Structural–Material Coupling Enabling Broadband Absorption for a Graphene Aerogel All-Medium Metamaterial Absorber

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of Graphene

2.3. Synthesis of Graphene Aerogel

2.4. Characterization

2.5. Electromagnetic Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

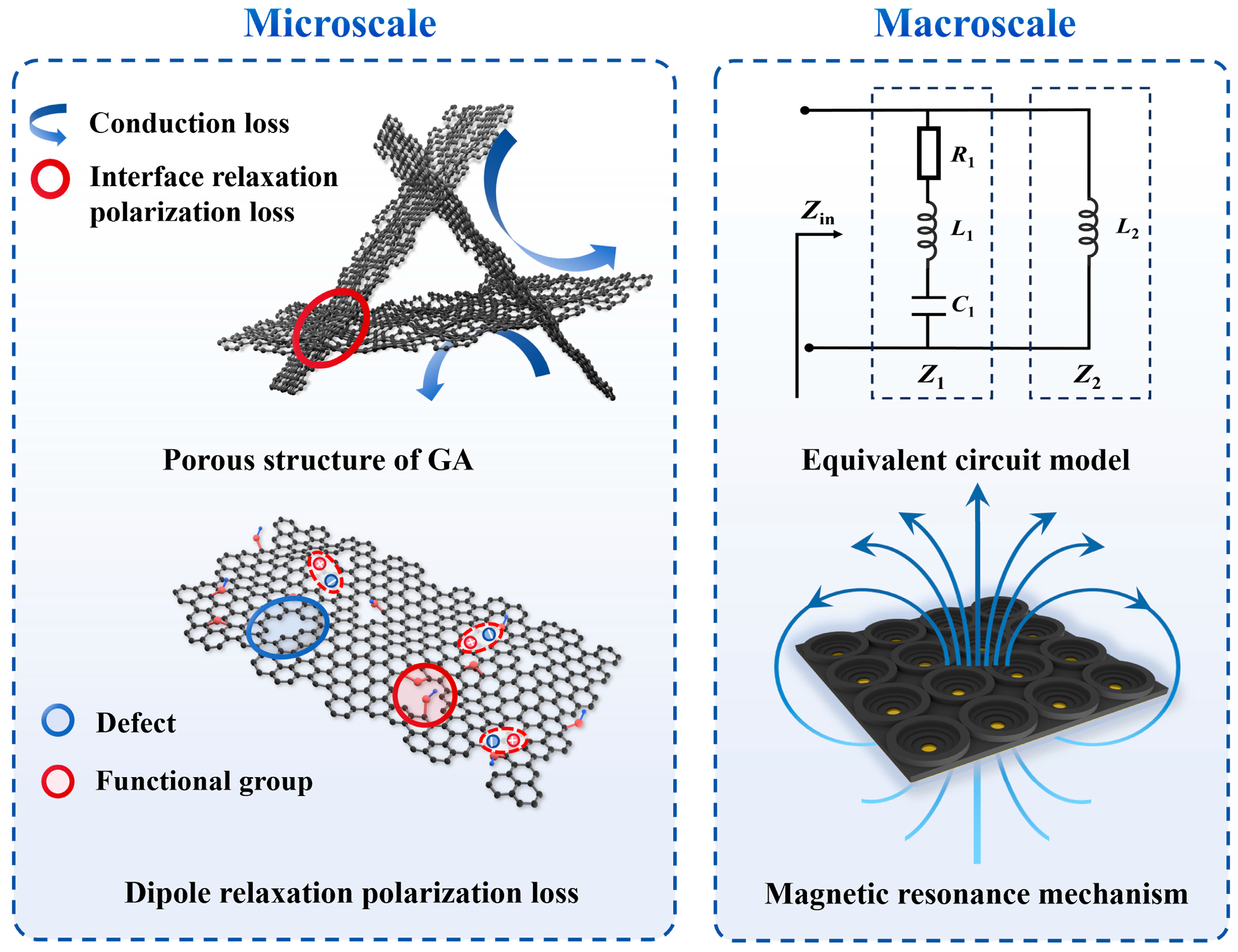

3.1. Analysis of the EMW Absorption Performance of Graphene Aerogel and Graphene

3.2. Design and Optimization of the GA-MMA

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMA | All-medium metamaterial absorber |

