A Comprehensive Review of Biochemical Insights and Advanced Packaging Technologies for Shelf-Life Enhancement of Temperate Fruits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Maturity Index and Harvest of Temperate Fruits

3. Post-Harvest Biochemical Changes in Temperate Fruits

3.1. Apples

- (a)

- Water loss

- (b)

- Sunscald

- (c)

- Superficial Scald

- (d)

- Internal Browning

- (e)

- Enzymatic browning:

- (f)

- Water core:

3.2. Pear

- (a)

- Cork spot

- (b)

- Internal flesh browning:

- (c)

- Superficial scald:

- (d)

- Softening

3.3. Apricot, Peaches, and Nectarine

- (a)

- Brown rot

- (b)

- Softening

- (c)

- Gel breakdown:

- (d)

- Pit burn:

- (e)

- Chilling injury:

- (f)

- Mealiness:

- (g)

- Flesh Redness:

4. Packaging Interventions to Alleviate Storage Disorders

4.1. Conventional Packaging System

4.2. Biodegradable Polymers

- (a)

- Biomolecule derived

- (b)

- Synthetically derived biopolymers from natural biomass or synthetic materials.

- (c)

- Microorganism sourced.

4.3. Vacuum Packaging

4.4. Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP)

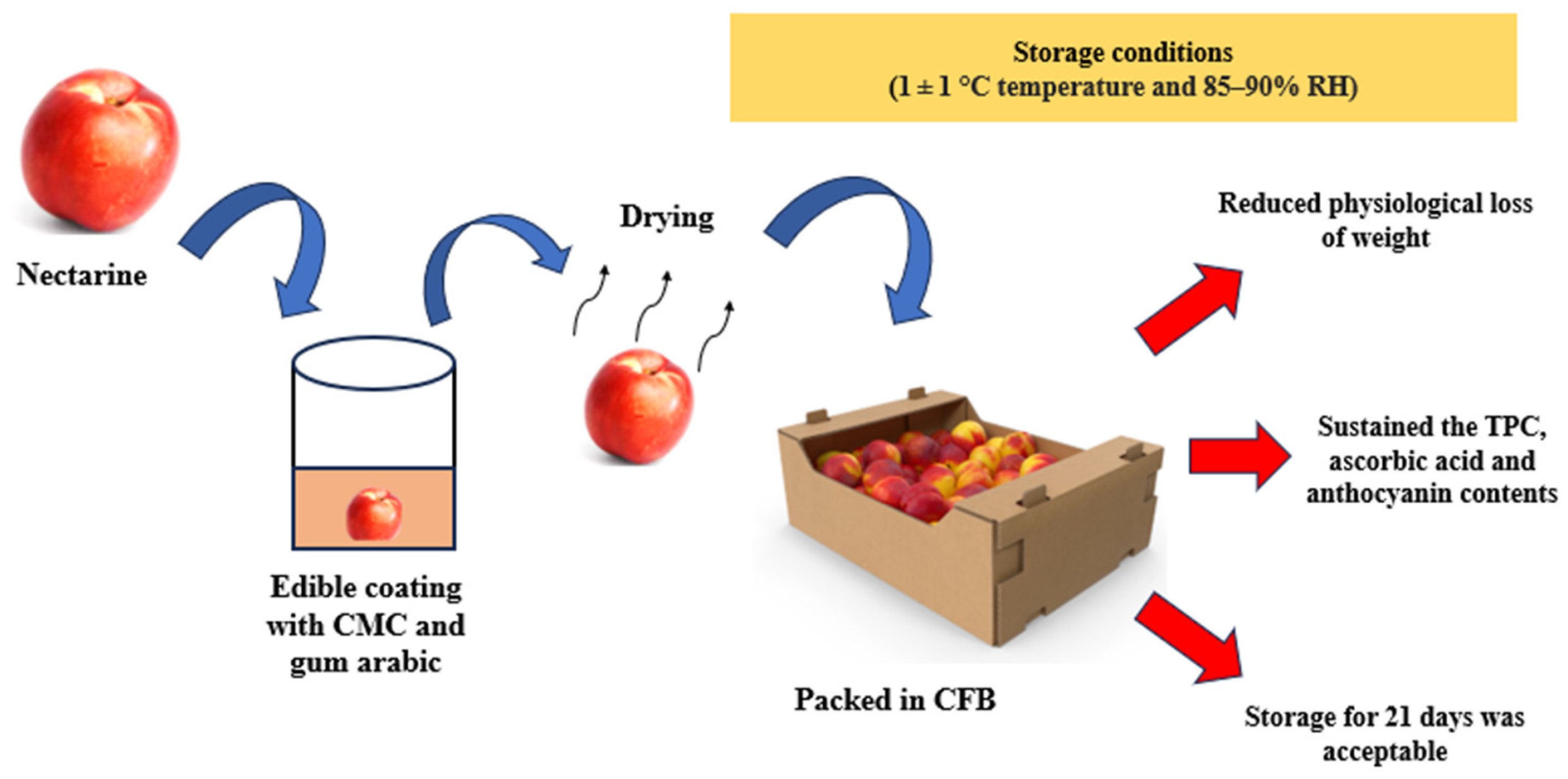

4.5. Edible Coating

4.6. Metal Oxide-Coated Multilayered Packaging System

4.7. Active Packaging

4.8. Intelligent Packaging

4.9. Nano-Packaging

5. Challenges and Potential Limitations of Advanced Packaging Interventions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Minocha, S.; Thomas, T.; Kurpad, A.V. Are ‘fruits and vegetables’ intake really what they seem in India? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, M.K.; Ahmed, N.; Singh, A.K.; Awasthi, O.P. Temperate tree fruits and nuts in India. Chron. Hortic. 2010, 50, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Luedeling, E. Climate change impacts on winter chill for temperate fruit and nut production: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 144, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.; Ramina, A. Temperate fruit species. In Horticulture: Plants for People and Places, Volume 1: Production Horticulture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Campoy, J.; Ruiz, D.; Egea, J. Dormancy in temperate fruit trees in a global warming context: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 130, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.-M.; Ezzat, A.; El-Ramady, H.; Alam-Eldein, S.M.; Okba, S.K.; Elmenofy, H.M.; Hassan, I.F.; Illés, A.; Holb, I.J. Temperate Fruit Trees under Climate Change: Challenges for Dormancy and Chilling Requirements in Warm Winter Regions. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamales, J.B. World temperate fruit production: Characteristics and challenges. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2011, 33, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzaffar, S.; Bhat, M.M.; Wani, T.A.; Wani, I.A.; Masoodi, F.A. Postharvest biology and technology of apricot. In Postharvest Biology and Technology of Temperate Fruits; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Masud, T.; Ali, A.; Abbasi, K.S.; Hussain, S. Influence of packaging material and ethylene scavenger on bio-chemical composition and enzyme activity of apricot cv. Habi at ambient storage. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 2015, 35, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mukama, M.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. Advances in design and performance evaluation of fresh fruit ventilated distribution packaging: A review. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonora, E.; Noferini, M.; Stefanelli, D.; Costa, G. A new simple modeling approach for the early prediction of harvest date and yield in nectarines. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 172, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalisi, A.; O’Connell, M.G.; Islam, M.S.; Goodwin, I. A Fruit Colour Development Index (CDI) to Support Harvest Time Decisions in Peach and Nectarine Orchards. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalisi, A.; O’Connell, M.G. Relationships between Soluble Solids and Dry Matter in the Flesh of Stone Fruit at Harvest. Analytica 2021, 2, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajcar, M.; Saletnik, B.; Zardzewiały, M.; Drygaś, B.; Czernicka, M.; Puchalski, C.; Zaguła, G. Method for determining fruit harvesting maturity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2016, 6, 773–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corelli-Grappadelli, L.; Lakso, A. Fruit development in deciduous tree crops as affected by physiological factors and environmental conditions (keynote). In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 636: XXVI International Horticultural Congress: Key Processes in the Growth and Cropping of Deciduous Fruit and Nut Trees; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS): Leuven, Belgium, 2004; pp. 