Electronic and Optical Behaviors of Platinum (Pt) Nanoparticles and Correlations with Gamma Radiation Dose and Precursor Concentration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Nanoparticle Preparation

2.3. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

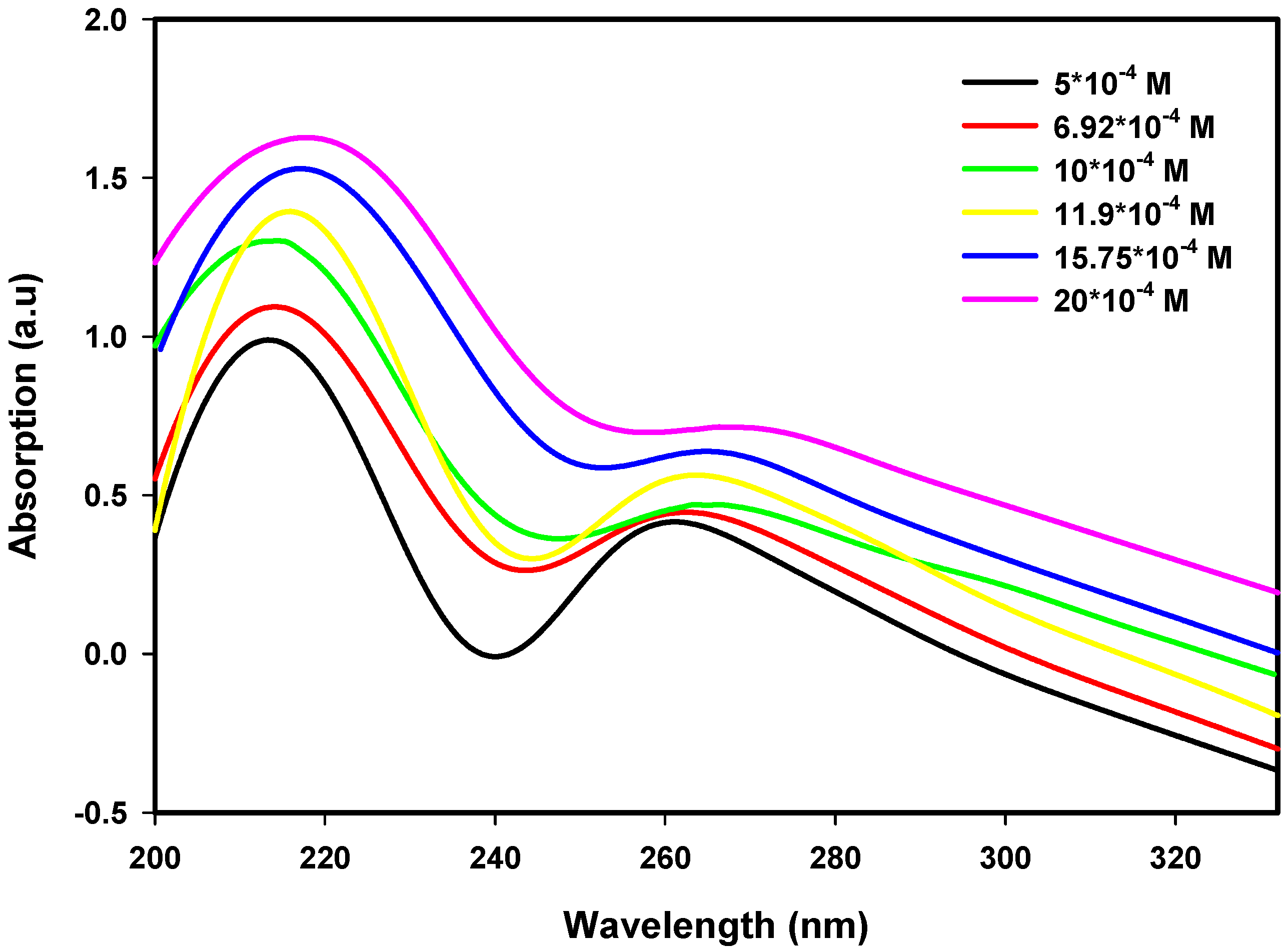

3.1. Effect of Initial Ion Concentration on Absorbance and Particle Size

3.2. Influence of Dose on Conduction Band Energy

3.3. Influence of Particle Size on Conduction Band Energy

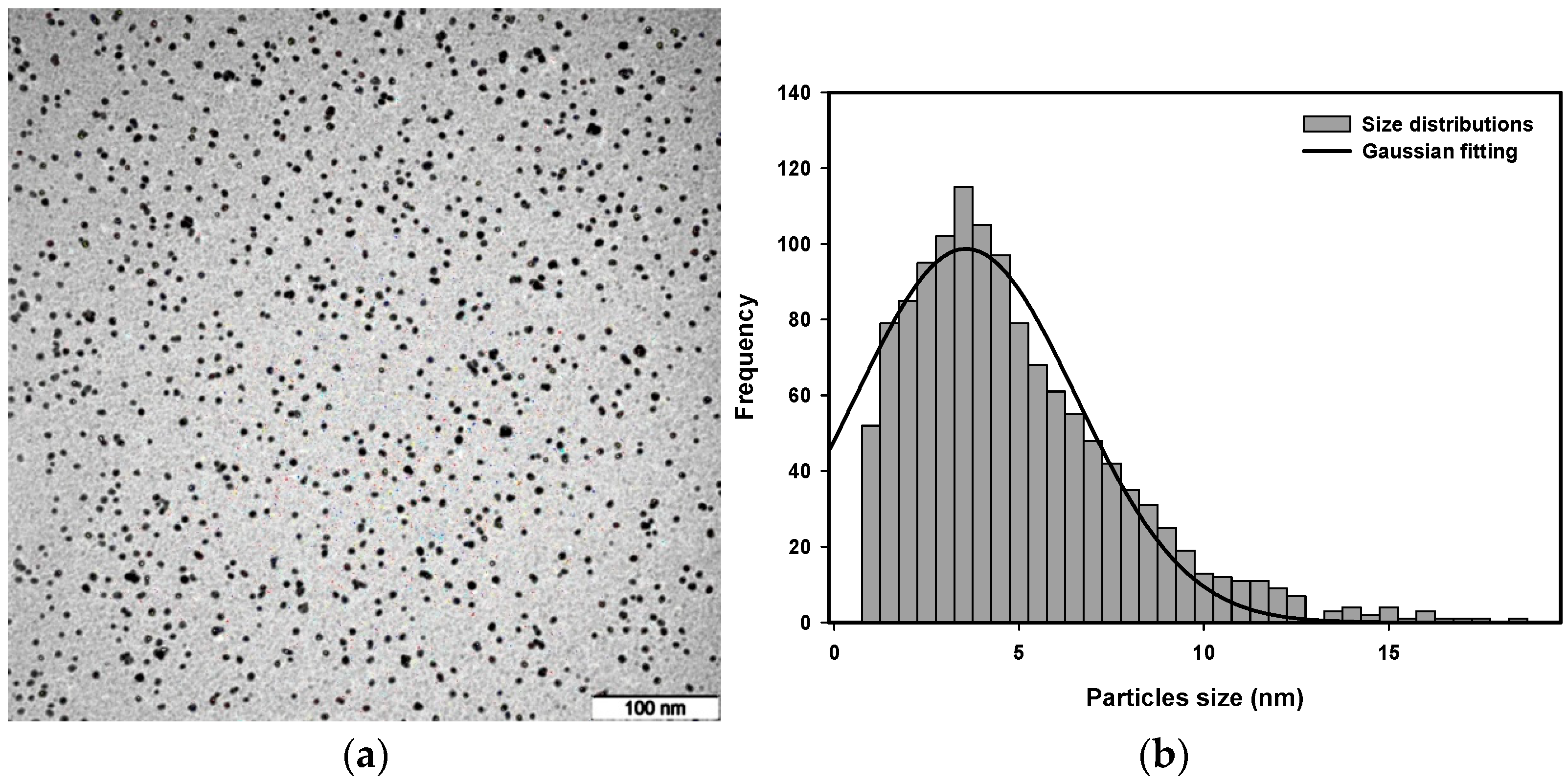

3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, A.; Holt-Hindle, P. Platinum-based nanostructured materials: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3767–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez de la Rosa, S.Y.; Muniz Diaz, R.; Villalobos Gutierrez, P.T.; Patakfalvi, R.; Gutierrez Coronado, O. Functionalized platinum nanoparticles with biomedical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istratescu, G.M.; Hayes, R.E. Ageing studies of Pt-and Pd-based catalysts for the combustion of lean methane mixtures. Processes 2023, 11, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratakis, M.; Garcia, H. Catalysis by supported gold nanoparticles: Beyond aerobic oxidative processes. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4469–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Tachibana, M.; Wada, Y.; Ota, N.; Aizawa, M. Formation of platinum nanoparticle colloidal solution by gamma-ray irradiation. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Salado-Leza, D.; Porcel, E.; González-Vargas, C.R.; Savina, F.; Dragoe, D.; Remita, H.; Lacombe, S. A facile one-pot synthesis of versatile PEGylated platinum nanoflowers and their application in radiation therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, S.A.; Preis, E.; Bakowsky, U.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Platinum nanoparticles: Green synthesis and biomedical applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guénin, E.; Fromain, A.; Serrano, A.; Gropplero, G.; Lalatonne, Y.; Espinosa, A.; Wilhelm, C. Design and evaluation of multi-core raspberry-like platinum nanoparticles for enhanced photothermal treatment. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, M.; Gurunathan, S.; Qasim, M.; Kang, M.-H.; Kim, J.-H. A comprehensive review on the synthesis, characterization, and biomedical application of platinum nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, M.; Hasan, N.; Wu, H.-F. Platinum nanoparticles for the photothermal treatment of Neuro 2A cancer cells. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 5833–5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Guan, X.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J. Recent advances in selective photothermal therapy of tumor. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belapurkar, A.; Kapoor, S.; Kulshreshtha, S.; Mittal, J. Radiolytic preparation and catalytic properties of platinum nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 2001, 36, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cele, T.; Maaza, M.; Gibaud, A. Synthesis of platinum nanoparticles by gamma radiolysis. MRS Adv. 2018, 3, 2537–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.L.; Nguyen, N.D.; Dang, V.P.; Phan, D.T.; Tran, T.H.; Nguyen, Q.H. Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles by Gamma Co-60 Ray Irradiation Method Using Chitosan as Stabilizer. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9624374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibshahi, E.; Saion, E.; Ashraf, A.; Gharibshahi, L. Size-controlled and optical properties of platinum nanoparticles by gamma radiolytic synthesis. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2017, 130, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharibshahi, E.; Saion, E.; Johnston, R.L.; Ashraf, A. Theory and experiment of optical absorption of platinum nanoparticles synthesized by gamma radiation. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2019, 147, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibshahi, E.; Saion, E. Influence of dose on particle size and optical properties of colloidal platinum nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 14723–14741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, T.-F.; Zali, N.M.; Saidin, N.U.; Kok, K.-Y.; Azhar, N. Gamma irradiation synthesis and modification of palladium supported on graphene oxide as oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalyst. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 830, 140822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokai, A.; Okitsu, K.; Hori, F.; Mizukoshi, Y.; Iwase, A. One-step synthesis of graphene-Pt nanocomposites by gamma-ray irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2016, 123, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepić, D.; Milović, M.; Sredojević, D.; Stefanović, A.; Gajić, B.; Mead, J.L.; Nardin, B.; Likozar, B.; Teržan, J.; Yasir, M. Investigation of the interactions and electromagnetic shielding properties of graphene oxide/platinum nanoparticle composites prepared under low-dose gamma irradiation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, G. Green Ammonia, Nitric Acid, Advanced Fertilizer and Electricity Production with In Situ CO2 Capture and Utilization by Integrated Intensified Nonthermal Plasma Catalytic Processes: A Technology Transfer Review for Distributed Biorefineries. Catalysts 2025, 15, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreibig, U.; Vollmer, M. Optical Properties of Metal Clusters; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Mie, G. Contributions to the optics of the turbid media, particularly of metal and colloid particles. Ann. Phys. 1908, 25, 377–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragau, A.; Miu, M.; Simion, M.; Anescu, A.; Danila, M.; Radoi, A.; Dinescu, A. Platinum nanoparticles for nanocomposite membranes preparation. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 13, 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, A.S.; Mohammed, A.M.; Khalaf, Y.H. Novel photothermal therapy using platinum nanoparticles in synergy with near-infrared radiation (NIR) against human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, H.; Gul, R.; Andleeb, A.; Ullah, S.; Shah, M.; Khanum, M.; Ullah, I.; Hano, C.; Abbasi, B.H. A detailed review on biosynthesis of platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs), their potential antimicrobial and biomedical applications. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2021, 25, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Derakhshan, M.; Karimi, M.; Shirazinia, M.; Mahjoubin-Tehran, M.; Homayonfal, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Mirzaei, S.A.; Soleimanpour, H.; Dehghani, S. Platinum nanoparticles in biomedicine: Preparation, anti-cancer activity, and drug delivery vehicles. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 797804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depciuch, J.; Stec, M.; Klebowski, B.; Maximenko, A.; Drzymała, E.; Baran, J.; Parlinska-Wojtan, M. Size effect of platinum nanoparticles in simulated anticancer photothermal therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 29, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerpude, S.T.; Potbhare, A.K.; Bhilkar, P.; Rai, A.R.; Singh, R.P.; Abdala, A.A.; Adhikari, R.; Sharma, R.; Chaudhary, R.G. Biomedical, clinical and environmental applications of platinum-based nanohybrids: An updated review. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibshahi, L.; Saion, E.; Gharibshahi, E.; Shaari, A.H.; Matori, K.A. Structural and optical properties of Ag nanoparticles synthesized by thermal treatment method. Materials 2017, 10, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibshahi, L.; Saion, E.; Gharibshahi, E.; Shaari, A.H.; Matori, K.A. Influence of Poly (vinylpyrrolidone) concentration on properties of silver nanoparticles manufactured by modified thermal treatment method. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saion, E.; Gharibshahi, E.; Naghavi, K. Size-controlled and optical properties of monodispersed silver nanoparticles synthesized by the radiolytic reduction method. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7880–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Precursor Conc. (×10−4 M) | Dose (kGy) | Avg. Particle Size (nm) | Conduction Band Energy (First Peak) (eV) | Conduction Band Energy (Second Peak) (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.0 | 80 | 4.26 | 5.82 | 4.75 |

