Geometry-Dependent Photonic Nanojet Formation and Arrays Coupling

Abstract

1. Introduction

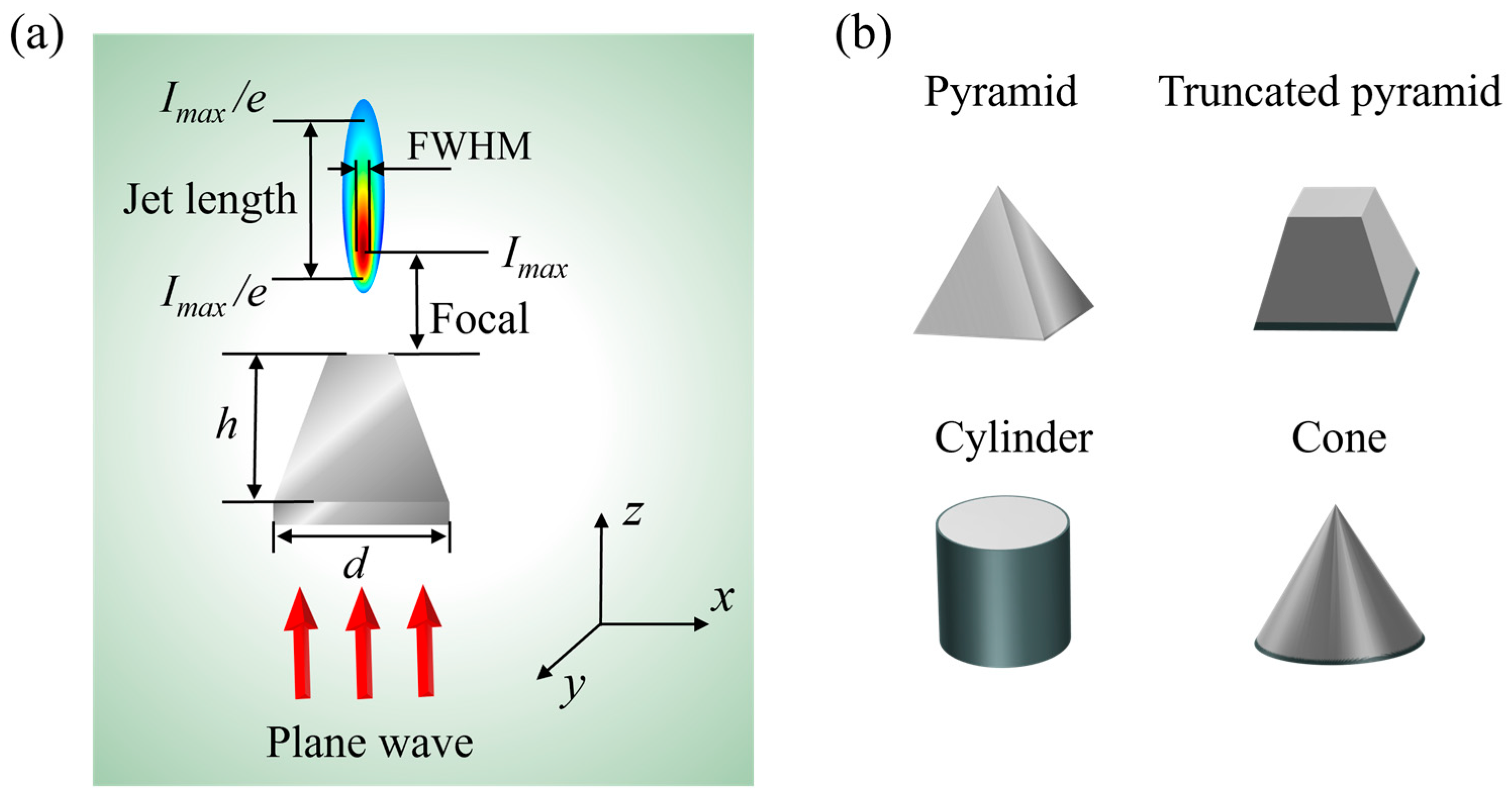

