Resistance Trend Estimation Using Regression Analysis to Enhance Antimicrobial Surveillance: A Multi-Centre Study in London 2009–2016

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Need of Local AMR Surveillance

1.1.1. Measuring Resistance from Susceptibility Data

1.1.2. Evaluating Tendency on Time Series Signals

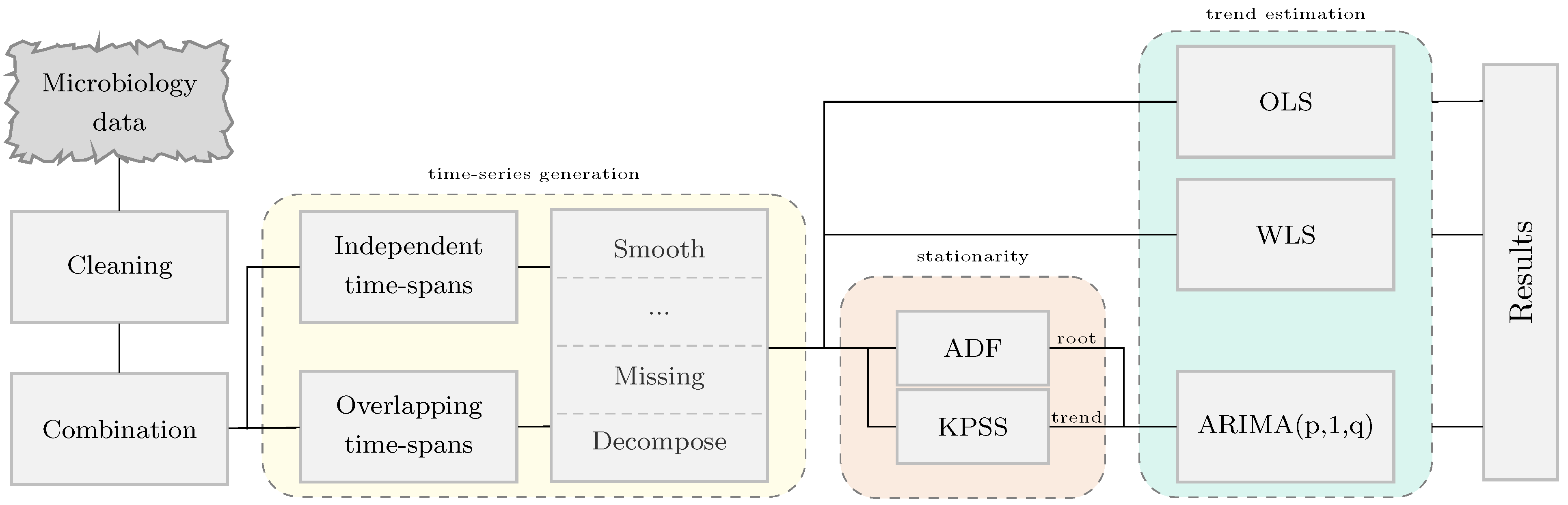

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbiology Data

2.2. Attributes in a Susceptibility Test Record

2.3. Generation of Resistance Time Series Signals

2.4. Regression Analysis for Trend Estimation

2.4.1. Least Squares Regression

2.4.2. Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. Trend and Stationarity in Time Series

