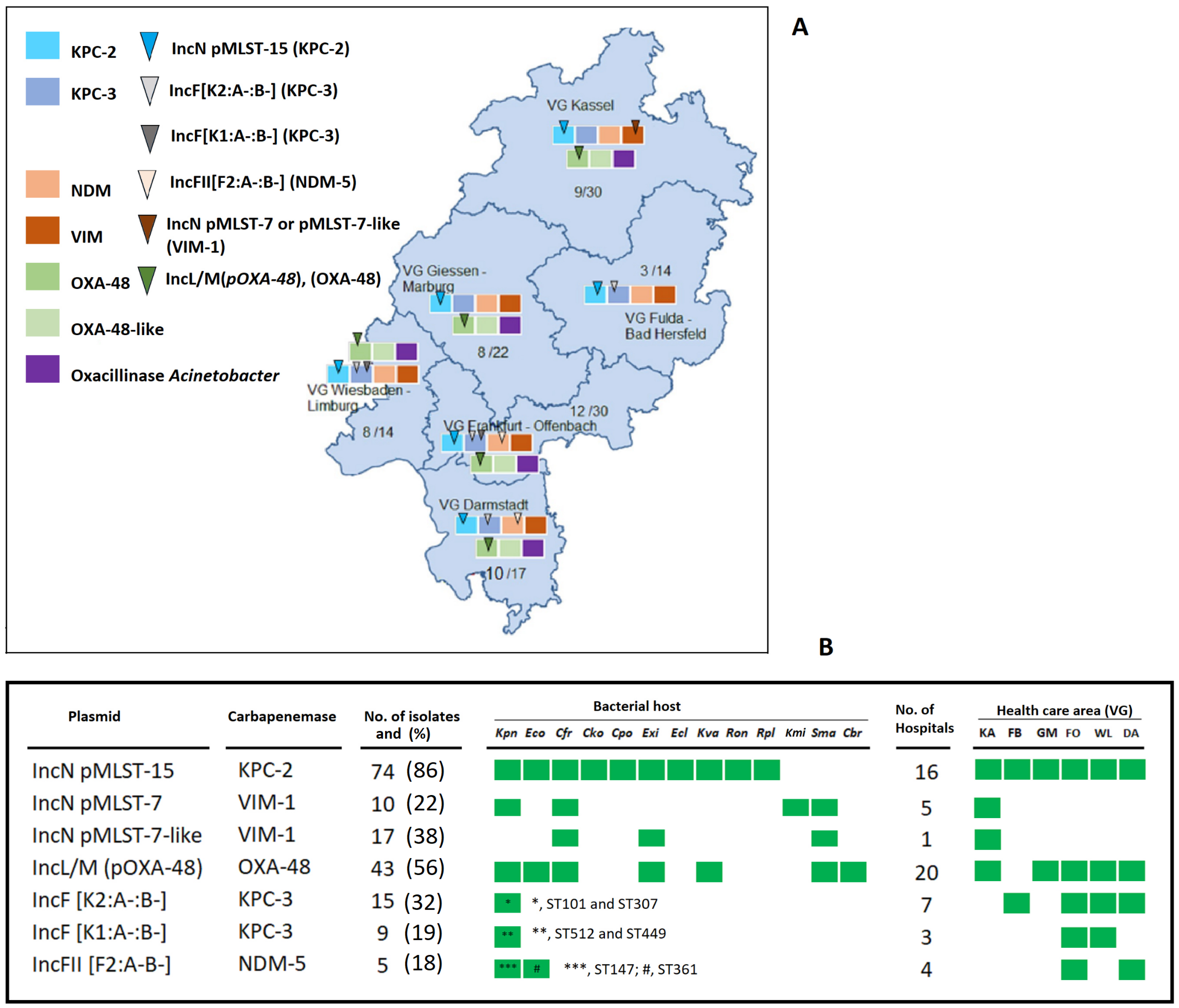

2.11. Characterization of Plasmids in Carbapenemase-Producing CRGNB

2.12. Genetic Characteristics of Non-Carbapenemase-Producing CRGNB

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Setting and Isolate Collection

4.2. Sample Size

- n = required sample size.

- Z = standard normal distribution value at 95% confidence level of a ((Za/2) = 1.96).

- P = proportion of carbapenemase-producing isolates.

- d = margin of error = 5%.

