A Deep-Learning-Enhanced Ultrasonic Biosensing System for Artifact Suppression in Sow Pregnancy Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section: System and Principles

2.1. The Ultrasonic Biosensing System: An Overview

2.2. Principles of the Ultrasonic Biosensor

2.3. Biosensor Hardware: Mechanical Sector-Scanning Probe

2.4. Sources of Artifacts and the Need for AI Enhancement

3. AI Algorithm for Biosensor Signal Enhancement

3.1. Dataset Construction and Enhancement for Robust Training

3.2. YOLOv8 DNN Architecture for Intelligent Processing

- (1)

- Backbone (Feature Extractor): Based on a modified CSPDarknet, it uses C2f modules (replacing the older C3 modules) to capture rich multi-scale features from the input image. The C2f module employs cross-stage partial connections for efficient gradient flow and feature reuse. A Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) layer at the end aggregates multi-scale contextual information without significant speed loss.

- (2)

- Neck (Feature Aggregator): Employs a Path Aggregation Network combined with a Feature Pyramid Network (PAN-FPN). This structure effectively combines high-resolution, low-level features (rich in spatial details like edges) with low-resolution, high-level features (rich in semantic meaning). This multi-scale fusion is crucial for detecting small, low-contrast targets like early gestational sacs.

- (3)

- Head (Predictor): Uses a decoupled design, separating the tasks of classification (what is the object? “Gestational sac” (for example)) and regression (where is the object? bounding box coordinates). This separation leads to more accurate localization and classification compared to coupled heads.

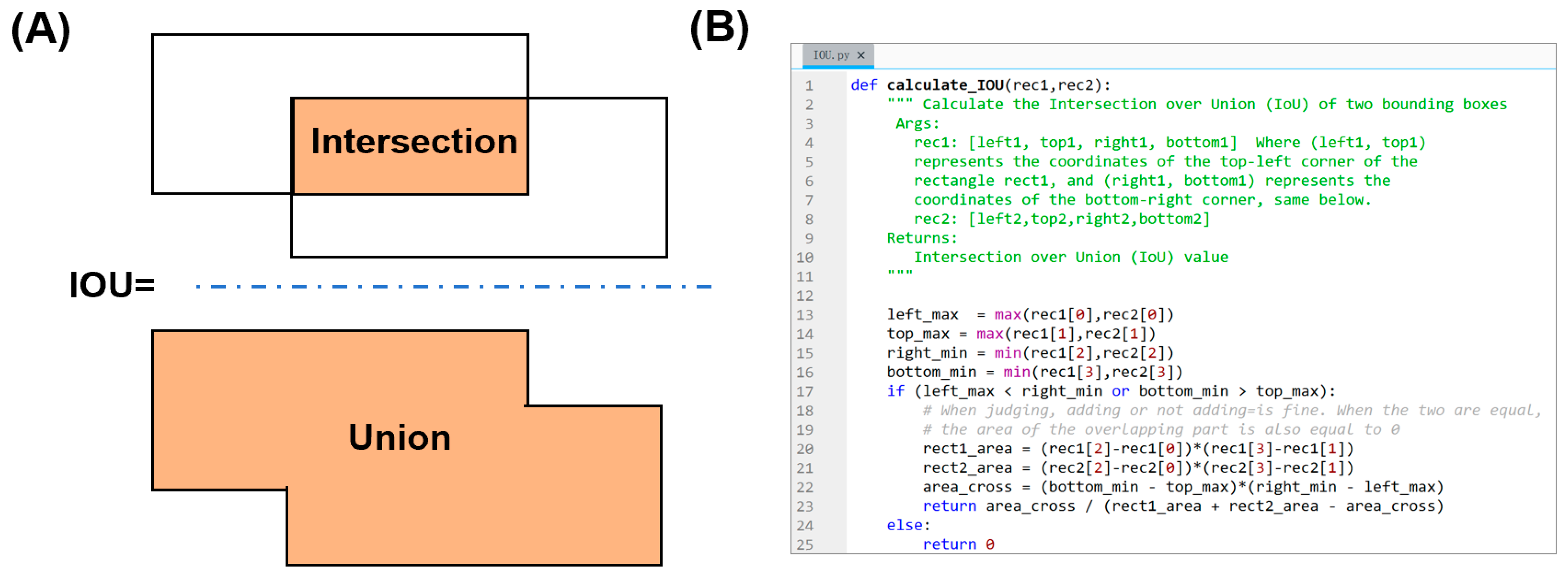

3.3. Error Analysis and Evaluation of Image Enhancement

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Performance Comparison: AI vs. Traditional Methods

