An Improved Dengue Virus Serotype-Specific Non-Structural Protein 1 Capture Immunochromatography Method with Reduced Sample Volume

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Immunochromatographic Assay Preparation

2.3. Viruses

2.4. Sequence Determination of DENV Strains

2.5. Clinical Specimens in Thailand

2.6. Clinical Specimens in Patients in Japan

2.7. Antigen Detection Using the IC Devices

3. Results

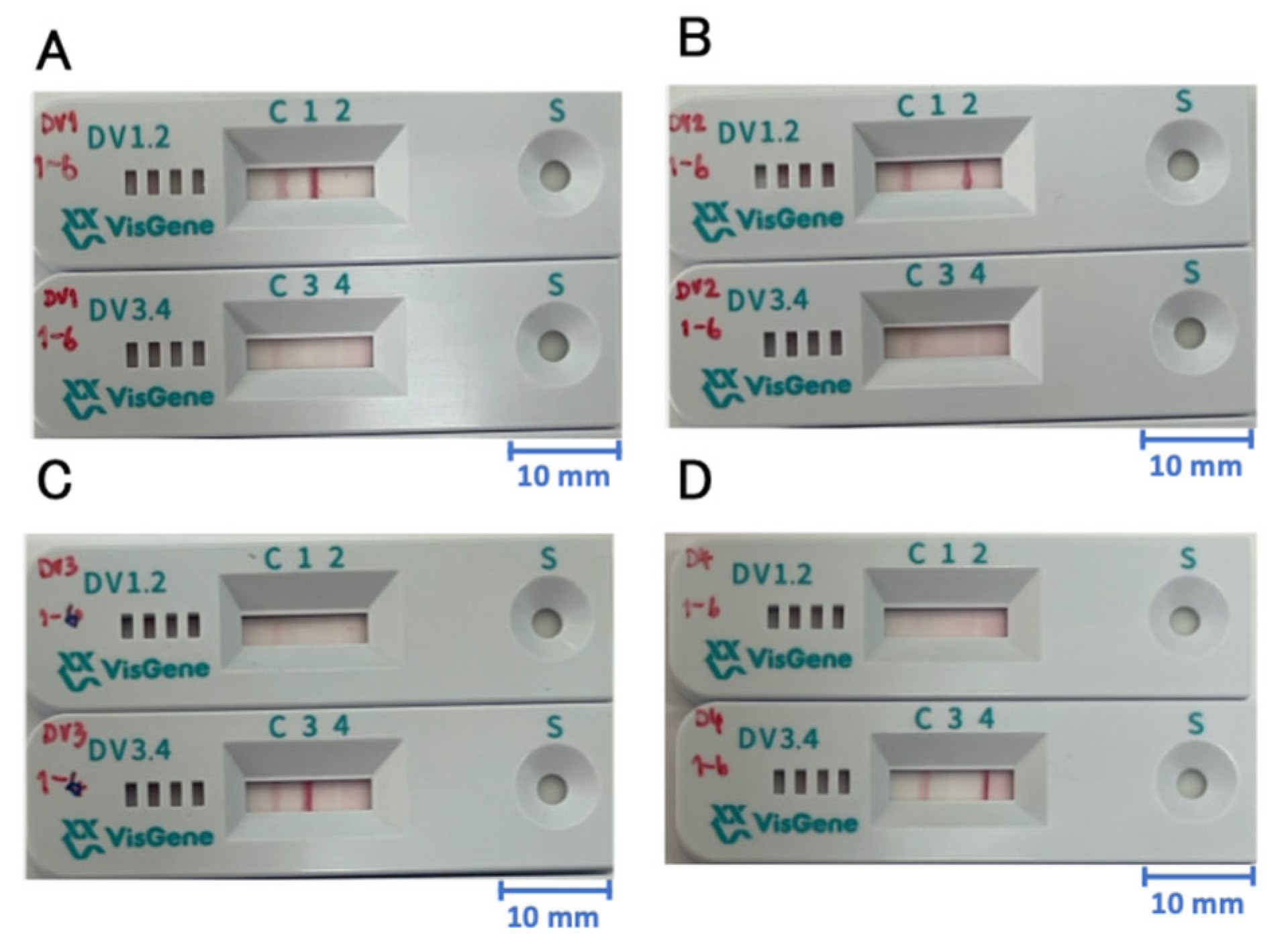

3.1. Reconstruction of a DENV Serotype-Specific NS1 Capture IC Kit

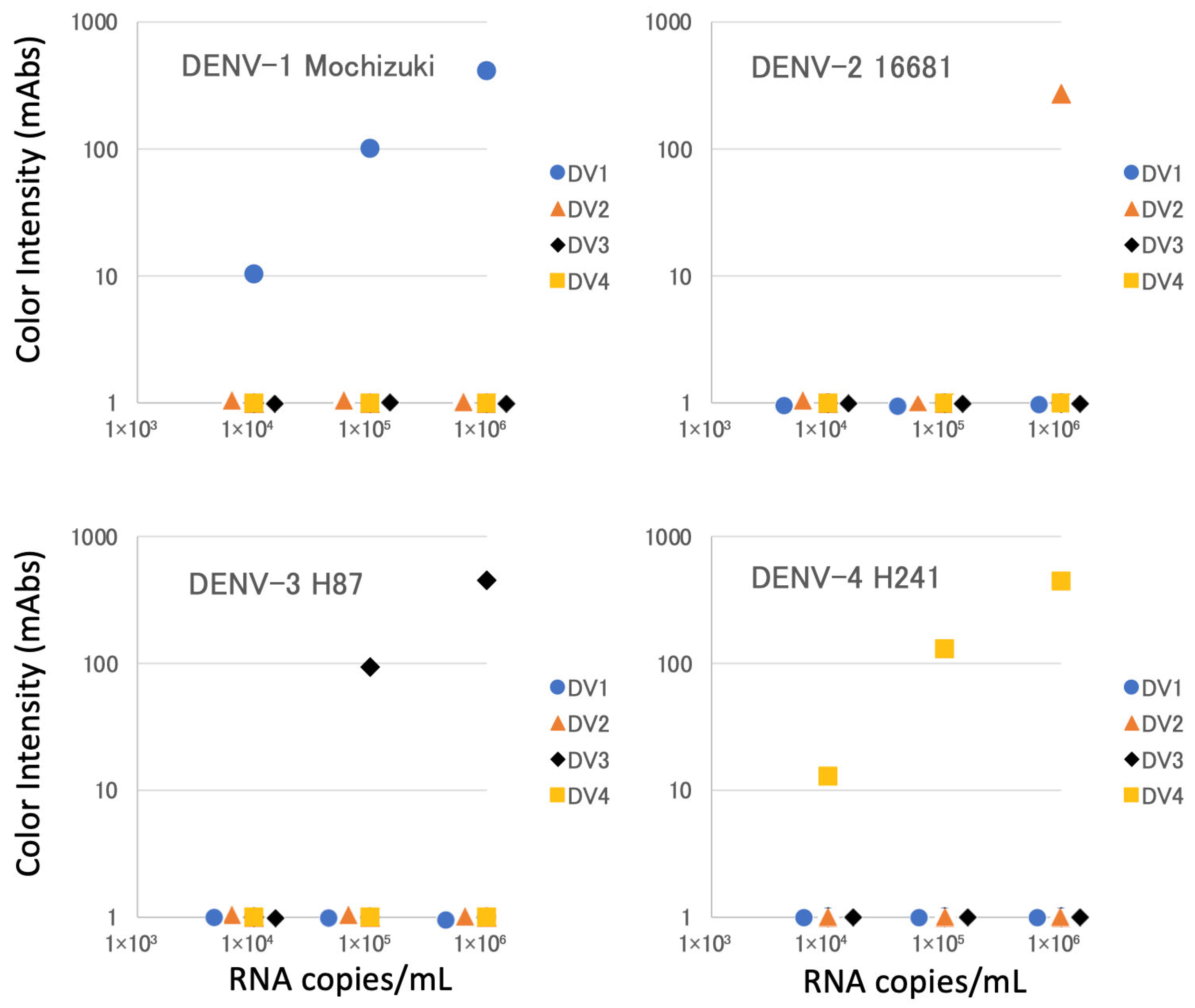

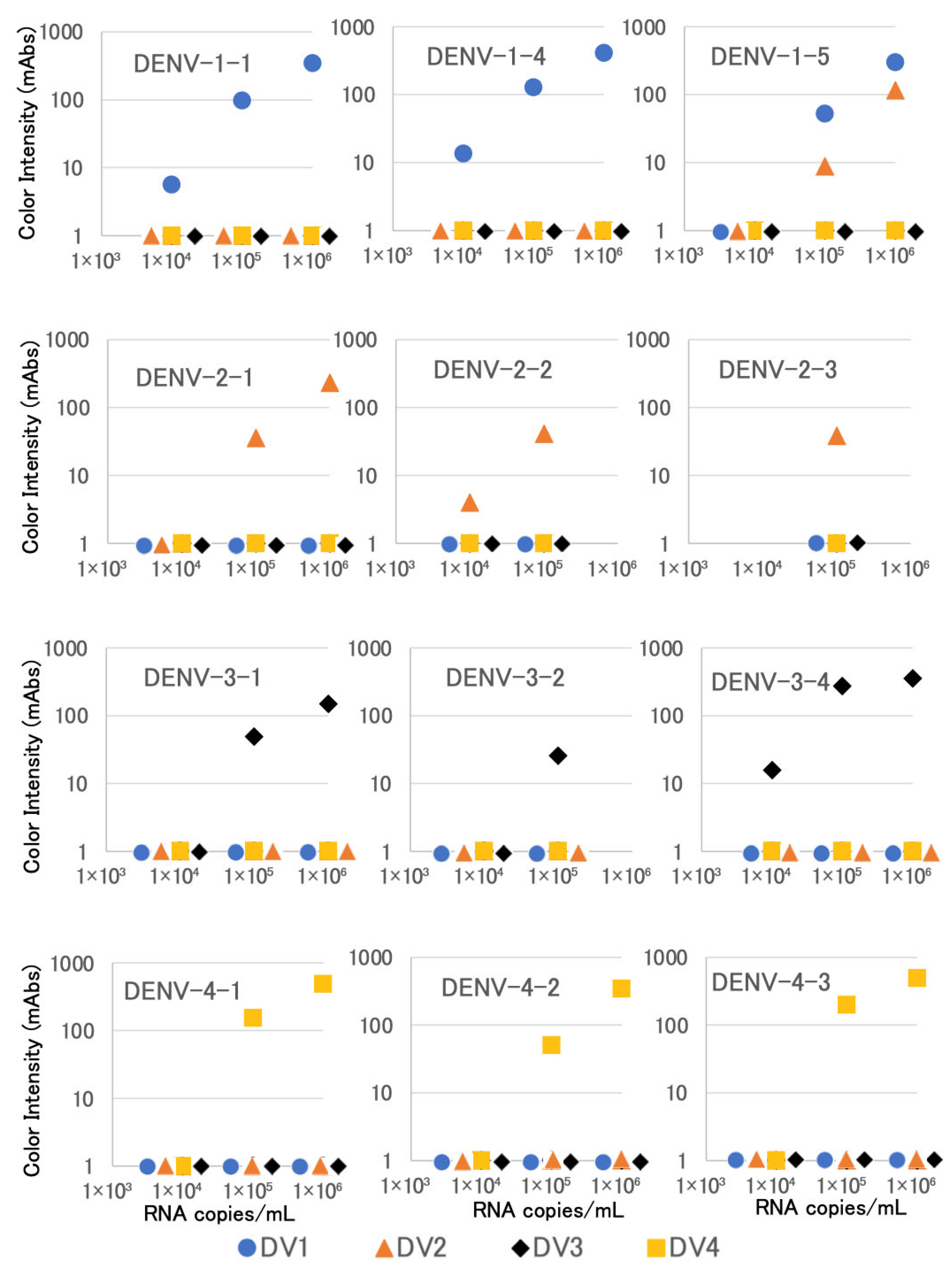

3.2. Detection of NS1 in Cultured Viruses

3.3. Detection of NS1 in Clinical Specimens in Thailand

3.4. Detection of NS1 in Clinical Specimens in Japan

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statements

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guzman, M.G.; Gubler, D.J.; Izquierdo, A.; Martinez, E.; Halstead, S.B. Dengue infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets, Dengue. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Postler, T.S.; Beer, M.; Blitvich, B.J.; Bukh, J.; de Lamballerie, X.; Drexler, J.F.; Imrie, A.; Kapoor, A.; Karganova, G.G.; Lemey, P.; et al. Renaming of the genus Flavivirus to Orthoflavivirus and extension of binomial species names within the family Flaviviridae. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H.; Michie, A.; Sasmono, R.T.; Imrie, A. Dengue: A Minireview. Viruses 2020, 12, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phadungsombat, J.; Lin, M.Y.-C.; Srimark, N.; Yamanaka, A.; Nakayama, E.E.; Moolasart, V.; Suttha, P.; Shioda, T.; Uttayamakul, S. Emergence of genotype Cosmopolitan of dengue virus type 2 and genotype III of dengue virus type 3 in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Phadungsombat, J.; Nakayama, E.E.; Saito, A.; Egawa, A.; Sato, T.; Rahim, R.; Hasan, A.; Lin, M.Y.-C.; Takasaki, T.; et al. Genotype replacement of dengue virus type 3 and clade replacement of dengue virus type 2 genotype Cosmopolitan in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2017. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 75, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltep, K.; Phadungsombat, J.; Nakayama, E.E.; Kosoltanapiwat, N.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; Wiriyarat, W.; Shioda, T.; Leaungwutiwong, P. Genetic Diversity of Dengue Virus in Clinical Specimens from Bangkok, Thailand, during 2018–2020: Co-Circulation of All Four Serotypes with Multiple Genotypes and/or Clades. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, R.; Hasan, A.; Phadungsombat, J.; Hasan, N.; Ara, N.; Biswas, S.M.; Nakayama, E.E.; Rahman, M.; Shioda, T. Genetic Analysis of Dengue Virus in Severe and Non-Severe Cases in Dhaka, Bangladesh, in 2018–2022. Viruses 2023, 15, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadungsombat, J.; Nakayama, E.E.; Shioda, T. Unraveling Dengue Virus Diversity in Asia: An Epidemiological Study through Genetic Sequences and Phylogenetic Analysis. Viruses 2024, 16, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, D.; Gómez, M.; Hernández, C.; Muñoz, M.; Campo-Palacio, S.; González-Robayo, M.; Montilla, M.; Pavas-Escobar, N.; Ramírez, J.D. Emergence of Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Cosmopolitan Genotype, Colombia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, M.; Pereira, L.A.; Santiago, G.A.; Fonseca, V.; Mendoza, M.P.G.; de Oliveira, C.; de Moraes, L.; Xavier, J.; Tosta, S.; Fristch, H.; et al. Emergence of Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Cosmopolitan Genotype, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1725–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-Alfaro, V.; Uribe-Calvo, M.J.; Corrales-Aguilar, E.; Murillo, T. Emergence of Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Cosmopolitan Genotype in Costa Rica. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2025, 112, 1300–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngwe Tun, M.M.; Muthugala, R.; Rajamanthri, L.; Nabeshima, T.; Buerano, C.C.; Morita, K. Emergence of Genotype I of Dengue Virus Serotype 3 during a Severe Dengue Epidemic in Sri Lanka in 2017. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, V.T.; Inward, R.P.D.; Gutierrez, B.; Nguyen, N.M.; Nguyen, P.T.; Rajendiran, I.; Cao, T.T.; Duong, K.T.H.