4.1. Main Features Associated with Clinical Lameness in Dairy Cattle

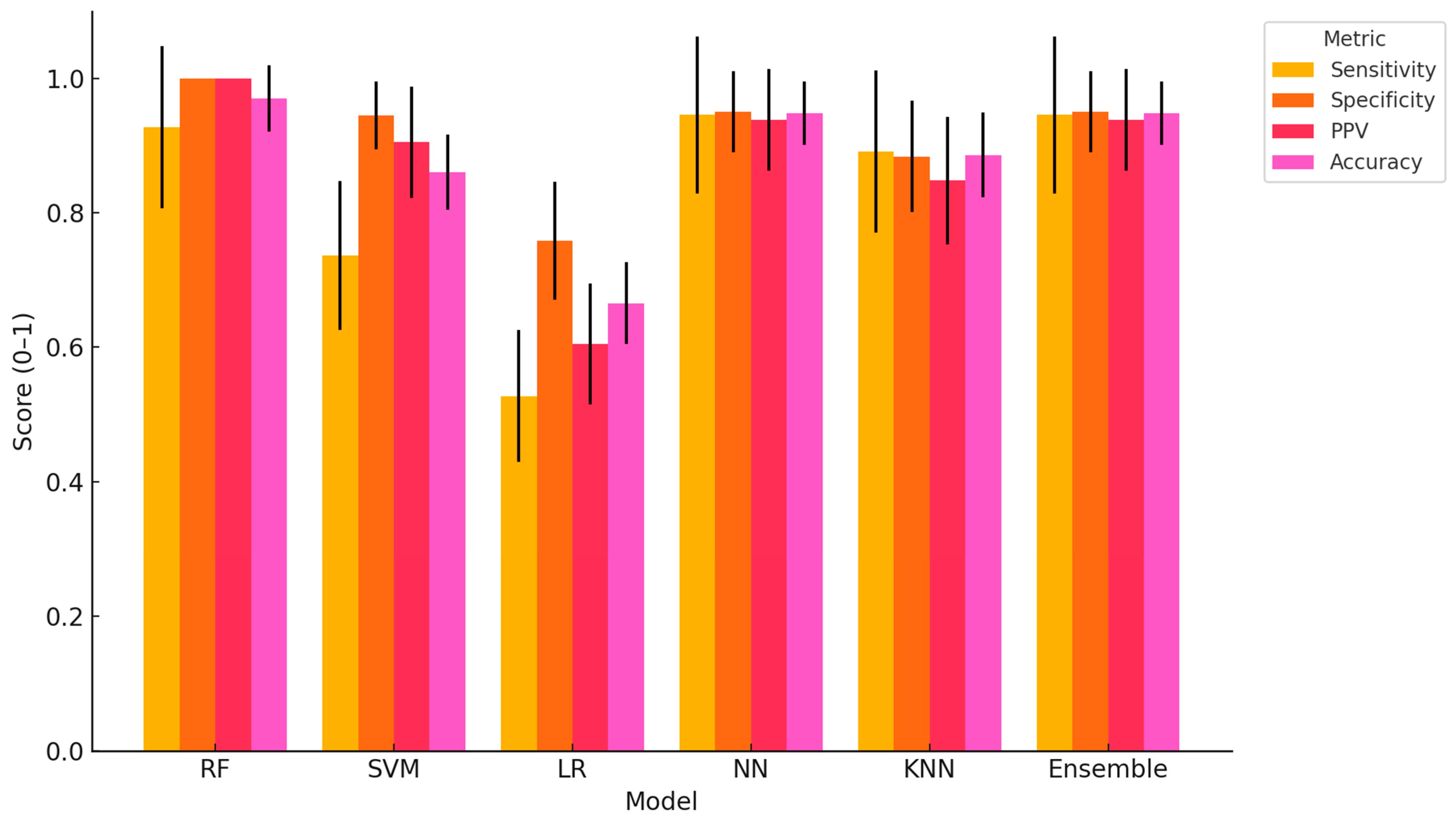

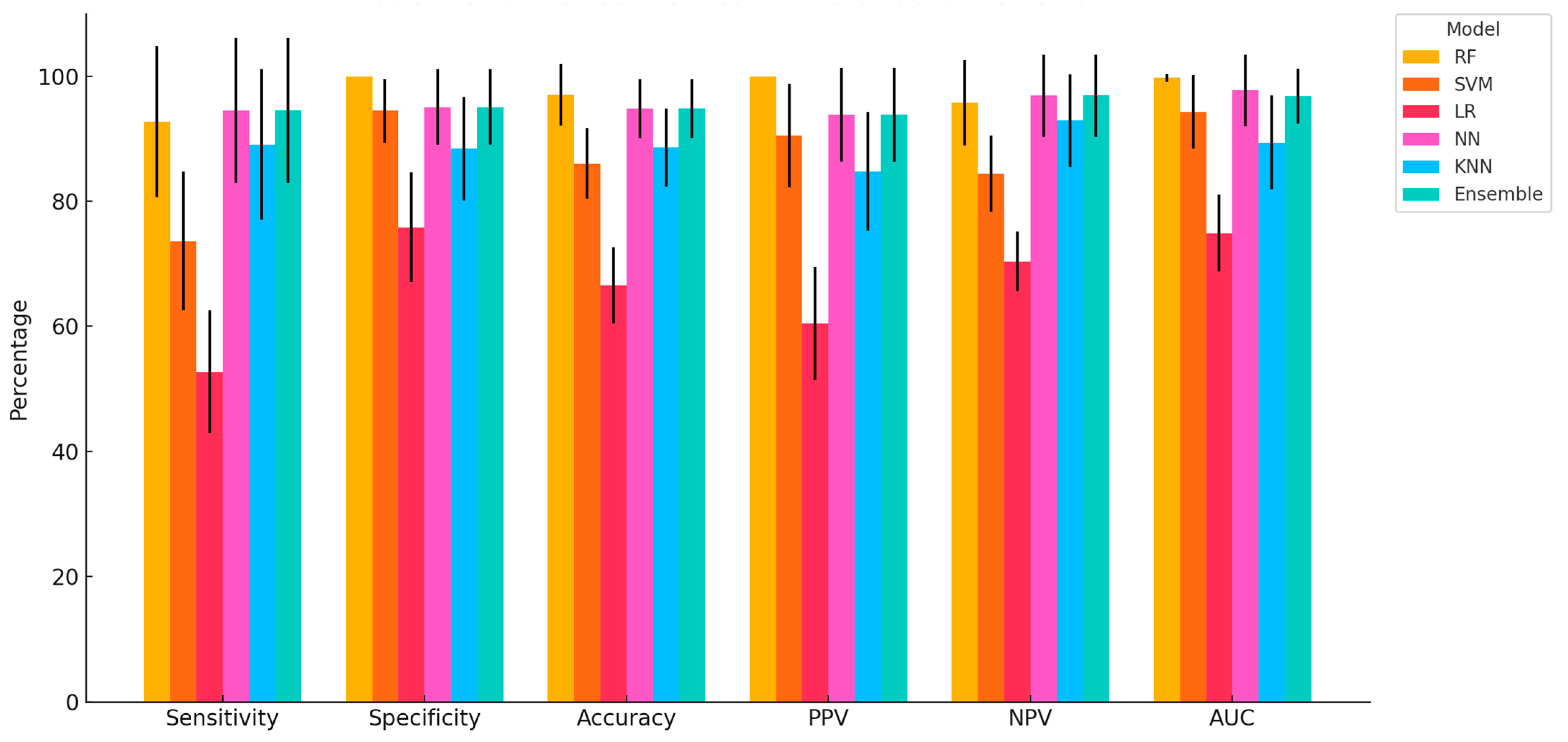

This study provides compelling evidence that ML algorithms, particularly RF, NN, and Ensemble models, can accurately classify dairy cows with clinically diagnosed lameness using a comprehensive, multimodal dataset encompassing physiological, behavioural, blood-based, and milk composition variables. The high classification accuracy achieved by RF (97.04%), coupled with perfect specificity and PPV, demonstrates the strong predictive capability of tree-based models in handling heterogeneous, nonlinear data. NN and the Ensemble model also performed consistently well across all performance metrics, further validating their capacity to capture complex biological interactions associated with lameness. Similar findings have been reported in other contexts; for example, in a study evaluating classification models for lameness treatment events, RF was compared with LR and Gaussian Naïve Bayes. Although the RF model achieved a more modest performance (AUC = 0.71) for lameness detection based on sensor-derived variables such as pedometer activity and feed intake, it was still recommended as a benchmark model owing to its interpretability and consistent predictive ability. Interestingly, other authors also observed that oversampling techniques did not enhance AUC, reinforcing RF’s robustness under different modelling conditions [

27]. Indeed, previous research in dairy cattle health monitoring confirms the suitability of RF in such contexts: for example, Dineva et al. [

28] applied RF to classify cow health status using heterogeneous IoT and sensor data and achieved an accuracy of 0.959, with recall 0.954 and precision 0.97 [

28].

