Application of PVA Membrane Doped with TiO2 and ZrO2 for Higher Efficiency of Alkaline Electrolysis Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

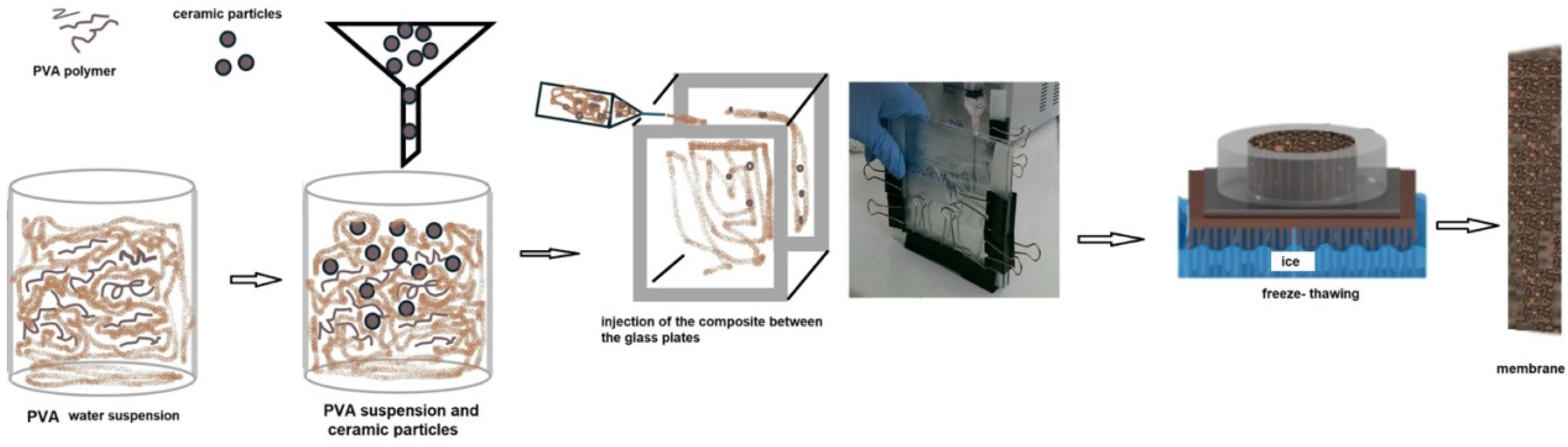

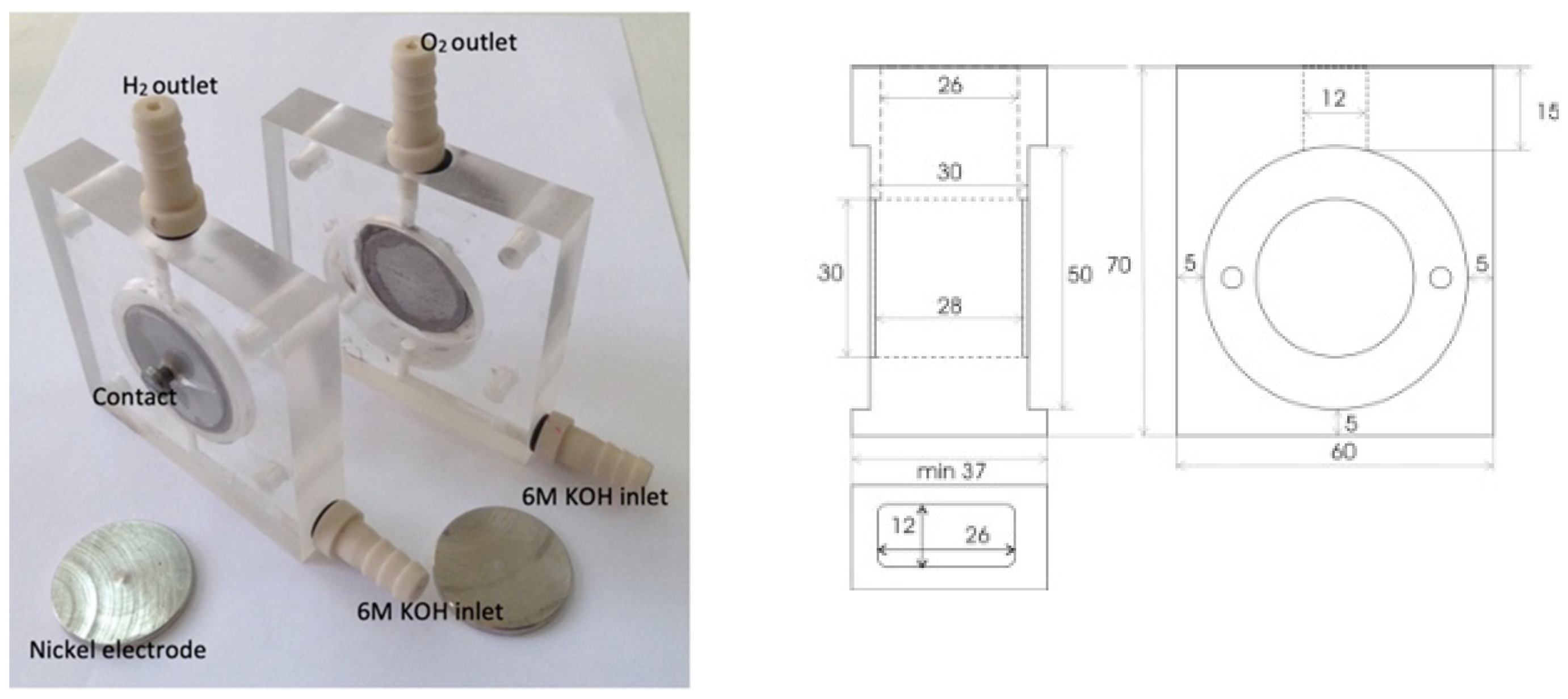

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Methods