2.5.2. Statistical Significance among Regression Methods

2.5.3. Pearson Correlation Coefficient

2.6. Software

3. Results

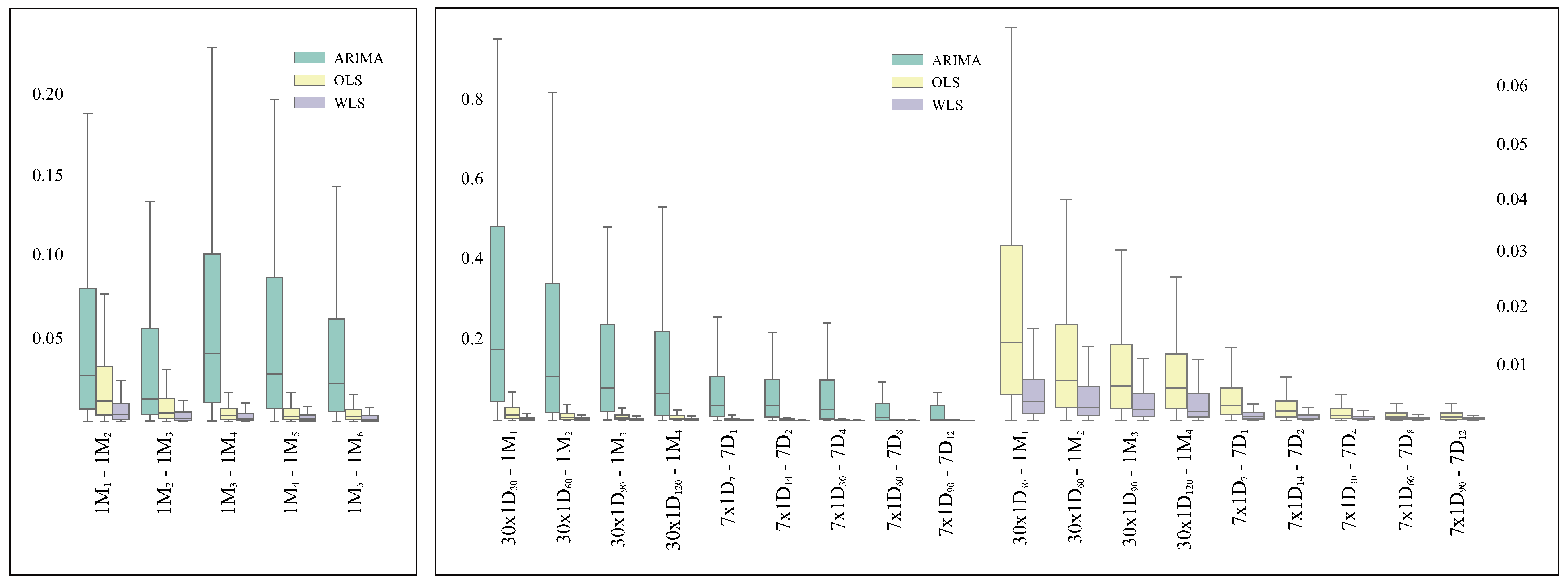

3.1. Analysis of the Robustness of the Methods

3.1.1. Consistency on Consecutive Time Spans

