Plasma-Enabled Pd/C Catalysts with Rich Carbon Defects for High-Performance Phenol Selective Hydrogenation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

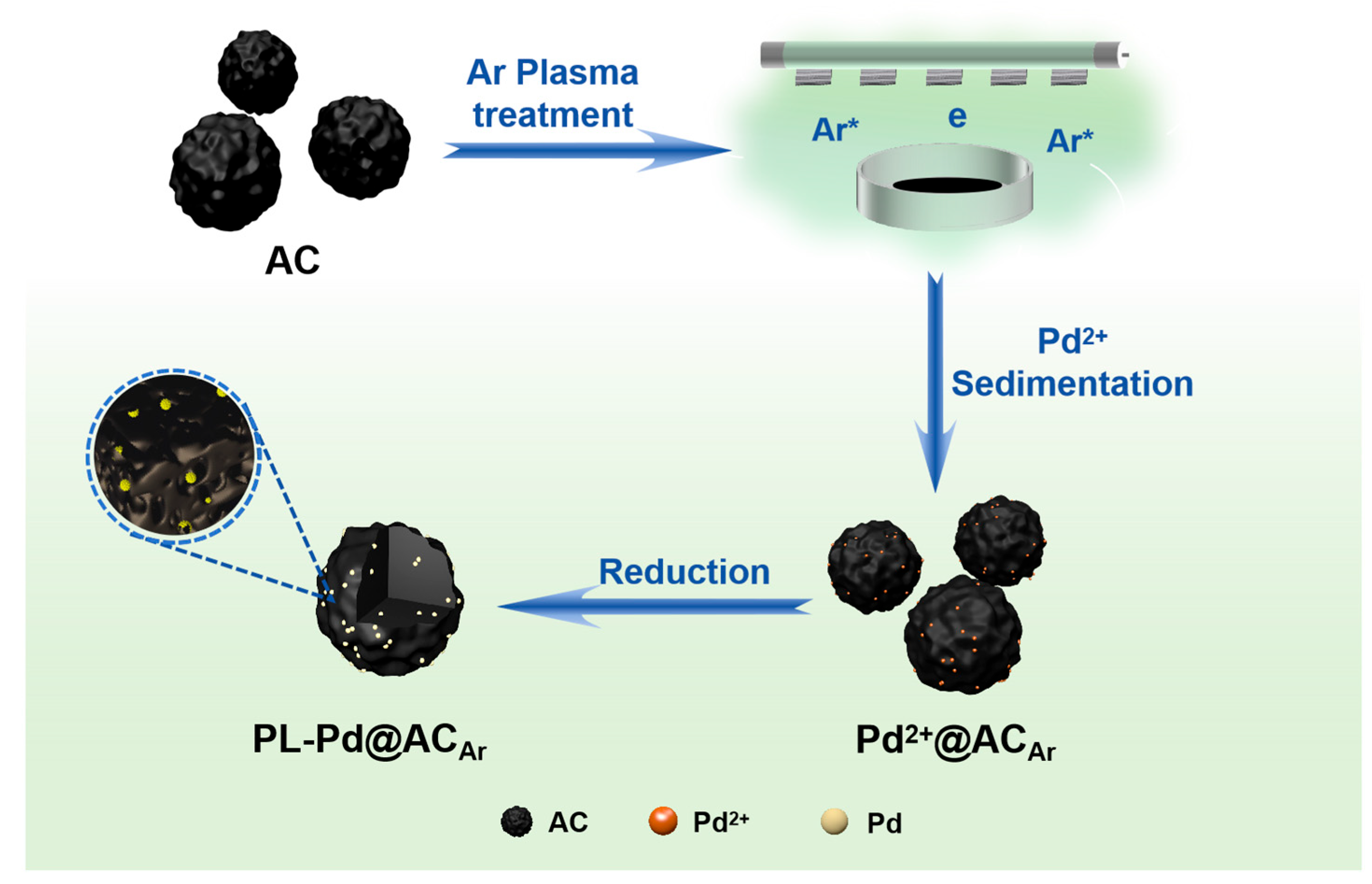

2.2. Preparation of Catalysts

2.2.1. Preparation of Argon Plasma-Treated Activated Carbon (AC-PLAr)

2.2.2. Preparation of PL-Pd@ACAr Catalyst

2.3. Catalytic Performance of Phenol Hydrogenation

2.4. Catalyst Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, B.; Huang, L.; Yu, S.; Ragauskas, A.J. Highly selective hydrogenation of phenol to cyclohexanone over a Pd-loaded N-doped carbon catalyst derived from chitosan. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 604, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, M.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; Liu, X.; Ni, J.; Yao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xi, S.; Wang, J. Highly dispersive tetrahedral vanadium species on pure silica ZSM-12 zeolite boosting the selective oxidation of cyclohexane into cyclohexanone. Sci. China Chem. 2024, 67, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.X.; Wong, W.K.; Qi, X.Q.; Lee, F.W. One-Step Synthesis of Cyclohexanone from Benzene with Catalyzed by Ruthenium Diaminodiphosphine Complex. Catal. Lett. 2004, 92, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancheti, S.V.; Yadav, G.D. CuO-ZnO-MgO as sustainable and selective catalyst towards synthesis of cyclohexanone by dehydrogenation of cyclohexanol over monovalent copper. Mol. Catal. 2021, 506, 111534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, S.G.; Ding, E.; Park, C.; Keane, M.A. Vapor phase hydrogenationof phenol over silica supported Pd and Pd-Yb catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2002, 3, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Han, J.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Ge, Q. Role of dissociation of phenol in its selective hydrogenation on Pt(111) and Pd(111). ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Han, B.; Liu, T.; Zhong, X.; Zhuang, G.; Wang, J. Selective phenol hydrogenation to cyclohexanone over alkali-metal-promoted Pd/TiO2 in aqueous media. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3585–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, L.; Gilarranz, M.A.; Casas, J.A.; Mohedano, A.F.; Rodríguez, J.J. Effects of support surface composition on the activity and selectivity of Pd/C catalysts in aqueous-phase hydrodechlorination reactions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 6661–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Burguete, C.; Linares-Solano, A.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F.; Salinas-Martínez de Lecea, C. The effect of oxygen surface groups on platinum dispersion in Pt/carbon catalysts. J. Catal. 1989, 115, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Park, Y.; Hwang, Y. Catalytic Hydrodechlorination of 4-Chlorophenol by Palladium-Based Catalyst Supported on Alumina and Graphene Materials. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xu, B.; Fan, G.; Zhang, K.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, X. UV Light-Assisted Synthesis of Highly Efficient Pd-Based Catalyst over NiO for Hydrogenation of o-Chloronitrobenzene. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, M. Pd Nanoparticles Immobilized on Pyridinic N-Rich Carbon Nanosheets for Promoting Suzuki Cross-Coupling Reactions. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shen, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y.; Chen, R. Palladium nanoparticles anchored on COFs prepared by simple calcination for phenol hydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 13523–13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, G.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, H. Modifying carbon nanotubes supported palladium nanoparticles via regulating the electronic metal- carbon interaction for phenol hydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 436, 131758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, L.; Li, X.; Lu, C.; Liu, H. Effect of Nitric Acid Pretreatment on the Properties of Activated Carbon and Supported Palladium Catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2005, 44, 5478–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xu, B.; Xiang, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Catalytic Performance of Nitrogen-Doped Activated Carbon Supported Pd Catalyst for Hydrodechlorination of 2,4-Dichlorophenol or Chloropentafluoroethane. Molecules 2019, 24, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chen, H.; Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y. Effect of nitrogen doping on the catalytic activity of activated carbon and distribution of oxidation products in catalytic wet oxidation of phenol. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 95, 1518–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z.; Cao, F.; Cui, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Tan, X.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, M. Vacancy-directed Pt-N3Cl coordination engineering via flash joule heating for chemoselective nitroarene hydrogenation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 166366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Tao, L.; Wang, R.; Hankari, S.E.; Chen, R.; Wang, S.Y. Plasma-Assisted Synthesis and Surface Modification of Electrode Materials for Renewable Energy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Liu, P.; Qiu, Z.; Shen, S.; Cao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; He, X.; Xia, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Plasma Technology for Advanced Electrochemical Energy Storage. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202304168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, T.; Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Leys, C.; Schacht, E.; Dubruel, P. Nonthermal plasma technology as a versatile strategy for polymeric biomaterials surface modification: A review. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, A.; Neyts, E.C. Plasma Technology: An Emerging Technology for Energy Storage. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 1013−1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Ming, F.; Alshareef, H.N. Excellence in Energy: Applications of Plasma in Energy Conversion and Storage Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, B.; Kumar, S.; Lee, H.N.; Kumar, R. Formation of oxygen vacancies and Ti3+ state in TiO2 thin film and enhanced optical properties by air plasma treatment. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Huo, P.; Zhang, Y.P.; Cheng, D.G.; Liu, C.J. Structure and reactivity of plasma treated Ni/Al2O3 catalyst for CO2 reforming of methane. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2008, 81, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, H.J.; Rawat, R.S. Plasma surface functionalization induces nanostructuring and nitrogen-doping in carbon cloth with enhanced energy storage performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 17801–17808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zegkinoglou, I.; Divins, N.J.; Scholten, F.; Sinev, I.; Grosse, P.; Cuenya Roldan, B. Plasma-activated copper nanocube catalysts for efficient carbon dioxide electroreduction to hydrocarbons and alcohols. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4825–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, L.; Li, Z.; Park, D.-W.; Lee, B.; Zhang, X. Atmospheric-pressure cold plasma for synthesizing Pd/FeOx catalysts with enhanced low-temperature CO oxidation activity. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 56, 060301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhu, X.; Bian, Z.; Jin, T.; Hu, J.; Liu, H. Paving the way for surface modification in one-dimensional channels of mesoporous materials via plasma treatment. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015, 202, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Ren, X.; Gao, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B. Microenvironment modulation of single-atom catalysts and their roles in electrochemical energy conversion. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Cui, S.; Xu, D.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Gong, N.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, M. Interfacial Engineering of Pd Nanoparticles on Fe3O4-rGO Composite Support for High-Chemoselective Nitroaromatic Hydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 13644−13652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yan, D.; Chen, W.; Zou, Y.; Chen, R.; Zang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yao, X.; Wang, S. Insight into the design of defect electrocatalysts: From electronic structure to adsorption energy. Mater. Today 2019, 31, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla-Lahoz, S.; Jin, W.; Pastor-Pérez, L.; Carrales-Alvarado, D.; Odriozola, J.A.; Dongil, A.B.; Reina, T.R. Guaiacol hydrodeoxygenation in hydrothermal conditions using N-doped reduced graphene oxide (RGO) supported Pt and Ni catalysts: Seeking for economically viable biomass upgrading alternatives. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2021, 611, 117977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shiju, N.R. Nanocarbon catalysts: Recent understanding regarding the active sites. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lan, G.; Fu, W.; Lai, Y.; Han, W.; Tang, H.