Phenotypic and Molecular Traits of Staphylococcus coagulans Associated with Canine Skin Infections in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of S. coagulans and S. schleiferi Isolates

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles and Association with Resistance Determinants

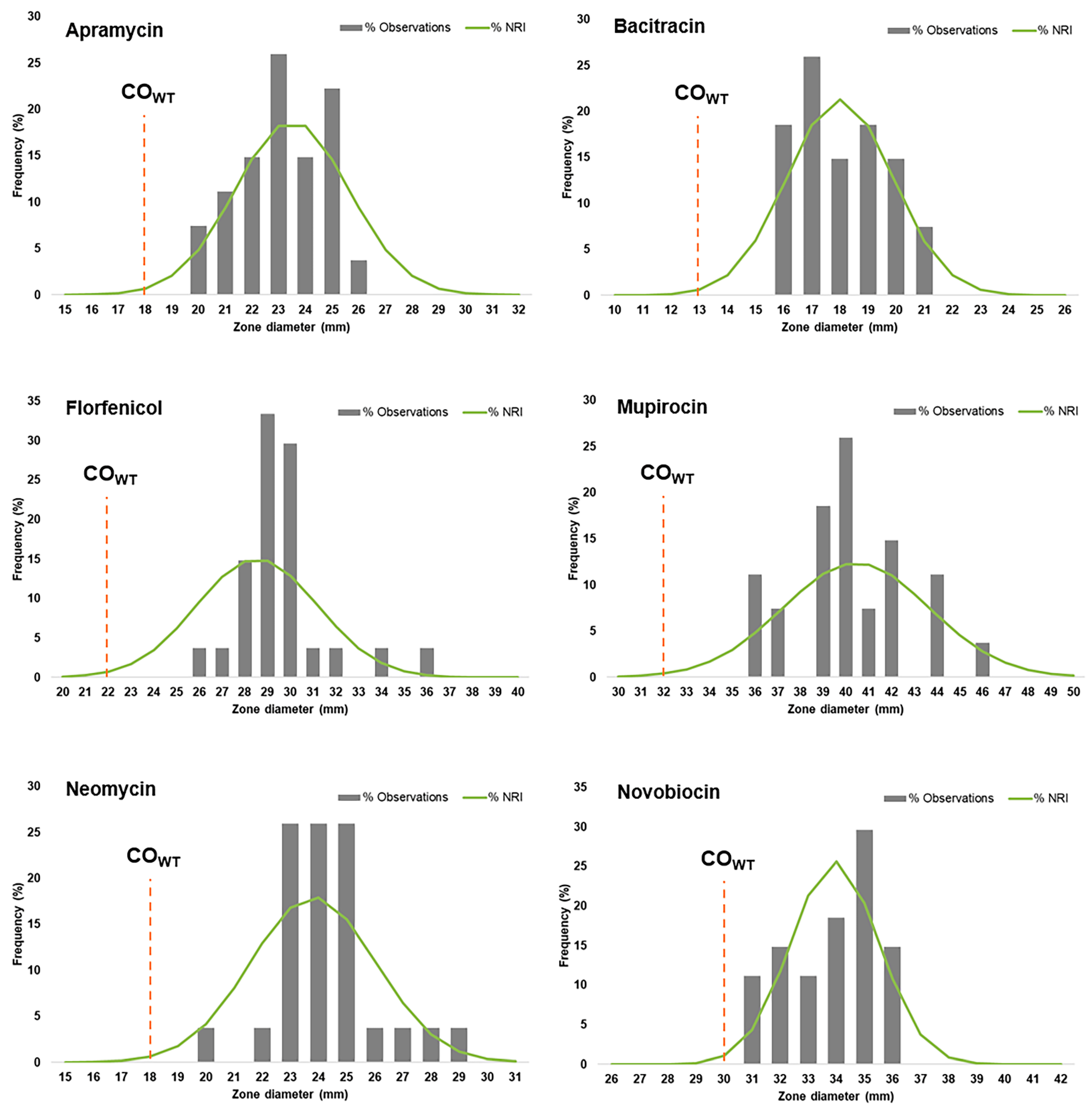

2.3. Distributions of Zone Inhibition Diameters for Antibiotics with No Breakpoints Established

2.4. Plasmid Profiling and Association with Antibiotic Resistance

2.5. Molecular Typing and Association with Antimicrobial Resistance Phenotypes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates

4.2. Total DNA and Plasmid DNA Isolation

4.3. Identification of the Isolates

4.4. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

4.5. Calculation of Cut-Off (COWT) Values

4.6. Screening of Resistance Determinants

4.7. Molecular Typing by SmaI-PFGE

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hillier, A.; Lloyd, D.H.; Weese, J.S.; Blondeau, J.M.; Boothe, D.; Breitschwerdt, E.; Guardabassi, L.; Papich, M.G.; Rankin, S.; Turnidge, J.D.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy of canine superficial bacterial folliculitis (Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases). Vet. Dermatol. 2014, 25, 163-e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, D.O.; Loeffler, A.; Davis, M.F.; Guardabassi, L.; Weese, J.S. Recommendations for approaches to meticillin-resistant staphylococcal infections of small animals: Diagnosis, therapeutic considerations and preventative measures: Clinical Consensus Guidelines of the World Association for Veterinary Dermatology. Vet. Dermatol. 2017, 28, 304-e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, A.; Lloyd, D.H. What has changed in canine pyoderma? A narrative review. Vet. J. 2018, 235, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freney, J.; Brun, Y.; Bes, M.; Meugnier, H.; Grimont, F.; Grimont, P.; Nervi, C.; Fleurette, J. Staphylococcus lugdunensis sp. nov. and Staphylococcus schleiferi sp. nov., two species from human clinical specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1988, 38, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Célard, M.; Vandenesch, F.; Darbas, H.; Grando, J.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Kirkorian, G.; Etienne, J. Pacemaker infection caused by Staphylococcus schleiferi, a member of the human preaxillary flora: Four case reports. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1997, 24, 1014–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, A.; Lelièvre, H.; Pha, D.; Kirkorian, G.; Célard, M.; Chevalier, P.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J.; Touboul, P. Role of the preaxillary flora in pacemaker infections. Circulation 1998, 97, 1791–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igimi, S.; Takahashi, E.; Mitsuoka, T. Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. coagulans subsp. nov., isolated from the external auditory meatus of dogs with external ear otitis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1990, 40, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhaiyan, M.; Wirth, J.S.; Saravanan, V.S. Phylogenomic analyses of the Staphylococcaceae family suggest the reclassification of five species within the genus Staphylococcus as heterotypic synonyms, the promotion of five subspecies to novel species, the taxonomic reassignment of five Staphylococcus species to Mammaliicoccus gen. nov., and the formal assignment of Nosocomiicoccus to the family Staphylococcaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5926–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffeth, G.C.; Morris, D.O.; Abraham, J.L.; Shofer, F.S.; Rankin, S.C. Screening for skin carriage of methicillin-resistant coagulase-positive staphylococci and Staphylococcus schleiferi in dogs with healthy and inflamed skin. Vet. Dermatol. 2008, 19, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, K.; Shimizu, A.; Kawano, J.; Uchida, E.; Haruna, A.; Igimi, S. Isolation and characterization of staphylococci from external auditory meatus of dogs with or without otitis externa with special reference to Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. coagulans isolates. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005, 67, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanselman, B.A.; Kruth, S.; Weese, J.S. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcal colonization in dogs entering a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet. Microbiol. 2008, 126, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, J.L.; Morris, D.O.; Griffeth, G.C.; Shofer, F.S.; Rankin, S.C. Surveillance of healthy cats and cats with inflammatory skin disease for colonization of the skin by methicillin-resistant coagulase-positive staphylococci and Staphylococcus schleiferi ssp. schleiferi. Vet. Dermatol. 2007, 18, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Robb, A.; Paterson, G.K. Isolation and genome sequencing of Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans from Antarctic and North Sea seals. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2, acmi000162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bes, M.; Freney, J.; Etienne, J.; Guerin-Faublee, V. Isolation of Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans from two cases of canine pyoderma. Vet. Rec. 2002, 150, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.A.; Kania, S.A.; Hnilica, K.A.; Wilkes, R.P.; Bemis, D.A. Isolation of Staphylococcus schleiferi from dogs with pyoderma. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 222, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, M.; Roberts, L.; Jones, M.; Young, V. Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans in companion animals. Vet. Rec. 2007, 161, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, B.; Varges, R.; Martins, R.; Martins, G.; Lilenbaum, W. In vitro antimicrobial resistance of staphylococci isolated from canine urinary tract infection. Can. Vet. J. 2010, 51, 738–742. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, T.; Shibata, S.; Murayama, N.; Nagathifuji, K.; Iwasaki, T.; Fukata, T. Antimicrobial susceptibility and methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. coagulans isolated from dogs with pyoderma in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2010, 72, 1615–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, C.; Morris, D.; O’Shea, K.; Rankin, S. Genotypic relatedness and phenotypic characterization of Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies in clinical samples from dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2011, 72, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Cawley, J.; Irizarry-Alvarado, J.; Alvarez, A.; Alvarez, S. Case of Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans endocarditis and metastatic infection in an immune compromised host. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2007, 9, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, E.; Boucher, H.; DeNofrio, D.; Pham, D.; Snydman, D. First report of a left ventricular assist device infection caused by Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans: A coagulase-positive organism. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 74, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzamalis, A.; Chalvatzis, N.; Anastasopoulos, E.; Tzetzi, D.; Dimitrakos, S. Acute postoperative Staphylococcus schleiferi endophthalmitis following uncomplicated cataract surgery: First report in the literature. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 23, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, A.; Shivpuri, D.; Sood, S. Staphylococcus schleiferi meningitis in a child. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarbrough, M.; Hamad, Y.; Burnham, C.; George, I. The brief case: Bacteremia and vertebral osteomyelitis due to Staphylococcus schleiferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 3157–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pomba, C.; Rantala, M.; Greko, C.; Baptiste, K.E.; Catry, B.; van Duijkeren, E.; Mateus, A.; Moreno, M.A.; Pyörälä, S.; Ružauskas, M.; et al. Public health risk of antimicrobial resistance transfer from companion animals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, J.; Smith, J.; Erol, E.; Locke, S.; Phillips, E.; Carter, C.; Odoi, A. Temporal trends and predictors of antimicrobial resistance among Staphylococcus spp. isolated from canine specimens submitted to a diagnostic laboratory. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, S.; Williamson, N.; Frank, L.; Wilkes, R.; Jones, R.; Bemis, D. Methicillin resistance of staphylococci isolated from the skin of dogs with pyoderma. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2004, 65, 1265–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, E.R.; Hnilica, K.A.; Frank, L.A.; Jones, R.D.; Bemis, D.A. Isolation of Staphylococcus schleiferi from healthy dogs and dogs with otitis, pyoderma, or both. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2005, 227, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; O’Shea, K.; Morris, D.; Robb, A.; Morrison, D.; Rankin, S. A real-time PCR assay to detect the Panton Valentine Leukocidin toxin in staphylococci: Screening Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans strains from companion animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2005, 107, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.; Rook, K.; Shofer, F.; Rankin, S. Screening of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus intermedius, and Staphylococcus schleiferi isolates obtained from small companion animals for antimicrobial resistance: A retrospective review of 749 isolates (2003-04). Vet. Dermatol. 2006, 17, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Kania, S.; Rohrbach, B.; Frank, L.; Bemis, D. Prevalence of oxacillin- and multidrug-resistant staphylococci in clinical samples from dogs: 1772 samples (2001–2005). