Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Development of Biosensors: A Current Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

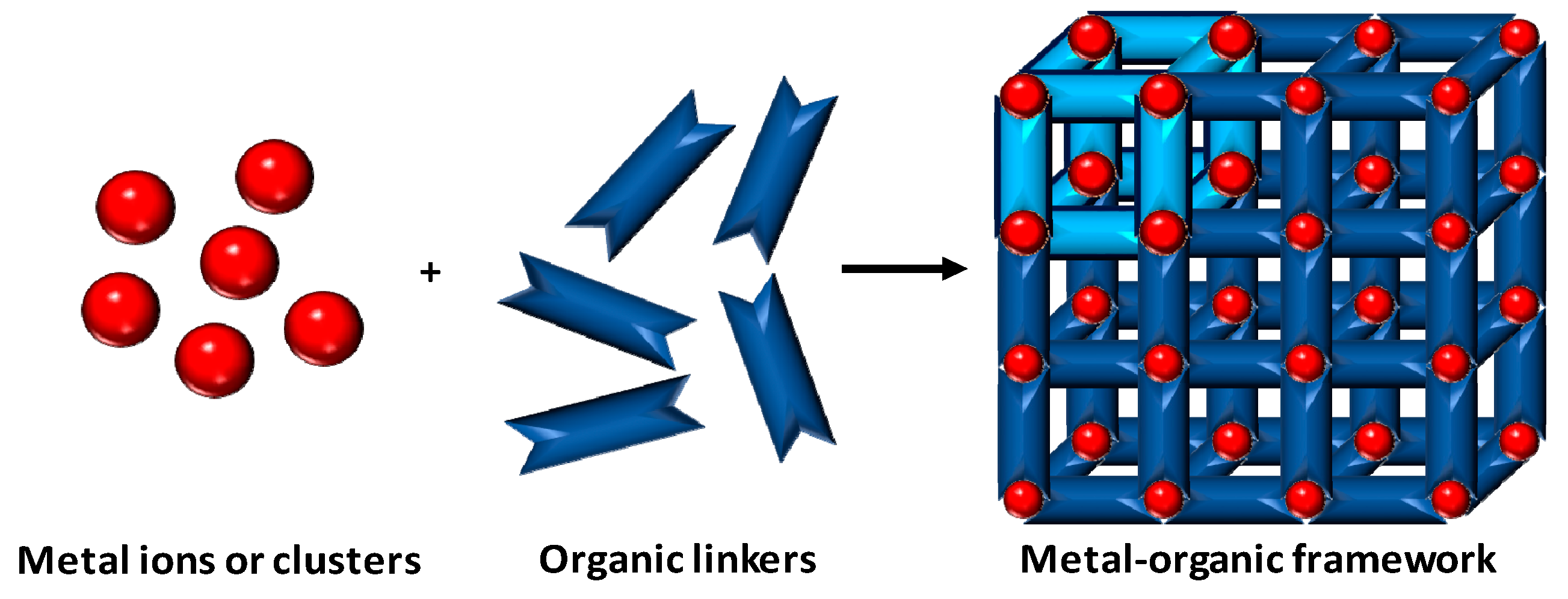

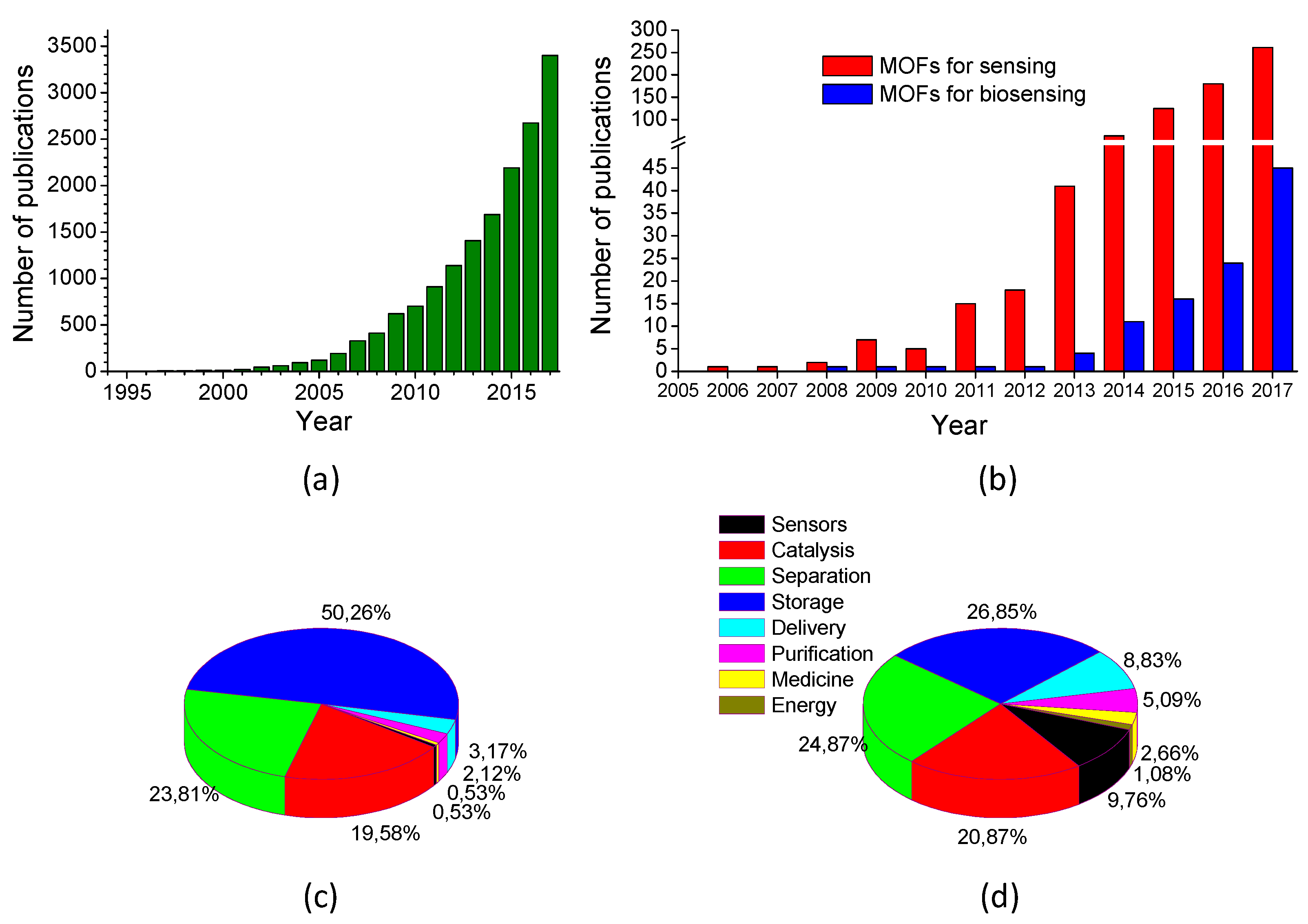

2. Metal-Organic Frameworks

3. State of the Art

4. MOFs for Biosensing

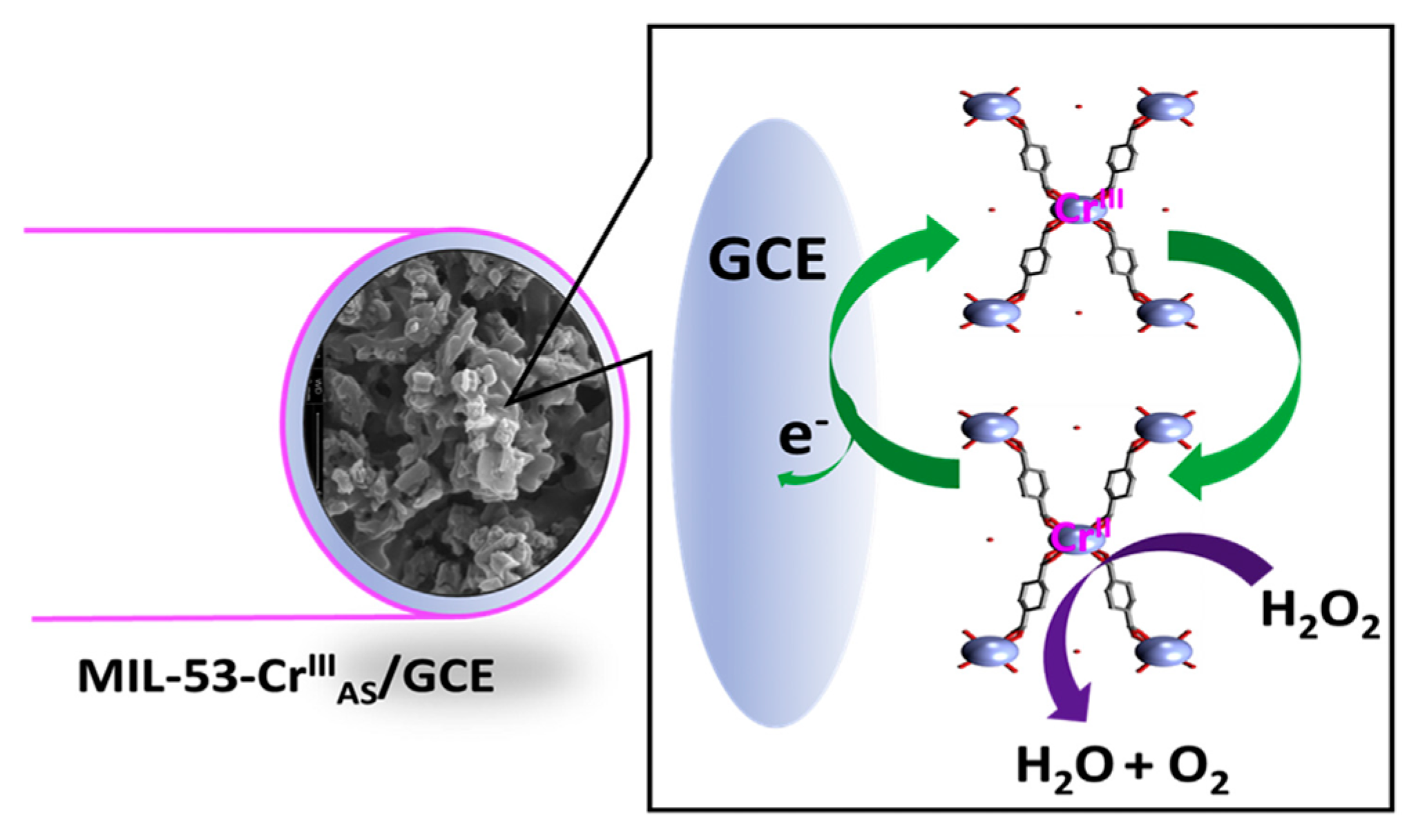

4.1. Raw MOFs

4.2. “Grafting to” Approaches

4.2.1. Bulk MOFs

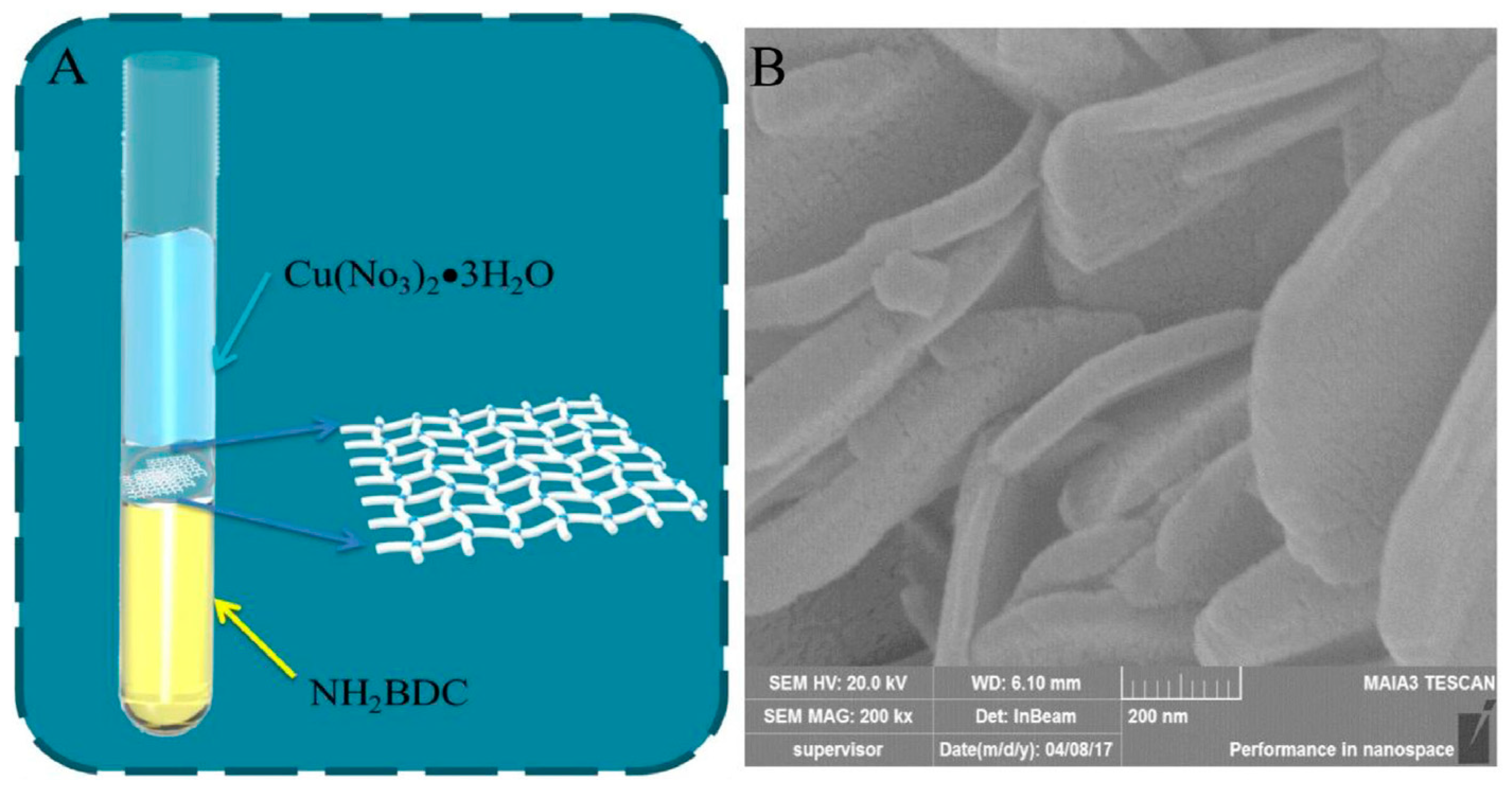

4.2.2. Nanosheets

4.2.3. Metal Nanoparticles @ MOF

4.2.4. Pyrolysis/Calcination

4.3. “Grafting From” Approaches

4.3.1. Metal/Metal Oxide-Based Cores

4.3.2. Carbon-Based Cores

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,10-phen | 1,10-phenantroline |

| 2ATPA | 2-aminoterephtalic acid |

| 2MI | 2-methylimidazole |

| 4bpy | 4,4′-bipyridine |

| 5FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| AA | ascorbic acid |

| Ab | antibody |

| ABTS | 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid |

| AcO | acetate |

| AcOH | acetic acid |

| ADRB1 | adrenergic receptor gene |

| AFP | alpha-fetoprotein |

| AgNPs | silver nanoparticles |

| APTES | (3-aminopropyl)-triethoxysilane |

| AQPDC | amino-quaterphenyldicarboxylic acid |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| AuNPs | gold nanoparticles |

