In Situ Growth of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Within Porous Silicon Carbide (p-SiC) for Constructing Hierarchical Porous Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

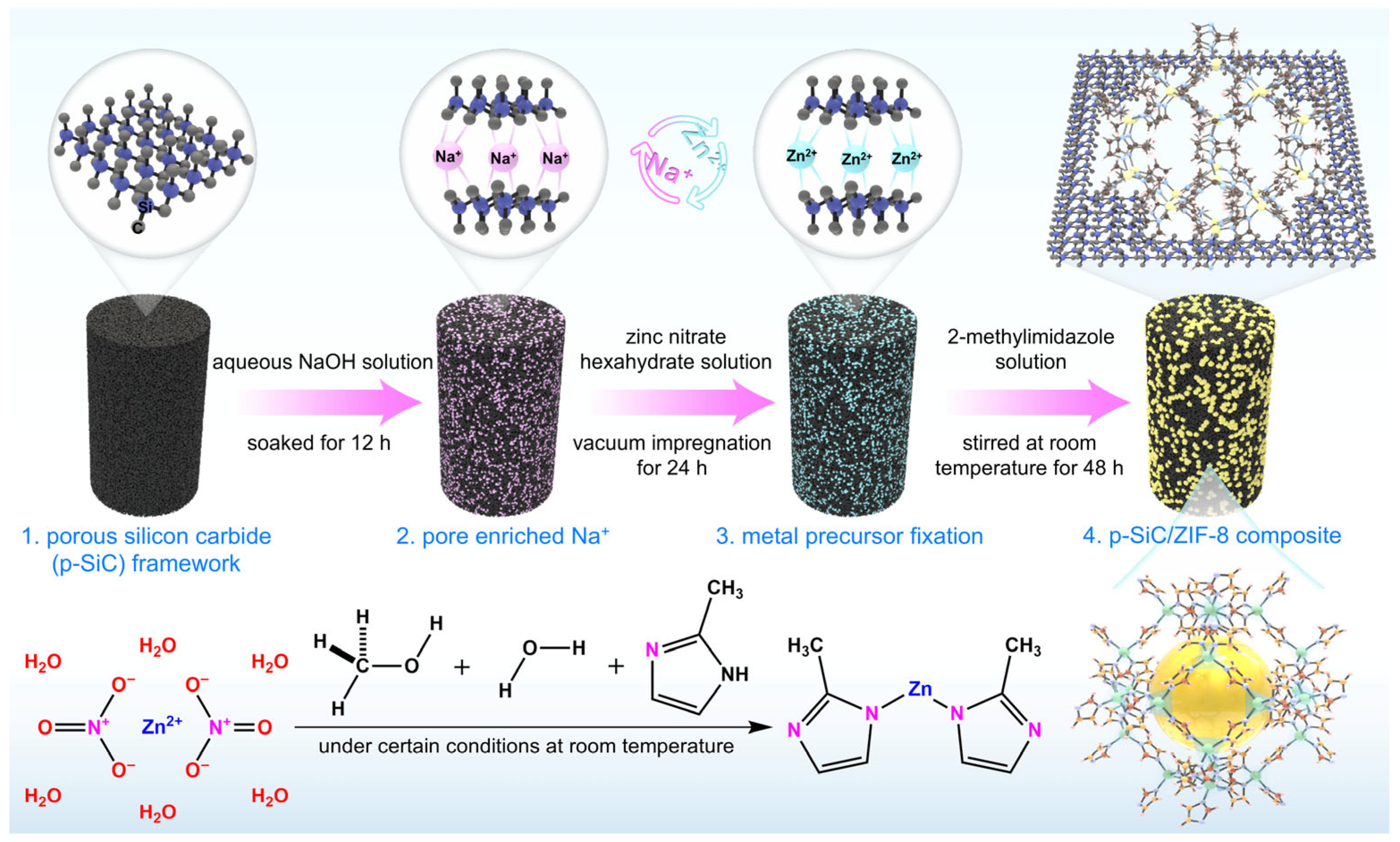

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Preparation of ZIF-8

2.3. Preparation of ZIF-8/p-SiC Composites

2.4. Characterizations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Discussion of System Selection

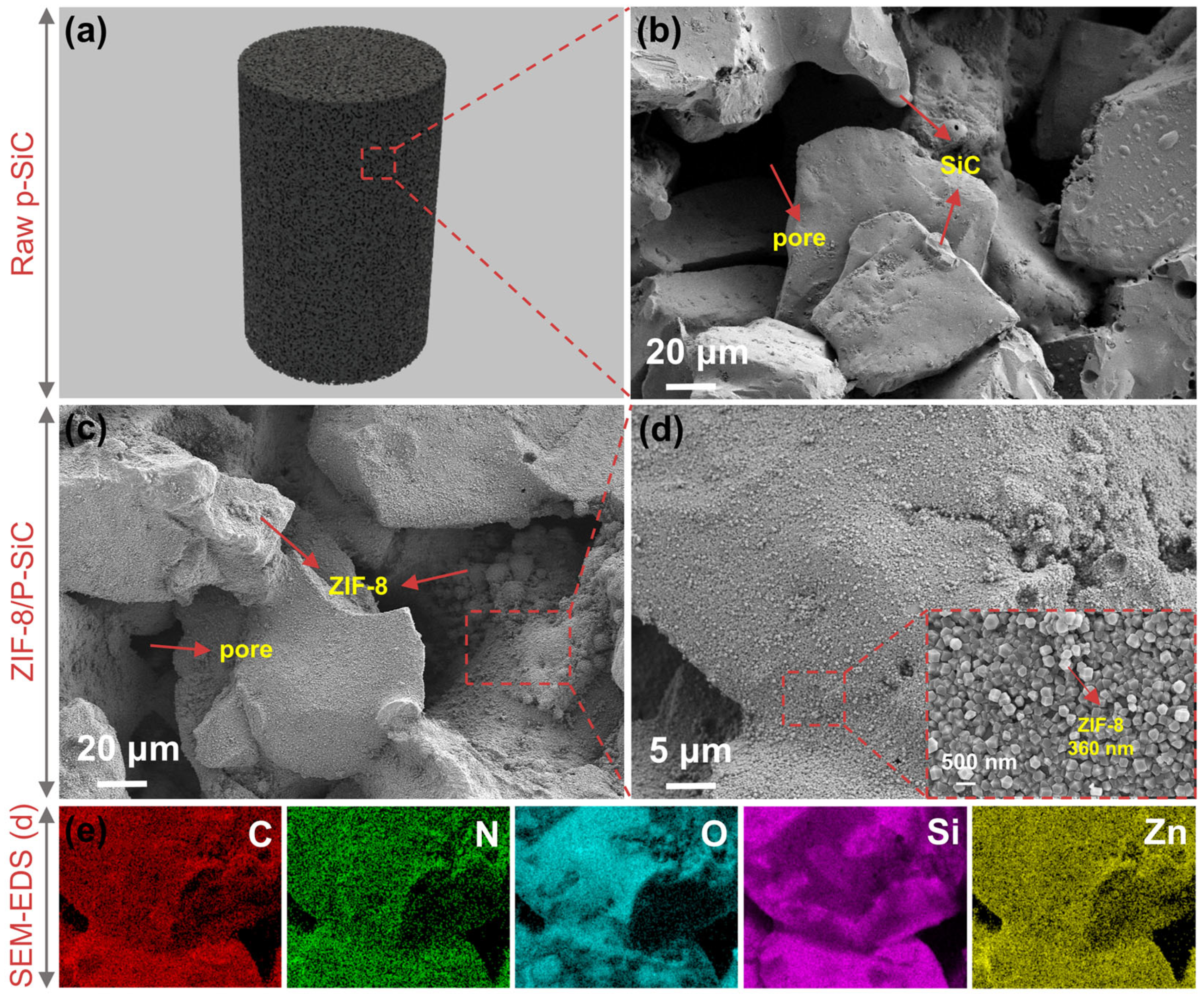

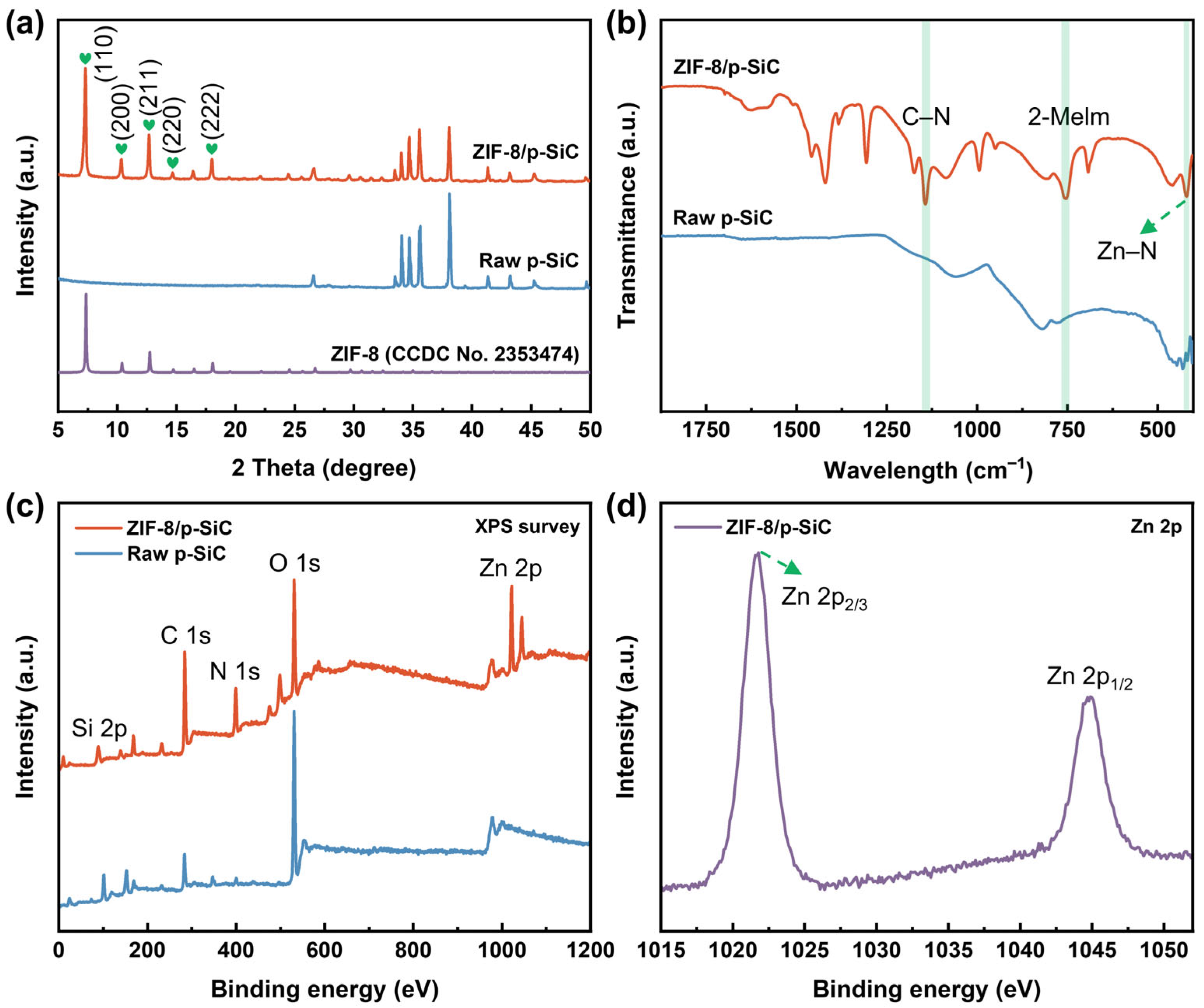

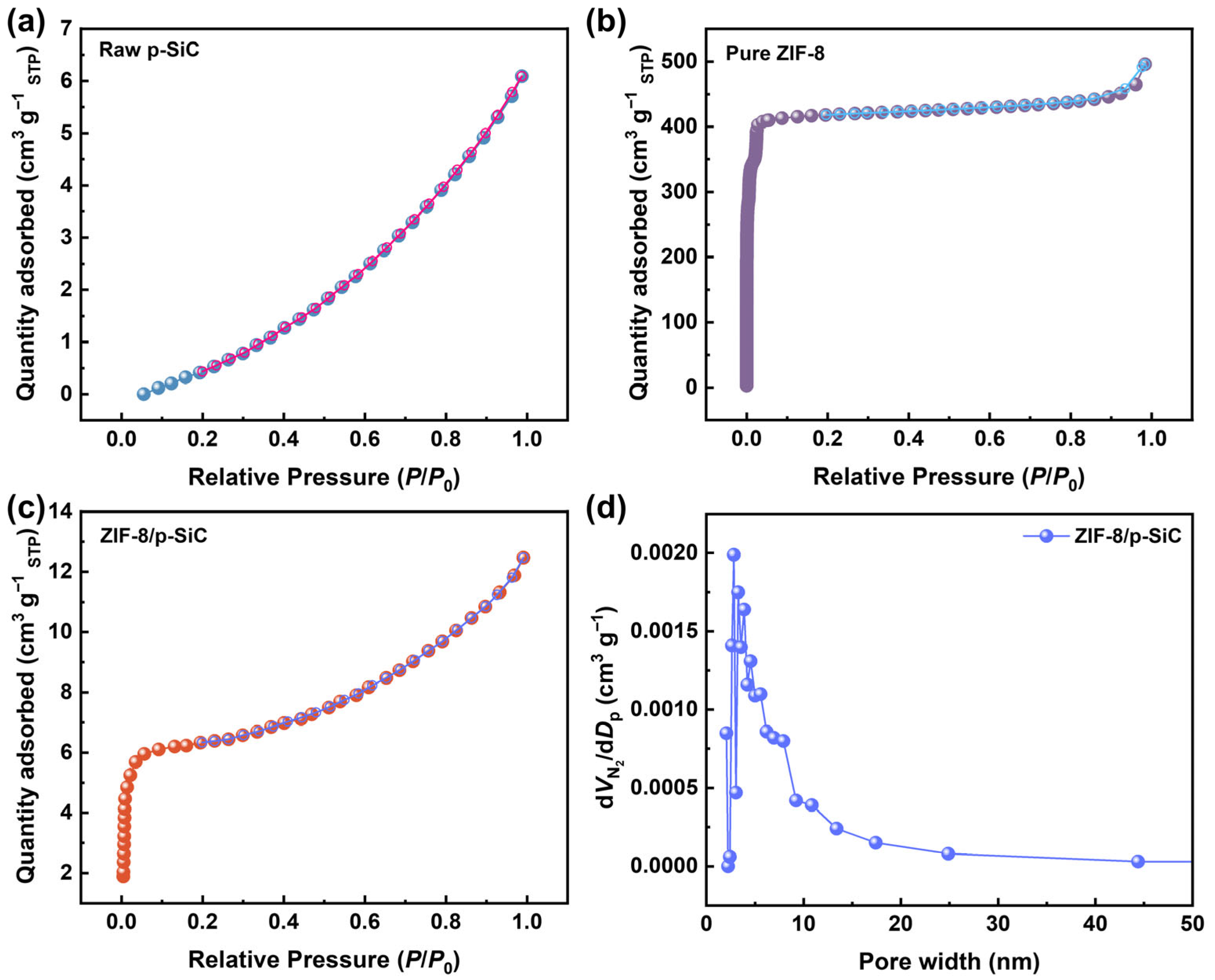

3.2. Composition and Structure

3.3. Assessment of CO2 Adsorption Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaghi, O.M.; Li, G.; Li, H. Selective binding and removal of guests in a microporous metal–organic framework. Nature 1995, 378, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Yan, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.C.; Jiang, H.L. Metal–organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: Synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12278–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, G.; Park, I.H.; Medishetty, R.; Vittal, J.J. Two-dimensional metal-organic framework materials: Synthesis, structures, properties and applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 3751–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Shen, L.; Wang, B.; Lu, X.; Raza, S.; Xu, J.; Li, B.; Lin, H.; Chen, B. Environmental applications of metal–organic framework-based three-dimensional