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinati, S.; Rasori, A.; Varotto, S.; Bonghi, C. Rosaceae Fruit Development, Ripening and Post-harvest: An Epigenetic Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, M.J.; Argenta, L.C.; Mattheis, J.P.; Amarante, C.V.T.D.; Steffens, C.A. Relationship between dry matter content at harvest and maturity index and post-harvest quality of ‘Fuji’ apples. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2018, 40, e596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisosto, C.H. Establishing a Consumer Quality Index for Fresh Plums (Prunus salicina Lindell). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldicchi, A.; Farinelli, D.; Micheli, M.; Di Vaio, C.; Moscatello, S.; Battistelli, A.; Walker, R.; Famiani, F. Analysis of seed growth, fruit growth and composition and phospoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) occurrence in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Sci. Hortic. 2015, 186, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, R.; Rubio, P.; Contador, L.; Noferini, M.; Costa, G. Determination of harvest maturity of D’Agen plums using the chlorophyll absorbance index. Cienc. E Investig. Agrar. 2011, 38, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manera, F.J.; Legua, P.; Melgarejo, P.; Brotons, J.M.; Hernández, F.C.A.; Martínez, J.J. Determination of a colour index for fruit of pomegranate varietal group “Mollar de Elche”. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 150, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lecourt, J.; Bishop, G. Advances in Non-Destructive Early Assessment of Fruit Ripeness towards Defining Optimal Time of Harvest and Yield Prediction—A Review. Plants 2018, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minas, I.S.; Blanco-Cipollone, F.; Sterle, D. Accurate non-destructive prediction of peach fruit internal quality and physiological maturity with a single scan using near infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2021, 335, 127626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giné-Bordonaba, J.; Echeverria, G.; Duaigües, E.; Bobo, G.; Larrigaudière, C. A comprehensive study on the main physiological and biochemical changes occurring during growth and on-tree ripening of two apple varieties with different postharvest behaviour. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harker, F.; Feng, J.; Johnston, J.; Gamble, J.; Alavi, M.; Hall, M.; Chheang, S. Influence of postharvest water loss on apple quality: The use of a sensory panel to verify destructive and non-destructive instrumental measurements of texture. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 148, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.U.; Singh, Z.; Shah, H.M.S.; Kaur, J.; Woodward, A. Water Loss: A Postharvest Quality Marker in Apple Storage. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 2155–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Duan, X.; Shi, J.; Lu, W.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, Y. Effects of reactive oxygen species on cellular wall disassembly of banana fruit during ripening. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.A.; Andrews, P.K.; Davies, N.M. Physiological and biochemical responses of fruit exocarp of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) mutants to natural photo-oxidative conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1933–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.A.; Sepulveda, A.; Gonzalez-Talice, J.; Yuri, J.A.; Razmilic, I. Fruit water relations and osmoregulation on apples (Malus domestica Borkh.) with different sun exposures and sun-injury levels on the tree. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 161, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovchenko, A.E.; Avertcheva, O.V.; Merzlyak, M.N. Elevated sunlight promotes ripening-associated pigment changes in apple fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 40, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupan, A.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Slatnar, A.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R. Individual phenolic response and peroxidase activity in peel of differently sun-exposed apples in the period favorable for sunburn occurrence. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 1706–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsantili, E.; Rodov, V. Harvest and Postharvest Physiology and Technology of Fresh Fig Fruit. In Advances in Fig Research and Sustainable Production; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 193–232. [Google Scholar]