| AuNRs | gold nanorods |

| AuPtNPs | gold and platinum nanoparticles |

| AUR | Amplex UltraRed |

| B4C | 1,2,4,5-benzenetetracarboxylic acid |

| BA | benzoic acid |

| BBDC | 5-boronobenzene-1,3-dicarboxylic acid |

| β-CD | β-cyclodextrin |

| beb | 1,4-bis(2-ethylbenzimidazol-1-ylmethyl) benzene |

| BHB | bovine hemoglobin |

| BTC | trimesic acid |

| BPA | bisphenol A |

| BPDC | 4,4′-biphenyldicarboxylate |

| bpe | 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethylene |

| bpea | 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethane |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| BTC | trimesic acid |

| CAP | chloramphenicol |

| Cbdcp | N-(4-carboxybenzyl)-(3,5-dicarboxyl)pyridinium |

| cDNA | capture DNA |

| CEA | carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CL | chemiluminescence |

| CTAB | cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide |

| CPE | carbon paste electrode |

| DBP(Pt) | Pt-5,15-di(p-benzoato)porphyrin |

| DCA | dipicolinic acid |

| DEF | N,N-diethylformamide |

| DMA | N,N-dimethylacetamide |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| dps | 4,4’-dipyridyl sulfide |

| DPV | differential pulse voltammetry |

| DR | dynamic range |

| dsDNA | double-stranded DNA |

| DTOA | dithiooxamide |

| EC | electrochemical |

| ECL | electrochemiluminescence |

| EIS | electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| Et3N | triethylamine |

| EtOH | ethanol |

| FA | fumaric acid |

| FAM | carboxyfluorescein |

| FGFR3 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 |

| FL | fluorescence |

| FRET | Förster resonance energy transfer |

| FTO | fluorinated tin oxide |

| Gal-3 | galectin-3 |

| g-C3N4 | graphitic carbon nitride |

| GCE | glassy carbon electrode |

| GO | graphene oxide |

| GOP | graphene oxide paper |

| GP | graphene paper |

| H2ada | 1,3-adamantanediacetic acid |

| H2bpdc | 2,2′-bipyridine-6,6′-dicarboxylic acid |

| H2dcbbBr | 1-(3,5-dicarboxybenzyl)-4,4’-bipyridinium bromide |

| H2Leu | N-(2-hydroxybenzyl)-L-leucine |

| H3CmdrpBr | N-carboxymethyl-3,5-dicarboxylpyridinium bromide |

| H3DcbcpBr | N-(3,5-dicarboxylbenzyl)-(3-carboxyl) pyridinium bromide |

| H3NBB | 4′,4′″,4′″″-nitrilotris([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid) |

| H3TAB | 4,4′,4′′-s-triazine-2,4,6-triyl-tribenzoic acid |

| H4TCPB | 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) benzene |

| HA | hippuric acid |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HKUST | Hong Kong University of Science and Technology |

| HSA | human serum albumin |

| HXA | hypoxanthine |

| ITO | indium tin oxide |

| KANA | kanamycin |

| KSC | macroporous carbon |

| LAG-3 | lymphocyte activation gene-3 protein |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LPA | lysophosphatidic acid |

| LSPR | localized surface plasmon resonance |

| MBA | N,N-methylenebisacrylamide |

| MBZ | α-methylbenzylamine |

| MeOH | methanol |

| MIL | materials of Institute Lavoisier |

| MIP | molecularly imprinted polymer |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MOF | metal organic framework |

| MUC1 | mucin 1 |

| N-G | nitrogen-doped graphene sheets |

| N-GNRs | nitrogen-doped graphene nanoribbons |

| NIPAAM | N-isopropyl acrylamide |

| NDC | 1,4-naphtalenedicarboxylic acid |

| NPC | nanoporous carbon |

| OMC | ordered mesoporous carbon |

| OTA | ochratoxin A |

| OTC | oxytetracycline |

| PAA | polyacrylic acid |

| PBA | 3-aminophenylboronic acid hemisulfate |

| PCN | porous coordination network |

| PDA | polydopamine |

| PdNPs | palladium nanoparticles |

| PEC | photoelectrochemical |

| PEDOT NTs | poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) nanotubes |

| PKA | protein kinase A |

| PL | photoluminescence |

| PrOH | propanol |

| PS | polystyrene |

| PSA | prostate specific antigen |

| PVP | polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| QD | quantum dot |

| rGO | reduced graphene oxide |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| ROX | 5(6)-carboxyrhodamine, triethylammonium salt |

| RSD | relative standard deviation |

| [Ru(bpy)3]2+ | tris(bipyridine) ruthenium (II) |

| [Ru(dcbpy)3]2+ | tris(4,4′-dicarboxylicacid-2,2′-bipyridyl) ruthenium(II) |

| sDNA | signal DNA |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SPR | surface plasmon resonance |

| ssDNA | single-stranded DNA |

| TCPP | tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin |

| TDA | 2,2′-thiodiacetic acid |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| TFA | trifluoroacetic acid |

| TIA | 5-triazoleisophtalic acid |

| TiTB | tetrabutyl titanate |

| TMB | 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine |

| TPA | terephtalic acid |

| UCNPs | up-conversion nanoparticles |

| UiO | Universitetet i Oslo |

| UV–vis | ultraviolet–visible |

| ZIF | zeolitic imidazolate framework |

References

- Göpel, W.; Jones, T.A.; Göpel, W.; Zemel, J.N.; Seiyama, T. Historical Remarks. In Sensors: Chemical and Biochemical Sensors; Göpel, W., Hesse, J., Zemel, J.N., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 2, pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, M.J.; Scanaill, C.N. Regulations and Standards: Considerations for Sensor Technologies. In Sensor Technologies: Healthcare, Wellness, and Environmental Applications; McGrath, M.J., Scanaill, C.N., Eds.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, K.W. Environmental Sensors. In Sensors: Micro- and Nanosensor Technology-Trends in Sensor Markets; Meixner, H., Jones, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 8, pp. 451–489. [Google Scholar]

