From Evidence to Clinical Guidelines in Antibiotic Treatment in Acute Otitis Media in Children

Abstract

1. Background

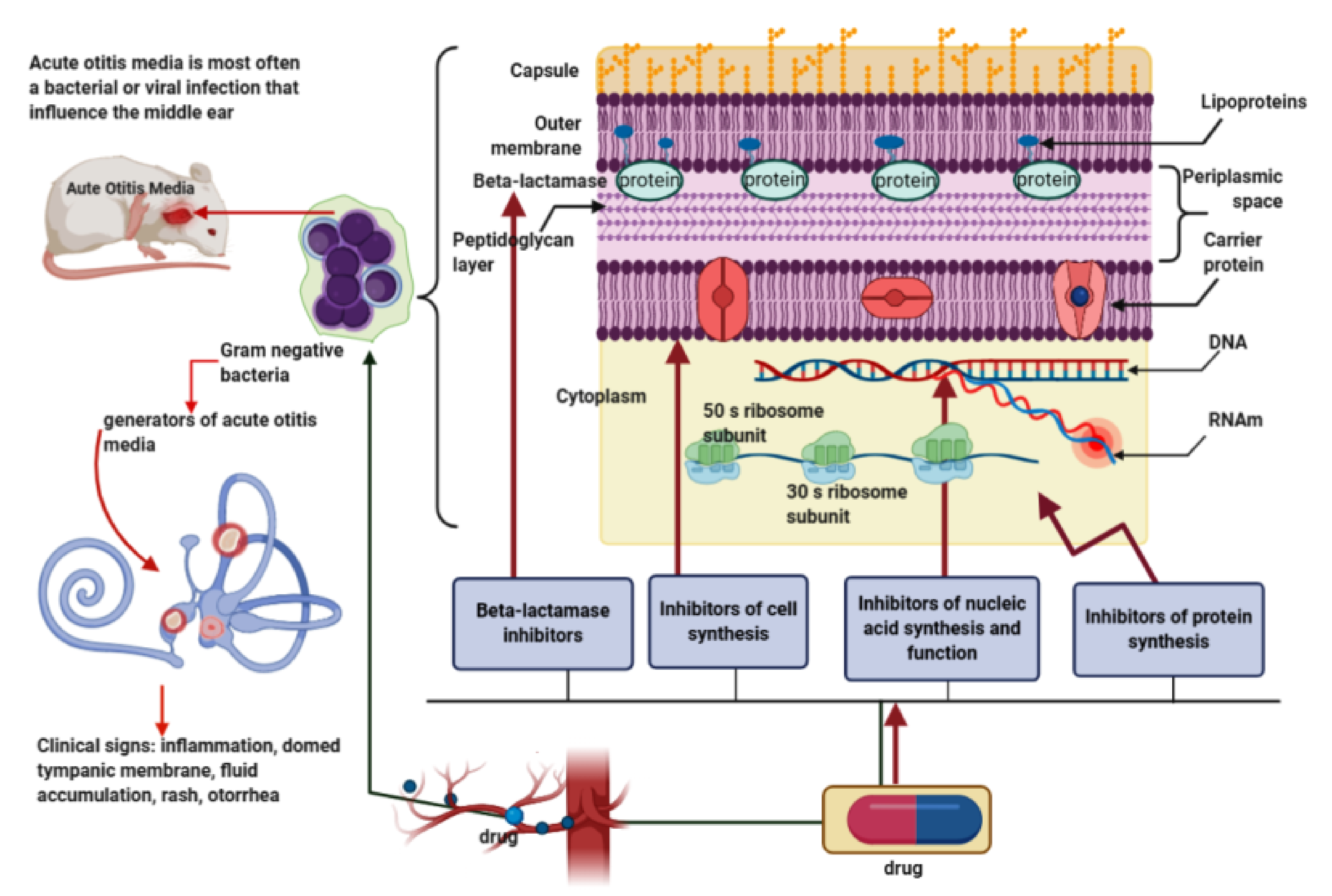

2. Preclinical Evaluation of Antibiotics in Animal Models of Acute Otitis Media

3. Treatment Options, Antibiotic Resistance, and New Antibiotics/Antibiotics’ Schemes in AOM in Children

3.1. Classic Therapeutic Options in AOM in Children

3.2. Antibiotic Resistance

3.3. New Antibiotics/Antibiotic Schemes in the Treatment of AOM in Children

4. Guidelines for Antibiotic Treatment in AOM in Children

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOM | acute otitis media |

| BLPB | bacterial beta-lactamase enzyme |

| IFN-γ | interferon-γ |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | interleukin-8 |

