Reusable Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrates Made of Silicon Nanowire Array Coated with Silver Nanoparticles Fabricated by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching and Photonic Reduction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

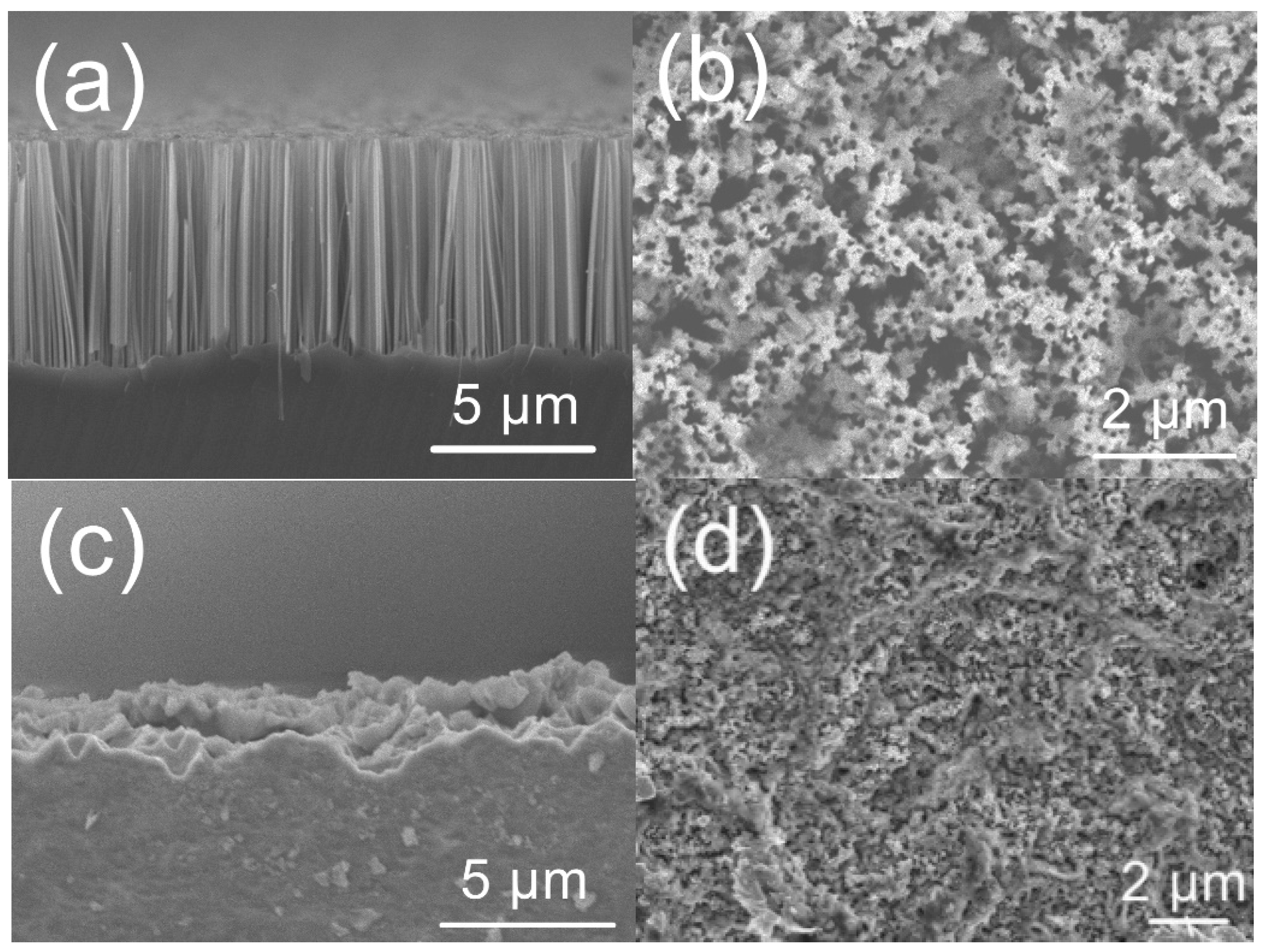

2.1. Silicon Nanowire Array Fabrication by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching

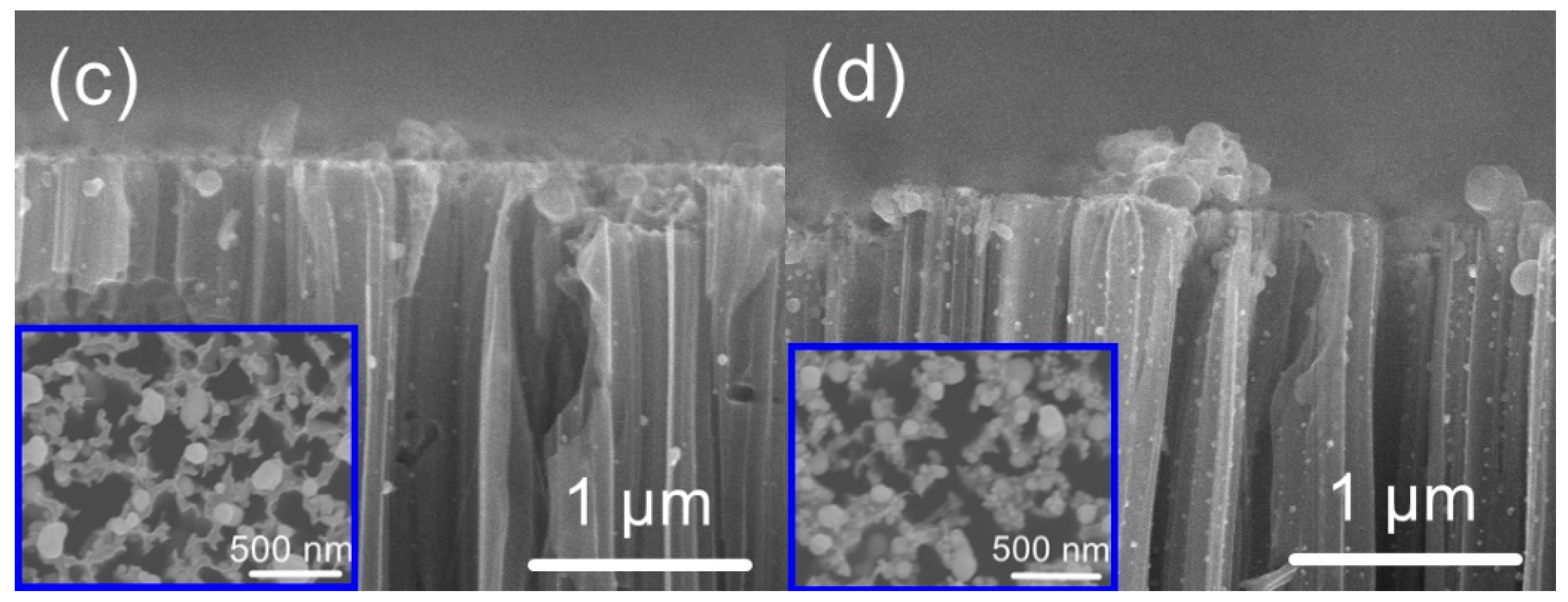

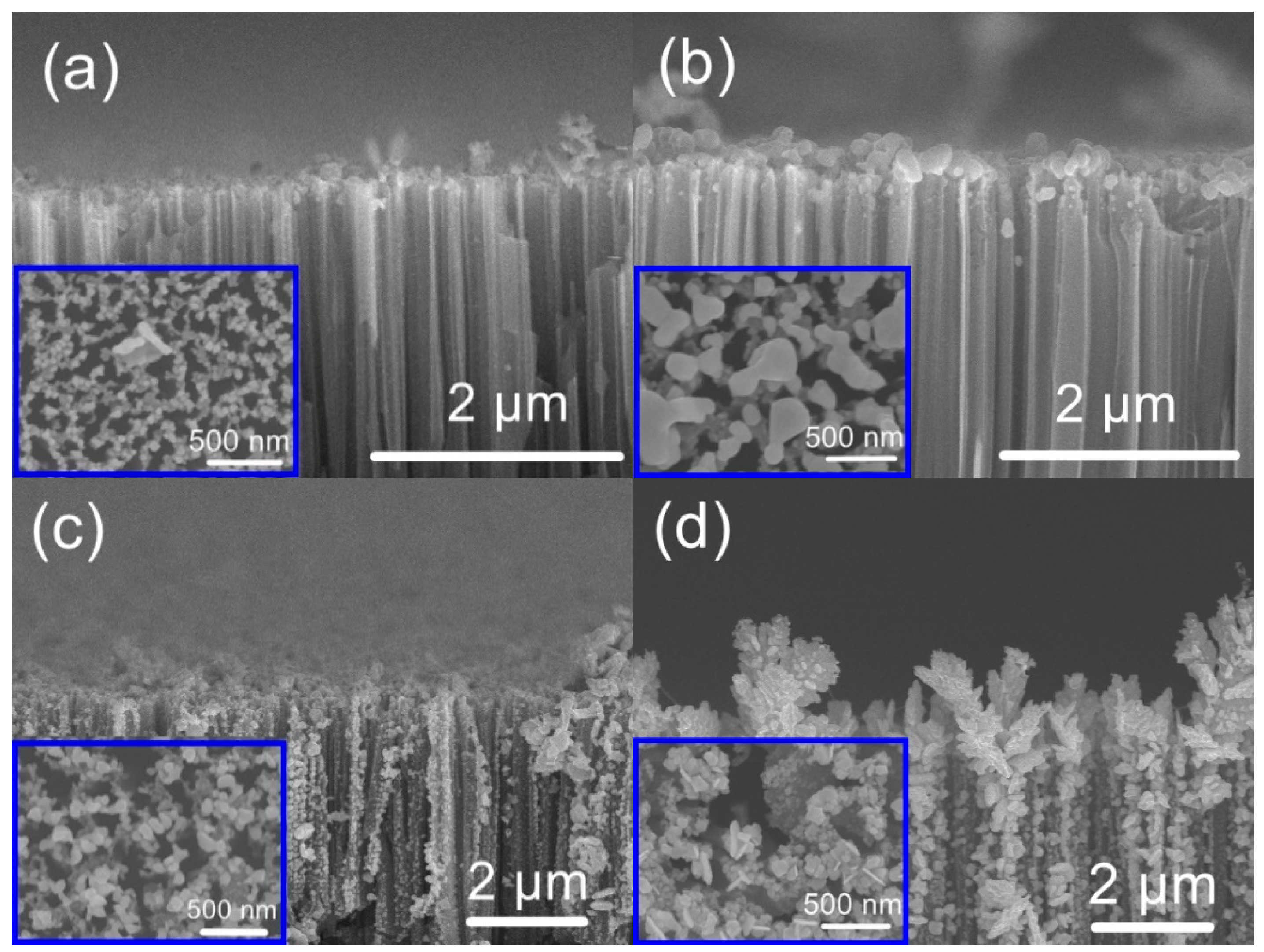

2.2. Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Photonic Reduction

2.3. SERS Analyses

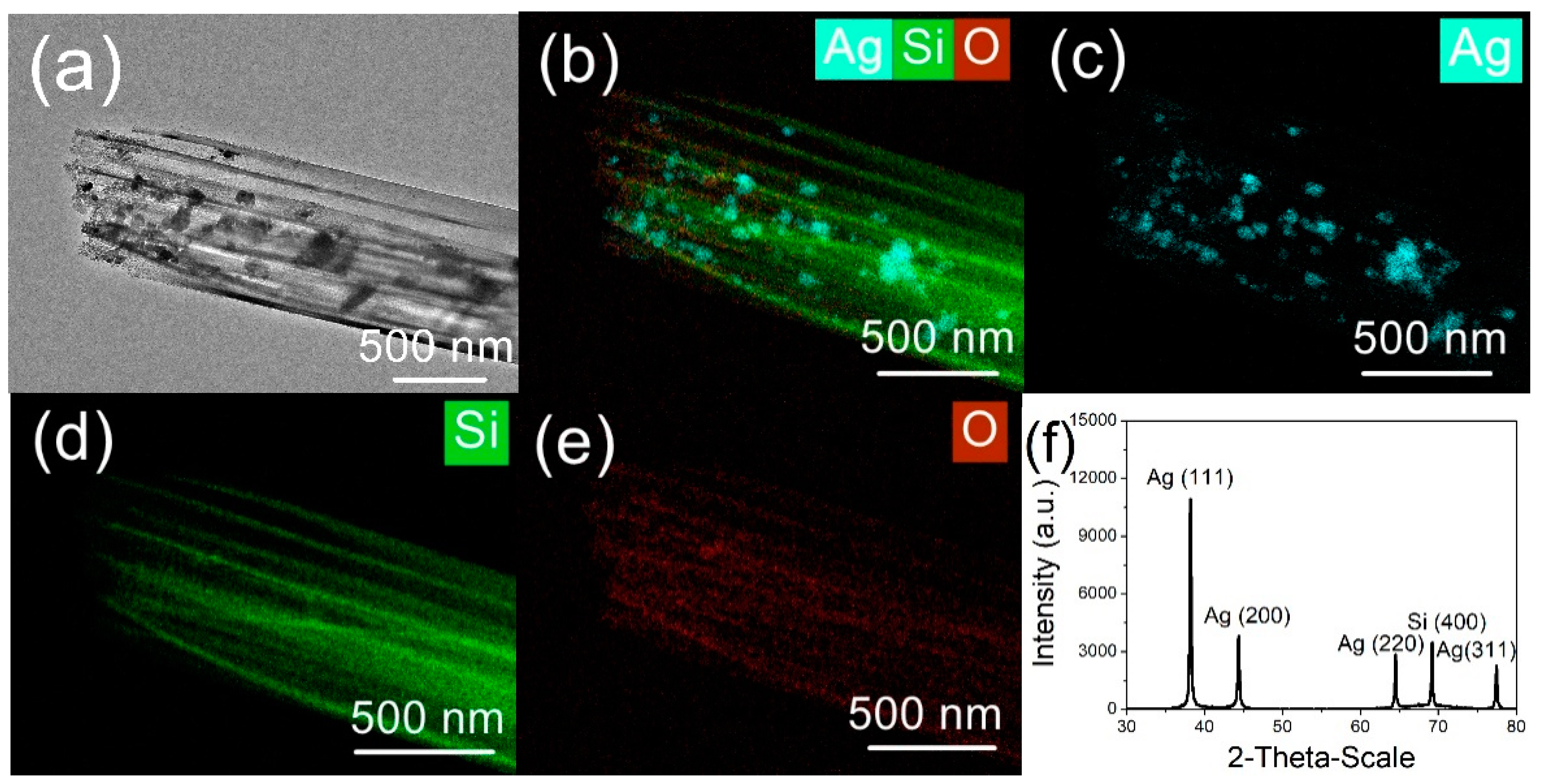

2.4. Characterization

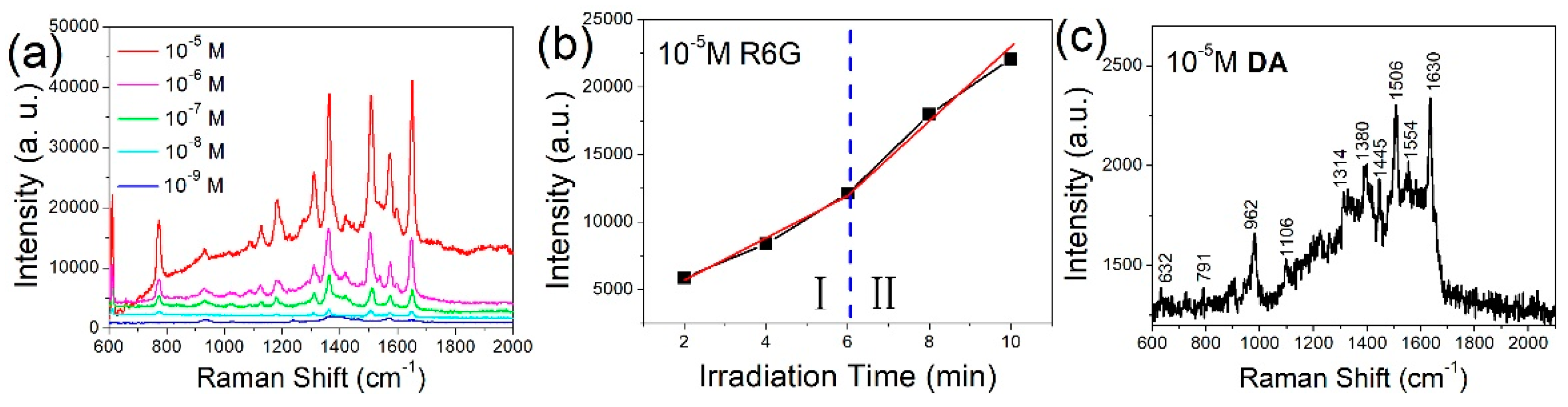

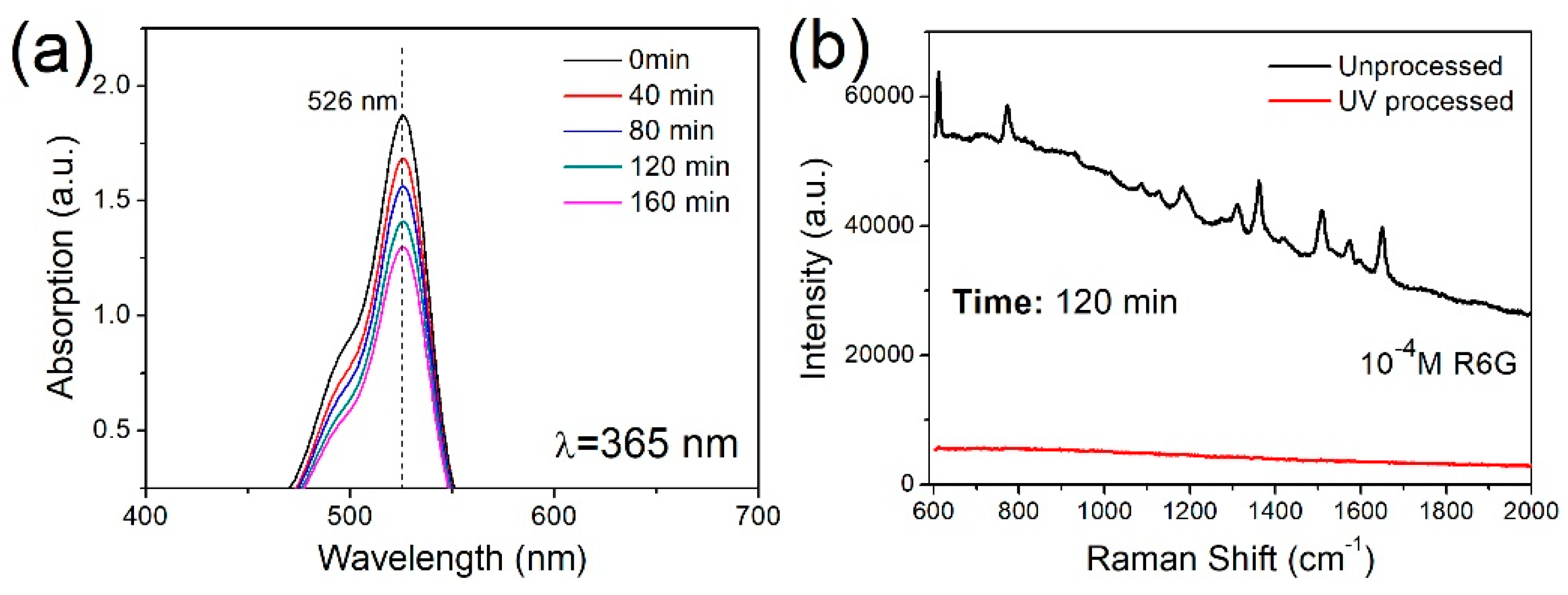

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zengin, A.; Tamer, U.; Caykara, T. A SERS-Based Sandwich Assay for Ultrasensitive and Selective Detection of Alzheimer’s Tau Protein. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3001–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, S.; Lin, Y.H.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhou, W.P.; Chen, T.; Ma, Y.; Hou, T.X.; Bridges, D.; Oakes, K.; Hu, A.M. Two-Step Photonic Reduction of Controlled Periodic Silver Nanostructures for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Plasmonics 2015, 10, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozyk, M.S.; de Aberasturi, D.J.; Gregory, J.V.; Brust, M.; Lahann, J.; Liz-Marzan, L.M. Spatial Analysis of Metal-PLGA Hybrid Microstructures Using 3D SERS Imaging. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Serien, D.; Hu, A.M.; Sugioka, K. 3D Microfluidic Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Chips Fabricated by All-Femtosecond-Laser-Processing for Real-Time Sensing of Toxic Substances. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1706262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.A.