Water Sampling Module for Collecting and Concentrating Legionella pneumophila from Low-to-Medium Contaminated Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms and Materials

2.2. Preparation of Bacteria in Suspension

2.3. Water Sampling Module

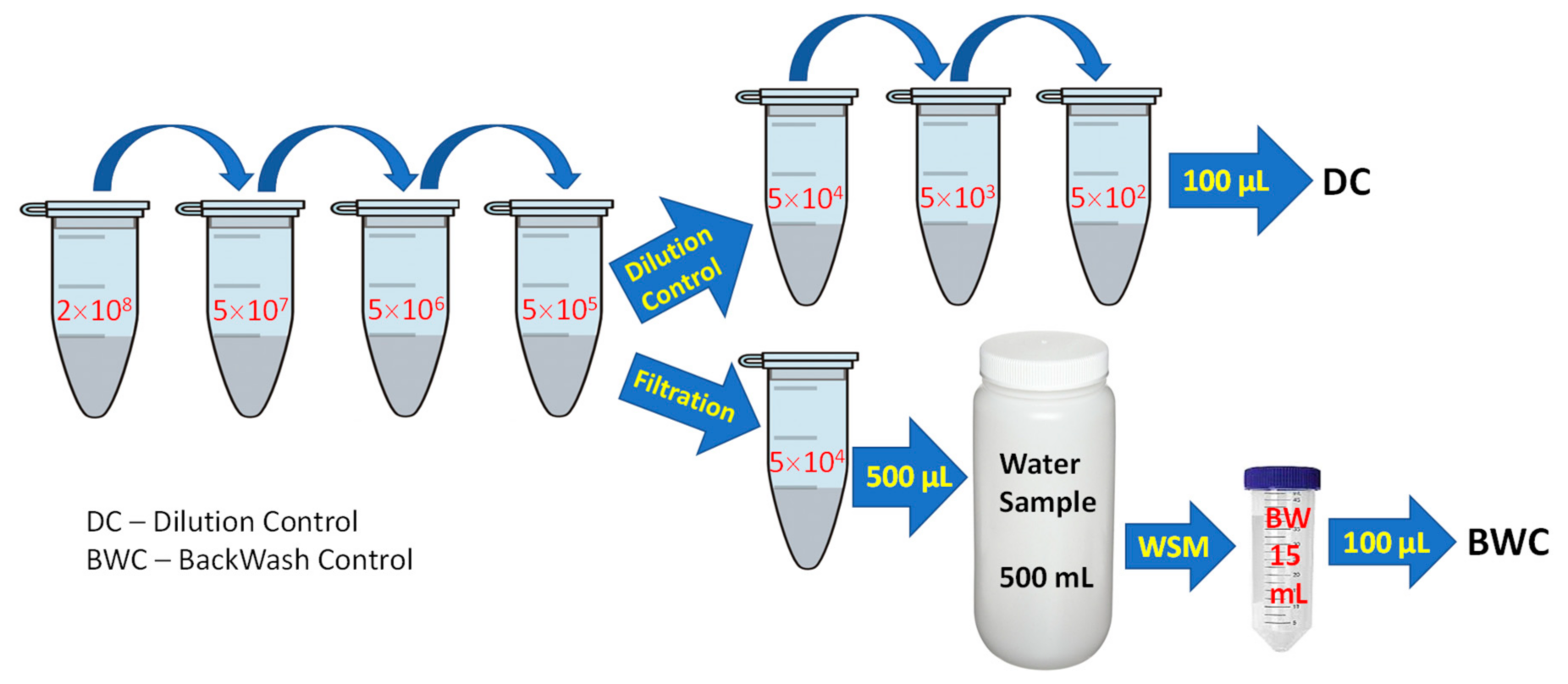

2.4. Standard Operating Procedure

2.5. WSM Decontamination Procedure

2.6. Acid Treatment

2.7. Filtration of Saline Samples Spiked with E. coli

2.8. Dilution and Filtration of Saline Samples Spiked with L. pneumophila at 50 CFU/mL

2.9. Filtration of Cooling Tower Water (CTW) Samples Spiked with L. pneumophila at 50 CFU/mL

2.10. Growth of the Backwashed Filtrate and Bacteria Quantitation

3. Results

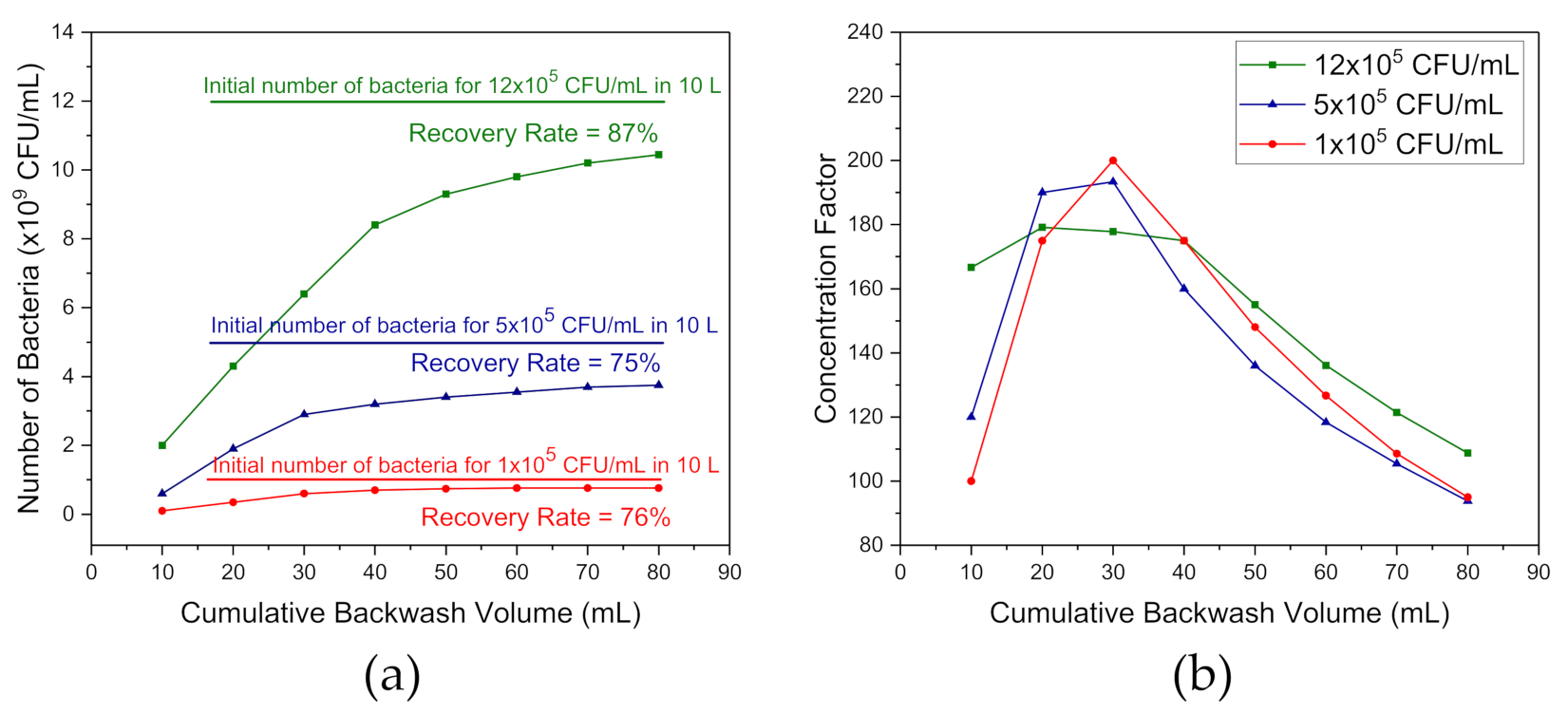

3.1. Recovery Rates and Concentration Factors of Samples Spiked with E. coli

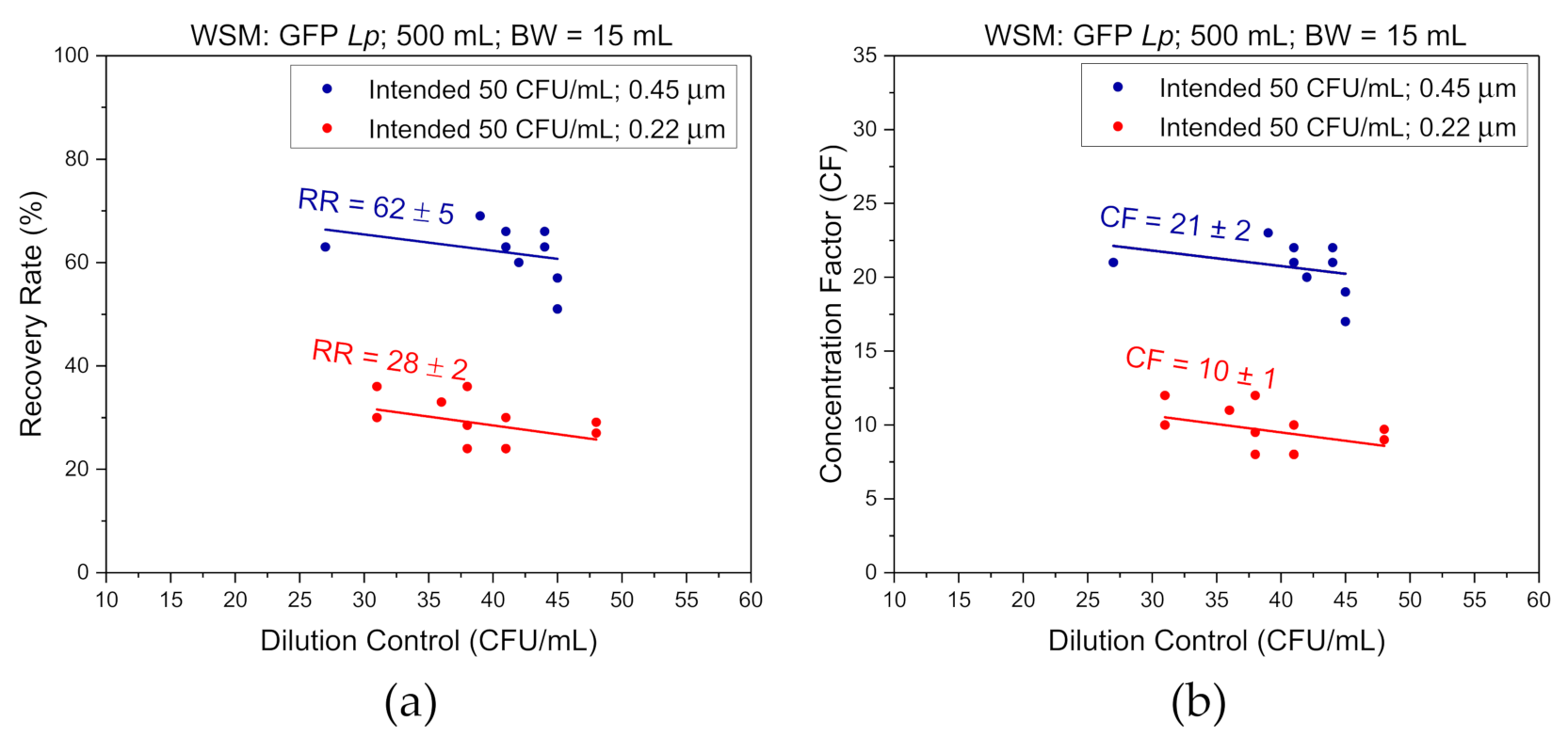

3.2. Recovery Rates and Concentration Factors of L. pneumophila in Saline Solution

3.3. Recovery Rates and Concentration Factors of L. pneumophila in Saline Solution Following Acid Treatment

3.4. Recovery Rates and Concentration Factors of L. pneumophila in Acid Treated Industrial Water

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaradou, D.F.; Hallier-Soulier, S.; Moreau, S.; Poty, F.; Hillion, Y.; Reyrolle, M.; Andre, J.; Festoc, G.; Delabre, K.; Vandenesch, F.; et al. Integrated real-time PCR for detection and monitoring of Legionella pneumophila in water systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.S.I.; Jiménez, M.; Sabater, M.; Martínez, M.A.; Bedrina, B.; Lázaro, M.; Ceña, S.; Puig, A.; Davide, D.; Fisac, C. Automatic Early Warning System to Detect and Quantify Legionella Species in Cooling Towers. Bacteriol. Mycol. 2018, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, C.R.; Dyda, A.; Bui, C.M.; Chughtai, A.A. Rolling epidemic of Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks in small geographic areas. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzhenry, R.; Weiss, D.; Cimini, D.; Balter, S.; Boyd, C.; Alleyne, L.; Stewart, R.; McIntosh, N.; Econome, A.; Lin, Y.; et al. Legionnaires’ Disease Outbreaks and Cooling Towers, New York City, New York, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercante, J.W.; Winchell, J.M. Current and emerging Legionella diagnostics for laboratory and outbreak investigations. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 95–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.-Y.; Lin, Y.E.; Lin, W.-R.; Shih, H.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Ben, R.-J.; Huang, W.-K.; Chen, Y.-S.; Liu, Y.-C.; Chang, F.