Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nano-Aluminum: A Review on Oxidation, Structure Regulation, and Energetic Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Structural Characteristics and Oxidation Behavior of nAl

2.1. Core–Shell Structure and Its Impact on Reactions of nAl

2.1.1. Shell Growth Kinetics and Atomic Diffusion Mechanism of nAl

2.1.2. Reactivity Regulation Bottleneck and Optimal Size Range of nAl

2.1.3. Storage Stability and Surface Adsorption Mechanism of nAl

2.1.4. Application Verification of nAl’s Core–Shell Structure in Thermite Reactions

2.2. Experimental and Simulative Understanding of nAl’s Oxidation Mechanism

2.2.1. Diffusion-Oxidation Mechanism of nAl: Experimental Observation and Simulative Refinement

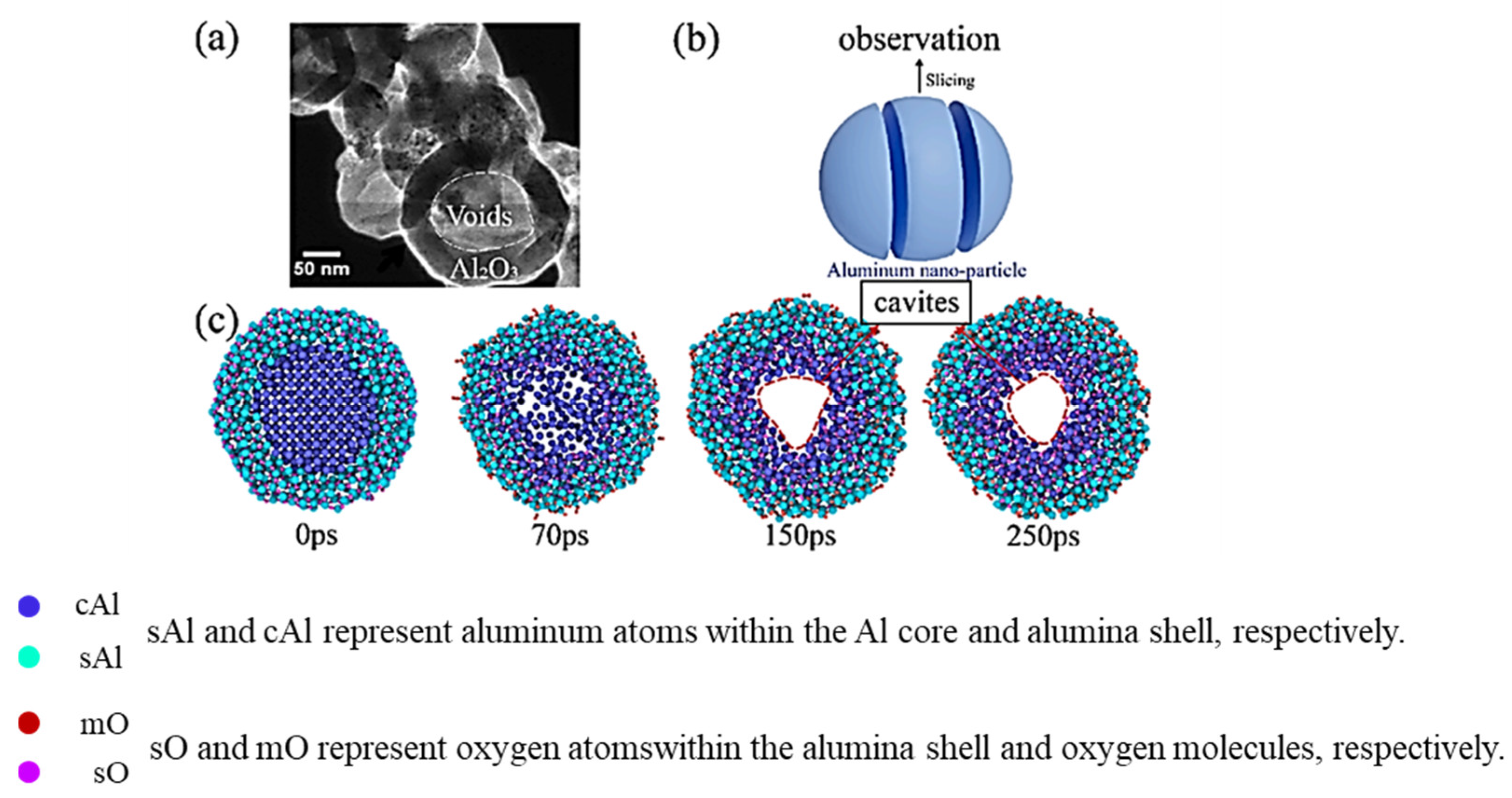

2.2.2. Melting-Dispersion Mechanism of nAl: Mechanism Breakthrough and Quantitative Support Under Extreme Conditions

2.2.3. Ion Diffusion Mechanism of nAl: Electric Field Effect and Simulation-Experiment Synergistic Verification

2.2.4. Expansion of Related Simulation Studies and Their Reference Significance

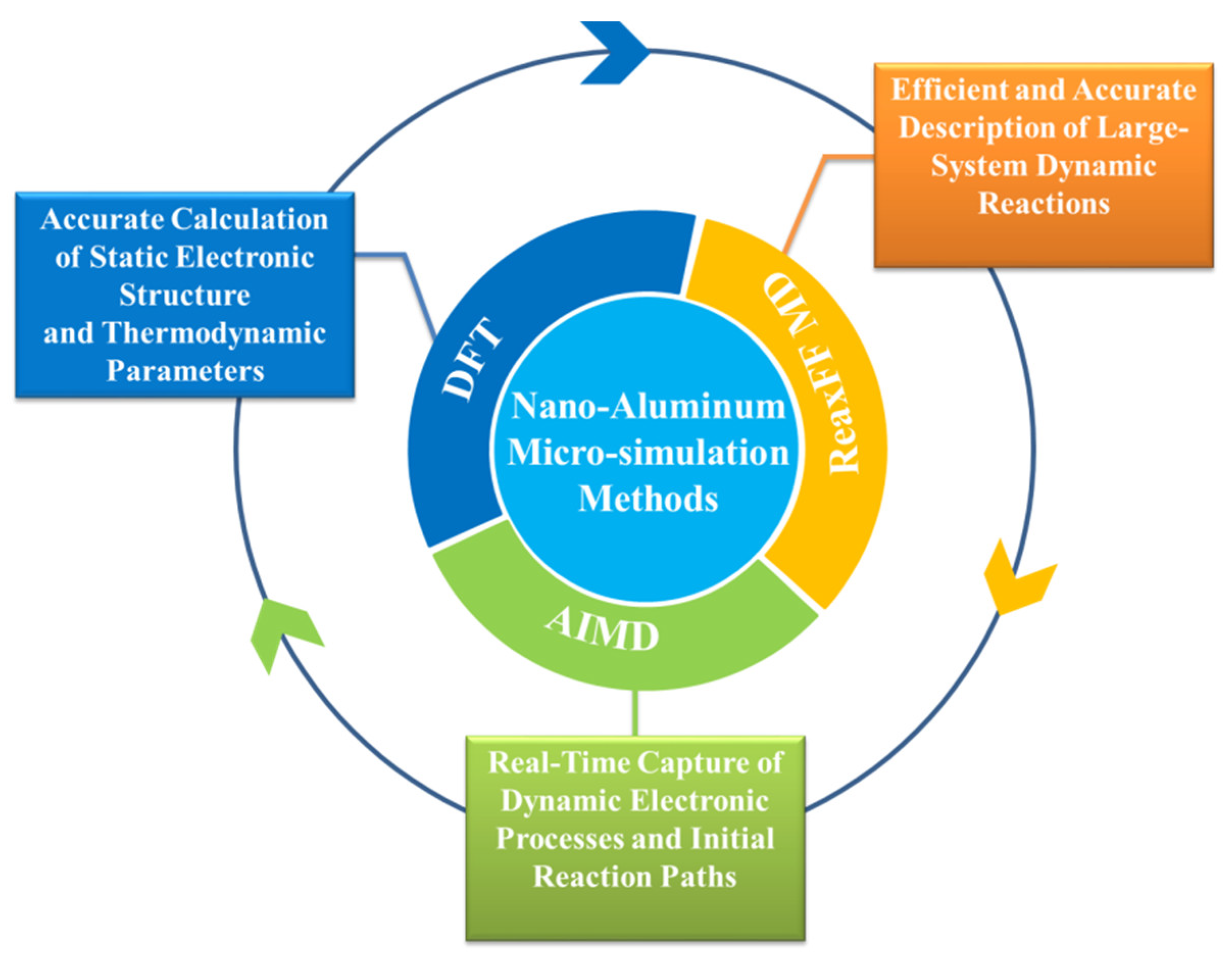

3. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Methods for nAl

3.1. Core Simulation Methods and Technical Characteristics of Molecular Dynamics for nAl

3.1.1. DFT Simulation: Accurate Calculation of Static Electronic Structure and Thermodynamic Parameters

3.1.2. AIMD Simulation: Real-Time Capture of Dynamic Electronic Processes and Initial Reaction Paths

