Nanoscale Characterization of Nanomaterial-Based Systems: Mechanisms, Experimental Methods, and Challenges in Probing Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Nanomaterial-Based Systems

1.2. Significance of Studying Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties of Nanomaterial-Based Systems at Nanoscale

2. Nanoscale Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Mechanisms of Nanomaterial-Based Systems

2.1. Corrosion Mechanism of Nanomaterial-Based Systems

2.2. Corrosion Resistance Mechanism Influenced by Nanomaterial-Based Systems

2.3. Mechanical Strengthening Mechanism of Nanomaterial-Based Systems

2.4. Tribological Wear Mechanism of Nanomaterial-Based Systems

3. Experimental and Computational Methods for Probing Nanoscale Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Mechanisms

3.1. Corrosion Measurement Techniques

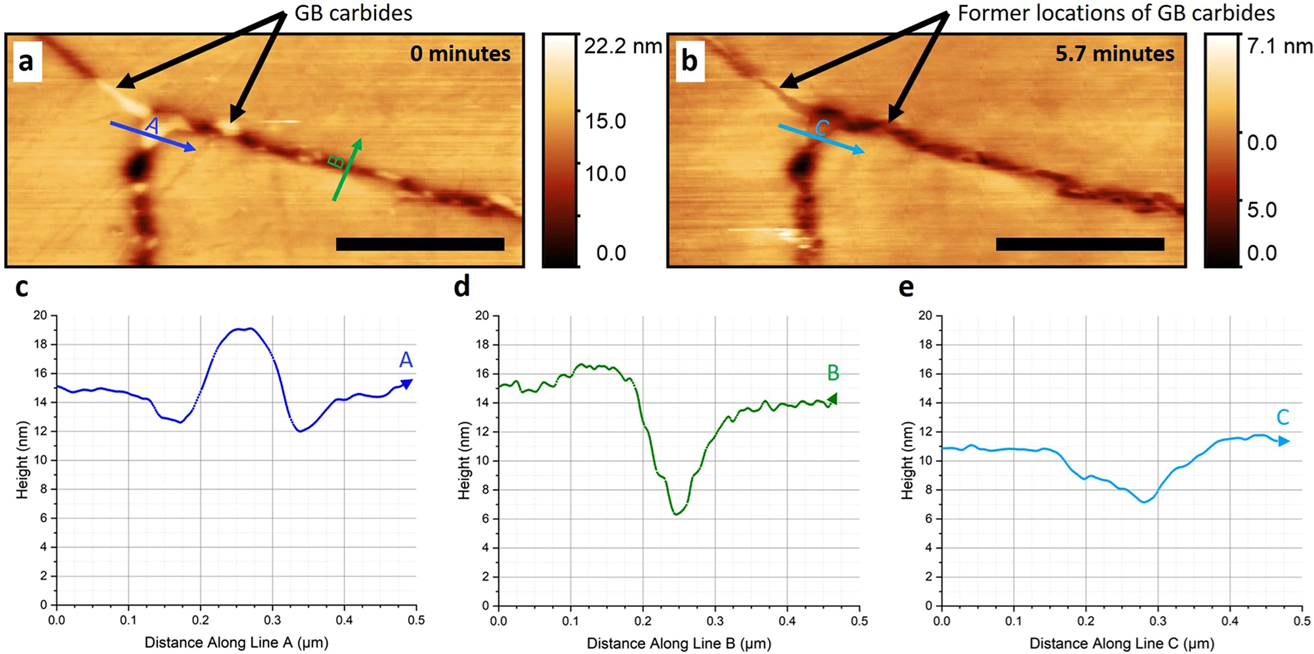

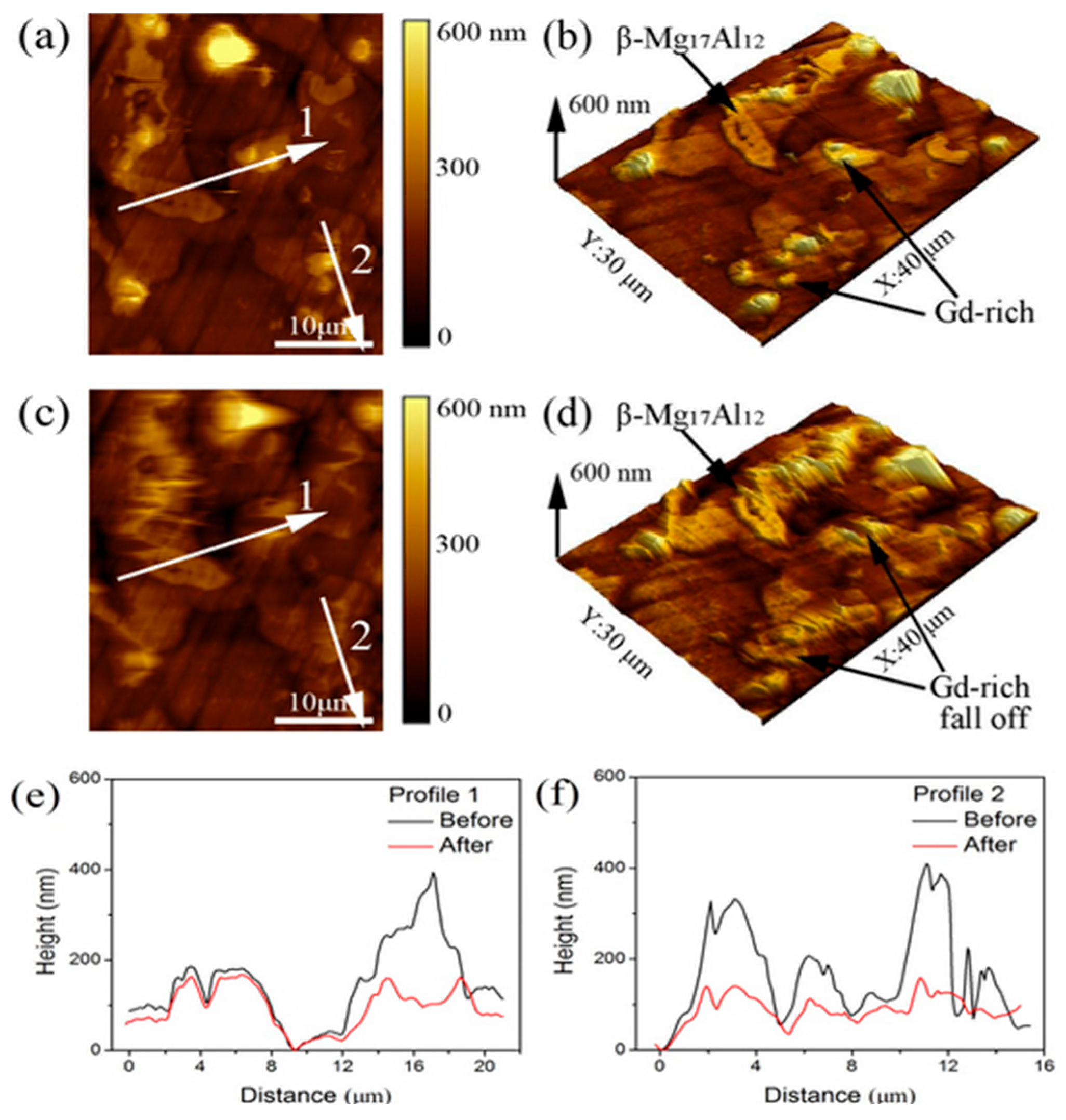

3.1.1. Advanced Force/Electron Microscopy Techniques

3.1.2. Conventional Electrochemical Techniques

3.2. Mechanical and Tribological Properties Measurement Techniques

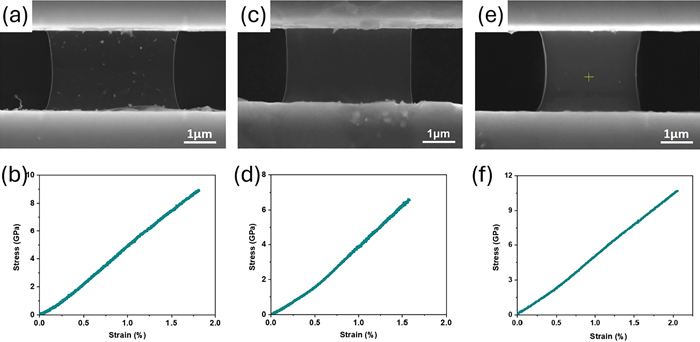