-Y.; et al. The high prevalence of Legionella pneumophila contamination in hospital potable water systems in Taiwan: Implications for hospital infection control in Asia. Int. Infect. Dis. 2008, 12, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpers, P.; Tiede, A.; Kirschner, P.; Girke, J.; Ganser, A.; Peest, D. Legionnaires’ disease in immunocompromised patients: A case report of Legionella longbeachae pneumonia and review of the literature. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.E.; Stout, J.E.; Yu, V.L. Prevention of hospital-acquired legionellosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 24, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, T.; Osicki, R.A.; Springthorpe, V.S.; Sattar, S.A.; Filion, L.; Abrial, D.; Riffard, S. Detection and identification of Legionella species from groundwaters. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2004, 67, 1845–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegra, S.; Leclerc, L.; Massard, P.A.; Girardot, F.; Riffard, S.; Pourchez, J. Characterization of aerosols containing Legionella generated upon nebulization. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Türetgen, I.; Sungur, E.I.; Cotuk, A. Enumeration of Legionella pneumophila in cooling tower water systems. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2005, 100, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, C.; Lin, J.; Wu, W.; Ashbolt, N.J.; Liu, W.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Effect of Disinfectant Exposure on Legionella pneumophila Associated with Simulated Drinking Water Biofilms: Release, Inactivation, and Infectivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buse, H.Y.; Morris, B.J.; Struewing, I.T.; Szabo, J.G. Chlorine and Monochloramine Disinfection of Legionella pneumophila Colonizing Copper and Polyvinyl Chloride Drinking Water Biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02956-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Khweek, A.; Amer, A.O. Factors mediating environmental biofilm formation by Legionella pneumophila. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gast, R.J.; Moran, D.M.; Dennett, M.R.; Wurtsbaugh, W.A.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. Amoebae and Legionella pneumophila in saline environments. J. Water Health 2011, 9, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Tomonaga, M.; Tsukasaki, K.; Kohno, S.; Seki, M.; Sugimoto, H.; Shimazu, T.; Tasaki, O.; Matsushima, A. Evaluation of pathogen detection from clinical samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction using a sepsis pathogen DNA detection kit. Crit. Care 2010, 14, R159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Rothman, R.E. PCR-based diagnostics for infectious diseases: Uses, limitations, and future applications in acute-care settings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, L.; Luo, J.L.; Hibbs, D.E.; Perry, J.D.; Anderson, R.J.; Orenga, S.; Groundwater, P.W. Methods for the detection and identification of pathogenic bacteria: Past, present, and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 4818–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagier, J.