Bismuth-Based Ceramic Processed at Ultra-Low-Temperature for Dielectric Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of the Bi-Based System

2.2. Characterization Techniques

3. Results

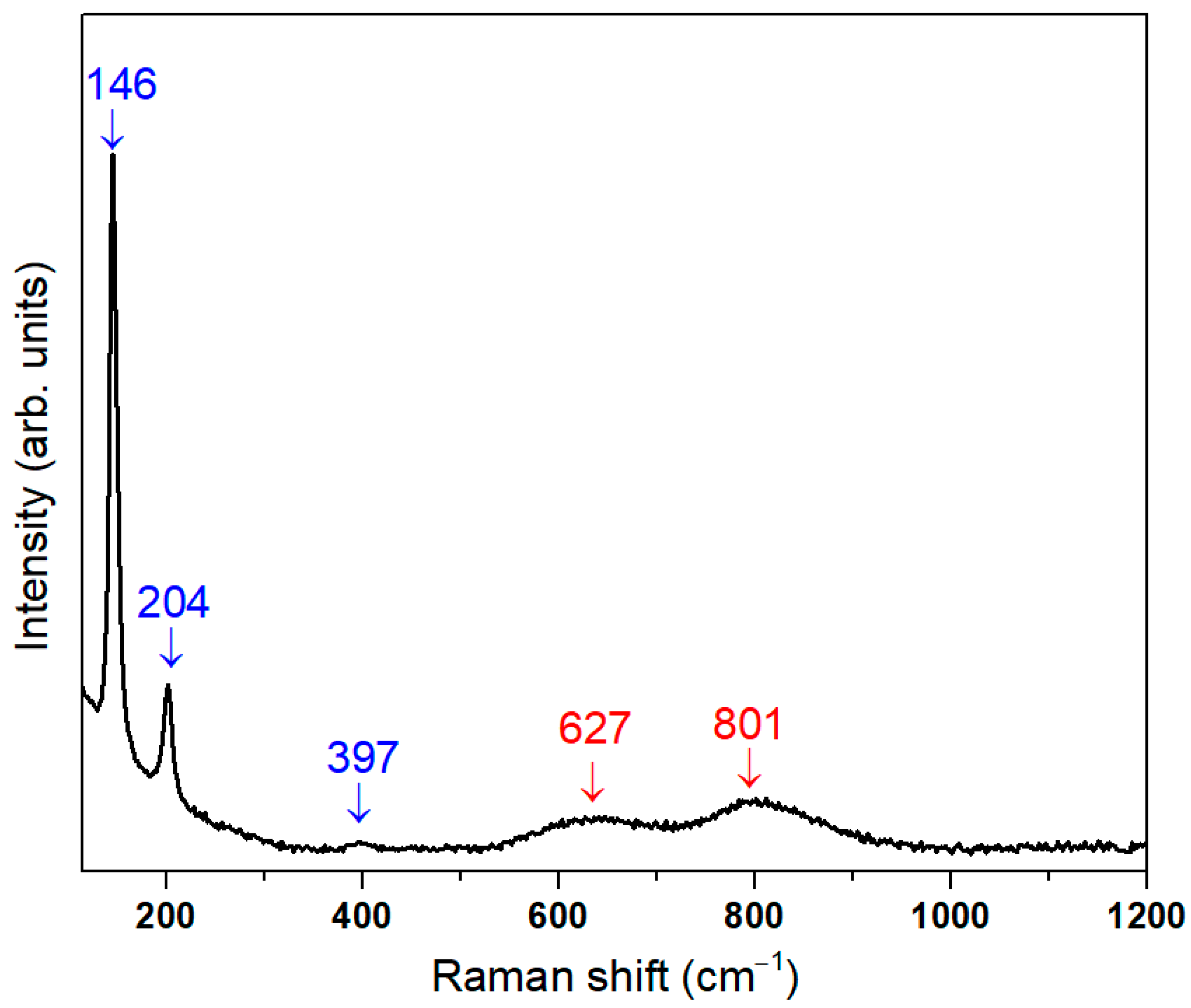

3.1. Structural Characterization

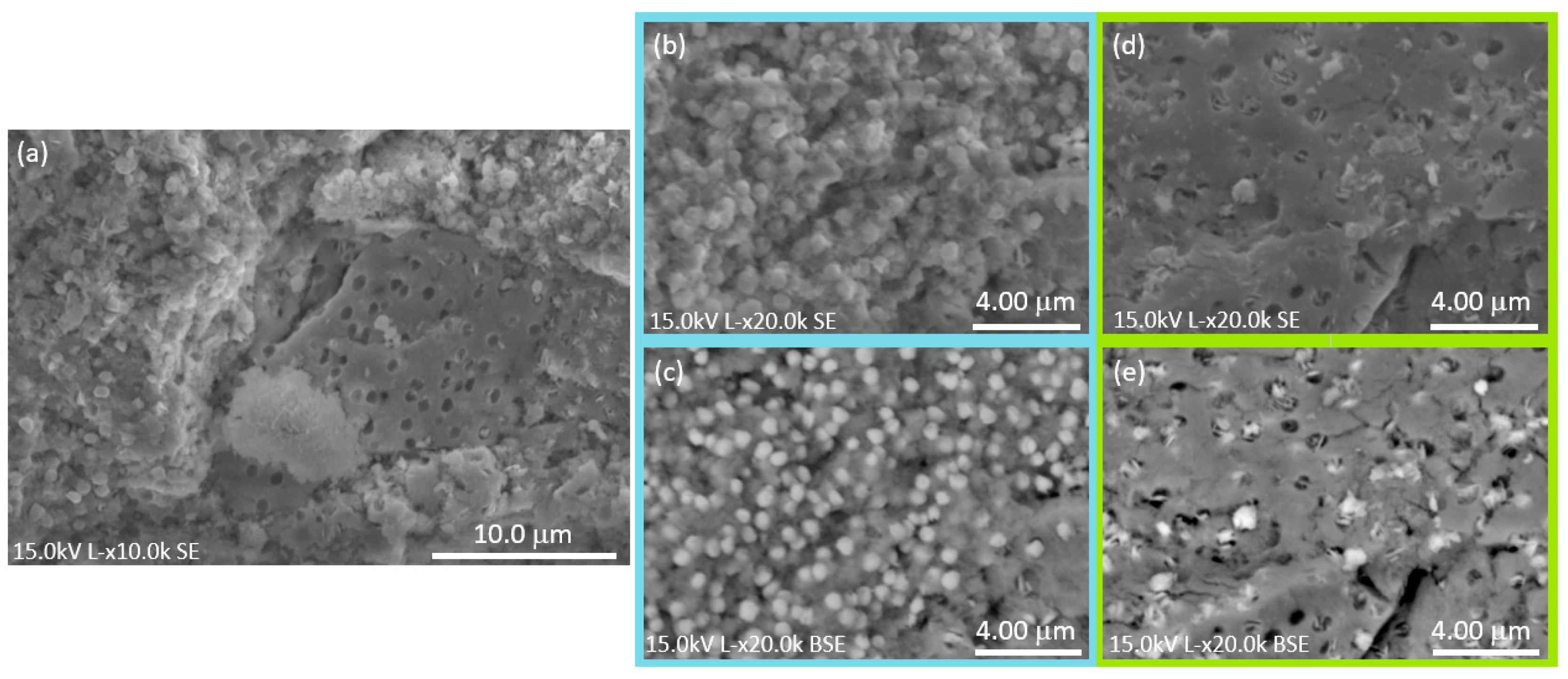

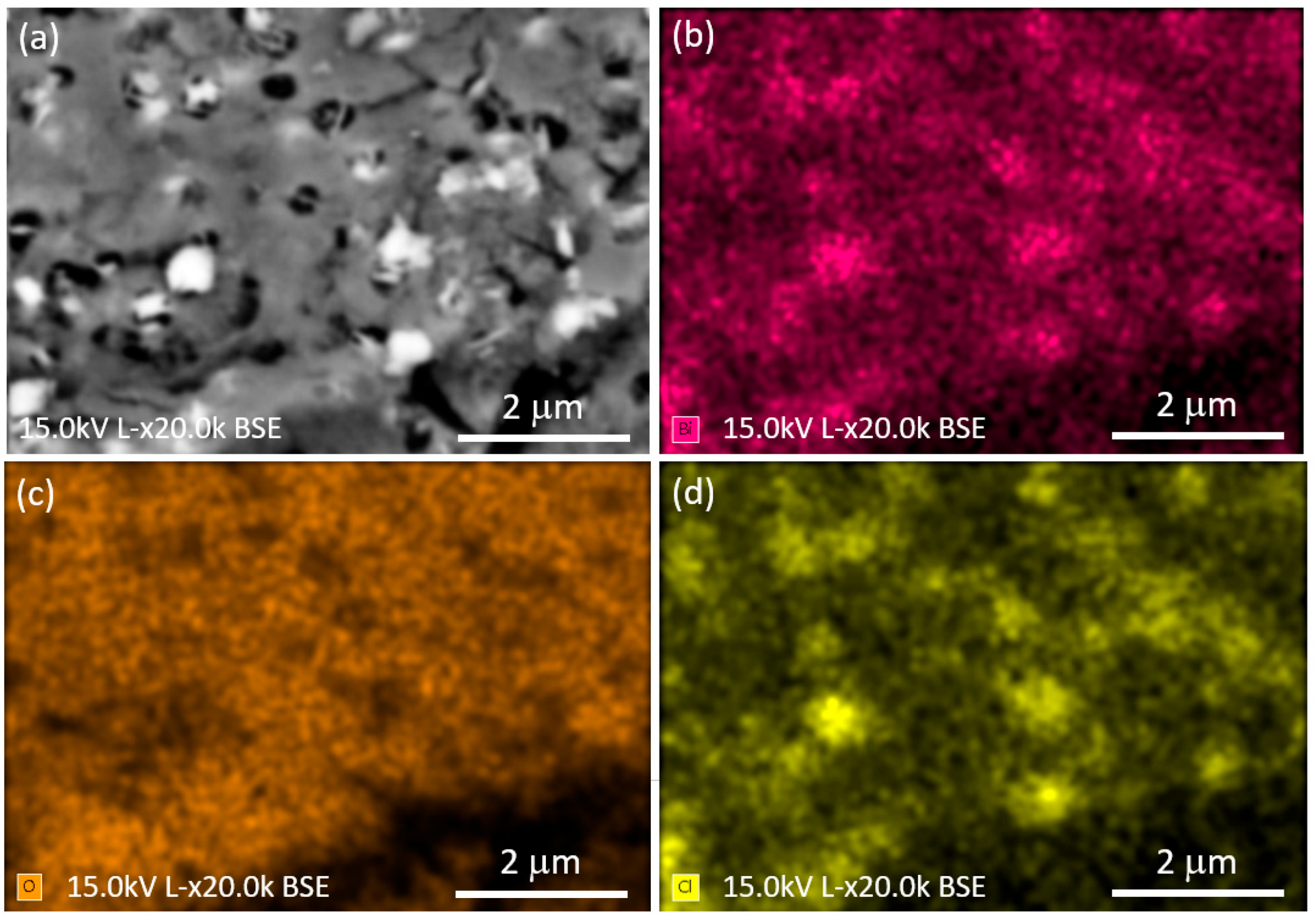

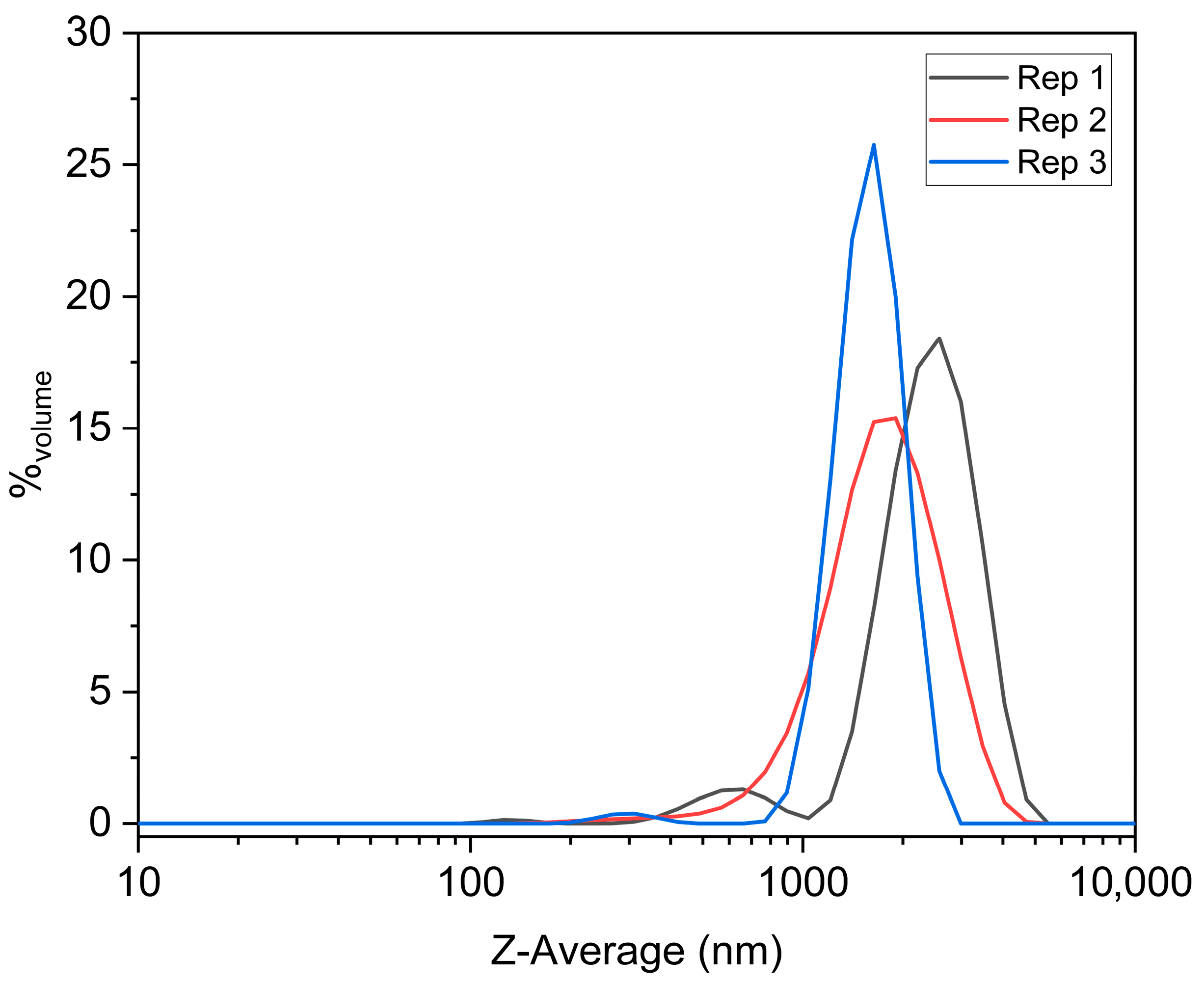

3.2. Morphological Characterization, Elemental Analysis, and Particle Size Distribution

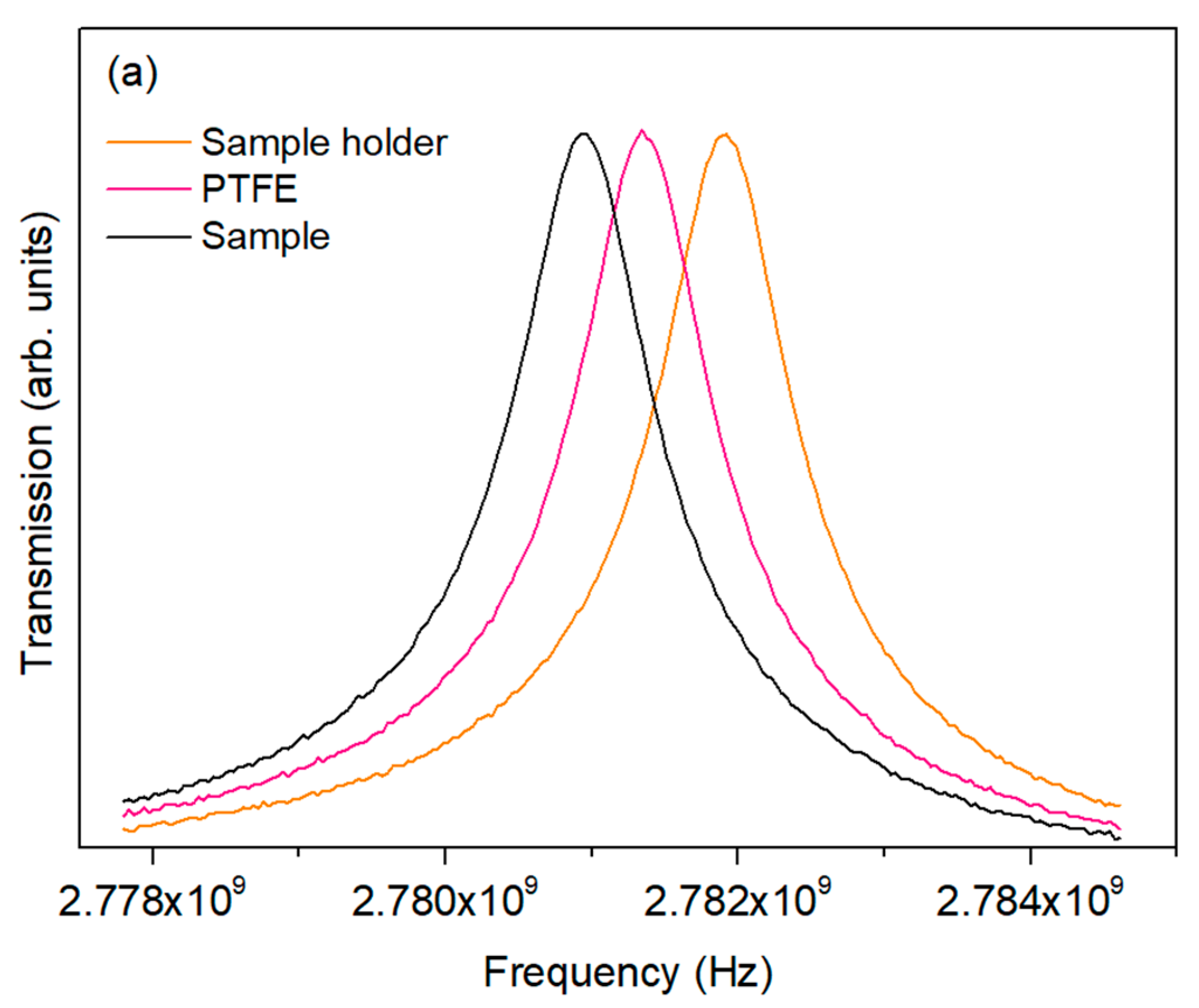

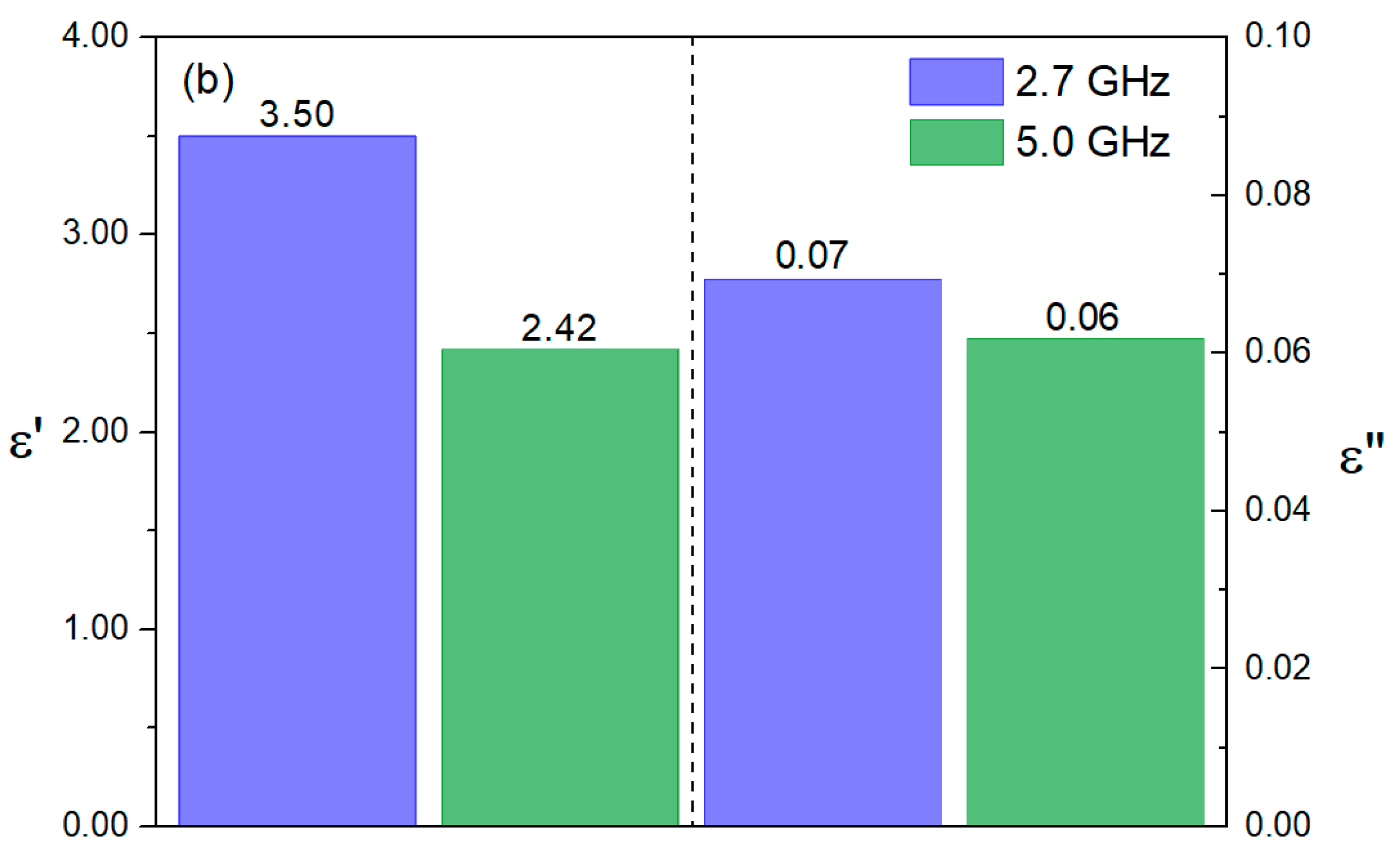

3.3. Microwave Dielectric Characterization Using the Resonant Cavity

3.4. Dielectric Characterization by Impedance Spectroscopy in the RF Range

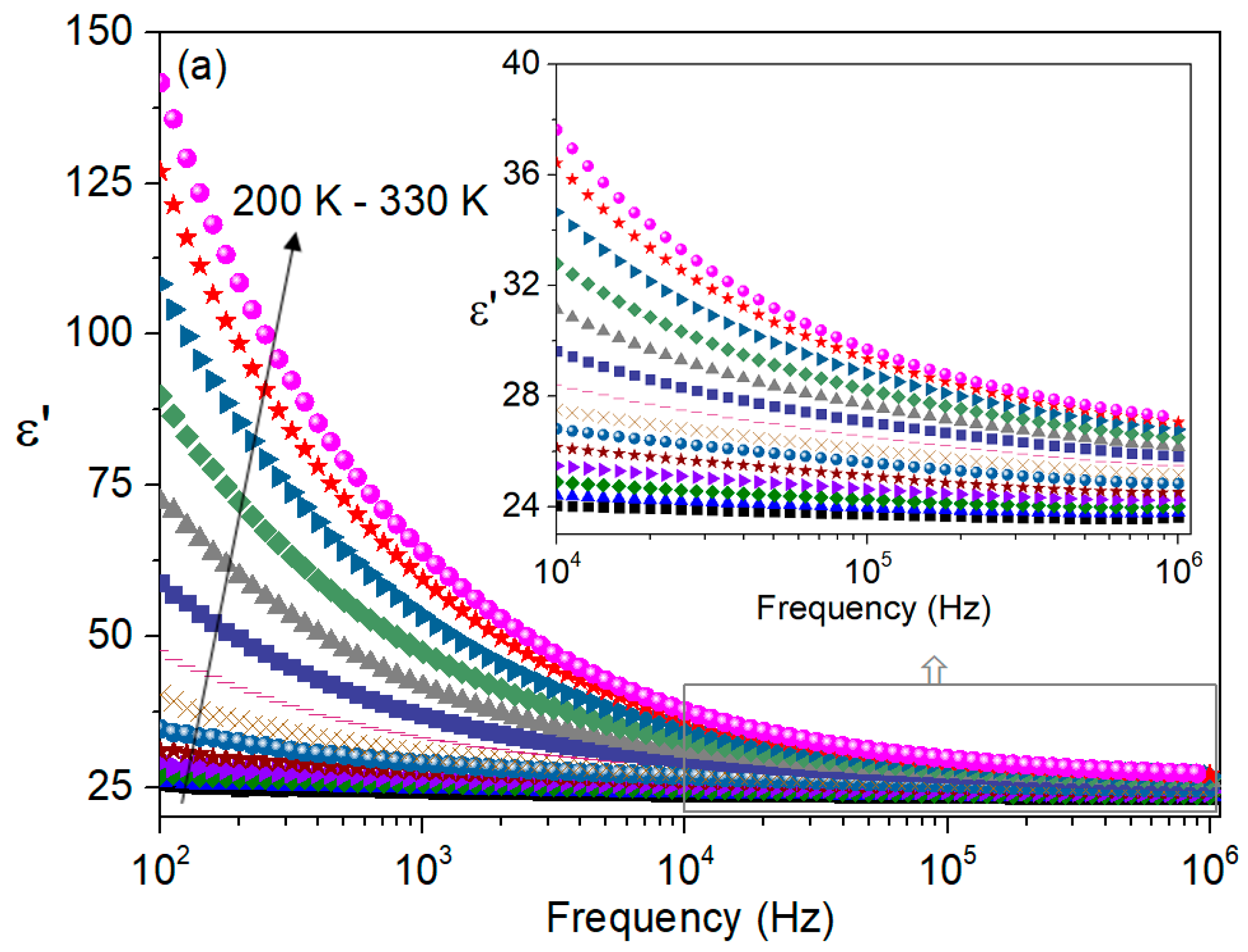

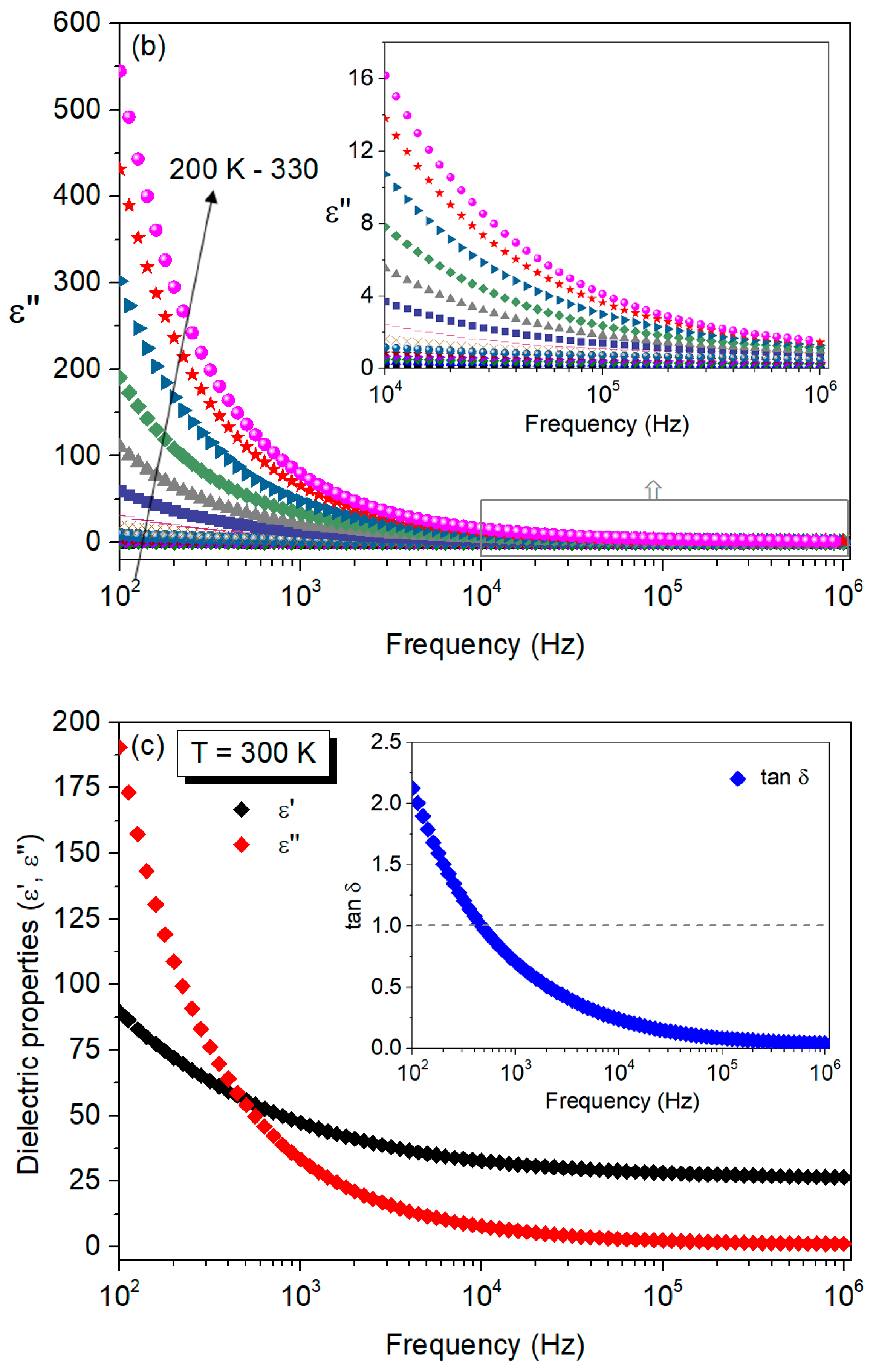

3.4.1. Dielectric Properties

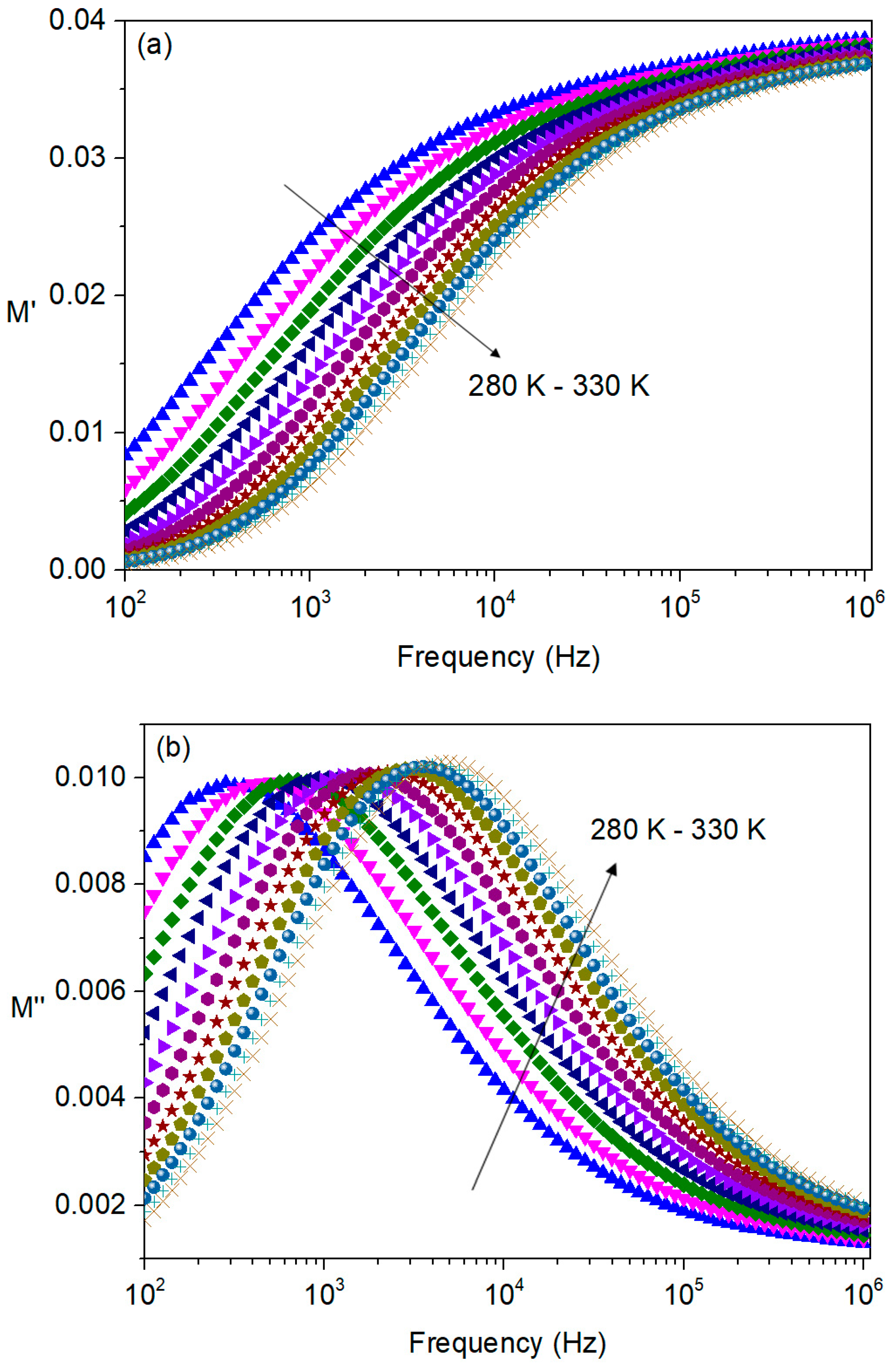

3.4.2. Electric Modulus Analysis

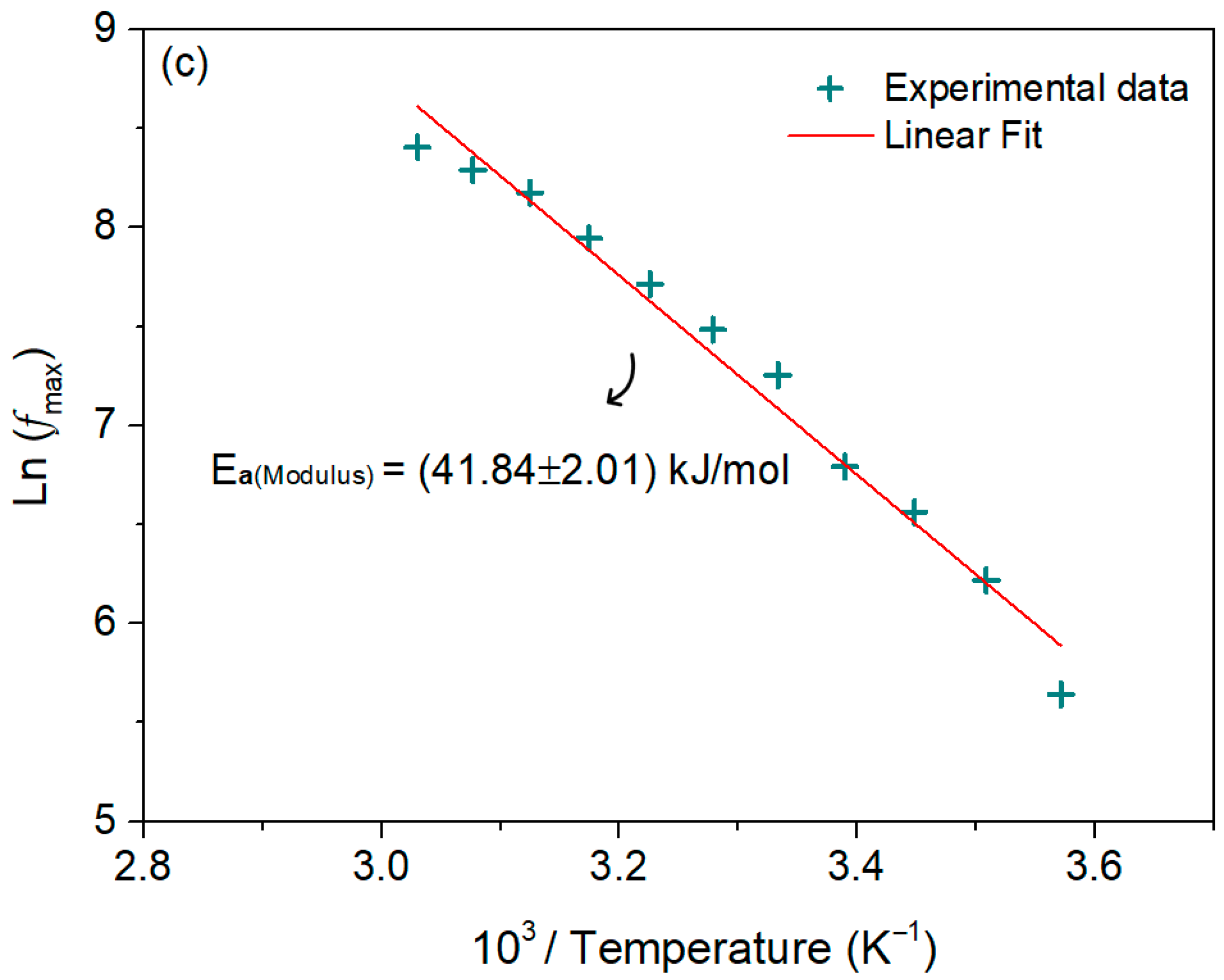

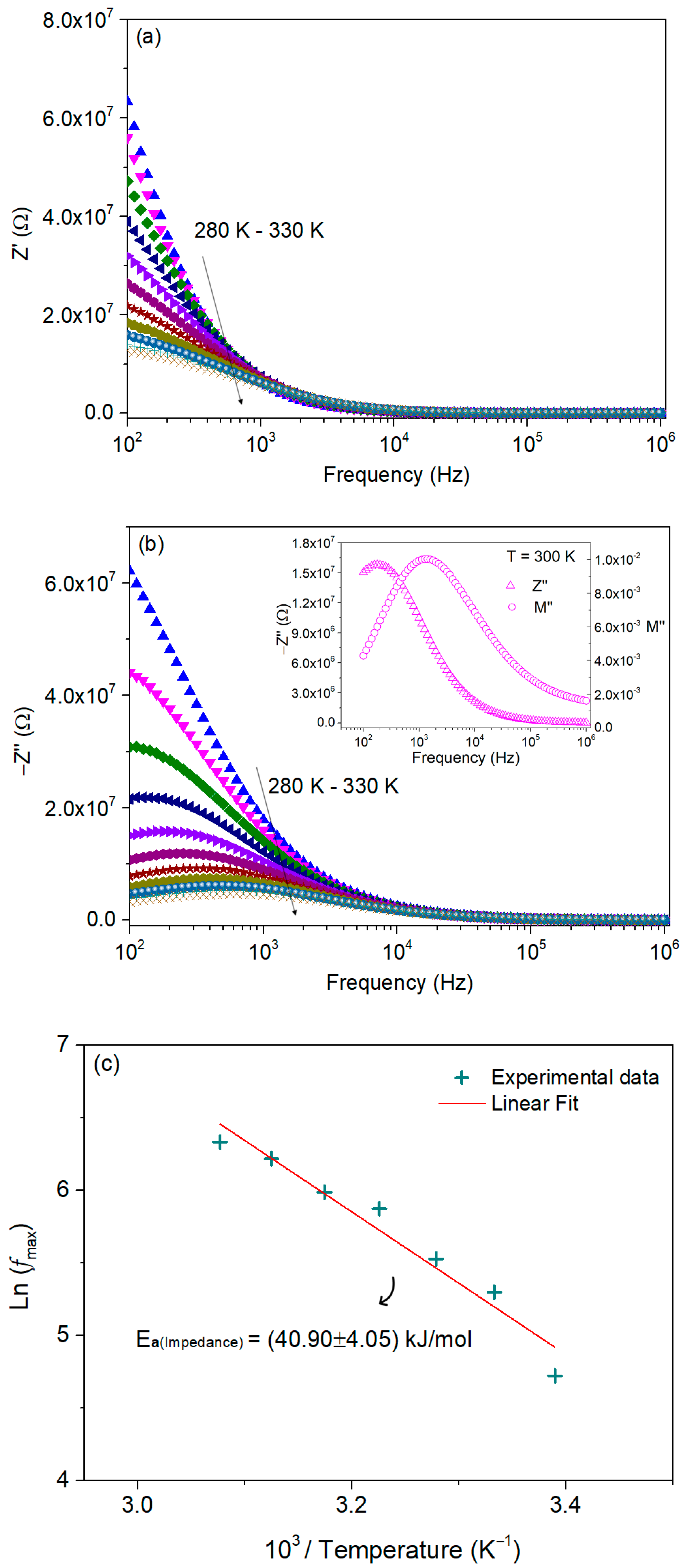

3.4.3. Complex Impedance Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sebastian, M.T.; Wang, H.; Jantunen, H. Low temperature co-fired ceramics with ultra-low sintering temperature: A review. Curr. Opin. Solid. State Mater. Sci. 2016, 20, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Q. Low loss and excellent stability of Zn0.7Mg0.3TiO3 ceramics with V2O5–TiO2 addition for application in low-temperature co-fired ceramic technology. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2025, 13, 8247–8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Zhang, K.-H.; Wang, W.; Bao, J.; Jiang, J.-P.; Zhou, K.-H.; Li, J.; Liang, C.; Liu, D.