Two-Dimensional Carbon-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Pesticide Detection: Recent Advances and Environmental Monitoring Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

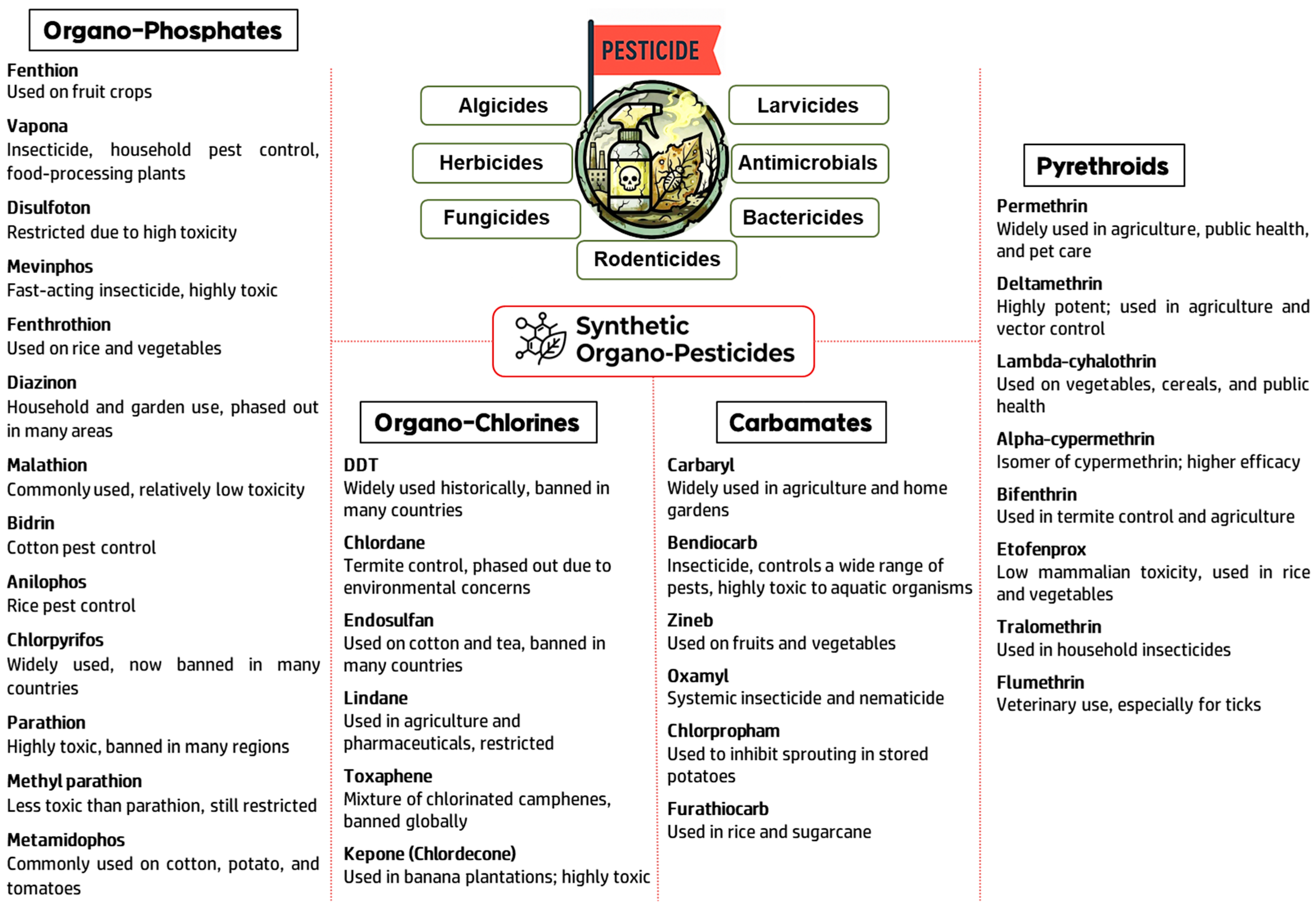

2. Sensor Design Strategies Based on Pesticide Chemical Classes

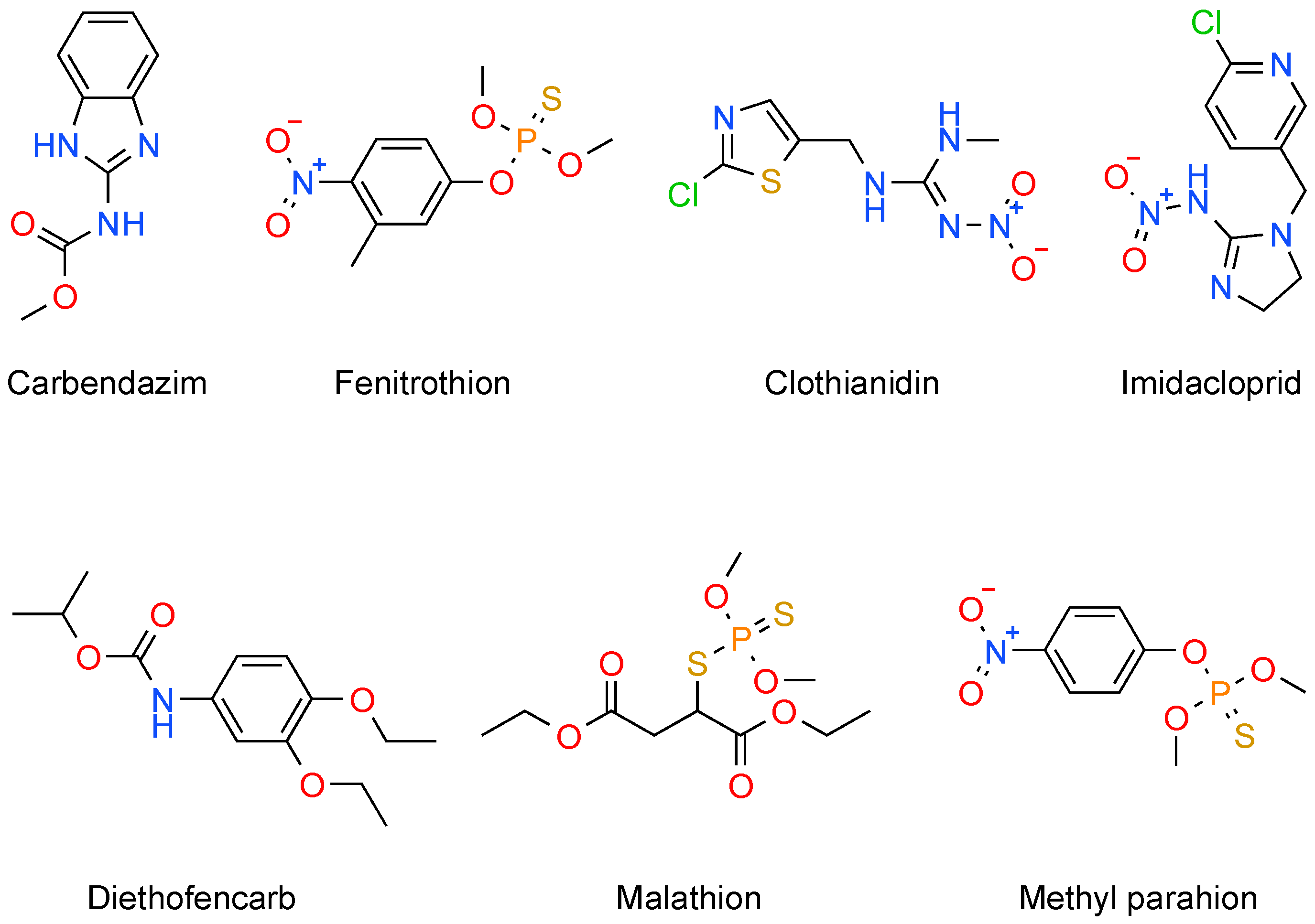

2.1. Organophosphates

2.2. Carbamates

2.3. Organochlorine Pesticides

2.4. Pyrethroid Pesticides

3. Matrix Effect in Electrochemical Detection of Pesticides

4. Overview of 2D Nanomaterials Towards Sensing of Pesticides

4.1. Graphene

4.2. Derivatives of 2D-G

4.3. Graphitic Carbon Nitride

4.4. Graphdiyne

5. Synthesis of 2D Carbon-Based Materials

5.1. The 2D-GO

5.2. The 2D-rGO

5.2.1. Chemical Reduction

5.2.2. Thermal Reduction

5.2.3. Electrochemical Reduction

5.3. Graphdiyne

5.4. The 2D-g-C3N4

6. Synthesis Strategies and Their Influence on Electrochemical Sensing Performance

7. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Detection of Pesticides Using 2D Carbon Materials