3.1.2. Consistency on Granularity

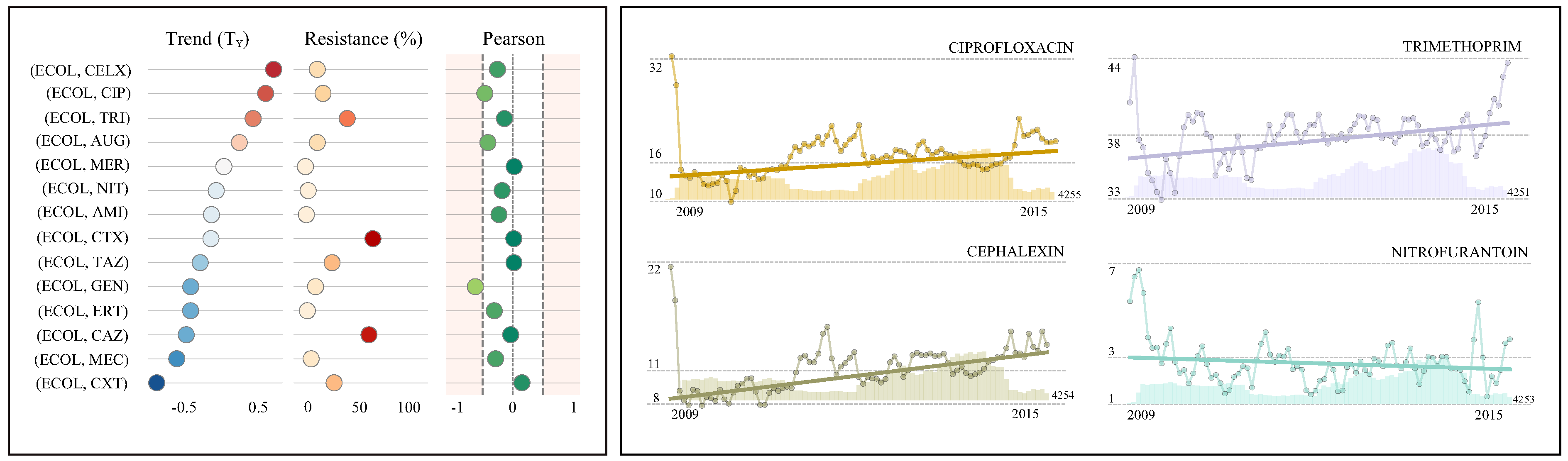

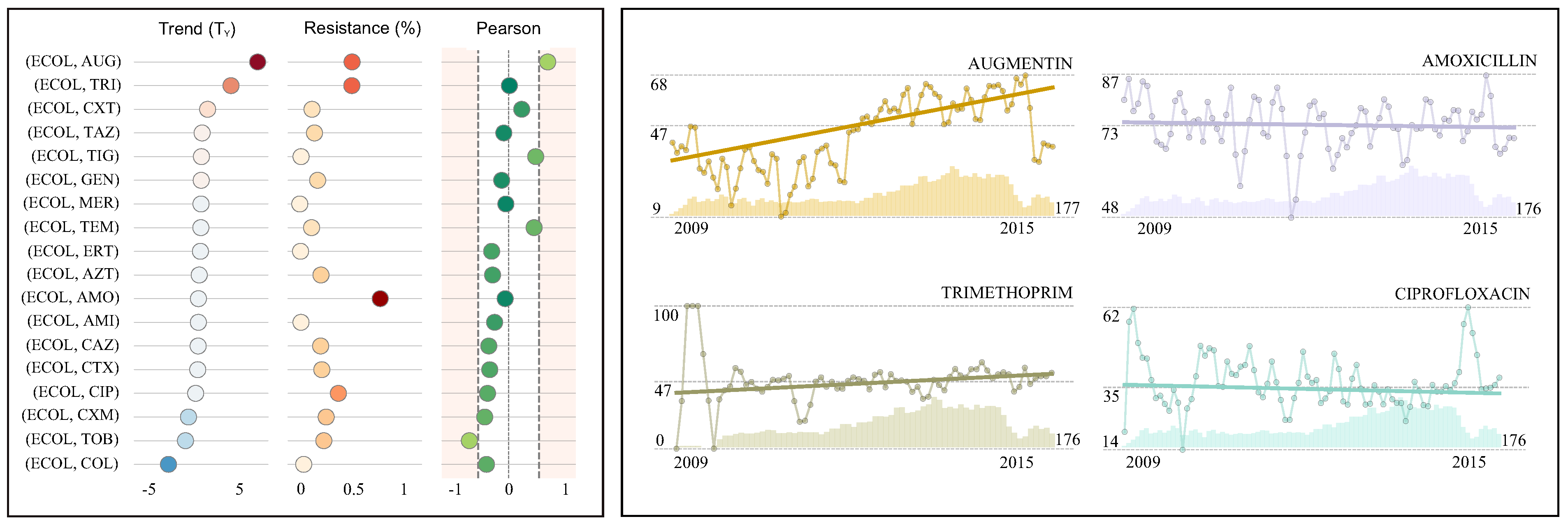

3.2. AMR Surveillance: Case Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Case Study I: Escherichia coli in Urine Samples