| IM | intramuscularly |

| IV | intravenous |

| MCP1 | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MIC | the minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MIP-2 protein | macrophage inflammatory protein-2 |

| OME; OM | otitis media with effusion; otitis media |

| PBP | penicillin binding proteins |

| PO | per os |

| TGF-β1 | transforming growth factor-β1 |

| TM | trauma severity score |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor- alpha |

| UDP | uridine diphosphate |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Schilder, A.G.M.; Chonmaitree, T.; Cripps, A.W.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Casselbrant, M.L.; Haggard, M.P.; Venekamp, R.P. Otitis media. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.K.; Wong, A.H.C. Acute Otitis Media in Children. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2017, 11, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernacchio, L.; Vezina, R.M.; Mitchell, A.A. Management of acute otitis media by primary care physicians: Trends since the release of the 2004 American Academy of Pediatrics/American Academy of Family Physicians clinical practice guideline. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kurono, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Hotomi, M.; Yano, H.; Watanabe, A.; Matsumoto, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Hanaki, H. The seventh nationwide surveillance of six otorhinolaryngological infectious diseases and the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the isolated pathogens in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Morris, M.; Pichichero, M.E. Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatrics 2017, 140, 20170181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Marchisio, P.; Vergison, A.; Harriague, J.; Hausdorff, W.P.; Haggard, M. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on otitis media: A systematic review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1765–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumarola, F.; Marès, J.; Losada, I.; Minguella, I.; Moraga, F.; Tarragó, D.; Aguilera, U.; Casanovas, J.M.; Gadea, G.; Trías, E.; et al. Microbiology of bacteria causing recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) and AOM treatment failure in young children in Spain: Shifting pathogens in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccination era. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 77, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, D.; McGuirt, W.F. Intracranial complications of acute and chronic infectious ear disease. Laryngoscope 1983, 93, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, R.M.; Kay, D. Natural history of untreated otitis media. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, N.; Hotomi, M.; Billal, D.S. Clinical bacteriology and immunology in acute otitis media in children. J. Infect. Chemother. 2008, 14, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, M.; Bulut, Y.; Sezer, T.; Aladag, I.; Eyibilen, A.; Etikan, I. Bacterial etiology of acute otitis media and clinical efficacy of amoxicillin-clavulanate versus azithromycin. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2006, 70, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, M.; Fukushima, K.; Kamide, Y.; Kunimoto, M.; Matsubara, S.; Sawada, S.; Shintani, T.; Togawa, A.; Uchizono, A.; Uno, Y.; et al. Features predicting treatment failure in pediatric acute otitis media. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 27, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruk, L.A.; Dunkelberger, K.E.; Khampang, P.; Hong, W.; Sadagopan, S.; Alper, C.M.; Fedorchak, M.V. Controlled release of ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone from a single ototopical administration of antibiotic-loaded polymer microspheres and thermoresponsive gel. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhus, Å.; Ryan, A.F. A mouse model for acute otitis media. APMIS 2003, 111, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnaer, E.L.G.M.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Curfs, J.H.A.J. Bacterial otitis media: A new non-invasive rat model. Vaccine 2003, 21, 4539–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Liebeler, C.L.; Quartey, M.K.; Le, C.T.; Giebink, G.S. Middle ear fluid cytokine and inflammatory cell kinetics in the chinchilla otitis media model. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 1943–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardisty, R.E.; Erven, A.; Logan, K.; Morse, S.; Guionaud, S.; Sancho-Oliver, S.; Hunter, A.J.; Brown, S.D.M.; Steel, K.P. The deaf mouse mutant Jeff (Jf) is a single gene model of otitis media. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2003, 4, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Westman, E.; Lundin, S.; Hermansson, A.; Melhus, Å. β-Lactamase-Producing nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae fails to protect Streptococcus pneumoniae from amoxicillin during experimental acute otitis media. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3536–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrer, H.E.; Crompton, M.; Bhutta, M.F. What have we learned from murine models of otitis media? Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013, 13, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, M.S.; Bhutta, M.F.; Cheeseman, M.T.; Burgner, D.; Blackwell, J.M.; Brown, S.D.M.; Jamieson, S.E. Unraveling the genetics of otitis media: From mouse to human and back again. Mamm. Genome 2011, 22, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.C. Direct evidence of bacterial biofilms in otitis media. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 2083–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebda, P.A.; Burckart, G.J.; Alper, C.M.; Diven, W.F.; Doyle, W.J.; Zeevi, A. Upregulation of messenger RNA for inflammatory cytokines in middle ear mucosa in a rat model of acute otitis media. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1998, 107, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piltcher, O.B.; Swarts, J.D.; Magnuson, K.; Alper, C.M.; Doyle, W.J.; Hebda, P.A. A rat model of otitis media with effusion caused by eustachian tube obstruction with and without Streptococcus pneumoniae infection: Methods and course. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002, 126, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Sabharwal, V.; Shlykova, N.; Okonkwo, O.S.; Pelton, S.I.; Kohane, D.S. Treatment of Streptococcus pneumoniae otitis media in a chinchilla model by transtympanic delivery of antibiotics. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e123415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genc, G.; Koyuncu, M.; Kutlar, G.; Guvenc, T.; Gacar, A.; Aksoy, A.; Arslan, S.; Kurnaz, S.C. Does systemic clarithromycin therapy have an inhibitory effect on tympanosclerosis? An experimental animal study. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2015, 129, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, M.F. Mouse models of otitis media: Strengths and limitations. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 147, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, C.J.; Hefeneider, S.H.; Kempton, J.B.; Parrish, S.K.; McCoy, S.L.; Trune, D.R. Evaluation of the mouse model for acute otitis media. Hear. Res. 2006, 219, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebda, P.A.; Piltcher, O.B.; Swarts, J.D.; Alper, C.M.; Zeevi, A.; Doyle, W.J. Cytokine profiles in a rat model of otitis media with effusion caused by eustachian tube obstruction with and without Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Laryngoscope 2002, 112, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Unge, M.; Decraemer, W.F.; Bagger-Sjöbäck, D.; Van Den Berghe, D. Tympanic membrane changes in experimental purulent otitis media. Hear. Res. 1997, 106, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Unge, M.; Decraemer, W.F.; Buytaert, J.A.N.; Dirckx, J.J.J. Evaluation of a model for studies on sequelae after acute otitis media in the Mongolian gerbil. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009, 129, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, C.; Dirckx, J.J.J.; Decraemer, W.F.; Bagger-Sjöbäck, D.; Von Unge, M. Pars flaccida displacement pattern in purulent otitis media in the gerbil. Otol. Neurotol. 2003, 24, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Fernandez, R.; Tsivkovskaia, N.; Harrop-Jones, A.; Hou, H.J.; Dellamary, L.; Dolan, D.F.; Altschuler, R.A.; Lebel, C.; Piu, F. OTO-201: Nonclinical assessment of a sustained-release ciprofloxacin hydrogel for the treatment of otitis media. Otol. Neurotol. 2014, 35, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Chiu, C.H. Clinical manifestations and microbiology of acute otitis media with spontaneous otorrhea in children. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2013, 46, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, T.M.A.; Venekamp, R.P.; Wensing, A.M.J.; Bogaert, D.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Schilder, A.G.M. Acute otorrhea in children with tympanostomy tubes: Prevalence of bacteria and viruses in the post-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minovi, A.; Dazert, S. Erkrankungen des Mittelohres im Kindesalter. Laryngorhinootologie 2014, 93, S1–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, R.M.; Vertrees, J.E.; Carr, J.; Cipolle, R.J.; Uden, D.L.; Giebink, G.S.; Canafax, D.M. Clinical efficacy of antimicrobial drugs for acute otitis media: Metaanalysis of 5400 children from thirty-three randomized trials. J. Pediatr. 1994, 124, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçar, S.; Huseynov, T.; Çoban, M.; Sarıoğlu, S.; Serbetçioğlu, B.; Yalcin, A.D. Montelukast is as effective as penicillin in treatment of acute otitis media: An experimental rat study. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 2013, 19, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Sabharwal, V.; Okonkwo, O.S.; Shlykova, N.; Tong, R.; Lin, L.Y.; Wang, W.; Guo, S.; Rosowski, J.J.; Pelton, S.I.; et al. Treatment of otitis media by transtympanic delivery of antibiotics. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, M.W.; Drinnan, M.; Perry, J.D.; Powell, S.; Wilson, J.A.; Powell, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of antimicrobial resistance in paediatric acute otitis media. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 123, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblüt, A.; Santolaya, M.E.; Gonzalez, P.; Borel, C.; Cofré, J. Penicillin resistance is not extrapolable to amoxicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from middle ear fluid in children with acute otitis media. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2006, 115, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. The role of anaerobic bacteria in chronic suppurative otitis media in children: Implications for medical therapy. Anaerobe 2008, 14, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argaw-Denboba, A.; Abejew, A.A.; Mekonnen, A.G. Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria are Major Threats of Otitis Media in Wollo Area, Northeastern Ethiopia: A Ten-Year Retrospective Analysis. Int. J. Microbiol. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korona-Glowniak, I.; Zychowski, P.; Siwiec, R.; Mazur, E.; Niedzielska, G.; Malm, A. Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in children with acute otitis media- high risk of persistent colonization after treatment. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Asthana, M.; Gupta, A.; Nigam, D.; Mahajan, S. Secondary metabolism and antimicrobial metabolites of penicillium. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering: Penicillium System Properties and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 47–68. ISBN 9780444635013. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.F.; Meroueh, S.O.; Mobashery, S. Bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics: Compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 395–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.M.; da Silva, B.N.M.; Barbosa, G.; Barreiro, E.J. β-Lactam antibiotics: An overview from a medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 208, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks, D.N.F. Pocket Guide to Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 13rd ed.; The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappini, E.; Motisi, M.A.; Becherucci, P.; Pierattelli, M.; Galli, L.; Marchisio, P. Italian primary care paediatricians’ adherence to the 2019 National Guideline for the management of acute otitis media in children: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 138, 110282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Microbiology and Principles of Antimicrobial Therapy for Head and Neck Infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 21, 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, H. Analysis of nasopharyngeal flora in children with acute otitis media attending a day care center. Jpn. J. Antibiot. 2003, 56, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, K.; Iino, Y.; Kamide, Y.; Kudo, F.; Nakayama, T.; Suzuki, K.; Taiji, H.; Takahashi, H.; Yamanaka, N.; Uno, Y. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute otitis media (AOM) in children in Japan—2013 Update. Auris Nasus Larynx 2015, 42, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, R. Good transfer of tebipenem into middle ear effusion conduces to the favorable clinical outcomes of tebipenem pivoxil in pediatric patients with acute otitis media. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Hara, N.; Wajima, T.; Ochiai, S.; Seyama, S.; Shirai, A.; Shibata, M.; Shiro, H.; Natsume, Y.; Noguchi, N. Emergence of Haemophilus influenzae with low susceptibility to quinolones and persistence in tosufloxacin treatment. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 18, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyama, S.; Wajima, T.; Yanagisawa, Y.; Nakaminami, H.; Ushio, M.; Fujii, T.; Noguchi, N. Rise in Haemophilus influenzae with reduced quinolone susceptibility and development of a simple screening method. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 36, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyama, S.; Wajima, T.; Nakaminami, H.; Noguchi, N. Clarithromycin resistance mechanisms of epidemic β-lactamase-nonproducing ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae strains in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3207–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajima, T.; Seyama, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Kashima, C.; Nakaminami, H.; Ushio, M.; Fujii, T.; Noguchi, N. Prevalence of macrolide-non-susceptible isolates among β-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae in a tertiary care hospital in Japan. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2016, 6, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenbach, D.J.; Jones, R.N. Update of cefditoren activity tested against community-acquired pathogens associated with infections of the respiratory tract and skin and skin structures, including recent pharmacodynamic considerations. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 64, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.N.; Pfaller, M.A.; Jacobs, M.R.; Appelbaum, P.C.; Fuchs, P.C. Cefditoren in vitro activity and spectrum: A review of international studies using reference methods. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2001, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodise, T.P.; Kinzig-Schippers, M.; Drusano, G.L.; Loos, U.; Vogel, F.; Bulitta, J.; Hinder, M.; Sörgel, F. Use of population pharmacokinetic modeling and Monte Carlo simulation to describe the pharmacodynamic profile of cefditoren in plasma and epithelial lining fluid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1945–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sevillano, D.; Giménez, M.J.; Alou, L.; Aguilar, L.; Cafini, F.; Torrico, M.; González, N.; Echeverría, O.; Coronel, P.; Prieto, J. Effects of human albumin and serum on the in vitro bactericidal activity of cefditoren against penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seral, C.; Suárez, L.; Rubio-Calvo, C.; Gómez-Lus, R.; Gimeno, M.; Coronel, P.; Durán, E.; Becerril, R.; Oca, M.; Castillo, F.J. In vitro activity of cefditoren and other antimicrobial agents against 288 Streptococcus pneumoniae and 220 Haemophilus influenzae clinical strains isolated in Zaragoza, Spain. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 62, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, Y.; Van Uum, R.T.; De Hoog, M.L.A.; Schilder, A.G.M.; Damoiseaux, R.A.M.J.; Venekamp, R.P. Impact of acute otitis media clinical practice guidelines on antibiotic and analgesic prescriptions: A systematic review. Arch. Dis. Child 2018, 103, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dona, D.; Baraldi, M.; Brigadoi, G.; Lundin, R.; Perilongo, G.; Hamdy, R.F.; Zaoutis, T.; Da Dalt, L.; Giaquinto, C. The Impact of Clinical Pathways on Antibiotic Prescribing for Acute Otitis Media and Pharyngitis in the Emergency Department. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018, 37, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; McCarthy, T.J.; Liberman, D.B. Cost-Effectiveness of watchful waiting in acute Otitis media. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20163086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Recommendations for Management of Common Childhood Conditions: Evidence for Technical Update of Pocket Book Recommendations; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberthal, A.S.; Carroll, A.E.; Chonmaitree, T.; Ganiats, T.G.; Hoberman, A.; Jackson, M.A.; Joffe, M.D.; Miller, D.T.; Rosenfeld, R.M.; Sevilla, X.D.; et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e964–e999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group Recommendations for Clinical Care Guidelines on the Management of Otitis Media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Populations. Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/oatsih-otitis-media-toc~Using-the-Recommendations-for-Clinical-Care-Guidelines-on-Otitis-Media (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Otitis Media (Acute): Antimicrobial Prescribing NICE Guideline; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Marchisio, P.; Bellussi, L.; Di Mauro, G.; Doria, M.; Felisati, G.; Longhi, R.; Novelli, A.; Speciale, A.; Mansi, N.; Principi, N. Acute otitis media: From diagnosis to prevention. Summary of the Italian guideline. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 74, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Castillo Martín, F.; Baquero Artigao, F.; de la Calle Cabrera, T.; López Robles, M.V.; Ruiz-Canela Cáceres, J.; Alfayate Miguélez, S.; Moraga Llop, F.; Cilleruelo Ortega, M.J.; Calvo Rey, C. Consensus document on the aetiology, diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media. Pediatr. Atension Primaria 2012, 14, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansk Selskab for Almen Medicin. Luftvejsinfektioner—DSAM Vejledninger. Respiratory Tract Infections—Diagnosis and Treatment 2014. Available online: https://vejledninger.dsam.dk/luftvejsinfektioner/ (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé. Antibiothérapie par Voie Générale en Pratique Courante—EM Consulte. Recommendations for Good Practice—Antimicrobials by General Route in Current Practice in Upperrespiratory Tract Infections. Available online: https://www.em-consulte.com/article/143366/antibiotherapie-par-voie-generale-en-pratique-cour (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Ralston, S.L.; Lieberthal, A.S.; Meissner, H.C.; Alverson, B.K.; Baley, J.E.; Gadomski, A.M.; Johnson, D.W.; Light, M.J.; Maraqa, N.F.; Mendonca, E.A.; et al. Clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e1474–e1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingery, J.; Taylor, W.; Braun, D. Acute otitis media. Osteopath. Fam. Physician 2016, 8, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allegemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM). DEGAM-Leitlinie Nr 7-Ohrenschmerzen [DEGAM Guideline Number 7—Earache]. Available online: https://www.awmf.org/en/clinical-practice-guidelines/search-for-guidelines.html#result-list (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Health Services Executive and Royal College of Physicians Ireland. Acute Otitis Media. Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/clinical-strategy-and-programmes/paediatrics-acute-otitis-media.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Conseil Scientifique Domaine de la Santé Otite Moyenne Aigue. Acute Otitis Media. Available online: https://conseil-scientifique.public.lu/dam-assets/publications/antibiotherapie/otite-version-longue.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Damoiseaux, R.A.M.J.; Venekamp, R.P.; Eekhof, J.A.H.; Bennebroek Gravenhorst, F.M.; Schoch, A.G.; Burgers, J.S.; Bouma, M.W.J. Otitis Media Acuta Bij Kinderen/NHG-Richtlijnen. Available online: https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/otitis-media-acuta-bij-kinderen (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Karma, P.; Palva, T.; Kouvalainen, K.; Kärjä, J.; Mäkelä, P.H.; Prinssi, V.P.; Ruuskanen, O.; Launiala, K. Finnish Approach to the Treatment of Acute Otitis Media Report of the Finnish Consensus Conference. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1987, 129, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerlinckx, D. L’usage Rationnel des Antibiotiques Chez L’enfant en Ambulatoire; INAMI: Bruxeles, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hryniewicz, W.; Piotr Albrecht, P.; Radzikowski, A. Rekomendacje Postępowania w Pozaszpitalnych Zakażeniach Układu Oddechowego; Narodowy Instytut Leków: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; ISBN 978-83-938000-5-6. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, A. Diagnostik, Behandling och Uppföljning av Akut Mediaotit (AOM)—Bakgrundsdokumentation; Information från Läkemedelsverket: Uppsala, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard, S.; Büttcher, M.; Heininger, U.; Ratnam, S.; Johannes Trück, C.R.; Wagner, N.; Zucol, F.; Berger, C.; Ritz, N. Guidance for Testing and Preventing Infections and Updating Immunisations in Asymptomatic Refugee Children and Adolescents in Switzerland. Pediatrica 2016, 27, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bébrová, E.J.B.; Cizek, H.; Vaclav, D.; Galský, J.; Prakt, L. Doporučený postup pro antibiotickou léčbu komunitních respiračních infekcí v primární péči. Prakt. Lék 2003, 83, 502–515. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buchem, F.L. The treatment of acute otitis media. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 1989, 133, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ovnat Tamir, S.; Shemesh, S.; Oron, Y.; Marom, T. Acute otitis media guidelines in selected developed and developing countries: Uniformity and diversity. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.G.; Dewez, J.E.; Nijman, R.G.; Yeung, S. Clinical practice guidelines for acute otitis media in children: A systematic review and appraisal of European national guidelines. BMJ Open 2020, 10, 35343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MICE [17,19,20,26,27] |