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2007, 230, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detwiler, A.; Bloom, P.; Petersen, A.; Rosser, E. Multi-drug and methicillin resistance of staphylococci from canine patients at a veterinary teaching hospital (2006–2011). Vet. Q. 2013, 33, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunder, D.; Cain, C.; O’Shea, K.; Cole, S.; Rankin, S. Genotypic relatedness and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus schleiferi in clinical samples from dogs in different geographic regions of the United States. Vet. Dermatol. 2015, 26, 406-e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, C.; Morris, D.; Rankin, S. Clinical characterization of Staphylococcus schleiferi infections and identification of risk factors for acquisition of oxacillin-resistant strains in dogs: 225 cases (2003–2009). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2011, 39, 1566–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdovc, I.; Ocepek, M.; Pirs, T.; Krt, B.; Pinter, L. Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. coagulans, isolated from dogs and possible misidentification with other canine coagulase-positive staphylococci. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 2004, 51, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.; Barley, J. Staphylococcus schleiferi subspecies coagulans in dogs. Vet. Rec. 2007, 161, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, M.; Tognetti, R.; Pretti, C.; Crema, F.; Soldani, G.; Meucci, V.; Intorre, L. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus intermedius and Staphylococcus schleiferi isolated from dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2009, 87, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, N.; Monchique, C.; Belas, A.; Marques, C.; Gama, L.T.; Pomba, C. Trends and molecular mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in clinical staphylococci isolated from companion animals over a 16 year period. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens, P.; Vogelnest, L.; Ewen, E.; Bosward, K.; Norris, J. Canine superficial bacterial pyoderma: Evaluation of skin surface sampling methods and antimicrobial susceptibility of causal Staphylococcus isolates. Aust. Vet. J. 2014, 92, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penna, B.; Varges, R.; Medeiros, L.; Martins, G.; Martins, R.; Lilenbaum, W. Species distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility of staphylococci isolated from canine otitis externa. Vet. Dermatol. 2010, 21, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Lee, H.; Hwang, S.; Hong, J.; Lyoo, K.; Yang, S. Carriage of Staphylococcus schleiferi from canine otitis externa: Antimicrobial resistance profiles and virulence factors associated with skin infection. J. Vet. Sci. 2019, 20, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaminami, H.; Okamura, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Wajima, T.; Murayama, N.; Noguchi, N. Prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant staphylococci in nares and affected sites of pet dogs with superficial pyoderma. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanchaithong, P.; Perreten, V.; Schwendener, S.; Tribuddharat, C.; Chongthaleong, A.; Niyomtham, W.; Prapasarakul, N. Strain typing and antimicrobial susceptibility of methicillin-resistant coagulase-positive staphylococcal species in dogs and people associated with dogs in Thailand. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huse, H.K.; Miller, S.A.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Hindler, J.A.; Lawhon, S.D.; Bemis, D.A.; Westblade, L.F.; Humphries, R.M. Evaluation of oxacillin and cefoxitin disk diffusion and MIC breakpoints established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for detection of mecA-mediated oxacillin resistance in Staphylococcus schleiferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01653-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intorre, L.; Vanni, M.; Di Bello, D.; Pretti, C.; Meucci, V.; Tognetti, R.; Soldani, G.; Cardini, G.; Jousson, O. Antimicrobial susceptibility and mechanism of resistance to fluoroquinolones in Staphylococcus intermedius and Staphylococcus schleiferi. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 30, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.F.; Cain, C.L.; Brazil, A.M.; Rankin, S.C. Two coagulase-negative staphylococci emerging as potential zoonotic pathogens: Wolves in sheep’s clothing? Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Tsubakishita, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Sakusabe, A.; Ohtsuka, M.; Hirotaki, S.; Kawakami, T.; Fukata, T.; Hiramatsu, K. Multiplex-PCR method for species identification of coagulase-positive staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals, 5th ed.; CLSI Supplement VET01S; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, v11.0. 