Tunable Optical Bistability in Asymmetric Dielectric Sandwich with Graphene

Abstract

1. Introduction

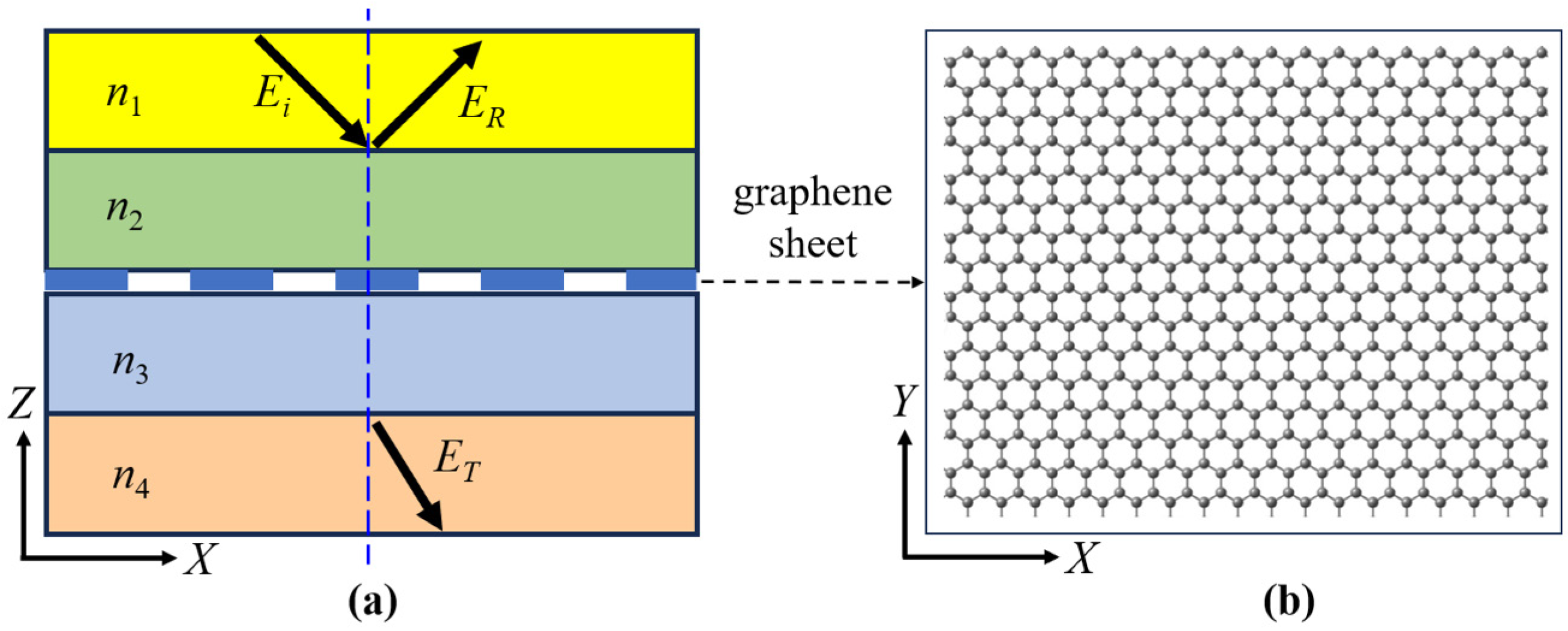

2. Theoretical Models and Methods

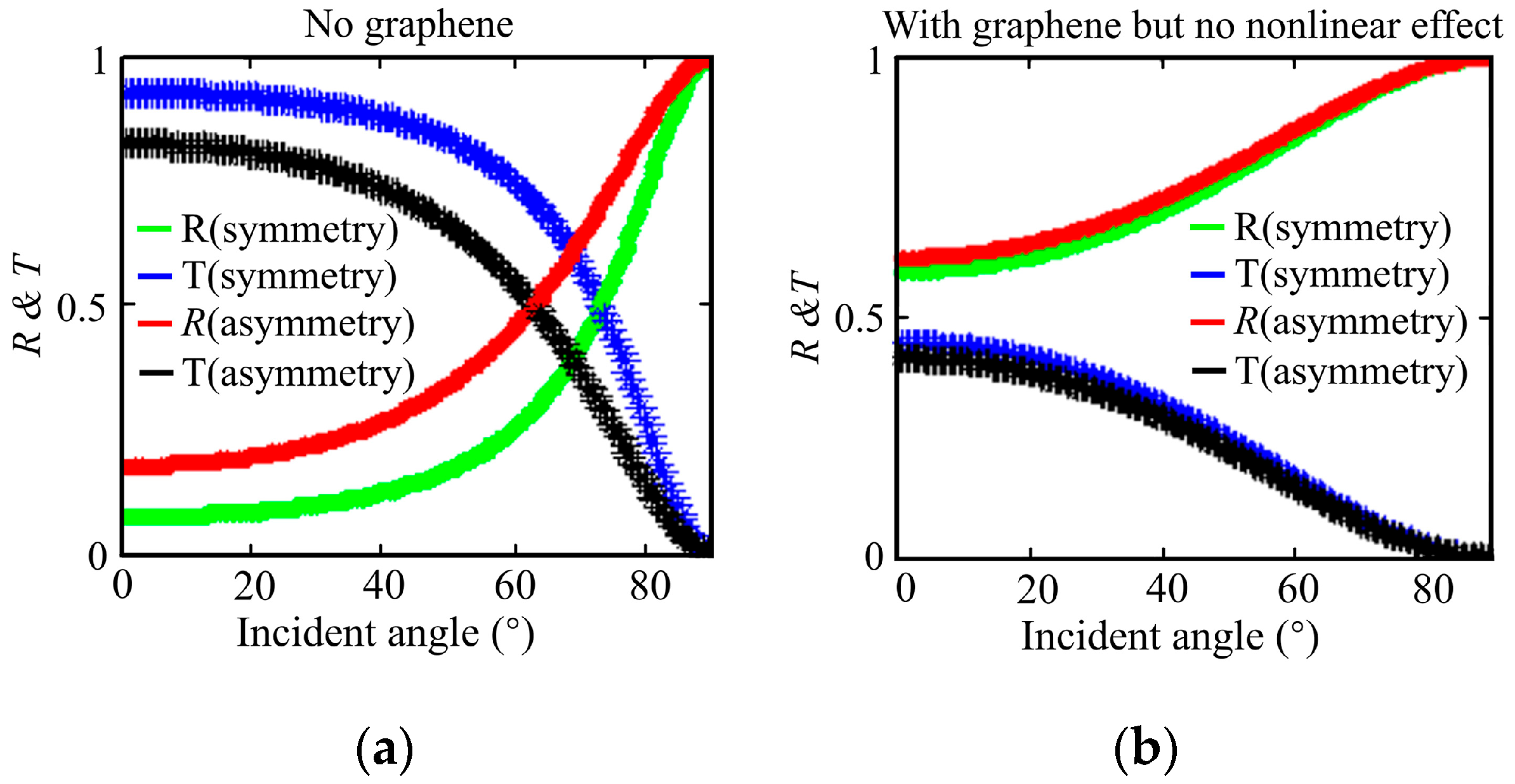

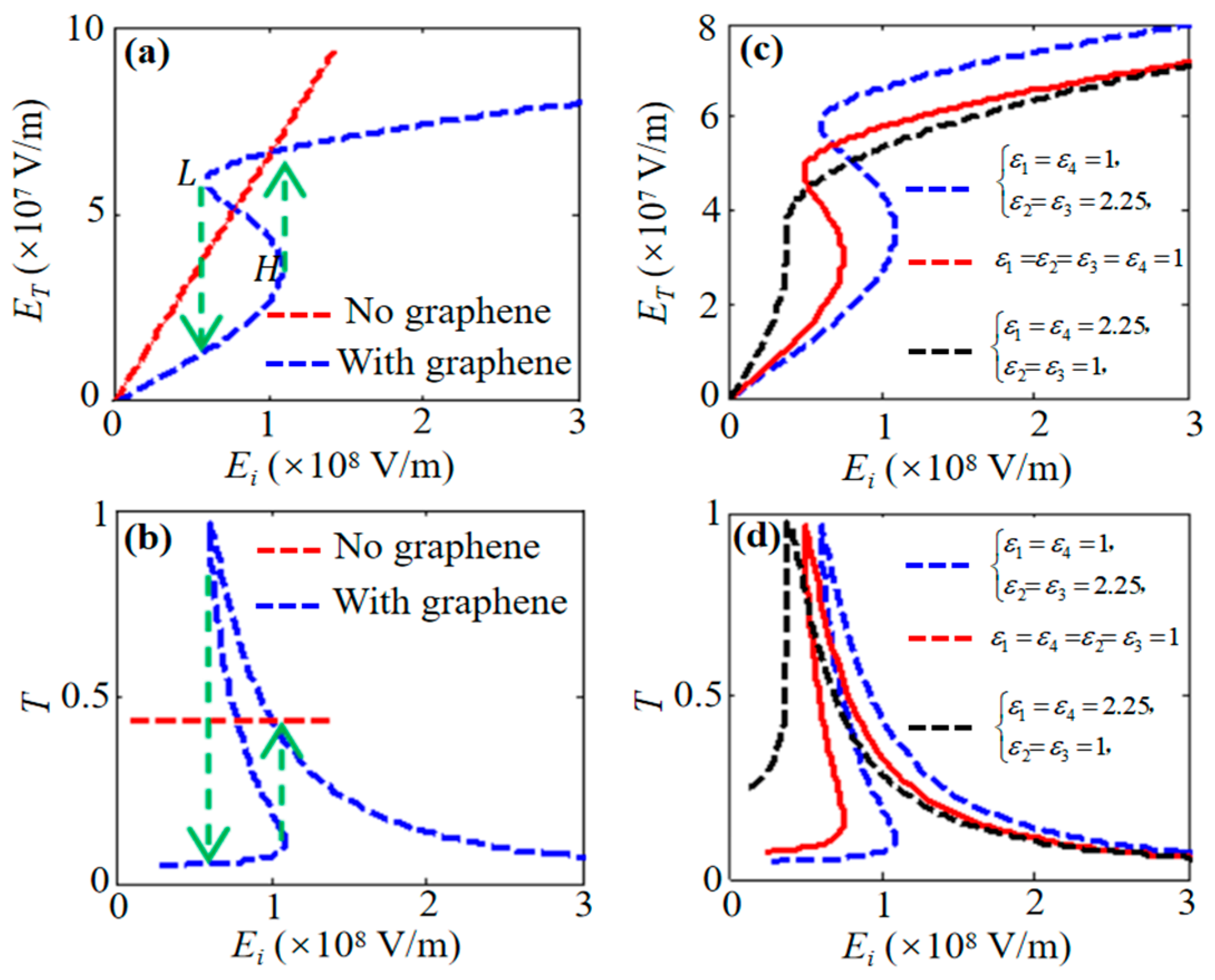

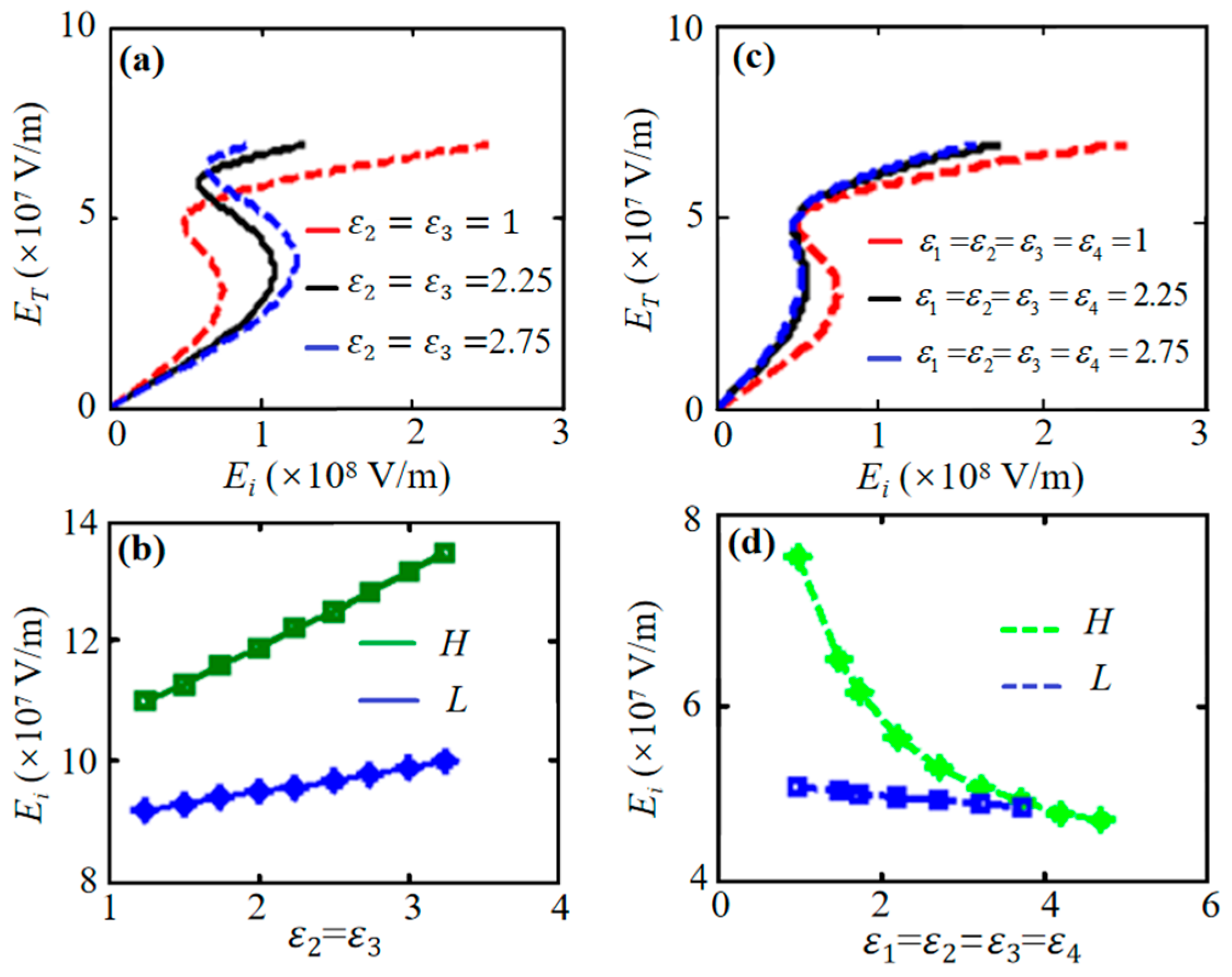

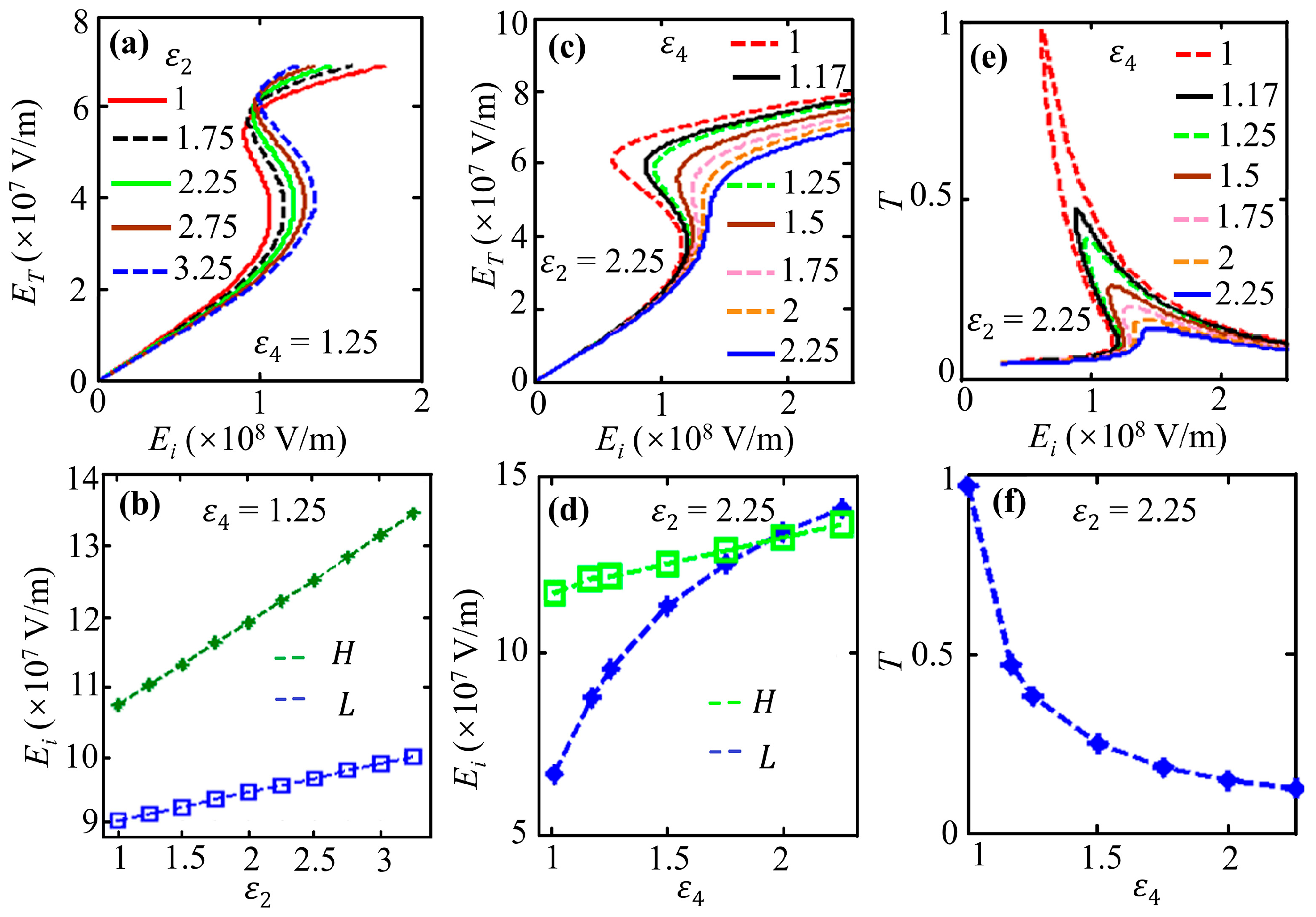

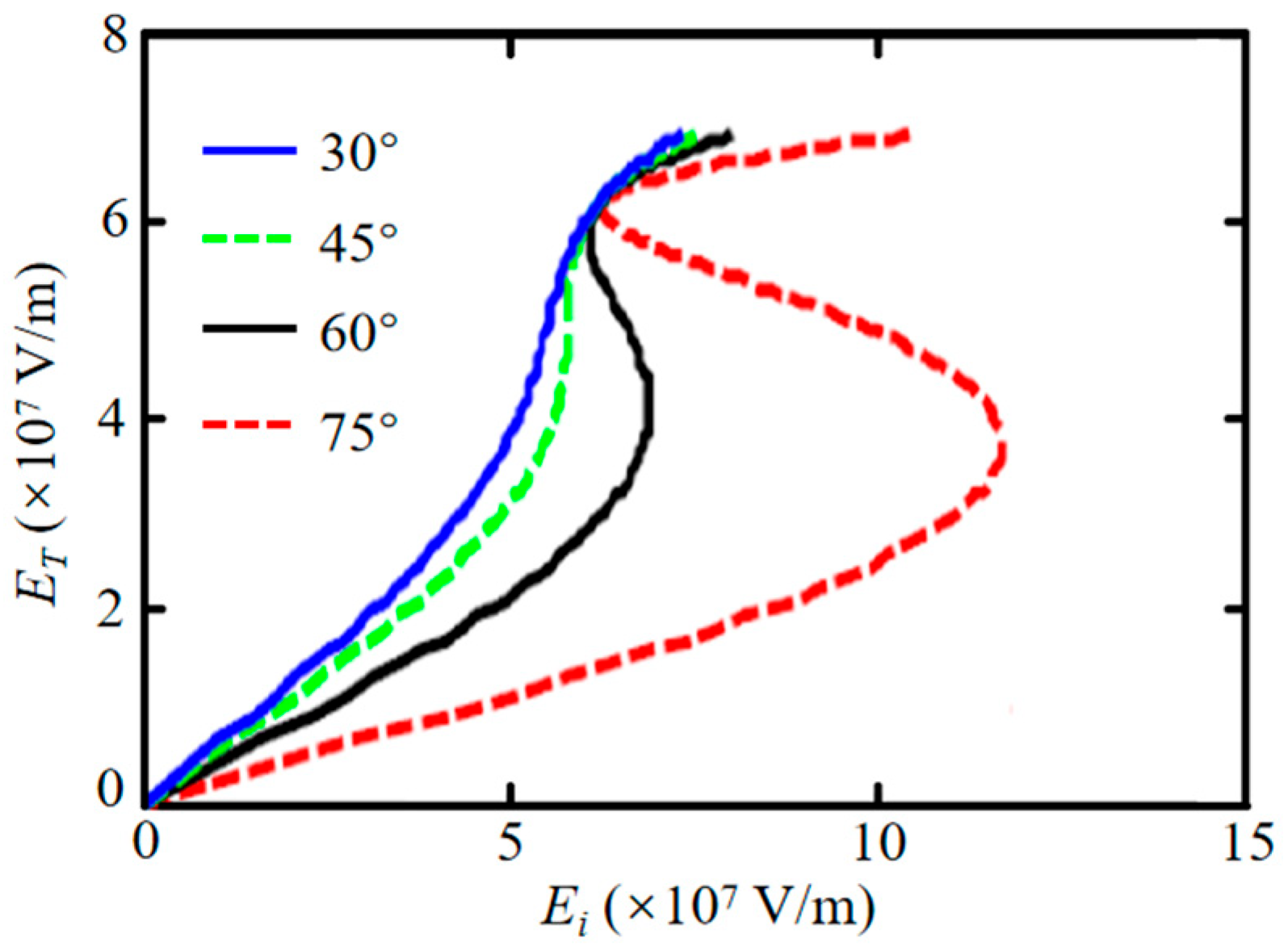

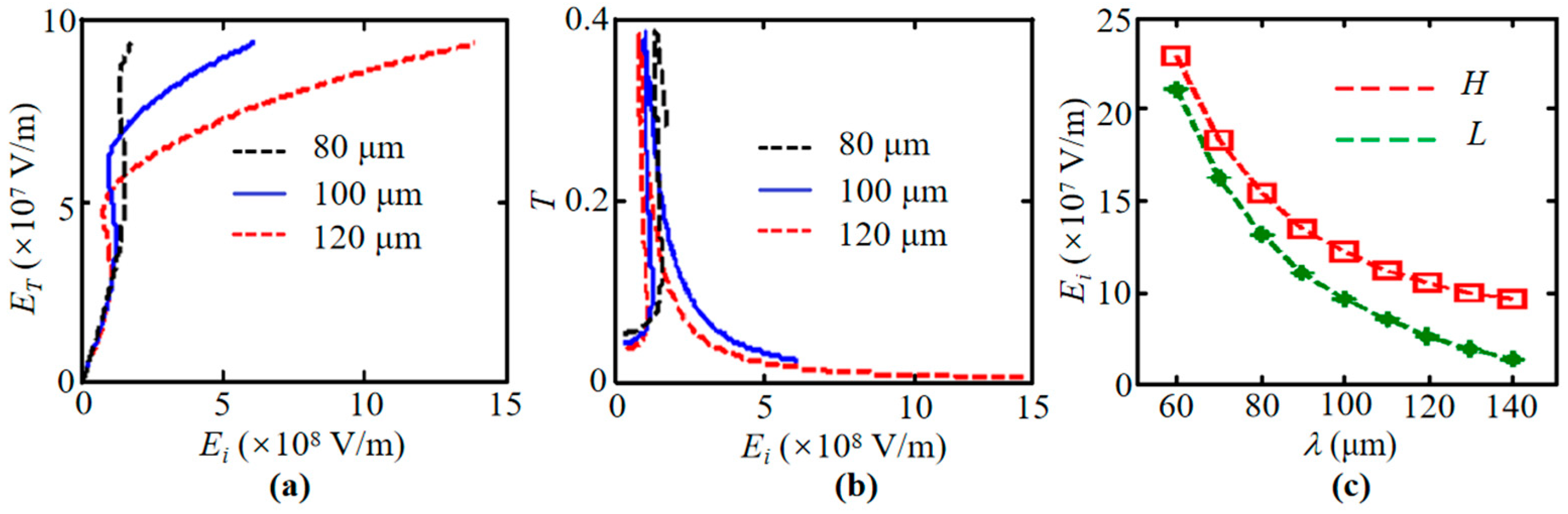

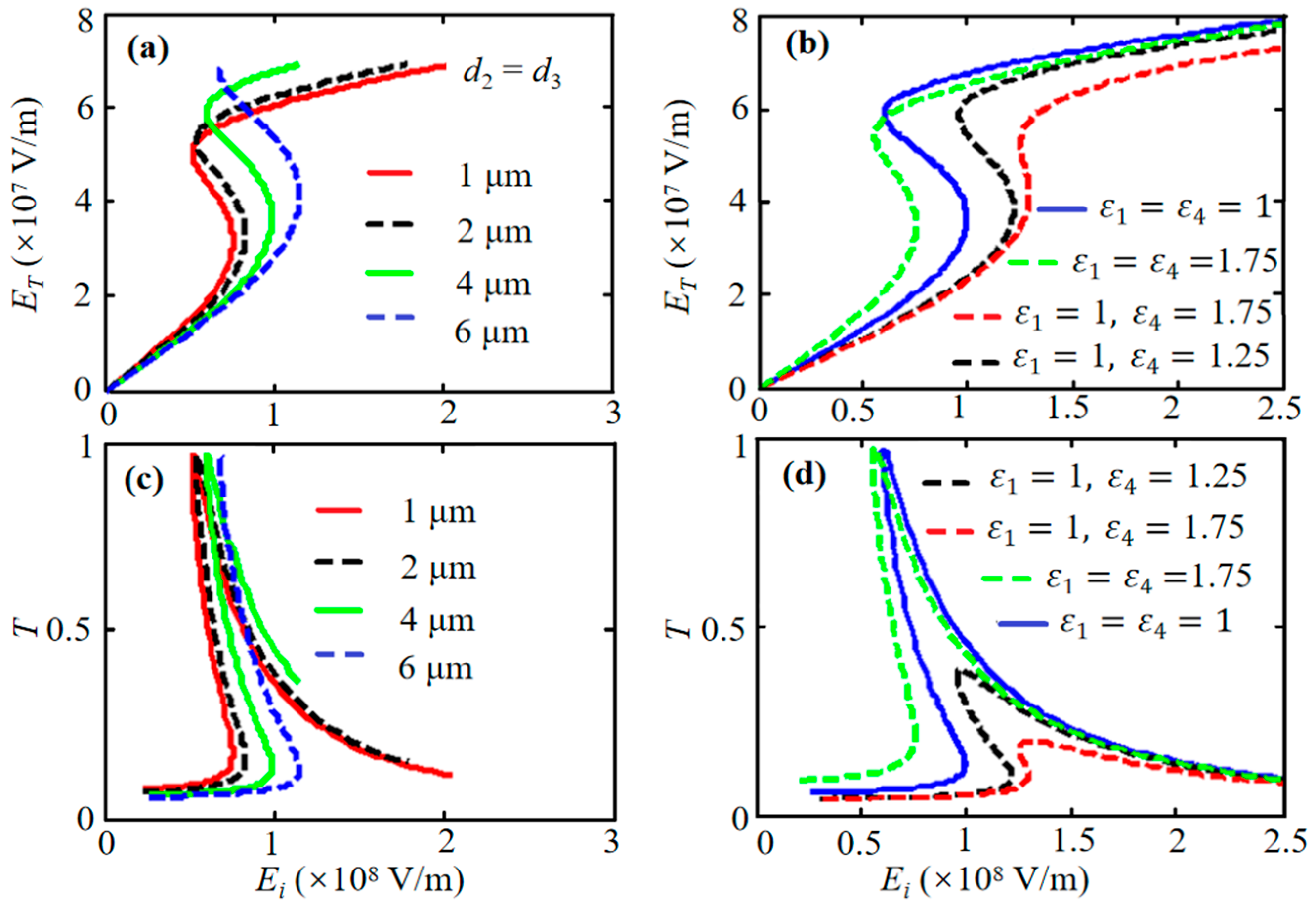

