Functionalization of Microfiltration Media Towards Catalytic Hydrogenation of Selected Halo-Organics from Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

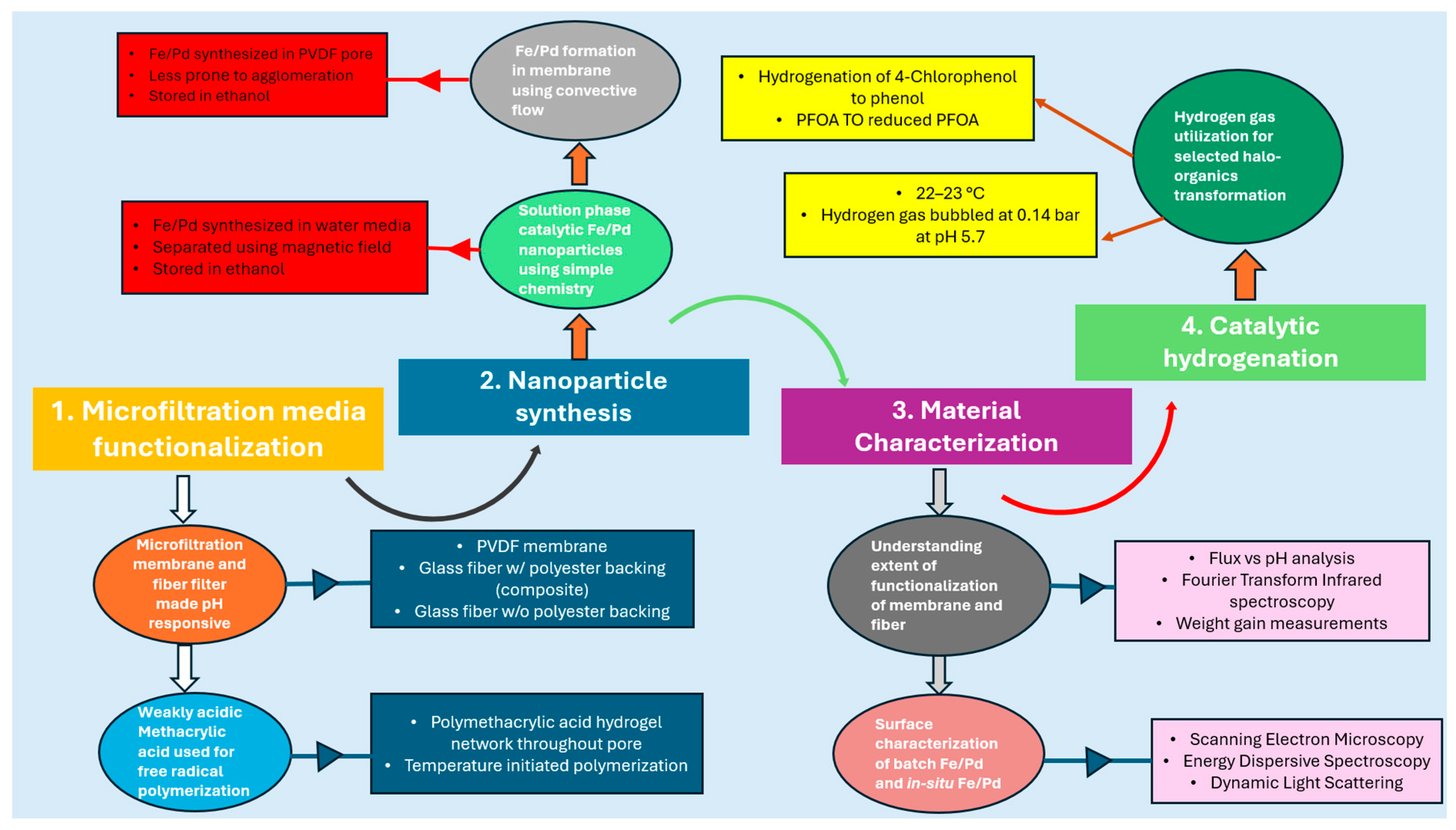

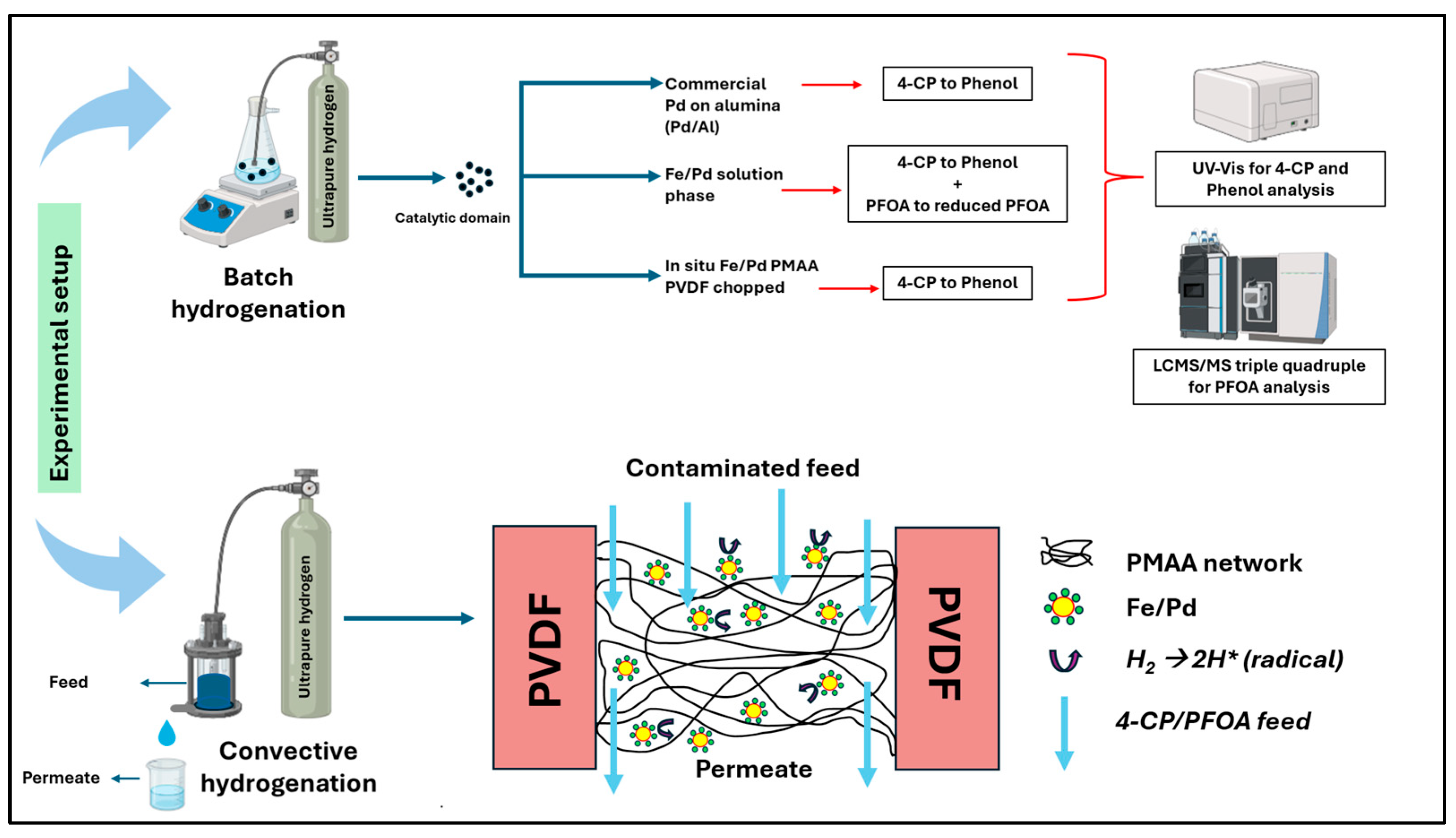