The superiority of RF and NN observed in this study aligns with previous research indicating that models capable of handling nonlinear, high-dimensional data outperform simpler linear methods in animal health applications [

9,

29,

30]. In contrast, LR, a linear model, showed limited predictive value, with the lowest sensitivity (52.73%) and AUC (74.89%) among all tested models. This aligns with earlier findings, where logistic regression models for lameness detection generally achieved only moderate accuracy, with AUC values ranging from 0.70 to 0.77 [

31]. One explanation for this limited performance is that LR assumes linear relationships between predictors and outcomes, whereas lameness in dairy cows arises from multi-factorial and nonlinear physiological processes. Pain-induced alterations in gait, weight redistribution, and locomotor asymmetry interact with changes in feed intake, rumination time, and milk yield, all of which are influenced by metabolic and inflammatory states [

32]. Such complex interactions are not easily captured by linear models.

Among the models evaluated, SVM and KNN demonstrated intermediate performance. SVM showed high specificity (94.49%) but lower sensitivity (73.64%), suggesting a bias toward correctly identifying healthy animals while under-detecting truly lame cows. This could lead to an increased risk of false negatives in practical settings. KNN displayed balanced but slightly lower overall performance, which may be attributed to its sensitivity to feature scaling and data noise. In line with these observations, previous work has shown that an Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model trained on step-size feature vectors achieved a lameness detection accuracy of 98.57%, outperforming SVM, KNN, and Decision Tree Classifier (DTC) by margins of 2.93%, 3.88%, and 9.25%, respectively [

33], further emphasizing the advantage of advanced nonlinear models in capturing gait-related abnormalities. Complementing our findings, Neupane et al. [

34] evaluated ML models using accelerometer-derived behavioural data (day-to-day lying time, step counts, and their trends) for detecting lameness and the need for corrective or therapeutic claw treatments. They found that the ROCKET time-series classifier, particularly when combining conventional and slope features, significantly outperformed RF, Naïve Bayes, and LR—achieving accuracies > 90%, ROC–AUCs > 0.74, and F1-scores > 0.61 for identifying cows needing intervention [

34]. Post et al. [

27] developed classification models for both mastitis and lameness treatment events using daily individual sensor data—such as milking parameters, pedometer activity, feed and water intake, and body weight. They compared various ML methods (LR, SVM, KNN, Gaussian Naïve Bayes, Extra Trees (ET), and RF, and found the ET classifier achieved the highest mean AUC of 0.79 for mastitis and 0.71 for lameness, closely followed by Gaussian Naïve Bayes, LR, and RF—highlighting good interpretability alongside competitive performance [

27]. A recent study by Lemmens et al. [

35] demonstrated that integrating sensor data, automated milking system (AMS) parameters, and farm-level information substantially improved the detection of mild lameness (locomotion score ≥ 2). Their RF model achieved an accuracy of approximately 0.75, with a sensitivity of 0.72 and a specificity of 0.78. Importantly, eating time, low activity, medium activity, and activity trends differed significantly between lame and non-lame cows, whereas rumination time remained largely unaffected [

35].

The Ensemble model, integrating predictions from RF, NN, and SVM, provided robust performance across all metrics and may serve as a practical compromise when aiming to balance specificity, sensitivity, and interpretability. Its consistent classification accuracy and relatively low variation across Monte Carlo cross-validations point to its potential as a stable and generalizable tool for on-farm decision support. Similarly, Yuhao Shen et al. [

36] described an ensemble learning approach for detecting cow lameness, where an improved YOLOv8-Pose model was used to identify key points on the hooves, knees, hips, and head, and motion features were fused through a stacking ensemble method, achieving an overall accuracy of 97.2% [

36].