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Yacoub, S. Reemergence of Cosmopolitan Genotype Dengue Virus Serotype 2, Southern Vietnam. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 2180–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Gresh, L.; Halloran, M.E.; Mercado, J.C.; Kuan, G.; Gordon, A.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Antibody-dependent enhancement of severe dengue disease in humans. Science 2017, 358, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltep, K.; Nakayama, E.E.; Sasaki, T.; Kurosu, T.; Takashima, Y.; Phadungsombat, J.; Kosoltanapiwat, N.; Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; Suwanpakdee, S.; Imad, H.A.; et al. Development of a Dengue Virus Serotype-Specific Non-Structural Protein 1 Capture Immunochromatography Method. Sensors 2021, 21, 7809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.P.; Chau, T.N.; Thuy, T.T.; Tuan, N.M.; Hoang, D.M.; Thien, N.T.; Lien le, B.; Quy, N.T.; Hieu, N.T.; Hien, T.T.; et al. Maternal antibody and viral factors in the pathogenesis of dengue virus in infants. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libraty, D.H.; Young, P.R.; Pickering, D.; Endy, T.P.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Green, S.; Vaughn, D.W.; Nisalak, A.; Ennis, F.A.; Rothman, A.L. High circulating levels of the dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 early in dengue illness correlate with the development of dengue hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 2002, 186, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessoff, K.; Delorey, M.; Sun, W.; Hunsperger, E. Comparison of two commercially available dengue virus (DENV) NS1 capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using a single clinical sample for diagnosis of acute DENV infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Jusoh, T.N.A.; Shueb, R.H. Performance Evaluation of Commercial Dengue Diagnostic Tests for Early Detection of Dengue in Clinical Samples. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 2017, 4687182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonnet, C.; Okandze, A.; Matheus, S.; Djossou, F.; Nacher, M.; Mahamat, A. Prospective evaluation of the SD BIOLINE Dengue Duo rapid test during a dengue virus epidemic. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 2441–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, P.S.; Almeida Junior, J.T.D.; Abreu, L.T.; Silva, C.G.; Souza, L.D.C.; Gomes, M.C.; Mendes, L.M.T.; Santos, E.M.D.; Romero, G.A.S. Validation and reliability of the rapid diagnostic test ‘SD Bioeasy Dengue Duo’ for dengue diagnosis in Brazil: A phase III study. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2018, 113, e170433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurosu, T.; Khamlert, C.; Phanthanawiboon, S.; Ikuta, K.; Anantapreecha, S. Highly efficient rescue of dengue virus using a co-culture system with mosquito/mammalian cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 394, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, P.Y.; Chang, S.F.; Kuo, Y.C.; Yueh, Y.Y.; Chien, L.J.; Sue, C.L.; Lin, T.H.; Huang, J.H. Development of group- and serotype-specific one-step SYBR green I-based real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for dengue virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 2408–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Nakayama, E.E.; Saito, A.; Egawa, A.; Sato, T.; Phadungsombat, J.; Rahim, R.; Abu Hasan, A.; Iwamoto, H.; Rahman, M.; et al. Evaluation of novel rapid detection kits for dengue virus NS1 antigen in Dhaka, Bangladesh, in 2017. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, P.K.; Parida, M.M.; Saxena, P.; Kumar, M.; Rai, A.; Pasha, S.T.; Jana, A.M. Emergence and continued circulation of dengue-2 (genotype IV) virus strains in northern India. J. Med. Virol. 2004, 74, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiton-Donato, K.; Alvarez, D.A.; Peláez-Carvajal, D.; Mercado, M.; Ajami, N.J.; Bosch, I.; Usme-Ciro, J.A. Molecular characterization of dengue virus reveals regional diversification of serotype 2 in Colombia. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, Y.; Chen-Germán, M.; Quiroz, E.; Carrera, J.P.; Cisneros, J.; Moreno, B.; Cerezo, L.; Martinez-Torres, A.O.; Moreno, L.; Barahona de Mosca, I.