- Scully, P.J.; Quevauviller, P. Optical Techniques for Water Monitoring. In Monitoring of Water Quality: The Contribution of Advanced Technologies; Elsevier, Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Korzeniowska, B.; Nooney, R.; Wencel, D.; McDonagh, C. Silica nanoparticles for cell imaging and intracellular sensing. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 442002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doria, G.; Conde, J.; Veigas, B.; Giestas, L.; Almeida, C.; Assunção, M.; Rosa, J.; Baptista, P.V. Noble Metal Nanoparticles for Biosensing Applications. Sensors 2012, 12, 1657–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Bondi, M.C.; Benito-Peña, E.; Carrasco, S.; Urraca, J.L. Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-based Optical Chemosensors for Selective Chemical Determinations. In Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for Analytical Chemistry Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2018; pp. 227–281. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Tian, G.; Zeng, L.; Song, X.; Bian, X.-W. Nanoscaled Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biosensing, Imaging, and Cancer Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1800022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martynenko, I.V.; Litvin, A.P.; Purcell-Milton, F.; Baranov, A.V.; Fedorov, A.V.; Gun’ko, Y.K. Application of semiconductor quantum dots in bioimaging and biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 6701–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Campuzano, S.; Pingarrón, M.J. Fullerenes in Electrochemical Catalytic and Affinity Biosensing: A Review. C 2017, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Min, D.-H. Biosensors based on graphene oxide and its biomedical application. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Chen, X.; Ren, T.; Zhang, P.; Yang, D. Carbon nanotube based biosensors. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2015, 207, 690–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, F.; Turner, A.P.F. New Micro- and Nanotechnologies for Electrochemical Biosensor Development. Biosensor Nanomaterials, Li, S., Singh, J., Li, H., Banerjee, I.A., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Batten, S.R.; Champness, N.R.; Chen, X.-M.; Garcia-Martinez, J.; Kitagawa, S.; Öhrström, L.; O’Keeffe, M.; Paik Suh, M.; Reedijk, J. Terminology of metal-organic frameworks and coordination polymers. Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtch, N.C.; Jasuja, H.; Walton, K.S. Water Stability and Adsorption in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10575–10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucier, B.E.G.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y. Characterization of Metal-Organic Frameworks: Unlocking the Potential of Solid-State NMR. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howarth, A.J.; Peters, A.W.; Vermeulen, N.A.; Wang, T.C.; Hupp, J.T.; Farha, O.K. Best Practices for the Synthesis, Activation, and Characterization of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Feng, L.; Wang, K.; Pang, J.; Bosch, M.; Lollar, C.; Sun, Y.; Qin, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, P. Stable Metal-Organic Frameworks: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Dinca, M. Reductive Electrosynthesis of Crystalline Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12926–12929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kutubi, H.; Gascon, J.; Sudhölter, E.J.R.; Rassaei, L. Electrosynthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks: Challenges and Opportunities. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.-L.; Xu, Q. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Platforms for Catalytic Applications. Adv. Mater. 2017, 30, 1703663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.-S.; Bu, X.; Feng, P. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Separation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.-Y.; Yang, C.-X.; Chang, N.; Yan, X.-P. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Analytical Chemistry: From Sample Collection to Chromatographic Separation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-X.; Yang, Y.-W. Metal-Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Drug/Cargo Delivery and Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Lollar, C.T.; Li, J.; Zhou, H.-C. Recent advances in gas storage and separation using metal-organic frameworks. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Zou, R.; Xu, Q. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Energy Applications. Chem 2017, 2, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Teat, S.J.; Olson, D.H.; Li, J. Synthesis, Structure, and Selective Gas Adsorption of a Single-Crystalline Zirconium Based Microporous Metal-Organic Framework. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 2034–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre-Requena, J.V.; Marqués-López, E.; Herrera, R.P.; Díaz, D.D. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) bring new life to hydrogen-bonding organocatalysts in confined spaces. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 3985–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Samanta, P.; Desai, A.V.; Ghosh, S.K. Guest-Responsive Metal-Organic Frameworks as Scaffolds for Separation and Sensing Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2457–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küsgens, P.; Rose, M.; Senkovska, I.; Fröde, H.; Henschel, A.; Siegle, S.; Kaskel, S. Characterization of metal-organic frameworks by water adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 120, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ye, J.-W.; Wang, H.-P.; Pan, M.; Yin, S.-Y.; Wei, Z.-W.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Wu, K.; Fan, Y.-N.; Su, C.-Y. Ultrafast water sensing and thermal imaging by a metal-organic framework with switchable luminescence. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickey, F.H. The Preparation of Specific Adsorbents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1949, 35, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghi, O.M.; Richardson, D.A.; Li, G.; Davis, C.E.; Groy, T.L. Open-Framework Solids with Diamond-Like Structures Prepared from Clusters and Metal-Organic Building Blocks. MRS Symp Proc. 2011, 371, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Bondi, M.C.; Urraca, J.L.; Carrasco, S.; Navarro-Villoslada, F. Preparation of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers. In Handbook of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers; Álvarez-Lorenzo, C., Concheiro, Á., Eds.; Smithers Rapra Technology Ltd.: Akron, OH, USA, 2013; pp. 23–86. [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay, A.C.; Morris, R.E.; Horcajada, P.; Férey, G.; Gref, R.; Couvreur, P.; Serre, C. BioMOFs: Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biological and Medical Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6260–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreno, L.E.; Leong, K.; Farha, O.K.; Allendorf, M.; Van Duyne, R.P.; Hupp, J.T. Metal-Organic Framework Materials as Chemical Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1105–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, K.; Wong-Foy, A.G.; Matzger, A.J. MOF@MOF: Microporous core–shell architectures. Chem. Commun. 2009, 6162–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.; Jeong, H.-K. Heteroepitaxial Growth of Isoreticular Metal−Organic Frameworks and Their Hybrid Films. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Ni, Z.; Côté, A.P.; Choi, J.Y.; Huang, R.; Uribe-Romo, F.J.; Chae, H.K.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10186–10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingleson, M.J.; Perez Barrio, J.; Guilbaud, J.-B.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Rosseinsky, M.J. Framework functionalisation triggers metal complex binding. Chem. Commun. 2008, 2680–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, R.K.; Minnaar, J.L.; Telfer, S.G. Thermolabile Groups in Metal-Organic Frameworks: Suppression of Network Interpenetration, Post-Synthetic Cavity Expansion, and Protection of Reactive Functional Groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4598–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.-J.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z.-H.; Liu, T.-F.; Lü, J.; Gao, S.-Y.; He, C.; Cao, R.; Luo, J.-H. Integration of metal-organic frameworks into an electrochemical dielectric thin film for electronic applications. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Tan, C.; Sindoro, M.; Zhang, H. Hybrid micro-/nano-structures derived from metal-organic frameworks: Preparation and applications in energy storage and conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2660–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendon, C.H.; Rieth, A.J.; Korzyński, M.D.; Dincă, M. Grand Challenges and Future Opportunities for Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, H.D.; Rafiq, K.; Yoo, H. Nano Metal-Organic Framework-Derived Inorganic Hybrid Nanomaterials: Synthetic Strategies and Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 23, 5631–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lin, X.; Zhao, Y.S.; Yan, D. Recent Advances in Micro-/Nanostructured Metal-Organic Frameworks towards Photonic and Electronic Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6484–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Jin, C.-M.; Shao, T.; Li, Y.-Z.; Zhang, K.-L.; Zhang, H.-T.; You, X.-Z. Syntheses, structures, and luminescence properties of a new family of three-dimensional open-framework lanthanide coordination polymers. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2002, 5, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefa, T.; Shi, Y.-L. Corrugated and nanoporous silica microspheres: Synthesis by controlled etching, and improving their chemical adsorption and application in biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 5604–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, A.; Stylianou, K.C. Electronic metal-organic framework sensors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Gao, C.; Chen, L.; He, Y.; Ma, W.; Lin, Z. Recent advances in biomolecule immobilization based on self-assembly: Organic–inorganic hybrid nanoflowers and metal-organic frameworks as novel substrates. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 1581–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, M. The Applications of Metal−Organic Frameworks in Electrochemical Sensors. ChemElectroChem 2017, 5, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempahanumakkagari, S.; Kumar, V.; Samaddar, P.; Kumar, P.; Ramakrishnappa, T.; Kim, K.-H. Biomolecule-embedded metal-organic frameworks as an innovative sensing platform. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, F.-Y.; Chen, D.; Wu, M.-K.; Han, L.; Jiang, H.-L. Chemical Sensors Based on Metal-Organic Frameworks. ChemPlusChem 2016, 81, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Deep, A.; Kim, K.-H. Metal organic frameworks for sensing applications. Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 73, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.M.; Dincă, M. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Active Materials in Electronic Sensor Devices. Sensors 2017, 17, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-S. Metal-organic frameworks for biosensing and bioimaging applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 349, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Day, G.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhou, H.-C. Luminescent sensors based on metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 354, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.E.; Teplensky, M.H.; Moghadam, P.Z.; Fairen-Jimenez, D. Metal-organic frameworks as biosensors for luminescence-based detection and imaging. Interface Focus 2016, 6, 20160027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Qi, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Gunasekaran, S.; Wang, Q. Sensitive detection of pesticides by a highly luminescent metal-organic framework. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 260, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valekar, A.H.; Batule, B.S.; Kim, M.I.; Cho, K.-H.; Hong, D.-Y.; Lee, U.H.; Chang, J.-S.; Park, H.G.; Hwang, Y.K. Novel amine-functionalized iron trimesates with enhanced peroxidase-like activity and their applications for the fluorescent assay of choline and acetylcholine. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.-P.; Qiu, G.-H.; Hu, P.-P.; Liang, Z.; Liang, Y.-M.; Sun, B.; Bai, L.-P.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Chen, J.-X. Simultaneous detection of Dengue and Zika virus RNA sequences with a three-dimensional Cu-based zwitterionic metal-organic framework, comparison of single and synchronous fluorescence analysis. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 254, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.-H.; Lu, W.-Z.; Hu, P.-P.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Bai, L.-P.; Wang, T.-R.; Li, M.-M.; Chen, J.-X. A metal-organic framework based PCR-free biosensor for the detection of gastric cancer associated microRNAs. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2017, 177, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, H.; Wang, N.; Li, H.; Shen, D.; Ma, H. Duplex voltammetric immunoassay for the cancer biomarkers carcinoembryonic antigen and alpha-fetoprotein by using metal-organic framework probes and a glassy carbon electrode modified with thiolated polyaniline nanofibers. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 4037–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Mehta, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Deep, A. MOF–Bacteriophage Biosensor for Highly Sensitive and Specific Detection of Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 33589–33598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; You, X.; Shi, X. Enhanced Chemiluminescence Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide in Milk Sample Using Metal-Organic Framework Fe–MIL–88NH2 as Peroxidase Mimetic. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-L.; Chen, J.-H.; Ding, L.; Xu, Z.; Wen, L.; Wang, L.-B.; Cheng, Y.-H. Study of the detection of bisphenol A based on a nano-sized metal-organic framework crystal and an aptamer. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 906–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Bansal, V.; Paul, A.K.; Deep, A. Practical utilization of nanocrystal metal organic framework biosensor for parathion specific recognition. Microchem. J. 2016, 128, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-Q.; Qiu, G.-H.; Liang, Z.; Li, M.-M.; Sun, B.; Qin, L.; Yang, S.-P.; Chen, W.-H.; Chen, J.-X. A zinc(II)-based two-dimensional MOF for sensitive and selective sensing of HIV-1 ds-DNA sequences. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 922, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Duan, X.; Lu, K.; Micheroni, D.; Hu, A.; Lin, W. Nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks for Ratiometric Oxygen Sensing in Live Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2158–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, S.N.; Meng, X.; Song, X.Z.; Feng, J.; Song, S.Y.; Zhang, H.J. A Metal-Organic Framework/DNA Hybrid System as a Novel Fluorescent Biosensor for Mercury(II) Ion Detection. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Lin, L.-X.; Fang, Z.-P.; Yang, S.-P.; Qiu, G.-H.; Chen, J.-X.; Chen, W.-H. A water-stable metal-organic framework of a zwitterionic carboxylate with dysprosium: A sensing platform for Ebolavirus RNA sequences. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.-Q.; Yang, S.-P.; Ding, N.-N.; Qin, L.; Qiu, G.-H.; Chen, J.-X.; Zhang, W.-H.; Chen, W.-H.; Hor, T.S.A. A zwitterionic 1D/2D polymer co-crystal and its polymorphic sub-components: A highly selective sensing platform for HIV ds-DNA sequences. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 5092–5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Gao, C.; Xiao, Q.; Lin, G.; Lin, Z.; Cai, Z.; Yang, H. Protein-Metal Organic Framework Hybrid Composites with Intrinsic Peroxidase-like Activity as a Colorimetric Biosensing Platform. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 29052–29061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zheng, H.; Wei, X.; Lin, Z.; Guo, L.; Qiu, B.; Chen, G. Metal-organic framework (MOF): A novel sensing platform for biomolecules. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1276–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-P.; Chen, S.-R.; Liu, S.-W.; Tang, X.-Y.; Qin, L.; Qiu, G.-H.; Chen, J.-X.; Chen, W.-H. Platforms Formed from a Three-Dimensional Cu-Based Zwitterionic Metal-Organic Framework and Probe ss-DNA: Selective Fluorescent Biosensors for Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 ds-DNA and Sudan Virus RNA Sequences. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 12206–12214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.M.; Leng, F.; Zhao, X.J.; Hu, X.L.; Li, Y.F. Metal-organic framework MIL-101 as a low background signal platform for label-free DNA detection. Analyst 2014, 139, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.-N.; Wu, L.-L.; Feng, J.; Song, S.-Y.; Zhang, H.-J. An ideal detector composed of a 3D Gd-based coordination polymer for DNA and Hg2+ ion. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Bao, W.-J.; Ren, S.-B.; Chen, M.; Wang, K.; Xia, X.-H. Fluorescent Sulfur-Tagged Europium(III) Coordination Polymers for Monitoring Reactive Oxygen Species. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 6828–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Ren, C.; Chen, H.; Chen, X. A sensitive biosensor for dopamine determination based on the unique catalytic chemiluminescence of metal-organic framework HKUST-1. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2015, 210, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.-N.; Yan, B. Recyclable lanthanide-functionalized MOF hybrids to determine hippuric acid in urine as a biological index of toluene exposure. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14509–14512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Shi, W.; Cheng, P.; Zaworotko, M.J. A Mixed-Crystal Lanthanide Zeolite-like Metal-Organic Framework as a Fluorescent Indicator for Lysophosphatidic Acid, a Cancer Biomarker. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12203–12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, H.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y. Rapid and facile ratiometric detection of an anthrax biomarker by regulating energy transfer process in bio-metal-organic framework. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 85, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopa, N.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Ahmed, F.; Chandra Sutradhar, S.; Ryu, T.; Kim, W. A base-stable metal-organic framework for sensitive and non-enzymatic electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 274, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Yang, B.; Liu, Z.; Xia, P.; Wang, Q. Target-catalyzed hairpin assembly and metal-organic frameworks mediated nonenzymatic co-reaction for multiple signal amplification detection of miR-122 in human serum. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 102, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Yu, C.; Niu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, R.; He, J. Target triggered cleavage effect of DNAzyme: Relying on Pd-Pt alloys functionalized Fe-MOFs for amplified detection of Pb2+. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 101, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, Y.; Wang, H.; Lan, F.; Liang, L.; Ren, N.; Liu, H.; Ge, S.; Yu, J. Electrochemiluminescence based detection of microRNA by applying an amplification strategy and Hg(II)-triggered disassembly of a metal organic frameworks functionalized with ruthenium(II)tris(bipyridine). Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; He, Z.; Guo, D.; Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Yung, B.; Lin, L.; Yu, G.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, Y. “Three-in-one” Nanohybrids as Synergistic Nanoquenchers to Enhance No-Wash Fluorescence Biosensors for Ratiometric Detection of Cancer Biomarkers. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3461–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, Z.; Wang, F.; Cai, J.; Guo, L.; Su, J.; Liu, Y. Highly sensitive photoelectrochemical biosensor for kinase activity detection and inhibition based on the surface defect recognition and multiple signal amplification of metal-organic frameworks. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 97, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.; Lü, W.; Zuo, X.; Zhu, Q.; Pan, C.; Niu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, X. A novel biosensor based on boronic acid functionalized metal-organic frameworks for the determination of hydrogen peroxide released from living cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 95, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhuo, Y.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y. A novel metal-organic framework loaded with abundant N-(aminobutyl)-N-(ethylisoluminol) as a high-efficiency electrochemiluminescence indicator for sensitive detection of mucin1 on cancer cells. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 9705–9708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, S. Label-free Electrochemical Detection of ATP Based on Amino-functionalized Metal-organic Framework. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Li, G.; Hu, Y. Aptamer-involved fluorescence amplification strategy facilitated by directional enzymatic hydrolysis for bioassays based on a metal-organic framework platform: Highly selective and sensitive determination of thrombin and oxytetracycline. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 2365–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X. Encapsulation of enzyme into mesoporous cages of metal-organic frameworks for the development of highly stable electrochemical biosensors. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 3213–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jia, G.; Li, Z.; Yuan, C.; Bai, Y.; Fu, D. Selective Electrochemical Detection of Dopamine on Polyoxometalate-Based Metal-Organic Framework and Its Composite with Reduced Graphene Oxide. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1601241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Qiu, H. Facile synthesis of enzyme functional metal-organic framework for colorimetric detecting H2O2 and ascorbic acid. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2017, 28, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Li, X.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Liu, P.; Cai, W.; Zhang, C. A simple modified electrode based on MIL-53(Fe) for the highly sensitive detection of hydrogen peroxide and nitrite. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 2082–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gan, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, Q.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y. A novel aptamer-metal ions-nanoscale MOF based electrochemical biocodes for multiple antibiotics detection and signal amplification. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 2017, 242, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Xu, S.; Dai, L.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, L. An enhanced sensitivity towards H2O2 reduction based on a novel Cu metal-organic framework and acetylene black modified electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 230, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Zhu, S.; Yan, M.; Ge, S.; Yu, J. 3D origami electrochemical device for sensitive Pb2+ testing based on DNA functionalized iron-porphyrinic metal-organic framework. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, M.; Dong, S.; Wang, K.; Suo, G. A Porphyrin MOF and Ionic Liquid Biocompatible Matrix for the Direct Electrochemistry and Electrocatalysis of Cytochrome c. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, B200–B204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R.; Zheng, L.; Chi, Y.; Shi, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C. Highly efficient electrochemical recognition and quantification of amine enantiomers based on a guest-free homochiral MOF. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 11701–11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Guo, Z. Ruthenium-based metal organic framework (Ru-MOF)-derived novel Faraday-cage electrochemiluminescence biosensor for ultrasensitive detection of miRNA-141. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 2018, 268, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Y.-X.; Zhang, K.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, D.; Hu, F.; Gan, N. A two dimensional metal-organic framework nanosheets-based fluorescence resonance energy transfer aptasensor with circular strand-replacement DNA polymerization target-triggered amplification strategy for homogenous detection of antibiotics. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Yan, J.; Huang, X.; Guo, L.; Lin, Z.; Luo, F.; Qiu, B.; Wong, K.-Y.; Chen, G. A sensing platform for hypoxanthine detection based on amino-functionalized metal organic framework nanosheet with peroxidase mimic and fluorescence properties. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 267, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; Pang, H.; Hu, X. Ni and NiO Nanoparticles Decorated Metal-Organic Framework Nanosheets: Facile Synthesis and High-Performance Nonenzymatic Glucose Detection in Human Serum. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 22342–22349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linghao, H.; Fenghe, D.; Yingpan, S.; Chuanpan, G.; Hui, Z.; Jia-Yue, T.; Zhihong, Z.; Chun-Sen, L.; Xiaojing, Z.; Peiyuan, W. 2D zirconium-based metal-organic framework nanosheets for highly sensitive detection of mucin 1: Consistency between electrochemical and surface plasmon resonance methods. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 025098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Wen, Y.; Dai, L.; He, Z.; Wang, L. A novel electrochemical sensor for glucose detection based on Ag@ZIF-67 nanocomposite. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 260, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, C. A sensitive sandwich-type immunosensor for the detection of galectin-3 based on N-GNRs-Fe-MOFs@AuNPs nanocomposites and a novel AuPt-methylene blue nanorod. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 101, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Su, F.; Song, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, M.; He, L.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Z. Aptamer-Templated Silver Nanoclusters Embedded in Zirconium Metal-Organic Framework for Bifunctional Electrochemical and SPR Aptasensors toward Carcinoembryonic Antigen. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41188–41199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Qin, Z.; Hao, Y.; He, Q.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, D.; Wen, H.; Chen, J.; Qiu, J. A signal-decreased electrochemical immunosensor for the sensitive detection of LAG-3 protein based on a hollow nanobox-MOFs/AuPt alloy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 113, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.; Wang, L.; Mao, D.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J. Voltammetric hybridization assay for the β1-adrenergic receptor gene (ADRB1), a marker for hypertension, by using a metal organic framework (Fe-MIL-88NH2) with immobilized copper(II) ions. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 3121–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; He, J. A novel non-invasive detection method for the FGFR3 gene mutation in maternal plasma for a fetal achondroplasia diagnosis based on signal amplification by hemin-MOFs/PtNPs. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Li, X.; Yan, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Du, B.; Wei, Q. Sensitive Insulin Detection based on Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer between Ru(bpy)32+ and Au Nanoparticle-Doped β-Cyclodextrin-Pb (II) Metal-Organic Framework. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 10121–10127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jian, Y.; Kong, Q.; Liu, H.; Lan, F.; Liang, L.; Ge, S.; Yu, J. Ultrasensitive electrochemical paper-based biosensor for microRNA via strand displacement reaction and metal-organic frameworks. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 257, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; Shu, Y.; Hu, X. Synthesis of a novel Au nanoparticles decorated Ni-MOF/Ni/NiO nanocomposite and electrocatalytic performance for the detection of glucose in human serum. Talanta 2018, 184, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Peng, L.; Wei, W.; Huang, T. Three MOF-Templated Carbon Nanocomposites for Potential Platforms of Enzyme Immobilization with Improved Electrochemical Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 14665–14672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldorai, Y.; Choe, S.R.; Huh, Y.S.; Han, Y.-K. Metal-organic framework derived nanoporous carbon/Co3O4 composite electrode as a sensing platform for the determination of glucose and high-performance supercapacitor. Carbon 2018, 127, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yan, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J. Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbon-ZnO Nanopolyhedra Derived from ZIF-8: New Materials for Photoelectrochemical Biosensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 42482–42491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Z.; Jiao, K.; Peng, R.; Hu, Z.; Jiao, S. Al-Based porous coordination polymer derived nanoporous carbon for immobilization of glucose oxidase and its application in glucose/O2 biofuel cell and biosensor. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 11872–11879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Tang, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Gao, J.; Wu, S. Magnetic porous carbon nanocomposites derived from metal-organic frameworks as a sensing platform for DNA fluorescent detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 940, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Yang, Q.; Hu, N.; Suo, Y.; Wang, J. Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric detection of glutathione via enhanced Fenton-like reaction of magnetic metal organic framework. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 2018, 262, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ouyang, W.; Guo, L.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, X.; Qiu, B.; Chen, G. Facile synthesis of Fe3O4/g-C3N4/HKUST-1 composites as a novel biosensor platform for ochratoxin A. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, F.; Liu, M.; Li, X. Preparation of graphene nano-sheet bonded PDA/MOF microcapsules with immobilized glucose oxidase as a mimetic multi-enzyme system for electrochemical sensing of glucose. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3695–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Dang, F. Size-selective QD@MOF core-shell nanocomposites for the highly sensitive monitoring of oxidase activities. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Deng, Q.; Fang, G.; Gu, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S. Upconversion fluorescence metal-organic frameworks thermo-sensitive imprinted polymer for enrichment and sensing protein. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hang, L.; Zhou, F.; Men, D.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Cai, W.; Li, C.; Li, Y. Functionalized periodic Au@MOFs nanoparticle arrays as biosensors for dual-channel detection through the complementary effect of SPR and diffraction peaks. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 2257–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.-W.; Kuang, Q.; Zhou, J.-Z.; Kong, X.-J.; Xie, Z.-X.; Zheng, L.-S. Semiconductor@Metal-Organic Framework Core–Shell Heterostructures: A Case of ZnO@ZIF-8 Nanorods with Selective Photoelectrochemical Response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, J.; Hu, R.; Tadepalli, S.; Morrissey, J.J.; Kharasch, E.D.; Singamaneni, S. Amplification of Refractometric Biosensor Response through Biomineralization of Metal-Organic Framework Nanocrystals. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2017, 2, 1700023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Gong, A.; Zhou, H. Visible-light-activated photoelectrochemical biosensor for the detection of the pesticide acetochlor in vegetables and fruit based on its inhibition of glucose oxidase. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 17489–17496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, M.; Gong, C.; Shen, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L. Ratiometric electrochemical glucose biosensor based on GOD/AuNPs/Cu-BTC MOFs/macroporous carbon integrated electrode. Sen. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 257, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bo, X.; Yang, J.; Yin, D.; Guo, L. One-step synthesis of porphyrinic iron-based metal-organic framework/ordered mesoporous carbon for electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide in living cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 248, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Hou, M.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Ge, J. Immobilization on Metal-Organic Framework Engenders High Sensitivity for Enzymatic Electrochemical Detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 13831–13836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gui, M.; Asif, M.; Yu, Y.; Dong, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Xiao, F.; Liu, H. A facile modular approach to the 2D oriented assembly MOF electrode for non-enzymatic sweat biosensors. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 6629–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, M.; Zhao, H.; Feng, Y.; Ge, J. Synthesis of patterned enzyme–metal-organic framework composites by ink-jet printing. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Shen, Y.; Chen, J.; Song, Y.; Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, L. Microperoxidase-11@PCN-333 (Al)/three-dimensional macroporous carbon electrode for sensing hydrogen peroxide. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2017, 239, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Gao, F.; Ni, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z. Graphene Oxide Directed One-Step Synthesis of Flowerlike Graphene@HKUST-1 for Enzyme-Free Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide in Biological Samples. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 32477–32487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.; Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Song, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, L. Microperoxidase-11/metal-organic framework/macroporous carbon for detecting hydrogen peroxide. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 79798–79804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.Y.; Kung, C.W.; Liao, Y.T.; Kao, S.Y.; Cheng, M.; Chang, T.H.; Henzie, J.; Alamri, H.R.; Alothman, Z.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; et al. Enhanced Charge Collection in MOF-525–PEDOT Nanotube Composites Enable Highly Sensitive Biosensing. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrokhian, S.; Khaki Sanati, E.; Hosseini, H. Direct growth of metal-organic frameworks thin film arrays on glassy carbon electrode based on rapid conversion step mediated by copper clusters and hydroxide nanotubes for fabrication of a high performance non-enzymatic glucose sensing platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 112, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Wang, J.; Nie, Y.; Ren, L.; Liu, B.; Liu, G. Metal-Organic Frameworks/Graphene Oxide Composite: A New Enzymatic Immobilization Carrier for Hydrogen Peroxide Biosensors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, B32–B37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(NO3)2/H4TCPB/DMF | FL | Parathion-methyl | 1 μg/kg–10 mg/kg | 0.12 μg/kg | Water | [59] |