-C.; Edouard, S.; Pagnier, I.; Mediannikov, O.; Drancourt, M.; Raoult, D. Current and past strategies for bacterial culture in clinical microbiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 208–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.H.; Kim, J. Cultivation of unculturable soil bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, N.; Kumar, M.; Kanaujia, P.K.; Virdi, J.S. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: An emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasch, P.; Jacob, D.; Grunow, R.; Schwecke, T.; Doellinger, J. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) for the identification of highly pathogenic bacteria. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 85, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantakokko-Jalava, K.; Jalava, J. Development of conventional and real-time PCR assays for detection of Legionella DNA in respiratory specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 2904–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giglio, O.; Diella, G.; Trerotoli, P.; Consonni, M.; Palermo, R.; Tesauro, M.; Laganà, P.; Serio, G.; Montagna, M.T. Legionella Detection in Water Networks as per ISO 11731: 2017: Can Different Filter Pore Sizes and Direct Placement on Culture Media Influence Laboratory Results? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, K.D.; Gargano, J.W.; Roberts, V.A.; Hill, V.R.; Garrison, L.E.; Kutty, P.K.; Hilborn, E.D.; Wade, T.J.; Fullerton, K.E.; Yoder, J.S. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks associated with drinking water—United States, 2011–2012. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2015, 64, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; UNICEF; ICCIDD. Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring Their Elimination; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Walser, S.M.; Gerstner, D.G.; Brenner, B.; Höller, C.; Liebl, B.; Herr, C.E. Assessing the environmental health relevance of cooling towers–a systematic review of legionellosis outbreaks. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, J.; Chartier, Y.; Lee, J.V.; Pond, K.; Surman-Lee, S. Legionella and the Prevention of Legionellosis; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, K.; Uchiyama, I.; Okumura, J. Assessing the risk of Legionnaires’ disease: The inhalation exposure model and the estimated risk in residential bathrooms. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013, 65, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.A.; Hamilton, M.T.; Johnson, W.; Jjemba, P.; Bukhari, Z.; LeChevallier, M.; Haas, C.N.; Gurian, P. Risk-based critical concentrations of Legionella pneumophila for indoor residential water uses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4528–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Hill, V.R.; Hahn, D.; Johnson, T.B.; Pan, Y.; Jothikumar, N.; Moe, C.L. Hollow-fiber ultrafiltration for simultaneous recovery of viruses, bacteria and parasites from reclaimed water. J. Microbiol. Methods 2012, 88, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sboui, D.; Souiri, M.; Reynaud, S.; Palle, S.; Ismail, M.B.; Epalle, T.; Mzoughi, R.; Girardot, F.; Allegra, S.; Riffard, S. Characterisation of electrochemical immunosensor for detection of viable not-culturable forms of Legionella pneumophila in water samples. Chem. Pap. 2015, 69, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedrina, B.; Macian, S.; Solis, I.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Baldrich, E.; Rodriguez, G. Fast immunosensing technique to detect Legionella pneumophila in different natural and anthropogenic environments: Comparative and collaborative trials. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziziyan, M.R.; Hassen, W.M.; Morris, D.; Frost, E.H.; Dubowski, J.J. Photonic biosensor based on photocorrosion of GaAs/AlGaAs quantum heterostructures for detection of Legionella pneumophila. Biointerphases 2016, 11, 019301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazemi, E.; Hassen, W.M.; Frost, E.H.; Dubowski, J.J. Monitoring growth and antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli with photoluminescence of GaAs/AlGaAs quantum well microstructures. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 93, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.A.; Hassen, W.M.; Tayabali, A.F.; Dubowski, J.J. Antimicrobial warnericin RK peptide functionalized GaAs/AlGaAs biosensor for highly sensitive and selective detection of Legionella pneumophila. Biochem. Eng. J. 2020, 154, 107435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grib, H.; Moumanis, K.; Hassen, W.M.; Dubowski, J.J. Selective Area Nd: YAG Laser Functionalization of Digital Photocorrosion GaAs/AlGaAs Biosensor. J. Laser Micro/Nanoeng. 2020, 15, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, R.C.; Schonewill, P.P.; Shimskey, R.W.; Peterson, R.A. A Brief Review of Filtration Studies for Waste Treatment at the Hanford Site; Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A Guide to Drinking Water Treatment Technologies for Household Use; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015.

