An Experimentally Benchmarked Optical Study on Absorption Enhancement in Nanostructured a-Si/PbS Quantum Dot Tandem Solar Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

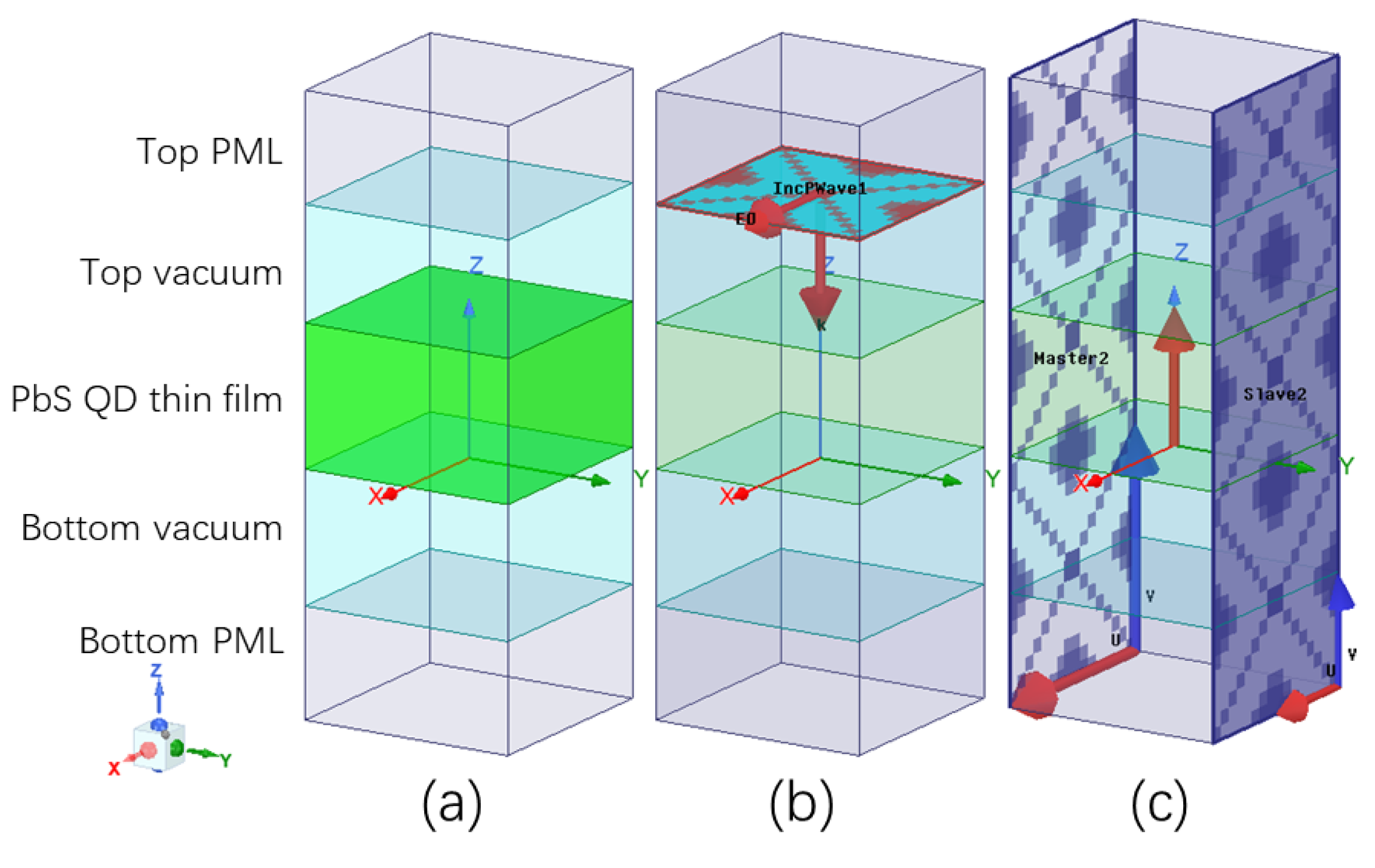

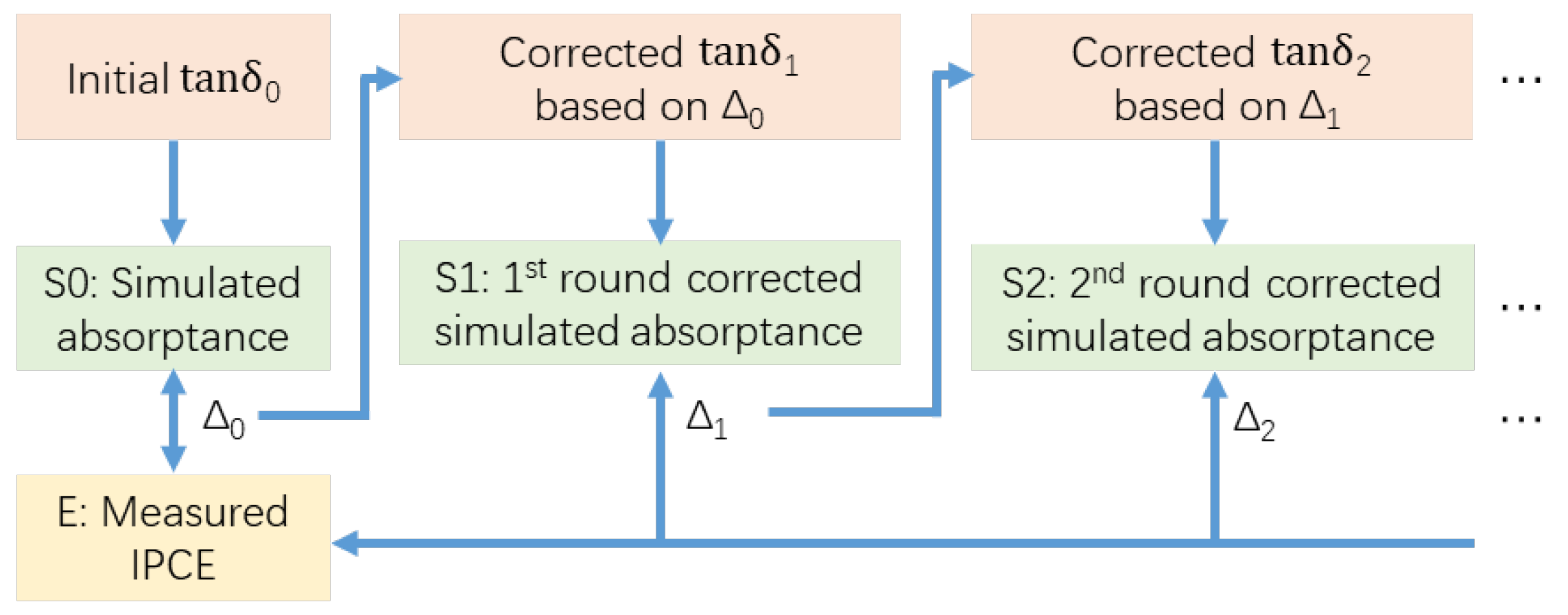

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

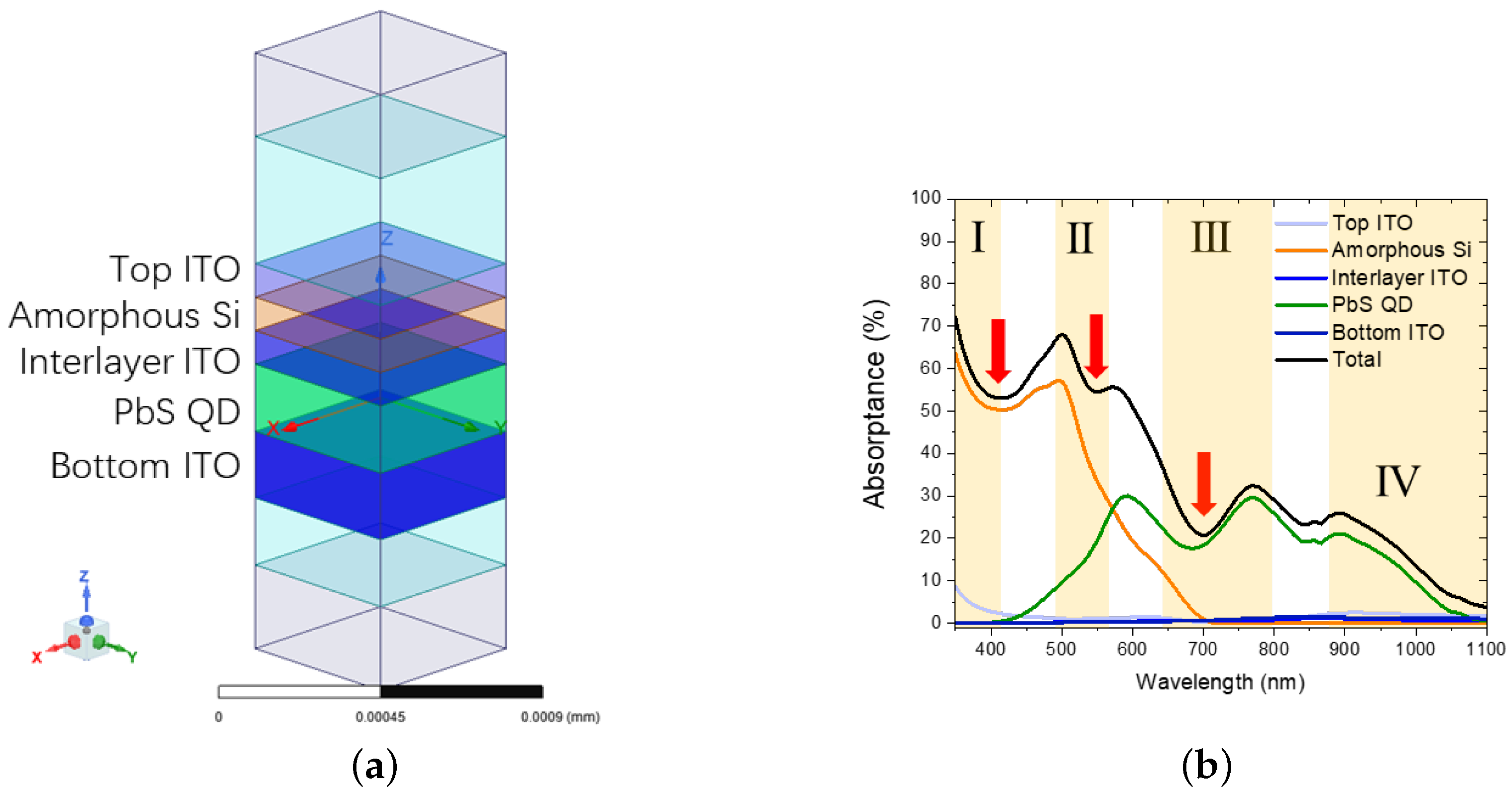

3.1. Planar Tandem Device

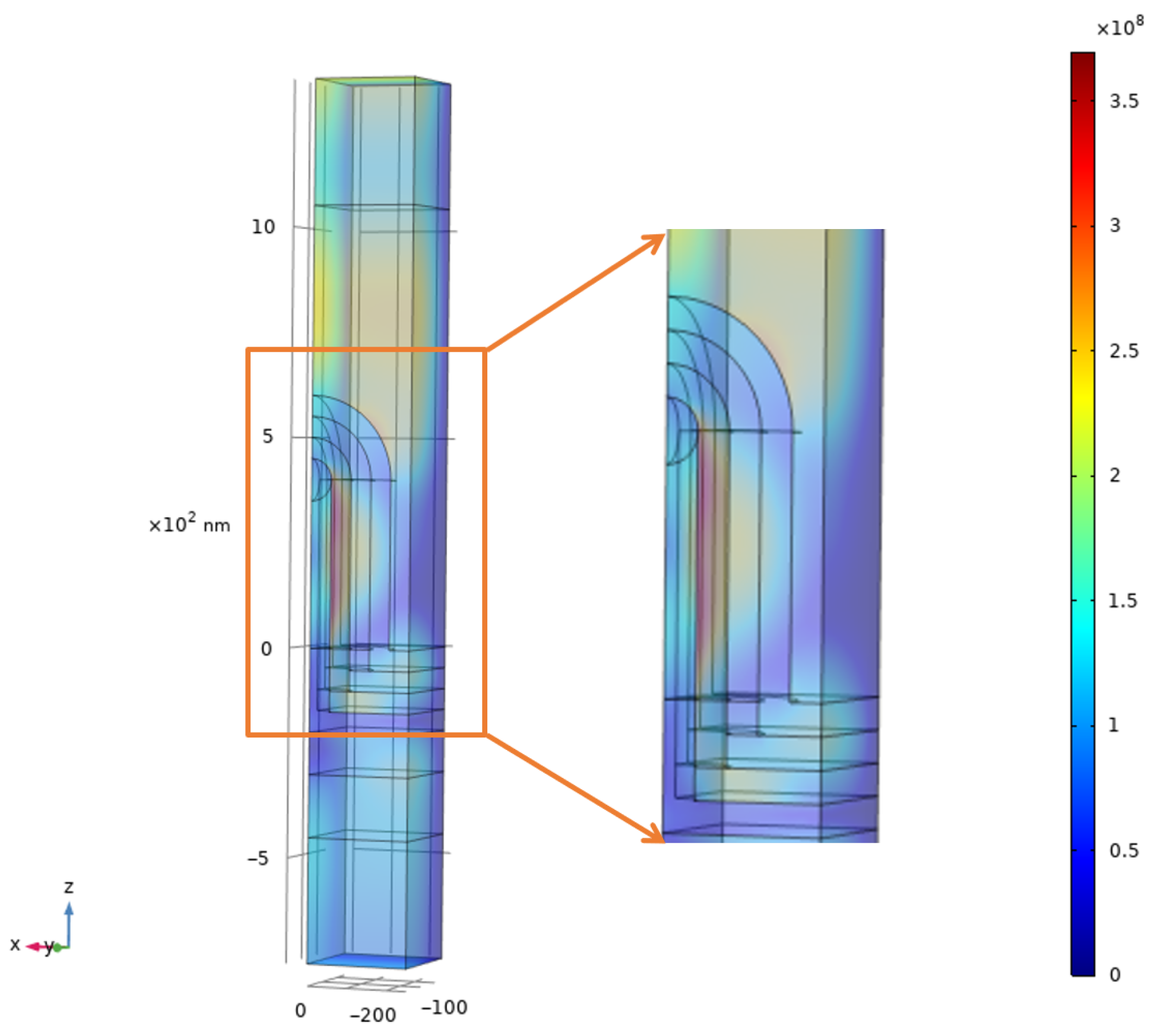

3.2. Nanostructured Tandem Device

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tress, W. Perovskite solar cells on the way to the Shockley–Queisser limit. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 17009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A.; Dunlop, E.D.; Yoshita, M.; Kopidakis, N.; Bothe, K.; Hohl-Ebinger, J.; Ho-Baillie, A.W.Y.; Lin, F.; Rohatgi, A.; Hishikawa, Y.; et al. Solar cell efficiency tables (Version 66). Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2025, 33, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, E.H. Colloidal quantum dot solar cells. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, G.H.; Abdelhady, A.L.; Ning, Z.; Thon, S.M.; Bakr, O.M.; Sargent, E.H. Colloidal quantum dot solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12732–12763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Ma, T.; Yan, J.; Khalaf, G.M.G.; Chen, C.; Hsu, H.Y.; Song, H.; Tang, J. Stable PbS colloidal quantum dot inks enable blade-coating infrared solar cells. Front. Optoelectron. 2023, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, Z.; Voznyy, O.; Pan, J.; Hoogland, S.; Adinolfi, V.; Xu, J.; Li, M.; Kirmani, A.R.; Sun, J.P.; Minor, J.; et al. Air-stable n-type colloidal quantum dot solids. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, A.H.; Thon, S.M.; Hoogland, S.; Voznyy, O.; Zhitomirsky, D.; Debnath, R.; Levina, L.; Rollny, L.R.; Carey, G.H.; Fischer, A.; et al. Hybrid passivated colloidal quantum dot solids. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.K.; Sathpathy, S.; Pandey, K.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, V.; Singh, P.K. Design and Simulation of a-Si:H/PbS Colloidal Quantum Dots Monolithic Tandem Solar Cell for 12% Efficiency. Phys. Status Solidi A 2020, 217, 2000252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; In, S.; Kim, D.w.; Lee, J.W.; Cho, N.I. Amorphous Silicon/Organic Tandem Solar Cells: A Review of Device Architectures and Light Management. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2107040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, G.; Hong, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Yuan, X.; Lin, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, T.; Song, T.; et al. Colored Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cells Exceeding 23.5% Efficiency Enabled by Luminescent Down-Shift Quantum Dots. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, W.; De Bastiani, M.; Allen, T.G.; Aydin, E.; Razzaq, A.; Rehman, A.U.; Ugur, E.; Babayigit, A.; Subbiah, A.S.; Isikgor, F.H.; et al. Photon recycling in perovskite solar cells and its impact on device design. Nanophotonics 2021, 10, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Gao, P.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, G.; Di, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Shen, W. Surface plasmon enhanced absorption in amorphous silicon solar cells by incorporating silver nanoparticles in the transparent conductive oxide layer. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 143105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, S.H.; Franzen, S. Indium Tin Oxide Plasma Frequency Dependence on Sheet Resistance and Surface Adlayers Determined by Reflectance FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 12986–12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Gilmore, C.M.; Piqué, A.; Horwitz, J.S.; Mattoussi, H.; Murata, H.; Kafafi, Z.H.; Chrisey, D.B. Electrical, optical, and structural properties of indium–tin–oxide thin films for organic light-emitting devices. J. Appl. Phys. 1999, 86, 6451–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, A.; Knight, M.; Garnett, E.C.; Ehrler, B.; Sinke, W.C. Photovoltaic materials: Present efficiencies and future challenges. Science 2016, 352, aad4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Antably, A.; Al-Ali, M.; Younes, M.; Turaev, S.; Park, J. Role of Nanostructure Technology in the Light Trapping of Solar Cells: A Review. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, S.; Kim, H.; Kwak, H.; Kang, C.; Jung, I.; Oh, S.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, J.; Park, H.J.; Lee, K.T. Dielectric light-trapping nanostructure for enhanced light absorption in organic solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 20649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Sun, X.W. Nanophotonic and Microphotonic Structures for Light Management in Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2208820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, B.; Wan, Y.; Ruan, S.; Wan, J. Recent Progress of Nanopillar Array Architectures for Photovoltaic Applications. Solar RRL 2018, 2, 1700186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Roca i Cabarrocas, P. Rational design of nanowire solar cells: From single nanowire to nanowire arrays. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, V.; Cui, Y.; Fan, S. Nearly Total Solar Absorption in Ultrathin Nanostructured Iron Oxide for Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. ACS Photonics 2014, 1, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, E.; Yang, P. Light Trapping in Silicon Nanowire Solar Cells. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, P.; Verschuuren, M.A.; Polman, A. Broadband omnidirectional antireflection coating based on subwavelength surface Mie resonators. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, H.A.; Polman, A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkapati, S.; Catchpole, K.R. Nanophotonic light trapping in solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 112, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brongersma, M.L.; Cui, Y.; Fan, S. Light management for photovoltaics using high-index nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Razavi, H.; Do, R.; Zhang, A.; Yerushalmi, T.; Chueh, Y.L.; Ford, A.C.; Ho, J.C.; Takahashi, T.; Berman, G.P.; et al. Three-dimensional nanopillar-array photovoltaics on low-cost and flexible substrates. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, H.; Li, X. Bundling of silicon nanowire arrays and its effect on their optical absorption. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 124316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Ouyang, M.; Chen, B.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, J.; Lou, N.; Dong, L.; Wang, Z.; Fu, Y. Design and Fabrication of Moth-Eye Subwavelength Structure with a Waist on Silicon for Broadband and Wide-Angle Anti-Reflection Property. Coatings 2018, 8, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hägglund, C.; Johansson, E.M.J. Electro-Optics of Colloidal Quantum Dot Solids for Thin-Film Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, C.; Cuevas, A.; De Wolf, S. Light Trapping in Solar Cells: Can Nanostructures Help? ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2790–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Li, Z.; Rusli, E.; Xu, X.; Tao, Z.; Pan, J.; Yu, X.; Yu, L.; Mokkapati, S. An optical study on the enhanced light trapping performance of the perovskite solar cell using nanocone structure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molesky, S.; Lin, Z.; Piggott, A.Y.; Jin, W.; Vuckovic, J.; Rodriguez, A.W. An introduction to inverse design for nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 2018, 12, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, J.; Rolland, T.; Drouard, E.; Chen, X.; Seassal, C. Nanophotonic Solar Cell Architectures with Light Trapping beyond the Ergodic Limit. ACS Photonics 2023, 10, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiyev, Z.; Balayeva, N.O. PbS nanostructures: A Review of recent advances. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 21, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, M.; Li, N.; Xu, Y.; Ling, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, F.; Yang, F.; Ji, K.; et al. Realizing solution-processed monolithic PbS QDs/perovskite tandem solar cells with high UV stability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 24693–24701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.R.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Chaudhuri, S. Optical properties of PbS quantum dots synthesized by a greener method. Opt. Mater. 2015, 46, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.M.; Brown, P.R.; Bulović, V.; Bawendi, M.G. High-efficiency colloidal quantum dot solar cells via robust self-assembled monolayers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3054–3059. [Google Scholar]

