Green Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Materials via a Biomass-Derived Carboxylic Acid-Assisted Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica

2.3. Characterization Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

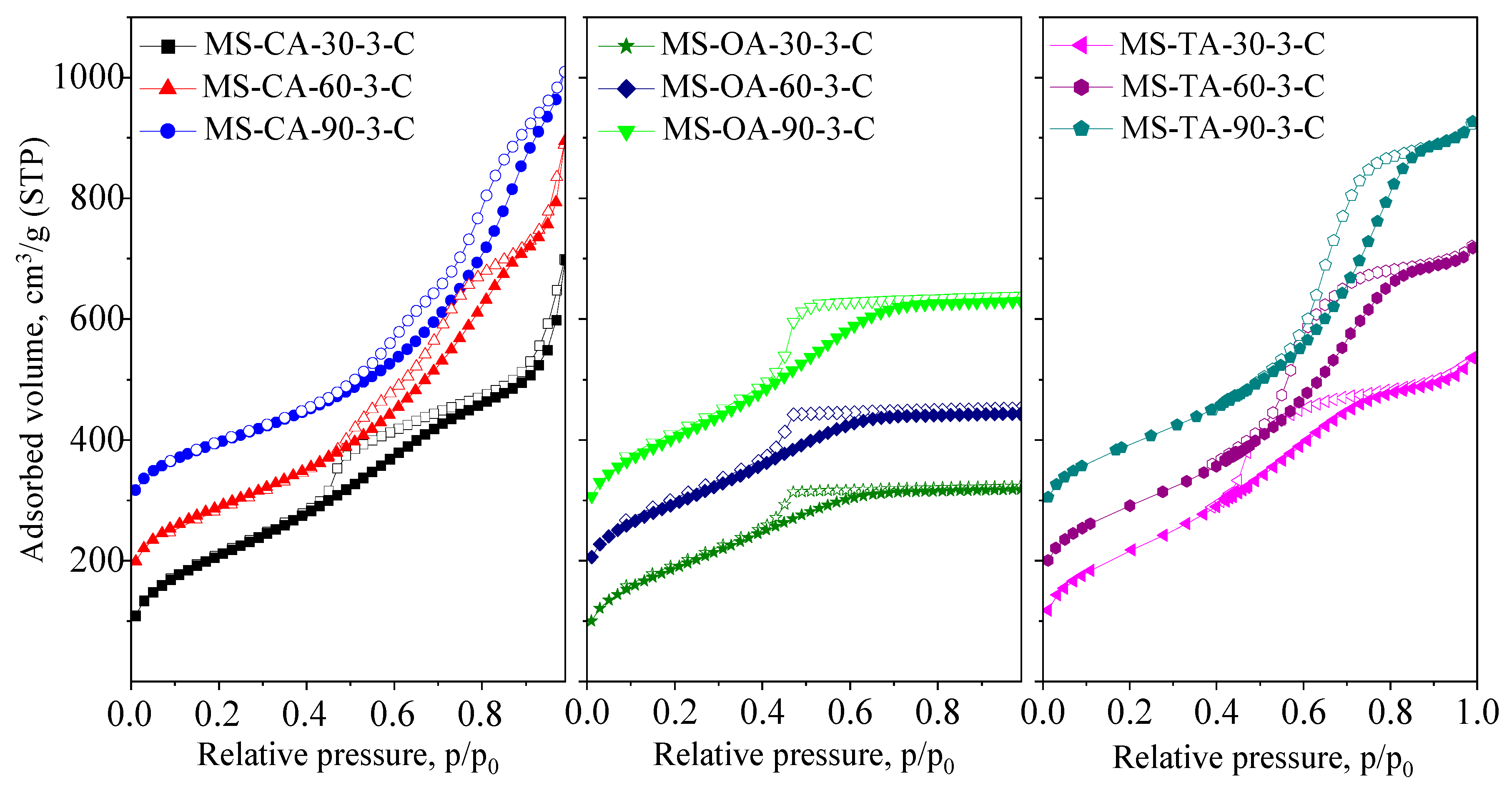

3.1. Influence of the Synthesis Conditions and Composition

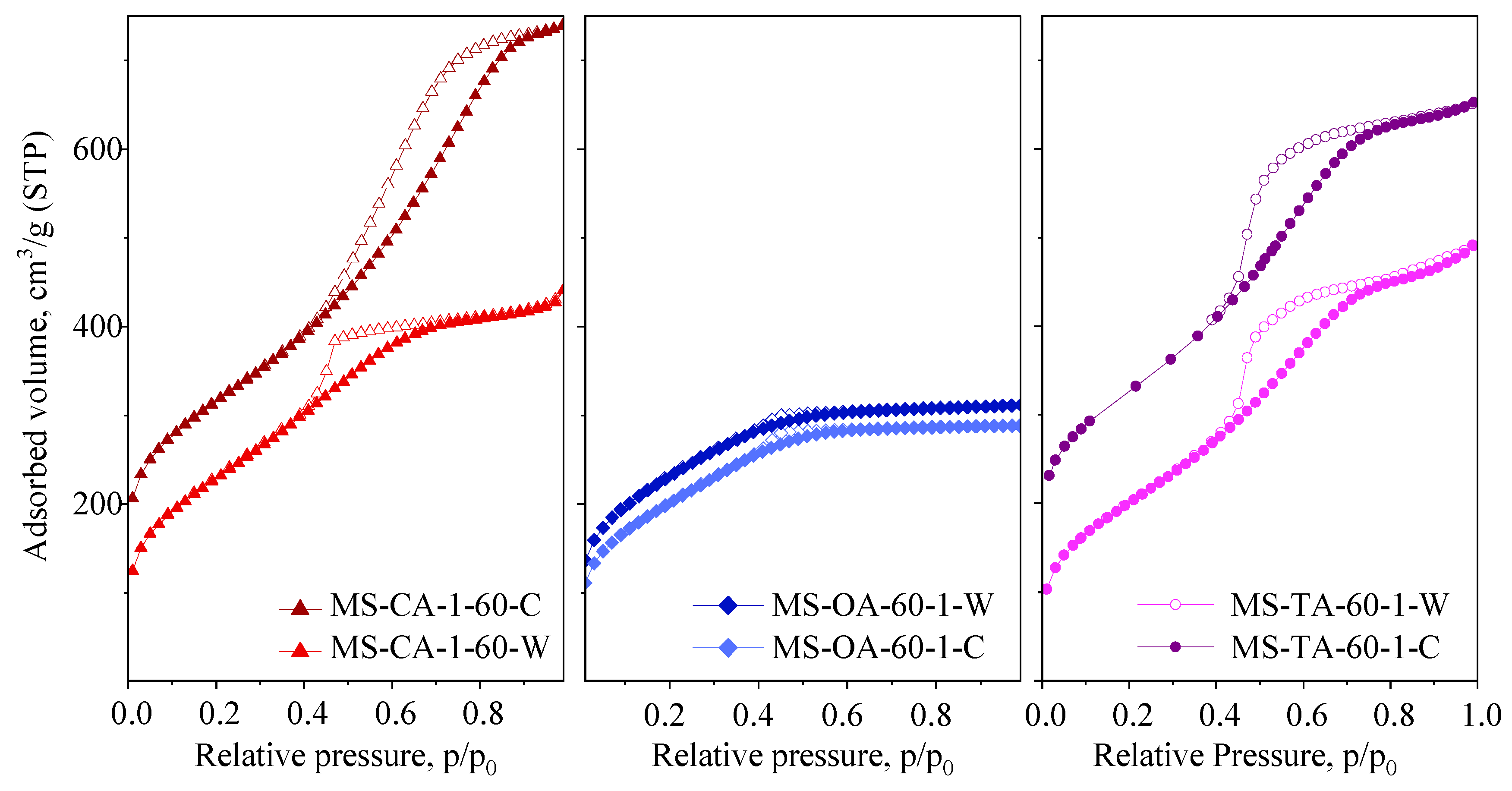

3.1.1. Effect of Drying Temperature

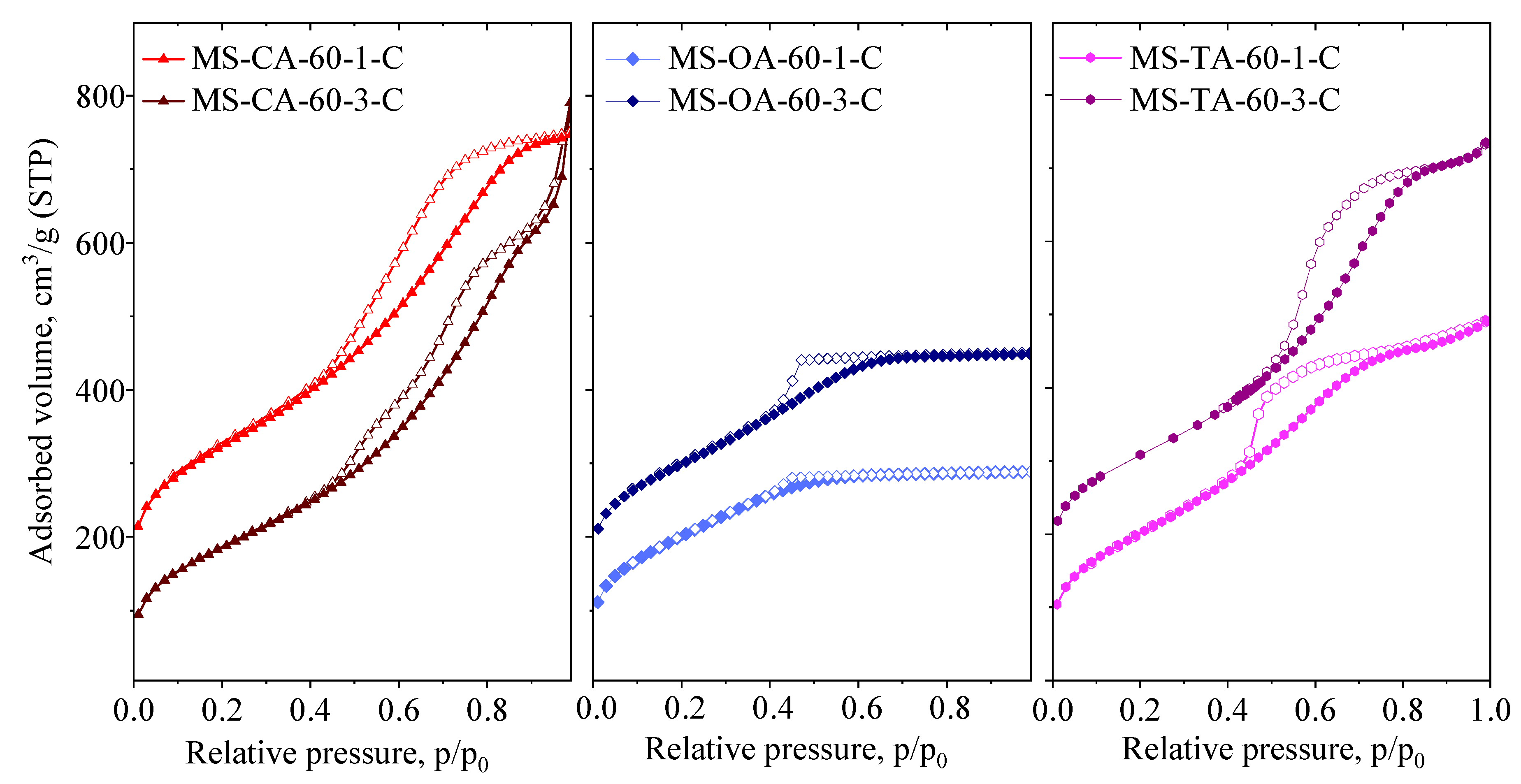

3.1.2. Effect of Acid-to-TEOS Molar Ratio

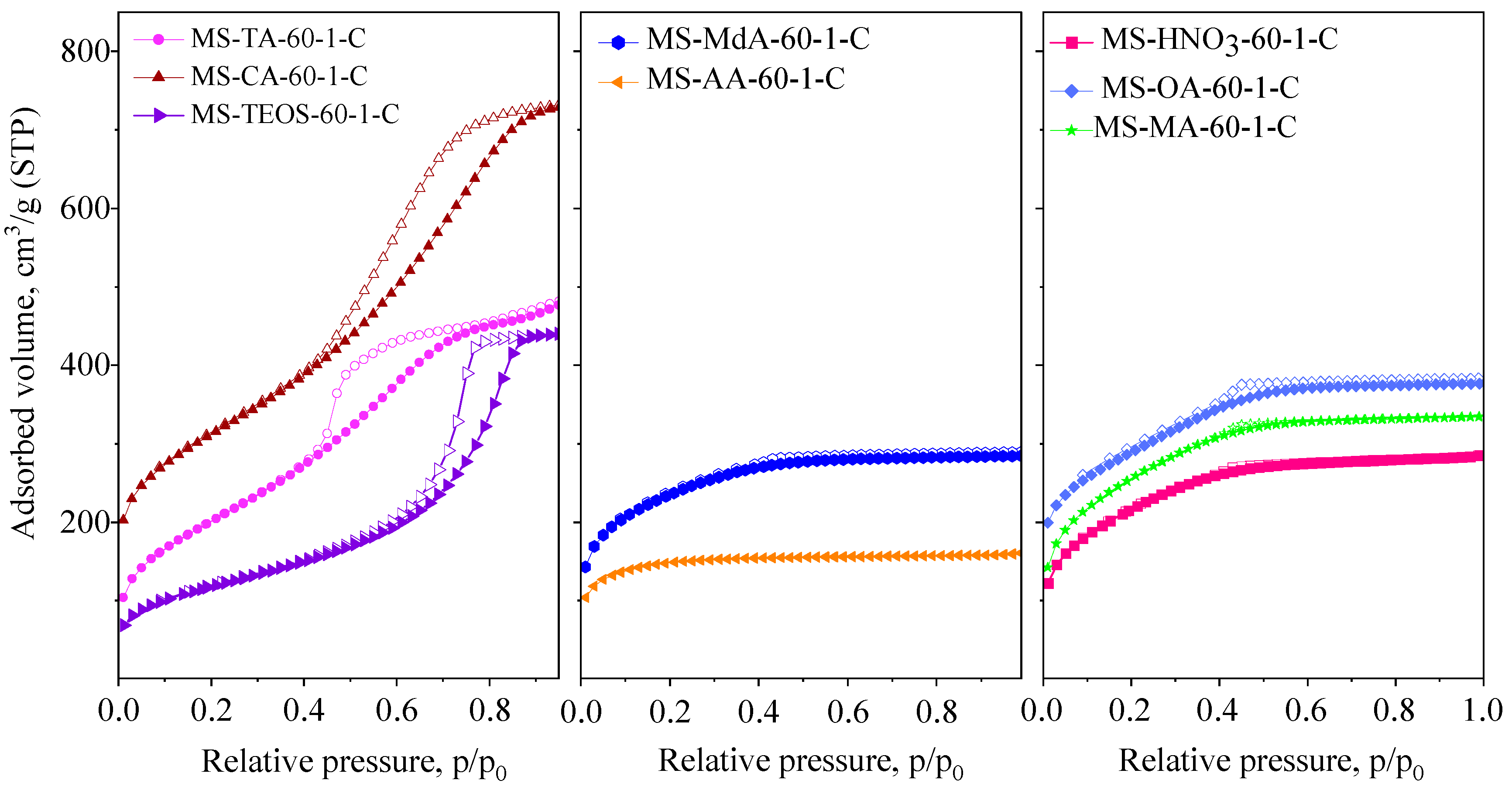

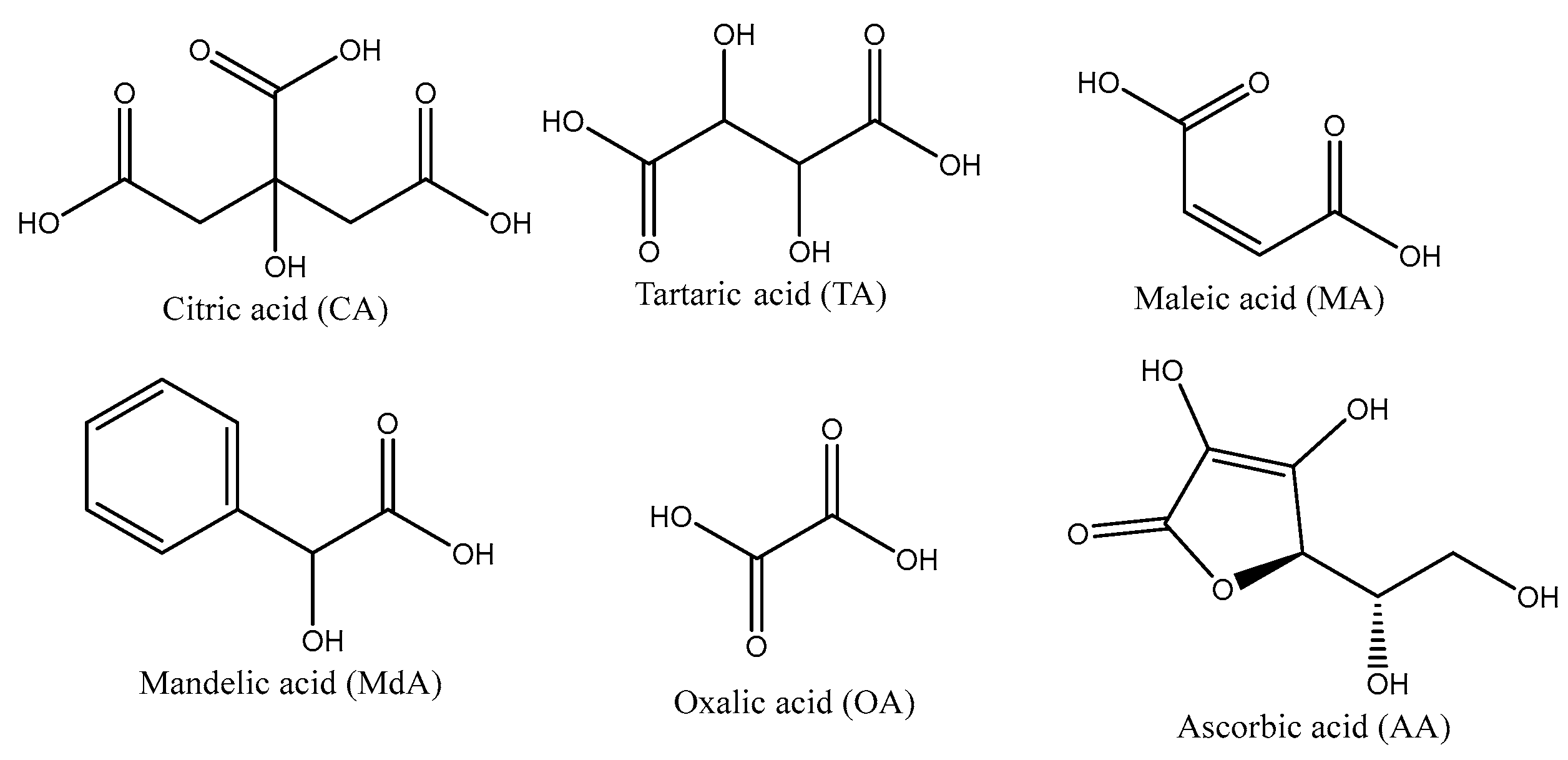

3.1.3. Type of Acid

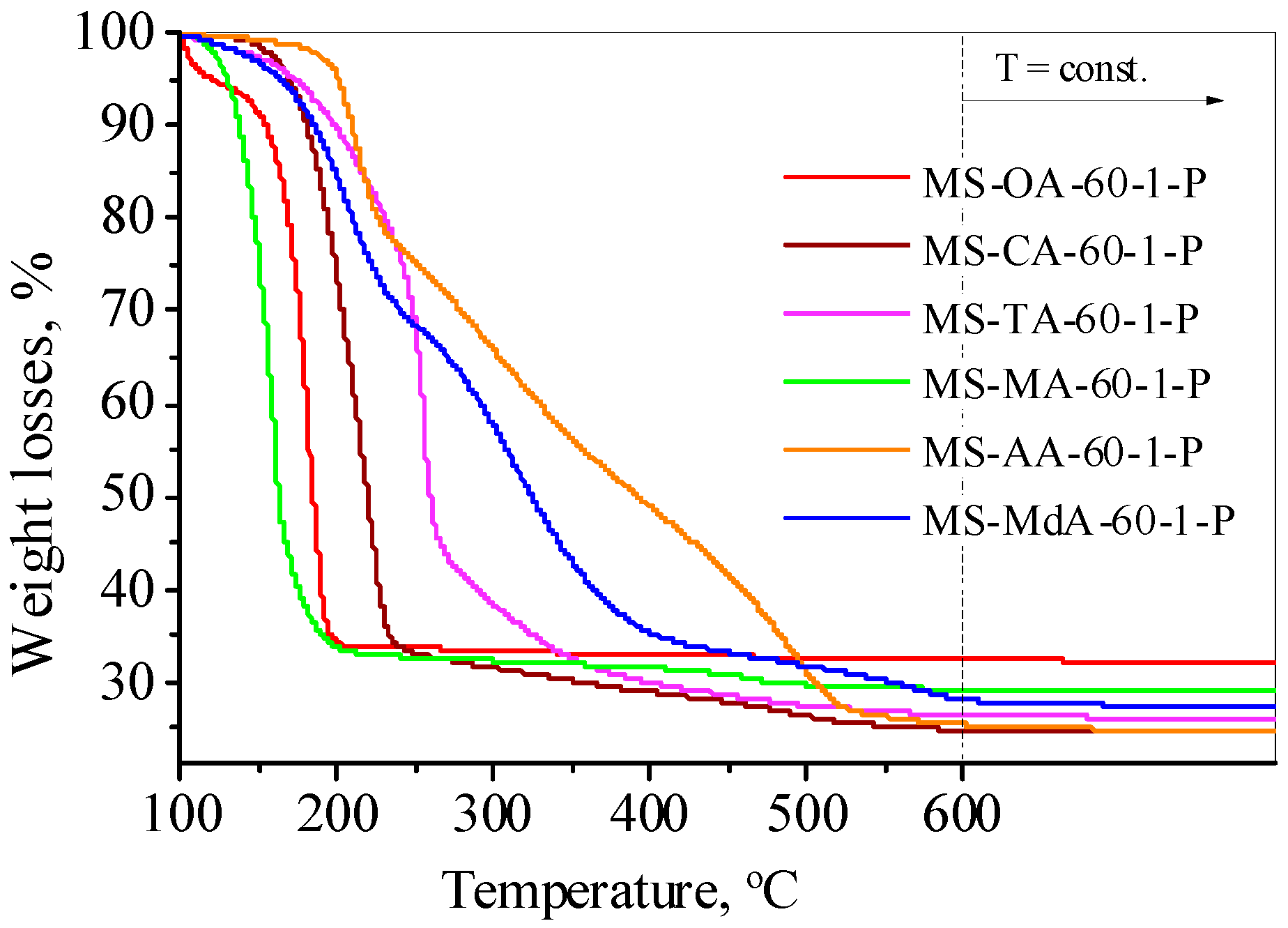

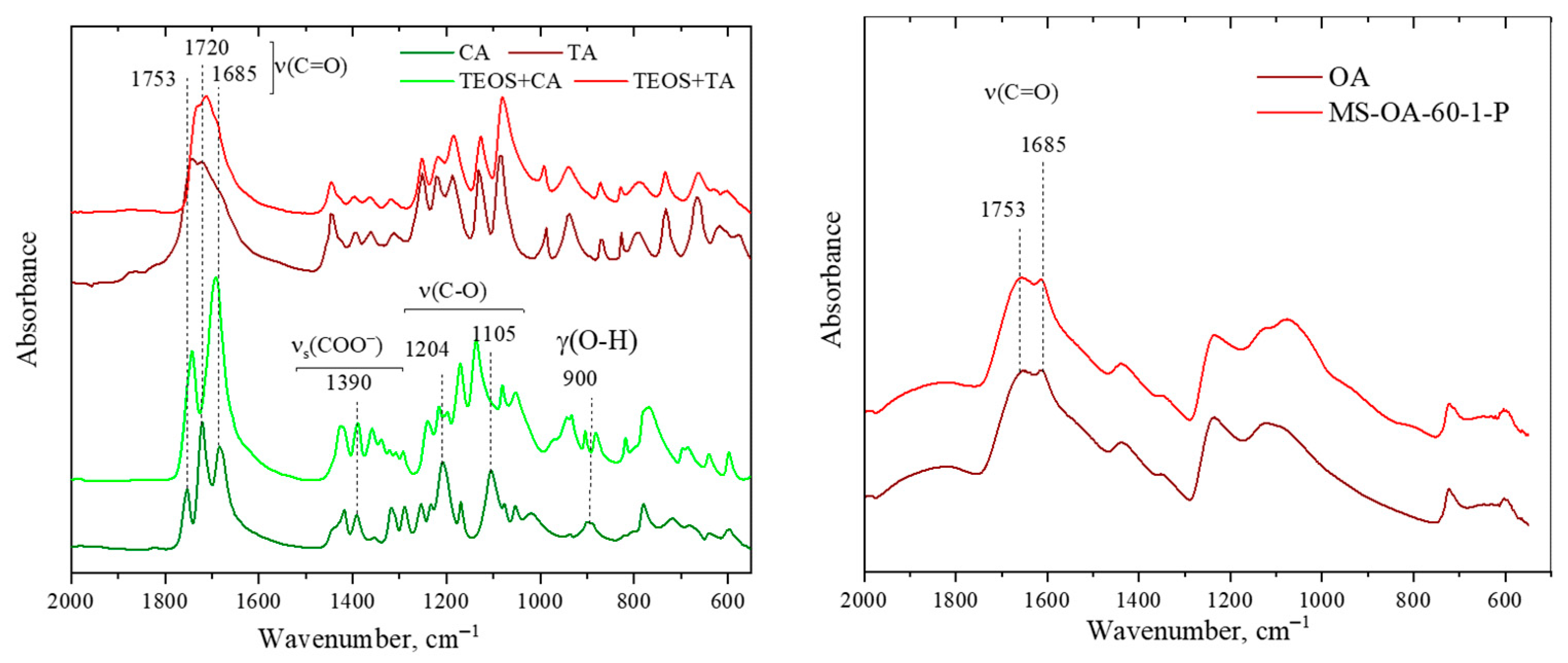

3.1.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis and FTIR Spectra

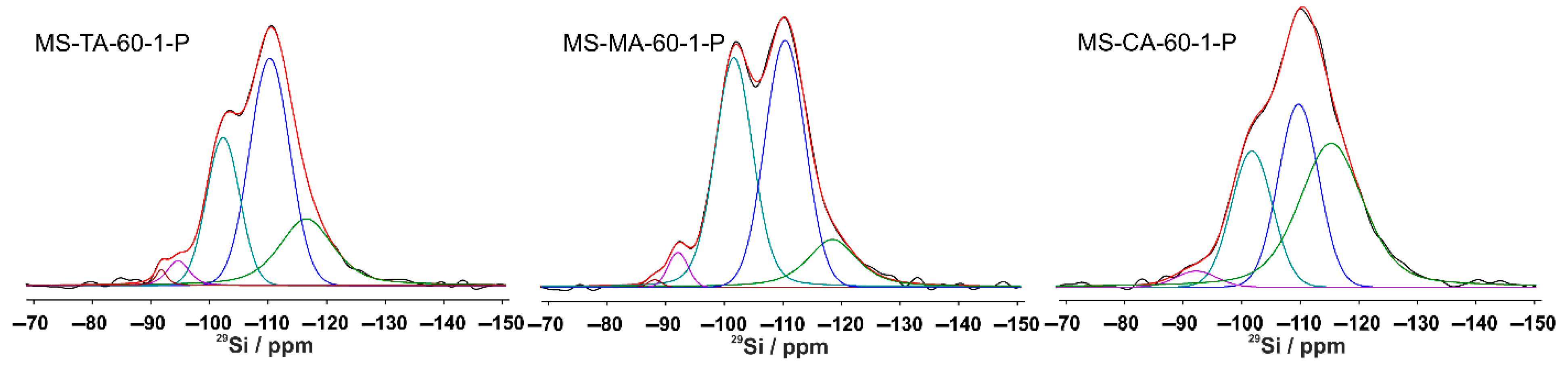

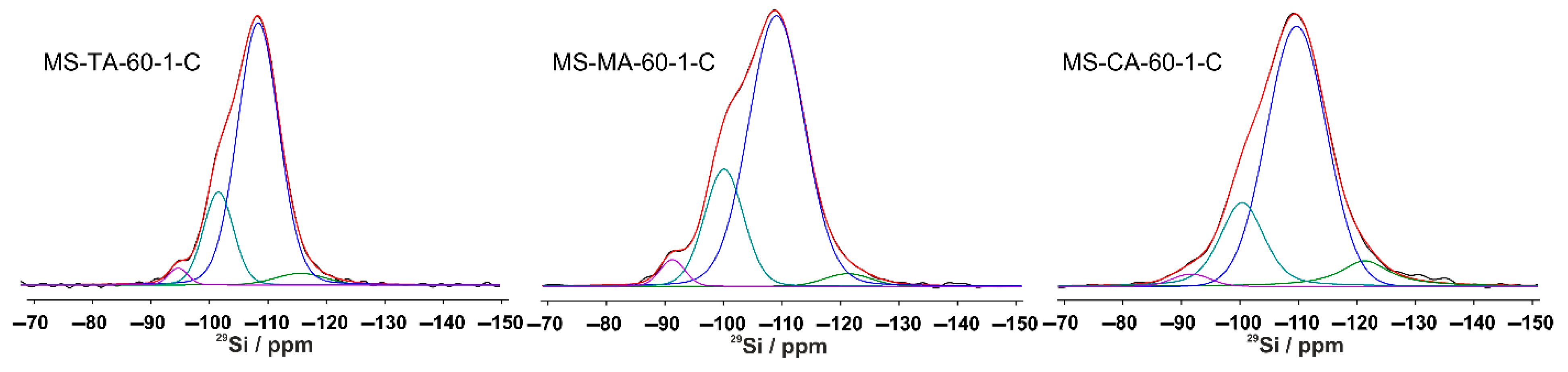

3.1.5. Solid State NMR Investigation of Silica Xerogels

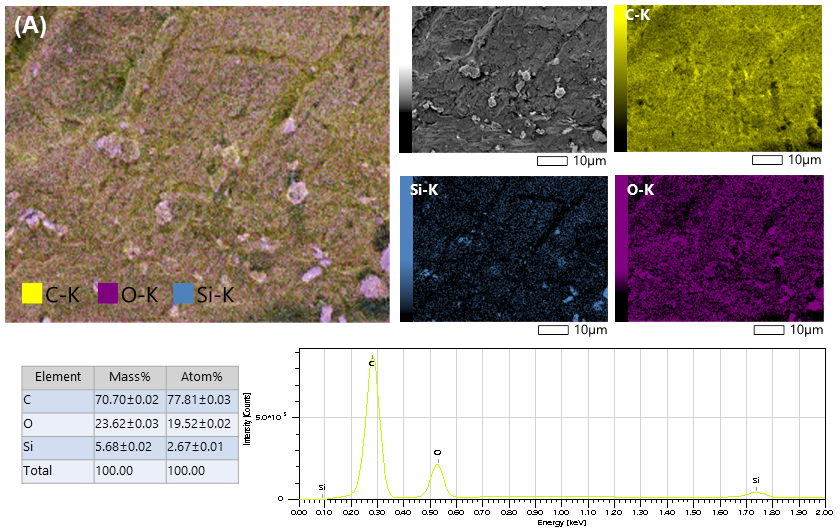

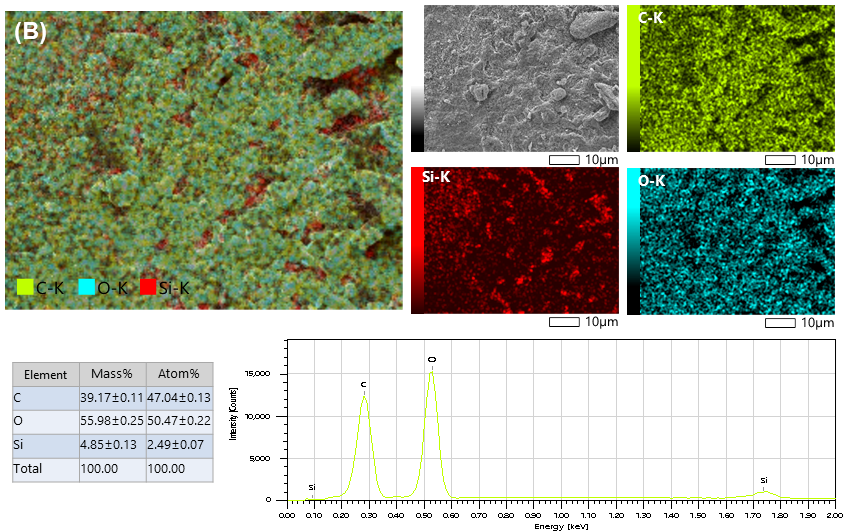

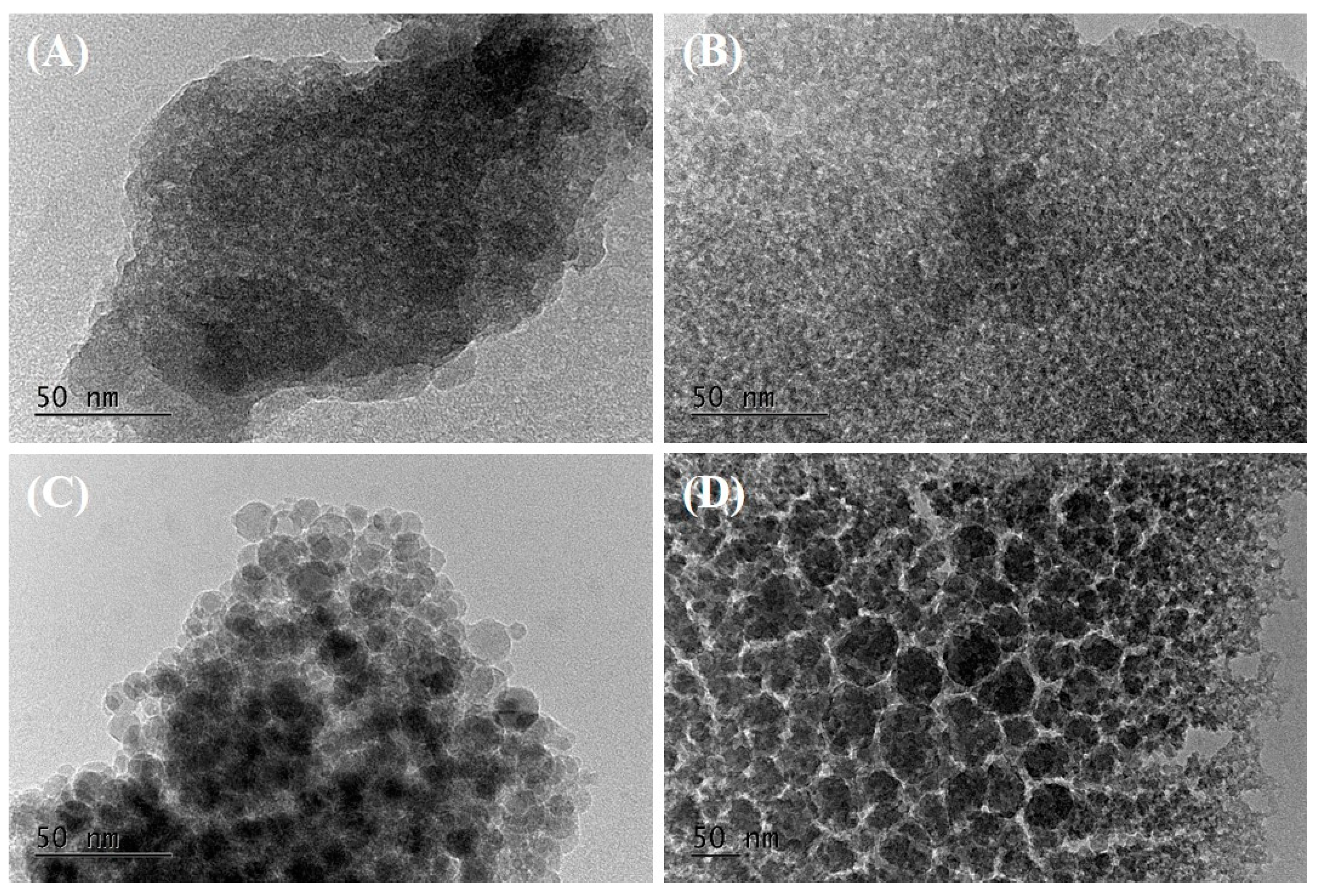

3.1.6. Morphology of Silica Xerogels Prepared by Carboxylic Acids

3.1.7. Optimization of the Template Removal Procedure

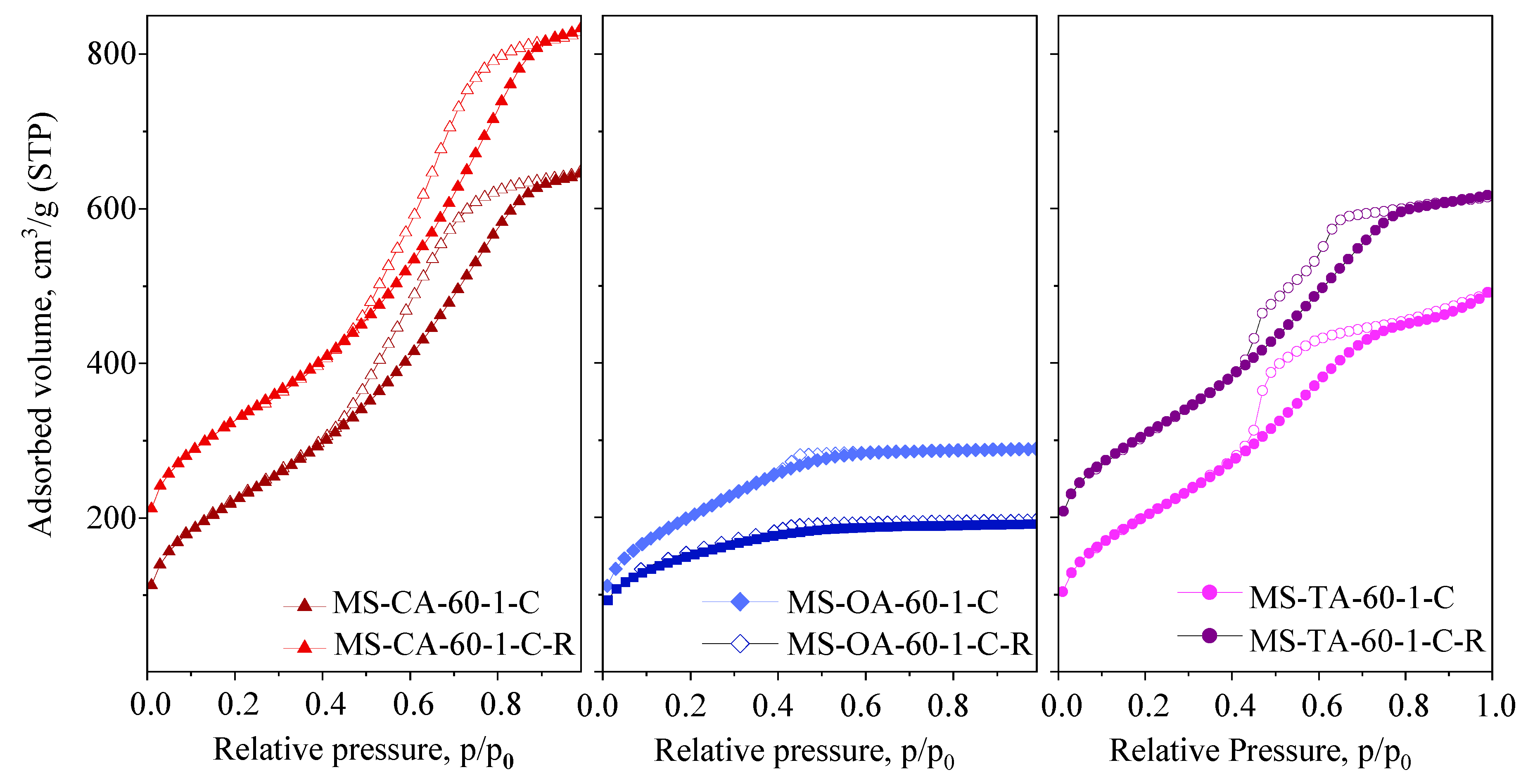

3.1.8. Regeneration of the Organic Acids

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pierre, A.C.; Pajonk, G.M. Chemistry of Aerogels and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4243–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, C.J.; Scherer, G.W. Sol–Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol–Gel