2021. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Kronvall, G.; Kahlmeter, G.; Myhre, E.; Galas, M.F. A new method for normalized interpretation of antimicrobial resistance from disk test results for comparative purposes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K.M.; Waisglass, S.E.; Dick, H.L.; Weese, J.S. Prevalence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) from skin and carriage sites of dogs after treatment of their meticillin-resistant or meticillin-sensitive staphylococcal pyoderma. Vet. Dermatol. 2012, 23, 369-e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, B.; Mendes, W.; Rabello, R.; Lilenbaum, W. Carriage of methicillin susceptible and resistant Staphylococcus schleiferi among dog with or without topic infections. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 162, 298–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, E.R.; Kinyon, J.M.; Noxon, J.O. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus schleiferi from healthy dogs and dogs with otitis, pyoderma or both. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 160, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.; Kruger, J.M.; Schall, W.; Beal, M.; Manning, S.D.; Kaneene, J.B. Acquisition and persistence of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria isolated from dogs and cats admitted to a veterinary teaching hospital. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 243, 990–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Feßler, A.T.; Loncaric, I.; Wu, C.; Kadlec, K.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J. Antimicrobial resistance among staphylococci of animal origin. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Devesa, J.; Hill, P.; Silva, V.; Poeta, P. Treatment of selected canine dermatological conditions in Portugal—A research survey. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 62, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicine Agency (EMA). Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption, 2020. ‘Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial agents in 31 European Countries in 2018′. (EMA/24309/2020); European Medicine Agency (EMA): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou, K.; Foka, A.; Petinaki, E.; Jelastopulu, E.; Dimitracopoulos, G.; Spiliopoulou, I. Comparison of two commercial methods with PCR restriction fragment lengt polymorphism of the tuf gene in the identification of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 43, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.T.; Lubbers, B.V.; Schwarz, S.; Watts, J.L. Applying definitions for multidrug resistance, extensive drug resistance and pandrug resistance to clinically significant livestock and companion animal bacterial pathogens. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronvall, G.; Smith, P. Normalized resistance interpretation, the NRI method: Review of NRI disc test applications and guide to calculations. Apmis 2016, 124, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). MIC Distributions and Epidemiological Cut-Off Values (ECOFF) Setting; EUCAST SOP 10.1; The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST): Växjö, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, M.; de Lencastre, H.; Matthews, P.; Tomasz, A.; Adamsson, I.; Aires de Sousa, M.; Camou, T.; Cocuzza, C.; Corso, A.; Couto, I.; et al. Multilaboratory Project Collaborators. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: Comparison of results obtained in a multilaboratory effort using identical protocols and MRSA strains. Microb. Drug Resist. 2000, 6, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriço, J.A.; Pinto, F.R.; Simas, C.; Nunes, S.; Sousa, N.G.; Frazão, N.; de Lencastre, H.; Almeida, J.S. Assessment of band-based similarity coefficients for automatic type and subtype classification of microbial isolates analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 5483–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carriço, J.A.; Silva-Costa, C.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Pinto, F.R.; de Lencastre, H.; Almeida, J.S.; Ramirez, M. Illustration of a common framework for relating multiple typing methods by application to macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 2524–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibiotic | ZD Breakpoint | Number of Isolates (%) | Resistance Determinants (No. Isolates) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (mm) | R (mm) | S | I | R | ||

