Sustainable Lavender Extract-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Use in Fabricating Antibacterial Polymer Nanocomposites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Extract

2.2. Biological Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

2.3. Nanocomposite Production

2.4. Methods

2.5. Antibacterial Testing of AgNPs and Nanocomposites

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Silver Nanoparticles Analysis

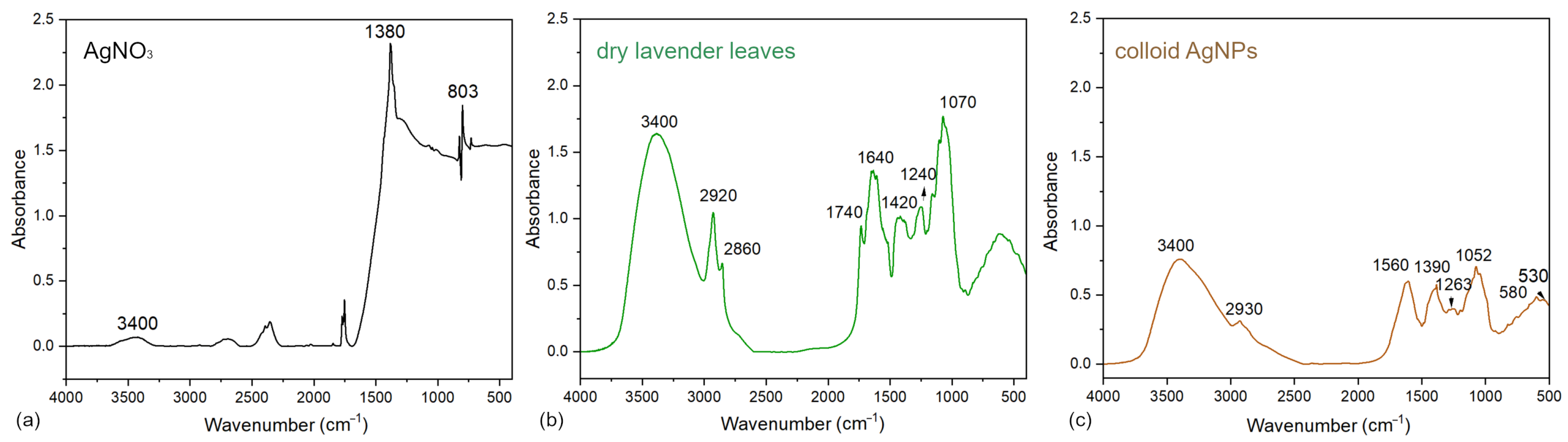

3.1.1. FTIR Spectroscopy of Precursor, Extract, and Colloid

3.1.2. Mechanism of AgNPs Formation and Stabilization

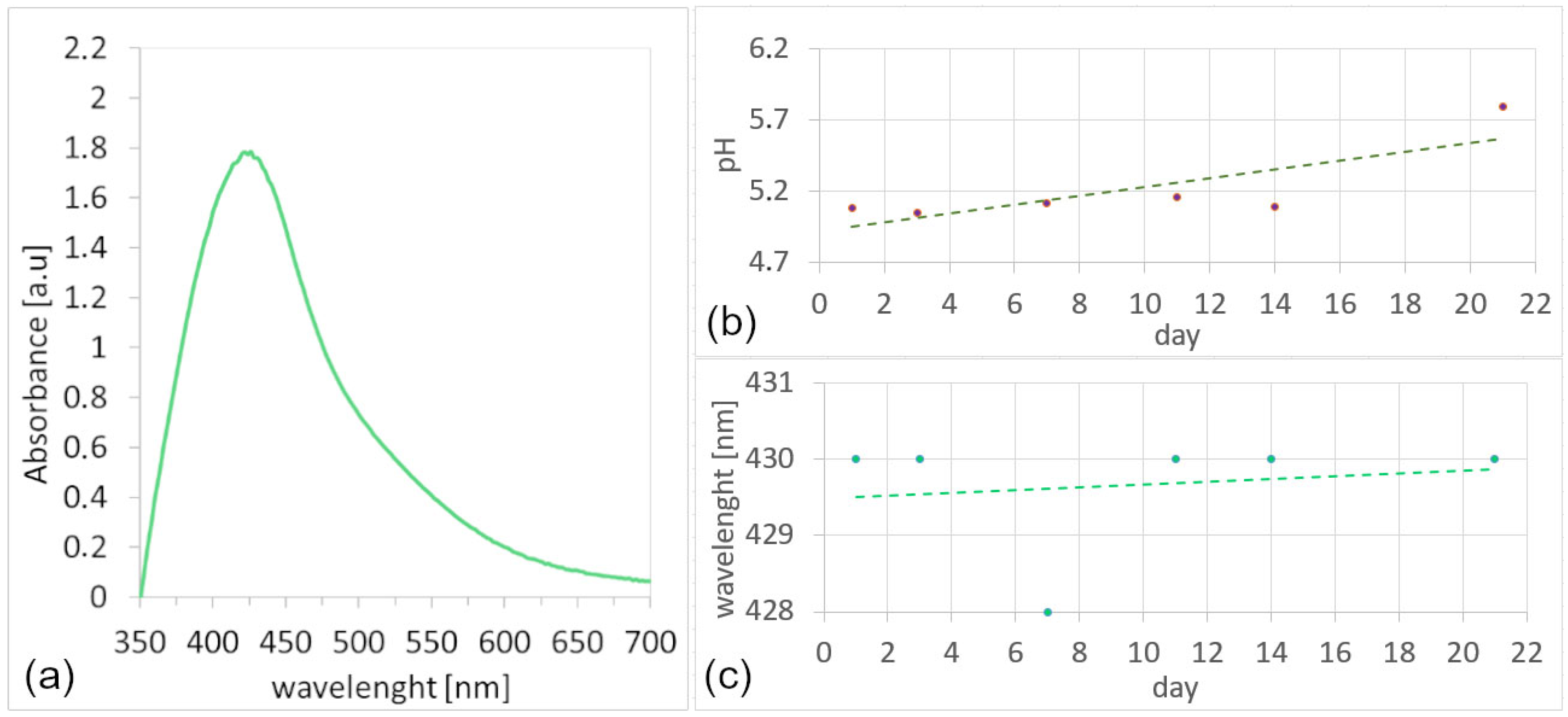

3.1.3. UV-vis Analysis

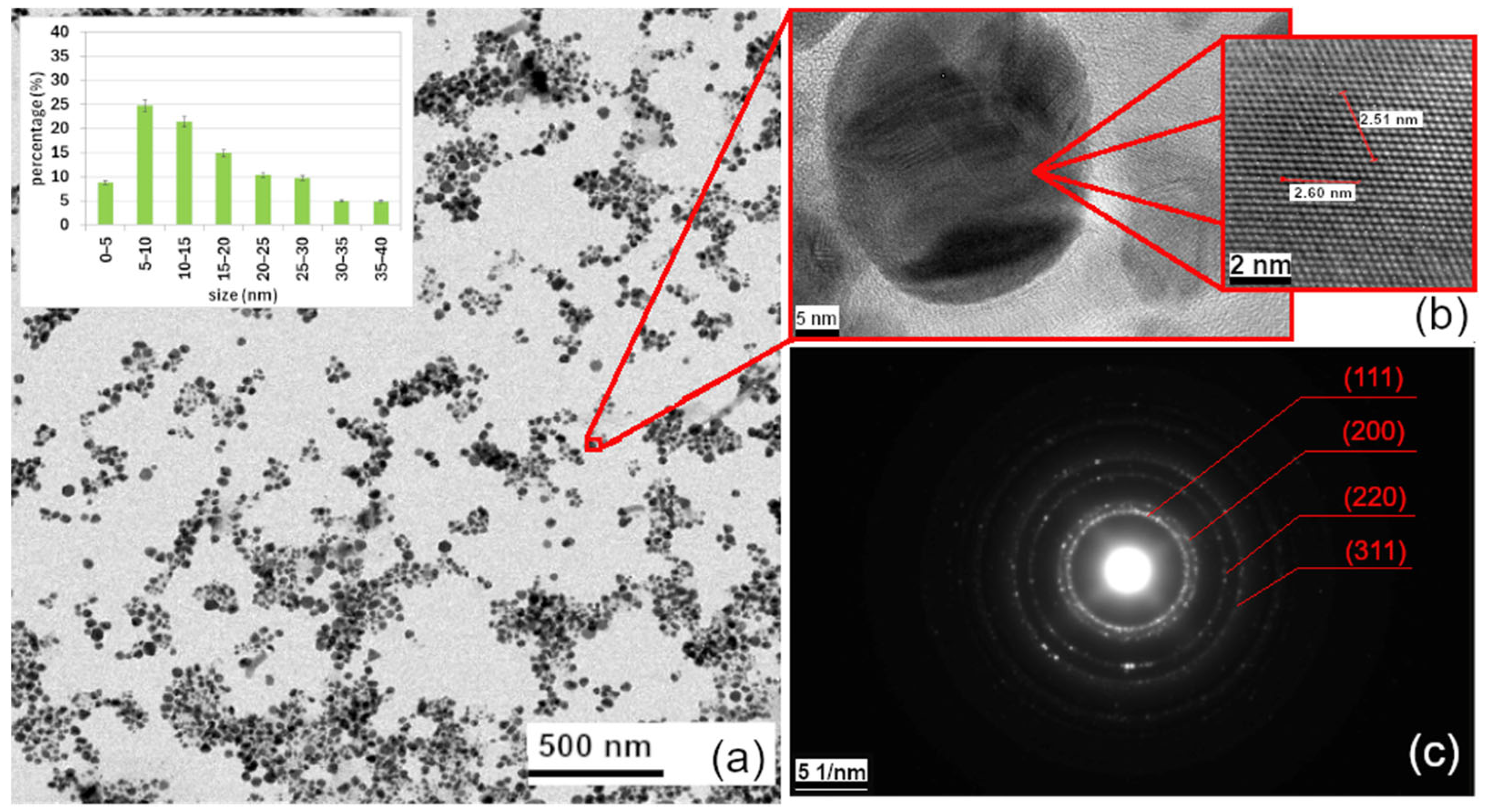

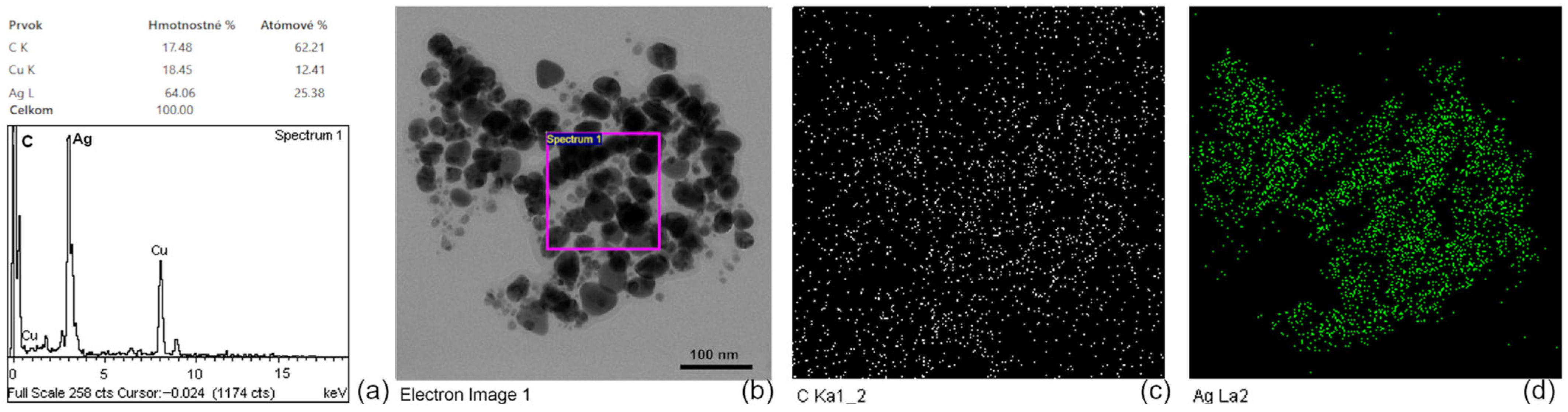

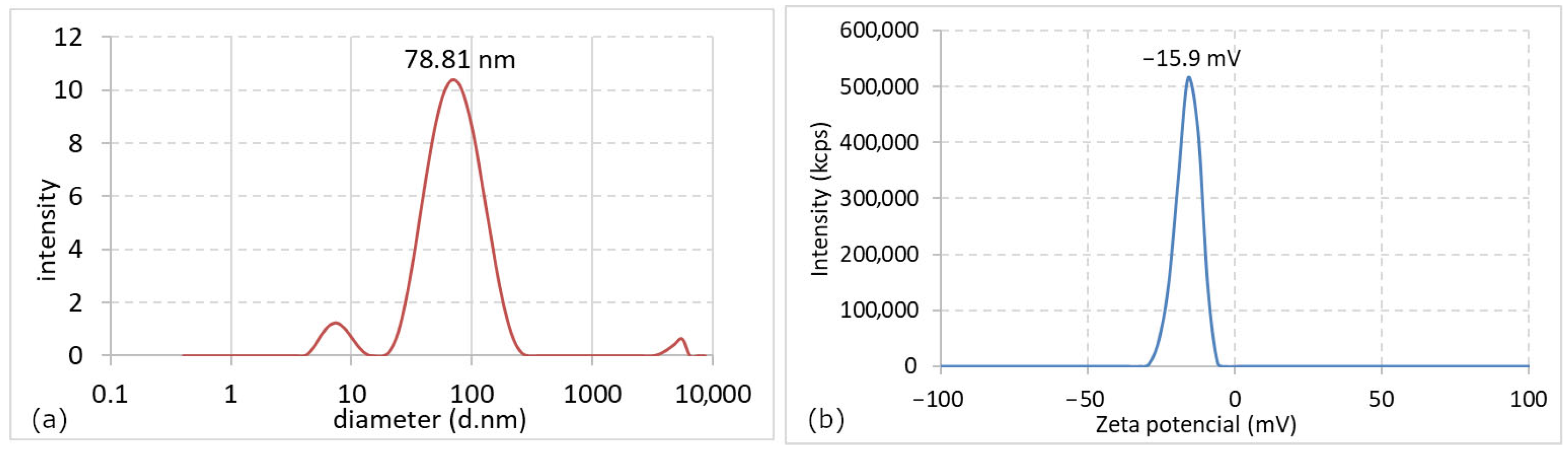

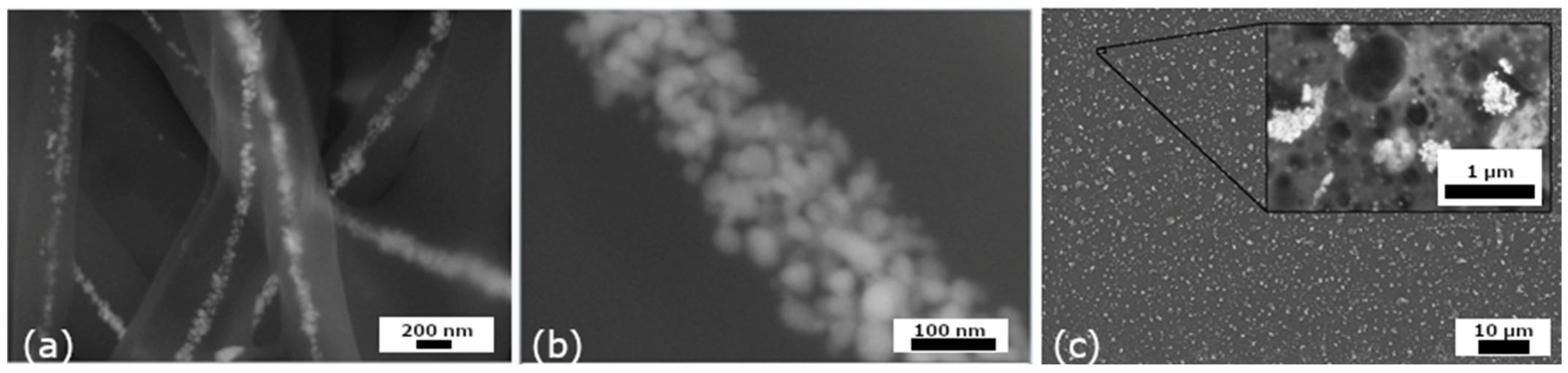

3.1.4. Characterization of AgNPs by TEM, HRTEM, EDX, DLS, and Zeta Potential