In Situ Activation of Alkaline Electrolyzer

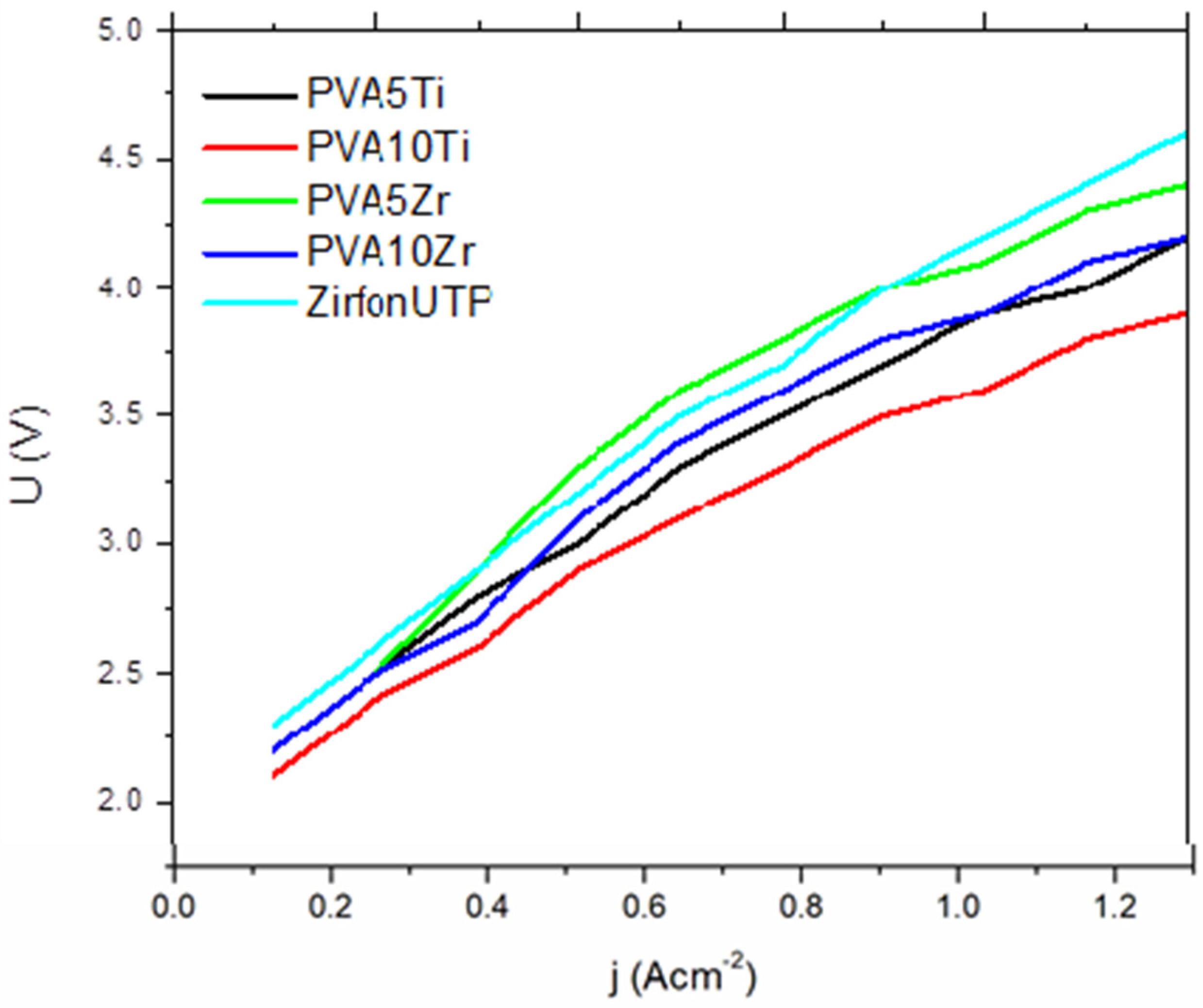

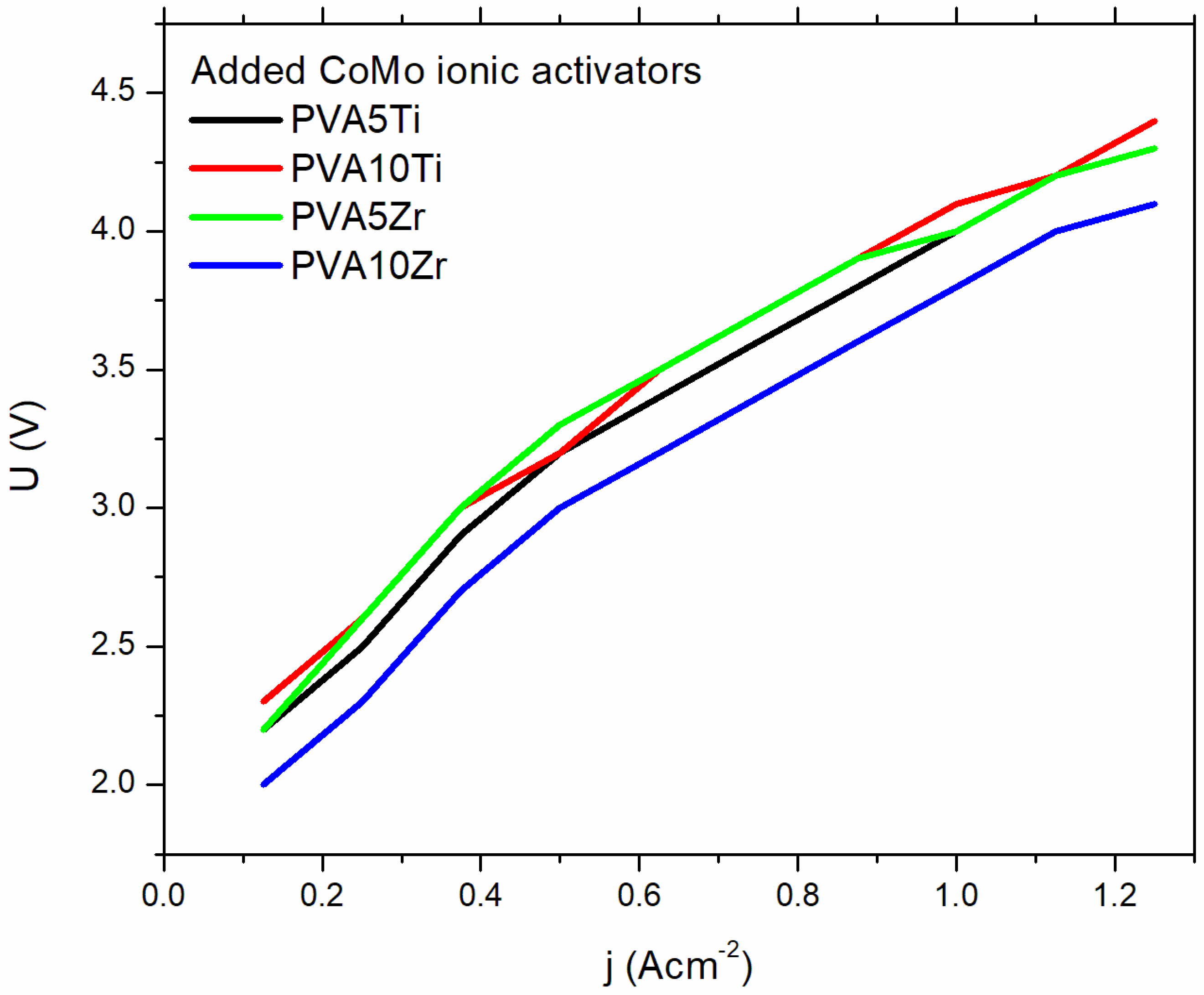