- Solutions, D.W. Filmtec™ Reverse Osmosis Membranes. Tech. Manual Form. 2010, 399, 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Dunets, S.; Cayanan, D. COPPER-Silver IONIZATION. Greenhouse and Nusery Water Treatment Information. View. 2012. Available online: www.ces.uoguelph.ca/water/PATHOGEN/CopperIonization.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, T.; Xu, C.; Hong, L. Optimization of an enhanced ceramic micro-filter for concentrating E. coli in water. In Proceedings of the Imaging, Manipulation, and Analysis of Biomolecules, Cells, and Tissues XV, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16 February 2017; p. 100681B. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.-Q.; Guo, T.; Hong, L. An automated bacterial concentration and recovery system for pre-enrichment required in rapid Escherichia coli detection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, V.R.; Polaczyk, A.L.; Hahn, D.; Narayanan, J.; Cromeans, T.L.; Roberts, J.M.; Amburgey, J.E. Development of a rapid method for simultaneous recovery of diverse microbes in drinking water by ultrafiltration with sodium polyphosphate and surfactants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 6878–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaczyk, A.L.; Narayanan, J.; Cromeans, T.L.; Hahn, D.; Roberts, J.M.; Amburgey, J.E.; Hill, V.R. Ultrafiltration-based techniques for rapid and simultaneous concentration of multiple microbe classes from 100-L tap water samples. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 73, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Morales, H.A.; Vidal, G.; Olszewski, J.; Rock, C.M.; Dasgupta, D.; Oshima, K.H.; Smith, G.B. Optimization of a reusable hollow-fiber ultrafilter for simultaneous concentration of enteric bacteria, protozoa, and viruses from water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4098–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, N.K.; Fredrickson, J.K.; Fishbain, S.; Wagner, M.; Stahl, D.A. Population structure of microbial communities associated with two deep, anaerobic, alkaline aquifers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winona, L.; Ommani, A.; Olszewski, J.; Nuzzo, J.; Oshima, K. Efficient and predictable recovery of viruses from water by small scale ultrafiltration systems. Can. J. Microbiol. 2001, 47, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magaña, S.; Schlemmer, S.M.; Leskinen, S.D.; Kearns, E.A.; Lim, D.V. Automated dead-end ultrafiltration for concentration and recovery of total coliform bacteria and laboratory-spiked Escherichia coli O157: H7 from 50-liter produce washes to enhance detection by an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. J. Food Prot. 2013, 76, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Noga, R.; Shanov, V.; Ryu, H.; Chandra, H.; Yadav, B.; Yadav, J.; Chae, S. Electrically heatable carbon nanotube point-of-use filters for effective separation and in-situ inactivation of Legionella pneumophila. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 366, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Twest, R.; Kropinski, A.M. Bacteriophage enrichment from water and soil. In Bacteriophages; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Waritani, T.; Chang, J.; McKinney, B.; Terato, K. An ELISA protocol to improve the accuracy and reliability of serological antibody assays. MethodsX 2017, 4, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Iwasawa, T.; Saruwatari, Y.; Agata, K. Improved acid pretreatment for the detection of Legionella species from environmental water samples using the plate culture method. Biocontrol Sci. 2004, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, P.H.; Roy, C.R. Legionnaires’ disease and pontiac fever. Mandell Douglas Bennett’s Princ. Pract. Infect. Dis. 2015, 10, 2633–2644. [Google Scholar]