| Penicillin ** | ≥29 a | ≤28 a | 10 (37.0%) | - | 17 (63.0%) | blaZ (16) and/or mecA (2) |

| Oxacillin ** | ≥18 | ≤17 | 25 (92.6%) | - | 2 (7.4%) | mecA (2) |

| Enrofloxacin * | ≥23 | ≤16 | 16 (59.3%) | 2 (7.4%) | 9 (33.3%) | QRDR mutations: GrlA [S80I, S80R, S80G]; GyrA [S80F, S80Y, E88A, E88G] |

| Ciprofloxacin ** | ≥21 | ≤15 | 17 (63.0%) | 4 (14.8%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| Moxifloxacin ** | ≥24 | ≤20 | 21 (77.8%) | 2 (7.4%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Erythromycin ** | ≥23 | ≤13 | 24 (88.9%) | 2 (7.4%) | 1 (3.7%) | erm(B) (1) |

| Clindamycin * | ≥21 | ≤14 | 24 (88.9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (11.1%) | erm(B) (1) |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin *** | ≥21 | <18 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Tetracycline * | ≥23 | ≤17 | 26 (96.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.7%) | - |

| Minocycline ** | ≥19 | ≤14 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Tigecycline *** | ≥19 | <19 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Fusidic acid *** | ≥24 | <24 | 25 (92.6%) | - | 2 (7.4%) | - |

| Linezolid ** | ≥21 | ≤20 | 27 (100%) | - | 0 (0%) | - |

| Chloramphenicol ** | ≥18 | ≤12 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole ** | ≥16 | ≤10 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Rifampicin ** | ≥20 | ≤16 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Gentamicin ** | ≥15 | ≤12 | 27 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Amikacin *** | ≥18 | <18 | 27 (100%) | - | 0 (0%) | - |

| Tobramycin *** | ≥18 | <18 | 27 (100%) | - | 0 (0%) | - |

| Kanamycin *** | ≥18 | <18 | 27 (100%) | - | 0 (0%) | - |

| COWT (mm) | SD (mm) | WT Population (mm) | NWT Population (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apramycin | 18 | 2.11 | ≥18 | <18 |

| Bacitracin | 13 | 1.85 | ≥13 | <13 |

| Florfenicol | 22 | 2.64 | ≥22 | <22 |

| Mupirocin | 32 | 3.21 | ≥32 | <32 |

| Neomycin | 18 | 2.20 | ≥18 | <18 |

| Novobiocin | 30 | 1.53 | ≥30 | <30 |

| Isolate | Identification | Biological Sample | Year | Laboratory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIOS-V1 * | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2015 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V2 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2012 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V3 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2014 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V9 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V35 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V41 | S. coagulans | perianal skin swab | 2018 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V42 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2001 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V43 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2004 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V44 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2005 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V45 | S. coagulans | perianal fistula swab | 2008 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V46 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 1999 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V47 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2003 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V51 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2007 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V91 | S. coagulans | axillar skin swab | 2004 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V93 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2007 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V94 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2007 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V95 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2013 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V98 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2015 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V107 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2015 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V126 * | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2016 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V139 | S. schleiferi | skin swab | 2016 | Lab1 |

| BIOS-V191 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab2 |

| BIOS-V205 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab2 |

| BIOS-V209 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab2 |

| BIOS-V232 | S. coagulans | epidermal collarette | 2018 | Lab2 |

| BIOS-V243 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab2 |

| BIOS-V265 | S. coagulans | skin swab | 2018 | Lab2 |

| BIOS-V289 | S. coagulans | Interdigital skin swab | 2018 | Lab2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costa, S.S.; Oliveira, V.; Serrano, M.; Pomba, C.; Couto, I. Phenotypic and Molecular Traits of Staphylococcus coagulans Associated with Canine Skin Infections in Portugal. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10050518

Costa SS, Oliveira V, Serrano M, Pomba C, Couto I. Phenotypic and Molecular Traits of Staphylococcus coagulans Associated with Canine Skin Infections in Portugal. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(5):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10050518

Chicago/Turabian StyleCosta, Sofia Santos, Valéria Oliveira, Maria Serrano, Constança Pomba, and Isabel Couto. 2021. "Phenotypic and Molecular Traits of Staphylococcus coagulans Associated with Canine Skin Infections in Portugal" Antibiotics 10, no. 5: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10050518

APA StyleCosta, S. S., Oliveira, V., Serrano, M., Pomba, C., & Couto, I. (2021). Phenotypic and Molecular Traits of Staphylococcus coagulans Associated with Canine Skin Infections in Portugal. Antibiotics, 10(5), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10050518