Beta-Lactam vs. Fluoroquinolone Monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria and Definitions

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Screening and Methodological Assessment

2.4. Data Collection and Outcomes Assessed

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

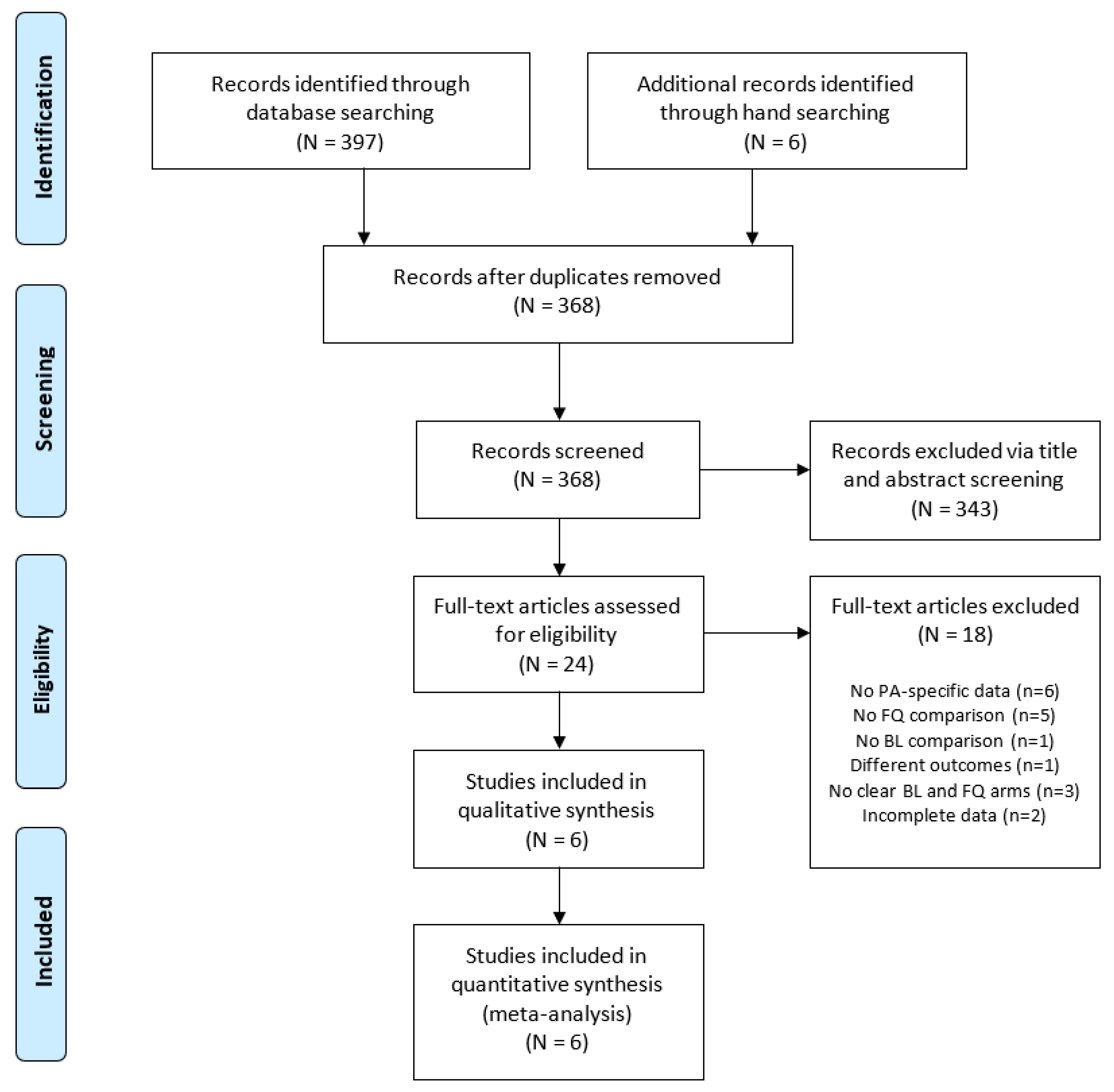

3.1. Selected Studies

3.2. Methodological Quality of Studies

3.3. Study Characteristics

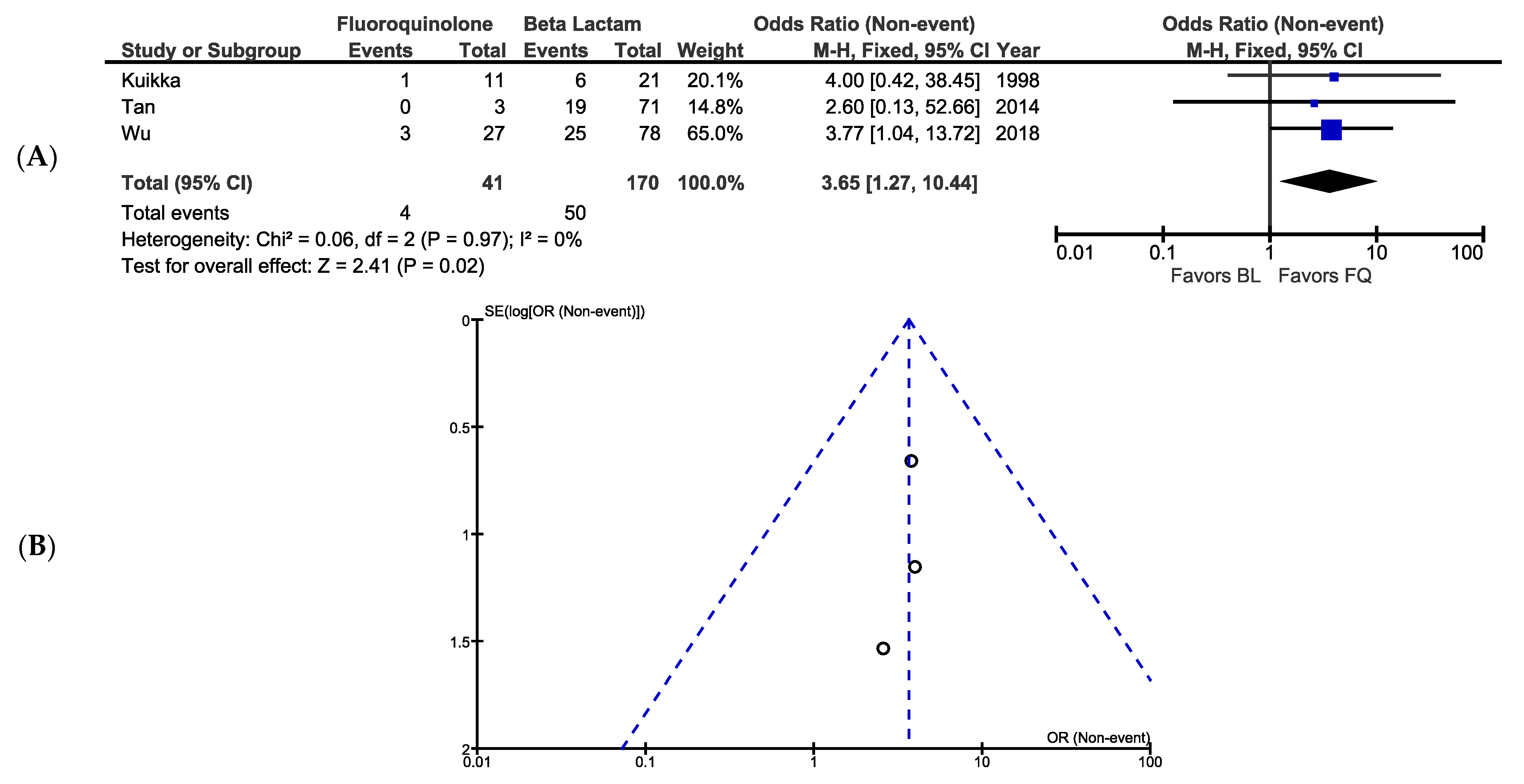

3.4. Mortality

3.5. Bacteriological Eradication

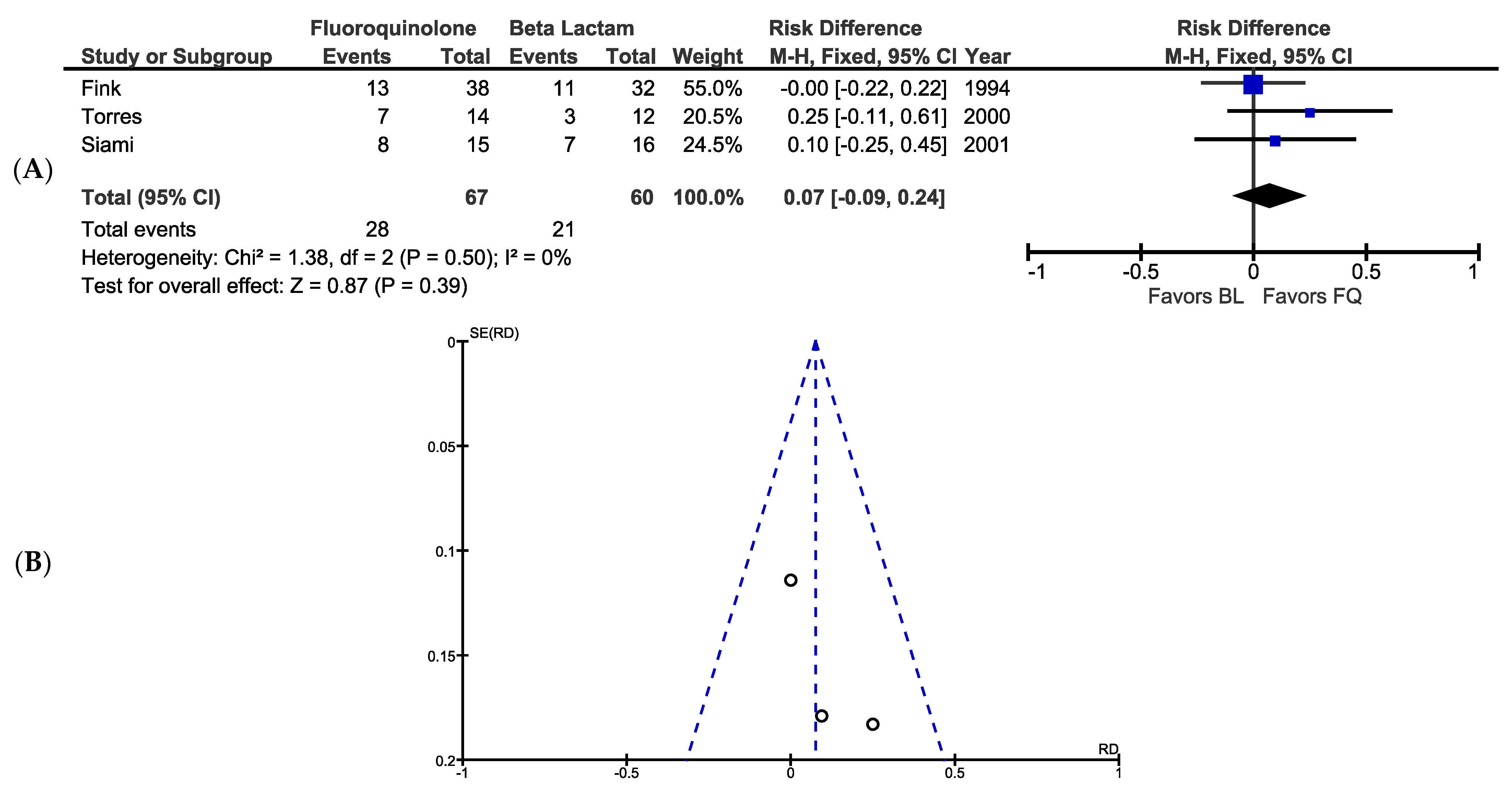

3.6. Clinical Success

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhanel, G.G.; Clark, N.; Lynch, J.P. Emergence of Antimicrobial Resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Implications for Therapy. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 38, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, A.; Mulet, X.; López-Causapé, C.; Juan, C. The increasing threat of Pseudomonas aeruginosa high-risk clones. Drug Resist. Updates 2015, 21–22, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Garbajosa, P.; Cantón, R. Epidemiology of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Implications for empiric and definitive therapy. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 2017, 30, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Magill, S.S.; Edwards, J.R.; Bamberg, W.; Beldavs, Z.G.; Dumyati, G.; Kainer, M.A.; Lynfield, R.; Maloney, M.; McAllister-Hollod, L.; Nadle, J.; et al. Multistate Point-Prevalence Survey of Health Care–Associated Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point Prevalence Survey of Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use in European Acute Care Hospitals; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Dept of Health and Human Services. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013.