- Pusittigul, I.; Kondo, S.; Siriphanich, J. Internal browning of pineapple (Ananas comosus L.) fruit and endogenous concentrations of abscisic acid and gibberellins during low temperature storage. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 146, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tang, R.; Fan, K. Recent advances in postharvest technologies for reducing chilling injury symptoms of fruits and vegetables: A review. Food Chem. X 2023, 21, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellidou, I.; Buts, K.; Hatoum, D.; Ho, Q.T.; Johnston, J.W.; Watkins, C.B.; Schaffer, R.J.; Gapper, N.E.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Rudell, D.R.; et al. Transcriptomic events associated with internal browning of apple during postharvest storage. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Q.T.; Verboven, P.; Verlinden, B.E.; Schenk, A.; Delele, M.A.; Rolletschek, H.; Vercammen, J.; Nicolaï, B.M. Genotype effects on internal gas gradients in apple fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 2745–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, S.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Lopes-Da-Silva, J.A.; Delgadillo, I.; Van Loey, A.; Smout, C.; Hendrickx, M. Effect of thermal blanching and of high pressure treatments on sweet green and red bell pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.M.; Kwon, E.-B.; Lee, B.; Kim, C.Y. Recent Trends in Controlling the Enzymatic Browning of Fruit and Vegetable Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrufo-Hernández, N.A.; Palma-Orozco, G.; Beltrán, H.I.; Nájera, H. Beltrán Purification, partial biochemical characterization and inactivation of polyphenol oxidase from Mexican Golden Delicious apple (Malus domestica). J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, e12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales-Delgado, S. Polyphenoloxidase (PPO): Effect, Current Determination and Inhibition Treatments in Fresh-Cut Produce. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, S.; Anthony, B.; Sesillo, F.B.; Masia, A.; Musacchi, S. Determination of Post-Harvest Biochemical Composition, Enzymatic Activities, and Oxidative Browning in 14 Apple Cultivars. Foods 2021, 10, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Hayakawa, F.; Tatsuki, M. Flavor and Texture Characteristics of ‘Fuji’ and Related Apple (Malus domestica L.) Cultivars, Focusing on the Rich Watercore. Molecules 2020, 25, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2016. Available online: www.fao.org (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Wawrzyńczak, A.; Rutkowski, K.P.; Kruczyńska, D.E. Fruit Quality of Some Pear Cultivars as Influenced by Storage Temperature; Research Institute of Pomology and Floriculture: Skierniewice, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Jiao, Q.; Wang, R.; Ma, C. Investigation and analysis of relationship between mineral elements alteration and cork spot physiological disorder of Chinese pear ‘Chili’ (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 260, 108883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, F. Occurrence of Physiological Disorders in Japanese Pear Fruit and Advances in Research on these Disorders. Hortic. Res. 2017, 16, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, P.; Li, A.; Qiu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, R.; Ma, C.; Song, J.; Cui, Z.; et al. Mineral and Metabolome Analyses Provide Insights into the Cork Spot Disorder on ‘Akizuki’ Pear Fruit. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Singh, Z.; Khan, A.S. Delayed harvest and cold storage period influence ethylene production, fruit firmness and quality of ‘Cripps Pink’ apple. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 2520–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naschitz, S.; Naor, A.; Sax, Y.; Shahak, Y.; Rabinowitch, H.D. Photo-oxidative sunscald of apple: Effects of temperature and light on fruit peel photoinhibition, bleaching and short-term tolerance acquisition. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenta, L.C.; Anese, R.D.O.; Thewes, F.R.; Wood, R.M.; Nesi, C.N.; Neuwald, D.A. Maintenance of ‘Luiza’ apple fruit quality as affected by postharvest practices. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2022, 44, e905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Hossain, M.K. Nanoparticle-Based Polymer Composites; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, Z. Review of fruit cork spot disorder of Asian pear (Pyrus spp.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1211451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, C.; Lammertyn, J.; Ho, Q.T.; Verboven, P.; Verlinden, B.; Nicolaï, B.M. Browning disorders in pear fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaracho, N.; Reig, G.; Kalluri, N.; Arús, P.; Eduardo, I. Inheritance of Fruit Red-Flesh Patterns in Peach. Plants 2023, 12, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuchande, T.; Carvalho, S.M.; Guterres, U.; Fidalgo, F.; Isidoro, N.; Larrigaudiere, C.; Vasconcelos, M.W. Dynamic controlled atmosphere for prevention of internal browning disorders in ‘Rocha’ pear. LWT 2016, 65, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, H.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Inhibitory effects of propyl gallate on membrane lipids metabolism and its relation to increasing storability of harvested longan fruit. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, C. Metabolic Characterisation of Browning Disorders in Conference Pears. Ph.D. Thesis, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Veltmann, R.; Peppelenbos, H. A proposed mechanism behind the development of internal browning in pears (Pyrus communis cv conference). In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 600: VIII International Controlled Atmosphere Research Conference; Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 8–13 July 2001, International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS): Leuven, Belgium, 2003; pp. 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrigaudière, C.; Candan, A.P.; Giné-Bordonaba, J.; Civello, M.; Calvo, G. Unravelling the physiological basis of superficial scald in pears based on cultivar differences. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 213, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, S.; Watkins, C.B. Superficial scald, its etiology and control. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 65, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R. Study of physiological change in Dangshansuli pear of superficial scald. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering (RSETE), Nanjing, China, 24–26 June 2011; pp. 3497–3503. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Zhao, L.; Du, G. Ethylene promotes fruit softening of ‘Nanguo’ pear via cell wall degradation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 4770–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdunek, A.; Kozioł, A.; Cybulska, J.; Lekka, M.; Pieczywek, P.M. The stiffening of the cell walls observed during physiological softening of pears. Planta 2016, 243, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, L.O.; Pacheco, I.; Mercier, V.; Faoro, F.; Bassi, D.; Bornard, I.; Quilot-Turion, B. Brown Rot Strikes Prunus Fruit: An Ancient Fight Almost Always Lost. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4029–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Marshall, R.; Ogwaro, J.; Feng, R.; Wohlers, M.; Woolf, A. Postharvest storage temperatures impact significantly on apricot fruit quality. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 880: International Symposium Postharvest Pacifica 2009—Pathways to Quality: V International Symposium on Managing Quality in Chains + Australasian Postharvest Horticultural Conference; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2010; pp. 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Prakash, R.; Marshall, R.; Schröder, R. Effect of harvest maturity and cold storage on correlations between fruit properties during ripening of apricot (Prunus armeniaca). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 82, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Yuan, S.; Pan, H.; Wang, R.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Effect of yeast mannan treatments on ripening progress and modification of cell wall polysaccharides in tomato fruit. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Shu, C.; Zhao, K.; Wang, X.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Regulation of apricot ripening and softening process during shelf life by post-storage treatments of exogenous ethylene and 1-methylcyclopropene. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 232, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Stanley, J.; Othman, M.; Woolf, A.; Kosasih, M.; Olsson, S.; Clare, G.; Cooper, N.; Wang, X. Segregation of apricots for storage potential using non-destructive technologies. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 86, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushesh saba, M.; Arzani, K.; Barzegar, M. Postharvest polyamine application alleviates chilling injury and affects apricot storage ability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 8947–8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, S.; Crisosto, C.H. Chilling injury in peach and nectarine. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2005, 37, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisosto, C.H.; Mitchell, F.G.; Ju, Z. Susceptibility to Chilling Injury of Peach, Nectarine, and Plum Cultivars Grown in California. HortScience 1999, 34, 1116–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, G.D.; Gautam, D.M.; Baral, D.R.; KC, G.; Paudyal, K.P. Evaluation of Packaging Materials for Transportation of Apple Fruits in CFB Boxes. Int. J. Hortic. 2017, 7, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Deka, B.C.; Singh, A.; Patel, R.K.; Paul, D.; Misra, L.K.; Ojha, H. Extension of shelf life of pear fruits using different packaging materials. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 49, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosie, T.; Woldetsadik, K.; Azene, M. Quality of Peach (Prunus persica L.) Genotypes Packed in LDPE Plastic Packaging under Different Storage Conditions. Agric. Food Sci. Res. 2019, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbudak, B.; Eris, A. Physical and chemical changes in peaches and nectarines during the modified atmosphere storage. Food Control 2004, 15, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.S.; Bound, S.A.; Swarts, N.D. Internal flesh browning in apple and its predisposing factors—A review. Physiologia 2023, 3, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Yang, B.; Fan, B.; Zhang, H.; Weng, Y. Enhancement of Mechanical and Barrier Property of Hemicellulose Film via Crosslinking with Sodium Trimetaphosphate. Polymers 2021, 13, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Rempel, C.; Liu, Q. Treatments of protein for biopolymer production in view of processability and physical properties: A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangar, S.P.; Whiteside, W.S.; Suri, S.; Barua, S.; Phimolsiripol, Y. Native and modified biodegradable starch-based packaging for shelf-life extension and safety of fruits/vegetables. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 58, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Contreras, F.; García-Caldera, N.; de la Rosa, J.D.P.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Núñez-Delicado, E.; Gabaldón, J.A. Effect of PLA Active Packaging Containing Monoterpene-Cyclodextrin Complexes on Berries Preservation. Polymers 2021, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiak, E.; Linke, M.; Debeaufort, F.; Lenart, A.; Geyer, M. Impact of Biodegradable Materials on the Quality of Plums. Coatings 2022, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsuga, M.; Kawamura, Y.; Tanamoto, K. Migration of lactic acid, lactide and oligomers from polylactide food-contact materials. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2008, 25, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, D.R.; Clarke, R. Modeling of modified atmosphere packaging based on designs with a membrane and perfo-rations. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 208, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, S.; Ahmad, F.; Zaidi, S. Preparation and characterization of biodegradable food packaging films using lemon peel pectin and chitosan incorporated with neem leaf extract and its application on apricot fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoya, G.I.; Vaudagna, S.R.; Polenta, G. Effect of high pressure processing and vacuum packaging on the preservation of fresh-cut peaches. LWT 2015, 62, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koruk, H.; Sanliturk, K.Y. Detection of air leakage into vacuum packages using acoustic measurements and estimation of defect size. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 114, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaraj, S.; Goswami, T.K.; Mahajan, P.V. Applications of Plastic Films for Modified Atmosphere Packaging of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Food Eng. Rev. 2009, 1, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, R.; Auras, R.; Siddiq, M.; Dolan, K.D.; Harte, B. Effect of modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) and NatureSeal® treatment on the physico-chemical, microbiological, and sensory quality of fresh-cut d’Anjou pears. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 23, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, G.; Shen, C.; Yan, H.; Guan, J.; Yang, K. The effects of modified atmosphere packaging on core browning and the expression patterns of PPO and PAL genes in ‘Yali’ pears during cold storage. LWT 2015, 60, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz-Korkut, G.; Kucukmehmetoglu, S.; Gunes, G. Effects of modified atmosphere packaging on physicochemical properties of fresh-cut ‘Deveci’ pears. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleb, O.J.; Geyer, M.; Mahajan, P.V. Mathematical modeling for micro-perforated films of fruits and vegetables used in packaging. In Innovative Packaging of Fruits and Vegetables: Strategies for Safety and Quality Maintenance; Apple Academic Press: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2018; pp. 259–273. [Google Scholar]