| 10.0 | 90 | 3.74 | 5.79 | 4.72 |

| 11.9 | 100 | 3.56 | 5.80 | 4.74 |

| 15.75 | 110 | 3.51 | 5.80 | 4.75 |

| 20.0 | 120 | 3.71 | 5.80 | 4.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gharibshahi, E.; Saion, E.; Ashraf, A.; Gharibshahi, L.; Ashraf, S. Electronic and Optical Behaviors of Platinum (Pt) Nanoparticles and Correlations with Gamma Radiation Dose and Precursor Concentration. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010063

Gharibshahi E, Saion E, Ashraf A, Gharibshahi L, Ashraf S. Electronic and Optical Behaviors of Platinum (Pt) Nanoparticles and Correlations with Gamma Radiation Dose and Precursor Concentration. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleGharibshahi, Elham, Elias Saion, Ahmadreza Ashraf, Leila Gharibshahi, and Sina Ashraf. 2026. "Electronic and Optical Behaviors of Platinum (Pt) Nanoparticles and Correlations with Gamma Radiation Dose and Precursor Concentration" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010063

APA StyleGharibshahi, E., Saion, E., Ashraf, A., Gharibshahi, L., & Ashraf, S. (2026). Electronic and Optical Behaviors of Platinum (Pt) Nanoparticles and Correlations with Gamma Radiation Dose and Precursor Concentration. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010063