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gibbs, H.M. Optical Bistability: Controlling Light with Light; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, E.; Smith, S.D. Optical bistability and related devices. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1982, 45, 815–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.Y.; Li, G.X.; Tam, H.L.; Cheah, K.W.; Zhu, S.N. Optical bistability and multistability in one-dimensional periodic metal-dielectric photonic crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 211109. [Google Scholar]

- Min, C.; Wang, P.; Chen, C.; Deng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Ming, H.; Ning, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, G. All optical switching in subwavelength metallic grating structure containing nonlinear optical materials. Opt. Lett. 2008, 33, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, G.P. Optical bistability in metal gap waveguide nanocavities. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 8421–8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Y.; Alu, A. Optical nanoantenna arrays loaded with nonlinear materials. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 235405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Xia, Y. Analytical model for optical bistability in nonlinear metal nano-antennae involving Kerr materials. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 13337–13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.Y.; Farhat, M.; Alu, A. Bistable and self-tunable negative-index metamaterial at optical frequencies. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 105503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hendry, E.; Hale, P.J.; Moger, J.; Savchenko, A.K.; Mikhailov, S.A. Coherent nonlinear optical response of graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 097401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Virally, S.; Bao, Q.; Ping, L.K.; Massar, S.; Godbout, N.; Kockaert, P. Z-scan measurement of the nonlinear refractive index of graphene. Opt. Lett. 2012, 37, 1856–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, X.; Ulin-Avila, E.; Geng, B.; Zentgraf, T.; Ju, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. A graphene-based broadband optical modulator. Nature 2011, 474, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, F.; Sun, Z.; Hasan, T.; Ferrari, A.C. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat. Photonics 2010, 4, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assanto, G.; Wang, Z.; Hagan, D.J.; VanStryland, E.W. All-optical modulation via nonlinear cascading in type II second-harmonic generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1995, 67, 2120–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurenko, D.A.; Kerst, R.; Dijkhuis, J.I.; Akimov, A.V.; Golubev, V.G.; Kurdyukov, D.A.; Pevtsov, A.B.; Sel’kin, A.V. Ultrafast optical switching in three-dimensional photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 213903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nihei, H.; Okamoto, A. Photonic crystal systems for high-speed optical memory device on an atomic scale. Proc. SPIE 2001, 4416, 470–473. [Google Scholar]