- Mangaraj, S.; Sadawarti, M.; Prasad, S. Assessment of Quality of Pears Stored in Laminated Modified Atmosphere Packages. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 1110–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, P.; Zhang, M.; Fan, K.; Guo, Z. Microporous modified atmosphere packaging to extend shelf life of fresh foods: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.; Castle, L.; Oldring, P.K.; Moschakis, T.; Wedzicha, B.L. Factors affecting migration kinetics from a generic epoxy-phenolic food can coating system. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muftuoğlu, F.; Ayhan, Z.; Esturk, O. Modified Atmosphere Packaging of Kabaaşı Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L. ‘Kabaaşı’): Effect of Atmosphere, Packaging Material Type and Coating on the Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Quality. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2010, 5, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorostkar, M.; Moradinezhad, F.; Ansarifar, E. Influence of Active Modified Atmosphere Packaging Pre-treatment on Shelf Life and Quality Attributes of Cold Stored Apricot Fruit. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2022, 22, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Castillo, S.; Guillén, F.; Valero, D. The use of natural antifungal compounds improves the beneficial effect of MAP in sweet cherry storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2005, 6, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocculi, P.; Romani, S.; Rosa, M.D.; Tonutti, P.; Bacci, A. Influence of ozonated water on the structure and some quality parameters of whole strawberries in modified atmosphere packaging (MAP). In ISHS Acta Horticulturae 682: V International Postharvest Symposium; Verona, Italy, International Society for Horticultural Science, 2005; pp. 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastromatteo, M.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Combined effect of active coating and MAP to prolong the shelf life of minimally processed kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa cv. Hayward). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Abreu, M.; Correia, L.; Beirão-Da-Costa, S.; Leitão, E.; Beirão-Da-Costa, M.L.; Empis, J.; Moldão-Martins, M. Metabolic response to combined mild heat pre-treatments and modified atmosphere packaging on fresh-cut peach. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 222, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, S.; Yu, R.; Li, P.; Zhou, C.; Qu, Y.; Li, H.; Luo, H.; Yu, L. Co-Application of 1-MCP and Laser Microporous Plastic Bag Packaging Maintains Postharvest Quality and Extends the Shelf-Life of Honey Peach Fruit. Foods 2022, 11, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winotapun, C.; Issaraseree, Y.; Sirirutbunkajal, P.; Leelaphiwat, P. CO2 laser perforated biodegradable films for modified atmosphere packaging of baby corn. J. Food Eng. 2022, 341, 111356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allende, A.; Marín, A.; Buendía, B.; Tomás-Barberán, F.; Gil, M.I. Impact of combined postharvest treatments (UV-C light, gaseous O3, superatmospheric O2 and high CO2) on health promoting compounds and shelf-life of strawberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 46, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, K.; Thirunavookarasu, N.; Chidanand, D.V. Recent advances in edible coating of food products and its legis-lations: A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100623. [Google Scholar]