The clinical relevance of the models’ performance is underscored by the biological interpretation of key input features. For example, lame cows exhibited significantly lower water intake and higher reticulorumen and body temperatures—traits likely reflective of discomfort, inflammatory responses, or altered metabolic function. Biomarkers such as NEFA, GGT, AST, and LDH were also significantly altered in lame cows, supporting the hypothesis that lameness is accompanied by systemic physiological and metabolic changes. Interestingly, Meléndez et al. [

37] demonstrated that acute health disorders in dairy cows can induce measurable shifts in serum metabolic profiles, including GGT activity, thereby supporting the notion that alterations in this enzyme are part of a broader systemic response to disease rather than isolated anomalies [

37]. Reduced AST levels observed in our study may also point toward compromised metabolic processes; however, it is important to acknowledge that the relationship between lameness and AST activity remains inconsistent in the literature, with some report describing unchanged values [

38,

39]. These findings concur with Praxitelous et al. [

40], who documented higher GGT concentrations in lame cows during the puerperium period (25.83 vs. 23.56,

p = 0.02) [

40], as well as with un-targeted metabolomics work by He et al. [

41], which identified lipid-metabolism metabolites as discriminative markers in lame dairy cattle [

41]. Furthermore, scoping reviews such as Sadiq et al. [

42] consistently list NEFA and liver enzymes among the most frequently studied biomarkers linked to lameness in dairy cows [

42]. In addition, Dineva et al. [

28] demonstrated that a RF classifier using heterogeneous sensor and physiological data achieved high predictive accuracy (0.959), recall (0.954) and precision (0.97)—evidence for the utility of combining diverse biological signals in health monitoring [

28]. These discrepancies suggest that biochemical responses to lameness are likely influenced by the severity, chronicity, and underlying causes of locomotor impairment, as well as by concurrent metabolic and inflammatory conditions. Notably, elevated NEFA levels in lame cows suggest increased lipomobilization, which may reflect an underlying energy imbalance or stress-induced metabolic shift. These findings are consistent with prior studies that have identified NEFA and liver enzymes as important indicators of systemic inflammation and metabolic stress in dairy cattle.

From a milk production perspective, lame cows showed reduced milk protein and lactose content, further highlighting the systemic impact of lameness on metabolic efficiency and mammary gland function. Although overall milk yield was not significantly different, the compositional shifts in milk underline the potential of milk traits as non-invasive biomarkers for health monitoring. Kass et al. [

43], in a study of Estonian Holstein cows, demonstrated that lame individuals produced significantly less milk overall, with concomitant decreases in milk protein and fat yield compared to their non-lame counterparts [

43]. Furthermore, our previous studies showed that milk lactose dynamics are also altered around the onset of lameness: healthy cows had significantly lower lactose levels com-pared to lame cows both on the day of diagnosis (−2.15%) and seven days thereafter (−1.73%), suggesting that lameness is associated with transient changes in lactose synthesis and secretion [

44]. Indeed, in the study by Jukna et al. [

45], severe lameness was associated with a decrease in milk lactose concentration by 0.16 percentage points (

p < 0.001) as lameness severity intensified, supporting the notion that lameness alters milk composition [

45]. Moreover, Bonfatti et al. [

46] explored the use of milk mid-infrared spectra to predict lameness scores, suggesting that deviations in milk spectral traits may reflect underlying metabolic disturbances, which in turn influence milk composition [

46].

The effectiveness of our predictive models for lameness is underscored by the biological and physiological significance of their key input features. We observed that lame cows exhibit reduced water intake and elevated body temperature. The elevated body temperature is a clear physiological marker of inflammation, a process where the cow redirects energy and resources away from productive behaviours like milk synthesis and toward pain management and tissue repair. Further supporting this link, a separate study by Antanaitis et al. [

47] demonstrated that changes in reticulorumen temperature patterns coincided with the onset of clinical lameness, highlighting the strong connection between these physiological indicators and the manifestation of the disease [

47]. Therefore, our models’ reliance on these specific behavioural and physiological features is biologically justified, reinforcing their clinical relevance for early lameness detection.