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Dengue in Panama: 25 Years of Circulation. Viruses 2019, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Van Smévoorde, M.; Piorkowski, G.; Emboulé, L.; Dos Santos, G.; Loraux, C.; Guyomard-Rabenirina, S.; Joannes, M.O.; Fagour, L.; Najioullah, F.; Cabié, A.; et al. Phylogenetic Investigations of Dengue 2019-2021 Outbreak in Guadeloupe and Martinique Caribbean Islands. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricou, V.; Minh, N.N.; Farrar, J.; Tran, H.T.; Simmons, C.P. Kinetics of Viremia and NS1 Antigenemia Are Shaped by Immune Status and Virus Serotype in Adults with Dengue. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erra, E.O.; Korhonen, E.M.; Voutilainen, L.; Huhtamo, E.; Vapalahti, O.; Kantele, A. Dengue in Travelers: Kinetics of Viremia and NS1 Antigenemia and Their Associations with Clinical Parameters. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainggolan, L.; Dewi, B.E.; Hakiki, A.; Pranata, A.J.; Sudiro, T.M.; Martina, B.; van Gorp, E. Association of viral kinetics, infection history, NS1 protein with plasma leakage among Indonesian dengue infected patients. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyen, H.T.; Ngoc, T.V.; Ha, d.T.; Hang, V.T.; Kieu, N.T.; Young, P.R.; Farrar, J.J.; Simmons, C.P.; Wolbers, M.; Wills, B.A. Kinetics of plasma viremia and soluble nonstructural protein 1 concentrations in dengue: Differential effects according to serotype and immune status. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biering, S.B.; Akey, D.L.; Wong, M.P.; Brown, W.C.; Lo, N.T.N.; Puerta-Guardo, H.; Tramontini Gomes de Sousa, F.; Wang, C.; Konwerski, J.R.; Espinosa, D.A.; et al. Structural basis for antibody inhibition of flavivirus NS1-triggered endothelial dysfunction. Science 2021, 371, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, R.; Hasan, A.; Phadungsombat, J.; Samune, Y.; Hasan, N.; Ara, N.; Biswas, S.M.; Nakayama, E.E.; Rahman, M.; Shioda, T. Genetic Analysis of Dengue Virus in Dhaka, Bangladesh, in 2023–2024. Manuscript in preparation.