4.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.4. Whole-Genome Sequencing

4.5. Genomic Analysis

4.6. Statistical Tests

4.7. Ethical Approval

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nordmann, P.; Naas, T.; Poirel, L. Global spread of carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brolund, A.; Lagerqvist, N.; Byfors, S.; Struelens, M.J.; Monnet, D.L.; Albiger, B.; Kohlenberg, A. Worsening epidemiological situation of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae in europe, assessment by national experts from 37 countries, July 2018. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1900123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoesser, N.; Phan, H.T.T.; Seale, A.C.; Aiken, Z.; Thomas, S.; Smith, M.; Wyllie, D.; George, R.; Sebra, R.; Mathers, A.J.; et al. Genomic epidemiology of complex, multispecies, plasmid-borne blaKPC carbapenemase in Enterobacterales in the United Kingdom from 2009 to 2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02244-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, B.M.; Montague, B.T.; Anandan, S.; Madabhushi, A.G.; Pragasam, A.K.; Verghese, V.P.; Balaji, V.; Simões, E.A.F. Risk factors and epidemiologic predictors of blood stream infections with new delhi metallo-b-lactamase (NDM-1) producing enterobacteriaceae. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 147, e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, P.D.; Goodman, K.E.; Harris, A.D.; Tekle, T.; Roberts, A.; Taiwo, A.; Simner, P.J. Comparing the outcomes of patients with carbapenemase-producing and non-carbapenemase- producing carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Zwaluw, K.; Witteveen, S.; Wielders, L.; van Santen, M.; Landman, F.; de Haan, A.; Schouls, L.M.; Bosch, T.; Cohen Stuart, J.W.T.; Melles, D.C.; et al. Molecular characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in the Netherlands; results of the 2014–2018 national laboratory surveillance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1412.e7–1412.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordmann, P. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: Overview of a major public health challenge. Med. Mal. Infect. 2014, 44, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halat, D.H.; Moubareck, C.A. The current burden of carbapenemases: Review of significant properties and dissemination among gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantón, R.; Akóva, M.; Carmeli, Y.; Giske, C.G.; Glupczynski, Y.; Gniadkowski, M.; Livermore, D.M.; Miriagou, V.; Naas, T.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozwandowicz, M.; Brouwer, M.S.M.; Fischer, J.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B.; Guerra, B.; Mevius, D.J.; Hordijk, J. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, H.; Glasner, C.; Albiger, B.; Aanensen, D.M.; Tomlinson, C.T.; Andrasević, A.T.; Cantón, R.; Carmeli, Y.; Friedrich, A.W.; Giske, C.G.; et al. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): A prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hernández, I.; Delgado-Valverde, M.; Fernández-Cuenca, F.; López-Cerero, L.; Machuca, J.; Pascual, Á. Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria in Andalusia, Spain, 2014–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2218–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfennigwerth, N. Bericht des Nationalen Referenzzentrums für gramnegative Krankenhauserreger Zeitraum 1 Januar 2019 bis 31 Dezember 2019. RKI Epidemiol. Bull. 2020, 29, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfenningwerth, N. Bericht des Nationalen Referenzzentrums für gramnegative Krankenhauserreger Zeitraum 1 Januar 2017–31 Dezember 2017. Epidemiol. Bull. 2018, 28, 263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Pfenningwerth, N. Bericht des Nationalen Referenzzentrums für gramnegative Krankenhauserreger, 2018. Epidemiol. Bull. 2019, 31, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Pfenningwerth, N. Bericht des Nationalen Referenzzentrums für gramnegative Krankenhauserreger, 2019. Epidemiol. Bull. 2020, 26, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hauri, A.; Kaase, M.; Hunfeld, K.; Heinmüller, P.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Wichelhaus, T.; Fitzenberger, J.; Wirtz, A. Results on the mandatory notification of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, Hesse, Germany, January 2012–April 2013. GMS Infect. Dis. 2014, 2, Doc04. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Falgenhauer, L.; Chakraborty, T. New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales Bacteria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koraimann, G. Spread and Persistence of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance Genes: A Ride on the F Plasmid Conjugation Module. EcoSal Plus 2018, 8, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Reuter, S.; Harris, S.R.; Glasner, C.; Feltwell, T.; Argimon, S.; Abudahab, K.; Goater, R.; Giani, T.; Errico, G.; et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.; Kramer, R.; Becker, K.; Bohnert, J.A.; Eckmanns, T.; Hans, J.B.; Hecht, J.; Heidecke, C.D.; Hubner, N.O.; Kramer, A.; et al. Extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST307 outbreak, north-eastern Germany, June to October 2019. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1900734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Wang, W.-Y.; Ko, W.-C.; Hsueh, P.-R. Global epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of Enterobacterales harbouring genes encoding OXA-48-like carbapenemases: Insights from the results of the Antimicrobial Testing Leadership and Surveillance (ATLAS) programme 2018–2021. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, dkae140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuicapuza, D.; Loyola, S.; Velásquez, J.; Fernández, N.; Llanos, C.; Ruiz, J.; Tsukayama, P.; Tamariz, J. Molecular characterization of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in a tertiary hospital in Lima, Peru. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02503-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.S.; Dolan, L.; Jenkins, F.; Crawford, B.; Van Hal, S.J. Active surveillance of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales using genomic sequencing for hospital-based infection control interventions. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2024, 45, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayama, S.; Yahara, K.; Sugawara, Y.; Kawakami, S.; Kondo, K.; Zuo, H.; Kutsuno, S.; Kitamura, N.; Hirabayashi, A.; Kajihara, T.; et al. National genomic surveillance integrating standardized quantitative susceptibility testing clarifies antimicrobial resistance in Enterobacterales. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, L.; Kaase, M.; Pfeifer, Y.; Fuchs, S.; Reuss, A.; von Laer, A.; Sin, M.A.; Korte-Berwanger, M.; Gatermann, S.; Werner, G. Genome-based analysis of Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from German hospital patients, 2008-2014. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2018, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiker, A.; Evans, D.R.; Griffith, M.P.; McElheny, C.L.; Hassan, M.; Clarke, L.G.; Mettus, R.T.; Harrison, L.H.; Doi, Y.; Shields, R.K.; et al. Clinical and genomic epidemiology of carbapenem- nonsusceptible citrobacter spp. At a tertiary health care center over 2 decades. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 20203374908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, D.M.; Ortega, A.; González-Barberá, E.; Lara, N.; Bautista, V.; Gómez-Ruíz, D.; Sáez, D.; Fernández-Romero, S.; Aracil, B.; Pérez-Vázquez, M.; et al. Carbapenem-resistant Citrobacter spp. isolated in Spain from 2013 to 2015 produced a variety of carbapenemases including VIM-1, OXA-48, KPC-2, NDM-1 and VIM-2. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 3283–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, T.; Sadek, M.; Yao, Y.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Stephan, R.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Cross-border emergence of Escherichia coli producing the carbapenemase NDM-5 in Switzerland and Germany. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 59, 20210148799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, L.; Feudi, C.; Fortini, D.; Brisse, S.; Passet, V.; Bonura, C.; Endimiani, A.; Mammina, C.; Ocampo, A.M.; Jimenez, J.N.; et al. Diversity, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance of the KPCproducing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST307 clone. Microb. Genom. 2017, 3, e000110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Hain, T.; Kaase, M.; Gatermann, S.; Exner, M.; Mielke, M.; Hauri, A.; Dragneva, Y.; Bill, R.; et al. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of a Citrobacter freundii Plasmid Carrying KPC-2 in a Unique Genetic Environment. Genome Announc. 2014, 2, e01157-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potron, A.; Poirel, L.; Rondinaud, E.; Nordmann, P. Intercontinental spread of OXA-48 beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae over a 11-year period, 2001 to 2011. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, A.Y.; Seifert, H.; Paterson, D.L. Acinetobacter baumannii: Emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 538–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, M.; Nigro, S.J. Emergence, molecular mechanisms and global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Genom. 2019, 5, e000306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.R.; Acharya, M.; Kakshapati, T.; Leungtongkam, U.; Thummeepak, R.; Sitthisak, S. Co-existence of bla OXA-23 and bla NDM-1 genes of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from Nepal: Antimicrobial resistance and clinical significance. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Reuter, S.; Wille, J.; Xanthopoulou, K.; Stefanik, D.; Grundmann, H.; Higgins, P.G.; Seifert, H. A global view on carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. MBio 2023, 14, e02260-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Ramírez, S. Genomic epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii goes global. MBio 2023, 14, e02520-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Epidemiology and Diagnostics of Carbapenem Resistance in Gram-negative Bacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, S521–S528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, A.; Villagra, N.A.; Undabarrena, A.; Gallardo, N.; Keller, N.; Moraga, M.; Román, J.C.; Mora, G.C.; García, P. Porin alterations present in non-carbapenemaseproducing Enterobacteriaceae with high and intermediate levels of carbapenem resistance in Chile. J. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 61, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, A.; McGlynn, K.; Taffner, S.; Fine, L.; Tesini, B.; Wang, J.; Mostafa, H.; Petry, S.; Perkins, A.; Graman, P.; et al. Next-generation-sequencing-based hospital outbreak investigation yields insight into klebsiella aerogenes population structure and determinants of carbapenem resistance and pathogenicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02577-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Falgenhauer, L.; Rezazadeh, Y.; Falgenhauer, J.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Chakraborty, T.; Hauri, A.M.; Heinmüller, P.; Domann, E.; Ghosh, H.; et al. Predominant transmission of KPC-2 carbapenemase in Germany by a unique IncN plasmid variant harboring a novel non-transposable element (NTE KPC-Y). Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02564-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kommission für Krankenhaushygiene und Infektionsprävention (KRINKO). Ergänzung zur Empfehlung der KRINKO „Hygienemaßnahmen bei Infektionen oder Besiedlung mit multiresistenten Gram- negativen Stäbchen“ (2012) im Zusammenhang mit der von EUCAST neu definierten Kategorie “I” bei der Antibiotika-Resistenzbestimmung. Konsequenzen für die Definition von MRGN. Epidemiol. Bull. 2019, 9, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falgenhauer, L.; Nordmann, P.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Yao, Y.; Falgenhauer, J.; Hauri, A.M.; Heinmüller, P.; Chakraborty, T. Cross-border emergence of clonal lineages of ST38 Escherichia coli producing the OXA-48-like carbapenemase OXA-244 in Germany and Switzerland. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darling, A.E.; Mau, B.; Perna, N.T. progressiveMauve: Multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treangen, T.J.; Ondov, B.D.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. The harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Carbapenemase | Species | Year | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 2017 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |||