| Advantage: animal small size, low husbandry cost, easy handling; availability of transgenic and knockout strains; a well-defined immune system, genetic tractability and a well-described microbiological status; availability of appropriate reagents. Disadvantage: small size of middle ear and thin tympanic membrane; anesthetic drugs susceptibility; large and patent Eustachian tube. |

| RATS [15,22,23,28] |

| Advantage: the opening Eustachian tube pressure corresponds to that in humans; anatomy and histology of middle ear compatible with that of the human children; medium size tympanic bulla; not susceptible to sepsis; pharmacokinetic profile and gene. Disadvantage: capable of developing spontaneous acute otitis media. |

| CHINCHILLA [24,25] |

| Advantage: large bulla that allows for an easy inoculation of pathogens; tympanic membrane almost the same dimension as in humans; rarely develops natural acute otitis media; anatomy and histology of middle ear compatible with that of the human children; susceptible to humans pathogens of the middle ear. Disadvantage: prone to developing general sepsis accompanied by a high mortality rate. |

| GERBIL [29,30,31] |

| Advantage: a relatively large middle ear; a small incidence of spontaneous acute otitis media; susceptible to humans pathogens of the middle ear; animal small size, low husbandry cost, easy handling. Disadvantage: tight external auditory canal. |

| GUINEA PIG [13,32] |

| Advantage: easy middle ear inoculation of pathogens. Disadvantage: narrow external auditory canal and reduced middle ear volume; differences in the anatomy and histology of middle ear, pharmacokinetic parameters and immune status; difficulty in generating otitis media. |

| Types of Animals and Author | Causative Pathogen and Route of Administration | Antibiotic Therapy | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| RATS | |||

| Piltcher et al. [23]; Hebda et al. [28]; Genc et al. [25]; Ucar et al. [37] | transbullar inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae, type 6A; transbullar inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae, type 6A; middle ear inoculation of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae; transtympanic suspension of type 3 Pneumococci | intramuscular delivery of 100 mg/kg ampicillin twice daily for 5 days; treated twice daily from day 2 to day 7 with 100 mg/kg ampicillin in gavage delivery; a single daily dose of 100 mg/kg clarithromycin in gavage delivery for 5 weeks; intramuscular injection of 160.000 UI/kg/day penicillin G for 5 days | Experimental design induced reproducible pathologic signs similar to those for OME, and Streptococcus pneumoniae was not recovered on or after day 7 suggests that the therapy introduced efficiently sterilized the middle ear cleft; Both effusion cytokine levels (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α and MIP-2) and mucosal cytokine transcripts (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ, TGF-β1, MCP1, IL-8) were much less after antibiotic therapy; The drug decreased the tympanosclerosis severity determined by acute otitis media and myringotomies; Favorable effects on the mucosal changes of the middle ear |

| CHINCHILLA | |||

| Post et al. [21]; Yang et al. [24]; Yang et al. [38] | transbullar inoculation of non-typable Hemophilus influenzae; transnasal inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae; transbullar inoculation of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae | intramuscular ampicillin therapy twice daily for 4 days, 50 mg/kg/per dose; topical delivery of 1 to 4% ciprofloxacin –3CPE-(P407-PBP) hydrogel formulation transtympanic delivery of 2 mg of ciprofloxacin hydrogel formulation | In the samples harvested at 120 h after ampicillin treatment, no obvious bacterial biofilm was observed, even if individual bacteria were again easy to identify. A single transtympanic application of 4% ciprofloxacin-3CPE-[P407-PBP] hydrogel was able to cure Streptococcus pneumoniae. The hydrogel system completely eliminated otitis media in all animals tested, while only 62.5% of chinchillas who received 1% ciprofloxacin alone monotherapy eradicated the infection by day 7. The drug delivery system was biocompatible in the ear and ciprofloxacin was undetectable in the blood, suggesting an adequate local drug distribution and activity |