- Morsy, N.E.; Rayan, A.M. Effect of different edible coatings on biochemical quality and shelf life of apricots (Prunus armenica L. cv Canino). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 3173–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayarajan, S.; Sharma, R.R. Postharvest life and quality of ‘Snow Queen’ nectarine (Prunus persica var. nucipersica) as influenced by edible coatings during cold storage. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2020, 42, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, M.S.; Caner, C. Understanding the effects of various edible coatings on the storability of fresh cherry. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2010, 23, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Sarengaowa; Feng, K. Effect of Edible Coating on the Quality and Antioxidant Enzymatic Activity of Postharvest Sweet Cherry (Prunusavium L.) during Storage. Coatings 2022, 12, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradinezhad, F.; Adiba, A.; Ranjbar, A.; Dorostkar, M. Edible coatings to prolong the shelf life and improve the quality of subtropical fresh/fresh-cut fruits: A review. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Aadil, R.M.; Amoussa, A.M.O.; Bashari, M.; Abid, M.; Hashim, M.M. Application of chitosan-based apple peel polyphenols edible coating on the preservation of strawberry (Fragaria ananassa cv Hongyan) fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 45, e15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, H.J.; Lee, C.Y.; Choi, W.Y. Extending shelf-life of minimally processed apples with edible coatings and antibrowning agents. LWT 2003, 36, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Pristijono, P.; Scarlett, C.J.; Bowyer, M.; Singh, S.; Vuong, Q.V. Starch-based edible coating formulation: Optimization and its application to improve the postharvest quality of “Cripps pink” apple under different temperature regimes. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 22, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.; Varney, C.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Tang, J.; Selim, F.; Sablani, S.S. The impact of microwave-assisted thermal sterilization on the morphology, free volume, and gas barrier properties of multilayer polymeric films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vähä-Nissi, M.; Pitkänen, M.; Salo, E.; Kenttä, E.; Tanskanen, A.; Sajavaara, T.; Putkonen, M.; Sievänen, J.; Sneck, A.; Rättö, M.; et al. Antibacterial and barrier properties of oriented polymer films with ZnO thin films applied with atomic layer deposition at low temperatures. Thin Solid Films 2014, 562, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struller, C.F.; Kelly, P.J.; Copeland, N.J. Aluminum oxide barrier coatings on polymer films for food packaging ap-plications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2014, 241, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struller, C.; Kelly, P.; Copeland, N. Conversion of aluminium oxide coated films for food packaging applications—From a single layer material to a complete pouch. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 20, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, A.; Bhunia, K.; Rasco, B.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Development of an Oxygen Sensitive Model Gel System to Detect Defects in Metal Oxide Coated Multilayer Polymeric Films. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, S.; Sonar, C.R.; Albahr, Z.; Alqahtani, O.; Collins, B.A.; Sablani, S.S. Pressure-assisted thermal sterilization of avocado puree in high barrier polymeric packaging. LWT 2022, 155, 112960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Parhi, A.; Tang, Z.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Storage stability of vitamin C fortified purple mashed potatoes processed with microwave-assisted thermal sterilization system. Food Innov. Adv. 2023, 2, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahr, Z.; Promsorn, J.; Tang, Z.; Ganjyal, G.M.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Storage and thermal stability of selected vegetable purees processed with microwave-assisted thermal sterilization. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandhini, J.; Bellarmin, M.; Prakash, S.S.; Sri, D.S.; Karthikeyan, E. Advancements in metal oxide bio-nanocomposites for sustainable food packaging: Fabrication, applications, and future prospectives. Food Bioeng. 2024, 3, 438–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.K.; Sooch, B.S. Biodegradable nano-reinforced packaging with improved functionality to extend the freshness and longevity of Plums Oemleria cerasiformis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifmalinda, I.; Kurnia, S.A.; Cherie, D. Characteristics of Edible Film from Corn Starch (Zea mays L.) with Additional Glycerol and Variations of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles. J. Appl. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Thakur, K.S. Active packaging technology to retain storage quality of pear cv. “Bartlett” during shelf-life periods under ambient holding after periodic cold storage. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2020, 33, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yun, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, P. Effect of nano-ZnO-coated active packaging on quality of fresh-cut ‘Fuji’ apple. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1947–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Forero, A.; Agudelo-Rodríguez, G.; Herrera, A.O.; Castellanos, D.A. Modeling and simulation of an active packaging system with moisture adsorption for fresh produce. Application in ‘Hass’ avocado. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjarasskul, T.; Tananuwong, K.; Krochta, J.M. Whey Protein Film with Oxygen Scavenging Function by Incorporation of Ascorbic Acid. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, E561–E568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, K.K.; Singh, S.; Lee, Y.S. Oxygen scavenging films in food packaging. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.E.; Andler, S.M.; Lincoln, C.; Goddard, J.M.; Talbert, J.N. Oxygen scavenging polymer coating prepared by hydrophobic modification of glucose oxidase. J. Coatings Technol. Res. 2017, 14, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Giuseppe, F.; Coffigniez, F.; Aouf, C.; Guillard, V.; Torrieri, E. Activated gallic acid as radical and oxygen scavenger in biodegradable packaging film. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Neogi, S. Oxygen scavengers for food packaging applications: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha Neto, A.C.; Beaudry, R.; Maraschin, M.; Di Piero, R.M.; Almenar, E. Double-bottom antimicrobial packaging for apple shelf-life extension. Food Chem. 2019, 279, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Martínez, A.; Garre, A.; Iguaz, A.; Maldonado-Guzmán, P.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Kinetics of carvacrol release from active paper packaging for fresh fruits and vegetables under conditions of open and closed package. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 37, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Martínez, A.; López-Gómez, A.; Martínez-Hernández, G.B. Potential of Essential Oils from Active Packaging to Highly Reduce Ethylene Biosynthesis in Broccoli and Apples. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, V.; Garavaglia, L.; Giacalone, G. The Postharvest Quality of Fresh Sweet Cherries and Strawberries with an Active Packaging System. Foods 2019, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Prado, P.; Rodriguez-Lafuente, A.; Nerin, C. Active label-based packaging to extend the shelf-life of “Calanda” peach fruit: Changes in fruit quality and enzymatic activity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2011, 60, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, S.; Singh, V.; Jyoti, S.; Shivhare, U. Mechanical properties and antimicrobial efficacy of active wrapping paper for primary packaging of fruits. Food Biosci. 