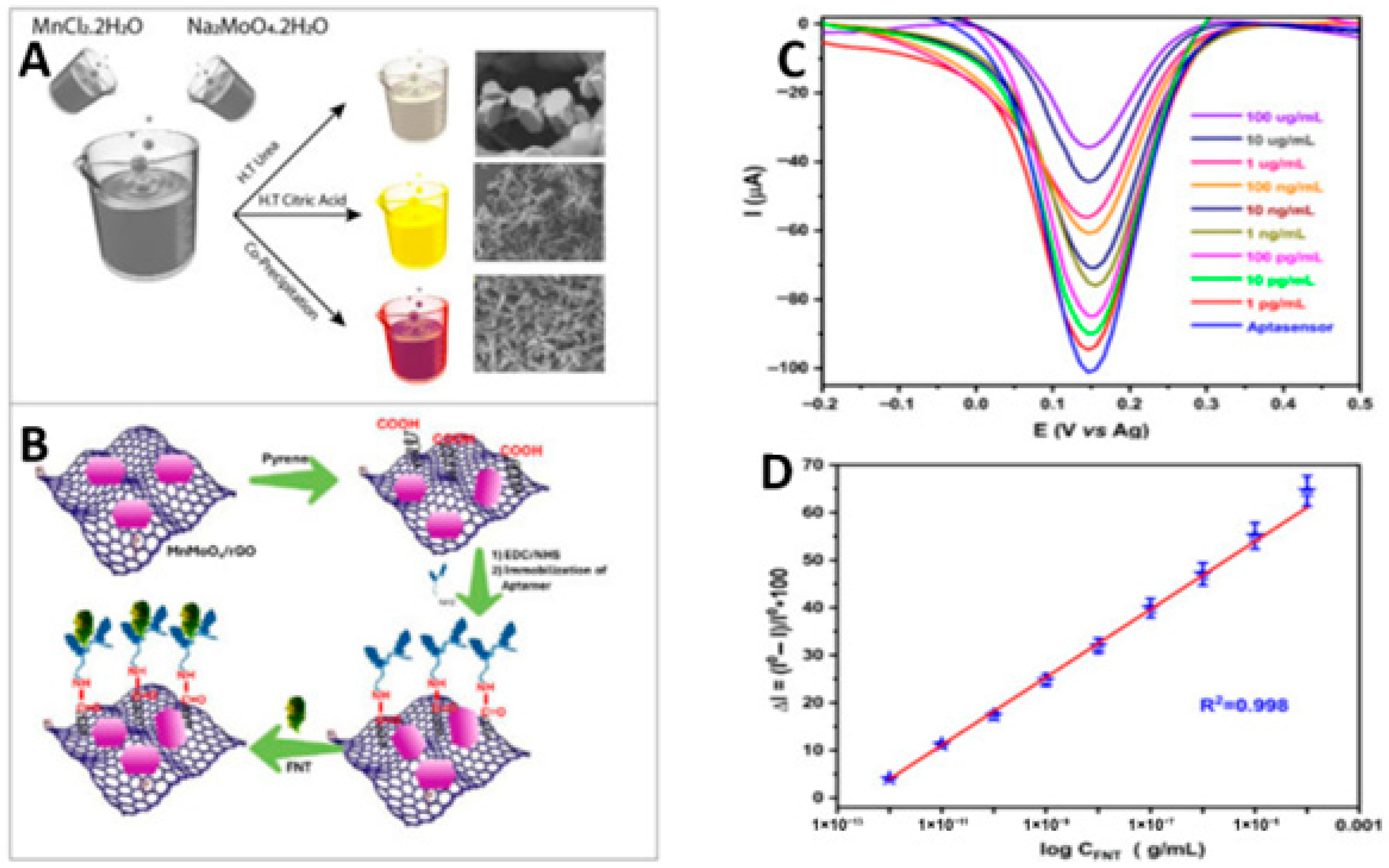

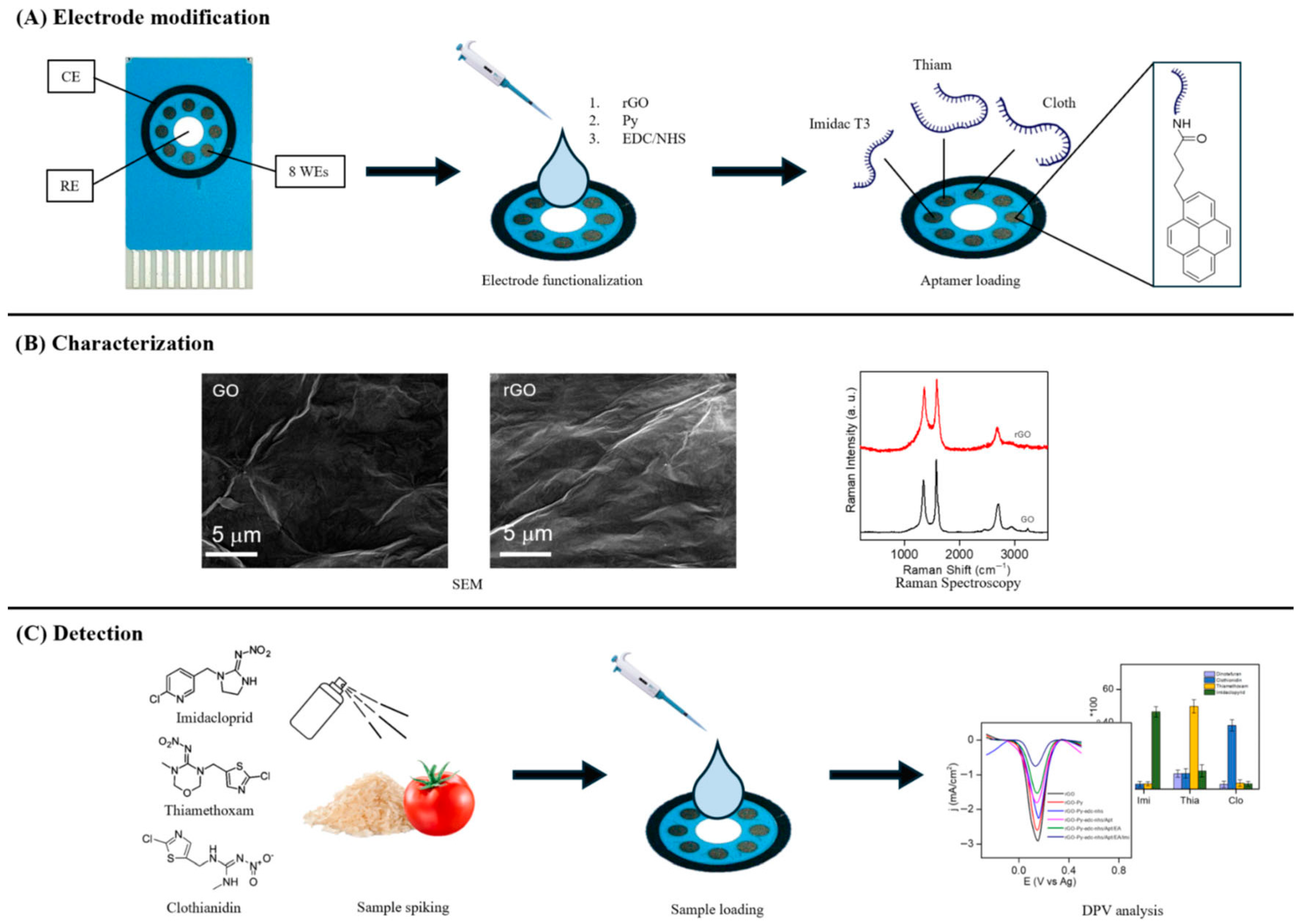

7.1. Two-Dimensional Carbon Derivative Aptamer-Based Sensing

7.2. Two-Dimensional-Carbon Derivatives with Metal Oxide-Based Sensing

7.3. Two-Dimensional-Carbon Derivatives with Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Sensing

7.4. Two-Dimensional-Carbon Derivatives with Enzyme-Based Biosensing

7.5. Structure–Property–Performance Relationships

7.6. Practical Applicability and Outlook

8. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miglione, A.; Raucci, A.; Mancini, M.; Gioia, V.; Frugis, A.; Cinti, S. An electrochemical biosensor for on-glove application: Organophosphorus pesticide detection directly on fruit peels. Talanta 2025, 283, 127093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejigu, A.; Tefera, M.; Guadie, A. Electrochemical detection of pesticides: A comprehensive review on voltammetric determination of malathion, 2,4-D, carbaryl, and glyphosate. Electrochem. Commun. 2024, 169, 107839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, S.; Aftab, S.; Donar, Y.O.; Özoylumlu, B.; Sınağ, A. Waste biomass derived carbon-based materials for electrochemical detection of pesticides from real samples. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 171, 113649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Madhusree, B.; Öztürk, A.A.; Tatsukawa, R.; Miyazaki, N.; Özdamar, E.; Aral, O.; Samsun, O.; Öztürk, B. Persistent organochlorine residues in harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) from the Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1997, 34, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.I.; Thomas, J.; Raju, R.K. Pesticide consumption in India: A spatiotemporal analysis. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Parween, M.; Raju, N.J. Pesticides in the hydrogeo-environment: A review of contaminant prevalence, source and mobilisation in India. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5481–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P, S.; Thasale, R.; Kumar, D.; Mehta, T.G.; Limbachiya, R. Human health risk assessment of pesticide residues in vegetable and fruit samples in Gujarat State, India. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, U.; Puzari, A.; Jamir, T. Toxicological assessment of synthetic pesticides on physiology of Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Pisum sativum L. along with their correlation to health hazards: A case study in south-west Nagaland, India. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2024, 23, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Nian, B.; Yu, C.; Maimaiti, D.; Chai, M.; Yang, X.; Zang, X.; Xu, D. Mechanisms of Neurotoxicity of Organophosphate Pesticides and Their Relation to Neurological Disorders. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024, 20, 2237–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botitsi, H.V.; Garbis, S.D.; Economou, A.; Tsipi, D.F. Current mass spectrometry strategies for the analysis of pesticides and their metabolites in food and water matrices. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2011, 30, 907–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzanese, C.; Lancioni, C.; Castells, C. Gas-liquid chromatography as a tool to determine vapor pressure of low-volatility pesticides: A critical study. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1354, 343932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodova, M.; Nejdl, L.; Pavelicova, K.; Zemankova, K.; Rrypar, T.; Skopalova Sterbova, D.; Bezdekova, J.; Nuchtavorn, N.; Macka, M.; Adam, V.; et al. Detection of pesticides in food products using paper-based devices by UV-induced fluorescence spectroscopy combined with molecularly imprinted polymers. Food Chem. 2022, 380, 132141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskin, E.; Alakus, Z.; Budak, F.; Cetinkaya, A.; Ozkan, S.A. Nanoparticle-supported electrochemical sensors for pesticide analysis in fruit juices. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. Open 2025, 5, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Guo, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Electrochemical sensing mechanisms of neonicotinoid pesticides and recent progress in utilizing functional materials for electrochemical detection platforms. Talanta 2024, 273, 125937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ali, S.; White, R.J. Electrocatalytic Mechanism for Improving Sensitivity and Specificity of Electrochemical Nucleic Acid-Based Sensors with Covalent Redox Tags—Part I. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3833–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, N.; Fan, W.; Cai, H.; Zhao, D. Metal-Organic Framework Based Gas Sensors. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.W.; Silva, M.K.L.; Rascon, J.; Leiva-Tafur, D.; Lapa, R.M.L.; Cesarino, I. Acetylcholinesterase Biosensor Based on Functionalized Renewable Carbon Platform for Detection of Carbaryl in Food. Biosensors 2022, 12, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M.; Solomonenko, A.N.; Barek, J.; Dorozhko, E.V.; Korotkova, E.I.; Aljasar, S.A. Graphene derivatives-based electrodes for the electrochemical determination of carbamate pesticides in food products: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1272, 341449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabelj, T.; Finšgar, M. Recent Progress in Non-Enzymatic Electroanalytical Detection of Pesticides Based on the Use of Functional Nanomaterials as Electrode Modifiers. Biosensors 2022, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, M.; Xiao, M.; Im, M.H.; El-Aty, A.M.A.; Shao, H.; She, Y. Recent Advances in the Recognition Elements of Sensors to Detect Pyrethroids in Food: A Review. Biosensors 2022, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-D.; Li, S.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Du, B.; Shen, Y.-Y.; Yu, B.-Y.; Wang, C.-C. Two bis-ligand-coordinated Zn(ii)-MOFs for luminescent sensing of ions, antibiotics and pesticides in aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 7780–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Qiao, W.; Wu, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Adsorption Behaviors and Mechanism of Phenol and Catechol in Wastewater by Magnetic Graphene Oxides: A Comprehensive Study Based on Adsorption Experiments, Mathematical Models, and Molecular Simulations. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 15101–15113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.J.; Tung, V.C.; Kaner, R.B. Honeycomb Carbon: A Review of Graphene. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Review on the graphene based optical fiber chemical and biological sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 231, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urade, A.R.; Lahiri, I.; Suresh, K.S. Graphene Properties, Synthesis and Applications: A Review. JOM 2023, 75, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Hernandez, F.C.R.; Varghese, O.K.; Jacob, M.V. Plasma-Based Synthesis of Freestanding Graphene from a Natural Resource for Sensing Application. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2202399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Tan, R.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, H.; Chang, G.; He, Y. A novel electrochemical sensor via Zr-based metal organic framework–graphene for pesticide detection. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 19060–19074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadurmus, L.; Cetinkaya, A.; Kaya, S.I.; Ozkan, S.A. Recent trends on electrochemical carbon-based nanosensors for sensitive assay of pesticides. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 34, e00158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Prasad, G.V.; Vinothkumar, V.; Jang, S.J.; Oh, D.E.; Kim, T.H. Reduced Graphene Oxide/β-Cyclodextrin Nanocomposite for the Electrochemical Detection of Nitrofurantoin. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, F. Mechanical properties of graphene oxides. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelikay, G.; Karadurmus, L.; Bilge, S.; Sınağ, A.; Ozkan, S.A. New analytical strategies Amplified with 2D carbon nanomaterials for electrochemical sensing of food pollutants in water and soils sources. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 133974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhsin, S.R. Physical Properties of Graphene. JMechE 2023, 12, 225–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Fal′ko, V.I.; Colombo, L.; Gellert, P.R.; Schwab, M.G.; Kim, K. A roadmap for graphene. Nature 2012, 490, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, M.; Parvez, K.; Nafiujjaman, M.; Revuri, V.; Khan, H.A.; Feng, X.; Lee, Y. Bioapplication of graphene oxide derivatives: Drug/gene delivery, imaging, polymeric modification, toxicology, therapeutics and challenges. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 42141–42161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.; Mitra, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C. Graphene and its sensor-based applications: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 270, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.A.; Waligo, D.; Varghese, O.K.; Jacob, M.V. Advances in graphene-based electrochemical biosensors for on-site pesticide detection. Front. Carbon 2023, 2, 1325970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragumoorthy, C.; Nataraj, N.; Chen, S.-M.; Kiruthiga, G. Yttrium iron oxide embedded reduced graphene oxide: A trace level detection platform for carbamate pesticide in agricultural products. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 196, 106875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherra, N.; Mosbah, A.; Baaziz, H.; Zerriouh, A.; Amusa, H.K.; Darwish, A.S.; Lemaoui, T.; Banat, F.; AlNashef, I.M. Machine learning and quantum-driven multiscale design of graphene-based 2D adsorbents for enhanced aqueous pesticide removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Bai, W.; Deng, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C.; Zheng, S.; Wang, S. Graphene oxide-based dual-color thin-film fluorescent nanolabels for enhanced immunochromatographic detection of pesticides. Anal. Chim. Acta 2025, 1372, 344466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata Prasad, G.; Vinothkumar, V.; Joo Jang, S.; Eun Oh, D.; Hyun Kim, T. Multi-walled carbon nanotube/graphene oxide/poly(threonine) composite electrode for boosting electrochemical detection of paracetamol in biological samples. Microchem. J. 2023, 184, 108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaq, A.; Bibi, F.; Zheng, X.; Papadakis, R.; Jafri, S.H.M.; Li, H. Review on Graphene-, Graphene Oxide-, Reduced Graphene Oxide-Based Flexible Composites: From Fabrication to Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirres, A.C.D.M.; Silva, B.E.P.D.M.D.; Tessaro, L.; Galvan, D.; Andrade, J.C.D.; Aquino, A.; Joshi, N.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors for Pesticide Detection in Foods. Biosensors 2022, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hao, J.; Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mao, H.; Song, X.-M. Layer-by-layer self-assembly film of PEI-reduced graphene oxide composites and cholesterol oxidase for ultrasensitive cholesterol biosensing. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 298, 126856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.V.; Murugesan, A.; Gogoi, R.; Chandrabose, S.; Abass, K.S.; Sharma, V.; Kandhavelu, M. Graphitic carbon nitride nanoparticle: G-C3N4 synthesis, characterization, and its biological activity against glioblastoma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1003, 177999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaddad, E.; Al-fawwaz, A.T.; Rehan, M. An effective stannic oxide/graphitic carbon nitride (SnO2 NPs@g-C3N4) nanocomposite photocatalyst for organic pollutants degradation under visible-light. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2023, 27, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Yan, R.; Dai, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Yang, B.; Yao, Y. Application of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) in solid polymer electrolytes: A mini review. Electrochem. Commun. 2025, 176, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wudil, Y.S.; Ahmad, U.F.; Gondal, M.A.; Al-Osta, M.A.; Almohammedi, A.; Sa’id, R.S.; Hrahsheh, F.; Haruna, K.; Mohamed, M.J.S. Tuning of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) for photocatalysis: A critical review. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basivi, P.K.; Selvaraj, Y.; Perumal, S.; Bojarajan, A.K.; Lin, X.; Girirajan, M.; Kim, C.W.; Sangaraju, S. Graphitic carbon nitride (g–C3N4)–Based Z-scheme photocatalysts: Innovations for energy and environmental applications. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 29, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, M.A.; Javed, M.; Shahid, S.; Shariq, M.; Fadhali, M.M.; Ali, S.K.; Shak, M. Synthesis and applications of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) based membranes for wastewater treatment: A critical review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klini, A.; Kokkotos, S.; Vasilaki, E.; Vamvakaki, M. Graphitic Carbon Nitride (G-C3n4) Optical Sensors for Environmental Monitoring. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, B.; Shahrokhi, M.; Shojaei, F.; Rabczuk, T.; Zhuang, X. A machine learning-assisted exploration of the structural stability, electronic, optical, heat conduction and mechanical properties of C3N4 graphitic carbon nitride monolayers. Comput. Mater. Today 2025, 5, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmadadi, M.; Rahmani, E.; Eshaghi, M.M.; Shamsabadipour, A.; Ghotekar, S.; Rahdar, A.; Romanholo Ferreira, L.F. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) synthesis methods, surface functionalization, and drug delivery applications: A review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 79, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajarajan, S.; Kuchi, C.; Reddy, A.O.; Krishna, K.G.; Kumar, K.S.; Naresh, B.; Sreedhara Reddy, P. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) decorated on CuCo2O4 nanosphere composites for enhanced electrochemical performance for energy storage applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, R.; Nazir, M.S.; Rouf, H.; Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, F.; Ali, Z.; Hassan, S.U. Modified lignin etched sulphur-doped graphitic carbon nitride for electrochemical sensing of cypermethrin in drinking water: Experimental and theoretical insights. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilager, D.; Shetti, N.P.; Foucaud, Y.; Badawi, M.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Graphene/g-carbon nitride (GO/g-C3N4) nanohybrids as a sensor material for the detection of methyl parathion and carbendazim. Chemosphere 2022, 292, 133450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.V.; Rhim, J. Fluorescence Probe for Detection of Malathion Using Sulfur Quantum Dots@Graphitic-Carbon Nitride Nanocomposite. Luminescence 2025, 40, e70112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Kumar, A.; Rachchh, N.; Jyothi, S.R.; Bhanot, D.; Kumari, B.; Kumar, A.; Abosaoda, M.K. Developing a highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for malathion detection based on green g-C3N4 @LiCoO2 nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 3378–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, S.; Abubakar, M.; Farid, M.A.; Zia, R.; Nazir, S.; Razzaque, H.; Ali, A.; Ali, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Al-Masry, W.; et al. Detection of toxic cypermethrin pesticides in drinking water by simple graphitic electrode modified with Kraft lignin@Ni@g-C3 N4 nano-composite. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 9364–9374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Niu, Z.; Rodas-Gonzalez, A.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L. An electrochemical adsorption-catalysis sensor based on 2D MXene/g-C3N4 doped with Au-COOH for selective detection of GMP in meat. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 155893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoh, E.F.; Odey, M.O.; Martin, O.I.; Agurokpon, D.C. In silico engineering of graphitic carbon nitride nanostructures through germanium mono-doping and codoping with transition metals (Ni, Pd, Pt) as sensors for diazinon organophosphorus pesticide pollutants. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, D. Architecture of graphdiyne nanoscale films. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhi, H.V.; Koppad, V.S.; Babu, A.M.; Varghese, A. Properties, Synthesis and Emerging Applications of Graphdiyne: A Journey Through Recent Advancements. Top. Curr. Chem. 2024, 382, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Jin, Z. Application of graphdiyne for promote efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 14, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xue, Y.; Li, Y. 2D graphdiyne, what’s next? Next Mater. 2023, 1, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, B.; Shojaei, F.; Zhuang, X. A first-principles investigation on the structural, stability and mechanical properties of novel Ag, Au and Cu-graphdiyne magnetic semiconducting monolayers. Nano Trends 2023, 4, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, B.; Shahrokhi, M.; Zhuang, X.; Rabczuk, T. Boron–graphdiyne: A superstretchable semiconductor with low thermal conductivity and ultrahigh capacity for Li, Na and Ca ion storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11022–11036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Yi, Y.; Shang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X.; Zhang, S.; Cao, H.; Zhang, G. Nitrogen-doped graphdiyne as a metal-free catalyst for high-performance oxygen reduction reactions. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 11336–11343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, C. Graphdiyne-based nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications. ChemPhysMater 2025, 4, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D. Progress in graphdiyne-based membrane for gas separation and water purification. ChemPhysMater 2025, 4, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Special Issue on “Fundament and Application of 2D Graphdiyne”. ChemPhysMater 2025, 4, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J. Graphdiyne: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 908–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-X.; Fan, Y.-G.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Cheng, X.-Y.; Guo, F.; Wang, Z.-Y. Graphdiyne biomaterials: From characterization to properties and applications. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, A.; Wagh, V.; Chakraborty, B. Enhanced hydrogen storage in graphdiyne through compressive strain: Insights from density functional theory simulations. J. Energy Storage 2025, 117, 116153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhang, S.; Ye, X.; Xuan, Y.; He, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, W. Ultra-sensitive simultaneous electrochemical detection of Zn(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) based on the bismuth and graphdiyne film modified electrode. Microchem. J. 2023, 184, 108186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, F. Nitrogen and fluoride co-doped graphdiyne with metal-organic framework (MOF)-derived NiCo2O4–Co3O4 nanocages as sensing layers for ultra-sensitive pesticide detection. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1252, 341012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, S.; Li, P.; Lin, Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, Y.; Yan, J.; Huang, K.-J.; Tan, X. Self-powered dual-mode sensing strategy based on graphdiyne and DNA nanoring for sensitive detection of tumor biomarker. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 237, 115557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummers, W.S.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano, D.C.; Kosynkin, D.V.; Berlin, J.M.; Sinitskii, A.; Sun, Z.; Slesarev, A.; Alemany, L.B.; Lu, W.; Tour, J.M. Improved Synthesis of Graphene Oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q. Green preparation of graphene oxide nanosheets as adsorbent. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovich, S.; Dikin, D.A.; Piner, R.D.; Kohlhaas, K.A.; Kleinhammes, A.; Jia, Y.; Wu, Y.; Nguyen, S.T.; Ruoff, R.S. Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. Carbon 2007, 45, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.J.; Kim, K.K.; Benayad, A.; Yoon, S.; Park, H.K.; Jung, I.; Jin, M.H.; Jeong, H.; Kim, J.M.; Choi, J.; et al. Efficient Reduction of Graphite Oxide by Sodium Borohydride and Its Effect on Electrical Conductance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 1987–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Merino, M.J.; Guardia, L.; Paredes, J.I.; Villar-Rodil, S.; Solís-Fernández, P.; Martínez-Alonso, A.; Tascón, J.M.D. Vitamin C Is an Ideal Substitute for Hydrazine in the Reduction of Graphene Oxide Suspensions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 6426–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolhosseinzadeh, S.; Asgharzadeh, H.; Seop Kim, H. Fast and fully-scalable synthesis of reduced graphene oxide. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Park, J.; Gou, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Yao, J. Facile Synthesis and Characterization of Graphene Nanosheets. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 8192–8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-S.; Ren, W.; Gao, L.; Liu, B.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, H.-M. Synthesis of high-quality graphene with a pre-determined number of layers. Carbon 2009, 47, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larciprete, R.; Fabris, S.; Sun, T.; Lacovig, P.; Baraldi, A.; Lizzit, S. Dual Path Mechanism in the Thermal Reduction of Graphene Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17315–17321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, I.; Chakraborty, S.; Talukdar, M.; Pal, S.K.; Chakraborty, S. Thermal reduction of graphene oxide: How temperature influences purity. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 4113–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemeyer, L.; Park, H.; Huang, J. Geometry-Dependent Thermal Reduction of Graphene Oxide Solid. ACS Mater. Lett. 2021, 3, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, C.; Montes-García, V.; Livio, P.A.; Chudziak, T.; Raya, J.; Ciesielski, A.; Samorì, P. Tuning the electrical properties of graphene oxide through low-temperature thermal annealing. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 5743–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Yu, G. Synthesis of N-Doped Graphene by Chemical Vapor Deposition and Its Electrical Properties. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 1752–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Cheng, H.