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

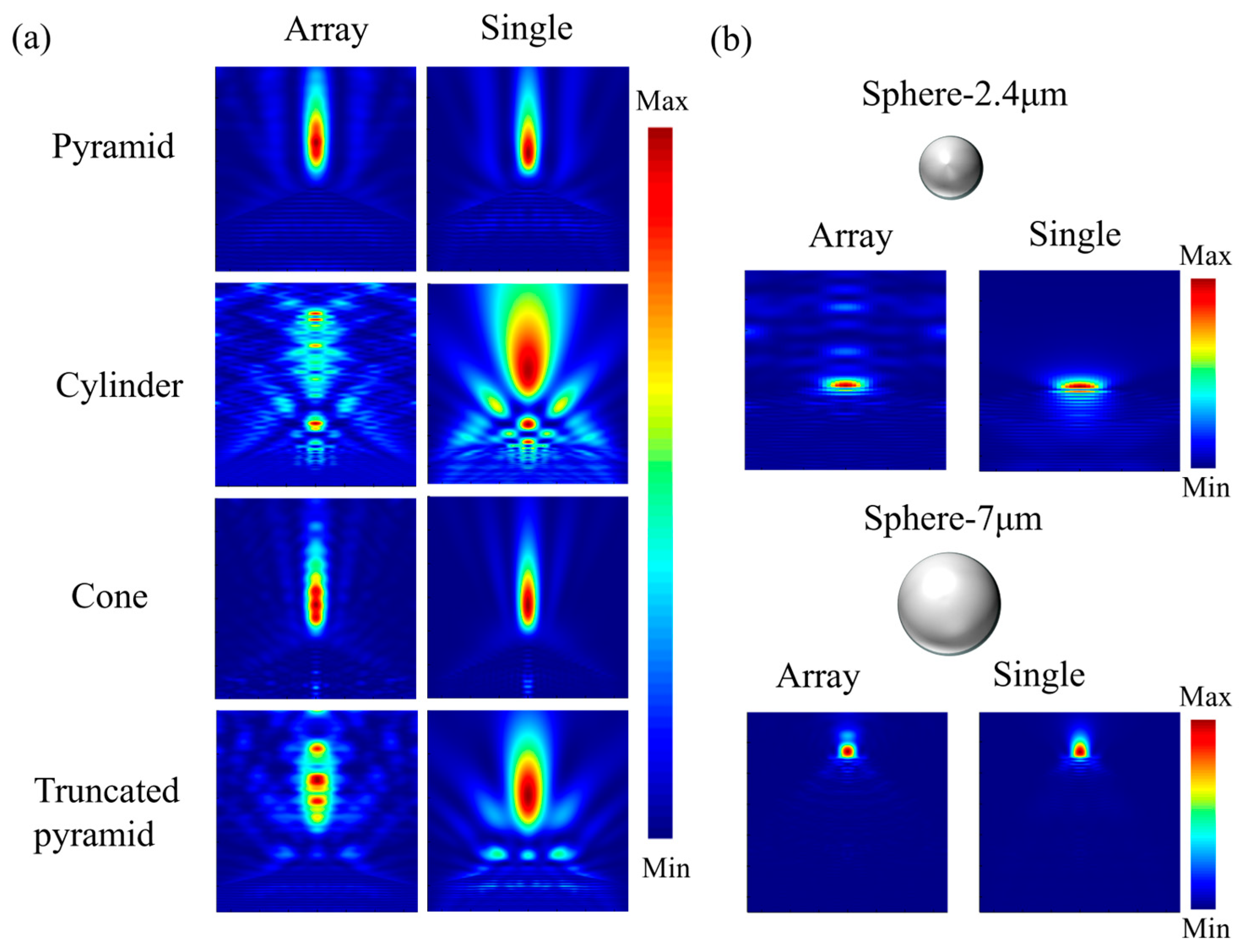

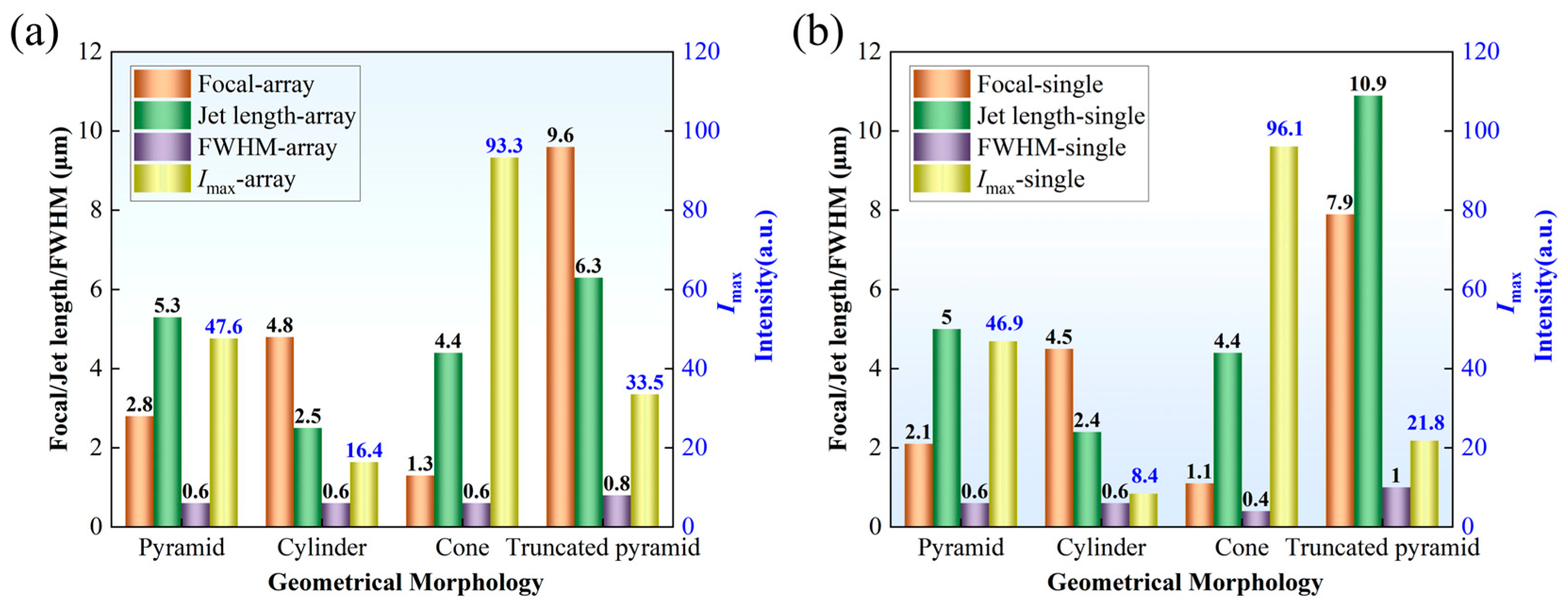

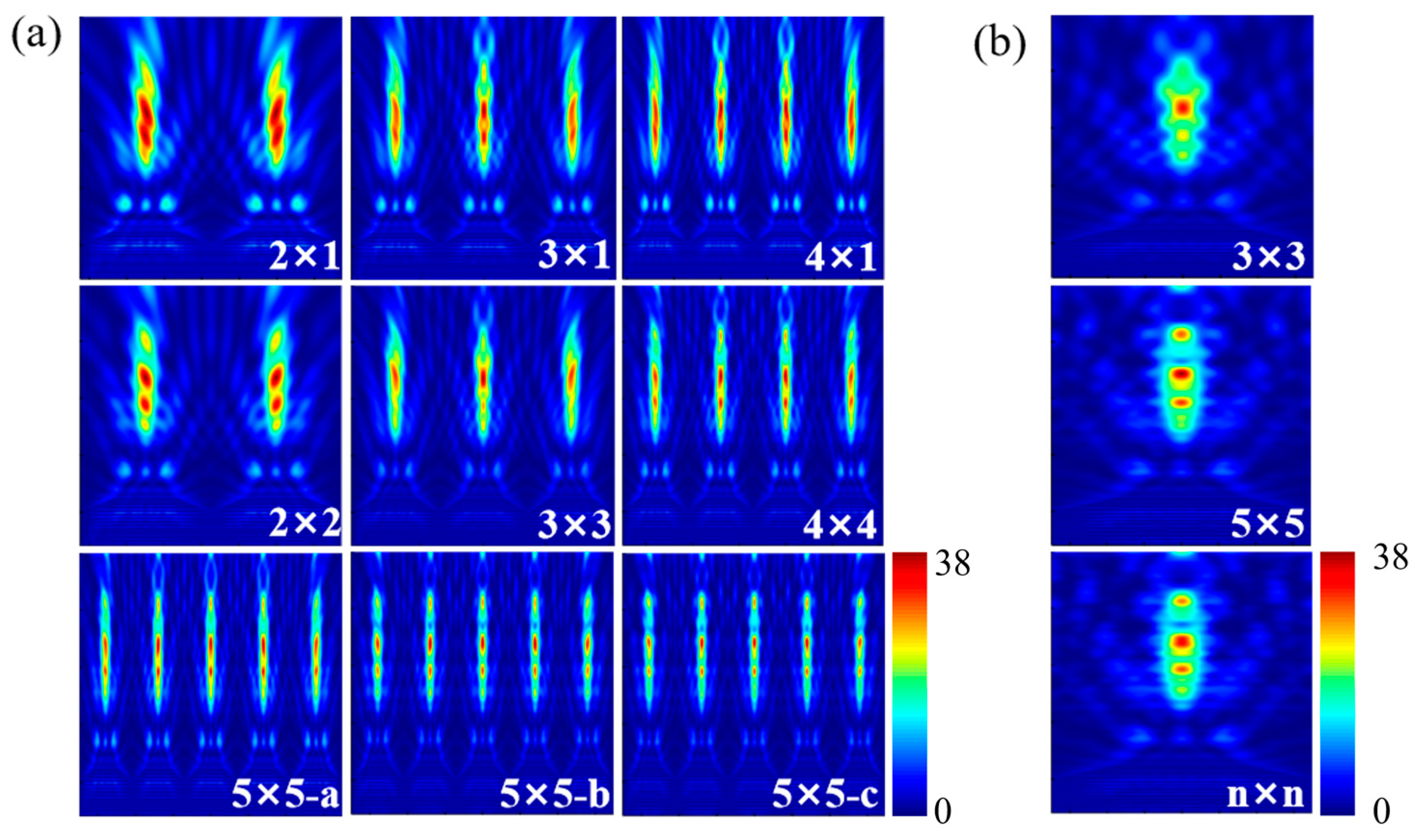