2.2. U-j Curve

2.3. Characterization

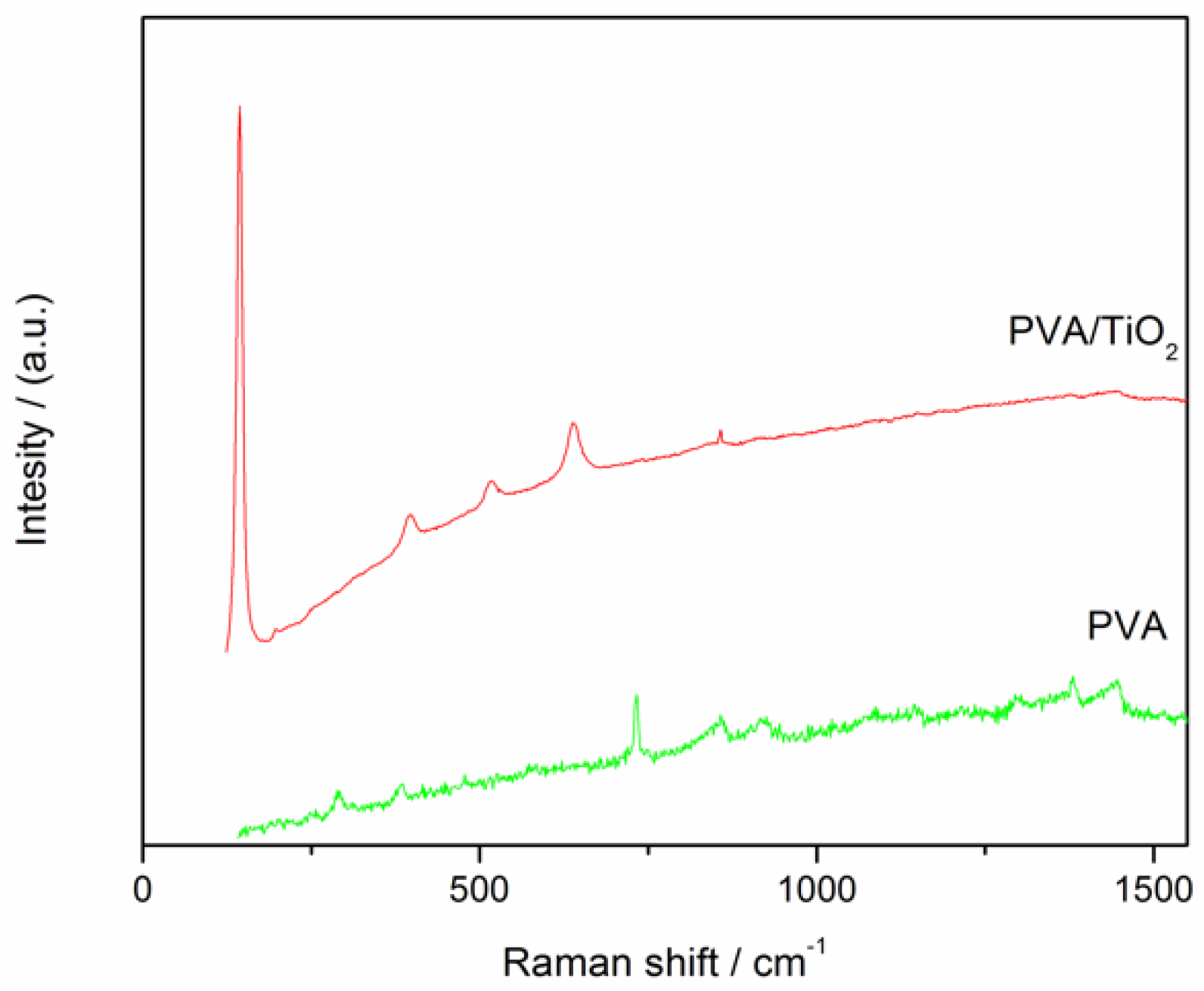

2.3.1. Raman Spectrometry

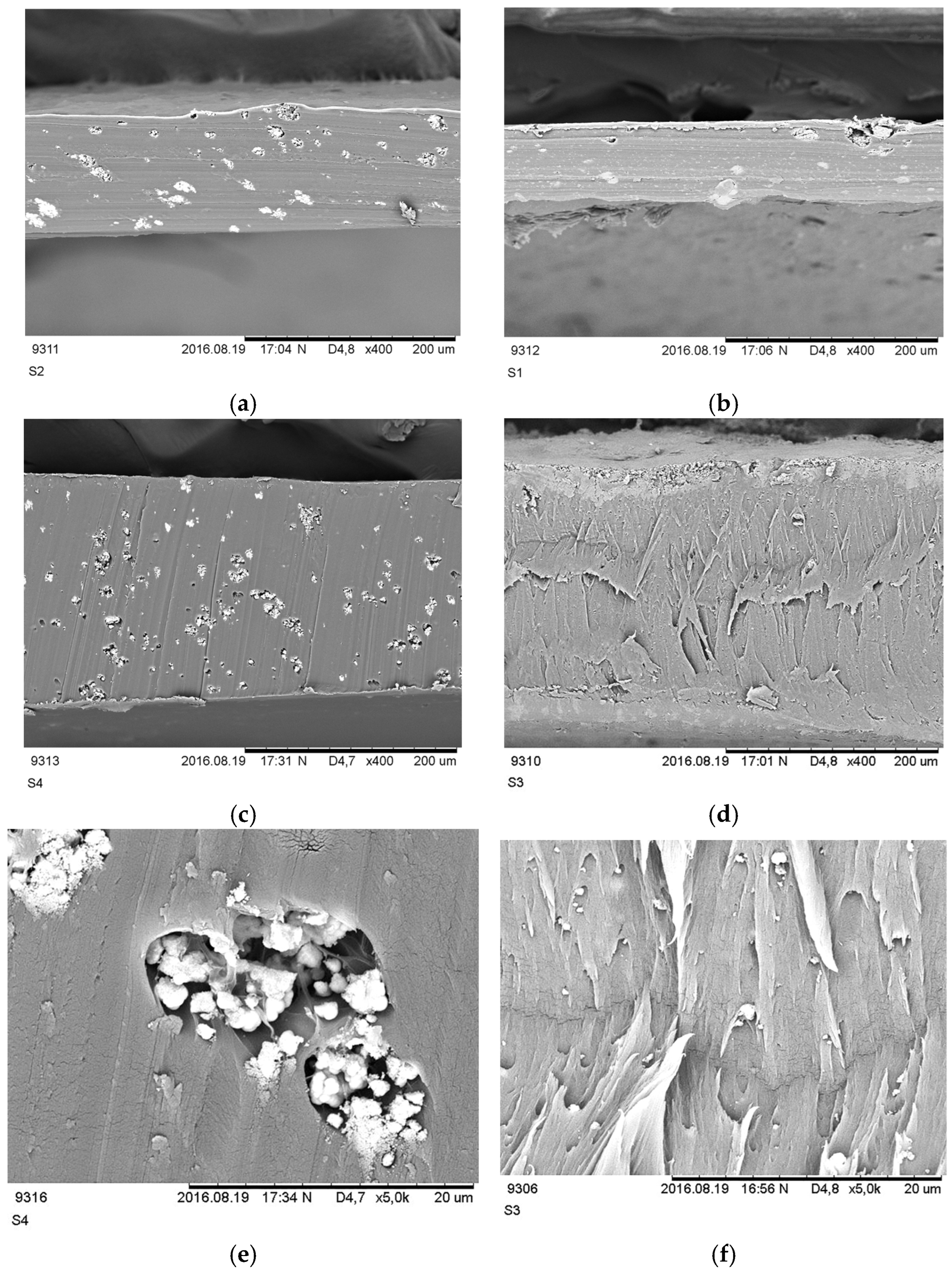

2.3.2. Morphology of Membranes

2.3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.3.4. Electrochemical Properties