-M. The reduction of graphene oxide. Carbon 2012, 50, 3210–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Duan, M.; Li, R.; Meng, Y.; Bai, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Sui, N. Ultrathin Graphdiyne/Graphene Heterostructure as a Robust Electrochemical Sensing Platform. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 13598–13606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Yi, Y. Electroless deposition of platinum on graphdiyne for electrochemical sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, L.; Guo, X. Construction of an electrochemical sensor for the detection of methyl parathion with three-dimensional graphdiyne-carbon nanotubes. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, X.; Wang, D.; Zhu, L.; Ha-Thi, M.; Pino, T.; Arbiol, J.; Wu, L.; Nawfal Ghazzal, M. A Deprotection-free Method for High-yield Synthesis of Graphdiyne Powder with In Situ Formed CuO Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202210242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xiao, P.; Li, H.; Carabineiro, S.A.C. Graphitic Carbon Nitride: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications in Catalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 16449–16465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.; Fischer, A.; Goettmann, F.; Antonietti, M.; Müller, J.-O.; Schlögl, R.; Carlsson, J.M. Graphitic carbon nitride materials: Variation of structure and morphology and their use as metal-free catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, H.-T.; Wang, X.; Xue, B.; Li, Y.-X.; Cao, Y. A new and environmentally benign precursor for the synthesis of mesoporous g-C3N4 with tunable surface area. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Wu, L.; Sun, Y.; Fu, M.; Wu, Z.; Lee, S.C. Efficient synthesis of polymeric g-C3N4 layered materials as novel efficient visible light driven photocatalysts. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 15171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Fu, X.; Antonietti, M.; Wang, X. Fe-g-C3N4 -Catalyzed Oxidation of Benzene to Phenol Using Hydrogen Peroxide and Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11658–11659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, M.-Q.; Bao, S.-J.; Lu, S.; Xu, M.; Long, D.; Pu, S. Tuning and thermal exfoliation graphene-like carbon nitride nanosheets for superior photocatalytic activity. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18521–18528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abega, A.V.; Marchal, C.; Dziurla, M.-A.; Dantio, N.C.B.; Robert, D. Easy three steps gC3N4 exfoliation for excellent photocatalytic activity—An in-depth comparison with conventional approaches. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 304, 127803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.V.; Elkaffas, R.A.; Eissa, S. Unleashing the power of MnMoO4/rGO nanocomposite towards the electrochemical aptasensing of neurotoxic pesticide fenitrothion. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 536, 146708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenhali, A.Z.; Kanagavalli, P.; Abd-Ellah, M.; Khazaal, S.; El Darra, N.; Eissa, S. Reduced graphene oxide-based electrochemical aptasensor for the multiplexed detection of imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin in food samples. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariyappan, V.; Sundaresan, R.; Chen, S.-M.; Ramachandran, R.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Jeevika, A.; Wu, W. Constructing a novel electrochemical sensor for the detection of fenitrothion using rare-earth orthophosphate incorporated reduced graphene oxide composite. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 185, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radha, A.; Wang, S.-F. Construction of calcium zirconate nanoparticles confined on graphitic carbon nitride: An electrochemical detection of diethofencarb in food samples. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 141929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, W.S.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, A.; Thakur, S.; Mehta, S.K.; Raja, V.; Ataya, F.S. Non-enzymatic g-C3N4 supported CuO derived-biochar based electrochemical sensors for trace level detection of malathion. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 267, 116808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurđić, S.; Vlahović, F.; Ognjanović, M.; Gemeiner, P.; Sarakhman, O.; Stanković, V.; Mutić, J.; Stanković, D.; Švorc, Ľ. Nano-size cobalt-doped cerium oxide particles embedded into graphitic carbon nitride for enhanced electrochemical sensing of insecticide fenitrothion in environmental samples: An experimental study with the theoretical elucidation of redox events. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 909, 168483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yola, M.L. Carbendazim imprinted electrochemical sensor based on CdMoO4/g-C3N4 nanocomposite: Application to fruit juice samples. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, A.H.; Abd-Rabboh, H.S.M. Imprinted polymer/reduced graphene oxide-modified glassy carbon electrode-based highly sensitive potentiometric sensing module for imidacloprid detection. Microchem. J. 2024, 197, 109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Ding, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, B. A Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Methamidophos Immobilized AChE Biosensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides Detection. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, S.; Nasir, M.; Hassan, M.M.; Rehman, M.F.U.; Sami, A.J.; Hayat, A. A novel construct of an electrochemical acetylcholinesterase biosensor for the investigation of malathion sensitivity to three different insect species using a NiCr2 O4/g-C3 N4 composite integrated pencil graphite electrode. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 16860–16874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shang, D.; Gao, S.; Wang, B.; Kong, H.; Yang, G.; Shu, W.; Xu, P.; Wei, G. Two-Dimensional Material-Based Electrochemical Sensors/Biosensors for Food Safety and Biomolecular Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, C.J.; Bollo, S.; Sierra-Rosales, P. Carbon-Based Electrochemical (Bio)sensors for the Detection of Carbendazim: A Review. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarević-Pašti, T. Carbon Materials for Organophosphate Pesticide Sensing. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehru, R.; Hsu, Y.-F.; Wang, S.-F.; Dong, C.-D.; Govindasamy, M.; Habila, M.A.; AlMasoud, N. Graphene oxide@Ce-doped TiO2 nanoparticles as electrocatalyst materials for voltammetric detection of hazardous methyl parathion. Microchim. Acta 2021, 188, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B. Electrochemical sensor based on Bimetallic phosphosulfide Zn–Ni–P–S Nanocomposite -reduced graphene oxide for determination of Paraoxon Ethyl in agriculture wastewater. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2022, 17, 220672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weheabby, S.; Liu, Z.; Pašti, I.A.; Rajić, V.; Vidotti, M.; Kanoun, O. Enhanced electrochemical sensing of methyl parathion using AgNPs@IL/GO nanocomposites in aqueous matrices. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 2195–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Luo, S.; Liu, X.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C. Ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of methyl parathion pesticide based on cationic water-soluble pillar[5]arene and reduced graphene nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceylan, E.; Ozoglu, O.; Huseyin Ipekci, H.; Tor, A.; Uzunoglu, A. Non-enzymatic detection of methyl parathion in water using CeO2-CuO-decorated reduced graphene oxide. Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, A.; Kumarswamy, Y.K.; Prashanth, M.K.; Hamzada, S.; Lakshminarayana, P.; Pradeep Kumar, C.B.; Jeon, B.-H.; Raghu, M.S. Fabrication of FeVO4/RGO Nanocomposite: An Amperometric Probe for Sensitive Detection of Methyl Parathion in Green Beans and Solar Light-Induced Degradation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 45239–45252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Rana, S.; Kaur, K.; Navodita. Ultra-sensitive detection of methylparathion using palladium nanoparticles embedded reduced graphene oxide redox nanoreactors. Microchem. J. 2023, 191, 108871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, R.; Manavalan, S.; Chen, S.-M.; Keerthi, M.; Lin, L.-H. Methyl Parathion Detection Using SnS2/N, S–Co-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 11194–11203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, K.; Li, J.; Yin, Y.; Zuo, J. A novel electrochemical sensor based on NiO/MoS2/rGO composite material for rapid detection of methyl parathion. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G. Hierarchical nitrogen-doped holey graphene as sensitive electrochemical sensor for methyl parathion detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 336, 129721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayem, N.I.; Hossain, M.S.; Rashed, M.A.; Anis-Ul-Haque, K.M.; Ahmed, J.; Faisal, M.; Algethami, J.S.; Harraz, F.A. A sensitive and selective electrochemical detection and kinetic analysis of methyl parathion using Au nanoparticle-decorated rGO/CuO ternary nanocomposite. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15348–15365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weheabby, S.; You, S.; Pašti, I.A.; Al-Hamry, A.; Kanoun, O. Direct electrochemical detection of pirimicarb using graphene oxide and ionic liquid composite modified by gold nanoparticles. Measurement 2024, 236, 115132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, M.; He, H.; Gao, N.; Cai, Z.; Chang, G.; He, Y. Novel graphene electrochemical transistor with ZrO2/rGO nanocomposites functionalized gate electrode for ultrasensitive recognition of methyl parathion. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 328, 128936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, Z.; Fatima, N.; Anjum, S.; Qureshi, N.; Khan, M.I.; Shanableh, A.; Ahmad, F.; Qureshi, H.O.A.; Luque, R. Efficient CeO2/NiO/GO nanocomposites for the detection of toxic carbofuran pesticide in real samples. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna, M.V.S.S.; Carvalho, S.W.M.M.; Gevaerd, A.; Silva, J.O.S.; Santos, E.; Carregosa, I.S.C.; Wisniewski, A.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F.; Sussuchi, E.M. Electrochemical sensor based on biochar and reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for carbendazim determination. Talanta 2020, 220, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Nesakumar, N.; Rayappan, J.B.B.; Kulandaiswamy, A.J. Electrochemical Detection of Imidacloprid Using Cu–rGO Composite Nanofibers Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 104, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Pang, C.; Ma, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhi, X.; Li, B. Electrochemical sensor for imidacloprid detection based on graphene oxide/gold nano/β-cyclodextrin multiple amplification strategy. Microchem. J. 2022, 183, 107979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhe, T.; Bai, Y.; Bu, T.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L. Electrochemical behavior of reduced graphene oxide/cyclodextrins sensors for ultrasensitive detection of imidacloprid in brown rice. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, M.R.; Ghaderi, S. Facile fabrication and characterization of silver nanodendrimers supported by graphene nanosheets: A sensor for sensitive electrochemical determination of Imidacloprid. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 792, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, S.A.; Ferreira, O.A.E.; César, P.A. Determination of Imidacloprid Based on the Development of a Glassy Carbon Electrode Modified with Reduced Graphene Oxide and Manganese (II) Phthalocyanine. Electroanalysis 2020, 32, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimalai, D.; Putnin, T.; Bamrungsap, S. A highly sensitive electrochemical sensor based on poly(3-aminobenzoic acid)/graphene oxide-gold nanoparticles modified screen printed carbon electrode for paraquat detection. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 148, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yassin, J.M.; Taddesse, A.M.; Tsegaye, A.A.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M. CdS/g-C3N4/Sm-BDC MOF nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrodes as a highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for malathion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 648, 158973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Rajput, J.K. A prompt electrochemical monitoring platform for sensitive and selective determination of thiamethoxam using Fe2O3@g-C3N4@MSB composite modified glassy carbon electrode. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, M.M.; Kalanur, S.S.; Pandiaraj, S.; Alodhayb, A.N.; Pollet, B.G.; Shetti, N.P. Synthesis of graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) by high-temperature condensation for electrochemical evaluation of dichlorophen and thymol in environmental trials. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 50, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthinathan, S.; Keyan, A.K.; Vasu, D.; Vinothini, S.; Nagaraj, K.; Mangesh, V.L.; Chiu, T.-W. Graphitic Carbon Nitride Incorporated Europium Molybdate Composite as an Enhanced Sensing Platform for Electrochemical Detection of Carbendazim in Agricultural Products. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 127504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, B.; Achary, L.S.K.; Barik, B.; Jyotsna Sahoo, S.; Mohanty, A.; Dash, P. MnCo2O4 decorated (2D/2D) rGO/g-C3N4-based Non-Enzymatic sensor for highly selective and sensitive detection of Chlorpyrifos in water and food samples. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 909, 116115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, I.; Meribai, A.; Çakar, S.; Ünlü, B.; Özacar, M.; Bessekhouad, Y. Non-enzymatic electrochemical sensor for selective detection of glyphosate in real water samples using SrxZn1−xO/g-C3N4 composite electrode. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 344, 131159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Meng, J.; Li, W.; Gu, K. Investigating the sensitivity and selectivity of electrochemical sensors based on nanomaterials for the detection of carbendazim residue in cherry wine. Food Meas. 2024, 18, 5376–5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, S.; Rajput, J.K. Ultrasensitive electrochemical sensor for nitroaromatics using C3N4-MoS2-Au nanocomposite with pendimethalin as a real sample. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Li, H.; Yan, X.; Yan, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Qian, C.; Wang, Y. Graphitic carbon nitride/graphene oxide(g-C3N4/GO) nanocomposites covalently linked with ferrocene containing dendrimer for ultrasensitive detection of pesticide. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1103, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2D-Carbon with Composite | Targeted Pesticide/Class | Method | LOD | Linear Range | Real Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO@Ce-doped TiO2 | methyl parathion | DPV | 0.0016 μM | 0.002–48.327 μM | apple and tomato | [116] |