3.1.3. ReaxFF MD Simulation: Efficient and Accurate Description of Large-System Dynamic Reactions of nAl

3.2. Force Field Development and Latest Progress in Molecular Dynamics Simulation of NA

3.2.1. Multi-Component Force Fields: Cross-System Adaptability and Machine Learning Empowerment

3.2.2. Extreme Condition-Adapted Force Fields: Breakthroughs in High-Temperature, High-Pressure, and Impact Load Scenarios

3.2.3. Special Research: Gas–Solid Interaction Potential Function and Energy Transfer Kinetics Support

4. Core Value of MD Simulation in Energetic Applications of nAl

4.1. Surface Modification and Stability Regulation

4.1.1. Organic Coating Mechanism: From Agglomeration Inhibition to Sintering Barrier

4.1.2. Inorganic Coating Optimization: Crystal Form Regulation and Long-Term Stability

4.1.3. Energetic Coating Design: Balance Between Stability and Energy Performance

4.1.4. Special Research: Interface Regulation and In-Depth Verification of Coating Mechanism

4.2. Atomic-Level Analysis of Combustion Mechanism

4.2.1. Resolution of Ignition Mechanism Controversy: Accurate Revelation of Dynamic Oxide Shell Rupture Process

4.2.2. Atomic Diffusion Kinetics: Analysis of Reaction Driving Force and Key Influencing Factors

4.2.3. Product Evolution Law: Tracking of Species Formation and Reaction Phase Transition

4.2.4. Special Research: Multi-Dimensional Mechanism Deepening and Application Scenario Verification

4.3. Interface Design of Energetic Composite Systems

4.3.1. Interface Stability Regulation: Crystal Plane Selection and Interaction Mechanism Analysis

