Mechanical Enhancements of Electrospun Silica Microfibers with Boron Nitride Nanotubes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Material Properties

3.2. Mechanical Properties

| Matrix Material | Manufacturing Method | BNNT Concentration (wt.%) | Strength | Toughness | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexural Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Fracture Toughness (MPa·m1/2) | Toughness (kJ/m3) | ||||

| SiO2 | Electrospinning | 0 | - | 187.1 | - | 430.9 | This work |

| 0.5 | - | 223.3 | - | 486.0 | |||

| molding | 0 | 52.2 | - | 0.58 | - | [12] | |

| 5 | 120.5 | - | 1.21 | - | |||

| molding | 0 | 27.3 | - | 0.58 | - | [33] | |

| 5 | 44.2 | - | 0.68 | - | |||

| Additive manufacturing | 0 | 13.7 | - | - | - | [14] | |

| 0.1 | 21.2 | - | - | - | |||

| molding | 0 | 23.0 | - | 0.54 | - | [15] | |

| 0.5 | 68.3 | - | 1.44 | - | |||

| Additive manufacturing | 0 | 14.0 | - | 0.20 | - | [19] | |

| 0.4 | 33.6 | - | 0.50 | - | |||

| Al2O3 | Plasma spray coating | 0 | - | - | 2.05 | - | [13] |

| 5 | - | - | 3.10 | - | |||

| molding | 0 | 319 | - | 4.9 | - | [34] | |

| 2 | 532 | - | 6.1 | - | |||

| molding | 0 | 365.6 | - | 5.2 | - | [35] | |

| 1.5 | 580.9 | - | 6.1 | - | |||

| Additive manufacturing | 0 | 47.2 | - | 1.0 | - | [16] | |

| 0.6 | 80.6 | - | 1.8 | - | |||

| ZrO2 | molding | 0 | 895.5 | - | 7.94 | - | [36] |

| 1 | 1143.3 | - | 13.13 | - | |||

| Si3N4 | molding | 0 | 895 | - | 7.1 | - | [37] |

| 1.5 | 1150 | - | 8.2 | - | |||

| SiOC | molding | 0 | 55.5 | - | 0.9 | - | [17] |

| 1.0 | 137.4 | - | 3.0 | - | |||

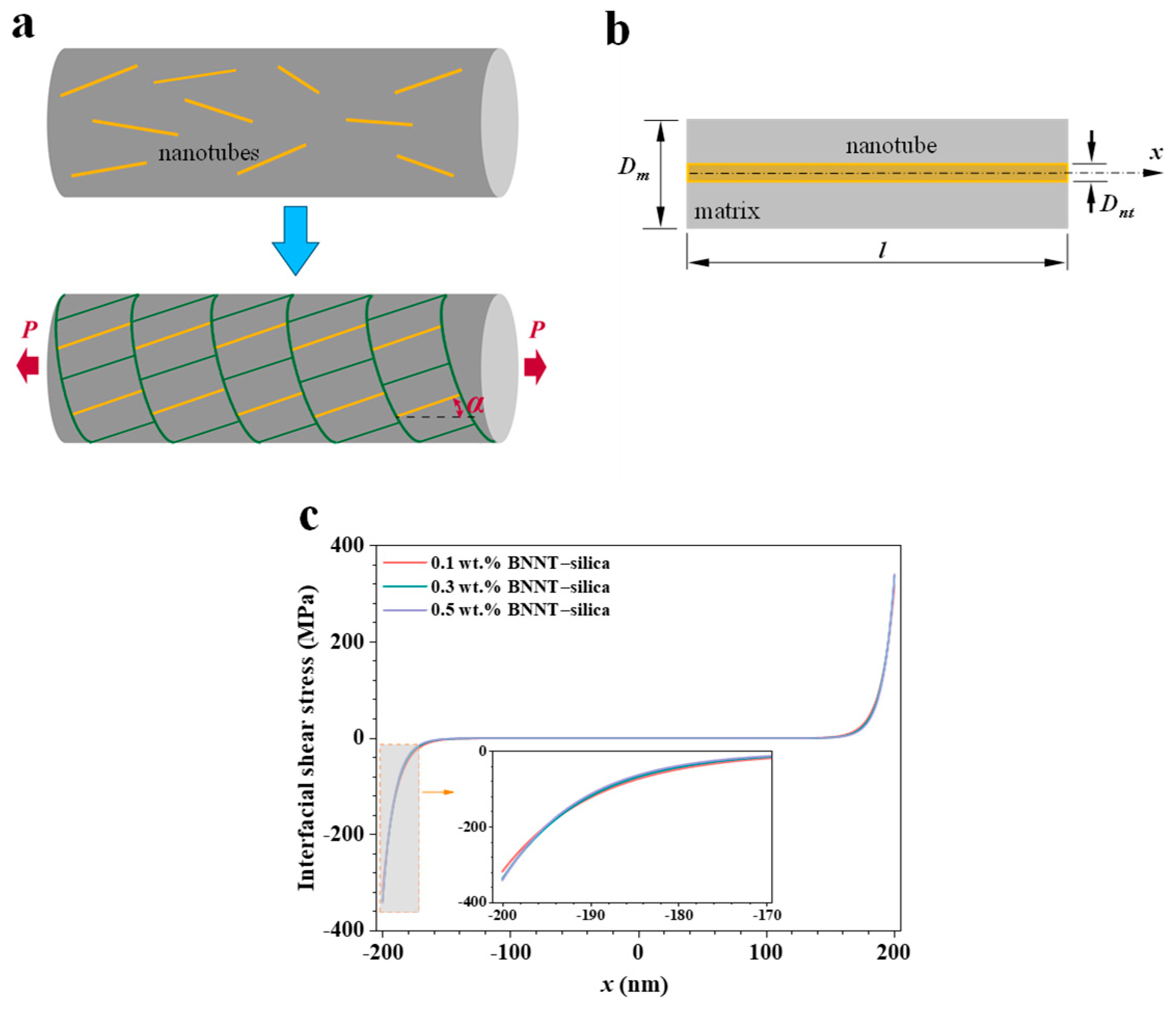

3.3. Nanotube Alignment Inside the Matrix

3.4. In Situ Raman Micromechanical Measurements

3.5. Interfacial Load Transfer Characteristics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afolabi, O.A.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Processing and Applications of Composite Ceramic Materials for Emerging Technologies. In Advanced Ceramic Materials-Emerging Technologies; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-83634-016-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Wang, M.-S.; Bando, Y.; Golberg, D. Tensile Tests on Individual Multi-Walled Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 4895–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, Z.; Yi, C.; Zhou, H.; Park, C.; Fay, C.C.; Deng, J.; Chew, H.B.; Ke, C. Exceptionally Strong Boron Nitride Nanotube Aluminum Composite Interfaces. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2023, 59, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, N.G.; Zettl, A. Measurement of the Elastic Modulus of a Multi-Wall Boron Nitride Nanotube. Solid State Commun. 1998, 105, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dmuchowski, C.M.; Park, C.; Fay, C.C.; Ke, C. Quantitative Characterization of Structural and Mechanical Properties of Boron Nitride Nanotubes in High Temperature Environments. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tank, M.J.; Reyes, A.N.; Park, J.G.; Scammell, L.R.; Smith, M.W.; De Leon, A.; Sweat, R.D. Extreme Thermal Stability and Dissociation Mechanisms of Purified Boron Nitride Nanotubes: Implications for High-Temperature Nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 12444–12453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Shi, Q.; Chen, J. Research on BNNTs/Epoxy/Silicone Ternary Composite Systems for High Thermal Conductivity. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 381, 012076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumings, J.; Zettl, A. Field Emission and Current-Voltage Properties of Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Solid State Commun. 2004, 129, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Sauti, G.; Park, C.; Yamakov, V.I.; Wise, K.E.; Lowther, S.E.; Fay, C.C.; Thibeault, S.A.; Bryant, R.G. Multifunctional Electroactive Nanocomposites Based on Piezoelectric Boron Nitride Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 11942–11950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Dmuchowski, C.M.; Jiang, Y.; Yi, C.; Gou, F.; Deng, J.; Ke, C.; Chew, H.B. Sliding Energy Landscape Governs Interfacial Failure of Nanotube-Reinforced Ceramic Nanocomposites. Scr. Mater. 