| GA | Graphene aerogel |

| EMW | Electromagnetic wave |

| EAB | Effective absorption bandwidth |

| GA-MMA | GA-based MMA |

| RL | Reflection loss |

References

- Cheng, J.; Li, C.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Raza, H.; Ullah, S.; Wu, J.; Zheng, G.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, D. Recent advances in design strategies and multifunctionality of flexible electromagnetic interference shielding materials. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Park, S.J.; Gu, J. Carbon-based radar absorbing materials toward stealth technologies. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chang, Q.; Chen, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, Q.; Wu, H. Mechanisms, design, and fabrication strategies for emerging electromagnetic wave-absorbing materials. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, E.; Aerts, S.; Coesoij, R.; Bhatt, C.R.; Velghe, M.; Colussi, L.; Land, D.; Petroulakis, N.; Spirito, M.; Bolte, J. A comprehensive review of 5G NR RF-EMF exposure assessment technologies: Fundamentals, advancements, challenges, niches, and implications. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xiong, Q.; Zhao, M.; Wang, B.; Dai, L.; Ni, Y. Recent advances in non-biomass and biomass-based electromagnetic shielding materials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2023, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isari, A.A.; Ghaffarkhah, A.; Hashemi, S.A.; Wuttke, S.; Arjmand, M. Structural design for EMI shielding: From underlying mechanisms to common pitfalls. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; He, M.; Zhan, B.; Guo, H.; Yang, J.-l.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, X.; Gu, J. Multifunctional microwave absorption materials: Construction strategies and functional applications. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 5874–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, D.; Hu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Jia, Z. Perspective of electromagnetic wave absorbing materials with continuously tunable effective absorption frequency bands. Compos. Commun. 2024, 50, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, M.; Xu, H.X.; Wang, X.; Huang, W. Metamaterial absorbers: From tunable surface to structural transformation. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2202509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Xu, C.; Duan, G.; Xu, W.; Pi, F. Review of broadband metamaterial absorbers: From principles, design strategies, and tunable properties to functional applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jung, K.; Choi, Y.; Hwang, S.S.; Hyun, J.K. Coupled solid and inverse antenna stacks above metal ground as metamaterial perfect electromagnetic wave absorbers with extreme subwavelength thicknesses. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liang, Z.; Shi, X.; Yang, F.; Xu, H.; Wu, Z.; Dai, R.; Smith, D.R.; Liu, Y. Long-Infrared Broadband Polarization-Sensitive Absorber with Metasurface Based on Ladder Network. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, J.; Han, X.; Qu, L.; Jin, X.; Ran, Y.; Geng, Y.; Chen, H.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, Q. Ultrawideband microwave metamaterial absorber with excellent absorption performance and high optical transparency based on double-layer mesh structures. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 4314–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Meng, X.; Zou, X.; Fang, B.; Hong, Z.; Jing, X. Terahertz wave all-dielectric broadband tunable metamaterial absorber. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 7686–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, N.I.; Sajuyigbe, S.; Mock, J.J.; Smith, D.R.; Padilla, W.J. Perfect metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 207402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, C.M.; Liu, X.; Padilla, W.J. Metamaterial electromagnetic wave absorbers. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, OP98–OP120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, K.; Ferry, V.E.; Briggs, R.M.; Atwater, H.A. Broadband polarization-independent resonant light absorption using ultrathin plasmonic super absorbers. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Qin, X.; Duan, G.; Yang, G.; Huang, W.Q.; Huang, Z. Dielectric-based metamaterials for near-perfect light absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Huang, X.; Gao, L.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Yang, H. Broadband bi-directional all-dielectric transparent metamaterial absorber. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Liu, J.; Zou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Moro, R.; Ma, L. All-dielectric Metasurfaces and Their Applications in the Terahertz Range. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2301210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