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Role of surface defects of carbon nanotubes on catalytic performance of barium promoted ruthenium catalyst for ammonia synthesis. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 41, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, G.; Huang, J.; Song, C.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, X.; Choi, H.-S.; et al. Mulberry-Inspired Nickel-Niobium Phosphide on Plasma–Defect–Engineered Carbon Support for High-Performance Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2020, 16, e2004843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Wu, D.; Wang, T.-J.; Li, J.; Deng, P.; Chen, Q.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tian, X. Single atomic cobalt electrocatalyst for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. eScience 2022, 2, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Polaki, S.R.R.; Kamruddin, M.; Jeong, S.M.; Ostrikov, K. Plasma-electric field controlled growth of oriented graphene for energy storage applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 145303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Long, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Dong, Z. Two-dimensional covalent-organic-framework-derived nitrogen-rich carbon nanosheets modified with small Pd nanoparticles for the hydrodechlorination of chlorophenols and hydrogenation of phenol. Appl. Catal. A-Gen. 2018, 568, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, F.T.L.; Miranda, M.A.R.; dos Santos, C.M.; Sasaki, J.M. The Scherrer equation and the dynamical theory of X-ray diffraction. Found. Adv. 2016, 721, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Lasluisa, J.X.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Morallón, E. Deepening the Understanding of Carbon Active Sites for ORR Using Electrochemical and Spectrochemical Techniques. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Qu, Z.; Du, Y.; Tang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xing, W.; Chen, R. Easily Recyclable Pd@CN/SiNFs Catalysts for Efficient Phenol Hydrogenation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 5313−5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, K.; Lv, M. Synergistic catalytic hydrogenation of phenol over hybrid nano-structure Pd catalyst. Mol. Catal. 2019, 478, 110567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Yang, G.X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.F.; Chen, R.Z.; Xing, W.H. Phenol Hydrogenation to Cyclohexanone over Palladium Nanoparticles Loaded on Charming Activated Carbon Adjusted by Facile Heat Treatment. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 2600–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Jiang, H.; Chen, R.Z. Well-Defined MOF-Derived Hierarchically Porous N-Doped Carbon Materials for the Selective Hydrogenation of Phenol to Cyclohexanone. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 5806–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Du, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.F.; Chen, R.Z. Controllable Structure and Basic Sites of Pd@N-Doped Carbon Derived from Co. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 14678–14687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Pan, Z.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, H.; Chen, R.; Xing, W. Pd Nanoparticles Supported on Hierarchically Porous Carbon Nanofibers as Efficient Catalysts for Phenol Hydrogenation. Catal. Lett. 2021, 152, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.T.; Pang, F.; Ge, J.P. Synthesis of N-Doped Mesoporous Carbon Nanorods through Nano-Confined Reaction: High-Performance Catalyst Support for Hydrogenation of Phenol Derivatives. Chem.-Asian J. 2018, 13, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Shao, Y.H.; Zhang, J.X.; Jiang, H.; Chen, R.Z.Q. Insights into Microstructure and Surface Properties of Pd/C for Liquid Phase Phenol Hydrogenation to Cyclohexanone. Catal. Lett. 2023, 153, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Y.; Zhu, L.H.; Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Li, K.H.; Chen, B.H. SiO2-supported Pd nanoparticles for highly efficient, selective and stable phenol hydrogenation to cyclohexanone. Mol. Catal. 2023, 538, 112975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Low, Z.X.; Shao, Y.H.; Jiang, H.; Chen, R.Z. Two-dimensional N-doped Pd/carbon for highly efficient heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.P.; Zhang, J.N.; Liu, Y.N.; Zheng, L.R.; Cao, X.Z.; He, Y.F.; Li, D.Q. Electron-deficient Pd clusters induced by spontaneous reduction of support defect for selective phenol hydrogenation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 260, 117867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