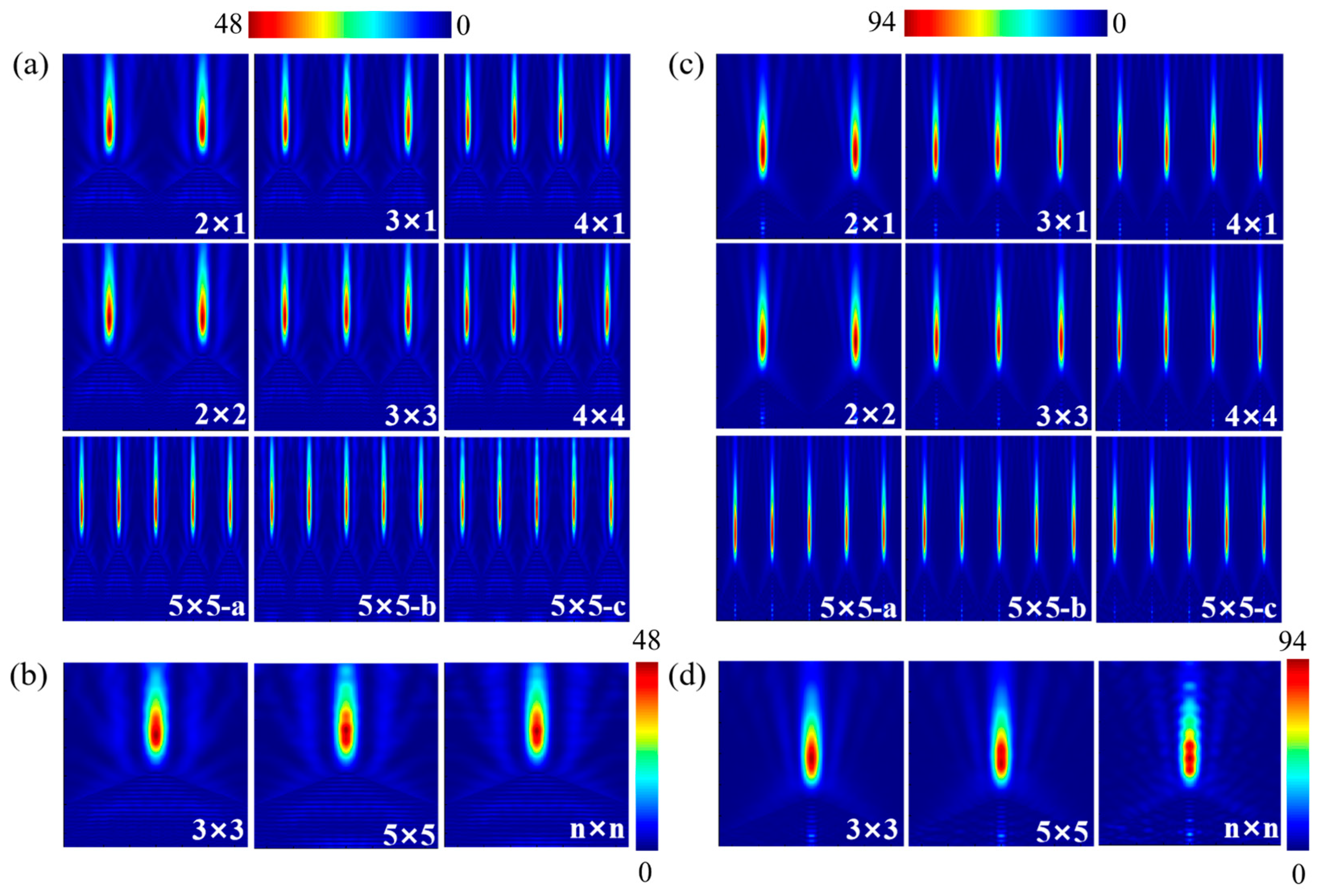

3.1. Differences in Array Coupling of PNJs for Different Geometric Configurations