Interestingly, rumination time and cow activity did not differ significantly between groups, which may suggest behavioural compensation in lame animals or highlight the difficulty of relying on these measures in isolation for lameness detection. Weigele et al. [

48] observed that moderate lameness had no significant impact on rumination time, number of ruminating chews, or boluses, suggesting that basic rumination behaviour remains relatively stable despite locomotor impairment [

48]. Likewise, Thorup et al. [

49] reported that lameness did not affect daily rumination time, number of rumination events, or overall rumination behaviour, even though feeding behaviour was clearly altered. From a physiological standpoint, this stability may be explained by the cow’s strong homeostatic drive to maintain rumen function and fiber digestion, which are essential for sustaining microbial fermentation and volatile fatty acid production, even when mobility is compromised [

50]. Consequently, lame cows may preserve rumination behaviour while reducing other energy-demanding activities, such as locomotion or the frequency of visits to the feed bunk [

51]. These findings underscore that rumination and activity data, when used in isolation, may fail to capture the multifactorial nature of lameness, highlighting the need to integrate them with gait-related metrics, weight distribution patterns, or biochemical indicators to achieve more reliable detection. This further justifies the use of multimodal data integration in model development. The inclusion of both objective sensor data and clinically relevant biomarkers strengthens the interpretability and real-world applicability of the resulting models.

4.2. Reflections on Strengths, Limitations, and Scientific Outlook

One of the main strengths of this study lies in its integrative approach to lameness classification, combining physiological, behavioural, blood biochemical, and milk composition data into a comprehensive ML framework. This multimodal design reflects the multifactorial nature of lameness and allows for more biologically meaningful classification models than approaches that rely on single data streams. By evaluating six different algorithms and incorporating robust cross-validation, the study offers a clear and comparative picture of model performance and stability. The consistent superiority of Random Forest, Neural Networks, and the Ensemble model demonstrates the power of non-linear and ensemble methods to capture complex patterns in real-world, farm-derived data. Although preliminary feature importance analysis was conducted, the relatively limited sample size and intercorrelated structure of the dataset may have affected the stability of variable ranking. Future studies with larger, longitudinal datasets are needed to derive more robust interpretability measures.

Another important strength is the biological interpretability of the input features. Several of the indicators that differed significantly between lame and healthy cows—such as water intake, NEFA levels, liver enzymes (GGT, AST, LDH), milk protein, and lactose content—are not only statistically significant but also physiologically relevant, reinforcing the clinical validity of the model outputs. These findings support the growing role of sensor and biomarker-based monitoring systems in veterinary diagnostics.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. The models do not predict the onset of lameness but rather classify cows as lame or healthy based on their current biological status. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge that the models developed in this study serve as diagnostic aids rather than predictive tools. Because the data were collected at the time of clinical diagnosis, the models classify cows according to their current physiological and biochemical status and do not predict the future onset of lameness. This distinction is important for setting realistic expectations about their practical application. Moreover, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits conclusions about the temporal progression of lameness or the dynamics of the involved indicators over time.

Another constraint is the absence of external validation. While the models performed well under internal cross-validation, their generalizability to other farms, management systems, or cow populations remains to be tested. Additionally, behavioural variables such as rumination time and activity did not show significant differences between groups, possibly due to adaptation or masking behaviours in lame cows. This suggests that sensor-based behavioural indicators alone may not be sufficiently sensitive or specific for detecting lameness without additional physiological or biochemical context. It should also be noted that a moderate class imbalance existed in the dataset (healthy cows = 162; lame cows = 110). Although stratified sampling and balanced evaluation metrics such as MCC and nMCC were used to mitigate its effects, linear models like Logistic Regression may still be more sensitive to such imbalance, which could have contributed to their comparatively lower performance.

Looking ahead, future research should focus on longitudinal data collection and repeated measurements across the disease trajectory to evaluate whether these multimodal ML models can be adapted for pre-clinical prediction, relapse monitoring, or progression assessment. External validation using independent datasets from commercial farms is also essential to assess model scalability and real-world applicability. Lastly, integrating genetic, environmental, and management variables could further refine model accuracy and resilience across diverse production settings.

In summary, this study contributes a robust, multimodal framework for clinical classification of lameness in dairy cows and highlights the utility of combining biosensor data with milk and blood biomarkers. While not predictive, the models offer a promising diagnostic support tool that can enhance the objectivity, consistency, and efficiency of veterinary decision-making within precision dairy systems.