-W.; Darwish, M.A.; et al. A comprehensive study on low-temperature sintering and microwave/terahertz dielectric properties of BaO–P2O5 binary ceramics. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2025, 13, 14843–14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-H.; Qu, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X. Low-Temperature Sintering and Microwave Dielectric Properties of CuxZn1−xTi0.2Zr0.8Nb2O8 Ceramics with the Aid of LiF. Materials 2024, 17, 6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.-Q.; Miao, J.; Wu, F.-F.; Wang, W.; Bao, J.; Jiang, J.-P.; Liu, D.-W.; Darwish, M.A.; Zhou, T.; Xu, D.-M.; et al. Advancements in microwave dielectric ceramics with K20 for 5G/6G communication systems: A review. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2025, 13, 15746–15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synkiewicz-Musialska, B.; Szwagierczak, D. Impact of AlF3-CaB4O7 Doping on Terahertz Dielectric Properties and Feasibility of Low/Ultra-Low Temperature Co-Fired Ceramics. Materials 2025, 18, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althumairi, N.A.; Hjiri, M.; Aldukhayel, A.M.; Jbeli, A.; Nassar, K.I. Recent Advances in Dielectric and Ferroelectric Behavior of Ceramic Nanocomposites: Structure Property Relationships and Processing Strategies. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, L.; Du, M.; Zhan, Y. A low-sintering temperature microwave dielectric ceramic for 5G LTCC applications with ultralow loss. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 28675–28684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Mao, H.; Liu, Z.; Bai, S. Low temperature sintering and characterization of La2O3-B2O3-CaO glass-ceramic/LaBO3 composites for LTCC application. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 2382–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-F.; Zhou, D.; Xia, S.; Zhang, L.; Qiao, F.; Pang, L.-X.; Sun, S.-K.; Zhou, T.; Singh, C.; Sombra, A.S.B.; et al. Low sintering temperature, temperature-stable scheelite structured Bi[V1−x(Fe1/3W2/3)x]O4 microwave dielectric ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 5731–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, F.; Courtois, X.; Duprez, D. Tungsten-Based Catalysts for Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2021, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Wang, Q.; Fang, B. Low-Temperature Sintering of Bi(Ni0.5Ti0.5)O3-BiFeO3-Pb(Zr0.5Ti0.5)O3 Ceramics and Their Performance. Materials 2023, 16, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Li, X.; Fu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, H. Sintering characteristics, phase transitions, and microwave dielectric properties of low-firing [(Na0.5Bi0.5)xBi1−x](WxV1−x)O4 solid solution ceramics. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, S.; Amorim, C.O.; Belo, J.H.; Araújo, J.P.; Teixeira, S.S.; Graça, M.P.F.; Costa, L.C. Comprehensive Characterization of Bi1.34Fe0.66Nb1.34O6.35 Ceramics: Structural, Morphological, Electrical, and Magnetic Properties. Magnetochemistry 2024, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, S.; Graça, M.P.; Costa, L.C. Impedance Spectroscopy Study of Bi1.34Fe0.66Nb1.34O6.35 Ceramics. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 4135–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, S.; Rooney, A.P.; Graça, M.P.; Cooper, D.; Costa, L.C. Williamson-hall analysis in estimation of crystallite size and lattice strain in Bi1.34Fe0.66Nb1.34O6.35 prepared by the sol-gel method. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 263, 114830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, F.A. Crystal structure of bismuth oxyhalides. Nature 1934, 134, 856–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xie, T.; Liu, C.; Xu, L. Dy(III) Doped BiOCl Powder with Superior Highly Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Activity for Rhodamine B Photodegradation. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, C.; Cui, Y. Controllable growth of BiOCl film with high percentage of exposed {001} facets. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 289, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárdos, E.; Márta, V.A.; Fodor, S.; Kedves, E.-Z.; Hernadi, K.; Pap, Z. Hydrothermal Crystallization of Bismuth Oxychlorides (BiOCl) Using Different Shape Control Reagents. Materials 2021, 14, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, P.S.; Costa, L.C.; Devesa, S. Fabry-perot-based approach for the measurement of complex permittivity of samples inserted in resonant cavities. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2004, 43, 106–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.; Schwanzer, P.; Steiner, C.; Hagen, G.; Rabl, H.P.; Dietrich, M.; Moos, R. Mixing rules for an exact determination of the dielectric properties of engine soot using the microwave cavity perturbation method and its application in gasoline particulate