2.3.5. Mechanical Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Raman Spectra

3.2. Morphology

| Membrane Samples | Maximum Load (N) | Maximum Stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| PVA-5-Ti | 17.8 | 18.4 |

| PVA-10-Ti | 18.8 | 17.4 |

| PVA-5-Zr | 10.7 | 14.6 |

| PVA-10-Zr | 33.8 | 12.4 |

| Zirfon UTP500 | 79.8 | 18.6 |

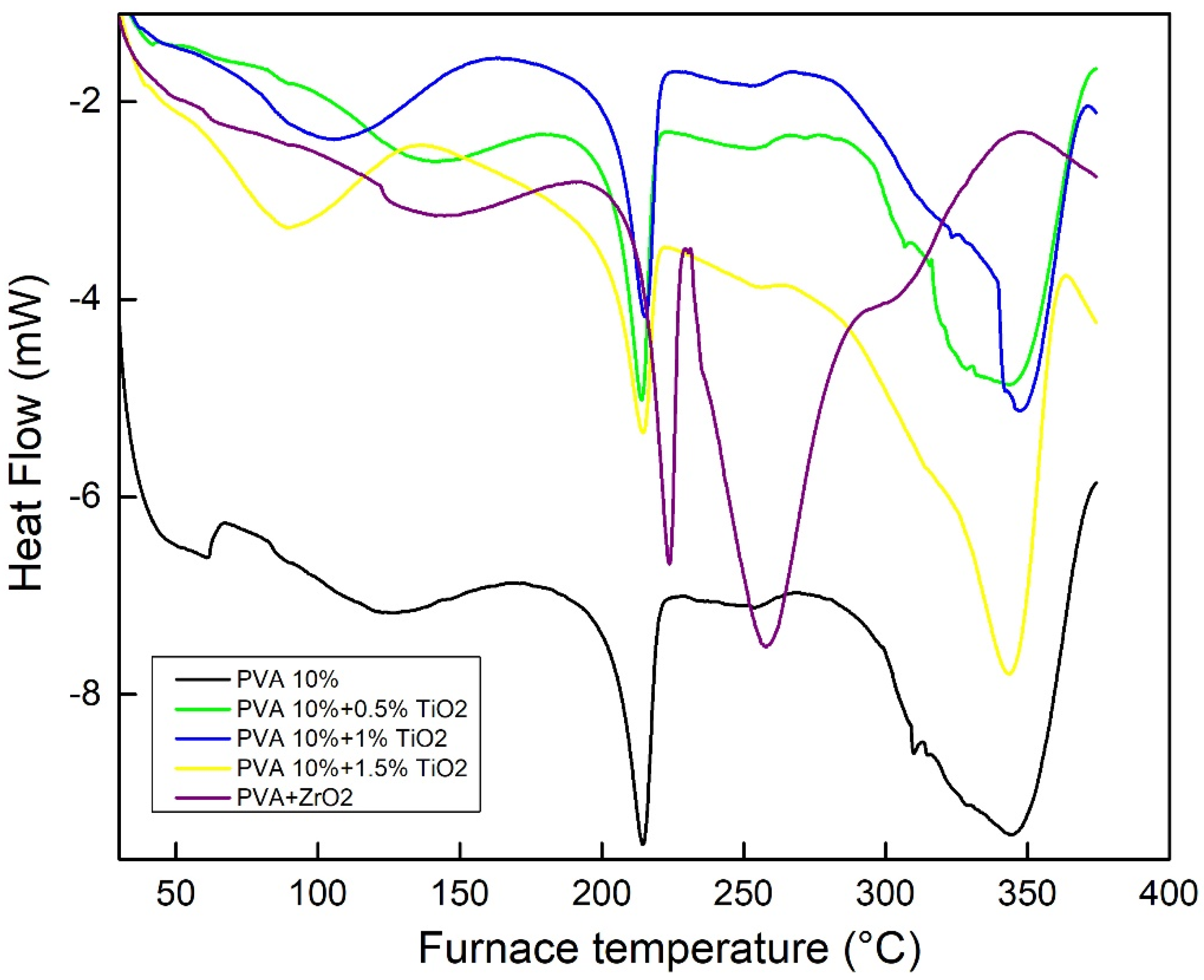

3.3. DSC Results

| Membrane Samples | Thickness (mm) | Resistance (mΩ) | Conductivity (Scm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PVA-5 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 590 | 0.014 |

| PVA-10 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 555 | 0.024 |

| PVA-5-Ti | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 240 | 0.019 |

| PVA-10-Ti | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 243 | 0.047 |

| PVA-5-Zr | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 373 | 0.015 |

| PVA-10-Zr | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 530 | 0.018 |

| Commercial membrane | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 274 | 0.059 |