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

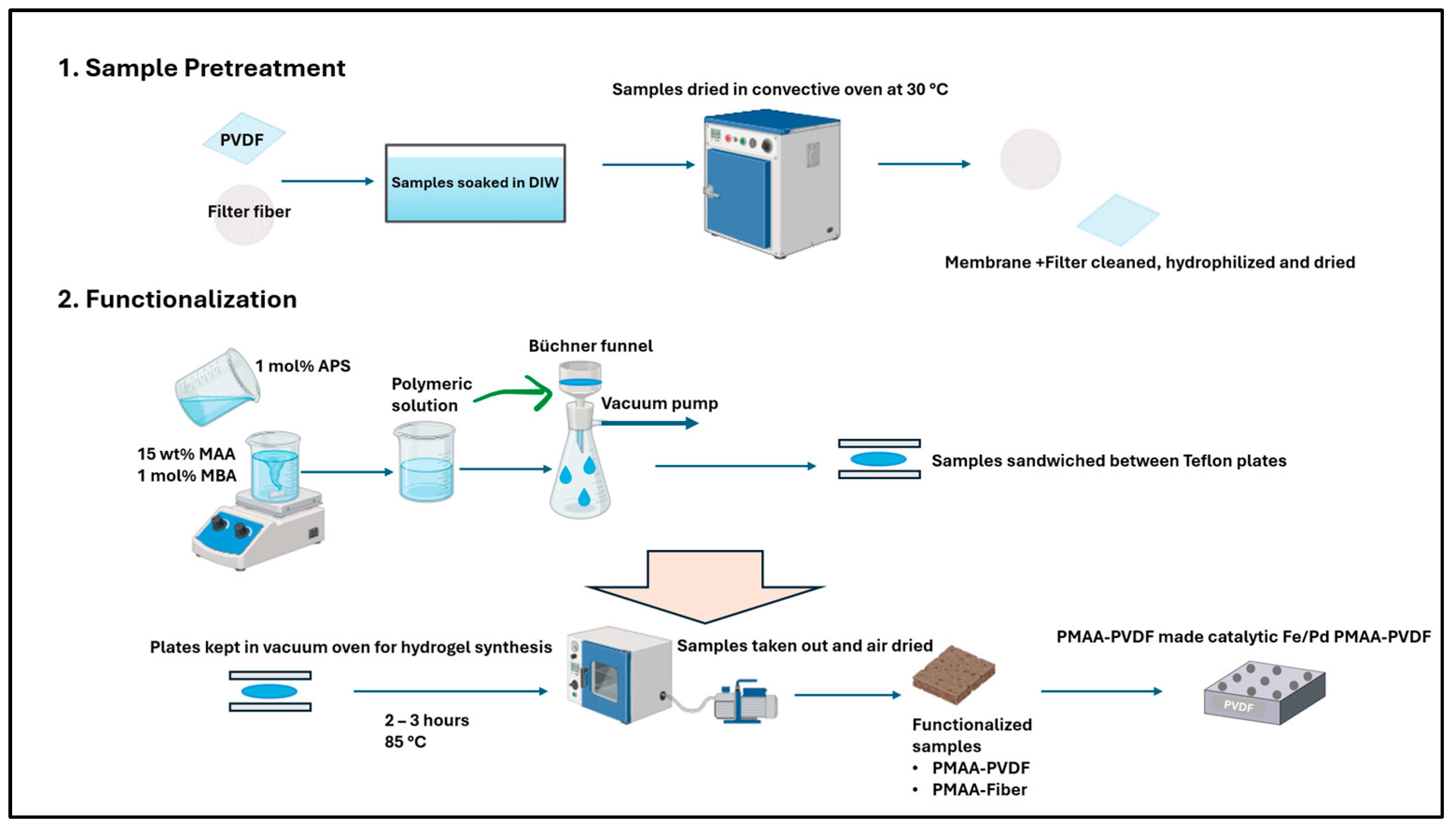

2.2. Functionalization of PVDF and Fiber Filters

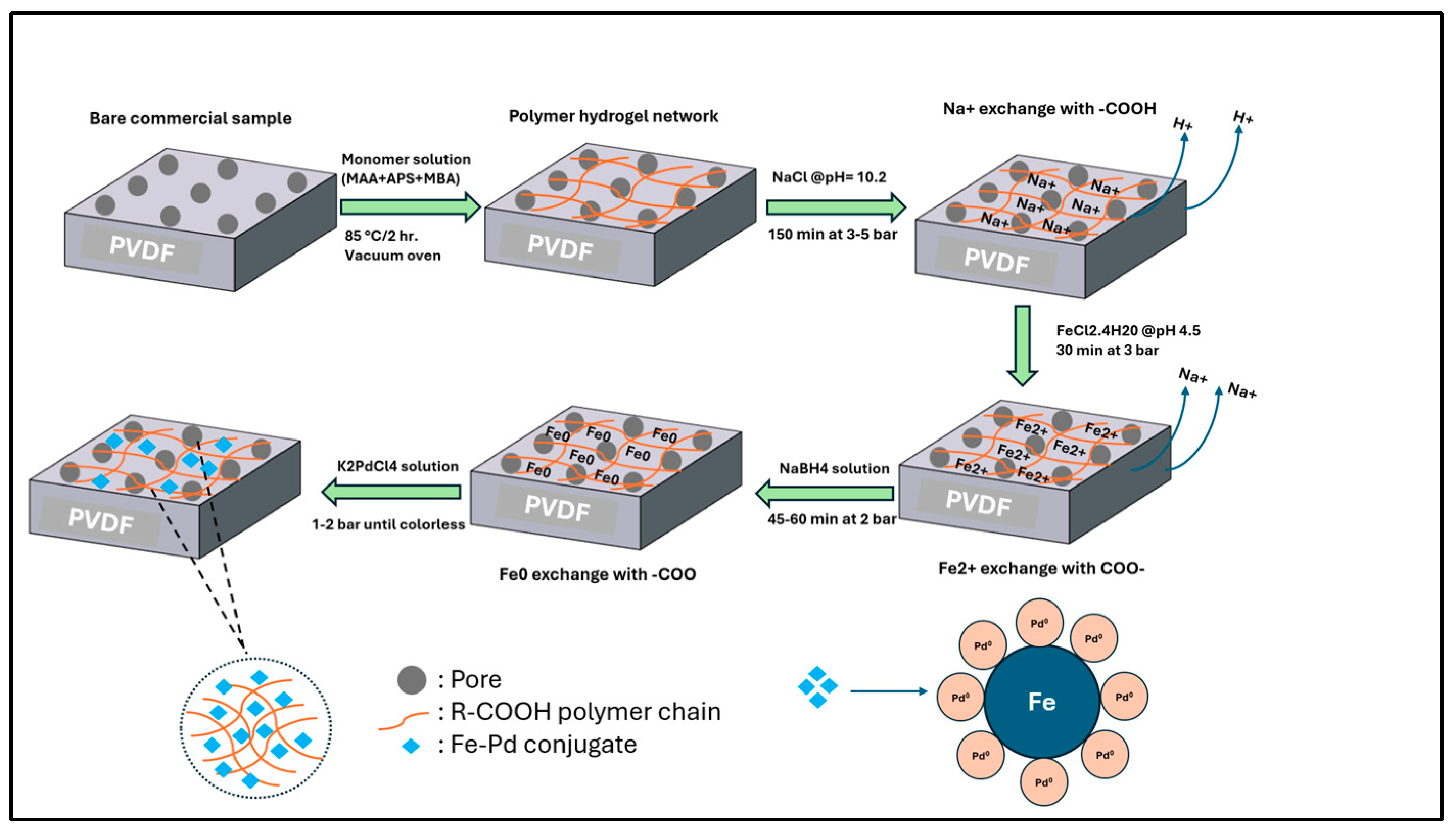

2.3. Synthesis of Fe/Pd Nanoparticles in Pore of PVDF

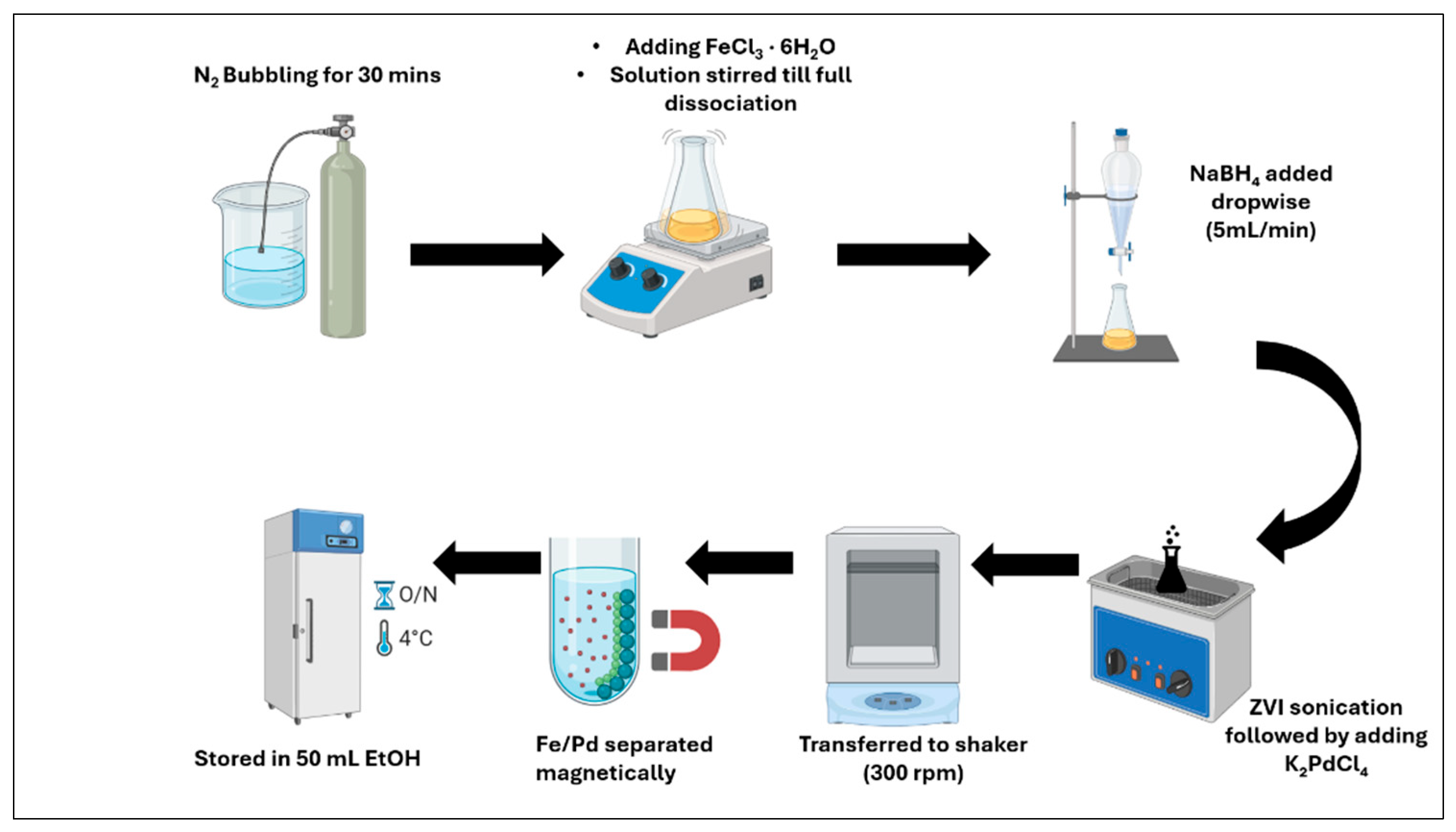