filters. Sensors 2022, 22, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, J.E. (Ed.) Polymer Data Handbook, 2nd ed.; Oxford Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Vij, A.; Ahmed, F.; Kumar, A.; Hashim, M.; Koo, B.H. Dielectric properties of spinel ferrite nanostructures. In Ferrite Nanostructured Magnetic Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 599–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiva, J.; Benzarti, Z.; Carvalho, S.; Devesa, S. Green Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles—Structural, Morphological, and Dielectric Characterization. Materials 2024, 17, 5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Sarkar, B.; Pal, S. Dielectric properties and thermally activated relaxation in monovalent (Li+1) doped multiferroic GdMnO3. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Ohki, Y. Electric modulus powerful tool for analyzing dielectric behavior. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2014, 21, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malleo, D.; Nevill, J.T.; Van Ooyen, A.; Schnakenberg, U.; Lee, L.P.H. Morgan Characterization of electrode materials for dielectric spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2010, 81, 016104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadauria, P.P.S.; Kolte, J. Impedance and AC conductivity analysis of La-substituted 0.67BiFeO3–0.33BaTiO3 solid solution. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 128, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, M.K.; Dhak, D. Density of states and impedance behaviour of transition metal substituted SrBi2Nb2O9 ferroelectric nanoceramics prepared by chemical process. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017, 28, 7844–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.R.; Sahu, B.; Badapanda, T.; Pattanaik, M.S.; Kaushik, S.D.; Singh, A.K. Optical, dielectric relaxation and conduction study of Bi2Fe4O9 ceramic. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 3645–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijan, S.; Pavić, L. Solid-state impedance spectroscopy studies of dielectric properties and relaxation processes in Na2O-V2O5-Nb2O5-P2O5 glass system. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, L. Interfacial transport in lithium-ion conductors. Chin. Phys. B 2016, 25, 018202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloman, D.; Gungor, A.; Popa, A.; Stefan, M.; Macavei, S.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; Varadi, A.; Yildirim, I.D.; Suciu, R.; Nesterovschi, I.; et al. Morphological impact on the supercapacitive performance of nanostructured ZnO electrodes. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.M.G.; Faia, P.M.; Mendes, S.R.; Araújo, E.S. A Review of Impedance Spectroscopy Technique: Applications, Modelling, and Case Study of Relative Humidity Sensors Development. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faia, P.M.; Ferreira, A.J.; Furtado, C.S. Establishing and interpreting an electrical circuit representing a TiO2–WO3 series of humidity thick film sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 140, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Su, H. Low-Temperature Sintering and Electromagnetic Properties of Ferroelectric–Ferromagnetic Composites. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009, 321, 2871–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Du, W.; Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Wu, H.; Shan, L. Optical, Electrical and Microwave/Terahertz Dielectric Properties of Novel Low-Temperature Sintered Quaternary-Phase Li2O-BaO-P2O5 Pyrophosphate Ceramic for Patch Antenna Application. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 37890–37903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Feng, Q.; Jia, R.; Hu, S.; Fujita, T.; Luo, N.; You, H.; Chen, X.; Cen, Z.; Yuan, C. A Low-Temperature-Sintering Bi12SiO20 Ceramics with Ultrahigh Energy Efficiency and Breakdown Strength of ~1.05MV/Cm. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1012, 178528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafi, M.; Bin Khatab Abbasi, B.; Ahmad, S.; Abd EL-Gawaad, N.S. Temperature Dependent Charge Transport and Conduction Mechanism through Different Electroactive Regions in NiO-ZnO Heterostructure Nanocomposite by Using Impedance Spectroscopy. Ceram. Int. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Tang, M.; Wang, G.; Xu, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, X.; Xu, Z. Samarium-Modified PLZST-Based Antiferroelectric Energy Storage Ceramics for Low-Temperature Sintering in Reducing Atmosphere. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 21736–21744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T (K) | C (pF ± %) | R (MΩ ± %) | Q (ns ± %) | n (a.u. ± %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 280 | 5.48 ± 0.17 | 250 ± 0.27 | 0.204 ± 0.14 | 0.526 ± 0.04 |