| Fe/BTC/H2O/HF,HNO3 | FL | Choline | 0.5–10 μM | 0.027 μM | Milk | [60] |

| Acetylcholine | 0.1–10 μM | 0.036 μM | Serum | |||

| CuSO4/bpe,H3DcbcpBr/H2O | FL | Dengue virus | 1–60 nM | 332 ppm | [61] | |

| Zika virus | 0.5–70 nM | 192 ppm | ||||

| Cu(NO3)2/H2dcbbBr/H2O | FL | Gastric cancer miRNAs | * | 91–559 pM | [62] | |

| PbCl2,CdCl2/2ATPA/DMF:EtOH | EC | CEA | 0.3–3 ng/mL | 0.03 pg/mL | Serum | [63] |

| AFP | 0.1 pg/mL | |||||

| FeCl3/2ATPA/H2O | PL | S. aureus | 40–41 × 08 CFU/mL | 31 CFU/mL | Cream pastry | [64] |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH | CL | H2O2 | 0.1–10 μM | 0.025 μM | Milk | [65] |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/H2O/AcOH,Pluronic F127 | FL | BPA | 5 × 10−14–2 × 10−9 M | 4.1 × 10−14 M | [66] | |

| Cd(NO3)2/2ATPA(Na)/H2O | FL | Parathion | 1 ppb–1 ppm | 1 ppb | Serum | [67] |

| Zn(NO3)2/Cbdcp,bpe/DMF or DMF:H2O/Aspirin/5FU | FL | HIV dsDNA | 1–80 nM | 10 pM | [68] | |

| HfCl4/AQPDC,DBP(Pt)/DMF/AcOH | PL/FL | O2 | 8–81 mmHg | n.d. | Cells | [69] |

| Imaging | ||||||

| ZrCl4/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH | FL | Hg2+ | 0.1–10 μM | 17.6 nM | Water | [70] |

| Dy(NO3)3/H3DcbcpBr/H2O/NaOH | FL | Ebola virus | 5–50 nM | 160 pM | [71] | |

| Cu(NO3)2/H2dcbbBr/H2O | FL | HIV dsDNA | 1–120 nM | 1.42 nM | [72] | |

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/H2O | UV–vis | H2O2 | 0–800 μM | 1.0 μM | Sewage | [73] |

| Phenol | 0–200 μM | |||||

| CuSO4/DTOA/H2O | FL | HIV virus | 10–100 nM | 3 nM | [74] | |

| Thrombin | 5–100 nM | 1.3 nM | ||||

| CuSO4/H3CmdrpBr,dps/H2O/NaOH | FL | HIV dsDNA | 10–50 nM | 196 pM | [75] | |

| Sudan RNA | 73 pM | |||||

| Cr(NO3)3/TPA/H2O/HF | FL | DNA | 0.1–14 nM | 73 pM | [76] | |

| Gd(NO3)3/TIA/DMF:H2O | FL | DNA | 0–50 nM | n.d. | [77] | |

| Eu(NO3)3/TDA/EtOH | FL | H2O2 | 5–150 μM | n.d. | Plasma | [78] |

| Cu(NO3)2/BTC/DMF:H2O:EtOH | CL | Dopamine | 0.01–0.70 μM | 2.3 nM | Urine | [79] |

| Plasma | ||||||

| Al(NO3)3/B4C/H2O | FL | HA | 0.05–8 mg/mL | 9 μg/mL | Urine | [80] |

| Eu(NO3)3,Tb(NO3)3/H2bpdc/MeOH:CHCl3 | FL | LPA | 1.4–43.3 μM | n.d. | [81] | |

| Zn(AcO)2/BPDC,adenine/DMF:H2O/HNO3 | FL | DCA | 50 nM–1 μM | 34 nM | Serum | [82] |

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrCl3/TPA/H2O | EC | H2O2 | 25–500 μM | 3.52 μM | Serum | [83] |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH | EC | miRNA-122 | 0.01 fM–10 pM | 0.003 fM | Serum | [84] |

| Blood | ||||||

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH | EC | Pb2+ | 0.005–1000 nM | 2 pM | Water | [85] |

| Zn(NO3)2/BPDC,adenine, Ru(bpy)3Cl2/DMF:H2O/HNO3 | ECL | miRNA-155 | 0.8 fM–1 nM | 0.3 fM | Serum | [86] |

| ZrCl4/TCPP/DMF/BA | FL | p53 gene | 0.01–10 nM | 0.005 nM | Serum | [87] |

| PSA | 0.05–10 ng/mL | 0.01 ng/mL | ||||

| ZrCl4/TPA/DMF/AcOH | PEC | PKA | 0.005–0.065 U/mL | 0.0049 U/mL | Cells | [88] |

| CrO3/BTC,BBDC/H2O/HF | EC | H2O2 | 0.5–3000 μM | 0.1 μM | Cells | [89] |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH | ECL | MUC1 | 1 fg/mL–1 ng/mL | 0.26 fg/mL | Cells | [90] |

| CeCl3/2ATPA/H2O:2-propanol | EC | ATP | 10 nM–1000 μM | 5.6 nM | Serum | [91] |

| Cr(NO3)3/TPA/H2O/HF | FL | Thrombin | 50 pM–100 nM | 15 pM | Serum | [92] |

| OTC | 10 nM–2 μM | 4.2 nM | Duck | |||

| FeCl3/H3TAB/DMF/TFA | EC | H2O2 | 0.5 μM–5 mM | 0.09 μM | [93] | |

| H3PMo12O40,CuCl2/1,10-phen/H2O | EC | Dopamine | 10−6–2 × 10−4 M | 80.4 × 10−9 M | Serum | [94] |

| Fe(AcO)3/FA/MeOH:H2O/NaOH | UV–vis | H2O2 | 2 × 10−6–2.03 × 10−5 M | 5.62 × 10−7 M | [95] | |

| AA | 2.57 × 10−6–1.01 × 10−5 M | 1.03 × 10−6 M | ||||

| FeCl3/TPA/DMF | EC | H2O2 | 0.1–2000 μM | 0.075 μM | Water | [96] |

| NO2− | 0.4–7000 μM | 0.36 μM | ||||

| ZrCl4/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH | EC | KANA | 0.002–100 nM | 0.16 pM | Milk | [97] |