Processing; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani Dorcheh, A.; Abbasi, M.H. Silica Aerogel; Synthesis, Properties and Characterization. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 199, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, J.; Huo, Q.; Melosh, N.; Fredrickson, G.H.; Chmelka, B.F.; Stucky, G.D. Stucky Triblock Copolymer Syntheses of Mesoporous Silica with Periodic 50 to 300 Angstrom Pores. Science 1998, 279, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Christopher Orilall, M.; Warren, S.C.; Kamperman, M.; DiSalvo, F.J.; Wiesner, U. Direct Access to Thermally Stable and Highly Crystalline Mesoporous Transition-Metal Oxides with Uniform Pores. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Mishra, S.B. Sol–Gel Derived Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Materials: Synthesis, Characterizations and Applications. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2011, 59, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iler, R.K. The Chemistry of Silica: Solubility, Polymerization, Colloid and Surface Properties, and Biochemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Naz, H.; Ali, R.N.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Xiang, B.; Cui, X. Fast Synthesis of Transparent and Hydrophobic Silica Aerogels Using Polyethoxydisiloxane and Methyltrimethoxysilane in One-Step Drying Process. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 45101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, A.; Schüth, F.; Huo, Q.; Kumar, D.; Margolese, D.; Maxwell, R.S.; Stucky, G.D.; Krishnamurty, M.; Petroff, P.; Firouzi, A.; et al. Cooperative Formation of Inorganic-Organic Interfaces in the Synthesis of Silicate Mesostructures. Science 1993, 261, 1299–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dash, P.; Thirumurugan, S.; Chen, Y.-L.; Dhawan, U.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-P.; Liu, W.-C.; Tseng, C.-L.; Chung, R.-J. Development of Iron Oxide Based-Upconversion Nanocomposites for Cancer Therapeutics Treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 675, 125545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleitz, F.; Schmidt, W.; Schüth, F. Calcination Behavior of Different Surfactant-Templated Mesostructured Silica Materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 65, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losurdo, M.; Giangregorio, M.M.; Bruno, G.; Poli, F.; Armelao, L.; Tondello, E. Porosity of Mesoporous Silica Thin Films: Kinetics of the Template Removal Process by Ellipsometry. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 126, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérardin, C.; Reboul, J.; Bonne, M.; Lebeau, B. Ecodesign of Ordered Mesoporous Silica Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4217–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Jin, D.; Ding, T.; Shih, W.