4.3.2. Interface Reaction Kinetics Regulation: Key Factors and Optimization Strategies

4.3.3. Special Research: Multi-Scenario Interface Mechanism Deepening and Design Strategies

5. Research Challenges and Future Outlook

5.1. Current Core Challenges

5.1.1. Lack of Simulation Under Multi-Load Coupling Conditions

5.1.2. Lack of Explicit Mesoscale Description

5.1.3. Difficulties in Experiment-Simulation Quantitative Verification

5.2. Future Development Directions

5.2.1. Development of Multi-Field Coupling Simulation Technology

5.2.2. Breakthroughs in Intelligent Force Fields and Efficient Computing

5.2.3. Construction of Experiment-Simulation Closed-Loop System

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, P.A.; Liu, J.P.; Wang, M.J. Ignition and combustion of nano-sized aluminum particles: A reactive molecular dynamics study. Combust. Flame 2019, 201, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, M.G.; Elbeih, A.; Elshenawy, T. Review of nanothermites: A pathway to enhanced energetic materials. Cent. Eur. J. Energetic Mater. 2021, 18, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.D.; Cheng, X.L.; Zhang, C.Y.; Lu, Z.P. Responses of core-shell Al/Al2O3 nanoparticles to heating: ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 9191–9197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Wang, Y.J.; Gan, Q.; Feng, C.G. Research Pogres in M croscopic Simuation of Nanothemite. Chin. J. Explos. Propellants 2022, 45, 597–611. [Google Scholar]