4.2. Real-Time Processing Capability

4.3. Training Dynamics and Model Confidence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferraz, P.A.; Poit, D.A.; Pinto, L.M.F.; Guerra, A.C.; Neto, A.L.; do Prado, F.L.; Azrak, A.J.; Çakmakçı, C.; Baruselli, P.S.; Pugliesi, G.; et al. Accuracy of early pregnancy diagnosis and determining pregnancy loss using different biomarkers and machine learning applications in dairy cattle. Theriogenology 2024, 224, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, H.-J.; Jeong, Y.-D.; Cho, E.-S.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, T.-K.; Sa, S.-J.; Cho, H.-C. An intelligent method for pregnancy diagnosis in breeding sows according to ultrasonography algorithms. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2023, 65, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokuldas, P.P.; Shinde, K.R.; Naik, S.; Sahu, A.R.; Singh, S.K.; Chakurkar, E.B. Assessment of diagnostic accuracy and effectiveness of trans-abdominal real-time ultrasound imaging for pregnancy diagnosis in breeding sows under intensive management. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaffas, A.E.; Vo-Phamhi, J.M.; Griffin, I.V.J.F.; Hoyt, K. Critical advances for democratizing ultrasound diagnostics in human and veterinary medicine. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 26, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, M.; Beshir, M.; Mekonnen, M.; Regassa, M.; Seth, D. Effects and Diagnostic Approach of Ultrasound in Veterinary Practice: A Systematic Review. Open Access J. Vet. Sci. Res. 2025, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.M. Basic principles of ultrasound. In Physics for Medical Imaging Applications; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, N.; Ewing, B.S., III. Principles of ultrasound application in animals. Vet. Radiol. 1981, 22, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremkau, F.W.; Taylor, K.J. Artifacts in ultrasound imaging. J. Ultrasound Med. 1986, 5, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baad, M.; Lu, Z.F.; Reiser, I.; Paushter, D. Clinical significance of US artifacts. Radiographics 2017, 37, 1408–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudon, M.; Bergès, O. Artifacts in Ultrasound. In Echography of the Eye and Orbit; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hudhud, G.; Turner, M.J. Digital removal of power frequency artifacts using a Fourier space median filter. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2005, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qin, K.; Zakari, R.Y.; Lu, G.; Yin, J. Deep neural network-based relation extraction: An overview. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 4781–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Alam, M.S.B.; Hassan, M.; Rozbu, M.R.; Ishtiak, T.; Rafa, N.; Mofijur, M.; Ali, A.B.M.S.; Gandomi, A.H. Deep learning modelling techniques: Current progress, applications, advantages, and challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 13521–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Wang, N.; Li, J.; Ding, L. Accurate recognition of jujube tree trunks based on contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization image enhancement and improved YOLOv8. Forests 2024, 15, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. Soft X-ray image recognition and classification of maize seed cracks based on image enhancement and optimized YOLOv8 model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 216, 108475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäberle, W. Fundamental principles. In Ultrasonography in Vascular Diagnosis: A Therapy-Oriented Textbook and Atlas; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Duan, J.; Qi, Q.; Fang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Wu, Y. The Design and Application of Wearable Ultrasound Devices for Detection and Imaging. Biosensors 2025, 15, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, F. Getting the best results from ultrasonography. Practice 2007, 29, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Traditional Methods | AI Model (YOLOv8) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean IoU | 0.65 | 0.89 | +36.9% |

| PSNR (dB) | 28.5 | 34.2 | +20.0% |

| SSIM | 0.72 | 0.92 | +27.8% |

| Early Gestation (1–4 weeks) Accuracy | 76.4% | 98.1% | +21.7% |

| Processing Time (per frame) | >50 ms | 22 ms | >56% faster |

| Artifact Type | IoU (Artifact Region) | PSNR Improvement (dB) | Visual Clarity Score (1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reverberation | 0.91 | +6.2 | 4.7 |

| Acoustic Shadowing | 0.87 | +5.8 | 4.5 |

| Side Lobes | 0.89 | +5.5 | 4.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Luo, X.; Ding, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.; et al. A Deep-Learning-Enhanced Ultrasonic Biosensing System for Artifact Suppression in Sow Pregnancy Diagnosis. Biosensors 2026, 16, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020075

Wang X, Wang J, Gao Z, Luo X, Ding Z, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Yin H, Zhang Y, Liang X, et al. A Deep-Learning-Enhanced Ultrasonic Biosensing System for Artifact Suppression in Sow Pregnancy Diagnosis. Biosensors. 2026; 16(2):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020075

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaoying, Jundong Wang, Ziming Gao, Xinjie Luo, Zitong Ding, Yiyang Chen, Zhe Zhang, Hao Yin, Yifan Zhang, Xuan Liang, and et al. 2026. "A Deep-Learning-Enhanced Ultrasonic Biosensing System for Artifact Suppression in Sow Pregnancy Diagnosis" Biosensors 16, no. 2: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020075

APA StyleWang, X., Wang, J., Gao, Z., Luo, X., Ding, Z., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Yin, H., Zhang, Y., Liang, X., & Ouyang, Q. (2026). A Deep-Learning-Enhanced Ultrasonic Biosensing System for Artifact Suppression in Sow Pregnancy Diagnosis. Biosensors, 16(2), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020075