4.2. Case Study II: Escherichia coli in Blood Samples

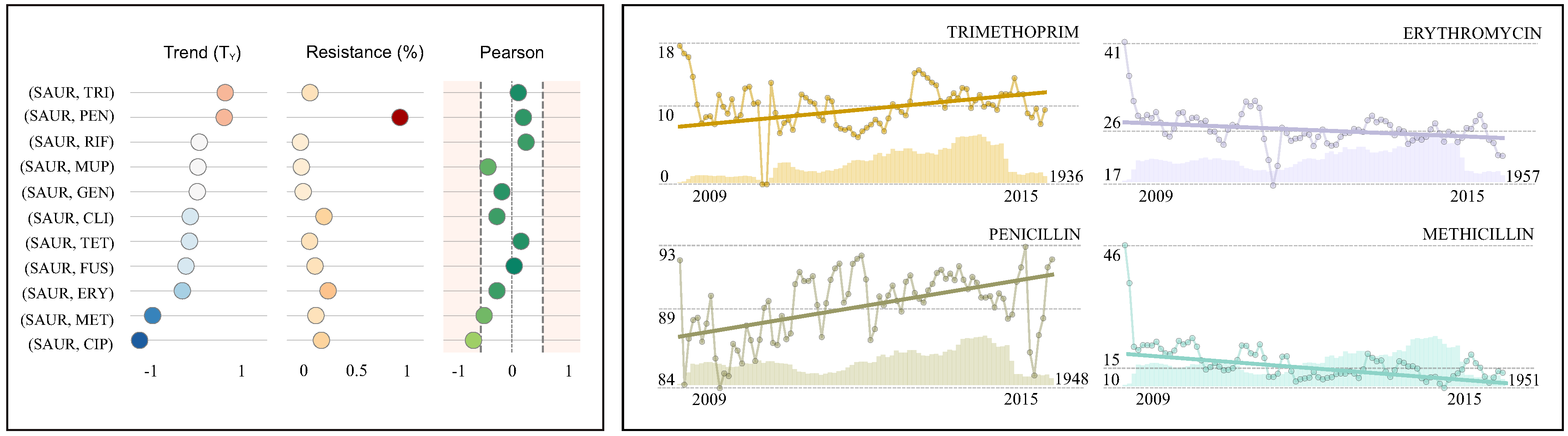

4.3. Case Study III: Staphylococcus aureus in Wound Samples

4.4. Susceptibility Testing: Behaviour and Guidelines

4.5. Advantages of Overlapping Time Intervals in Surveillance

4.6. The Importance of Surveillance Data

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADF | Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| AMS | Antimicrobial Stewardship |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| ARMA | Autoregressive Moving-Average |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| ECOL | Escherichia coli |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| KPSS | Kwiatkowski-Phillips-Schmidt-Shin |

| MA | Moving Average |

| MALDI-TOF | Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time Of Flight |

| MARI | Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance Index |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MRSA | Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| SARI | Single Antimicrobial Resistance Index |

| SARIMA | Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SART | Single Antimicrobial Resistance Trend |

| SAUR | Staphylococcus aureus |

| VARIMA | Vector Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| WLS | Weighted Least Squares |

References

- O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Rev. Antimicrob. Resist. 2014, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A. Epistasis and the evolution of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holmes, A.H.; Moore, L.S.; Sundsfjord, A.; Steinbakk, M.; Regmi, S.; Karkey, A.; Guerin, P.J.; Piddock, L.J. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 2016, 387, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collignon, P.; Athukorala, P.c.; Senanayake, S.; Khan, F. Antimicrobial resistance: The major contribution of poor governance and corruption to this growing problem. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Public Health England. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR); Annual Report 2017; PHE: London, UK, 2017.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe 2016; Annual report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net); ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) Report: Early Implementation 2016–2017; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, L.S.P.; Freeman, R.; Gilchrist, M.J.; Gharbi, M.; Brannigan, E.T.; Donaldson, H.; Livermore, D.M.; Holmes, A.H. Homogeneity of antimicrobial policy, yet heterogeneity of antimicrobial resistance: Antimicrobial non susceptibility among 108717 clinical isolates from primary, secondary and tertiary care patients in London. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawson, T.M.; Wilson, R.C.; O’Hare, D.; Herrero, P.; Kambugu, A.; Lamorde, M.; Ellington, M.; Georgiou, P.; Cass, A.; Hope, W.W.; et al. Optimizing antimicrobial use: Challenges, advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littmann, J.; Viens, A. The ethical significance of antimicrobial resistance. Public Health Ethics 2015, 8, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pulcini, C.; Williams, F.; Molinari, N.; Davey, P.; Nathwani, D. Junior doctors’ knowledge and perceptions of antibiotic resistance and prescribing: A survey in France and Scotland. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011, 17, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, A.T.; Roque, F.; Falcão, A.; Figueiras, A.; Herdeiro, M.T. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, M.P.; Loneragan, G.H.; Scott, H.M.; Singer, R.S. Antimicrobial resistance: Challenges and perspectives. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.; Charani, E.; Moore, L.S.P.; Hernandez, B.; Castro-Sánchez, E.; Herrero, P.; Georgiou, P.; Holmes, A.H. Mapping the decision pathways of acute infection management in secondary care among UK medical physicians: A qualitative study. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charani, E.; Edwards, R.; Sevdalis, N.; Alexandrou, B.; Sibley, E.; Mullett, D.; Franklin, B.D.; Holmes, A. Behavior change strategies to influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care: A systematic review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davey, P.; Brown, E.; Charani, E.; Fenelon, L.; Gould, I.M.; Holmes, A.; Ramsay, C.R.; Wiffen, P.J.; Wilcox, M. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Libr. 2017, 2, 003543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pinder, R.; Berry, D.; Sallis, A.; Chadborn, T. Antibiotic Prescribing and Behaviour Change in Healthcare Settings: Literature Review and Behavioural Analysis; Department of Health & Public Health England: London, UK, 2015.

- Elias, C.; Moja, L.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M.; Forte, G.; Magrini, N. Guideline recommendations and antimicrobial resistance: The need for a change. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nair, S.; Hsu, D.; Celi, L.A. Challenges and Opportunities in Secondary Analyses of Electronic Health Record Data. In Secondary Analysis of Electronic Health Records; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Department of Health. UK Five Year Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy: 2013 to 2018; Department of Health: London, UK, 2013.