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.J.; He, L.F.; Wong, T.L.; Chui, Y.S.; Zhang, W.J.; Lee, S.T. Ordered Ag/Si Nanowires Array: Wide-Range Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Reproducible Biomolecule Detection. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 5039–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.D.; Wu, Z.L.; Li, S.J.; Zhao, W.Q.; Ma, C.J.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.M.; Zhong, Z.Y.; Zheng, Y.B.; Yang, X.J. Large-Area Au-Nanoparticle-Functionalized Si Nanorod Arrays for Spatially Uniform Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.D.; Yin, Y.G.; Tan, Z.Q.; Liu, J.F. Coffee-ring effect-based simultaneous SERS substrate fabrication and analyte enrichment for trace analysis. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9588–9593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Y.; Jin, J.; Tian, W.J.; Li, R.; Yu, Z.; Song, W.; Cong, Q.; Zhao, B.; Ozaki, Y. Three-dimensional superhydrophobic surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy substrate for sensitive detection of pollutants in real environments. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 4330–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Meng, G.W.; Li, Z.B.; Huang, Z.L.; Li, X.D. Ag-NP@Ge-nanotaper/Si-micropillar ordered arrays as ultrasensitive and uniform surface enhanced Raman scattering substrates. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 18218–18224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.Z.; Yin, P.G.; You, T.T.; Wang, H.; Guo, L. Three Dimensional Design of Large-Scale TiO2 Nanorods Scaffold Decorated by Silver Nanoparticles as SERS Sensor for Ultrasensitive Malachite Green Detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 3432–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.J.; Jeong, K.H. Glass