- Bopp, C.; Sumner, J.; Morris, G.; Wells, J. Isolation of Legionella spp. from environmental water samples by low-pH treatment and use of a selective medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1981, 13, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francy, D.S.; Stelzer, E.A.; Brady, A.M.; Huitger, C.; Bushon, R.N.; Ip, H.S.; Ware, M.W.; Villegas, E.N.; Gallardo, V.; Lindquist, H.A. Comparison of filters for concentrating microbial indicators and pathogens in lake water samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holowecky, P.; James, R.; Lorch, D.; Straka, S.; Lindquist, H. Evaluation of ultrafiltration cartridges for a water sampling apparatus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 106, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iritani, E.; Katagiri, N.; Inagaki, G. Compression and expansion properties of filter cake accompanied with step change in applied pressure in membrane filtration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 198, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, S.E.; Celis-Salgado, M.P.; Valleau, R.E.; DeSellas, A.M.; Paterson, A.M.; Yan, N.D.; Smol, J.P.; Rusak, J.A. Road salt impacts freshwater zooplankton at concentrations below current water quality guidelines. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 9398–9407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, T.V.; Parsons, J.R.; Rijnaarts, H.H.; de Voogt, P.; Langenhoff, A.A. A review on the removal of conditioning chemicals from cooling tower water in constructed wetlands. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 48, 1094–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, F.A.; Siddiqui, R.; Khan, N.A. Acanthamoeba castellanii of the T4 genotype is a potential environmental host for Enterobacter aerogenes and Aeromonas hydrophila. Parasites Vectors 2013, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, S.; Kearns, E.; Jones, W.; Miller, R.; Bevitas, C.; Kingsley, M.; Brigmon, R.; Lim, D. Automated dead-end ultrafiltration of large volume water samples to enable detection of low-level targets and reduce sample variability. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassen, W.M.; Sanyal, H.; Hammood, M.; Moumanis, K.; Frost, E.H.; Dubowski, J.J. Chemotaxis for enhanced immobilization of Escherichia coli and Legionella pneumophila on biofunctionalized surfaces of GaAs. Biointerphases 2016, 11, 021004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenarro, J.J.; Párraga-Niño, N.; Sabrià, M.; Del Campo, F.J.; Muñoz-Pascual, F.-X.; Mas, J.; Uria, N. Rapid Detection of Legionella pneumophila in Drinking Water, Based on Filter Immunoassay and Chronoamperometric Measurement. Biosensors 2020, 10, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average DC (CFU/mL) | Average BWC (CFU/mL) | RR (%) (BWC × 15 mL/DC × 500 mL) | CF (BWC/DC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 875 | 88 | 29 |