- Mulani, M.S.; Kamble, E.; Kumkar, S.N.; Tawre, M.S.; Pardesi, K.R. Emerging Strategies to Combat ESKAPE Pathogens in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.W.; Khan, A.U. Updates on the pathogenicity status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, E.; Cots, F.; Sala, M.; Comas, M.; Belvis, F.; Riu, M.; Salvadó, M.; Grau, S.; Horcajada, J.P.; Montero, M.M.; et al. Hospital costs of nosocomial multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bassetti, M.; Vena, A.; Croxatto, A.; Righi, E.; Guery, B. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Drugs Context 2018, 7, 212527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Cosgrove, S.E.; Maragakis, L.L. Combination Therapy for Treatment of Infections with Gram-Negative Bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 450–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, T.; Gerding, D.N. Aminoglycosides versus beta-lactams in gram-negative pneumonia. Semin. Respir. Infect. 1991, 6, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, M.; Yahav, D.; Bivas, A.; Fraser, A.; Leibovici, L. Anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams for the initial, empirical, treatment of febrile neutropenia: Comparison of beta-lactams. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.D.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falagas, M.E.; Vardakas, K.Z.; Tansarli, G.S.; Bliziotis, I.A. Beta-lactam plus aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone combination versus -lactam monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools. National Institute of Health: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 11 July 2019).

- Kuikka, A.; Valtonen, V.V. Factors associated with improved outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in a Finnish university hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1998, 17, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Teng, C.B.; Ng, T.M.; Lye, D.C.B. Antibiotic therapy and clinical outcomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) bacteraemia. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2014, 43, 526–534. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.-F.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wang, F.-D.; Yang, T.-C.; Fung, C.-P. Is fluoroquinolone monotherapy a useful alternative treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia? Infection 2018, 46, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, M.P.; Snydman, D.; Niederman, M.S.; Leeper, K.V.; Johnson, R.H.; Heard, S.O.; Wunderink, R.G.; Caldwell, J.W.; Schentag, J.J.; Siami, G.A. Treatment of severe pneumonia in hospitalized patients: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial comparing intravenous ciprofloxacin with imipenem-cilastatin. The Severe Pneumonia Study Group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, A.; Bauer, T.T.; León-Gil, C.; Castillo, F.; Alvarez-Lerma, F.; Martínez-Pellús, A.; Leal-Noval, S.R.; Nadal, P.; Palomar, M.; Blanquer, J.; et al. Treatment of severe nosocomial pneumonia: A prospective randomised comparison of intravenous ciprofloxacin with imipenem/cilastatin. Thorax 2000, 55, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siami, G.; Christou, N.; Eiseman, I.; Tack, K.J. The Clinafloxacin Severe Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Study Group. Clinafloxacin versus Piperacillin-Tazobactam in Treatment of Patients with Severe Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 29th Informational Supplement; M100-S29; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rhomberg, P.; Jones, R.N. Summary trends for the Meropenem Yearly Susceptibility Test Information Collection Program: A 10-year experience in the United States (1999–2008). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 65, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, C.; Köhler, T.; Patry, I.; Dehecq, B.; Van Delden, C.; Plésiat, P. Role of the MexEF-OprN Efflux System in Low-Level Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5676–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Study, Year | Study Design; Record Years | Study Location; Setting | Quality Rating | Infection Type; Mode of Acquisition | Outcomes | Patient Demographics b | BL Arm: # of Patients; Drugs | FQ Arm: # of Patients; Drugs | Polymicrobial Infections | Pertinent Definitions ⌿ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuikka et al., 1998 [17] | Cohort, retro; 1976–1982 & 1992–1996 | Finland; Hospital (inpatients) | Fair | Bacteremia w/sepsis; nosocomial (90%) & community acquired | 30 d mortality | 63% male, 46% >60 y/o, 34% hematologic malignancy, 16% nonhematologic malignancy, 30% ICU; 37% systemic corticosteroid therapy; 35% cytotoxic therapy | 21; carbenicillin, pipercillin (+tazobactam), ceftazidime, imipenem, meropenem | 11; ciprofloxacin | N (for bacteremia), 24% other infection | Definitive therapy = 7 d or until death |