Nanopillar Arrays with Nanogap-Rich Silver Nanoislands for Highly Intense Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2234–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.G.; Mun, C.; Xiao, X.F.; Braun, A.; Kim, S.; Giannini, V.; Maier, S.A.; Kim, D.H. Surface Energy-Controlled SERS Substrates for Molecular Concentration at Plasmonic Nanogaps. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1703376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.K.; Park, S.G.; Ko, J.; Xiao, X.F.; Giannini, V.; Maier, S.A.; Kim, D.H.; Choo, J. Sensitive and Reproducible Immunoassay of Multiple Mycotoxins Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Mapping on 3D Plasmonic Nanopillar Arrays. Small 2018, 14, 1801623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.T.; Barron, A.R. Nanopore-type black silicon anti-reflection layers fabricated by a one-step silver-assisted chemical etching. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 9862–9870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.L.; Peng, K.Q.; Fan, X.; Jie, J.S.; Zhang, R.Q.; Lee, S.T.; Wong, N.B. Preparation of large-area uniform silicon nanowires arrays through metal-assisted chemical etching. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 4444–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Ma, W.H.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X.H.; Xiao, Y.Y.; Ma, M.Y.; Zhu, W.J.; Wei, F. Fabrication of porous silicon nanowires by MACE method in HF/H2O2/AgNO3 system at room temperature. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Du, Y.; Wang, C.; Bai, S.; Zhang, T.; Chen, T.; Hu, A. Reusable and long-life 3D Ag nanoparticles coated Si nanowires array as sensitive SERS substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 494, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wong, C. Unveiling the shape-diversified silicon nanowires made by HF/HNO 3 isotropic etching with the assistance of silver. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Kumar, D.; Schmitt, S.W.; Sood, K.N.; Christiansen, S.H.; Singh, P.K. Large area fabrication of vertical silicon nanowire arrays by silver-assisted single-step chemical etching and their formation kinetics. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 175601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Mei, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Liang, H.; Kuznetsov, A.; Du, X. Maskless inverte pyramid texturizaion of silicon. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhlin, Y.L.; Vishnyakova, E.A.; Romanchenko, A.S.; Saikova, S.V.; Likhatski, M.N.; Larichev, Y.V.; Tuzikov, F.V.; Zaikovskii, V.I.; Zharkov, S.M. Oxidation of Ag nanoparticles in aqueous media: Effect of particle size and capping. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 297, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminuzzan, M.; Watanabe, A.; Miyashita, T. Direct writing of conductive silver micropatterns on flexible polyimide film by laser-induced pyrolysis of silver nanoparticle-dispersed film. J. Nnaopart. Res. 2010, 12, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Bai, S.; Hu, A. Photo-reduction of metallic ions doped in patterned polymer films for the fabrication of plasmonic photonic crystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 6046–6052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, J. Fabrication of Large-Area Silicon Nanowire p-n Jjunction Diode Arrays. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajvardi, M.; Eshghi, H.; Izadifard, M.; Ghazi, M.E.; Goodarzi, A. Effects of silver and gold catalytic activities on the structural and optical properties of silicon nanowires. Phys. E 2016, 75, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, S.D.; Fadhali, M.M.; Areshi, R.A.; Tan, F.D. Optical and Electrical Characteristics of Silicon Nanowires Prepared by Electroless Etching. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Yang, A.S.; Xiong, J.H. Green, microwave-assisted synthesis of silver nanoparticles using bamboo hemicelluloses and glucose in an aqueous medium. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 91, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, S.; Park, D.R.; Shin, H.S. Silicon nanowires arrays for visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of rose bengal dye. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 10460–10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ru, E.C.; Blackie, E.; Meyer, M.; Etchegoin, P.G. Surface enhanced Raman scattering enhancement factors: A comprehensive study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 13794–13803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Meng, G.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, C. Arrays of cone-shaped ZnO nanorods decorated with Ag nanoparticles as 3D surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates for rapid detection of trace polychlorinated biphenyls. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Li, X.; Blinn, K.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Liu, M. Resonant surface enhancement of Raman scattering of Ag nanoparticles on silicon substrates fabricated by dc sputtering. J. Vaccum Sci. Technol. A 2012, 30, 050606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.F.; You, H.J.; Fang, J.X. Three-dimensional noble-metal nanostructure: A new kind of substrate for sensitive, uniform, and reproducible surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Chin. Phys. B 2014, 23, 087801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Qu, S.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Huo, Y.; Li, G. Simultaneous SEF and SERRS from silver fractal-like nanostructure. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2014, 191, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.F.; Xu, C.X.; Nan, H.Y.; Zhu, Q.X.; Qin, F.F.; Manohari, A.G.; Wei, M.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, Z.L.; Ni, Z.H. SERS-active ZnO/Ag hybrid WGM microcavity for ultrasensitive dopamine detection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 073701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.T.; He, X.X.; Yang, T.Q.; Zhao, L.T.; Chen, Q.C.; Zhang, S.J.; Chen, J.Q.; Xu, J.H. Sensitive determination of dopamine levels via surface-enhanced Raman scattering of Ag nanoparticle dimers. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 2337–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J.; Shen, M.Z.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, F.; Sun, D.P.; Wang, T.H. A simple technique for direct growth of Au into a nanoporous alumina layer on conductive glass as a reusable SERS substrate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 406, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Wu, T.; Han, X.Z.; Gu, H.X.; Zhang, X. A needle-like reusable surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrate, and its application to the determination of acetamiprid by combining SERS and thin-layer chromatography. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Ghosh, J.; Das, R.; Mawlong, L.P.L.; Paul, K.K.; Giri, P.K. Multifunctional Ag nanoparticle decorated Si nanowires for sensing, photocatalysis and light emission applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 532, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.T.; Wang, J.L.; Mei, L.R.; Wang, X.Y. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B by Cu2O Coated Silicon Nanowire Arrays in Presence of H2O2. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2014, 30, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Devnani, H.; Jha, S.; Ingole, P.P. Fermi level equilibration of Ag and Au plasmonic metal nanoparticles supported on graphene oxide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 26719–26733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, S.; Du, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Sugioka, K. Reusable Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrates Made of Silicon Nanowire Array Coated with Silver Nanoparticles Fabricated by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching and Photonic Reduction. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9111531

Bai S, Du Y, Wang C, Wu J, Sugioka K. Reusable Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrates Made of Silicon Nanowire Array Coated with Silver Nanoparticles Fabricated by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching and Photonic Reduction. Nanomaterials. 2019; 9(11):1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9111531

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Shi, Yongjun Du, Chunyan Wang, Jian Wu, and Koji Sugioka. 2019. "Reusable Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrates Made of Silicon Nanowire Array Coated with Silver Nanoparticles Fabricated by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching and Photonic Reduction" Nanomaterials 9, no. 11: 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9111531

APA StyleBai, S., Du, Y., Wang, C., Wu, J., & Sugioka, K. (2019). Reusable Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Substrates Made of Silicon Nanowire Array Coated with Silver Nanoparticles Fabricated by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching and Photonic Reduction. Nanomaterials, 9(11), 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9111531