| 44 | 1100 | 75 | 25 |

| 39 | 884 | 68 | 23 |

| 41 | 870 | 64 | 21 |

| 45 | 870 | 58 | 19 |

| 45 | 750 | 50 | 17 |

| 42 | 830 | 59 | 20 |

| 44 | 960 | 65 | 22 |

| 44 | 910 | 62 | 21 |

| 41 | 873 | 64 | 21 |

| Average DC (CFU/mL) | Average BWC (CFU/mL) | RR (%) (BWC × 15 mL/DC × 500 mL) | CF (BWC/DC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 56 | 280 | 15 | 5 |

| 37 | 185 | 15 | 5 |

| 37 | 149 | 12 | 4 |

| 44 | 262 | 18 | 6 |

| 45 | 220 | 15 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moumanis, K.; Sirbu, L.; Hassen, W.M.; Frost, E.; Carvalho, L.R.d.; Hiernaux, P.; Dubowski, J.J. Water Sampling Module for Collecting and Concentrating Legionella pneumophila from Low-to-Medium Contaminated Environment. Biosensors 2021, 11, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios11020034

Moumanis K, Sirbu L, Hassen WM, Frost E, Carvalho LRd, Hiernaux P, Dubowski JJ. Water Sampling Module for Collecting and Concentrating Legionella pneumophila from Low-to-Medium Contaminated Environment. Biosensors. 2021; 11(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios11020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoumanis, Khalid, Lilian Sirbu, Walid Mohamed Hassen, Eric Frost, Lydston Rodrigues de Carvalho, Pierre Hiernaux, and Jan Jerzy Dubowski. 2021. "Water Sampling Module for Collecting and Concentrating Legionella pneumophila from Low-to-Medium Contaminated Environment" Biosensors 11, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios11020034

APA StyleMoumanis, K., Sirbu, L., Hassen, W. M., Frost, E., Carvalho, L. R. d., Hiernaux, P., & Dubowski, J. J. (2021). Water Sampling Module for Collecting and Concentrating Legionella pneumophila from Low-to-Medium Contaminated Environment. Biosensors, 11(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios11020034