- Bazyn, T.; Glumac, N.; Krier, H.; Ward, T.S.; Schoenitz, M.; Dreizin, E.L. Reflected shock ignition and combustion of aluminum and nanocomposite thermite powders. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2007, 179, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Application of nano-aluminum in solid propellants: A review. J. Propuls. Technol. 2023, 44, 1120–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z. Micro-ignition performance of nAl-based composite energetic materials for MEMS. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 358, 114123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Xue, J.; Zhang, L. Enhanced detonation performance of high-explosive formulations with modified nano-aluminum. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2023, 48, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S. On-site welding of steel structures using nAl-based thermite composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 367, 131245. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.; Gao, H.; Wang, G.X.; Gong, X.D. Interfacestmcture and stability of Al/Fe2O3 nano thermite: A periodic DFT study. Chin. J. Energet. Mater. 2022, 30, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Shimojo, F.; Nakano, A.; Kalla, R.K.; Vashishta, P. Enhanced reactivity of nanoenergetic materials: A first-principles molecular dynamics study based on divide-and-conquer density functional theory. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 043114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, H.; Gao, J.X.; Cheng, X.L. Molecular dyamics investigation of themite reaction behavior of nanostructured Al/SiO2 system. Acta Phys. Sin. 2014, 63, 86401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Lee, D.; Park, K.; Zachariah, M.R. Importance of phase change of aluminum in oxidation of aluminum nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 14793–14795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlott, D.D.; Parrish, C.F.; Anderson, M.U. Laser-induced explosive boiling of aluminum nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Aumann, J.; Dreizin, E.L.; Glumac, N.G. Ignition of aluminum nanoparticles by a CO2 laser. Combust. Flame 2006, 144, 767–776. [Google Scholar]