| Zn-Ni-P-S/GO/GCE | paraoxon ethyl | AMP | 0.035 μM | 1–200 μM | agriculture wastewater | [117] |

| AgNPs@GO/IL@SPCE | methyl parathion | SWV | 9 μM | 25–200,000 μM | ground water and surface water | [118] |

| CP5-rGO/GCE | methyl parathion | DPV | 0.0003 μM | 0.001–150 μM | soil and tap water | [119] |

| CeO2-CuO/rGO | methyl parathion | DPV | 0.00179 μM | 0.0038–0.152 μM | mineral, drinking, and tap water samples | [120] |

| FeVO4/RGO | methyl parathion | AMP | 0.00070 μM | 0.001–20 μM | green beans | [121] |

| RGO-CHI | parathion dichlorvos methamidophos trichlorfon dimethoate fenthion methomyl chlorpyrifos omethoate diazinon | DPV | 0.05–0.52 ng mL−1 | 0–1500 ng mL−1 | NA | [111] |

| Pd@NrGO | methyl parathion | SWASV | 1.067 ng mL−1 122 ng mL−1 | 1.8–10 ng mL−1 50–1000 ng mL−1 | river water, onion, agricultural run-off, cabbage, lettuce leaves and tap water | [122] |

| SnS2/NS-RGO | methyl parathion | CV | 0.00017 μM | 0.001–176 μM | xindian river and black grapes | [123] |

| YFO-rGO/RDE | carbofuran | i-t | 0.018 μM | 0.029–303.5 μM | carrots, cucumber, cabbage, spinach, tomato and potato. | [37] |