| Device | Detection Antibody | Capture Antibodies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (gold-label) | (membrane-bound) | |||

| DENV-1 and -2 specific | A | E | F | |

| DENV-3 and -4 specific | B | D | G | H |

| DENV-1 | DENV-1 IC Results | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | OAA (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Results | + | − | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** |

| + | 31 | 18 | 63.27 | 100 | 87.32 |

| − | 0 | 93 | 49.77–76.76 | 100–100 | 81.85–92.80 |

| DENV-2 | DENV-2 IC Results | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | OAA (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Results | + | − | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** |

| + | 2 | 2 | 50 | 100 | 98.59 |

| − | 0 | 138 | 1–99 | 100–100 | 96.645–100 |

| DENV-3 | DENV-3 IC Results | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | OAA (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Results | + | − | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** |

| + | 1 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| − | 0 | 141 | − | 100–100 | 100–100 |

| DENV-4 | DENV-4 IC Results | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | OAA (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR Results | + | − | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** | 95% CI ** |

| + | 0 | 0 | − | 100 | − |

| − | 0 | 142 | − | 100–100 | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sretapunya, W.; Buranachat, T.; Prasomthong, M.; Tantikorn, R.; Sa-ngarsang, A.; Naemkhunthot, S.; Meephaendee, L.; Wongjaroen, P.; Tanaka, C.; Shimadzu, Y.; et al. An Improved Dengue Virus Serotype-Specific Non-Structural Protein 1 Capture Immunochromatography Method with Reduced Sample Volume. Biosensors 2025, 15, 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120802

Sretapunya W, Buranachat T, Prasomthong M, Tantikorn R, Sa-ngarsang A, Naemkhunthot S, Meephaendee L, Wongjaroen P, Tanaka C, Shimadzu Y, et al. An Improved Dengue Virus Serotype-Specific Non-Structural Protein 1 Capture Immunochromatography Method with Reduced Sample Volume. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):802. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120802

Chicago/Turabian StyleSretapunya, Warisara, Thitiya Buranachat, Montita Prasomthong, Rittichai Tantikorn, Areerat Sa-ngarsang, Sirirat Naemkhunthot, Laddawan Meephaendee, Pattara Wongjaroen, Chika Tanaka, Yoriko Shimadzu, and et al. 2025. "An Improved Dengue Virus Serotype-Specific Non-Structural Protein 1 Capture Immunochromatography Method with Reduced Sample Volume" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120802

APA StyleSretapunya, W., Buranachat, T., Prasomthong, M., Tantikorn, R., Sa-ngarsang, A., Naemkhunthot, S., Meephaendee, L., Wongjaroen, P., Tanaka, C., Shimadzu, Y., Ogata, K., Kaihatsu, K., Morita, R., Shirano, M., Phadungsombat, J., Sasaki, T., Kubota-Koketsu, R., Samune, Y., Nakayama, E. E., & Shioda, T. (2025). An Improved Dengue Virus Serotype-Specific Non-Structural Protein 1 Capture Immunochromatography Method with Reduced Sample Volume. Biosensors, 15(12), 802. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120802