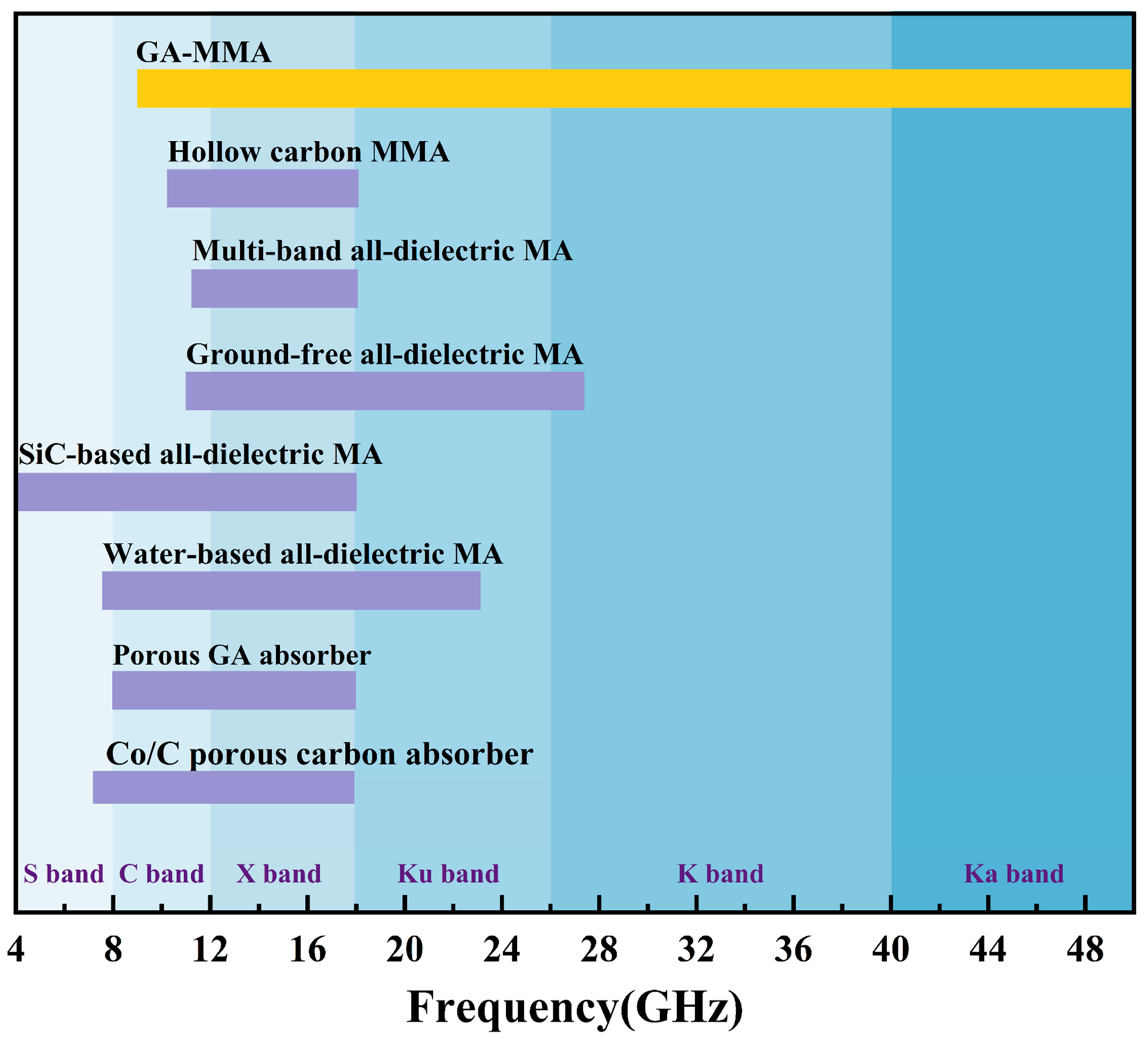

- Sui, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, K.; Guo, J.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Yun, J.; Kang, P.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, H. Breaking bandwidth limit: All-medium metamaterial absorber engineered from heterostructure-anchored N-doped hollow carbon spheres. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, T.; Xiong, Y.; Wen, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Abrahams, I.; Wang, L. A multi-band binary radar absorbing metamaterial based on a 3D low-permittivity all-dielectric structure. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 814, 152300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Quader, S.; Xiao, F.; He, C.; Liang, X.; Geng, J.; Jin, R.; Zhu, W.; Rukhlenko, I.D. Truly all-dielectric ultrabroadband metamaterial absorber: Water-based and ground-free. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2019, 18, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, C.; Lin, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. All-dielectric radar absorbing array metamaterial based on silicon carbide/carbon foam material. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 781, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, Z.; Liu, H.; Shu, X. Ultra-broadband transmission absorption of the all-dielectric water-based metamaterial. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2024, 74, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Ding, Y.; Cusano, A.; Fan, J.A.; Hu, Q.; Wang, K.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Z. Optical meta-waveguides for integrated photonics and beyond. Light Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-T.; Lin, H.; Yang, T.; Jia, B. Structured graphene metamaterial selective absorbers for high efficiency and omnidirectional solar thermal energy conversion. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, R.; Wang, C.; Xu, L.; Guan, Y.; Tian, K. Synthesis of layered double hydroxide derivative-decorated nitrogen-doped graphene composite aerogels with a unique hierarchical porous network structure for microwave absorption. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 19673–19682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Long, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Liang, G.; Zou, J.; Xie, P. Ultra-lightweight carbon nanocomposites as microwave absorber with high absorbing performance derived from flour. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Feng, Y.; Hu, X.; Su, J.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Qi, S. In situ-growth ultrathin hexagonal boron nitride/N-doped reduced graphene oxide composite aerogel for high performance of thermal insulation and electromagnetic wave absorption. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 36080–36091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, R.; Xu, J.; Shi, J. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped graphene-based binary composite aerogels for ultralightweight and broadband electromagnetic absorption. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 30214–30223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Fu, C.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Hygroscopic holey graphene aerogel fibers enable highly efficient moisture capture, heat allocation and microwave absorption. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lin, J.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Zheng, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, N. Ultralight SiO2 nanofiber-reinforced graphene aerogels for multifunctional electromagnetic wave absorber. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 61484–61494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Jiang, B.; Che, S.; Yan, L.; Li, Z.-x.; Li, Y.-f. Research progress on carbon-based materials for electromagnetic wave absorption and the related mechanisms. New Carbon Mater. 2021, 36, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Han, X.; Wang, F.; Zhao, H.; Du, Y. A review on recent advances in carbon-based dielectric system for microwave absorption. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 10782–10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Fashandi, M.; Rejeb, Z.B.; Ming, X.; Liu, Y.; Gong, P.; Li, G.; Park, C.B. Efficient electromagnetic wave absorption and thermal infrared stealth in PVTMS@ MWCNT nano-aerogel via abundant nano-sized cavities and attenuation interfaces. Nano-Micro Letters 2024, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wu, N.; Kimura, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.B.