2.4. Synthesis of Fe/Pd Nanoparticles in Solution Phase

2.5. Material Characterization

2.5.1. Membrane and Filter Topography Analysis

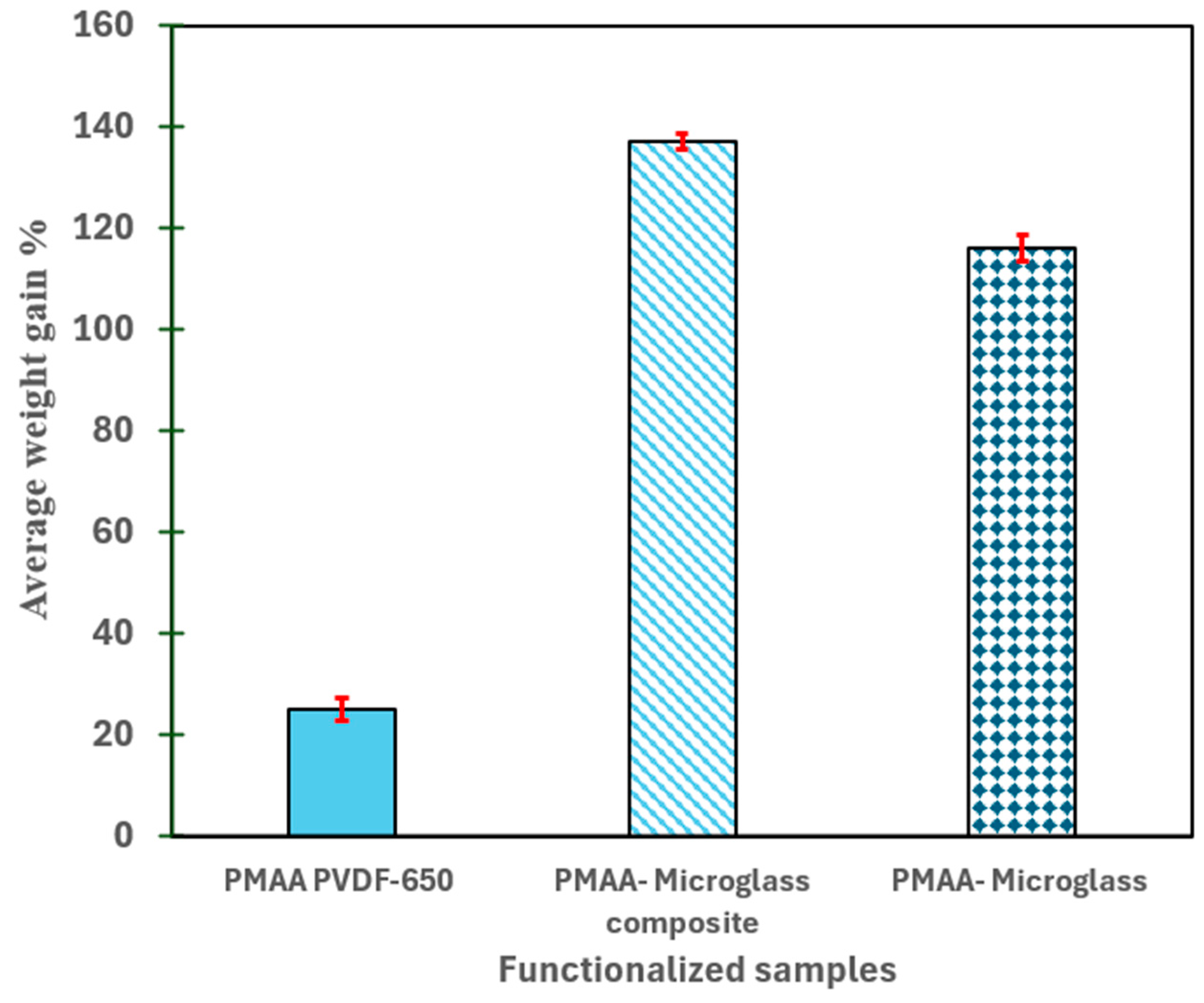

2.5.2. Weight Gain Measurements

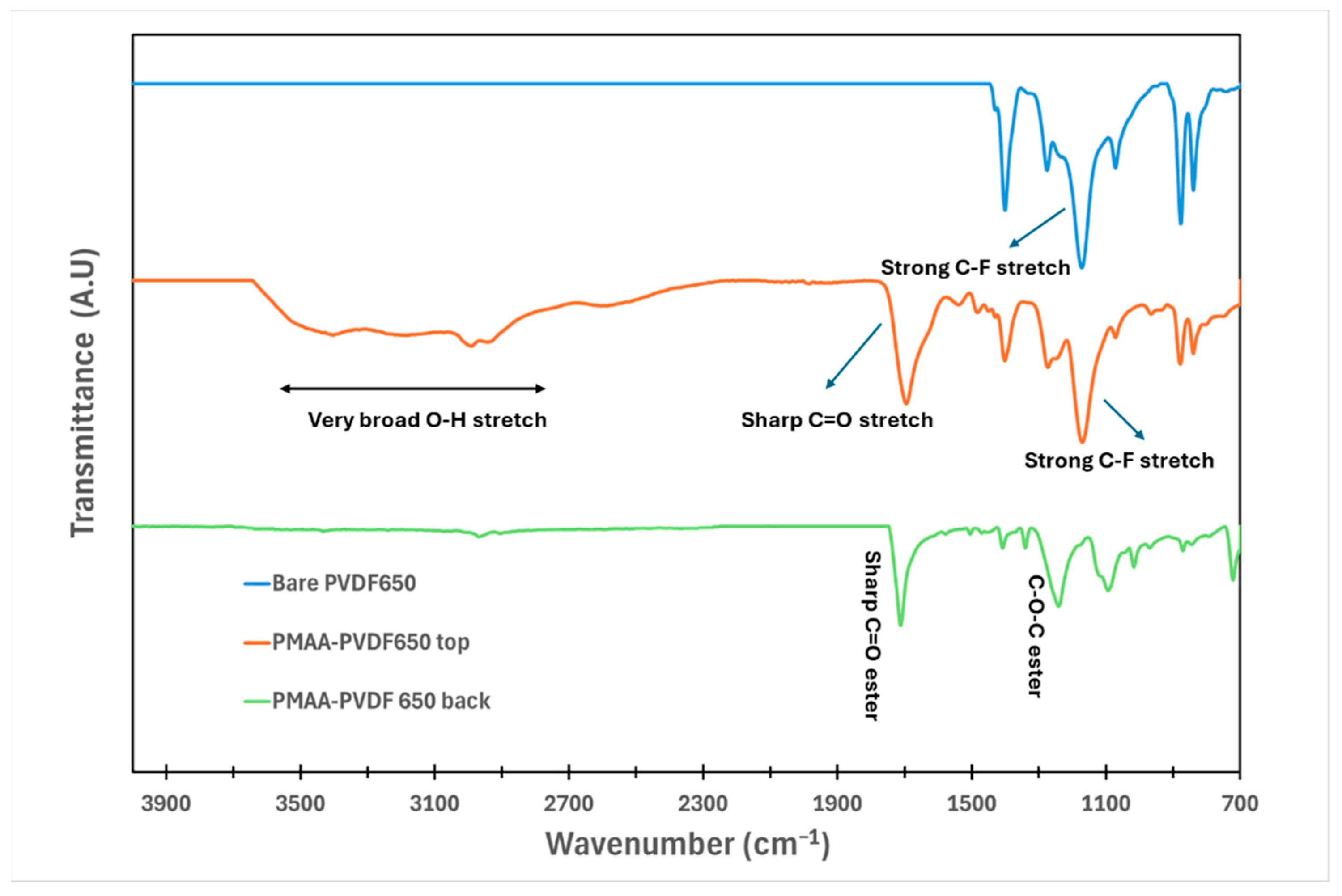

2.5.3. PMAA Incorporation onto Membranes