2013, 3, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, S.; Priyadarshini, S.R.; Leena, M.M.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Intelligent packaging: Trends and applications in food systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, A.; Llobet, E.; Ramirez, J.; Ivanov, P.; Fonseca, L.; Zampolli, S.; Scorzoni, A.; Becker, T.; Marco, S.; Wollenstein, J. An RFID reader with onboard sensing capability for monitoring fruit quality. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 127, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Jemric, T.; Wang, X. Quality Monitoring and Analysis of Xinjiang ‘Korla’ Fragrant Pear in Cold Chain Logistics and Home Storage with Multi-Sensor Technology. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Xing, S.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X. Multi-Sensors Enabled Dynamic Monitoring and Quality Assessment System (DMQAS) of Sweet Cherry in Express Logistics. Foods 2020, 9, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Guo, M.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J.; Yue, Z. Research on Strawberry Cold Chain Transportation Quality Perception Method Based on BP Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Ashaolu, T.J. Applications of nano-materials in food packaging: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, e13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardesh, A.S.K.; Badii, F.; Hashemi, M.; Ardakani, A.Y.; Maftoonazad, N.; Gorji, A.M. Effect of nanochitosan based coating on climacteric behavior and postharvest shelf-life extension of apple cv. Golab Kohanz. LWT 2016, 70, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, S.; Rahemi, M.; Ramezanian, A. Comparison of nano-calcium and calcium chloride spray on postharvest quality and cell wall enzymes activity in apple cv. Red Delicious. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 240, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Kalia, A.; Thakur, A. Effect of biodegradable chitosan–rice-starch nanocomposite films on post-harvest quality of stored peach fruit. Starch-Stärke 2017, 69, 1600208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, M.; Adhikari, B. The Effects of Ultrasound Treatment and Nano-zinc Oxide Coating on the Physiological Activities of Fresh-Cut Kiwifruit. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 7, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Graü, M.; Tapia, M.; Rodríguez, F.; Carmona, A.; Martin-Belloso, O. Alginate and gellan-based edible coatings as carriers of antibrowning agents applied on fresh-cut Fuji apples. Food Hydrocoll. 2007, 21, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.R.; Cassani, L.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Soliva-Fortuny, R. Effects of polysaccharide-based edible coatings enriched with dietary fiber on quality attributes of fresh-cut apples. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 7795–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Rojas-Graü, M.A.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Use of antimicrobial nanoemulsions as edible coatings: Impact on safety and quality attributes of fresh-cut Fuji apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 105, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sethi, S.; Sharma, R.R.; Singh, S.; Varghese, E. Improving the shelf life of fresh-cut ‘Royal Delicious’ apple with edible coatings and anti-browning agents. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3767–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.; Palou, L.; Monteiro, A.R.; Pérez-Gago, M.B. Effect of antifungal hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-beeswax edible coatings on gray mold development and quality attributes of cold-stored cherry tomato fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 92, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.; Singh, S.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, K.; Yadav, K.; Bishnoi, M.; Singh, J.; Mehta, S. Enhancing grape preservation: The synergistic effect of curry leaf essential oil in buckwheat starch-chitosan composite coatings. Food Control 2024, 169, 111001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftoonazad, N.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Marcotte, M. Shelf-life extension of peaches through sodium alginate and methyl cellulose edible coatings. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Y.; Du, X.-L.; Liu, Y.; Tong, L.-J.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.-L. Rhubarb extract incorporated into an alginate-based edible coating for peach preservation. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M.E.; Timón, M.L.; Petrón, M.J.; Andrés, A.I. Effect of Chitosan, Pectin and Sodium Caseinate Edible Coatings on Shelf Life of Fresh-Cut P runus persica var. Nectarine. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 2687–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ullah, S.; Zeb, A.; Bibi, L.; Sarwar, R. Enhanced preservation of postharvest peaches with an edible composite coating solution of chitosan, tannic acid, and beeswax. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandane, A.S.; Dave, R.K.; Rao, T.V.R. Optimization of edible coating formulations for improving postharvest quality and shelf life of pear fruit using response surface methodology. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 54, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, O.A.; Zaidi, S.; Islam, R.U.; Naseem, S.; Junaid, P.M. Enhanced shelf-life of peach fruit in alginate based edible coating loaded with TiO2 nanoparticles. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 182, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yan, Y.; Gu, C.; Sun, J.; Han, Y.; Huangfu, Z.; Song, F.; Chen, J. Preparation and Characterization of Phenolic Acid-Chitosan Derivatives as an Edible Coating for Enhanced Preservation of Saimaiti Apricots. Foods 2022, 11, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, E.H.A.; Elnaggar, I.A.; El-Wahed, A.E.-W.N.A.; Taha, I.M.; Al-Jumayi, H.A.; Elhamamsy, S.M.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Fahmy, A. Effect of Chitosan Nanoparticles as Edible Coating on the Storability and Quality of Apricot Fruits. Polymers 2022, 14, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Li, T.; Ge, X. Studies on the effect of cinnamon essential oil-micelles combined with 1-MCP/PVA film on postharvest preservation of apricots. Food Control 2024, 162, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, H.Y.; Mohtasebi, S.S.; Tajeddin, B.; Taherimehr, M.; Tabatabaeekoloor, R.; Firouz, M.S.; Javadi, A. The Effect of a New Bionanocomposite Packaging Film on Postharvest Quality of Strawberry at Modified Atmosphere Condition. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormanli, E.; Uluturk, B.A.; Bozdogan, N.; Bayraktar, O.; Tavman, S.; Kumcuoglu, S. Development of a novel, sustainable, cellulose-based food packaging material and its application for pears. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Perez, B.E.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Velazquez, G.; Hernández-López, M.; Ventura-Aguilar, R.I.; Romero-Bastida, C.A. Application of Chitosan Bags Added with Cinnamon Leaf Essential Oil as Active Packaging to Inhibit the Growth of Penicillium crustosum in D’Anjou Pears. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 31, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alique, R.; Martínez, M.A.; Alonso, J. Influence of the modified atmosphere packaging on shelf life and quality of Navalinda sweet cherry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2003, 217, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Upadhyay, A. Nanocomposites: An Innovative Technology for Fruit and Vegetable Preservation. In Recent Advances in Postharvest Technologies, Volume 2: Postharvest Applications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 199–224. [Google Scholar]