- Maini, S.; Wang, A.Q.; Wen, J.Z. Characteristics of Gasless Combustion of Core−Shell Al@NiO Microparticles with Boosted Exothermic Performance. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 36434−36444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Park, K.; Zhou, L.; Zachariah, M.R. Understanding the mechanism of aluminium nanoparticle oxidation. Combust. Theory Model. 2006, 10, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.Z.; Shi, B.L.; Liao, L.J.; Luo, K.H.; Wang, N.F.; Huang, C.G. Ignition and oxidation of core-shell Al/Al2O3 nanoparticles in an oxygen atmosphere: Insights from molecular dynamics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 29620–29627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitas, V.I.; Asay, B.W.; Son, S.F.; Pantoya, M. Mechanochemical mechanism for fast reaction of metastable intermolecular composites based on dispersion of liquid metal. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 083524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Niu, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, C. Crack mechanism of Al@Al2O3 nanoparticles in hot energetic materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henz, B.J.; Hawa, T.; Zachariah, M.R. On the role of built-in electric fields on the ignition of oxide coated nanoaluminum: Ion mobility versus Fickian diffusion. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 24901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhdanov, V.P.; Kasemo, B. Cabrera-Mott kinetics of oxidation of nm-sized metal particles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 452, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, J.; He, B.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, S. Study on the evolutionary mechanism of the cavity inside aluminum nanoparticles while reacting with oxygen. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 241, 113040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsin, M.; Fachri, B.A.; Nurdiansyah, H. Effect of particle size on ignition and oxidation of single aluminum: Molecular dynamics study. EUREKA: Phy. Eng. 2023, 3, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.T.; He, M.; Cheng, G.X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z. Effect of ionization on the oxidation kinetics of aluminum nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 16, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.J.; Li, A.Q.; Zeng, X.Z.; Chen, X.H.; Yang, W.J.; Zhang, Y.H.; Li, X.M. Highly stable nano aluminum coated by self-assembled metal-phenolicnetwork and enhancing energetic performance of nanothermite. J. Alloy. Comp. 2025, 1011, 178482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiruvengadathan, R. Aluminum-Based Nano-energetic Materials: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. In Nano-Energetic Materials. Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Bhattacharya, S., Agarwal, A., Rajagopalan, T., Patel, V., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C. Investigation of Oxidation Mechanisms for Aluminum Micro-and Nanoparticles of Various Geometries VIA Nanosecond Laser Irradiation. Master’s Thesis, University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, Indiana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro, D.; Goudeli, E. Oxidation Rate Crystallinity Dynamics of Silver Nanoparticles at High Temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2023, 127, 13389–13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.Z.; Bandaru, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Lau, W.M.; Wang, Z.L. Al atom on MoO3(010) surface: Adsorption and penetration using density functional theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 7359–7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.Y.; Zhao, J.J. Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Energetic Materials. Chin. J. High Press. Phys. 2015, 29, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.; Xiong, G.; Zhu, W. Ab initio molecular dynamics studies on the ignition and combustion mechanisms, twice exothermic characteristics, and mass transport properties of Al/NiO nanothermite. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 11364–11376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. In Situ TEM Observation of Al/SiO2 Nanothermite Reaction. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 5678–5685. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.X.; Zhao, S.J. Applicability of ReaxFF Potential in Aluminum. Chin. J. Energetic Mater. 2012, 20, 571–574. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.W.; Zhu, W.B.; Wang, T.; Yilmaz, D.E.; Duin, A.C.T. C/H/O/F/Al ReaxFF Force Field Development and Application to Study the Condensed-Phase Poly(vinylidene fluoride) and Reaction Mechanisms with Aluminum. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2022, 126, 11058–11074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, S.; Marques, M.A.; Nunes, M.I. Density functional tight-binding for beginners: A short guide to the code DFTB+. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. DFTB+ study on the initial oxidation of aluminum nanoparticles: Charge transfer and bond formation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 219, 111892. [Google Scholar]