2.5.4. Characterization of Fe/Pd Catalytic Nanoparticles in Solution Phase

2.5.5. Morphology and Composition of Fe/Pd Nanoparticles Within the Membrane

2.6. PFOA and 4-Chlorophenol (4-CP) Hydrogenation

3. Results

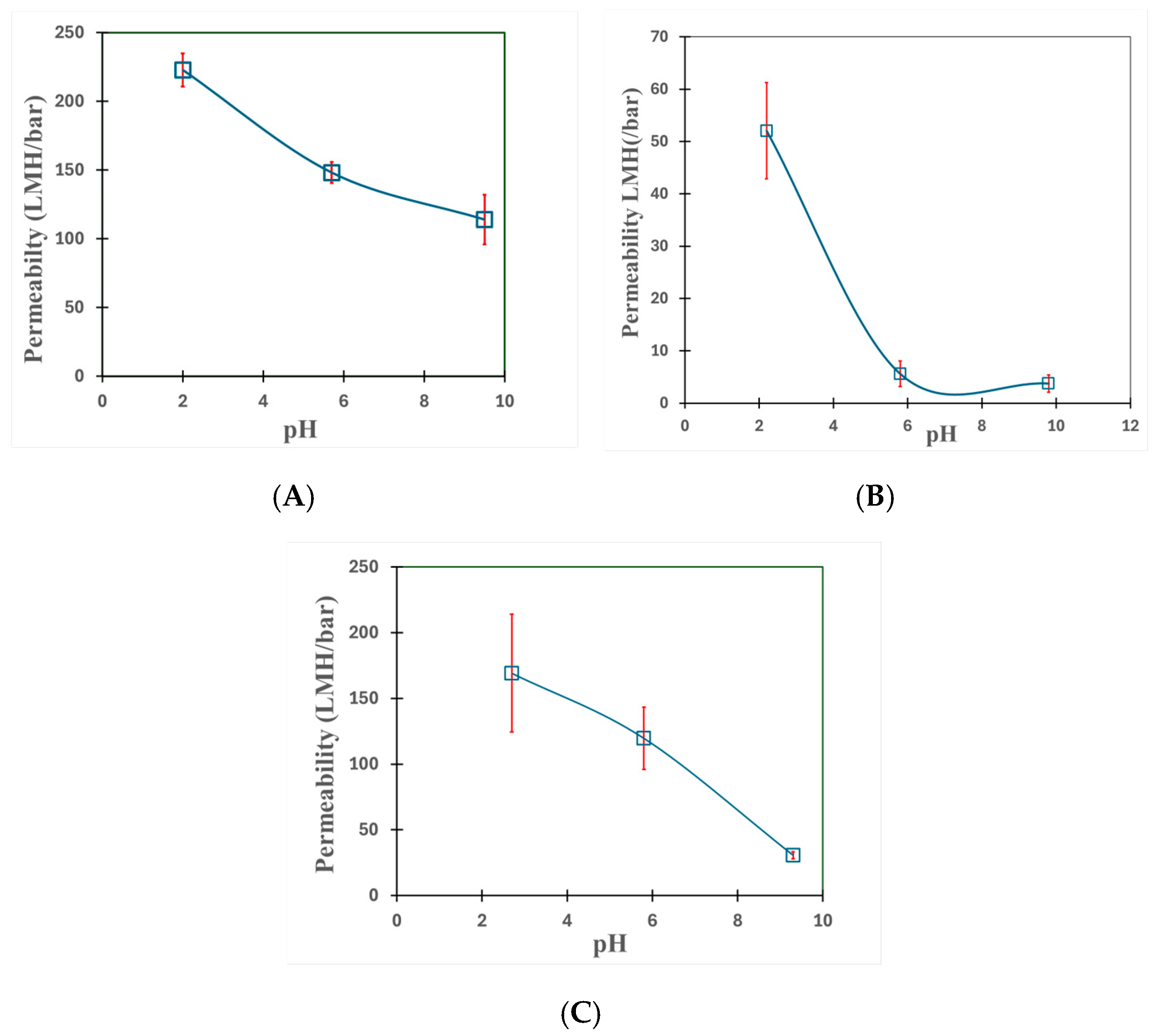