3.2.1. In Situ SEM/TEM Tensile Testing

3.2.2. Hardness and Modulus Properties Measurements

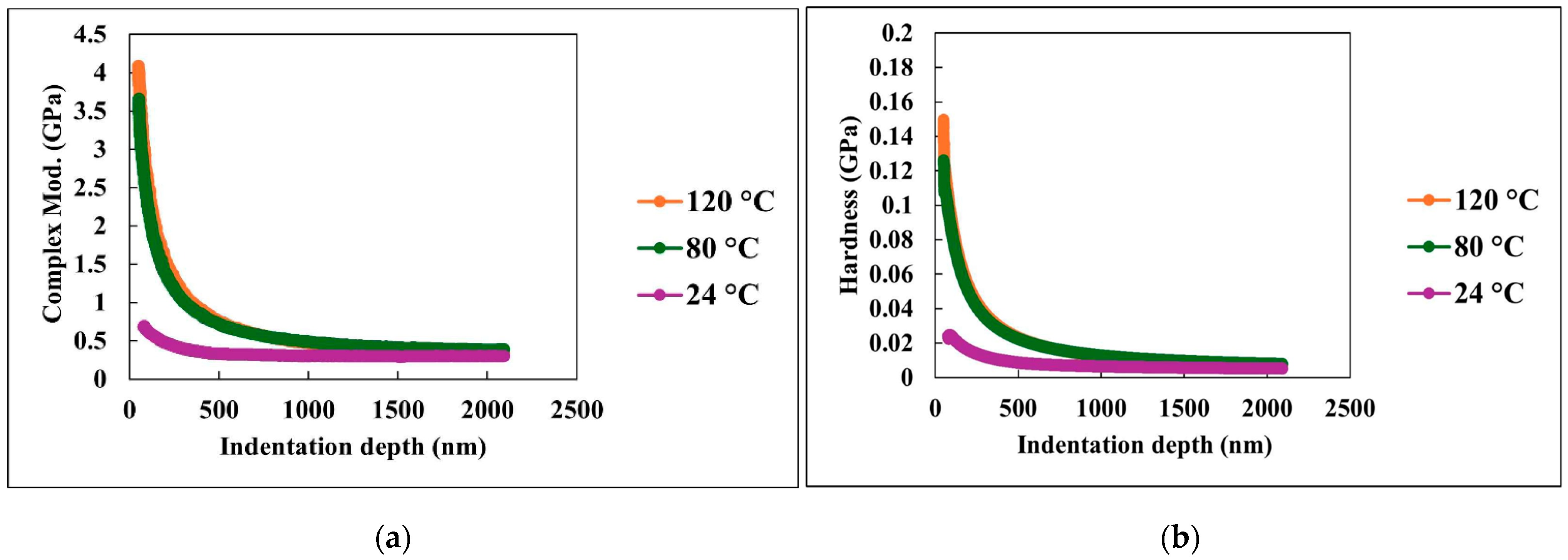

3.2.3. Viscoelastic Properties Measurements

3.2.4. Time-Dependent Nanomechanical Properties Measurements

3.2.5. Fatigue and Fracture Toughness Measurements

3.2.6. Nanoscale Tribological Test

3.2.7. Role of Computational Materials Science in Studying Nanomaterial-Based Systems at Nanoscale

4. Challenges in Characterization of Nanomaterial-Based System Properties

4.1. Challenges in Nanoscale Corrosion Measurements

4.2. Challenges in the Characterization of Nanoscale Mechanical and Tribological Properties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bromma, K.; Alhussan, A.; Perez, M.M.; Howard, P.; Beckham, W.; Chithrani, D.B. Three-Dimensional Tumor Spheroids as a Tool for Reliable Investigation of Combined Gold Nanoparticle and Docetaxel Treatment. Cancers 2021, 13, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromma, K.; Dos Santos, N.; Barta, I.; Alexander, A.; Beckham, W.; Krishnan, S.; Chithrani, D.B. Enhancing Nanoparticle Accumulation in Two Dimensional, Three Dimensional, and Xenograft Mouse Cancer Cell Models in the Presence of Docetaxel. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, V.; Ansari, M.M.; Tewari, D.; Gaur, M.; Yadav, A.B.; García-Betancourt, M.-L.; Abdel-Haleem, F.M.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Nanoparticle and Nanostructure Synthesis and Controlled Growth Methods. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yang, X.; Hu, Q.; Cai, Z.; Liu, L.-M.; Guo, L. Recent Progress of Amorphous Nanomaterials. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 8859–8941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Hou, X.; Wu, B.; Dong, J.; Yao, M. Heterogeneous Structured Nanomaterials from Carbon and Related Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2411472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuye, B.; Abera, B. Nanomaterials: An Overview of Synthesis, Classification, Characterization, and Applications. Nano Sel. 2023, 4, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harbi, N.; Abd-Elrahman, N.K. Physical Methods for Preparation of Nanomaterials, Their Characterization and Applications: A Review. J. Umm Al Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 2024, 11, 356–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paras; Yadav, K.; Kumar, P.; Teja, D.R.; Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Mohapatra, S.S.; Sahoo, A.; Chou, M.M.C.; Liang, C.-T.; et al. A Review on Low-Dimensional Nanomaterials: Nanofabrication, Characterization and Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 13, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Kang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Jiang, Z. Carbon-Based Stimuli-Responsive Nanomaterials: Classification and Application. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2023, 4, 0022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozhdestvenskiy, O.I.; Lalitha, Y.S.; Ikram, M.; Gupta, M.; Jain, A.; Verma, R.; Sood, S. Advances in Nanomaterials: Types, Synthesis, and Manufacturing Methods. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 588, 02005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Shoukat, A.; Ayub, A.; Razzaq, B.; Tahir, M.B. Types and Classification of Nanomaterials. In Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Characterization, Hazards and Safety; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 31–54. ISBN 978-0-12-823823-3. [Google Scholar]