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Algadi, H.; Guo, Z.; Du, W. Initiating binary metal oxides microcubes electromagnetic wave absorber toward ultrabroad absorption bandwidth through interfacial and defects modulation. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Bi, Y.; Tong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, P.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Wu, G.; Liao, Z.; Chen, Y. Recent progress of MOF-derived porous carbon materials for microwave absorption. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 16572–16591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Murugadoss, V.; Kong, J.; He, Z.; Mai, X.; Shao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, C.; Angaiah, S. Overview of carbon nanostructures and nanocomposites for electromagnetic wave shielding. Carbon 2018, 140, 696–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunkenheimer, P.; Krohns, S.; Riegg, S.; Ebbinghaus, S.G.; Reller, A.; Loidl, A. Colossal dielectric constants in transition-metal oxides. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2009, 180, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Yun, J.; Zhao, W.; Dai, K.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. MXene-based ultrathin electromagnetic wave absorber with hydrophobicity, anticorrosion, and quantitively classified electrical losses by intercalation growth nucleation engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, T.; Cheng, J.; Cao, Q.; Zheng, G.; Liang, S.; Wang, H.; Cao, M.-S. Lightweight and high-performance microwave absorber based on 2D WS2–RGO heterostructures. Nano-Micro Lett. 2019, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xia, L. A review on metal-organic framework-derived porous carbon-based novel microwave absorption materials. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, T.; Gao, M.; Wang, P.; Pang, H.; Qiao, L.; Li, F. Strict proof and applicable range of the quarter-wavelength model for microwave absorbers. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2020, 53, 265004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, S.; Islam, M.T.; Faruque, M.R.I.; Chowdhury, M.E.; Musharavati, F. Angle-insensitive co-polarized metamaterial absorber based on equivalent circuit analysis for dual band WiFi applications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokmabadi, M.P.; Wilbert, D.S.; Kung, P.; Kim, S.M. Design and analysis of perfect terahertz metamaterial absorber by a novel dynamic circuit model. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 16455–16465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zang, Y.; Gu, J.; Han, J.; Zhang, W.; Jun Cui, T. Triple-band terahertz metamaterial absorber: Design, experiment, and physical interpretation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 154102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kim, T.; Lim, J.-S.; Chang, I.; Cho, H.H. Metamaterial-selective emitter for maximizing infrared camouflage performance with energy dissipation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21250–21257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grayli, S.V.; Patel, T.; van Kasteren, B.; Kokilathasan, S.; Tekcan, B.; Alan Tam, M.C.; Losin, W.F.; Odinotski, S.; Tsen, A.W.; Wasilewski, Z.R. Near-Unity Absorption in Semiconductor Metasurfaces Using Kerker Interference. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 9362–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| L | T1 | T2 | T3 | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.035 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, K.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, M.; Du, X.; Lu, M.; Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Yun, J. Structural–Material Coupling Enabling Broadband Absorption for a Graphene Aerogel All-Medium Metamaterial Absorber. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010018

Yan K, Ren Y, Zhang J, Song M, Du X, Lu M, Wu D, Li Y, Yun J. Structural–Material Coupling Enabling Broadband Absorption for a Graphene Aerogel All-Medium Metamaterial Absorber. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Kemeng, Yuhui Ren, Jiaxuan Zhang, Man Song, Xuhui Du, Meijiao Lu, Dingfan Wu, Yiqing Li, and Jiangni Yun. 2026. "Structural–Material Coupling Enabling Broadband Absorption for a Graphene Aerogel All-Medium Metamaterial Absorber" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010018

APA StyleYan, K., Ren, Y., Zhang, J., Song, M., Du, X., Lu, M., Wu, D., Li, Y., & Yun, J. (2026). Structural–Material Coupling Enabling Broadband Absorption for a Graphene Aerogel All-Medium Metamaterial Absorber. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010018