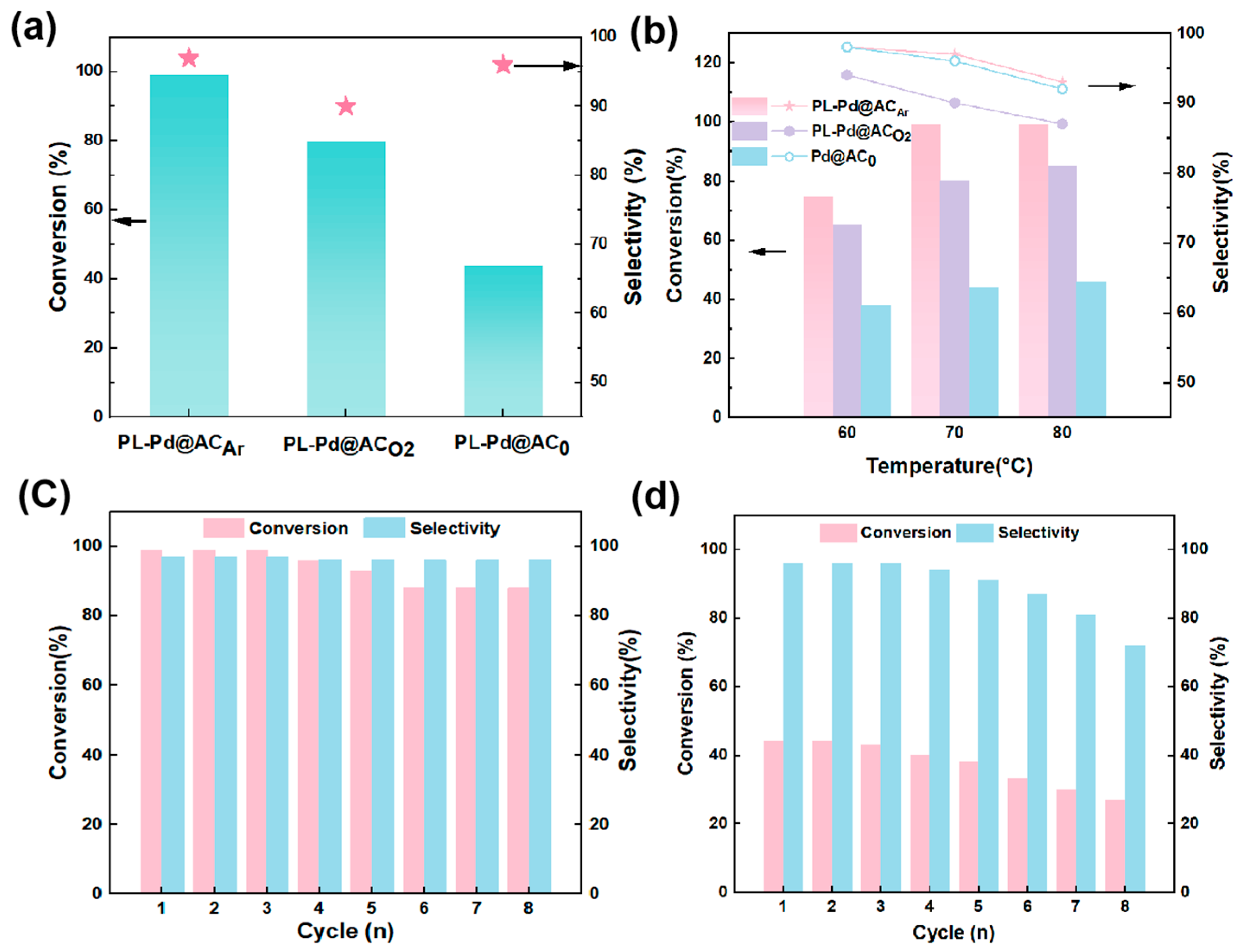

| Entry | Catalyst | Reaction Conditions [nPd:nPhenol (%), Temperature (°C), Time (h), Pressure (MPa)] | Conversion | Selectivity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PL-Pd@ACAr | 0.0047, 70 °C, 2 h, 1 MPa | 99.9 | 97 | this work |

| 2 | PL-Pd@ACO2 | 0.0047, 70 °C, 2 h, 1 MPa | 94 | 91 | this work |

| 3 | Pd@AC0 | 0.0047, 70 °C, 2 h, 1 MPa | 44.5 | 96.3 | this work |

| 4 | Pd@CN/SiNFs | 0.0090, 100 °C, 1 h, 0.1 MPa | 97.5 | 96.1 | [42] |

| 5 | Pd/@-ZrO2/AC (500) | 0.0070, 80 °C, 3 h, 0.7 MPa | 100 | 88.3 | [43] |

| 6 | Pd/AC-600 | 0.0221, 80 °C, 1 h, 0.1 MPa | 88.3 | 96 | [44] |

| 7 | Pd@CN-H | 0.0090, 80 °C, 0.83 h, 0.1 MPa | 99.8 | 90.9 | [45] |

| 8 | Pd@CN | 0.0341, 80 °C, 1 h, 0.1 MPa | 68.4 | 97.6 | [46] |

| 9 | Pd@ZCNFs-20 | 0.0284, 80 °C, 0.5 h, 0.1 MPa | 78.8 | 95 | [47] |

| 10 | Pd/N4.8-meso-CNRs | 0.0330, 40 °C, 3 h, 0.1 MPa | 93.2 | 97.3 | [48] |

| 11 | Pd/C-W | 0.0487, 80 °C, 0.33 h, 0.31 MPa | 97.2 | 97.3 | [49] |

| 12 | Pd/SiO2-2 | 0.0033, 120 °C, 1.5 h, 0.3 MPa | 80.6 | 92.1 | [50] |

| 13 | Pd@CN(1:3)- 650 | 0.1600, 80 °C, 2 h, 0.1 MPa | 94.0 | 94.7 | [51] |

| 14 | Pd/Co3O4-H | 0.0040, 80 °C, 4.5 h, 0.04 MPa | 96 | 0 | [52] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Xin, Y.; Tang, L.; Cui, S.; Duan, H.; Zhao, Q. Plasma-Enabled Pd/C Catalysts with Rich Carbon Defects for High-Performance Phenol Selective Hydrogenation. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010048

Zhang Y, Xin Y, Tang L, Cui S, Duan H, Zhao Q. Plasma-Enabled Pd/C Catalysts with Rich Carbon Defects for High-Performance Phenol Selective Hydrogenation. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu, Ying Xin, Lizheng Tang, Shihao Cui, Hongling Duan, and Qingshan Zhao. 2026. "Plasma-Enabled Pd/C Catalysts with Rich Carbon Defects for High-Performance Phenol Selective Hydrogenation" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010048

APA StyleZhang, Y., Xin, Y., Tang, L., Cui, S., Duan, H., & Zhao, Q. (2026). Plasma-Enabled Pd/C Catalysts with Rich Carbon Defects for High-Performance Phenol Selective Hydrogenation. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010048