| Tan et al., 2014 [18] | Cohort, retro; 2007–2008 | Singapore; Hospital (inpatients) | Fair | Bacteremia; nosocomial (45%), healthcare-associated (32%), community acquired (23%) | 30 d mortality | 59% male, 65 median age, 30 median SAPS II score, 1 median Pitt bacteremia score, 18% ICU, 44% active empirical therapy, 19% cancer, 9% HIV/AIDS | 71; ceftazidime, piperacillin-tazobactam, carbapenems, piperacillin, aztreonam | 3; ciprofloxacin | Y, 19% of patients receiving monotherapy | Definitive therapy = 2 d after culture results |

| Wu et al., 2018 [19] | Cohort, retro; 2013–2014 | Taiwan; Hospital (inpatients) | Good | Bacteremia; nosocomial (66%), healthcare-associated (24%), community acquired (8%) | 28 d mortality | 71% male, 66 mean age, 64% malignancy, 21 mean APACHE II score, 43% septic shock, 3 mean Pitt bacteremia score; 30% chemotherapy, 17% steroid use, 16% neutopenia, 79% appropriate empirical therapy | 78; piperacillin-tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem-cilastatin, meropenem, doripenem | 27; ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin IV or PO | N | Definitive therapy = >3 d & for >50% of treatment time |

| Fink et al., 1994 [20] | Randomized control, DB; 1990- 1992 | USA; Hospital (inpatients) | Good | Severe pneumonia; nosocomial (78%) & community acquired | Bacteriological eradication | 70% male, 59 mean age, 79% ICU, 17.6 mean APACHE II score, 15% bacteremia | 32 *; imipenem-cilastatin v | 38 *; ciprofloxacin m,v | Y, 50% of non-ITT population | Bacteriological eradication = eradication + presumed eradication |

| Torres et al., 2000 [21] | Randomized control, OL; NR | Spain; Hospital (inpatients) | Fair | Severe pneumonia; nosocomial | Bacteriological eradication, clinical response | 74% male, 62 mean age, 13.8 mean APACHE II score | 12; imipenem-cilastatin | 14; ciprofloxacin | Y, 24% of microbiologically and clinically evaluable population | Bacteriological eradication = eradication + presumed eradication; Clinical success = cure +improvement |

| Siami et al., 2001 [22] | Randomized control, IB; NR | USA & Canada; Hospital (inpatients a) | Poor | Severe SSTI (includes spontaneous, wound, and diabetic foot); NR | Bacteriological eradication | 71% male, 53 median age, 41% spontaneous, 38% wound, 18% diabetic foot | 16; piperacillin-tazobactam v w/PO option (amoxicillin-clavulanate) after 3 d | 15; clinafloxacin w/PO option after 3 d | Y, 55% | Bacteriological eradication = eradication + presumed eradication |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reid, E.; Walters, R.W.; Destache, C.J. Beta-Lactam vs. Fluoroquinolone Monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121483

Reid E, Walters RW, Destache CJ. Beta-Lactam vs. Fluoroquinolone Monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(12):1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121483

Chicago/Turabian StyleReid, Eric, Ryan W. Walters, and Christopher J. Destache. 2021. "Beta-Lactam vs. Fluoroquinolone Monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Antibiotics 10, no. 12: 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121483

APA StyleReid, E., Walters, R. W., & Destache, C. J. (2021). Beta-Lactam vs. Fluoroquinolone Monotherapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics, 10(12), 1483. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10121483