3.2. PNJs Generated by Different Geometric Structures Under Finite Array Conditions

3.2.1. Cylinder

3.2.2. Ftrustum of a Pyramid

3.2.3. Pyramid Geometry and Cone

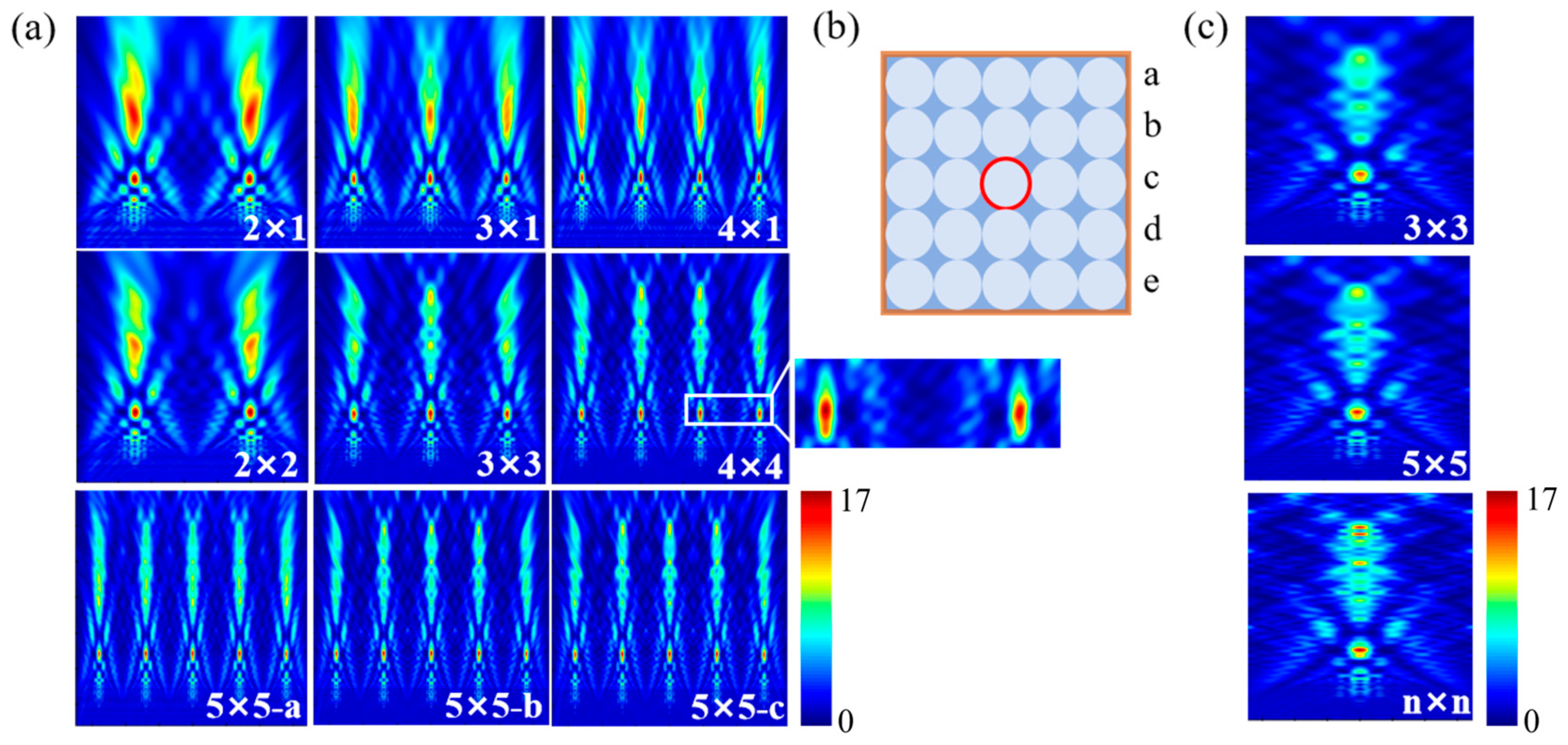

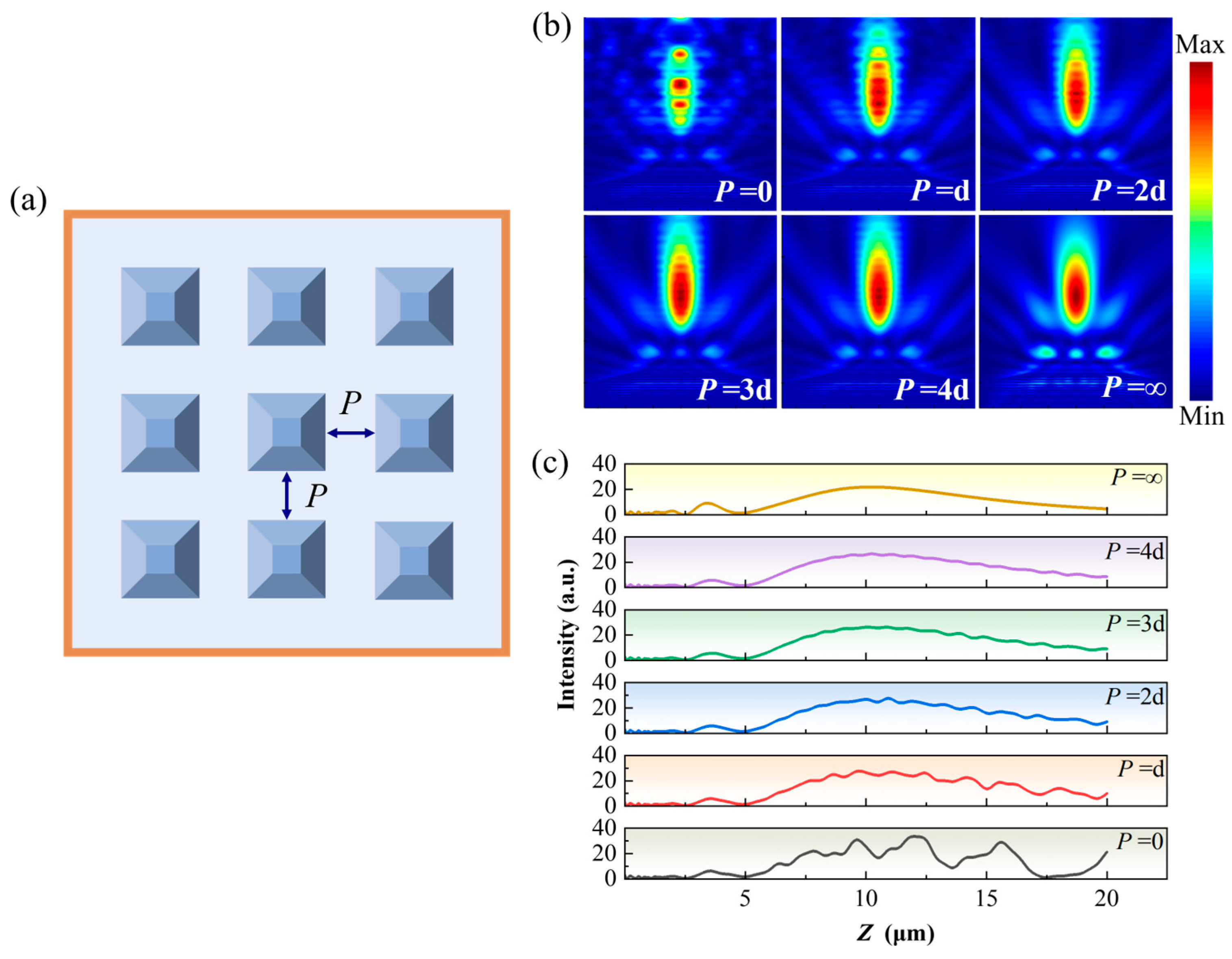

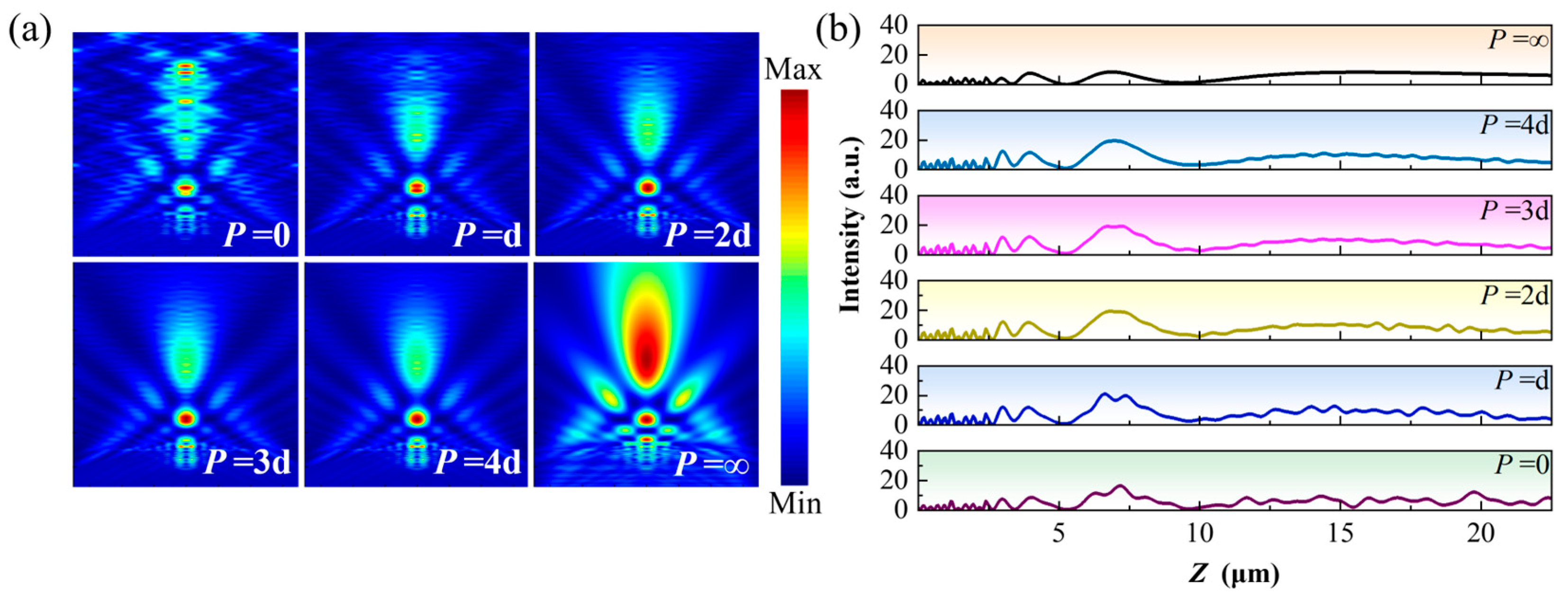