2022, 210, 114413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Bagchi, S.; Gou, F.; Dmuchowski, C.M.; Park, C.; Fay, C.C.; Chew, H.B.; Ke, C. Direct Nanomechanical Measurements of Boron Nitride Nanotube—Ceramic Interfaces. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 025706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Bi, J.-Q.; Wang, W.-L.; Sun, X.-L.; Long, N.-N. Microstructure and Properties of SiO2 Matrix Reinforced by BN Nanotubes and Nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 9996–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K.; Singh, S.; Choudhary, S.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, A.; Li, L.H.; Chen, Y.; Keshri, A.K. Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of Plasma Sprayed Boron Nitride Nanotubes Reinforced Alumina Coating. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 9194–9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, M.; Leon, A.D.; Huang, W.; Patadia, M.; Degraff, J.; Sweat, R. Manufacturing of Stereolithographic 3D Printed Boron Nitride Nanotube-Reinforced Ceramic Composites with Improved Thermal and Mechanical Performance. Funct. Compos. Struct. 2023, 5, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.; Wang, D.; Gou, F.; Ke, C. Boron Nitride Nanotubes Toughen Silica Ceramics. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2024, 2, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Chen, R.; Liu, A.; Anjum, N.; Liu, Y.; Ning, F.; Ke, C. Enhancing the Strength and Toughness of 3D-Printed Alumina Reinforced with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 9481–9491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.; Wang, D.; Ke, C. Toughening Polymer-Derived Ceramics with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2025, 3, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, R.; Anjum, N.; Ke, C. Thermal Expansion of Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Additively Manufactured Ceramic Nanocomposites. Nanotechnology 2024, 36, 065703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Anjum, N.; Jiang, Y.; Ke, C. Anisotropic Mechanical Enhancements of Additively Manufactured Silica with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 65702–65713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmairat, O.Q.; Gou, F.; Dmuchowski, C.M.; Chiarot, P.R.; Park, C.; Miles, R.N.; Ke, C. Quantifying the Interfacial Load Transfer in Electrospun Carbon Nanotube Polymer Nanocomposite Microfibers by Using in situ Raman Micromechanical Characterization Techniques. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 365302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, N.; Alsmairat, O.Q.; Liu, Z.; Park, C.; Fay, C.C.; Ke, C. Mechanical Characterization of Electrospun Boron Nitride Nanotube-Reinforced Polymer Nanocomposite Microfibers. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 4594–4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen Ginestra, C.J.; Martínez-Jiménez, C.; Matatyaho Ya’akobi, A.; Dewey, O.S.; Smith McWilliams, A.D.; Headrick, R.J.; Acapulco, J.A.; Scammell, L.R.; Smith, M.W.; Kosynkin, D.V.; et al. Liquid Crystals of Neat Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Their Assembly into Ordered Macroscopic Materials. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Park, C.; Fay, C.C.; Wang, X.; Ke, C. Mechanical Strength of Boron Nitride Nanotube-Polymer Interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 253105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Bao, B.; Xu, J.; Zhou, W. Controlled Hydrophilic/Hydrophobic Property of Silica Films by Manipulating the Hydrolysis and Condensation of Tetraethoxysilane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 376, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, R.; Subbotin, A.; Cuperus, L.; Boonen, P.; Dorschu, M.; Oosterlinck, F.; Bulters, M. Fiber Diameter Control in Electrospinning. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 173105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Yang, J.-F.; Kondo, N.; Ohji, T.; Kanzaki, S.; Deng, Z.-Y. High-Strength Porous Silicon Carbide Ceramics by an Oxidation-Bonding Technique. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 85, 2852–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geltmeyer, J.; De Roo, J.; Van den Broeck, F.; Martins, J.C.; De Buysser, K.; De Clerck, K. The Influence of Tetraethoxysilane Sol Preparation on the Electrospinning of Silica Nanofibers. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2016, 77, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.S.; Atwater, B.; Pike, R.D.; Williamson, K.E.; Kranbuehl, D.E.; Schniepp, H.C. High-Purity Boron Nitride Nanotubes via High-Yield Hydrocarbon Solvent Processing. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 8351–8357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Shan, H.; Zong, D.; Yu, X.; Yin, X.; Si, Y.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Fire-Resistant and Hierarchically Structured Elastic Ceramic Nanofibrous Aerogels for Efficient Low-Frequency Noise Reduction. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Ajayi, T.D.; Xu, C. Dielectric Properties of Polymer-derived Ceramic Reinforced with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 5731–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, W.; Tański, T. Analysis of the Morphology, Structure and Optical Properties of 1D SiO2 Nanostructures Obtained with Sol-Gel and Electrospinning Methods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 489, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliahmad, N.; Biswas, P.K.; Wable, V.; Hernandez, I.; Siegel, A.; Dalir, H.; Agarwal, M. Electrospun Thermosetting Carbon Nanotube–Epoxy Nanofibers. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Bi, J.-Q.; Wang, W.-L.; Sun, X.-L.; Long, N.-N.; Bai, Y.-J. Fabrication and Mechanical Properties of SiO2–Al2O3–BNNPs and SiO2–Al2O3–BNNTs Composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 530, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-L.; Bi, J.-Q.; Wang, S.-R.; Sun, K.-N.; Du, M.; Long, N.-N.; Bai, Y.-J. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Alumina Ceramics Reinforced by Boron Nitride Nanotubes. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bi, J.; Sun, K.; Du, M.; Long, N.; Bai, Y. Fabrication of Alumina Ceramic Reinforced with Boron Nitride Nanotubes with Improved Mechanical Properties. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 3636–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-J.; Bai, Y.-J.; Wang, W.-L.; Wang, S.-R.; Han, F.-D.; Qi, Y.-X.; Bi, J.-Q. Toughening and Reinforcing Zirconia Ceramics by Introducing Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 546, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Wen, D.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Guo, P. Mechanical Properties and Thermal Shock Resistance Analysis of BNNT/Si3N4 Composites. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2018, 25, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gommans, H.H.; Alldredge, J.W.; Tashiro, H.; Park, J.; Magnuson, J.; Rinzler, A.G. Fibers of Aligned Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Polarized Raman Spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Prestat, E.; Hashimoto, T.; Guan, J.; Kim, K.S.; Kingston, C.T.; Simard, B.; Young, R.J. Reinforcement of Polymer-Based Nanocomposites by Thermally Conductive and Electrically Insulating Boron Nitride Nanotubes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Lu, M.; Arias-Monje, P.J.; Luo, J.; Park, C.; Kumar, S. Determining the Orientation and Interfacial Stress Transfer of Boron Nitride Nanotube Composite Fibers for Reinforced Polymeric Materials. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 6670–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Park, C.; Fay, C.C.; Stupkiewicz, S.; Ke, C. Mechanical Deformations of Boron Nitride Nanotubes in Crossed Junctions. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 164305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuok, M.H.; Lim, H.S.; Ng, S.C.; Liu, N.N.; Wang, Z.K. Brillouin Study of the Quantization of Acoustic Modes in Nanospheres. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 90, 255502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | 0 wt.% BNNT | 0.1 wt.% BNNT | 0.3 wt.% BNNT | 0.5 wt.% BNNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 40.6 ± 3.0 | 42.0 ± 4.0 | 47.8 ± 4.6 | 51.3 ± 5.7 |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 187.1 ± 20.2 | 190.4 ± 14.4 | 212.0 ± 20.1 | 223.3 ± 16.5 |