| KPC | K. pneumoniae | 18 | 28 | 11 | 13 | 70 |

| E. coli | 3 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 21 | |

| C. freundii | 3 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 20 | |

| Enterobacter spp. | – | 1 | 4 | 4 | 9 | |

| C. portucalensis | – | – | 2 | – | 2 | |

| C. koseri | – | – | – | 2 | 2 | |

| K. aerogenes | – | – | 2 | – | 2 | |

| K. variicola | – | 1 | 2 | – | 2 | |

| Raoultella ornithinolytica | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Raoultella planticola | – | – | 2 | – | 2 | |

| All species | 24 | 37 | 38 | 33 | 132 | |

| NDM | K. pneumoniae | 2 | 3 | 13 | 16 | 34 |

| E. coli | – | 2 | 2 | 14 | 18 | |

| C. freundii | – | – | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | – | – | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| C. portucalensis | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| Enterobacter spp. | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| K. oxytoca | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| All species | 2 | 5 | 19 | 36 | 62 | |

| VIM | S. marcescens | – | 3 | 6 | 8 | 17 |

| K. michiganensis | – | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 | |

| C. freundii | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 10 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | – | 3 | 4 | – | 7 | |

| K. pneumoniae | – | 5 | – | 1 | 6 | |

| Enterobacter spp. | – | – | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Proteus mirabilis | – | – | – | 3 | 3 | |

| C. portucalensis | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| All species | 1 | 20 | 18 | 20 | 59 | |

| OXA-48 and | K. pneumoniae | – | 11 | 31 | 19 | 61 |

| OXA-48-like | E. coli | 1 | 6 | 10 | 35 | 52 |

| C. freundii | – | 1 | 6 | 8 | 15 | |

| S. marcescens | – | 2 | – | 4 | 6 | |

| Enterobacter spp. | – | – | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| C. braakii | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| K. michiganensis | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| K. oxytoca | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | |

| K. variicola | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Raoultella ornithinolytica | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | |

| All species | 1 | 21 | 49 | 71 | 142 | |

| OXA-23 | A. baumannii | 1 | 15 | 7 | 13 | 36 |

| OXA-72 | A. baumannii | 2 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 15 |

| OXA-58 | A. baumannii | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| GES-11 | A. baumannii | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| SHV-38 | K. pneumoniae | – | – | – | 3 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, Y.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Falgenhauer, L.; Falgenhauer, J.; Heinmüller, P., on behalf of the SurvCARE Hesse Working Group; Domann, E.; Chakraborty, T. Plasmid-Mediated Spread of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales: A Three-Year Genome-Based Survey. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13080682

Yao Y, Imirzalioglu C, Falgenhauer L, Falgenhauer J, Heinmüller P on behalf of the SurvCARE Hesse Working Group, Domann E, Chakraborty T. Plasmid-Mediated Spread of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales: A Three-Year Genome-Based Survey. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(8):682. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13080682

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Yancheng, Can Imirzalioglu, Linda Falgenhauer, Jane Falgenhauer, Petra Heinmüller on behalf of the SurvCARE Hesse Working Group, Eugen Domann, and Trinad Chakraborty. 2024. "Plasmid-Mediated Spread of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales: A Three-Year Genome-Based Survey" Antibiotics 13, no. 8: 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13080682

APA StyleYao, Y., Imirzalioglu, C., Falgenhauer, L., Falgenhauer, J., Heinmüller, P., on behalf of the SurvCARE Hesse Working Group, Domann, E., & Chakraborty, T. (2024). Plasmid-Mediated Spread of Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales: A Three-Year Genome-Based Survey. Antibiotics, 13(8), 682. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics13080682