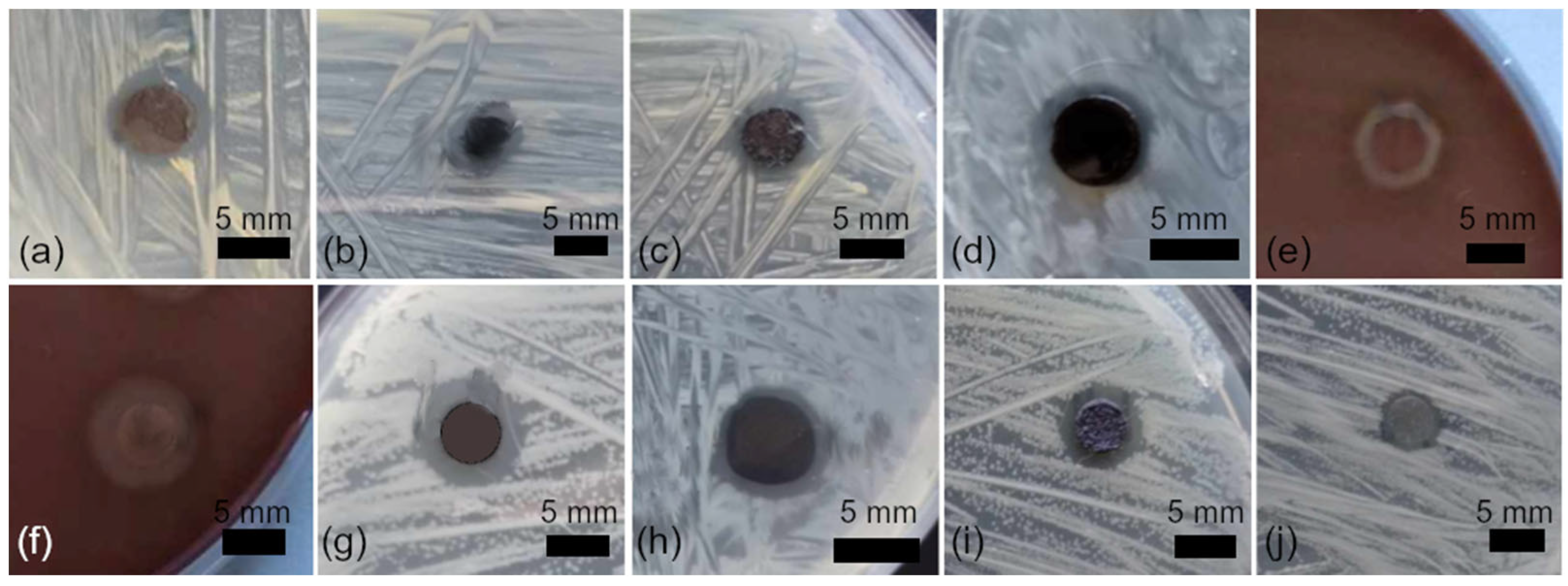

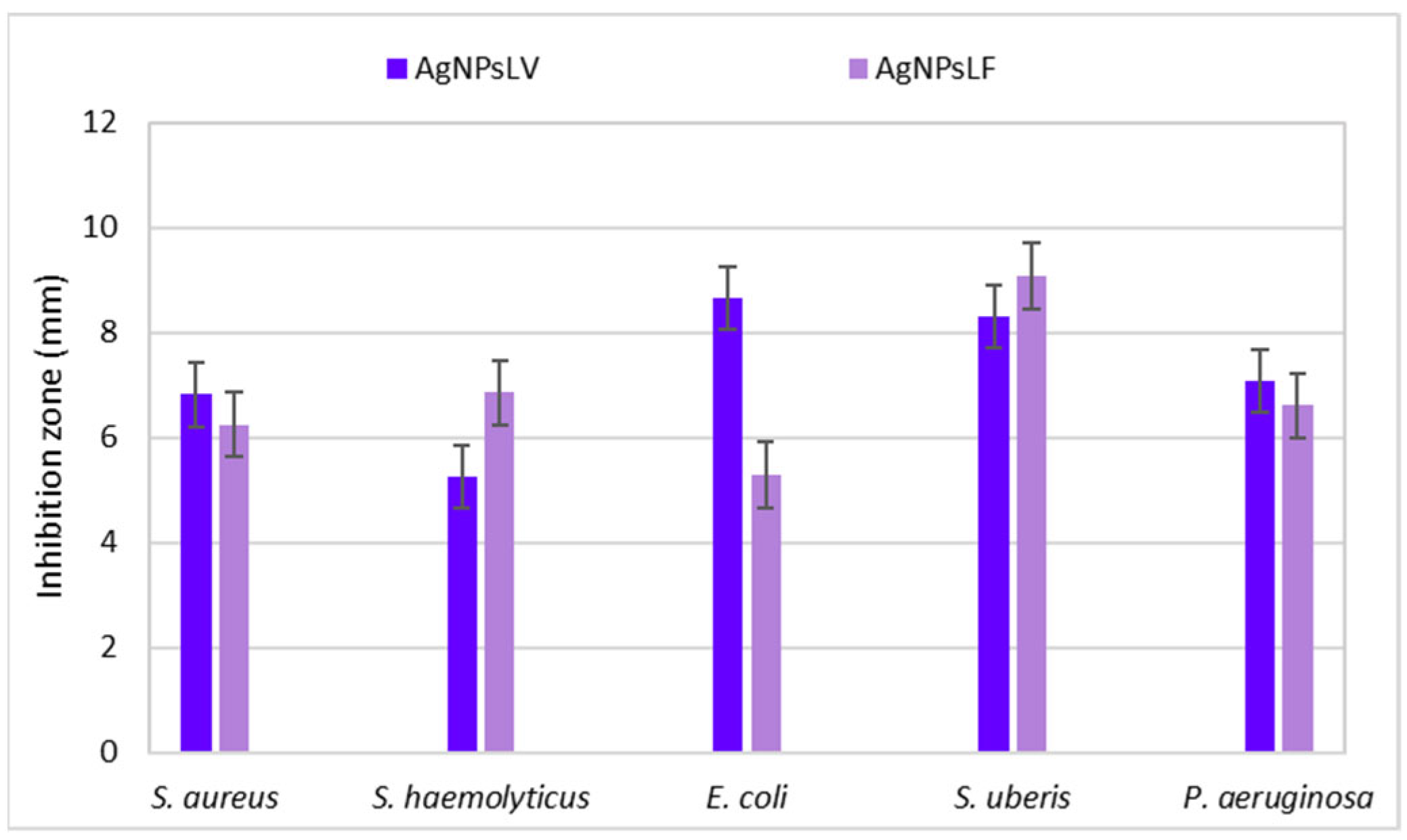

3.1.5. Antibacterial Activity of Colloidal AgNPs

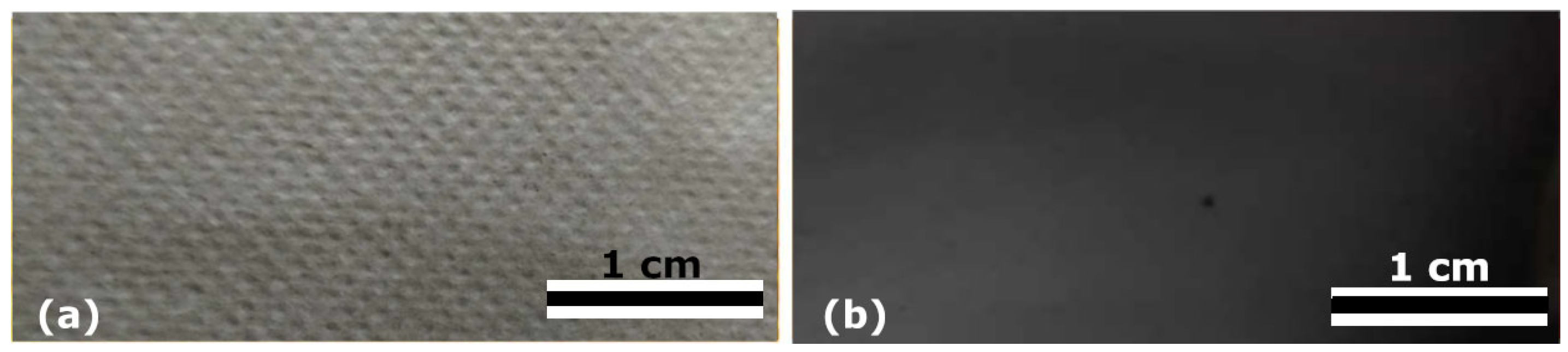

3.2. Analysis of Nanocomposites

3.3. Antibacterial Activity of Nanocomposites

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malik, S.; Muhammad, K.; Waheed, Y. Nanotechnology: A Revolution in Modern Industry. Molecules 2023, 28, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balážová, Ľ.; Babula, P.; Baláž, M.; Bačkorová, M.; Bujňáková, Z.; Briančin, J.; Kurmanbayeva, A.; Sagi, M. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Phytotoxicity on Halophyte from Genus Salicornia. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 130, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khenfouch, M.; Minnis