- Harish, V.; Tewari, D.; Gaur, M.; Yadav, A.B.; Swaroop, S.; Bechelany, M.; Barhoum, A. Review on Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Materials: Bioimaging, Biosensing, Drug Delivery, Tissue Engineering, Antimicrobial, and Agro-Food Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Hassan, A.I. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanomaterials for Application in Cost-Effective Electrochemical Devices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.; Mia, M.F.; Wiggins, J.; Desai, S. Nanomaterials for Energy Storage Systems—A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Farghali, M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Badr, M.M.; Ihara, I.; Rooney, D.W.; et al. Synthesis of Green Nanoparticles for Energy, Biomedical, Environmental, Agricultural, and Food Applications: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.A.; Abd-Elaziem, W.; Elsheikh, A.; Zayed, A.A. Advancements in Nanomaterials for Nanosensors: A Comprehensive Review. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 4015–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, S.M.; Walczak, M.; Stefano, M.D.; Ruggiero, A.; Rosenkranz, A.; Marian, M. 2D Materials for Tribo-Corrosion and -Oxidation Protection: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 331, 103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AhadiParsa, M.; Dehghani, A.; Ramezanzadeh, M.; Ramezanzadeh, B. Rising of MXenes: Novel 2D-Functionalized Nanomaterials as a New Milestone in Corrosion Science—A Critical Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 307, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari, M.H.; Zhang, Y.; Mahmoodi, A.; Xu, G.; Yu, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, X. Nanocomposite Organic Coatings for Corrosion Protection of Metals: A Review of Recent Advances. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 162, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabhan, F.; Fayyad, E.M.; Sliem, M.H.; Shurrab, F.M.; Eid, K.; Nasrallah, G.; Abdullah, A.M. ZnO-Doped gC3N4 Nanocapsules for Enhancing the Performance of Electroless NiP Coating—Mechanical, Corrosion Protection, and Antibacterial Properties. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 22361–22381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, C.; Berdimurodov, E.; Verma, D.K.; Berdimuradov, K.; Alfantazi, A.; Hussain, C.M. 3D Nanomaterials: The Future of Industrial, Biological, and Environmental Applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 156, 111163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Raman, A.P.S.; Singh, M.B.; Massey, I.; Singh, P.; Verma, C.; AlFantazi, A. Green Nanoparticles for Advanced Corrosion Protection: Current Perspectives and Future Prospects. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2024, 21, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, T.Y.; Hegde, A.C. Electrochemical Development and Characterisation of Nanostructured Ni–Fe Alloy Coatings for Corrosion Protection. Can. Metall. Q. 2025, 64, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, F.; Volpe, A. Superhydrophobic Coatings for Corrosion Protection of Stainless Steel. Aerospace 2024, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.-W.; Lian, I.; Zhou, J.; Bernazzani, P.; Jao, M.; Hoque, M.A. Corrosion Resistance and Nano-Mechanical Properties of a Superhydrophobic Surface. Lubricants 2025, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, L.M. Nanocomposite Coatings for Anti-Corrosion Properties of Metallic Substrates. Materials 2023, 16, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.A.; Raina, A.; Mohan, S.; Singh, R.A.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Haq, M.I.U. Nanostructured Coatings: Review on Processing Techniques, Corrosion Behaviour and Tribological Performance. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deyab, M.A.; Alghamdi, M.M.; El-Zahhar, A.A.; El-Shamy, O.A.A. Advantages of CoS2 Nano-Particles on the Corrosion Resistance and Adhesiveness of Epoxy Coatings. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoque, M.A.; Yao, C.-W.; Khanal, M.; Lian, I. Tribocorrosion Behavior of Micro/Nanoscale Surface Coatings. Sensors 2022, 22, 9974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cao, L.; Wang, W.; Mao, Z.; Han, D.; Pei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, W.; Li, W.; Chen, S. Construction of Smart Coatings Containing Core-Shell Nanofibers with Self-Healing and Active Corrosion Protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 42748–42761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, B.; Cavaliere, P.; Shabani, A.; Pruncu, C.I.; Lamberti, L. Nano-Scale Wear: A Critical Review on Its Measuring Methods and Parameters Affecting Nano-Tribology. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2024, 238, 125–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xing, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, B.; Huang, P.; Liu, L. Controllable Interface-Tailored Strategy to Reduce the Nanotribological Properties of Ti3C2Tx by Depositing MoS2 Using Atomic Layer Deposition. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 075706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, C.; Kooi, S.E.; Veysset, D.; Guo, C.; Gan, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Chen, G.; Naraghi, M.; Nelson, K.A.; et al. Tough Monolayer Silver Nanowire-Reinforced Double-Layer Graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 55899–55912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Katiyar, L.K.; Sasikumar, C. Influence of Radial Distance from Plasma Stealth Center on Nano-Mechanical and Hydrophobic Characteristics of Diamond-like Carbon/Cu Composite Films Synthesized via PECVD. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 152, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, T.; Saleem, S.S. Comparative Investigation and Characterization of the Nano-Mechanical and Tribological Behavior of RF Magnetron Sputtered TiN, CrN, and TiB2 Coating on Ti6Al4V Alloy. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, C.-L.; You, J.-D.; Chen, J.-J.; Liang, S.-C.; Chung, T.-F.; Yang, Y.-L.; Ii, S.; Ohmura, T.; Zheng, X.; Chen, C.-Y.; et al. In-Situ Transmission Electron Microscopy Investigation of the Deformation Mechanism in CoCrNi and CoCrNiSi0.3 Nanopillars. Scr. Mater. 2025, 255, 116405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, M.Y.; Norkus, T. Introducing a Nano-Scale Surface Morphology Parameter Affecting Fracture Properties of CNT Nanocomposites. Compos. Commun. 2024, 48, 101931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasiewicz, K. Studies of Nanoscratching in the Aspect of Homogeneity of Adhesive Joints. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 24, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Shangguan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hauwiller, M.; Yu, H.; Nie, Y.; Bustillo, K.C.; Alivisatos, A.P.; Asta, M.; Zheng, H. Unveiling Corrosion Pathways of Sn Nanocrystals through High-Resolution Liquid Cell Electron Microscopy. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 1168–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanijo, E.O.; Thomas, J.G.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, W.; Brand, A.S. Surface Characterization Techniques: A Systematic Review of Their Principles, Applications, and Perspectives in Corrosion Studies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 111502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, J.R.; Vinodhini, S.P.; Shanmuga Sundari, C.; Dhanalakshmi, C.; Raja Beryl, J. Electrochemical Characterizations of the Anticorrosive Nanoscale Polymer-Based Coatings. In Polymer-Based Nanoscale Materials for Surface Coatings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 383–408. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, K.-X.; Lai, T.; Chen, Y.; Yin, Z.; Wu, Z.-Q.; Yan, H.; Song, H.-G.; Luo, C.; Hu, Z. Micro-Galvanic Corrosion Behaviour of Mg−(7,9)Al−1Fe−xNd Alloys. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2024, 34, 2828–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarri, S.; Lloyd, M.; Darnbrough, E.; Armstrong, D. Quantifying Delamination Energy in Tungsten on Silicon Thin Films through Nanoindentation and Nanoscratch. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, J. Control of Fracture Toughness of Kerogen on Artificially-Matured Shale Samples: An Energy-Based Nanoindentation Analysis. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 124, 205266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavdekar, S.; Rudawski, N.G.; Basu, S.; Subhash, G. Microstructural Characterization and Nanomechanical Properties of Multilayer Graphene on Metal Substrates. JOM 2024, 76, 1618–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizuela-Colmenares, N.; Pérez-Andrade, L.I.; Perez, S.; Brewer, L.N.; Muñoz-Saldaña, J. Mechanical and Microstructural Behavior of Inconel 625 Deposits by High-Pressure Cold Spray and Laser Assisted Cold Spray. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 485, 130917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y. Using Nanoindentation to Characterize the Mechanical and Creep Properties of Shale: Load and Loading Strain Rate Effects. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 14317–14331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.M.Y.; Fan, Z.; Wang, K.; Yan, Y.; Badhan, N.A.; Fan, X. Effects of Al Addition on the Mechanical and Corrosion Properties of NbTaTiV High-Entropy Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1039, 183156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, D.; Zhang, M.; Meng, S.; Wang, S.; Su, Y.; Long, X. Application of Nano-Scratch Technology to Identify Continental Shale Mineral Composition and Distribution Length of Bedding Interfacial Transition Zone—A Case Study of Cretaceous Qingshankou Formation in Gulong Depression, Songliao Basin, NE China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 234, 212674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, P.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H. Atomic-Scale Understanding of Oxidation Mechanisms of Materials by Computational Approaches: A Review. Mater. Des. 2022, 217, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Ji, Y.; Wei, X.; Xu, A.; Chen, D.; Li, N.; Kong, D.; Luo, X.; Xiao, K.; Li, X. Integrated Computation of Corrosion: Modelling, Simulation and Applications. Corros. Commun. 