3.1. Understanding the Extent of Functionalization of Microfiltration Membrane and Fiber Media

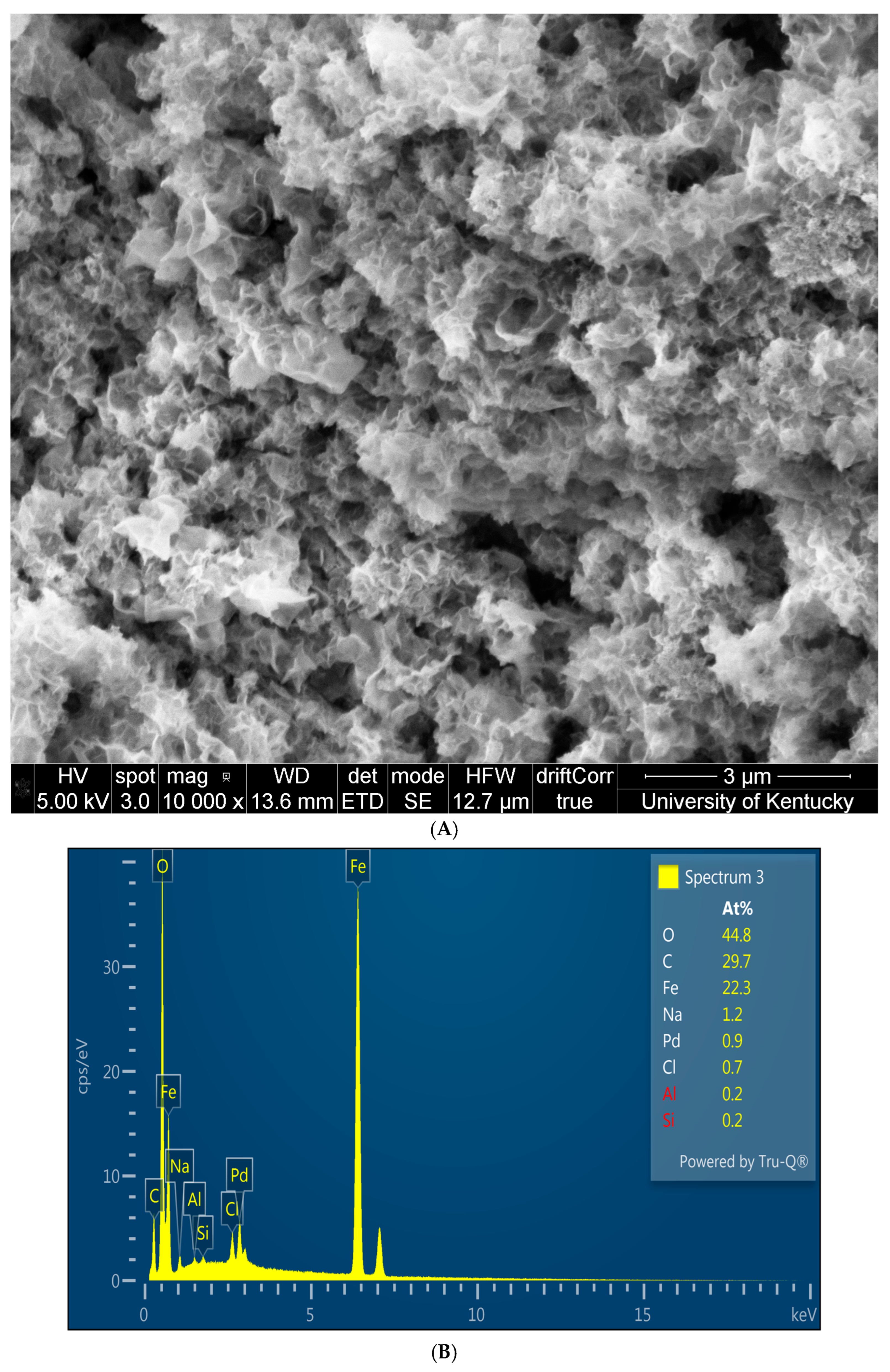

3.2. Solution Phase Nanoparticles

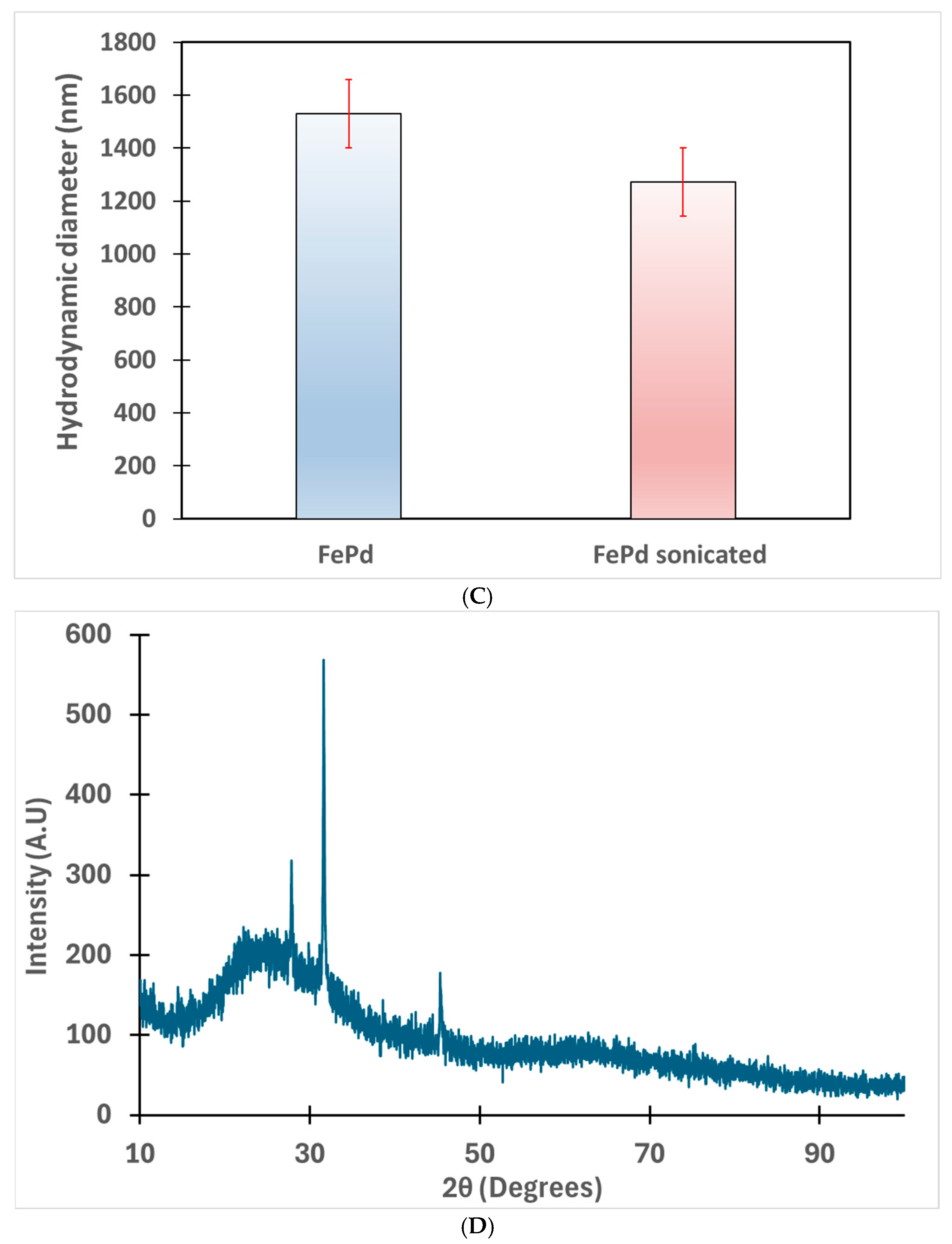

3.3. Fe/Pd In Situ Nanoparticles Within Microfiltration Membrane Domain