Ndimba, R.; Diallo, A.; Khamlich, S.; Hamzah, M.; Dhlamini, M.S.; Mothudi, B.M.; Baitoul, M.; Srinivasu, V.V.; Maaza, M. Artemisia Herba-Alba Asso Eco-Friendly Reduced Few-Layered Graphene Oxide Nanosheets: Structural Investigations and Physical Properties. Green. Chem. Lett. Rev. 2016, 9, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, C.; Foldbjerg, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Sutherland, D.S.; Autrup, H. Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles-Nanoparticle or Silver Ion? Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 208, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Das, M. Study of Silver Nanoparticle/Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanocomposite. Int. J. Plast. Technol. 2019, 23, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Alam, S.; Amin, U.; Ullah, I.; Muhammad, M.; Ullah, M.; Rehman, A.; Khan, T. Efficient Green Silver Nanoparticles-Antibiotic Combinations against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. AMB Express 2023, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefian, S.; Ghavam, M. Green and environmentally friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial properties from some medicinal plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2024, 24, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdiyev, A.M.; Kon, K.V.; Abamor, E.S.; Bagirova, M.; Rafailovich, M. Coping with Antibiotic Resistance: Combining Nanoparticles with Antibiotics and Other Antimicrobial Agents. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaweeteerawat, C.; Na Ubol, P.; Sangmuang, S.; Aueviriyavit, S.; Maniratanachote, R. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteria Mediated by Silver Nanoparticles. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part. A Curr. Issues 2017, 80, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.S.; Dzurny, D.I.; Dees, W.R.; Qin, N.; Nunez Rodriguez, C.C.; Alt, L.A.; Ellward, G.L.; Best, J.A.; Rudawski, N.G.; Fujii, K.; et al. Silver Nanoparticles Enhance the Efficacy of Aminoglycosides against Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1064095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casals, E.; Gusta, M.F.; Bastus, N.; Rello, J.; Puntes, V. Silver Nanoparticles and Antibiotics: A Promising Synergistic Approach to Multidrug-Resistant Infections. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinowska, R.; Śmigielski, K.B. Composition, Biological Properties and Therapeutic Effects of Lavender (Lavandula angustifolia L). A Review. Herba Pol. 2014, 60, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omanović-Mikličanin, E.; Badnjević, A.; Kazlagić, A.; Hajlovac, M. Nanocomposites: A Brief Review. Health Technol. 2020, 10, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M. Recent Progress and Overview of Nanocomposites. In Nanocomposite Materials-Biomedical and Energy Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plachá, D.; Muñoz-Bonilla, A.; Škrlová, K.; Echeverria, C.; Chiloeches, A.; Petr, M.; Lafdi, K.; Fernández-García, M. Antibacterial Character of Cationic Polymers Attached to Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Singha, N.R. Polymeric Nanocomposite Membranes for next Generation Pervaporation Process: Strategies, Challenges and Future Prospects. Membranes 2017, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, B.; Muñoz, M.; Muraviev, D.N.; Macanás, J. Polymer-Silver Nanocomposites as Antibacterial Materials. Microb. Pathog. Strateg. Combat. Them Sci. Technol. Educ. 2013, 1, 630–640. [Google Scholar]