macrostructures: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 2208–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, X.; Kang, Z.; Liu, X.; Sun, D. Isoreticular chemistry within metal–organic frameworks for gas storage and separation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 443, 213968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Flaig, R.W.; Jiang, H.L.; Yaghi, O.M. Carbon capture and conversion using metal–organic frameworks and MOF-based materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 2783–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.D.; Zhao, M. Incorporation of molecular catalysts in metal–organic frameworks for highly efficient heterogeneous catalysis. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgopolova, E.A.; Rice, A.M.; Martin, C.R.; Shustova, N.B. Photochemistry and photophysics of MOFs: Steps towards MOF-based sensing enhancements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4710–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Walden, M.; Ettlinger, R.; Kiessling, F.; Gassensmith, J.J.; Lammers, T.; Wuttke, S.; Peña, Q. Biomedical metal–organic framework materials: Perspectives and challenges. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2308589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Dyosiba, X.; Musyoka, N.M.; Langmi, H.W.; Mathe, M.; Liao, S. Review on the current practices and efforts towards pilot-scale production of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 352, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaj, M.; Bentz, K.C.; Ayala, S., Jr.; Palomba, J.M.; Barcus, K.S.; Katayama, Y.; Cohen, S.M. MOF-polymer hybrid materials: From simple composites to tailored architectures. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8267–8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A.; Maji, T.K. Integration of metal–organic frameworks and clay toward functional composite materials. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Han, J.; Duan, G.; Chen, Y.; He, S.; Mei, C.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, K. When MOFs meet wood: From opportunities toward applications. Chem 2022, 8, 2342–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhao, X.; Webb, E.; Xu, G.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Advances in metal–organic framework-based hydrogel materials: Preparation, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 2092–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Meng, Q.; Shen, C.; Zhang, G. Metal based gels as versatile precursors to synthesize stiff and integrated MOF/polymer composite membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 20345–20351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, B. Challenges and recent advances in MOF–polymer composite membranes for gas separation. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuci, G.; Liu, Y.; Rossin, A.; Guo, X.; Pham, C.; Giambastiani, G.; Pham-Huu, C. Porous silicon carbide (SiC): A chance for improving catalysts or just another active-phase carrier? Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10559–10665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Lucio, M.D.S.; Kultayeva, S.; Kim, Y.W. Effect of pore size on the flexural strength of porous silicon carbide ceramics. Open Ceram. 2024, 17, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xue, M.; Ke, C.; Luo, Y.; Yin, Z.; Xie, C.; Zhang, F.; Xing, Y. SiC-enhanced polyurethane composite coatings with excellent anti-fouling, mechanical, thermal, chemical properties on various substrates. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 168, 106909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, B.; Falcone, G. Carbon capture and sequestration versus carbon capture utilisation and storage for enhanced oil recovery. Acta Geotech. 2014, 9, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liao, G.; Fan, R.; Mao, R.; Hou, X.; Li, N.; He, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, L. Multiscale NMR Characterization in Shale: From Relaxation Mechanisms to Porous Media Research Frontiers. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 5777–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravillon, J.; Nayuk, R.; Springer, S.; Feldhoff, A.; Huber, K.; Wiebcke, M. Controlling zeolitic imidazolate framework nano-and microcrystal formation: Insight into crystal growth by time-resolved in situ static light scattering. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 2130–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, A.; Briquet, L.; Malankowska, M.; Massingberd-Mundy, F.; Rudić, S.; Hyde, T.L.; Cavaye, H.; Coronas, J.; Poulston, S.; Johnson, T. Understanding the ZIF-L to ZIF-8 transformation from fundamentals to fully costed