| GUINEA PIGS | |||

| Bruk et al. [13]; Wang et al. [32] | transbullar injection of non-typeable Haemophilus influenza; middle ear; inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae | a single topical delivery of ciprofloxacin (10 mg) and ceftriaxone (30 mg)-loaded polymer microspheres and thermoresponsive gel; intratympanic injection of various doses of ciprofloxacin hydrogel 0.06% to 12% (containing ciprofloxacin in 16% poloxamer 407 | Ciprofloxacin microspheres/gel therapy resulted in a significant reduced bacterial count on days 7 and 14 post-inoculation, with complete clearance detected on day 14. Ceftriaxone microspheres/gel treatment resulted in an important decreased infection after 7 days of therapy, with a recurrence of infection by day 14. A single intratympanic delivery of ciprofloxacin hydrogel offers an equal therapy effect against OM as a twice daily multiday regimen of Ciprodex (0.3% ciprofloxacin and 0.1% dexamethasone suspension) or Cetraxal (0.2% ciprofloxacin solution) topical drops |

| Country Guideline | Age (Months) | Unilateral AOM | Bilateral AOM in Children | Severe Symptoms | TM Perforation/Otorrhoea | Recurrent AOM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO [65] | All age groups | Yes | Yes * | Yes | Yes | - |

| USA [66] | - | Yes | Yes * | Yes | - | Yes |

| Australia [67] | <24 | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| UK [68] | All age groups # | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | - |

| Italy [69] | - | Yes | Yes * | Yes | Yes | - |

| Spain [70] | <24 | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Denmark [71] | <6 | - | Yes * | Yes | - | Yes |

| France [72] | <24 | - | - | Yes | - | - |

| Portugal [73] | <6 | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Norway [74] | <12 | - | Yes * | - | Yes | - |

| Germany [75] | <24 | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ireland [76] | - | - | - | - | Yes | - |

| Luxembourg [77] | <24 | - | Yes ** | Yes | - | - |

| Netherlands [78] | <6 | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | - |

| Finland [79] | <24 | - | Yes *** | - | Yes | - |

| Belgium [80] | <6 | - | Yes *** | Yes | Yes | - |

| Poland [81] | <6 | Yes | Yes * | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sweden [82] | <12 | - | Yes *** | Yes | Yes | - |

| Switzerland [83] | <24 | - | Yes * | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Czech Republic [84] | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | - |

| Country Guideline | First Line Antibiotic and Duration | Second line/Treatment Failure | Third Line/Allergy to First Line |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO | PO amoxicillin, 80 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses for 7–10 days | Repeat antibiotics for another 5 days | Not specified |

| USA | PO amoxicillin, 80 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses; <2 years of age: 10 days; 2–5 years of age: 7 days; >6 years of age: 5–7 days | Treatment failure: Amoxicillin-clavulanate 90 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | Penicillin allergy: Cefdinir 14mg/kg per day per day/in 2 divided doses, cefuroxime 30 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses, cefpodoxime 10 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses, ceftriaxone 50 mg IM or IV/day for 1–3 days |

| Australia | PO amoxicillin 50 mg/kg in 2 divided doses in AOM without middle ear discharge for 7 days | High doses (e.g., amoxicillin 90 mg/kg) if failure to respond to standard | Not specified |

| PO amoxicillin 50–90 mg/kg in 2 divided doses or in 3 divided doses in AOM with perforation for 14 days | |||

| UK | PO amoxicillin, 1–11 months of age: 125 mg in 3 divided doses 1–4 years: 250 mg in 3 divided doses 5–7 days | Treatment failure: Amoxicillin-clavulanate | Penicillin allergy: Clarithromycin or erythromycin; dosage dependent on age |

| Italy | Mild symptoms and no otorrhea nor risk factors: PO Amoxicillin, 10 days < 2 years of age; 50 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses or in 3 divided doses, 5 days <2 years of age; Severe symptoms, otorrhea, or risk factors for bacterial resistance Amoxicillin-clavulanate 80–90 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses or in 3 divided doses | Treatment failure: If treated with amoxicillin or cefaclor: amoxicillin + clavulanate or cefpodoxime proxetil or cefuroxime axetil. If treated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic: IM or IV ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg per day | Penicillin allergy: macrolide |

| Spain | PO Amoxicillin 80–90 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 5 days | Treatment failure: Amoxicillin-clavulanate 80–90 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 7–10 days, IM/IV Ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses | Penicillin allergy: Cefuroxime axetil 30 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses |

| Denmark | PO Penicillin V, 60 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 7 days | Treatment failure: <2 years of age: Amoxicillin-clavulanate 10/2.5 mg/kg/dose in 3 divided doses for 7 days; 2–12 years of age: amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 1-/2.5 mg/kg/dose 8 h for 7 days | Penicillin allergy: clarithromycin 7.5 mg/kg/dose x 2 for 7 days |

| France | PO amoxicillin 80–90 mg/kg/day in 2–3 divided doses; >2 years of age: 5 days, <2 years of age: 8–10 days | Treatment failure: PO Amoxicillin/clavulanate 80 mg/kg/day and PO amoxicillin 70 mg/kg/day, IM/IV ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg daily for 3 days | Allergy to beta lactams: erythromycin-sulfafurazole or cotrimoxazole. Allergy to penicillin’s without allergy to; cephalosporin’s: cefpodoxime |

| Portugal | Amoxicillin 80–90 mg/day in 2 divided doses; 5 days | Treatment failure: PO/IV Amoxicillin and clavulanate 80–90 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses, PO Cefuroxime-axetil 30 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses, IV 80–100 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses 7 days if <2 years, IM/IV Ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg/day once daily | Penicillin allergy: Clarithromycin 50 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses or Erythromycin 50 mg/kg/day in 3–4 divided doses per day or Azithromycin 10 mg/kg/day once a day |

| Norway | PO phenoxymethylpenicillin 24–60 mg/kg/day in 3–4 divided doses per day for 5 days | Treatment failure: trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole | Allergy: Erythromycin or Clarithromycin (children over 6 months) |

| Germany | PO Amoxicillin 50 mg/kg/day in 2–3 divided doses. If from country with high rates of penicillin resistance: PO amoxicillin 80–90 mg/kg/day for 7 days | Treatment failure: PO amoxicillin 80–90 mg/kg/day; Second choice: PO cephalosporin including cefuroxime axetil (20–30 mg/kg/day for 5 days) | Allergy to penicillin’s/ cephalosporin’s: erythromycin 7 days |

| Ireland | Amoxicillin (no specifications regarding duration, route or frequency) | Not specified | Not specified |

| Luxembourg | Amoxicillin 80–90 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses; <6 years 10 days treatment >6 years 5–7 days treatment | Treatment failure: Amoxicillin/clavulanate; Otherwise cefuroxime axetil, ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg/day for 3 days, azithromycin, Clarithromycin, clindamycin | If vomiting: Ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg once daily for 3 days. Penicillin allergy: Cefuroxime 30 mg/kg in two divided doses |

| Netherlands | Amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses, for 7 days | Second line and also treatment failure: Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 40/10 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 7 days | Penicillin allergy: cotrimoxazole 36 mg/kg/day in two divided doses; 5–7 days |

| Finland | PO Amoxicillin 40 mg/kg/day 8–12 h/PO amoxicillin-clavulanate 40/5.7 mg/kg/day in 2–3 divided doses; 5–7 days | If vomiting: IM Ceftriaxone (one dose) | Penicillin allergy: cefaclor, cefuroximexetil, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, azithromycin or clarithromycin |

| Belgium | PO amoxicillin 75–100 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 7 days | Treatment failure: cefuroxime axetil 30–50 mg/kg in 3 doses amoxicillin-clavulanate 50/37.5 mg/kg in 3 doses | In case of Allergy to cephalosporin’s: co-trimoxazole (Trimethoprim 8 mg/kg/day and Sulfamethoxazole 40 mg/kg/day) in 3 divided doses or Levofloxacin 10 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spoială, E.L.; Stanciu, G.D.; Bild, V.; Ababei, D.C.; Gavrilovici, C. From Evidence to Clinical Guidelines in Antibiotic Treatment in Acute Otitis Media in Children. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10010052

Spoială EL, Stanciu GD, Bild V, Ababei DC, Gavrilovici C. From Evidence to Clinical Guidelines in Antibiotic Treatment in Acute Otitis Media in Children. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10010052

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpoială, Elena Lia, Gabriela Dumitrita Stanciu, Veronica Bild, Daniela Carmen Ababei, and Cristina Gavrilovici. 2021. "From Evidence to Clinical Guidelines in Antibiotic Treatment in Acute Otitis Media in Children" Antibiotics 10, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10010052

APA StyleSpoială, E. L., Stanciu, G. D., Bild, V., Ababei, D. C., & Gavrilovici, C. (2021). From Evidence to Clinical Guidelines in Antibiotic Treatment in Acute Otitis Media in Children. Antibiotics, 10(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10010052