- Sganzerla, W.G.; Rosa, G.B.; Ferreira, A.L.A.; da Rosa, C.G.; Beling, P.C.; Xavier, L.O.; Hansen, C.M.; Ferrareze, J.P.; Nunes, M.R.; Barreto, P.L.M.; et al. Bio-active food packaging based on starch, citric pectin and functionalized with Acca sellowiana waste by-product: Characteri-zation and application in the postharvest conservation of apple. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, H.; Li, F.; Xin, Z.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Q. Effect of Nano-Packing on Preservation Quality of Fresh Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa Duch. cv Fengxiang) during Storage at 4 °C. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C236–C240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Anjum, M.A.; Nawaz, A.; Naz, S.; Ejaz, S.; Saleem, M.S.; Haider, S.T.; Hasan, M.U. Effect of gum arabic coating on antioxidative enzyme activities and quality of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) fruit during ambient storage. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.G.; Ingber, D.E. Manufacturing of Large-Scale Functional Objects Using Biodegradable Chitosan Bioplastic. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2014, 299, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Guo, H. Progress in the Degradability of Biodegradable Film Materials for Packaging. Membranes 2022, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Aguilera, R.; Oliveira, J.C. Review of Design Engineering Methods and Applications of Active and Modified Atmosphere Packaging Systems. Food Eng. Rev. 2009, 1, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Li, B.; Lin, Q.-B.; Wu, H.-J.; Chen, Y. Migration of silver from nanosilver–polyethylene composite packaging into food simulants. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2011, 28, 1758–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegoyen, Y.; Nerín, C. Nanoparticle release from nano-silver antimicrobial food containers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 62, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumbudsanpharoke, N.; Ko, S. Nano-food packaging: An overview of market, migration research, and safety regulations. J. Food Sci. 2015, 80, R910–R923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.NO | Packaging Material/Technology Description | Fruits | Properties of Film/Coating Material/Storage Conditions | Effect on Fruit Matrix | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Polysaccharide based edible coating with NAC# and CC and packed in PP trays | Fresh cut apples | PP permeability in trays was