kilogram-scale production. Commun. Chem. 2022, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, M.A.M.; Farmer, W.; Hsiao, C.L.; Dos Santos, R.B.; Hultman, L.; Birch, J.; Ankit, K.; Gueorguiev, G.K. Density functional theory-fed phase field model for semiconductor nanostructures: The case of self-induced core–shell InAlN nanorods. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 4717–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troyano, J.; Carné-Sánchez, A.; Avci, C.; Imaz, I.; Maspoch, D. Colloidal metal–organic framework particles: The pioneering case of ZIF-8. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 5534–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugin, N.; Villajos, J.A.; Feldmann, I.; Emmerling, F. Mix and wait—A relaxed way for synthesizing ZIF-8. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 8940–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, K.; Puértolas, B.; Adobes-Vidal, M.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Traber, J.; Burgert, I.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Keplinger, T. Green synthesis of hierarchical metal–organic framework/wood functional composites with superior mechanical properties. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Wu, Y.; Jin, X.; Wu, J.; Gan, L.; Li, J.; Cai, L.; Liu, C.; Xia, C. Creation of wood-based hierarchical superstructures via in situ growth of ZIF-8 for enhancing mechanical strength and electromagnetic shielding performance. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2400074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Zhu, J.; Deng, W.; Zhu, J.; He, D. Preparation and adsorption performance study of graphene quantum dots@ ZIF-8 composites for highly efficient removal of volatile organic compounds. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhao, L.; Lai, Z. Rapid synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanocrystals in an aqueous system. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2071–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.R.; Wei, Y.; Chang, M.; Zou, H.; Wang, J.X. Size-controlled synthesis of ZIF-8 nanoparticles by high gravity technology for enhanced tetracycline adsorption. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Albo, P.; Ferreira, T.J.; Martins, C.F.; Alves, V.; Esteves, I.A.; Cunha-Silva, L.; Kumakiri, I.; Crespo, J.; Neves, L.A. Impact of ionic liquid structure and loading on gas sorption and permeation for ZIF-8-based composites and mixed matrix membranes. Membranes 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Dai, Y.; Dong, C.; Yang, X.; Xi, Y. Zeolite imidazolate framework (ZIF)-based mixed matrix membranes for CO2 separation: A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zhu, G. Microporous Materials for Separation Membranes; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon, V.J.; Xu, J.; Reimer, J.A. Solid-state NMR investigations of carbon dioxide gas in metal–organic frameworks: Insights into molecular motion and adsorptive behavior. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 10033–10048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|