- Foiles, S.M.; Baskes, M.I.; Daw, M.S. Embedded-atom-method functions for the fcc metals Cu, Ag, Au, Ni, Pd, Pt, and their alloys. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33, 7983–7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Development of ReaxFF parameters for Al-Ni-O system. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 191, 110289. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.S.; Nebgen, B.T.; Zuo, Y. Machine learning for reactive force fields. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1092–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; van Duin, A.C. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Oxidation of Aluminum Nanoparticles using the ReaxFF Reactive Force Field. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 17876–17886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Mei, Z.; Zhang, T.C.; Zhou, S.Q.; Ju, X.H. Overview of ReaxFF Force Field Method and It’s Application in Energetic Materials. Chin. J. Explos. Propellants 2023, 46, 465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Thoudam, J.; Bayad, I.J.; Sundaram, D.S. Dynamics of Energy Transfer between Nanoscale Aluminum/Aluminum Oxide Particles and Nitrogen Gas in the Noncontinuum Regime. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2024, 128, 3497–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P.; Wang, M.J.; Liu, P.G.; Sun, R.C.; Yang, Y.X.; Zou, G.W. Molecular dynamics study of sintering of Al nanoparticles with/without organic coatings. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 190, 110265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yan, Q. Anti-sintering behavior and combustion process of aluminum nanoparticles coated with PTFE: A molecular dynamics study. Def. Technol. 2023, 19, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, L. DFT Study on SiO2-Coated Al/CuO Nanothermites for Enhanced Stability. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 489, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Li, H.; Chen, G. Synthesis and characterization of Al/TiO2 nanothermites. J. Nanomater. 2024, 2024, 7854932. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Surface modification of aluminum nanoparticles with fluorocarbon compounds. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 499, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Ethanol-assisted surface modification of aluminum nanoparticles for enhanced combustion performance. Fuel 2025, 386, 122891. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S.H.; Zhu, W.H. Unraveling the adhesive properties, thermal stability, and initial diffusion mechanisms of Al/NiO nanothermites with various dominant surfaces: A first-principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 603, 154399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.H.; Zhang, L.L.; Mao, R.J.; Qin, C.W.; Pang, W.Q. Application Process of Coating Agent and the Coating Effect Evaluation Based on Molecular Dynamics. Langmuir 2023, 39, 3411–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B.; Ma, W.J.; Chen, Z.H.; Wang, L. Molecular dynamic simulations of carbon coated aluminum nanoparticle with core–shell structure for oxidation resistance behaviors and mechanism. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 095116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.M.; Zhao, F.; Chen, X.X.; Chen, H.J.; Cheng, X.L. Thermite reaction of Al and α-Fe2O3 at the nanometer interface: Ab initio molecular dynamics study. Acta Phys. Sin. 2013, 247101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.L.; Yang, C.H.; Feng, S.H.; Zhu, W.H. Ab initio molecular dynamics studies on the transport mechanisms of oxygen atoms in the adiabatic reaction of Al/CuO nanothermite. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 745, 137278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Cheng, X.; Ma, B. Reaction characteristics and iron aluminides products analysis of planar interfacial Al/α-Fe2O3 nanolaminate. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2017, 127, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.Y.; Ma, B.; Tang, C.M.; Cheng, X.L. Molecular dynamic simulation of thermite reaction of Al nanosphere/Fe2O3 nanotube. Phys. Lett. Sect. A Gen. At. Solid State Phys. 2016, 380, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Piekiel, N.; Chowdhury, S.; Zachariah, M.R. Time-resolved mass spectrometry of the exothermic reaction between nanoaluminum and metal oxides: The role of oxygen release. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 14269–14275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Xu, J.; Xue, Z.; Yan, Q.L. Combustion performance modulation and agglomeration inhibition of HTPB propellants by fine Al/oxidizers integration. Fuel 2024, 367, 131587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.A.; Xu, J.Y. The oxygen vacancy defect induced by Ar plasma significantly reduces the initial reaction energy barrier of micron thermite and improves its combustion reaction efficiency. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 685, 161955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Gao, P.; Wang, G.X.; Gong, X.D. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations on the combustion mechanism of Al/Fe2O3 nanothermite at various temperatures. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 246, 113427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabraoui, H.; Esteve, A.; Schoenitz, M.; Dreizin, E.L.; Rossi, C. Atomic Scale Insights into the First Reaction Stages Prior to Al/CuO Nanothermite Ignition: Influence of Porosity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 29451–29461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.X.; Zachariah, M.R. Molecular Dynamics Study on the Capture of Aluminum Particles by Carbon Fibers during the Propagation of Aluminum-Based Energetics. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 8992–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Chu, Y.H.; Wang, F.; Yuan, S.; Tan, M.H.; Fu, H.; Jia, Y. Coulomb Effect of Intermediate Products of Core–Shell SiO2@Al Nanothermite. Molecules 2025, 30, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicham, J.; Mehdi, D.R.; Carole, R.; Alain, E. Density functional theory calculations of surface thermochemistry in Al/CuO thermite reaction. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8, 115401. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.L.; An, M.; Dai, M.N.; Li, S.T.; Chen, Y.Q.; Song, R.; Song, J.X.; Chen, L.M.; Zhong, X.T.; Tian, Q.W. Effect of Crystal Phase on the Thermal and Combustion Properties of MnO2/Al Nanothermites. JOM 2025, 77, 3748–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanthony, C.; Ducere, J.; Esteve, A.; Rossi, C.; Rouhani, M.D. Formation of Al/CuO bilayer films: Basic mechanisms through density functional theory calculations. Thin Solid Film. 2012, 520, 4768–4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.A.; Xu, J.Y.; Zhang, W.C.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, G.; Liu, Q.; Gu, B. The role of MnO2 crystal facets in aluminothermic reaction of MnO2/nAl composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.H.; Zhu, W.H. Effects of uniaxial stress and temperature on the interfacial tensile strength and stability of Al/NiO nanolaminates: A first-principles study. Fuel 2023, 352, 129147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N.; Li, J.; Wang, B.L.; Ma, H.; Han, Z.W. An approach to the induced reaction mechanism of the combustion of the nano-Al/PVDF composite particles. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2022, 429, 127912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Adams, J.B. Adhesive metal transfer at the Al(111)/α-Fe2O3(0001) interface: A study with ab initio molecular dynamics. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2008, 16, 085001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. MD-CFD coupling model for predicting combustion performance of nano-aluminum based propellants. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2022, 47, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Levitas, V.I.; Pantoya, M.L.; Dean, S. Melt dispersion mechanism for fast reaction of aluminum nano-and microscale particles: Flame propagation and SEM studies. Combust. Flame 2014, 161, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, N.N.; Bai, S.; Chang, J.; Ji, G.F. Shock response of condensed-phase RDX: Molecular dynamics simulations in conjunction with the MSST method. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 17312–17320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Ye, X.; Yao, H.B.; Wei, P.Y.; Yin, F.; Cong, J.W.; Tong, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, W.H. Simulation of femtosecond laser ablation and spallation of titanium film based on two-temperature model and molecular dynamics. J. Laser Appl. 2021, 33, 12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mei, Z.; Zhao, F.Q.; Xu, S.Y.; Ju, X.H. Atomic perspectives revealing the evolution behavior of aluminum nanoparticles in energetic materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 563, 150296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.P. Molecular Dynamics Study on Coating and Combustion of Aluminum Nanoparticles Based on ReaxFF Force Field. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Zhao, C.D.; Yu, Q.; Yang, F.; Chen, J. Revealing Al-O/Al-F reaction dynamic effects on the combustion of aluminum nanoparticles in oxygen/fluorine containing environments: A reactive molecular dynamics study meshing together experimental validation. Def. Technol. 2024, 34, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Oxidation Mechanism | Key Trigger Conditions | Dominant Particle Size Range | Typical Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion-oxidation | Heating rate ≤ 105 K/s, normal pressure | 30–100 nm | Slow ignition, long-term storage oxidation |