- Sari Gencag, B.; Kahraman, K.; Ekici, L. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Pomegranate Peel and Their Application in PVA-Based Nanofibers for Coating Minced Meat. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.K.; Ferreira, J.M.F.; Kannan, S. Mechanically Stable Antimicrobial Chitosan-PVA-Silver Nanocomposite Coatings Deposited on Titanium Implants. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 121, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.S.; Fatima, Z.; Hameed, S.; Nidhin, M. Highly Surface Active Anisotropic Silver Nanoparticles as Antimicrobial Agent Against Human Pathogens, Mycobacterium Smegmatis and Candida Albicans. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6, 5466–5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, G.H.; Akyüz, G.; Kaymazlar, E.; Andac, M. An Investigation of Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Turkish Honey Against Pathogenic Bacterial Strains. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavita, K.; Singh, V.K.; Jha, B. 24-Branched Δ5 Sterols from Laurencia Papillosa Red Seaweed with Antibacterial Activity against Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salayová, A.; Bedlovičová, Z.; Daneu, N.; Baláž, M.; Lukáčová Bujňáková, Z.; Balážová, Ľ. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Lavender and Rosemary Extracts and Their Potential Antibacterial Activity. Plants 2021, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Nazir, R.; Shaheen, A.; Saleem, S.; Shahid, M. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts and Their Antimicrobial Activities: A Review. Green Process. Synth. 2021, 10, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezma, A.M.; El-Tantawy, F.; Alqahtani, N.; Mohamed, A.M. FTIR and UV–Vis Studies of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Citrullus colocynthis Leaf Extract. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 1050d2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kora, A.J. Silver Nanoparticles: Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity. In Silver Nanoparticles-Fabrication, Characterization and Applications; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Krähmer, A.; Herwig, N.; Schulz, H.; Hadian, J.; Meiners, T. Variation of Secondary Metabolite Profile of Zataria multiflora Boiss. Populations Linked to Geographic, Climatic, and Edaphic Factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Hmadi, H.; El Mokni, R.; Joshi, R.K.; Ashour, M.L.; Hammami, S. The Impact of Geographical Location on the Chemical Compositions of Pimpinella lutea Desf. Growing in Tunisia. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwu, M.C.; Izah, S.C.; Joshua, M.T. Ecological and Environmental Determinants of Phytochemical Variability in Forest Trees. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 5109–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.N.; Mancini, M.C.; Oliveira, F.C.S.d.; Passos, T.M.; Quilty, B.; Thiré, R.M.d.S.M.; McGuinness, G.B. FTIR Analysis and Quantification of Phenols and Flavonoids of Five Commercially Available Plant Extracts Used in Wound Healing. Matéria 2016, 21, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elemike, E.E.; Onwudiwe, D.C.; Ekennia, A.C.; Katata-Seru, L. Biosynthesis, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Obtained Using Lavandula × Intermedia. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, G.; Poinern, J.; Chapman, P.; Shah, M.; Fawcett, D. Green Biosynthesis of Silver Nanocubes Using the Leaf Extracts from Eucalyptus Macrocarpa Green Biosynthesis of Silver Nanocubes Using the Leaf Extracts from Eucalyptus Macrocarpa. Nano Bull. 2013, 2, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Otibi, F.; Al-Ahaidib, R.A.; Alharbi, R.I.; Al-Otaibi, R.M.; Albasher, G. Antimicrobial Potential of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles by Aaronsohnia Factorovskyi Extract. Molecules 2021, 26, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, C.; Berta, L.; Coman, N.A.; Roşca, I.; Man, A.; Toma, F.; Mocan, A.; Nicolescu, A.; Jakab-Farkas, L.; Biró, D.; et al. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Potential of Silver Nanoparticles Biosynthesized Using the Spruce Bark Extract. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosman, N.S.R.; Harun, N.A.; Idris, I.; Ismail, W.I.W. Eco-Friendly Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) Fabricated by Green Synthesis Using the Crude Extract of Marine Polychaete, Marphysa Moribidii: Biosynthesis, Characterisation, and Antibacterial Applications. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, A.Y. Antimicrobial and Catalytic Activities of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Bay Laurel (Laurus nobilis) Leaves Extract. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 10, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, N.; Devra, V. A kinetic study on the degradation and biodegradability of silver nanoparticles catalyzed methyl orange and textile effluents. Results Chem. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Guo, R.; Cao, X.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Y.; Shen, M.; Zhang, G.; Shi, X. Size-Controlled Synthesis of Dendrimer-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles for X-Ray Computed Tomography Imaging Applications. Polym. Chem. 2010, 1, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Bulut, O.; Some, S.; Mandal, A.K.; Yilmaz, M.D. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Biomolecule-Nanoparticle Organizations Targeting Antimicrobial Activity. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 2673–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Deepalekshmi, S.; Mariappan, P.; Ahamed, R.M.B.; Ali, M.; Al-Maadeed, S.A. (Eds.) Lecture Notes in Bioengineering Polymer Nanocomposites in Biomedical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi, N.; Chowdhury, D. In-Situ and Ex-Situ Chitosan-Silver Nanoparticle Composite: Comparison of Storage/Release and Catalytic Properties. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 4147–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’sakni, N.H.; Alsufyani, T. Part B: Improvement of the Optical Properties of Cellulose Nanocrystals Reinforced Thermoplastic Starch Bio-Composite Films by Ex Situ Incorporation of Green Silver Nanoparticles from Chaetomorpha Linum. Polymers 2023, 15, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, K.; Bhandari, A.; Yadav, K.S. Nanoparticles Incorporated in Nanofibers Using Electrospinning: A Novel Nano-in-Nano Delivery System. J. Control. Release 2022, 350, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorusso, A.B.; Carrara, J.A.; Barroso, C.D.N.; Tuon, F.F.; Faoro, H. Role of Efflux Pumps on Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yontar, A.K.; Çevik, S. Effects of Plant Extracts and Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles on the Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) Nanocomposite Films. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 12043–12060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, S.M.; El-Sayed, G.O.; Mohamed, M.A.; El-Baz, A.M.; Abdel-Aziz, A.A. Fabrication and Characterization of Chitosan/PVA Hydrogels Reinforced with Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles for Antibacterial and Biocompatible Wound Dressing Applications. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehzad, A.; Tariq, F.; Al Saidi, A.K.; Ali Khan, K.; Ali Khan, S.; Alshammari, F.H.; Ul-Islam, M. Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticle-Infused PVA Hydrogels: A Sustainable Solution for Skin Repair. Results Chem. 2025, 17, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mačák, L.; Velgosová, O.; Múdra, E.; Vojtko, M.; Ondrašovičová, S. Sustainable Lavender Extract-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Use in Fabricating Antibacterial Polymer Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020098

Mačák L, Velgosová O, Múdra E, Vojtko M, Ondrašovičová S. Sustainable Lavender Extract-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Use in Fabricating Antibacterial Polymer Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020098

Chicago/Turabian StyleMačák, Lívia, Oksana Velgosová, Erika Múdra, Marek Vojtko, and Silvia Ondrašovičová. 2026. "Sustainable Lavender Extract-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Use in Fabricating Antibacterial Polymer Nanocomposites" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020098

APA StyleMačák, L., Velgosová, O., Múdra, E., Vojtko, M., & Ondrašovičová, S. (2026). Sustainable Lavender Extract-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Use in Fabricating Antibacterial Polymer Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020098