-H.; Liu, X.; Cheng, S.Z.D.; Fu, Q. A Non-Surfactant Templating Route to Mesoporous Silica Materials. Adv. Mater. 1998, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapathy, U.; Proctor, A.; Shultz, J. A Simple Method for Production of Pure Silica from Rice Hull Ash. Bioresour. Technol. 2000, 73, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandaker, T.; Islam, T.; Nandi, A.; Anik, M.A.A.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Hasan, M.K.; Hossain, M.S. Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials for Sustainable Energy Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 693–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertpanyapornchai, B.; Yokoi, T.; Ngamcharussrivichai, C. Citric Acid as Complexing Agent in Synthesis of Mesoporous Strontium Titanate via Neutral-Templated Self-Assembly Sol–Gel Combustion Method. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 226, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Bhaumik, A. Soft Templating Strategies for the Synthesis of Mesoporous Materials: Inorganic, Organic–Inorganic Hybrid and Purely Organic Solids. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 189–190, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinjokun, A.I.; Ojumu, T.V.; Ogunfowokan, A.O. Biomass, Abundant Resources for Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Material. In Microporous and Mesoporous Materials; Dariani, R.S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, S.; Kang, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Low-Cost Route for Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Materials with High Silanol Groups and Their Application for Cu(II) Removal. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izutsu, H.; Mizukami, F.; Nair, P.K.; Kiyozumi, Y.; Maeda, K. Preparation and Characterization of Porous Silica Spheres by the Sol–Gel Method in the Presence of Tartaric Acid. J. Mater. Chem. 1997, 7, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Glomski, B.; R Pauly, T.; Pinnavaia, T.J. A New Nonionic Surfactant Pathway to Mesoporous Molecular Sieve Silicas with Long Range Framework Order. Chem. Commun. 1999, 18, 1803–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akti, F.; Balci, S. Silica Xerogel and Iron Doped Silica Xerogel Synthesis in Presence of Drying Control Chemical Additives. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 297, 127347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagar, N.S.; Karandikar, P.R.; Chandwadkar, A.J.; Deshpande, R.M. Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Study of Mesoporous Carbon Materials Prepared via Mesoporous Silica Using Non-Surfactant Templating Agents. J. Porous Mater. 2021, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Aguado, M.J.; Gregorkiewitz, M.; Bermejo, F.J. Structural Characterization of Silica Xerogels. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 1995, 189, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurvitsch, L. Physicochemical attractive force. J. Phys. Chem. Soc. Russ. 1915, 47, 805–827. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinker, C.J.; Scherer, G.W. CHAPTER 2—Hydrolysis and Condensation I: Nonsilicates; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 20–95. ISBN 978-0-08-057103-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.B.; Qiu, K.Y.; Wei, Y. Preparation of Mesoporous Silica Materials with Non-Surfactant Hydroxy-Carboxylic Acid Compounds as Templates via Sol–Gel Process. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2001, 283, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L.; West, J.K. The Sol-Gel Process. Chem. Rev. 1990, 90, 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Sato, S.; Sodesawa, T.; Kawakita, M.; Ogura, K. High Surface-Area Silica with Controlled Pore Size Prepared from Nanocomposite of Silica and Citric Acid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 12184–12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Sommerdijk, N. Sol-Gel Materials: Chemistry and Applications; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2002; ISBN 9056993267. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Tanha, T. Effect of PH, Acid Catalyst, and Aging Time on Pore Characteristics of Dried Silica Xerogel. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, M.; Mitova, V.; Dimitrov, M.; Rosmini, C.; Tsacheva, I.; Shestakova, P.; Karashanova, D.; Karadjova, I.; Koseva, N. Mesoporous Silica with an Alveolar Construction Obtained by Eco-Friendly Treatment of Rice Husks. Molecules 2024, 29, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, M.; Mihaylova, R.; Momekov, G.; Momekova, D.; Lazarova, H.; Trendafilova, I.; Mitova, V.; Koseva, N.; Mihályi, J.; Shestakova, P.; et al. Verapamil Delivery Systems on the Basis of Mesoporous ZSM-5/KIT-6 and ZSM-5/SBA-15 Polymer Nanocomposites as a Potential Tool to Overcome MDR in Cancer Cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 142, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szegedi, Á.; Shestakova, P.; Trendafilova, I.; Mihayi, J.; Tsacheva, I.; Mitova, V.; Kyulavska, M.; Koseva, N.; Momekova, D.; Konstantinov, S.; et al. Modified Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Coated by Polymer Complex as Novel Curcumin Delivery Carriers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 49, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, I.; Szegedi, Á.; Yoncheva, K.; Shestakova, P.; Mihály, J.; Ristić, A.; Konstantinov, S.; Popova, M. A PH Dependent Delivery of Mesalazine from Polymer Coated and Drug-Loaded SBA-16 Systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 81, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Samples | SSA m2/g | Vtot cm3/g | SAmes m2/g | Vmeso cm3/g | PD nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-CA-30-3-C | 763 | 1.08 | 763 | 1.08 | - |