- Schuller, J.A.; Barnard, E.S.; Cai, W.; Jun, Y.C.; White, J.S.; Brongersma, M.L. Plasmonics for extreme light concentration and manipulation. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.T.; Lu, C.H.; Rong, C.C.; Wang, S.M.; Liu, M.H. Wide Angle of Incidence-Insensitive Polarization-Independent THz Metamaterial Absorber for Both TE and TM Mode Based on Plasmon Hybridizations. Materials 2018, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; He, W.; Yang, F.; Ran, J.; Gao, B.; Zhang, W.L. Polarization-independent and angle-insensitive broadband absorber with a target-patterned graphene layer in the terahertz regime. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 25558–25566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachowicz, T.; Ehrmann, A. Recent Developments of Solar Cells from PbS Colloidal Quantum Dots. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, A.; Yang, L.; Bai, S.; Fropf, J.S.; Lohmann, M.S.; Cao, J.; Smeets, W.C.; Friend, R.H. Perovskite/Colloidal Quantum Dot Tandem Solar Cells: Theoretical Modeling and Monolithic Structure. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palik, E.D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jellison, G.E., Jr.; Modine, F.A. Parameterization of the optical functions of amorphous materials in the interband region. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 69, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, K.; Wang, W.; Wang, X. Ultrabroadband and omnidirectional silicon nitride-based antireflection coating for silicon solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, J.M.; Law, M.; Song, Q.; Perkins, C.L.; Beard, M.C.; Nozik, A.J. Structural, Optical, and Electrical Properties of Self-Assembled Films of PbSe Nanocrystals Treated with 1,2-Ethanedithiol. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, T.A.F.; Ledin, P.A.; Russell, J.; Geldhauser, J.A.; Mahmoud, M.A.; El-Sayed, M.A.; Tsukruk, V.V. Electrically tunable plasmonic behavior of nanocrystal-polymer composites. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6182–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, F.; Werner, J.; Kamino, B.A.; Bräuninger, M.; Monnard, R.; Paviet-Salomon, B.; Barraud, L.; Ding, L.; Diaz, J.L.; Wyser, A.; et al. Fully textured monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells with 25.2% efficiency. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukharevska, N.; Bederak, D.; Goossens, V.M.; Momand, J.; Duim, H.; Dirin, D.N.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Kooi, B.J.; Loi, M.A. Scalable PbS Quantum Dot Solar Cell Production by Blade Coating from Stable Inks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 5195–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Misra, S.; Wang, J.; Qian, S.; Foldyna, M.; Xu, J.; Shi, Y.; Johnson, E.; Roca i Cabarrocas, P. Understanding Light Harvesting in Radial Junction Amorphous Silicon Thin Film Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Gao, P.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, G.; Di, Z.; Wang, W.; Shen, W. Plasmonic-enhanced solar energy harvesting in amorphous silicon thin film solar cells. Nano Energy 2015, 12, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashouri, A.; Köhnen, E.; Bor, L.; Magomedov, A.; Hempel, H.; Caprioglio, P.; Márquez, J.A.; Morales-Vilches, A.B.; Kasparavicius, E.; Smith, J.A.; et al. Monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell with >29% efficiency by enhanced hole extraction. Science 2020, 370, 1300–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, I.J.; Zhitomirsky, D.; Bass, J.D.; Rice, P.M.; Topuria, T.; Krupp, L.; Thon, S.M.; Ip, A.H.; Debnath, R.; Kim, H.-C.; et al. Ordered nanopillar structured electrodes for depleted bulk heterojunction colloidal quantum dot solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2315–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Fu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; He, R.; et al. All-perovskite tandem solar cells with 24.2% efficiency and improved stability. Nature 2022, 603, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, Q.; Li, Z. An Experimentally Benchmarked Optical Study on Absorption Enhancement in Nanostructured a-Si/PbS Quantum Dot Tandem Solar Cells. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010012

Jiang Q, Li Z. An Experimentally Benchmarked Optical Study on Absorption Enhancement in Nanostructured a-Si/PbS Quantum Dot Tandem Solar Cells. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Qinqian, and Zeyu Li. 2026. "An Experimentally Benchmarked Optical Study on Absorption Enhancement in Nanostructured a-Si/PbS Quantum Dot Tandem Solar Cells" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010012

APA StyleJiang, Q., & Li, Z. (2026). An Experimentally Benchmarked Optical Study on Absorption Enhancement in Nanostructured a-Si/PbS Quantum Dot Tandem Solar Cells. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010012