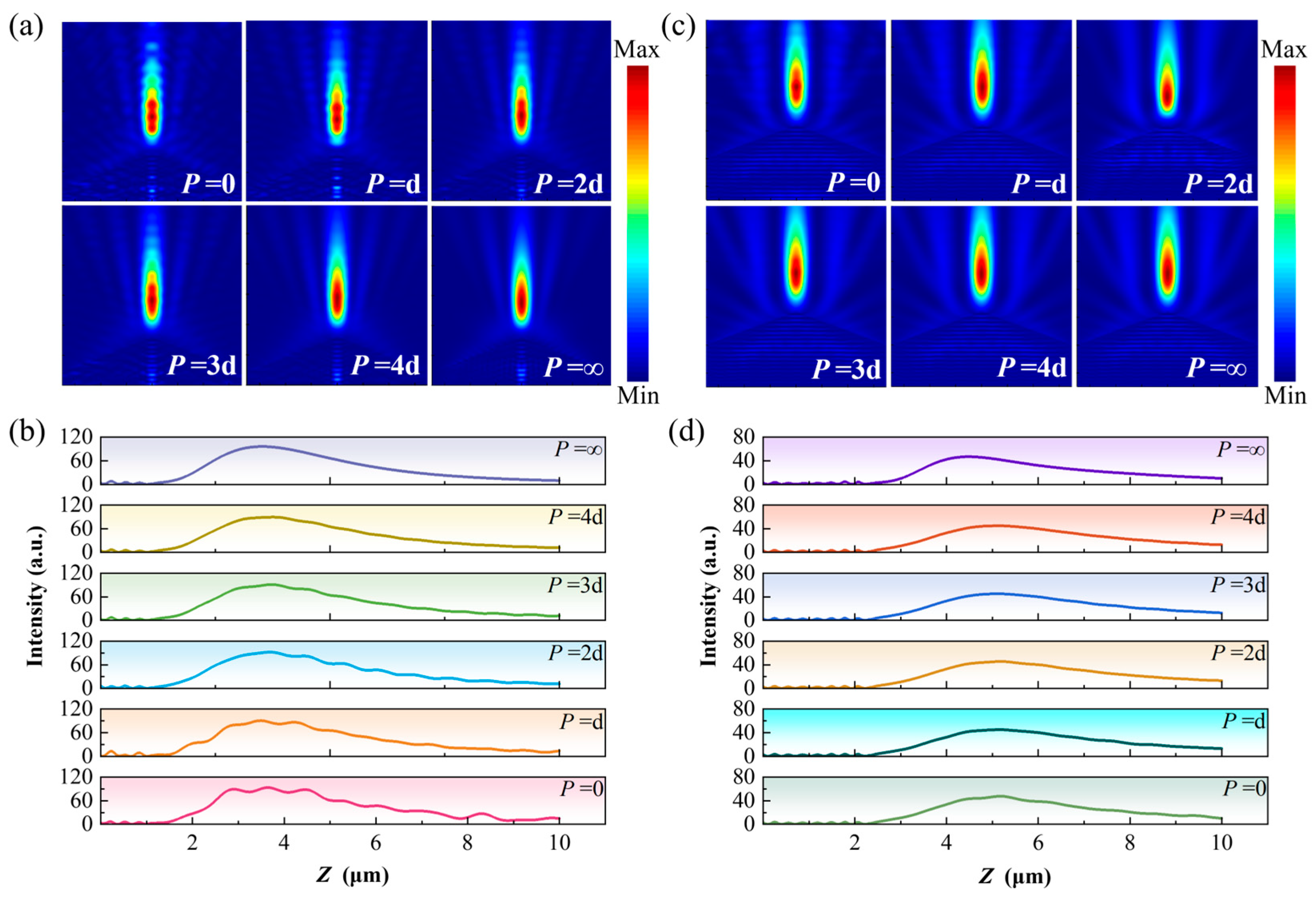

3.3. Regulation of PNJ Coupling by Array Sparsity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PNJ | Photonic nanojet |