| 285 | 5.30 ± 0.21 | 155 ± 0.22 | 0.203 ± 0.15 | 0.552 ± 0.04 |

| 290 | 5.34 ± 0.24 | 108 ± 0.20 | 0.264 ± 0.15 | 0.541 ± 0.04 |

| 295 | 5.34 ± 0.21 | 77.1 ± 0.14 | 0.314 ± 0.12 | 0.538 ± 0.03 |

| 300 | 5.28 ± 0.23 | 55.8 ± 0.12 | 0.360 ± 0.12 | 0.540 ± 0.03 |

| 305 | 5.40 ± 0.26 | 42.5 ± 0.12 | 0.442 ± 0.13 | 0.530 ± 0.03 |

| 310 | 5.45 ± 0.32 | 33.0 ± 0.13 | 0.508 ± 0.16 | 0.527 ± 0.04 |

| 315 | 5.32 ± 0.44 | 26.3 ± 0.15 | 0.533 ± 0.21 | 0.534 ± 0.05 |

| 320 | 5.29 ± 0.26 | 22.0 ± 0.08 | 0.605 ± 0.12 | 0.531 ± 0.03 |

| 325 | 5.26 ± 0.32 | 18.9 ± 0.10 | 0.650 ± 0.14 | 0.531 ± 0.03 |

| 330 | 5.30 ± 0.47 | 17.1 ± 0.14 | 0.714 ± 0.21 | 0.526 ± 0.05 |

| Material/System | Processing/Sintering Conditions (Temperature, Time) | ε′ | ε″ | tan δ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi–Fe–Nb oxide system | 400 °C, 4 h | 26.50 | 1.14 | 0.04 | This work |

| Ni0.37Cu0.20Zn0.43-Fe1.92O3.88 | 900 °C, 2.5 h | 15.99 | ---- | 0.019 | [37] |

| Li2BaP2O7 | 775 °C, 4 h | ≈7.1 | ≈0.22 | ≈0.03 | [38] |

| Bi12SiO20 | 800 °C, 5 h | ≈44.5 | ---- | ≈0.02 | [39] |

| NiO-ZnO | 500 °C, 4 h | ≈4.2 | ---- | ≈0.07 | [40] |

| (Pb0.92La0.02Sr0.06)[(Zr0.5Sn0.5)0.9Ti0.1]0.995O3 − 0.6%wt BASK − 0.4%wt Sm2O3 | 1040 °C, 2 h | ≈415 | ---- | ≈0.01 | [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Devesa, S.; Teixeira, S.S.; Graça, M.P.; Costa, L.C. Bismuth-Based Ceramic Processed at Ultra-Low-Temperature for Dielectric Applications. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010046

Devesa S, Teixeira SS, Graça MP, Costa LC. Bismuth-Based Ceramic Processed at Ultra-Low-Temperature for Dielectric Applications. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleDevesa, Susana, Sílvia Soreto Teixeira, Manuel Pedro Graça, and Luís Cadillon Costa. 2026. "Bismuth-Based Ceramic Processed at Ultra-Low-Temperature for Dielectric Applications" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010046

APA StyleDevesa, S., Teixeira, S. S., Graça, M. P., & Costa, L. C. (2026). Bismuth-Based Ceramic Processed at Ultra-Low-Temperature for Dielectric Applications. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010046