- Goldmann, D.A.; Weinstein, R.A.; Wenzel, R.P.; Tablan, O.C.; Duma, R.J.; Gaynes, R.P.; Schlosser, J.; Martone, W.J.; Acar, J.; Avorn, J.; et al. Strategies to prevent and control the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms in hospitals: A challenge to hospital leadership. J. Am. Med Assoc. (JAMA) 1996, 275, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggan, J.C.; Navar-Boggan, A.M.; Jhaveri, R. Pediatric-specific antimicrobial susceptibility data and empiric antibiotic selection. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e615–e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bielicki, J.A.; Sharl, M.; Johnson, A.P.; Henderson, K.L.; Cromwell, D.A.; Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children Project; Berger, C.; Esposito, S.; Danieli, E.; Tenconi, R.; et al. Selecting appropriate empirical antibiotic regimens for paediatric bloodstream infections: Application of a Bayesian decision model to local and pooled antimicrobial resistance surveillance data. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koningstein, M.; van der Bij, A.K.; de Kraker, M.E.; Monen, J.C.; Muilwijk, J.; de Greeff, S.C.; Geerlings, S.E.; Leverstein-van Hall, M.A.; ISIS-AR Study Group. Recommendations for the empirical treatment of complicated urinary tract infections using surveillance data on antimicrobial resistance in the Netherlands. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mehl, A.; Åsvold, B.O.; Kümmel, A.; Lydersen, S.; Paulsen, J.; Haugan, I.; Solligård, E.; Damås, J.K.; Harthug, S.; Edna, T.H. Trends in antimicrobial resistance and empiric antibiotic therapy of bloodstream infections at a general hospital in Mid-Norway: A prospective observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Krumperman, P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, A.P. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 2015, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rossolini, G.; Mantengoli, E. Antimicrobial resistance in Europe and its potential impact on empirical therapy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agodi, A.; Barchitta, M.; Quattrocchi, A.; Maugeri, A.; Aldisio, E.; Marchese, A.E.; Mattaliano, A.R.; Tsakris, A. Antibiotic trends of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii resistance indicators in an intensive care unit of Southern Italy, 2008–2013. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2015, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seber, G.A.; Lee, A.J. Linear Regression Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 329. [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell, P.J.; Davis, R.A. Introduction to Time Series and Forecasting; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations: Quality and Consistency in Clinical Laboratories; PHE: London, UK, 2014.

- British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. BSAC Methods fro Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Version 12; BSAC: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Waskom, M.; Botvinnik, O.; O’Kane, D.; Hobson, P.; Lukauskas, S.; Gemperline, D.C.; Augspurger, T.; Halchenko, Y.; Cole, J.B.; Warmenhoven, J.; et al. mwaskom/seaborn: V0.8.1 (September 2017). Zenodo 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.; Morrissey, I.; De Rubeis, D.; Robbins, M.; Felmingham, D. A UK multicentre study of the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial pathogens causing urinary tract infection. J. Infect. 2003, 46, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahlmeter, G.; Åhman, J.; Matuschek, E. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli causing uncomplicated urinary tract infections: A European update for 2014 and comparison with 2000 and 2008. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2015, 4, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Public Health England. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR); Annual Report 2015; PHE: London, UK, 2015.

- Bean, D.C.; Krahe, D.; Wareham, D.W. Antimicrobial resistance in community and nosocomial Escherichia coli urinary tract isolates, London 2005–2006. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2008, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Public Health Wales. Antibacterial Resistance in Wales: 2006–2015; PHW: Cardiff, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR); Annual Report 2014; PHE: London, UK, 2014.

- Department of Health & Public Health England. Antimicrobial Resistance Empirical and Statistical Evidence-Based; PHE: London, UK, 2016.