| NiO/MoS2/Rgo | methyl parathion | DPV | 1.1 ng mL−1 | 10–10,000 ng mL−1 | apple juice | [124] |

| N-HG50/GCE | methyl parathion | DPV | 0.013 nM | 1 ng mL–150 μg mL−1 | apple, grape, cucumber and river water | [125] |

| Au@rGO/CuO/GCE | methyl parathion | SWV | 0.045 μM | 0.4–39.0 μM | Dhaleswari river | [126] |

| AuNPs@GO/IL@SPCE | pirimicarb | SWV | 4.49 μM | 50–1500 μM | groundwater and surface water | [127] |

| ZrO2/rGO | methyl parathion | GECT | 10 pg mL−1 | 1 × 10−5–10 μg L−1 | Chinese cabbages | [128] |

| CeO2/NiO/GO | carbofuran | DPV | 0.82 μM | 5–150 μM | potato | [129] |

| CPE-rGO | carbofuran | DPV | 0.0023 μM | 0.03–0.8 μM | drinking water, lettuce leaves, orange juice, wastewater | [130] |

| Cu-rGO | imidacloprid | CV | 0.003247 μM | NA | soil sample from paddy field | [131] |

| GO/Au NPs/β-CD | imidacloprid | DPV | 0.000133 μM | 5 × 10−4–0.3 μM | Chinese cabbage, banana and mango | [132] |

| GCE/rGO/MIP | imidacloprid | Potentiometry | 0.8 μM | 1–1000 μM | NA | [110] |

| E-rGO/CDs | imidacloprid | CV | 0.02 μM | 0.5–40 μM | brown rice | [133] |

| AgNDs/GNs/GCE | imidacloprid | DPV | 0.814 μM | 1–100 μM | cucumber | [134] |

| GCE/rGO/MnPc | imidacloprid | CV | 6.5 μM | 25–250 μM | honey | [135] |

| SPCE/GO/AuNPs/P3ABA | paraquat | SWV | 4.5 × 10−4 μM | 0.001–100 μM | tap water and natural water | [136] |

| MnMoO4/rGO | fenitrothion | DPV | 3.0 × 10−4 ng mL−1 | 1.00 × 10−3–1.00 × 105 ng mL−1 | wastewater and rice extract | {103] |

| GdPO4/RGO | fenitrothion | DPV | 0.007 μM | 0.01–342 μM | river and tap water | [105] |

| rGO-aptamer | imidacloprid thiamethoxam clothianidin | DPV | 6.30 pg mL−1 6.80 pg mL−1 7.10 pg mL−1 | 0.01–100 ng mL−1 | rice and tomato water | [104] |

| 2D-Carbon with Composite | Targeted Pesticide/Class | Method | LOD | Linear Range | Real Sample | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KL@Ni@g-C3N4 | Cypermethrin | CV | 0.026 μg mL−1 | 0.05–0.2 μg mL−1 | Tap Water | [58] |

| g-C3N4@LiCoO2 | Malathion | DPV | 0.00438 μM | 0.005–0.12 μM | Lettuce | [57] |

| GO/g-C3N4 | Methyl parathion carbendazim | SWV | 8.4 × 10−4 μM 2.0 × 10−6 μM | 0.08–100 μM 0.01–250 μM | Water and Soil sample | [55] |

| CdS/g-C3N4/Sm-BDC | Malathion | DPV | 0.0074 μM | 0.03–0.15 µM | Cabbage | [137] |

| B-CuO/g-C3N4 | Malathion | SWASV | 1.2 pg mL−1 | 0.18–5.66 pg mL−1 | Soil, Rice, Water and Fruits | [107] |

| g-C3N4@Co-doped CeO2 | Fenitrothion | SWV | 0.0032 μM | 0.01–13.70 μM | Tap water and Ethanolic apple extract | [108] |

| CaZrO3@g-C3N4 | Diethofencarb | DPV | 0.0018 μM | 0.01–230.04 µM | Strawberry, Grapes, Spinach, and Apple | [106] |

| MIP/CdMoO4/g- C3N4 | Carbendazim | CV | 2.5 × 10−6 µM | 1.0 × 10−5–1.0 × 10−3 µM | Fruit juice | [109] |

| Fe2O3@g-C3N4 @MSB | Thiamethoxam | LSV | 0.137 µM | 0.01–200 µM | Potato, Rice and River water | [138] |

| g-C3N4/CPE | Dichlorophen Thymol | SWV | 0.012 µM | 0.05–100 µM | Soil and Water | [139] |

| g-C3N4/EuMoO4 | Carbendazim | DPV | 0.04 µM | 50–400 µM | Apple and Tomato | [140] |

| rGO-g-C3N4-MnCo2O4 | Chlorpyrifos | DPV | 0.32 × 10−6 μg mL−1 | 1.5 × 10−5–7.0 µg mL−1 | Groundwater, Tap water and Pomegranate sample | [141] |

| KL@Ni@S-g-C3N4 | Cypermethrin | CV | 0.05 µg mL−1 | 0.1–1.0 µg mL−1 | Tap water | [54] |

| NiCr2O4/g-C3N4 | Malathion | CV | 0.0023 µM | 0.002–0.10 µM | Wheat flour | [112] |

| SrxZn1-xO/g-C3N4 | Glyphosate | DPV | 1.4 × 10−4 µM | 0.002–0.1 µM | Lake Sapanca, Tap water and Natural Spring water. | [142] |

| PTH-g-C3N4 | Carbendazim | DPV | 3.7 × 10−4 µM | 0.1–85 µM | Cherry Wine | [143] |

| C3N4-MoS2-Au | Pendimethalin | LSV | 0.219 µM 0.615 µM 0.479 µM | 0–1000 µM 0–500 µM 0–500 µM | Tap water and Distilled water | [144] |

| g-C3N4/GO/Fc-TED | Metolcarb | DPV | 0.0083 µM | 0.045–213 µM | Vegetable Spinach | [145] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Imran, K.; Amin, A.; Venkata Prasad, G.; Veera Manohara Reddy, Y.; Gita, L.I.; Wilson, J.; Kim, T.H. Two-Dimensional Carbon-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Pesticide Detection: Recent Advances and Environmental Monitoring Applications. Biosensors 2026, 16, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010062

Imran K, Amin A, Venkata Prasad G, Veera Manohara Reddy Y, Gita LI, Wilson J, Kim TH. Two-Dimensional Carbon-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Pesticide Detection: Recent Advances and Environmental Monitoring Applications. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleImran, K., Al Amin, Gajapaneni Venkata Prasad, Y. Veera Manohara Reddy, Lestari Intan Gita, Jeyaraj Wilson, and Tae Hyun Kim. 2026. "Two-Dimensional Carbon-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Pesticide Detection: Recent Advances and Environmental Monitoring Applications" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010062

APA StyleImran, K., Amin, A., Venkata Prasad, G., Veera Manohara Reddy, Y., Gita, L. I., Wilson, J., & Kim, T. H. (2026). Two-Dimensional Carbon-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Pesticide Detection: Recent Advances and Environmental Monitoring Applications. Biosensors, 16(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010062