- Simsek, E. Improving tuning range and sensitivity of localized SPR sensors with graphene. Photon. Technol. Lett. 2013, 25, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, B.; Jakovljević, M.M.; Isić, G.; Gajić, R. Tunable metamaterials based on split ring resonators and doped graphene. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 011102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Geng, B.; Horng, J.; Girit, C.; Martin, M.; Hao, Z.; Bechtel, H.A.; Liang, X.; Zettl, A.; Shen, Y.R.; et al. Graphene plasmonics for tunable terahertz metamaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andryieuski, A.; Lavrinenko, A.V. Graphene metamaterials based tunable terahertz absorber: Effective surface conductivity approach. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 9144–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.C.; Wei, Z.Y.; Li, H.Q.; Chen, H.; Soukoulis, C.M. Photonic band gap of a graphene-embedded quarter-wave stack. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 241403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.C.; Zhang, F.L.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, Z.Y.; Li, H.Q. Tunable terahertz coherent perfect absorption in a monolayer graphene. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 6269–6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaipa, C.S.R.; Yakovlev, A.B.; Hanson, G.W.; Padooru, Y.R.; Medina, F.; Mesa, F. Enhanced transmission with a graphene-dielectric microstructure at low-terahertz frequencies. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 245407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Yan, Y.; Shen, Z.; Loh, K.P.; Tang, D. Atomic-layer graphene as a saturable absorber for ultrafast pulsed lasers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 3077–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.K.; Chen, Z.L.; Clark, J.; Goh, R.G.S.; Ng, W.H.; Tan, H.W.; Friend, R.H.; Ho, P.K.H.; Chua, L.L. Giant broadband nonlinear optical absorption response in dispersed graphene single sheets. Nat. Photonics 2011, 5, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, S.A.; Ziegler, K. Nonlinear electromagnetic response of graphene: Frequency multiplication and the self-consistent-field effects. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 384204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Chen, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Q.; Loh, K.P.; Venkatesan, T. Graphene nanobubbles: A new optical nonlinear material. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015, 3, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, N.M.R.; Bludov, Y.V.; Santos, J.E.; Jauho, A.P.; Vasilevskiy, M.I. Optical bistability of graphene in the terahertz range. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 125425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Dai, X.; Guo, J.; Wen, S.; Tang, D. Tunable optical bistability at the graphene-covered nonlinear interface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 051108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Kowerdziej, R.; Pianelli, A.; Parka, J. Graphene-based tunable hyperbolic microcavity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, S.; Fabritius, T. Frequency-multiplexed tunable logic device based on terahertz graphene-integrated metamaterial composed of two circular ring resonator array. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, H.; Zhou, G.; Xu, S.; Liu, F.; Zhao, M.; Duan, S.; Zhao, D. Low-temperature optical bistability and multistability in superconducting photonic multilayers with graphene. Results Phys. 2023, 52, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, A.G.; Ghasemi, Z. Optical bistability in Anderson localized states of a random plasmonic structure based on graphene layers. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; He, M. Optical bistability modulation based on graphene sandwich structure with topological interface modes. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 40490–40497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Symbol | Value/Range |

|---|---|---|

| Dielectric permittivity | ε1, ε2, ε3, ε4 | 1.0–3.0 |

| Layer thicknesses | d1, d2, d3, d4 | 2–10 μm |

| Graphene Fermi energy | EF | 0.8 eV |

| Temperature | T | 300 K |

| Relaxation time | τ | ∞, (lossless) |

| Incident wavelength | λ | 80–120 μm |

| Incident angle | θ | 0–90° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, Q.; Liang, W.; Zhou, R.; Yang, S.; Li, S. Tunable Optical Bistability in Asymmetric Dielectric Sandwich with Graphene. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020116

Lin Q, Liang W, Zhou R, Yang S, Li S. Tunable Optical Bistability in Asymmetric Dielectric Sandwich with Graphene. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(2):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Qiawu, Wenyao Liang, Renlong Zhou, Sa Yang, and Shuang Li. 2026. "Tunable Optical Bistability in Asymmetric Dielectric Sandwich with Graphene" Nanomaterials 16, no. 2: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020116

APA StyleLin, Q., Liang, W., Zhou, R., Yang, S., & Li, S. (2026). Tunable Optical Bistability in Asymmetric Dielectric Sandwich with Graphene. Nanomaterials, 16(2), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16020116