| Raw p-SiC | −25.30 ± 2.75 mV |

| Pretreated p-SiC | −48.60 ± 1.20 mV |

| Element | Weight Percentage (wt%) |

|---|---|

| C | 33.70 |

| N | 7.16 |

| O | 22.91 |

| Si | 33.02 |

| Zn | 3.21 |

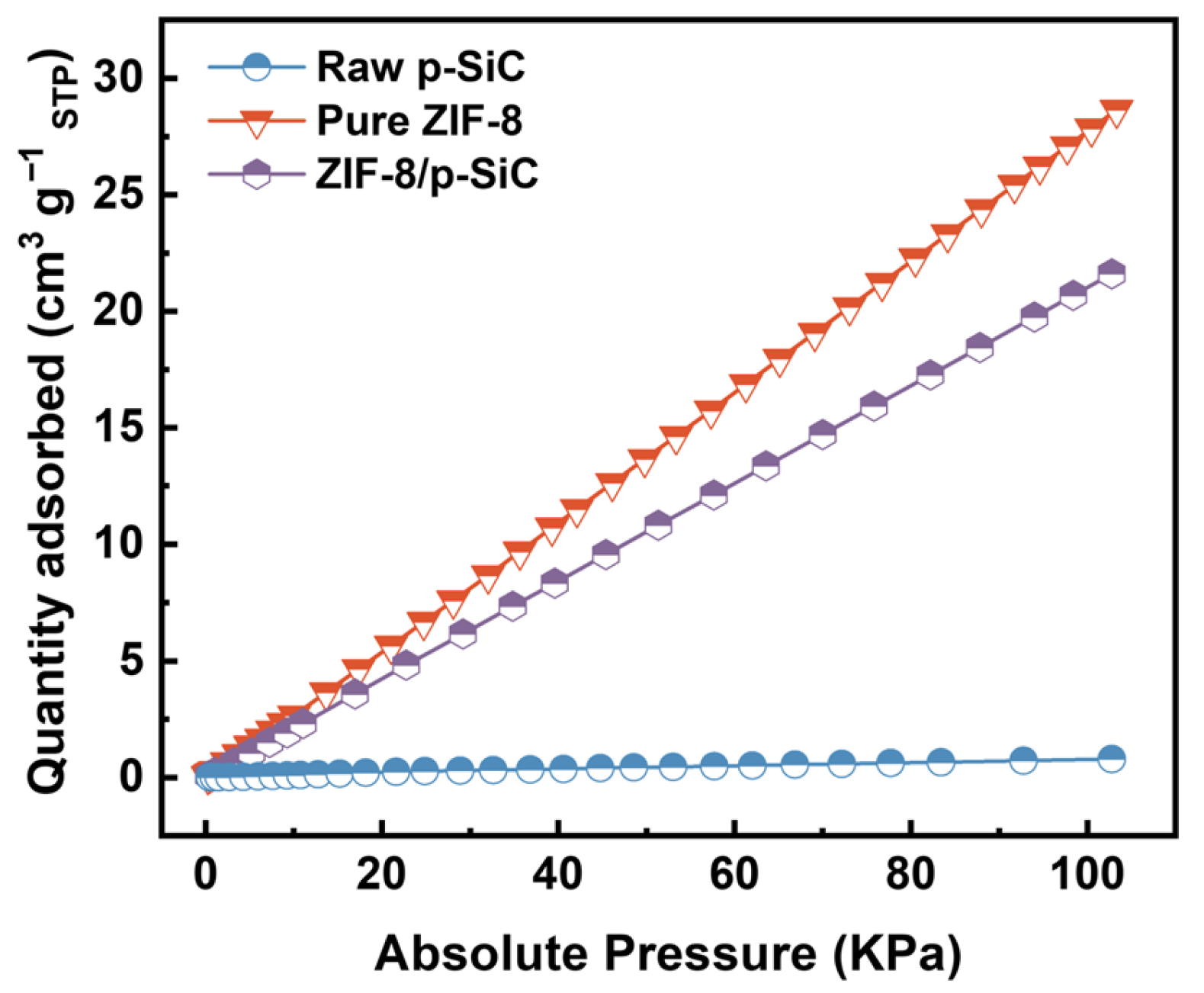

| Samples | SBET (m2 g−1) | Vtotal (cm3 g−1) | Dp (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw p-SiC | 0.1 | 0.012 a | 6.15 a |

| Pure ZIF-8 | 1588 | 0.938 b | - |

| ZIF-8/p-SiC | 18.3 | 0.021 a | 3.28 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, L.; Liao, G.; Lin, T.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Xiao, L. In Situ Growth of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Within Porous Silicon Carbide (p-SiC) for Constructing Hierarchical Porous Composites. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020117

Zhou L, Liao G, Lin T, Huang W, Zhang J, Fan R, Li Y, Zhang X, Cheng Z, Xiao L. In Situ Growth of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Within Porous Silicon Carbide (p-SiC) for Constructing Hierarchical Porous Composites. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020117

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Long, Guangzhi Liao, Tingting Lin, Wensong Huang, Jiawei Zhang, Ruiqi Fan, Yanghui Li, Xiaolin Zhang, Ziyun Cheng, and Lizhi Xiao. 2026. "In Situ Growth of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Within Porous Silicon Carbide (p-SiC) for Constructing Hierarchical Porous Composites" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020117

APA StyleZhou, L., Liao, G., Lin, T., Huang, W., Zhang, J., Fan, R., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Cheng, Z., & Xiao, L. (2026). In Situ Growth of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Within Porous Silicon Carbide (p-SiC) for Constructing Hierarchical Porous Composites. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020117