| CAP | 0.19 pM | |||||

| Cu(NO3)2/beb,H2ada/H2O | EC | H2O2 | 0.05–3 μM | 0.014 μM | [98] | |

| FeCl3/TCPP/DMF:EtOH/HCl | EC | Pb2+ | 0.03–1000 nM | 0.02 nM | Water | [99] |

| Juices | ||||||

| Serum | ||||||

| Cu(NO3)2/TCPP,4bpy/Acetone:H2O/NaOH | EC | NO2− | 3.5–2800 μM | 1.1 μM | Pickle | [100] |

| Juice | ||||||

| CuCl2/H2Leu/CH3CN:EtOH/LiOH | EC | MBZ | 0.001–0.1 mM | 1.3 μM | [101] |

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn(NO3)2/[Ru(dcbpy)3]2+/PrOH:H2O | ECL | miRNA-141 | 1 fM–10 pM | 0.3 fM | Serum | [102] |

| Cu(NO3)2/TCPP/DMF:EtOH/TFA,PVP | FRET | CAP | 0.001–10 ng/mL | 0.3 pg/mL | Milk | [103] |

| Fish | ||||||

| Cu(NO3)2/2ATPA/DMF:CH3CN | FL | HXA | 10–2000 μM | 3.93 μM | Fish | [104] |

| Ni(NO3)2/TPA/DMF:H2O/NaOH | EC | Glucose | 4–5664 μM | 0.8 μM | Serum | [105] |

| ZrOCl2/H3NBB/DEF/TFA | EC | MUC1 | 0.001–0.5 ng/mL | 0.12 pg/mL | Serum | [106] |

| SPR | 0.65 pg/mL |

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator/NP) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co(NO3)2/2MI/MeOH:EtOH/Ag | EC | Glucose | 2–1000 μM | 0.66 μM | [107] | |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH/Au | EC | Gal-3 | 100 fg/mL–50 ng/mL | 33.33 fg/mL | Serum | [108] |

| ZrCl4/TPA/DMF/TFA,HCl/Ag | EC | CEA | 0.01–10 ng/mL | 0.31 pM | Serum | [109] |

| SPR | 4.0–250 ng/mL | 0.3 ng/mL | ||||

| Co(NO3)2/2MI/H2O/CTAB/AuPt | EC | LAG-3 | 0.01 ng/mL–1 μg/mL | 1.1 pg/mL | Serum | [110] |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH/AuPt | EC | ADRB1 | 1 fM–10 nM | 0.21 fM | Serum | [111] |

| FeCl3/2ATPA/DMF/AcOH/Pt | EC | FGFR3 | 0.1 fM–1 nM | 0.033 fM | Serum | [112] |

| PbCl2/β-CD/H2O:cyclohexanol/Et3N/Au | ECL | Insulin | 0.1 pg/mL–10 ng/mL | 0.042 pg/mL | [113] | |

| Cu(NO3)2/2ATPA/DMF:EtOH/PVP/Au | EC | miRNA-155 | 1 fM–10 nM | 0.35 fM | Serum | [114] |

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiCl2/TPA/DMF | EC | Glucose | 0.4–900 μM | 0.1 μM | Serum | [115] |

| Fe(NO3)3,ZrCl4, La(NO3)3/2ATPA/DMF | EC | Parathion-methyl | 10−12–10−8 | 3.2 × 10−13 | [116] | |

| 5 × 10−13–5 × 10−9 | 1.8 × 10−13 | |||||

| 10−13–5 × 10−9 g/mL | 5.8 × 10−14 g/mL | |||||

| CoCl2/2MI/MeOH | EC | Glucose | 5 × 10−12–2.05 × 10−10 M | 2 × 10−12 M | Serum | [117] |

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/MeOH | PEC | Alkaline phosphatase | 2–1500 U/L | 1.7 U/L | Serum | [118] |

| Al(NO3)3/NDC/H2O | EC | Glucose | 0.07–0.99 mM | 0.065 mM | [119] | |

| Fe(NO3)3/FA/DMF | FL | DNA | 3–150 nM | 1 nM | Serum | [120] |

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator/Core) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeCl3/TPA/DMF/NaOH/Fe3O4 | UV–vis | Glutathione | 0.55–3 μM | 36.9 nM | Serum | [121] |

| Cu(NO3)2/BTC/EtOH:H2O/Fe3O4,g-C3N4 | FL | OTA | 5–160 ng/mL | 2.57 ng/mL | Corn | [122] |

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/EtOH:H2O/GO-CaCO3@PDA | EC | Glucose | 1 μM–3.6 mM | 0.333 μM | Serum | [123] |

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/H2O/CdTe-QDs@PVP | FL | H2O2 | 1–100 nM | 0.29 nM | Serum | [124] |

| Urate oxidase | 0.1–50 U/L | 0.024 U/L | ||||

| Glucose oxidase | 1–100 U/L | 0.26 U/L | ||||

| Cu(NO3)2/BTC/DMF:EtOH/Y-Yb-Er-UCNPs@PAA | FL | BHB | 0.1–0.6 mg/mL | 0.062 mg/mL | [125] | |

| FeCl3/BTC/DMF/PS@Au@PVP | LSPR | Glucose | 2–40 mM | n.d. | [126] | |

| 2MI/DMF:H2O/Glass@FTO@ZnO | PEC | H2O2 | 0–4 mM | n.d. | Serum | [127] |

| Zn(AcO)2/2MI/H2O/AuNRs | LSPR | HSA | 250–1000 ng/mL | 130 ng/mL | [128] | |

| TiTB/2ATPA/DMF:EtOH/TiO2 | PEC | Acetochlor | 0.02–200 nM | 0.003 nM | Strawberry | [129] |

| Tomato | ||||||

| Cucumber | ||||||

| Greens |

| Composition (Metal Precursor/Organic Ligand/Solvent/Modulator/Core) | Sensing | Analyte | DR | LOD | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(NO3)2/BTC/EtOH:H2O/3D-KSCs | EC | Glucose | 44.9 μM–19 mM | 14.77 μM | Serum | [130] |

| [Fe3O(OOCCH3)6OH]/TCPP(Fe)/DMF/TFA/OMC | EC | H2O2 | 0.5–1830.5 μM | 0.45 μM | Cells | [131] |

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/MeOH/PS | EC | H2O2 | 0.09–3.6 mM | n.d. | Water | [132] |

| Milk | ||||||

| Beer | ||||||

| Cu(AcO)2/BTC/H2O:1-pentanol/PVP/GP | EC | Lactate | 0.05–22.6 mM | 5 μM | Sweat | [133] |

| Glucose | 0.05–1775.5 μM | 30 nM | ||||

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/ink/paper | FL | H2O2 | 20–120 mM | 20 mM | [134] | |

| AlCl3/H3TAB/DMF/TFA/3D-KSCs | EC | H2O2 | 0.387 μM–1.725 mM | 0.127 μM | [135] | |

| Cu(NO3)2/BTC/EtOH:H2O/GO | EC | H2O2 | 1 μM–5.6mM | 0.049 μM | Serum | [136] |

| Tb(NO3)3/H3TAB/MeOH,H2O,DMA/3D-KSCs | EC | H2O2 | 3.02–640 μM | 0.996 μM | Disinfector | [137] |

| ZrOCl2/TCPP/DMF/BA/PEDOT NTs | EC | Dopamine | 2 × 10−6–270 × 10−6 M | 4 × 10−8 M | Cells | [138] |

| Cu(OH)2/BTC/EtOH:H2O/GCE | EC | Glucose | 2 μM–4 mM | 0.6 μM | Serum | [139] |

| Zn(NO3)2/2MI/MeOH/PVP/GO | EC | H2O2 | 0.02–6 mM | 3.4 μM | [140] |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrasco, S. Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Development of Biosensors: A Current Overview. Biosensors 2018, 8, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios8040092

Carrasco S. Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Development of Biosensors: A Current Overview. Biosensors. 2018; 8(4):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios8040092

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrasco, Sergio. 2018. "Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Development of Biosensors: A Current Overview" Biosensors 8, no. 4: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios8040092

APA StyleCarrasco, S. (2018). Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Development of Biosensors: A Current Overview. Biosensors, 8(4), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios8040092