| Imax | Maximum light intensity |

References

- Chen, Z.; Taflove, A.; Backman, V. Photonic nanojet enhancement of backscattering of light by nanoparticles: A potential novel visible-light ultramicroscopy technique. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 1214–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itagi, A.V.; Challener, W.A. Optics of photonic nanojets. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2005, 22, 2847–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak Kallepalli, L.N.; Grojo, D.; Charmasson, L.; Delaporte, P.; Utéza, O.; Merlen, A.; Sangar, A.; Torchio, P. Long range nanostructuring of silicon surfaces by photonic nanojets from microsphere Langmuir films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2013, 46, 145102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Scharf, T.; Mühlig, S.; Rockstuhl, C.; Herzig, H.P. Photonic Nanojet engineering: Focal point shaping with scattering phenomena of dielectric microspheres. Proc. SPIE—Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2011, 64, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.X.; Zhou, Y.; Hong, M. Sub-50 nm optical imaging in ambient air with 10× objective lens enabled by hyper-hemi-microsphere. Light Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairagi, K.; Kaur, J.; Gupta, P.; Enoch, S.; Mondal, S.K. On-fiber photonic nanojet enables super-resolution in en face optical coherence tomography and scattering nanoscopy. Commun. Phys. 2025, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; He, Z.; Zhu, G.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Pan, T.; Zhong, S.; Wang, H.; Su, Z.; Ye, L.; et al. Photonic nanojet-regulated soft microalga-robot with controllable deformation and navigation capability. PhotoniX 2024, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Scharf, T.; Stefan, M.; Carsten, R.; Hans, H. Engineering photonic nanojets. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 10206–10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteet, A.; Zhang, X.A.; Nagai, H.; Chang, C.H. Twin photonic nanojets generated from coherent illumination of microscale sphere and cylinder. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 075204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, S.; Pawar, P.; Soundharraj, P.; Yadav, K.; Nilaya, J.P. Effective nanopatterning on metal by optical near-field processing using self-assembled polystyrene monolayer Available to Purchase. J. Laser Appl. 2025, 37, 022007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva, K.A.; Tutov, M.V.; Zhizhchenko, A.Y.; Cherepakhin, A.B.; Leonov, A.A.; Chepak, A.K.; Mironenko, A.Y.; Sergeev, A.A. Ordered photonic nanojet arrays for luminescent optical sensing in liquid and gaseous media. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 378, 133435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.Y.; Sergeeva, K.A.; Tutov, M.V.; Zhizhchenko, A.Y.; Cherepakhin, A.B.; Mironenko, A.Y.; Sergeev, A.A.; Wong, S.K. Experimental Demonstration of Collective Photonic Nanojet Generated by Densely Packed Arrays of Dielectric Microstructures. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Yang, H. Large-Scale Fabrication of Photonic Nanojet Array via Template-Assisted Self-Assembly. Micromachines 2020, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Minin, O.V.; Minin, I.V. First experimental observation of array of photonic jets from saw-tooth phase diffraction grating. Europhys. Lett. 2018, 123, 54003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gašparić, V.; Zopf, D.; Mayerhöfer, T.G.; Popp, J.; Ivanda, M. Microsphere-assisted Raman scattering enhancement by photonic nanojet: The role of the collection system. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 6012–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Tiwari, P.; Upputuri, P.K.; Dantham, V.R. Characteristic parameters of photonic nanojets of single dielectric microspheres illuminated by focused broadband radiation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon-Cheol, K.; Allen, T.; Vadim, B. Quasi one-dimensional light beam generated by a graded-index microsphere. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 3722–3731. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Lin, J.; Jin, P.; Cada, M.; Ma, Y. Photonic nanojet beam shaping by illumination polarization engineering. Opt. Commun. 2019, 456, 124593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minin, I.V.; Minin, O.V.; Pacheco-PeñA, V.; Beruete, M. Localized photonic jets from flat, three-dimensional dielectric cuboids in reflection mode. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 2329–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y. Photonic nanojet shaping of dielectric non-spherical microparticles. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2014, 64, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geints, Y.E.; Minm, I.V.; Panina, E.K.; Zemlyanov, A.A.; Minin, O.V. Comparison of photonic nanojets key parameters produced by nonspherical microparticles. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2017, 49, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geintz, Y.E.; Zemlyanov, A.A.; Panina, E.K. Photonic nanonanojets from nonspherical dielectric microparticles. Russ. Phys. J. 2015, 58, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, V.D.; Stafeev, S.S.; Kotlyar, V.V. Formation of photonic nanojets by two-dimensional microprisms. Opt. Spectrosc. 2024, 131, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Near-Field Nano-Focusing and Nano-Imaging of Dielectric Microparticle Lenses. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 2079–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuaid, W.; Riley, J.A.; Healy, N.; Pacheco-Peña, V. On-fiber high-resolution photonic nanojets via high refractive index dielectrics. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 43678–43690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, H. Single nanoparticle sensing and waveguide applications using photonic nanojets of non-circular microparticles. Optik 2022, 253, 168471. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Su, N.; Zhang, W.; Ye, Z.; Wu, P.; Liu, B. Generation of photonic nanojet using gold film dielectric microdisk structure. Materials 2023, 16, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Kaiwei, L.; Wang, Y. Tunable photonic nanojets from a micro-cylinder with a dielectric nano-layer. Opt.—Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2020, 225, 165878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geints, Y.E.; Zemlyanov, A.A.; Panina, E.K. Microaxicon-generated photonic nanojets. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2015, 32, 1570–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.; Mukharjee, S.; Saha, A. Process engineering study of photonic nanojet from highly intense to higher propagation using FDTD method. Optik 2016, 127, 8836–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, R.; Gong, S.; Yang, L.; Yang, L.; Wei, B.; Zhu, Z.; Mitri, F.G. Curved photonic nanojet generated by a rotating cylinder. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, G.; Zhou, R.; Chen, Z.; Xu, H.; Hong, M. Super-long photonic nanojet generated from liquid-filled hollow microcylinder. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po-Hung, L.L.; Hung, T.Y.; Chen, W.Y.; Chung, H.J.; Cheng, C.H.; Chang, T.L.; Chen, Y.; Minin, O.V.; Minin, I.V.; Liu, C. Direct laser micro-drilling of high-quality photonic nanojet achieved by optical fiber probe with microcone-shaped tip. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2025, 131, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Kong, J.A.N.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.B.; Cheng, C.H.; Liu, C. Biological cell trapping and manipulation of a photonic nanojet by a specific microcone-shaped optical fiber tip. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geints, Y.E.; Zemlyanov, A.A.; Panina, E.K. Characteristics of photonic jets from microcones. Opt. Spectrosc. 2015, 119, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Xi, Y.; Yang, P.; Sun, X.; Li, S.; Lin, D.; Zhou, S. Novel Bilayer Micropyramid Structure Photonic Nanojet for Enhancing a Focused Optical Field. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eti, N.; Giden, I.H.; Hayran, Z.; Rezaei, B.; Kurt, H. Manipulation of photonic nanojet using liquid crystals for elliptical and circular core-shell variations. J. Mod. Opt. 2017, 64, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, L.V.; Shen, J. Ultralong photonic nanojet formed by a two-layer dielectric microsphere. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 4120–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Ma, H.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, G.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, P. Temperature controlled switchable dual-mode multi-bands terahertz metasurface perfect absorber and its application in biosensing. Phys. Lett. A 2025, 558, 130907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Qian, F.; Wang, Y.; Minin, I.V.; Minin, O.V. Photonic hook generation under an electric dipole from a dielectric micro-cylinder. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2024, 323, 109052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; De-Long, Z.; Hua, P. Array of photonic hooks generated by multi-dielectric structure. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 157, 108673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Yao, H.; Chi, T.; Cheng, H.; Pang, T.; Lu, Y.; Liu, N. Analysis of the impact of edge diffraction on the manipulation of photonic nanojets and photonic hooks using an energy-based model in diffraction-based structures. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2024, 57, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.; Zhang, P.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H. Inflection point: A perspective on photonic nanojets. Photonics Res. 2021, 9, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geints, Y.; Zemlyanov, A.; Panina, E. Peculiarities of the formation of an ensemble of photonic nanojets by a micro-assembly of conical particles. Quantum Electron. 2019, 49, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Array Numbers | Focal/(μm) | Jet Length/(μm) | FWHM/(μm) | Imax/(a.u.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 | 4.75 | 2.94 | 0.56 | 13.86 |