| Toughness (kJ/m3) | 430.9 ± 41.2 | 431.1 ± 24.0 | 470.7 ± 43.7 | 486.0 ± 43.9 |

| Breaking Strain (‰) | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.4 |

| Maximum IFSS (MPa) | - | 318.0 ± 34.4 | 337.9 ± 32.0 | 340.8 ± 33.7 |

| 0.1 wt.% BNNT | 0.3 wt.% BNNT | 0.5 wt.% BNNT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample No. | p (%) | θ (°) | Probability-Weighted Average Angle (°) | p (%) | θ (°) | Probability-Weighted Average Angle (°) | p (%) | θ (°) | Probability-Weighted Average Angle (°) |

| 1 | 96.4 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 89.7 | 13.4 | 6.6 | 84.8 | 24.7 | 13.8 |

| 2 | 96.6 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 90.2 | 15.3 | 7.4 | 84.6 | 24.7 | 13.8 |

| 3 | 95.8 | 8.4 | 3.3 | 91.0 | 14.4 | 6.8 | 84.5 | 25.4 | 14.3 |

| 4 | 95.9 | 8.0 | 3.1 | 90.7 | 14.0 | 6.7 | 83.9 | 22.2 | 12.6 |

| Average and deviation | - | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.3 | - | 14.3 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | - | 24.2 ± 1.4 | 13.6 ± 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, D.; Anjum, N.; Liu, Z.; Ke, C. Mechanical Enhancements of Electrospun Silica Microfibers with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010069

Wang D, Anjum N, Liu Z, Ke C. Mechanical Enhancements of Electrospun Silica Microfibers with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Dingli, Nasim Anjum, Zihan Liu, and Changhong Ke. 2026. "Mechanical Enhancements of Electrospun Silica Microfibers with Boron Nitride Nanotubes" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010069

APA StyleWang, D., Anjum, N., Liu, Z., & Ke, C. (2026). Mechanical Enhancements of Electrospun Silica Microfibers with Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010069