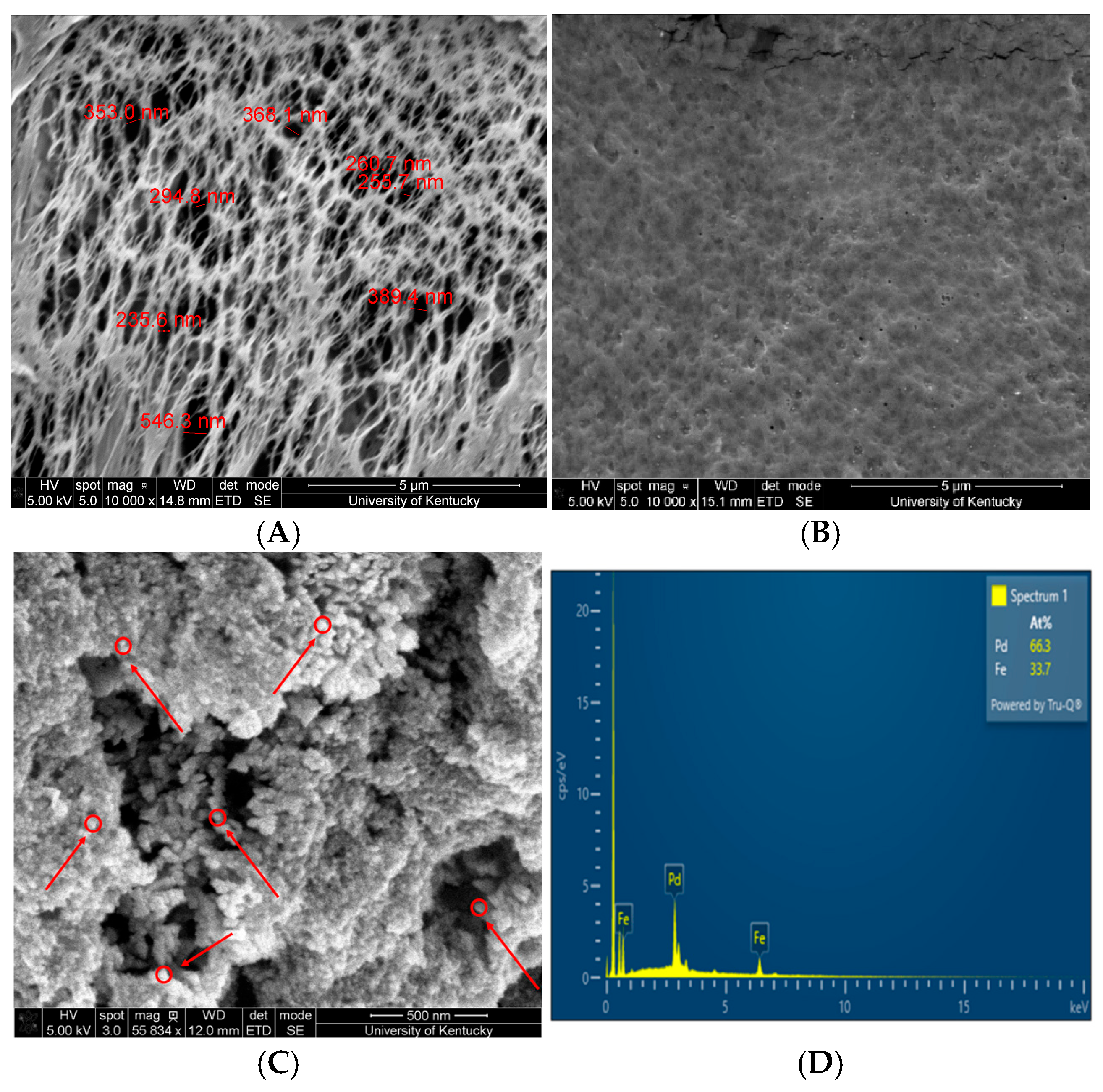

3.4. Halo-Organic Degradation Studies in Batch and Convective Flow Mode

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFAS | Per/Polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid |

| PMAA | Poly methacrylic acid |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| PE | Polyester |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDX | Energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TCE | Trichloroethylene |

| PCB | Polychlorinated biphenyl |

References

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Liu, G.; Balaram, V.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Lu, Z.; Stock, F.; Carmona, E.; Teixeira, M.R.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; et al. Worldwide cases of water pollution by emerging contaminants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2311–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; De Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; Van Leeuwen, S.P.J. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: Terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2011, 7, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, V.; Ullberg, M.; McCleaf, P.; Wålinder, M.; Köhler, S.J.; Ahrens, L. The Price of Really Clean Water: Combining Nanofiltration with Granular Activated Carbon and Anion Exchange Resins for the Removal of Per- And Polyfluoralkyl Substances (PFASs) in Drinking Water Production. ACS EST Water 2021, 1, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brase, R.A.; Mullin, E.J.; Spink, D.C. Legacy and Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Analytical Techniques, Environmental Fate, and Health Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyllenhammar, I.; Benskin, J.P.; Sandblom, O.; Berger, U.; Ahrens, L.; Lignell, S.; Wiberg, K.; Glynn, A. Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) in Children’s Serum and Contribution from PFAA-Contaminated Drinking Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11447–11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayev, M.; Capozzi, S.L.; Miller, P.; McLaughlin, K.R.; Medina, S.S.; Byrne, S.; Zheng, G.; Salamova, A. PFAS in drinking water and serum of the people of a southeast Alaska community: A pilot study. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 305, 119246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelsen, M.; Weber, R.; Panglisch, S. Minimizing the environmental impact of PFAS by using specialized coagulants for the treatment of PFAS polluted waters and for the decontamination of firefighting equipment. Emerg. Contam. 2021, 7, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsadik, A.; Akintunde, O.O.; Habibi, H.R.; Achari, G. PFAS in water environments: Recent progress and challenges in monitoring, toxicity, treatment technologies, and post-treatment toxicity. Environ. Syst. Res. 2025, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Abdelsamad, A.M.; Saeidi, N.; Mackenzie, K. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for rapid removal of PFOA: Impact of surface functional groups on adsorption efficiency and adsorbent regeneration. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 383, 126796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aedan, Y.; Altaee, A.; Shon, H.K. Performance of pressure stimuli-responsive nanofiltration and cellulose acetate forward osmosis membranes for PFOA contaminated wastewater treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yu, J.; Yuan, J.; Lu, Y.; Pang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, A.; Xiao, W.; Tang, L. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment and their removal by advanced oxidation processes. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriac, F.L.; Stoica, C.; Iftode, C.; Pirvu, F.; Petre, V.A.; Paun, I.; Pascu, L.F.; Vasile, G.G.; Nita-Lazar, M. Bacterial Biodegradation of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorosulfonic Acid (PFOS) Using Pure Pseudomonas Strains. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Ruiz, B.; Ribao, P.; Diban, N.; Rivero, M.J.; Ortiz, I.; Urtiaga, A. Photocatalytic degradation and mineralization of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) using a composite TiO2 −rGO catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junker, A.L.; Juve, J.-M.A.; Bai, L.; Christensen, C.S.Q.; Ahrens, L.; Cousins, I.T.; Ateia, M.; Wei, Z. Best Practices for Experimental Design, Testing, and Reporting of Aqueous PFAS-Degrading Technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 8939–8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanninayake, D.M. Comparison of currently available PFAS remediation technologies in water: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezugbe, E.O.; Rathilal, S. Membrane Technologies in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Membranes 2020, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mehejabin, F.; Momtahin, A.; Tasannum, N.; Faria, N.T.; Mofijur, M.; Hoang, A.T.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Mahlia, T. Strategies to improve membrane performance in wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Vogler, R.J.; Al Hasnine, S.M.A.; Hernández, S.; Malekzadeh, N.; Hoelen, T.P.; Hatakeyama, E.S.; Bhattacharyya, D. Mercury Removal from Wastewater Using Cysteamine Functionalized Membranes. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 22255–22267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman-Leach, M.; Bukowski, J.; Horn, E.; Thompson, S.; Chwatko, M.; Bhattacharyya, D. Tunable retention and recovery via pore-to-particle interactions in amine functionalized micro- and ultrafiltration Membranes: Towards scalable viral vector purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 737, 124572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Yuan, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Polymeric nanocomposite membranes for water treatment: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.; Pazirofteh, M.; Dehghani, M.; Asghari, M.; Rezakazemi, M.; Valderrama, C.; Cortina, J.-L. Application of ZnO nanostructures in ceramic and polymeric membranes for water and wastewater technologies: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 391, 123475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, M.; Phillip, W.A. The Future of Seawater Desalination: Energy, Technology, and the Environment. Science 2011, 333, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.B.; Kamcev, J.; Robeson, L.M.; Elimelech, M.; Freeman, B.D. Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 2017, 356, eaab0530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, Z.Z.; Zaidi, N.S.; Syafiuddin, A.; Yong, E.L.; Boopathy, R.; Kueh, A.B.H.; Prastyo, D.D. Shifting from Conventional to Organic Filter Media in Wastewater Biofiltration Treatment: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, M. Advanced functional polymer membranes. Polymer 2006, 47, 2217–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Urban, M.W. Recent advances and challenges in designing stimuli-responsive polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Isner, A.; Waldrop, K.; Saad, A.; Takigawa, D.; Bhattacharyya, D. Development of bench and full-scale temperature and pH responsive functionalized PVDF membranes with tunable properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 457, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Hernández, S.; Wan, H.; Ormsbee, L.; Bhattacharyya, D. Role of membrane pore polymerization conditions for pH responsive behavior, catalytic metal nanoparticle synthesis, and PCB degradation. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 555, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.; Mills, R.; Wan, H.; Ormsbee, L.; Bhattacharyya, D. Thermoresponsive PNIPAm–PMMA-Functionalized PVDF Membranes with Reactive Fe–Pd Nanoparticles for PCB Degradation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 16614–16625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, A.C.; Zhang, M.; Lin, Z. Water treatment via non-membrane inorganic nanoparticles/cellulose composites. Mater. Today 2021, 50, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, G.-X.; Chen, Q.; Shao, R.-R.; Sun, H.-H.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, D.-H. Encapsulating lipase on the surface of magnetic ZIF-8 nanosphers with mesoporous SiO2 nano-membrane for enhancing catalytic performance. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 109751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Mao, Z.; Qu, R.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Luo, X.; Shi, M.; Mao, X.; Ding, J.; Liu, B. Electrochemical hydrogenation of oxidized contaminants for water purification without supporting electrolyte. Nat. Water 2023, 1, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Tang, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Jin, Z.; Li, P.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, H.; Yu, G. Intermetallic Single-Atom Alloy In–Pd Bimetallene for Neutral Electrosynthesis of Ammonia from Nitrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 13957–13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Sun, J.-F.; Liu, J.; Liu, R.; Jiang, G. Critical Review of Pd-Catalyzed Reduction Process for Treatment of Waterborne Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3079–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Electrocatalytic hydro-dehalogenation of halogenated organic pollutants from wastewater: A critical review. Water Res. 2023, 234, 119810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, B.P.; Reinhard, M.; Schneider, W.F.; Schüth, C.; Shapley, J.R.; Strathmann, T.J.; Werth, C.J. Critical Review of Pd-Based Catalytic Treatment of Priority Contaminants in Water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3655–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, J.; Takahashi, H.; Morikawa, M. Organic syntheses by means of noble metal compounds XVII. Reaction of π-allylpalladium chloride with nucleophiles. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965, 6, 4387–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Sun, X.; Yao, Q.; Huang, M.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Z.-H. Porous carbon-confined palladium nanoclusters for selective dehydrogenation of formic acid and hexavalent chromium reduction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 104, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.M.; Rusho, M.A.; Muniyandy, E.; Diab, M.; Abilkasimov, A.; Madaminov, B.; Atamuratova, Z.; Smerat, A.; Issa, S.K.; Arabi, A.I.A.; et al. Palladium nanoparticles immobilized on magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles facilitated by Artemisia absinthium extract as an effective nanocatalyst for Heck–Mizoroki coupling reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 1039, 123765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Briot, N.J.; Saad, A.; Ormsbee, L.; Bhattacharyya, D. Pore functionalized PVDF membranes with in-situ synthesized metal nanoparticles: Material characterization, and toxic organic degradation. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 530, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, S.; Gutierrez, A.M.; Bukowski, J.; Bhattacharyya, D. Microfiltration Membrane Pore Functionalization with Primary and Quaternary Amines for PFAS Remediation: Capture, Regeneration, and Reuse. Molecules 2024, 29, 4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, M.E.; Thum, M.D.; Weise, N.K.; Daniels, G.C. PFAS removal from water using quaternary amine functionalized porous polymers. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Joseph, S.; Aluru, N.R. Effect of Cross-Linking on the Diffusion of Water, Ions, and Small Molecules in Hydrogels. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 3512–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Islam, S.; Briot, N.J.; Schnobrich, M.; Pacholik, L.; Ormsbee, L.; Bhattacharyya, D. Pd/Fe nanoparticle integrated PMAA-PVDF membranes for chloro-organic remediation from synthetic and site groundwater. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 594, 117454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koto, N.; Soegijono, B. Effect of Rice Husk Ash Filler of Resistance Against of High-Speed Projectile Impact on Polyester-Fiberglass Double Panel Composites. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1191, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, X.; Liu, B.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Liang, S.; Chu, L.-Y.; Crittenden, J. PVDF blended PVDF-g-PMAA pH-responsive membrane: Effect of additives and solvents on membrane properties and performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 541, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, R.; Chen, C.; Chen, B.; Zhu, X. High-Flux pH-Responsive Ultrafiltration Membrane for Efficient Nanoparticle Fractionation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 56575–56583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groll, J.; Ademovic, Z.; Ameringer, T.; Klee, D.; Moeller, M. Comparison of Coatings from Reactive Star Shaped PEG-stat-PPG Prepolymers and Grafted Linear PEG for Biological and Medical Applications. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalousha, M.; Manciulea, A.; Cumberland, S.; Kendall, K.; Lead, J.R. Aggregation and surface properties of iron oxide nanoparticles: Influence of ph and natural organic matter. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2008, 27, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentili, D.; Ori, G. Reversible assembly of nanoparticles: Theory, strategies and computational simulations. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 14385–14432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeks, N.D.; Smuleac, V.; Stevens, C.; Bhattacharyya, D. Iron-Based Nanoparticles for Toxic Organic Degradation: Silica Platform and Green Synthesis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 9581–9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detisch, M.J.; Balk, T.J.; Bezold, M.; Bhattacharyya, D. Nanoporous metal–polymer composite membranes for organics separations and catalysis. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 2629–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craven, J.; Sultan, M.A.; Sarma, R.; Wilson, S.; Meeks, N.; Kim, D.Y.; Hastings, J.T.; Bhattacharyya, D. Rhodopseudomonas palustris-based conversion of organic acids to hydrogen using plasmonic nanoparticles and near-infrared light. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 41218–41227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Sultan, M.A.; Kim, D.Y.; Meeks, N.; Hastings, J.T.; Bhattacharyya, D. Effect of silica-core gold-shell nanoparticles on the kinetics of biohydrogen production and pollutant hydrogenation via organic acid photofermentation over enhanced near-infrared illumination. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 7821–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Elias, W.C.; Heck, K.N.; Luo, Y.-H.; Lai, Y.S.; Jin, Y.; Gu, H.; Donoso, J.; Senftle, T.P.; Zhou, C.; et al. Hydrodefluorination of Perfluorooctanoic Acid in the H2-Based Membrane Catalyst-Film Reactor with Platinum Group Metal Nanoparticles: Pathways and Optimal Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16699–16707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microfiltration Media | Functionalization | Catalyst Incorporation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Microfiltration membrane PVDF 650 | 15 wt% PMAA and 1 mol% APS + 1 mol% MBA used for functionalization to synthesize: (a) PMAA-PVDF650 | Fe/Pd nanoparticles are incorporated only in PMAA-PVDF650 membrane to synthesize Fe/Pd PMAA-PVDF650 membrane illustrated in Figure 3. |