|

| [149] |

| 2 | Alginate, pectin and gellan gum edible coating with ascorbic acid and CaCl2 with apple fiber and inulin | Fresh-cut Golden Delicious apple cubes |

| [150] | |

| 3 | Nanoemulsions of sodium alginate with lemon essential oil | Fresh cut Fuji apples |

|

| [151] |

| 4 | Edible coating with SemperfreshTM, NiprofreshTM, and lac-based | Plums cv. Santa Rosa | Storage for 35 days 2 ± 1° C and 85–90% RH |

| [152] |

| 5 | Composite edible coating with hydroxypropyl methylcellulose/beeswax with antifungal agents—sodium methyl paraben, sodium ethyl paraben, and potassium sorbate | Plums cv. Friar | Storage for 22 days at 1 °C + 5 days at 20 °C |

| [153] |

| 6 | Composite Edible coating of buckwheat starch/xanthan gum/lemon essential oil | Plum | 2:1 ratio of BS and Xanthan gum with 1.25% LEO had the highest antioxidant (73.3%) and antimicrobial efficiency |

| [154] |

| 7 | Edible coating of sodium alginate, and methyl cellulose | Peach |

|

| [155] |

| 8 | Edible coating of Rhubarb extract/Sodium alginate | Peach cv. Baihua |

|

| [156] |

| 9 | Edible coating (chitosan, sodium caseinate, pectin) followed by MAP (PP trays with pore diameter of 100 μm) | Fresh-cut Nectarine |

|

| [157] |

| 10 | Edible composite coating of chitosan, tannic acid, and bees wax | Peaches |

|

| [158] |

| 11 | Edible composite coating of soy protein isolate SPI/HPMC/olive oil/potassium sorbate PS | Pear cv. Babughosha |

|

| [159] |

| 12 | Edible nanoemulsions composite coating of alginate/TiO2 nanoparticles/mousami peel extract | Peach | _ |

| [160] |

| 13 | Edible composite coating using free radical grafting with caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid with chitosan | Saimati apricots |

|

| [161] |

| 14 | Edible coating comparison of chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles | Apricots |

|

| [162] |

| 15 | Electro-spun nanofiber of cinnamon essential oil with polyvinyl alcohol and 1-methylcyclopropene | Apricots | _ |

| [163] |

| 16 | Bio-nano-composite based MAP | Strawberry |

|

| [164] |

| 17 | Electrospray coating of cellulose-based active packaging with fulvic acid and sericin | Pear | Storage at 7 °C for 90 days |

| [165] |

| 18 | Active packaging with montmorillonite and cinnamon leaf essential oil in chitosan bag | Pear | _ |

| [166] |

| 19 | MAP with microperforated PP bags (0.55 mol cm/cm2 atm day and 0.30 mol cm/cm2 atm day) | Navalinda sweet cherries | Storage for 8 days at 4 °C continued with 4 days at 8 °C |

| [167] |

| 20 | Active NanoPackaging with nano-zinc oxide in PVC | Fresh cut Fuji apples | Storage at 4 °C for 12 days |

| [168] |

| 21 | Active packaging using Pinhão starch/citrus pectin/Feijoa Peel Flour (0, 0.4, 1, 2, 3 and 4% application) | Apples | Storage at room temperature for 15 days |

| [169] |

| 22 | Nano-packaging with PE | Strawberry | Storage at 4 °C for 12 days |

| [170] |

| 23 | Edible coating with Gum Arabic | Apricots | Storage at 20 ± 1 °C for 8 days |

| [171] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nagaraja, S.K.; Kumar, P.; R, K.; Nabi, S.U.; Mir, J.I.; Verma, M.K.; Kalkisim, O.; Akbulut, M.; Kwon, Y.B.; Kang, H.-M.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Biochemical Insights and Advanced Packaging Technologies for Shelf-Life Enhancement of Temperate Fruits. Biosensors 2026, 16, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020094

Nagaraja SK, Kumar P, R K, Nabi SU, Mir JI, Verma MK, Kalkisim O, Akbulut M, Kwon YB, Kang H-M, et al. A Comprehensive Review of Biochemical Insights and Advanced Packaging Technologies for Shelf-Life Enhancement of Temperate Fruits. Biosensors. 2026; 16(2):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020094

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagaraja, Sharath Kumar, Puneet Kumar, Kavitha R, Sajad Un Nabi, Javid Iqbal Mir, Mahendra Kumar Verma, Ozgun Kalkisim, Mustafa Akbulut, Yong Beom Kwon, Ho-Min Kang, and et al. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review of Biochemical Insights and Advanced Packaging Technologies for Shelf-Life Enhancement of Temperate Fruits" Biosensors 16, no. 2: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020094

APA StyleNagaraja, S. K., Kumar, P., R, K., Nabi, S. U., Mir, J. I., Verma, M. K., Kalkisim, O., Akbulut, M., Kwon, Y. B., Kang, H.-M., & Mansoor, S. (2026). A Comprehensive Review of Biochemical Insights and Advanced Packaging Technologies for Shelf-Life Enhancement of Temperate Fruits. Biosensors, 16(2), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020094