3.4. Ionic Conductivity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gandia, L.M.; Arzamendi, G.; Dieguez, P.M. Renewable Hydrogen Technology: Renewable Hydrogen Technologies: Production, Purification, Storage, Applications and Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 1699–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.S.; Lim, H. An overview of water electrolysis technologies for green hydrogen production. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 13793–13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkensmeier, D.; Cho, W.-C.; Jannasch, P.; Stojadinovic, J.; Li, Q.; Aili, D.; Jensen, J.O. Separators and Membranes for Advanced Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 6393–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aili, D.; Kraglund, M.R.; Rajappan, S.C.; Serhiichuk, D.; Xia, Y.; Deimede, V.; Kallitsis, J.; Bae, C.; Jannasch, P.; Henkensmeier, D.; et al. Electrode Separators for the Next-Generation Alkaline Water Electrolyzers. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allebrod, F.; Chatzichristodoulou, C.; Mogensen, M.B. Alkaline electrolysis cell at high temperature and pressure of 250 °C and 42 bar. J. Power Sources 2013, 229, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amores, E.; Rodríguez, J.; Carreras, C. Influence of operation parameters in the modelling of alkaline water electrolysers for hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 13063–13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perović, I.; Tasić, G.; Maslovara, S.; Laušević, P.; Seović, M. Enhanced Catalytic Activity and Energy Savings with Ni-Zn-Mo Ionic Activators for Hydrogen Evolution in Alkaline Electrolysis. Materials 2023, 16, 5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslovara, S.; Vasic-Anicijevic, D.; Saponjic, A.; Djurdjevic-Milosevic, D.; Nikolic, Z.; Nikolic, V.; Marceta-Kaninski, M. Comparative analysis of in-situ ionic activators for increased energy efficiency process in alkaline electrolysers. Sci. Sinter. 2023, 57, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perović, I.; Mitrović, S.; Brković, S.; Zdolšek, N.; Seović, M.; Tasić, G.; Pašti, I. On the use of WO42− as a third component to Co–Mo ionic activator for HER in alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslovara, S.; Marceta-Kaninski, M.; Perovic, I.; Lausevic, P.; Tasic, G.; Radak, B.; Nikolic, V. Novel ternary Ni–Co–Mo based ionic activator for efficient alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 15928–15933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaninski, M.M.; Maksic, A.; Stojic, D.; Miljanic, S. Influence of Mo addition on the Ni–Co based cathodes for hydrogen evolution in alkaline water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 131, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, P.; Ismail, N.; Essalhi, M.; Tysklind, M.; Athanassiadis, D.; Tavajohi, N. Assessment of the environmental impact of polymeric membrane production. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 622, 118987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ladewig, B.P. Green synthesis of polymeric membranes: Recent advances and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sata, T.; Yamane, Y.; Matsusaki, K. Preparation and properties of anion exchange membranes having pyridinium or pyridinium derivatives as anion exchange groups. Electrochim. Acta 1999, 42, 2427–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sata, T.; Nojima, S. Transport properties of anion exchange membranes prepared by the reaction of crosslinked membranes having chloromethyl groups with 4-vinylpyridine and trimethylamine. J. Polym. Sci. Part B 1999, 37, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Baek, J.B. The promise of hydrogen production from alkaline anion exchange membrane electrolyzers. Nano Energy 2021, 87, 106162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaroddin, M.F.A.; Sabli, N.; Abdullah, T.A.T.; Siajam, S.I.; Abdullah, L.C.; Jalil, A.A.; Ahmad, A. Membrane-Based Electrolysis for Hydrogen Production: A Review. Membranes 2021, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenborre, H.; Leysen, R. On inorganic-membrane-electrolyte water electrolysis. Electrochim. Acta 1978, 23, 803–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenborre, H.; Leysen, R.; Baetsle, L. Alkaline inorganic-membrane-electrolyte (IME) water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1980, 5, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, C.T.; Colak, T.O.; Karagoz, E. A Review of the Recent Advances in Composite Membranes for Hydrogen Generation Technologies. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 23138–23154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharaman, S.; Ravichandran, S.; Davidson, D.J.; Vasudevan, S.; Sozhan, G. Polyvinyl Alcohol Based Membrane as Separator for Alkaline Water Electrolyzer. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mered, L.; Benyoucef, B.; Abadie, M.J.M.; Charles, J.P. Characterization and mechanical properties of epoxy resin reinforced with TiO₂ nanoparticles. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2011, 3, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Yuanhua, L.; Meihong, L.; Xiaowei, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Improvement of the Mechanical Properties of Nano-TiO₂/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Composites by Enhanced Interaction Between Nanofiller and Matrix. Polym. Compos 2010, 31, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, E.E.R.; Hernandez, J.H.M.; Astaiza, J.E.D. Development of a Chitosan/PVA/TiO2 Nanocomposite for Application as a Solid Polymeric Electrolyte in Fuel Cells. Polymers 2020, 12, 1691. [Google Scholar]