- Fluit, A.C.; Jones, M.E.; Schmitz, F.J.; Acar, J.; Gupta, R.; Verhoef, J. Antimicrobial susceptibility and frequency of occurrence of clinical blood isolates in Europe from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program, 1997 and 1998. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 30, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisplinghoff, H.; Bischoff, T.; Tallent, S.M.; Seifert, H.; Wenzel, R.P.; Edmond, M.B. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: Analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dancer, S.J. Importance of the environment in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition: The case for hospital cleaning. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelkamp, C.H.; Maxon, T. Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to the Action of Penicillin. Exp. Biol. Med. 1942, 51, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.P.; Pearson, A.; Duckworth, G. Surveillance and epidemiology of MRSA bacteraemia in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 56, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, A.P.; Davies, J.; Guy, R.; Abernethy, J.; Sheridan, E.; Pearson, A.; Duckworth, G. Mandatory surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia in England: The first 10 years. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerver, S.; Mihalkova, M.; Abernethy, J.; Bou-Antoun, S.; Nsonwu, O.; Kauser, S.; Wasti, S.; Apraku, D.; Davies, J.; Hope, R. Annual Epidemiological Commentary: Mandatory MRSA, MSSA and E. coli Bacteraemia and C. Difficile Infection; Public Health England: London, UK, 2014.

- Hernandez, B.; Herrero, P.; Rawson, T.M.; Moore, L.S.P.; Charani, E.; Holmes, A.H.; Georgiou, P. Data-driven Web-based Intelligent Decision Support System for Infection Management at Point-Of-Care: Case-Based Reasoning Benefits and Limitations. In Proceedings of the 10th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies, Porto, Portugal, 21–23 February 2017; Volume 5, pp. 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, B.; Herrero, P.; Rawson, T.M.; Moore, L.S.P.; Evans, B.; Toumazou, C.; Holmes, A.H.; Georgiou, P. Supervised learning for infection risk inference using pathology data. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hernandez, B. Data-Driven Web-Based Intelligent Decision Support System for Infection Management at Point of Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.; Hernandez, B.; Moore, L.S.; Herrero, P.; Charani, E.; Ming, D.; Wilson, R.C.; Blandy, O.; Sriskandan, S.; Gilchrist, M.; et al. A real-world evaluation of a Case-Based Reasoning algorithm to support antimicrobial prescribing decisions in acute care. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, T.M.; Hernandez, B.; Moore, L.S.P.; Blandy, O.; Herrero, P.; Gilchrist, M.; Gordon, A.; Toumazou, C.; Sriskandan, S.; Georgiou, P.; et al. Supervised machine learning for the prediction of infection on admission to hospital: A prospective observational cohort study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 74, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

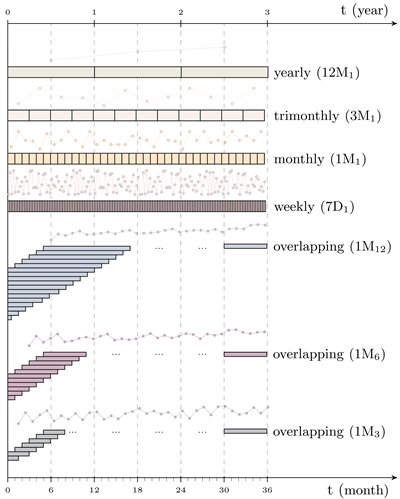

| Independent time intervals |  | |||

| This is the traditional method used in antimicrobial surveillance systems where the time spans considered are independent; that is, they do not overlap (e.g., month or year). | ||||

| Overlapping time intervals | ||||

| This method is defined as a fixed region which is moved across time to compute consecutive resistance indexes. It is described by two parameters; the length of the region (period) and the distance between consecutive windows (shift). | ||||

| Notation | ||||

| The notation to define the time series generation methodology use is shiftperiod. Some examples are presented below. | ||||

| shiftperiod | Shift | Period | Type | |

| 1D1 | Daily | previous day | I | |

| 7D1 | Weekly | previous week | I | |

| 1M1 | Monthly | previous month | I | |

| 12M1 | Yearly | previous year | I | |

| 1M12 | Monthly | previous year | O | |

| 1M6 | Monthly | previous 6 months | O | |

| 1M3 | Monthly | previous 3 months | O | |

| Antimicrobial | R(%) (95% CI) | References | TM(%) (95% CI) | References | TY(%) | Pearson | Isolates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cephalexin (CELX) | 11.1 | (10.9, 11.3) | 0.055 | (0.045, 0.065) | 0.7 | ↑ | −0.25 | 79,090 | ||