| 5 × 5 | 4.8 | 2.63 | 0.56 | 15.19 |

| n × n | 4.75 | 2.5 | 0.56 | 16.42 |

| Array Numbers | Focal/(μm) | Jet Length/(μm) | FWHM/(μm) | Imax/(a.u.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 | 9.33 | 9.5 | 0.84 | 33.22 |

| 5 × 5 | 9.8 | 5.96 | 0.84 | 37.87 |

| n × n | 9.6 | 6.3 | 0.84 | 33.46 |

| Array Numbers | Focal/(μm) | Jet Length/(μm) | FWHM/(μm) | Imax/(a.u.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 | 2.5 | 4.74 | 0.62 | 47.72 |

| 5 × 5 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 0.62 | 47.12 |

| n × n | 2.75 | 5.3 | 0.62 | 47.56 |

| Array Numbers | Focal/(μm) | Jet Length/(μm) | FWHM/(μm) | Imax/(a.u.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 × 3 | 1.3 | 4.45 | 0.55 | 92.43 |

| 5 × 5 | 0.95 | 4.64 | 0.55 | 90.212 |

| n × n | 1.25 | 4.35 | 0.55 | 93.2883 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, Z.; Ge, S.; Shen, L.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, J.; Xi, Y.; Liu, W. Geometry-Dependent Photonic Nanojet Formation and Arrays Coupling. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020136

Sun Z, Ge S, Shen L, Li J, Xu S, Zhang J, Xi Y, Liu W. Geometry-Dependent Photonic Nanojet Formation and Arrays Coupling. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020136

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Zehua, Shaobo Ge, Lujun Shen, Junyan Li, Shibo Xu, Jin Zhang, Yingxue Xi, and Weiguo Liu. 2026. "Geometry-Dependent Photonic Nanojet Formation and Arrays Coupling" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020136

APA StyleSun, Z., Ge, S., Shen, L., Li, J., Xu, S., Zhang, J., Xi, Y., & Liu, W. (2026). Geometry-Dependent Photonic Nanojet Formation and Arrays Coupling. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020136