| 2. Polymeric non-woven fiber filters (a) Bare microglass w/o polyester backing (microglass) (b) Microglass w/polyester backing (microglass composite) | 15 wt% PMAA and 1 mol% APS + 1 mol% MBA used for functionalization to synthesize: (a) PMAA–Microglass (b) PMAA–Microglass composite | The fiber filters exhibit pH-responsive water permeability; however, no catalyst is incorporated, as all hydrogenation experiments are conducted exclusively using PVDF. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bosu, S.; Thompson, S.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Meeks, N.D.; Bhattacharyya, D. Functionalization of Microfiltration Media Towards Catalytic Hydrogenation of Selected Halo-Organics from Water. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010014

Bosu S, Thompson SS, Kim DY, Meeks ND, Bhattacharyya D. Functionalization of Microfiltration Media Towards Catalytic Hydrogenation of Selected Halo-Organics from Water. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosu, Subrajit, Samuel S. Thompson, Doo Young Kim, Noah D. Meeks, and Dibakar Bhattacharyya. 2026. "Functionalization of Microfiltration Media Towards Catalytic Hydrogenation of Selected Halo-Organics from Water" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010014

APA StyleBosu, S., Thompson, S. S., Kim, D. Y., Meeks, N. D., & Bhattacharyya, D. (2026). Functionalization of Microfiltration Media Towards Catalytic Hydrogenation of Selected Halo-Organics from Water. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010014