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 16.3 | (16.0, 16.5) | [39,40] | 0.046 | (0.031, 0.062) | [5,40] | 0.6 | ↑ | −0.46 | 79,239 |

| Trimethoprim (TRI) | 37.8 | (37.4, 38.1) | [39,40,41,42] | 0.033 | (0.020, 0.046) | [40] | 0.4 | ↑ | −0.14 | 79,133 |

| Augmentin (AUG) | 10.9 | (10.7, 11.2) | 0.018 | (−0.022, 0.059) | 0.2 | ↔ | −0.42 | 79,093 | ||

| Meropenem (MER) | 0.2 | (0.1, 0.3) | 0.002 | (−0.002, 0.006) | 0.0 | ↔ | 0.02 | 9875 | ||

| Nitrofurantoin (NIT) | 2.7 | (2.6, 2.8) | [39,40,41,42] | −0.006 | (−0.013, 0.001) | −0.1 | ↔ | −0.18 | 79,108 | |

| Amikacin (AMI) | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.2) | −0.011 | (−0.022, 0.000) | −0.1 | ↔ | −0.23 | 9786 | ||

| Cefotaxime (CTX) | 60.8 | (59.9, 61.8) | −0.012 | (−0.083, 0.059) | −0.1 | ↔ | 0.01 | 9803 | ||

| Tazocin (TAZ) | 24.2 | (23.3, 25.0) | [39] | −0.023 | (−0.078, 0.032) | −0.3 | ↔ | 0.01 | 9878 | |

| Gentamicin (GEN) | 9.3 | (9.1, 9.5) | [42] | −0.033 | (−0.061, −0.005) | −0.4 | ↓ | −0.62 | 63,399 | |

| Ertapenem (ERT) | 2.0 | (1.7, 2.3) | −0.033 | (−0.050, −0.017) | −0.4 | ↓ | −0.31 | 8882 | ||

| Ceftazidime (CAZ) | 57.3 | (53.3, 58.2) | −0.038 | (−0.113, 0.037) | −0.5 | ↔ | −0.04 | 9810 | ||

| Mecillinam (MEC) | 5.4 | (4.9, 5.8) | −0.048 | (−0.071, −0.024) | −0.6 | ↓ | −0.29 | 9083 | ||

| Cefoxitin (CXT) | 26.0 | (25.1, 26.8) | −0.069 | (−0.123, −0.016) | −0.8 | ↓ | 0.15 | 9798 | ||

| Antimicrobial | R(%) (95% CI) | References | TM(%) (95% CI) | References | TY(%) | Pearson | Isolates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Augmentin (AUG) | 47.5 | (45.8-49.2) | [5,41] | 0.359 | (0.249, 0.470) | [41] | 4.3 | ↓ | 0.64 | 3317 |

| Trimethoprim (TRI) | 47.2 | (45.4–49.1) | 0.190 | (0.079, 0.301) | 2.3 | ↓ | 0.01 | 2774 | ||

| Cefoxitin (CXT) | 11.5 | (10.4–12.6) | 0.041 | (−0.006, 0.089) | 0.5 | ↔ | 0.22 | 3316 | ||

| Tazocin (TAZ) | 13.7 | (12.6–14.9) | [5,41,43] | 0.006 | (−0.040, 0.052) | [5,41,43] | 0.1 | ↔ | −0.08 | 3321 |

| Tigecycline (TIG) | 1.7 | (1.2–2.2) | 0.002 | (−0.026, 0.030) | 0.0 | ↔ | 0.45 | 2734 | ||

| Gentamicin (GEN) | 16.6 | (15.3–17.8) | [5,44] | 0.000 | (−0.044, 0.045) | [5,44] | 0.0 | ↔ | −0.12 | 3322 |

| Meropenem (MER) | 0.5 | (0.3–0.8) | [5,41,43,44] | −0.001 | (−0.020, 0.018) | [5,41,43,44] | 0.0 | ↔ | −0.05 | 3280 |

| Temocillin (TEM) | 11.1 | (10.0–12.2) | −0.002 | (−0.086, 0.082) | 0.0 | ↔ | 0.42 | 3044 | ||

| Ertapenem (ERT) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.6) | −0.005 | (−0.025, 0.016) | −0.1 | ↔ | −0.28 | 2992 | ||

| Aztreonam (AZT) | 19.6 | (18.1–21.0) | −0.012 | (−0.077, 0.052) | −0.1 | ↔ | −0.26 | 2925 | ||

| Amoxicillin (AMO) | 72.7 | (71.2–74.2) | −0.017 | (−0.085, 0.051) | −0.2 | ↔ | −0.06 | 3319 | ||

| Amikacin (AMI) | 1.6 | (1.2–2.1) | −0.018 | (−0.041, 0.006) | −0.2 | ↔ | −0.23 | 3044 | ||