| MS-CA-60-3-C | 681 | 1.01 | 681 | 1.01 | 3.9/6.7 |

| MS-CA-90-3-C | 601 | 1.17 | 601 | 1.17 | 4.6/8.6 |

| MS-OA-30-3-C | 696 | 0.50 | 696 | 0.50 | - |

| MS-OA-60-3-C | 705 | 0.53 | 687 | 0.53 | - |

| MS-OA-90-3-C | 753 | 0.67 | 753 | 0.67 | - |

| MS-TA-30-3-C | 782 | 0.82 | 782 | 0.82 | - |

| MS-TA-60-3-C | 692 | 0.96 | 692 | 0.96 | 4.6 |

| MS-TA-90-3-C | 667 | 1.12 | 667 | 1.12 | 5.6 |

| Samples | SSA m2/g | Vtot cm3/g | SAmes m2/g | Vmeso cm3/g | PD nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-CA-60-1-C | 814 | 1.00 | 814 | 1.00 | 3.9/5.4 |

| MS-CA-60-3-C | 681 | 1.23 | 681 | 1.23 | 3.9/6.7 |

| MS-OA-60-1-C | 730 | 0.45 | 730 | 0.45 | 2.5 |

| MS-OA-60-3-C | 705 | 0.53 | 705 | 0.53 | - |

| MS-TA-60-1-C | 738 | 0.76 | 738 | 0.76 | - |

| MS-TA-60-3-C | 692 | 0.96 | 692 | 0.96 | 4.6 |

| Samples | SSA m2/g | Vtot cm3/g | SAmes m2/g | Vmic cm3/g | Vmeso cm3/g | PD nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-CA-60-1-C | 814 | 1.00 | 814 | - | 1.00 | 3.9/5.4 |

| MS-OA-60-1-C | 727 | 0.45 | 727 | - | 0.45 | 2.5 |

| MS-AA-60-1-C | 504 | 0.24 | - | 0.24 | 0.00 | - |

| MS-MA-60-1-C | 923 | 0.52 | 857 | 0.02 | 0.50 | 3.1 |

| MS-TA-60-1-C | 738 | 0.76 | 738 | - | 0.76 | - |

| MS-MdA-60-1-C | 802 | 0.43 | 627 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 3.2 |

| MS-TEOS-60 | 422 | 0.69 | 422 | - | 0.00 | 7.9 |

| MS-HNO3-60 | 781 | 0.44 | 745 | 0.01 | 0.43 | 3.1 |

| Samples | Si(3OH) % | Si(2OH) % | Si(1OH) % | Si(0OH) % | Si(0OH) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-AA-60-1-P | - | 10 | 26 | 40 | 24 |

| MS-AA-60-1-C | - | 2 | 21 | 76 | 1 |

| MS-TA-60-1-P | 1 | 4 | 25 | 47 | 23 |

| MS-TA-60-1-C | 2 | 19 | 75 | 4 | |

| MS-MA-60-1-P | 1 | 3 | 40 | 43 | 13 |

| MS-MA-60-1-C | - | 3 | 22 | 72 | 3 |

| MS-MdA-60-1-P | - | 2 | 39 | 42 | 17 |

| MS-MdA-60-1-C | - | 3 | 20 | 75 | 2 |

| MS-CA-60-1-P | - | 3 | 23 | 30 | 44 |

| MS-CA-60-1-C | - | 2 | 20 | 70 | 8 |

| MS-OA-60-1-P | - | 3 | 29 | 51 | 17 |

| MS-OA-60-1-C | - | 2 | 26 | 67 | 5 |

| Samples | SSA m2/g | Vtot cm3/g | SAmes m2/g | Vmic cm3/g | Vmeso cm3/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-CA-60-1-C | 814 | 1.00 | 814 | - | 1.00 |

| MS-CA-60-1-W | 829 | 0.62 | 829 | - | 0.62 |

| MS-OA-60-1-C | 727 | 0.45 | 706 | 0.02 | 0.43 |

| MS-OA-60-1-W | 855 | 0.56 | 822 | 0.02 | 0.54 |

| MS-TA-60-1-C | 738 | 0.76 | 738 | - | 0.76 |

| MS-TA-60-1-W | 831 | 0.86 | 831 | - | 0.86 |

| Samples | SSA m2/g | Vtot cm3/g | SAmes m2/g | Vmic cm3/g | Vmeso cm3/g | PD nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS-CA-60-1-C | 814 | 1.00 | 814 | - | 1.00 | 3.9/5.4 |

| MS-CA-60-1-C-R | 846 | 1.15 | 846 | - | 1.15 | 4.2/5.4 |

| MS-OA-60-1-C | 727 | 0.45 | 687 | 0.02 | 0.43 | - |

| MS-OA-60-1-C-R | 558 | 0.3 | 317 | 0.1 | 0.20 | - |

| MS-TA-60-1-C | 738 | 0.76 | 738 | - | 0.76 | - |

| MS-TA-60-1-C-R | 784 | 0.81 | 784 | - | 0.81 | 3.5/5.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Trendafilova, I.; Grozdanova, S.; Szegedi, Á.; Shestakova, P.; Mitrev, Y.; Ranguelov, B.; Karashanova, D.; Popova, M. Green Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Materials via a Biomass-Derived Carboxylic Acid-Assisted Approach. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010045

Trendafilova I, Grozdanova S, Szegedi Á, Shestakova P, Mitrev Y, Ranguelov B, Karashanova D, Popova M. Green Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Materials via a Biomass-Derived Carboxylic Acid-Assisted Approach. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrendafilova, Ivalina, Stela Grozdanova, Ágnes Szegedi, Pavletta Shestakova, Yavor Mitrev, Bogdan Ranguelov, Daniela Karashanova, and Margarita Popova. 2026. "Green Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Materials via a Biomass-Derived Carboxylic Acid-Assisted Approach" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010045

APA StyleTrendafilova, I., Grozdanova, S., Szegedi, Á., Shestakova, P., Mitrev, Y., Ranguelov, B., Karashanova, D., & Popova, M. (2026). Green Surfactant-Free Synthesis of Mesoporous Silica Materials via a Biomass-Derived Carboxylic Acid-Assisted Approach. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010045