| Melting-dispersion | Heating rate ≥ 106 K/s, pressure ≥ 2.3 MPa | 10–50 nm | Explosion, pulse heating, high-energy ignition |

| Ion diffusion | Temperature 800–2000 K, intrinsic electric field in Al2O3 shell | 20–80 nm | Electrochemical reaction, medium-temperature rapid oxidation |

| Simulation/Experimental Conditions | Initial Ignition Temperature/K | Primary Exotherm Initiation Temperature/K | Secondary Exotherm Initiation Temperature/K |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 → 1500 K Heating Simulation (16O) | 522 | 729 | 909 |

| 10 → 1500 K Isothermal Simulation (18O) | 730 | 904 | 1142 |

| Experiment 1 (DSC) | – | 742 | 918 |

| Experiment 2 (TG-DTA) | – | 774 | 918 |

| Experiment 3 (Laser Ignition) | – | 733 | 839 |

| Experiment 4 (High-Pressure DSC) | – | 673 | 803 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ouyang, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Cheng, H.; Pang, W.; Qiu, J. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nano-Aluminum: A Review on Oxidation, Structure Regulation, and Energetic Applications. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010074

Ouyang D, Chen X, Zhang Q, Yu C, Cheng H, Pang W, Qiu J. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nano-Aluminum: A Review on Oxidation, Structure Regulation, and Energetic Applications. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleOuyang, Dihua, Xin Chen, Qiantao Zhang, Chunpei Yu, He Cheng, Weiqiang Pang, and Jieshan Qiu. 2026. "Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nano-Aluminum: A Review on Oxidation, Structure Regulation, and Energetic Applications" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010074

APA StyleOuyang, D., Chen, X., Zhang, Q., Yu, C., Cheng, H., Pang, W., & Qiu, J. (2026). Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nano-Aluminum: A Review on Oxidation, Structure Regulation, and Energetic Applications. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010074