| Ceftazidime (CAZ) | 19.3 | (17.9–20.6) | [27,44] | −0.019 | (−0.065, 0.027) | [27] | −0.2 | ↔ | −0.33 | 3323 |

| Cefotaxime (CTX) | 20.3 | (18.9–21.7) | [27,44] | −0.021 | (−0.070, 0.027) | [27] | −0.3 | ↔ | −0.31 | 3201 |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 35.2 | (33.6–36.8) | [44] | −0.035 | (−0.017, 0.037) | −0.4 | ↔ | −0.35 | 3320 | |

| Cefuroxime (CXM) | 24.2 | (22.8–25.7) | −0.080 | (−0.137, −0.024) | −1.0 | ↓ | −0.39 | 3320 | ||

| Tobramycin (TOB) | 22.1 | (20.6–23.6) | −0.099 | (−0.188, -0.010) | −1.2 | ↓ | −0.65 | 2832 | ||

| Colistin (COL) | 4.0 | (3.3–4.8) | −0.208 | (−0.274, −0.141) | −2.5 | ↓ | −0.37 | 2606 | ||

| Antimicrobial | R(%) (95% CI) | References | TM(%) (95% CI) | References | TY(%) | Pearson | Isolates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethoprim (TRI) | 10.1 | (9.8, 10.4) | 0.052 | (0.026, 0.077) | 0.6 | ↓ | 0.10 | 33,525 | ||

| Penicillin (PEN) | 89.4 | (89.1, 89.7) | 0.050 | (0.034, 0.065) | 0.6 | ↓ | 0.19 | 39,901 | ||

| Rifampicin (RIF) | 1.7 | (1.5, 1.8) | [45] | 0.001 | (−0.015, 0.017) | [45] | 0.0 | ↔ | 0.23 | 35,141 |

| Mupirocin (MUP) | 2.5 | (2.3, 2.6) | −0.001 | (−0.020, 0.017) | 0.0 | ↔ | −0.39 | 33,716 | ||

| Gentamicin (GEN) | 4.1 | (3.9, 4.3) | −0.003 | (−0.023, 0.018) | 0.0 | ↔ | −0.16 | 35,255 | ||

| Clindamycin (CLI) | 22.4 | (22.0, 22.8) | −0.016 | (−0.034, 0.001) | −0.2 | ↔ | −0.24 | 39,962 | ||

| Tetracycline (TET) | 9.7 | (9.4, 10.0) | −0.018 | (−0.041, 0.004) | −0.2 | ↔ | 0.15 | 35,429 | ||

| Fusidic acid (FUS) | 14.5 | (14.2, 14.9) | −0.025 | (−0.044, −0.006) | −0.3 | ↓ | 0.04 | 39,918 | ||

| Erythromicin (ERY) | 26.0 | (25.6, 26.5) | −0.032 | (−0.049, −0.015) | −0.4 | ↓ | −0.24 | 39,971 | ||

| Meticillin (MET) | 15.3 | (14.9, 15.7) | [41] | −0.090 | (−0.113, −0.068) | [41] | −1.1 | ↓ | −0.45 | 39,950 |

| Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | 20.1 | (19.7, 20.5) | −0.116 | (−0.156, −0.075) | −1.4 | ↓ | −0.62 | 35,227 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernandez, B.; Herrero-Viñas, P.; Rawson, T.M.; Moore, L.S.P.; Holmes, A.H.; Georgiou, P. Resistance Trend Estimation Using Regression Analysis to Enhance Antimicrobial Surveillance: A Multi-Centre Study in London 2009–2016. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10101267

Hernandez B, Herrero-Viñas P, Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Holmes AH, Georgiou P. Resistance Trend Estimation Using Regression Analysis to Enhance Antimicrobial Surveillance: A Multi-Centre Study in London 2009–2016. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(10):1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10101267

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernandez, Bernard, Pau Herrero-Viñas, Timothy M. Rawson, Luke S. P. Moore, Alison H. Holmes, and Pantelis Georgiou. 2021. "Resistance Trend Estimation Using Regression Analysis to Enhance Antimicrobial Surveillance: A Multi-Centre Study in London 2009–2016" Antibiotics 10, no. 10: 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10101267

APA StyleHernandez, B., Herrero-Viñas, P., Rawson, T. M., Moore, L. S. P., Holmes, A. H., & Georgiou, P. (2021). Resistance Trend Estimation Using Regression Analysis to Enhance Antimicrobial Surveillance: A Multi-Centre Study in London 2009–2016. Antibiotics, 10(10), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10101267