- Panero, S.; Fiorenza, P.; Navarra, M.A.; Romanowska, J.; Scrosati, B. Silica-added, composite poly (vinyl alcohol) membranes for fuel cell application. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, 2400–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lee, J.Z.; Hong, L. Synthesis and characterization of LiCoO₂ thin films by sol–gel method. J. Power Source 2002, 109, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.D.; Honma, I. Proton conducting organic/inorganic hybrid membranes based on poly (dimethylsiloxane) and zirconium alkoxide for high-temperature fuel cell applications. Electrochimica Acta 2003, 48, 3633–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, N.; Kurihara, Y.; Tsubota, T.; Ohno, T. Shape-Controlled Anatase Titanium (IV) Oxide Particles Prepared by Hydrothermal Treatment of Peroxo Titanic Acid in the Presence of Polyvinyl Alcohol. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 3062–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwadi, R.; Mokrani, T.; Dhlamini, M. The synthesis, characterization and electrochemical study of zirconia oxide nanoparticles for fuel cell application. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2020, 581, 411842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.H.P.; Nascimento, M.L.F.; Oliveira, H.P. Electrochemical performance of Sr-doped LaMnO₃ cathode for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Fuel Cells 2016, 16, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Xu, P.; Zhong, W.; Shen, L.; Du, Q. Transparent poly (methyl methacrylate)/silica/zirconia nanocomposites with excellent thermal stabilities. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 87, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Sang, S. Preparation of alkaline solid polymer electrolyte based on PVA-TiO2-KOH-H2O and its performance in Zn-Ni battery. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2008, 69, 2691–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Chiu, S.-J.; Lee, K.-T.; Chien, W.-C.; Lin, C.-T.; Huang, C.-A. Study of poly(vinyl alcohol)/titanium oxide composite polymer membranes and their application on alkaline direct alcohol fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2008, 184, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. Synthesis and characterization of the cross-linked PVA/TiO2 composite polymer membrane for alkaline DMFC. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 288, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Membrane Denotation | PVA (wt. %) | H2O (mL) | TiO2 (wt. %) | ZrO2 (wt. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA-5 | 5 | 95 | ||

| PVA-10 | 10 | 90 | ||

| PVA-5-Ti | 5 | 94.5 | 0.5 | |

| PVA-10-Ti | 10 | 89 | 1 | |

| PVA-5-Zr | 5 | 94.5 | 0.5 | |

| PVA-10-Zr | 10 | 89 | 1 |

| Component | Chemical Formula | Role | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) chloride | [Co(en)3]Cl3 | Ionic activator | 5 × 10−3 M |

| Sodium molybdate | Na2MoO4 | Ionic activator | 1 × 10−2 M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sladjana, M.; Dimic Misic, K.; Milovanovic, D.; Vujosevic, D.L.; Minic, A.; Nikolic, V.; Marceta Kaninski, M. Application of PVA Membrane Doped with TiO2 and ZrO2 for Higher Efficiency of Alkaline Electrolysis Process. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010027

Sladjana M, Dimic Misic K, Milovanovic D, Vujosevic DL, Minic A, Nikolic V, Marceta Kaninski M. Application of PVA Membrane Doped with TiO2 and ZrO2 for Higher Efficiency of Alkaline Electrolysis Process. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleSladjana, Maslovara, Katarina Dimic Misic, Dubravka Milovanovic, Danilo Lj Vujosevic, Andrijana Minic, Vladimir Nikolic, and Milica Marceta Kaninski. 2026. "Application of PVA Membrane Doped with TiO2 and ZrO2 for Higher Efficiency of Alkaline Electrolysis Process" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010027

APA StyleSladjana, M., Dimic Misic, K., Milovanovic, D., Vujosevic, D. L., Minic, A., Nikolic, V., & Marceta Kaninski, M. (2026). Application of PVA Membrane Doped with TiO2 and ZrO2 for Higher Efficiency of Alkaline Electrolysis Process. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010027