2021, 2, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Rong, J.; Bu, J.; Sui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y. Electrochemical Model of Anodic Dissolution for Magnesium Nanoparticles. Ionics 2024, 30, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, W.; Hao, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D. Self-healing Anti-corrosion Coatings: A Mechanism Study Using Computational Materials Science. Electr. Mater. Appl. 2024, 1, e12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, J.; Ding, D.; Hou, D. Nanoscale Insights on the Stress Corrosion Mechanism of Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Yu, S.; Yao, L.; Xu, Y. Atomic-Scale Investigation of the Tribological Behaviors of Titanium Alloy Interfaces with 2D Nanomaterials. Langmuir 2025, 41, 16938–16951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deka, S.; Mozafari, F.; Mallick, A. Microstructural, Mechanical, Tribological, and Corrosion Behavior of Ultrafine Bio-Degradable Mg/CeO2 Nanocomposites: Machine Learning-Based Modeling and Experiment. Tribol. Int. 2023, 190, 109063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofokeng, T.G.; Motloung, M.P.; Ama, O.M.; Ray, S.S. Electrochemical Characterization of Nanomaterials. In Characterization of Nanomaterials; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Han, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Ding, H.; Zheng, K.; Pan, F. Investigation on the Interface Bonding and Reinforcement Mechanism of Nano Ti/AZ31 Magnesium Matrix Composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 4908–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Taniguchi, D.; Okamoto, T.; Hirata, K.; Ozawa, T.; Fukuma, T. Nanoscale Corrosion Mechanism at Grain Boundaries of the Al–Zn–Mg Alloy Investigated by Open-Loop Electric Potential Microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 5281–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Dong, S.; Xu, M. Electrochemical Origin for Mitigated Pitting Initiation in AA7075 Alloy with TiB2 Nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 601, 154275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Song, G.; Yun, B.; Kim, T.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, H.; Doo, S.W.; Lee, K.T. Revealing the Nanoscopic Corrosive Degradation Mechanism of Nickel-Rich Layered Oxide Cathodes at Low State-of-Charge Levels: Corrosion Cracking and Pitting. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 10566–10581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Collins, L.; Balke, N.; Liaw, P.K.; Yang, B. In-Situ Electrochemical-AFM Study of Localized Corrosion of Al CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloys in Chloride Solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, R.; Zou, L.; Chi, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Chen, J. Influence of Grain Boundary Precipitates on Intergranular Corrosion Behavior of 7050 Al Alloys. Coatings 2022, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Z.; Yin, X.; Tang, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y. Phase-Field Investigation of Intergranular Corrosion Mechanism and Kinetics in Aluminum Alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 8841–8853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Deng, R.; Kong, X.; Parande, G.; Hu, J.; Peng, P.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, B.; Wang, G.; Gupta, M.; et al. Interfacial Characterization and Its Influence on the Corrosion Behavior of Mg-SiO2 Nanocomposites. Acta Mater. 2022, 230, 117840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Nishimoto, M.; Takaya, M.; Muto, I. In Situ Microscopy and Electrochemical Characteristics of Initiation of Intergranular Corrosion of Aging-Treated Al–1Mg–0.65Si–0.8Cu Alloy in 0.1 M NaCl. Corros. Sci. 2025, 252, 112985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Cao, L. Microstructure and Its Effect on the Intergranular Corrosion Properties of 2024-T3 Aluminum Alloy. Crystals 2022, 12, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettayeb, M.; Maurice, V.; Klein, L.H.; Lapeire, L.; Verbeken, K.; Marcus, P. Nanoscale Intergranular Corrosion and Relation with Grain Boundary Character as Studied In Situ on Copper. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, C835–C841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, B.O.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; You, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Han, E.-H. Multifaceted Study of the Galvanic Corrosion Behaviour of Titanium-TC4 and 304 Stainless Steel Dissimilar Metals Couple in Deep-Sea Environment. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 517, 145753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Huang, H.; Huang, G. Galvanic Corrosion Behavior between ADC12 Aluminum Alloy and Copper in 3.5 Wt% NaCl Solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 927, 116984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, S.; Peng, Z.; Li, R.; Wang, B. Galvanic Corrosion Behavior of AZ31 Mg Alloy Coupled with Mild Steel: Effect of Coatings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7745–7755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndukwe, A.I.; Nwadirichi, B.; Okolo, C.; Tom-Okoro, M.; Medupin, R.; Uche, R.; Arukalam, I.; Onuoha, C.; Egole, C.; Okorafor, O.; et al. Corrosion Control in Metals: A Review on Sustainable Approach Using Nanotechnology. Zastita Mater. 2025, 66, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindha, T.; Rathinam, R.; Dheenadhayalan, S.; Sivakumar, R. Nanocomposite Coatings in Corrosion Protection Applications: An Overview. Orient. J. Chem. 2021, 37, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O.; Gabatel, L.; Bellani, S.; Barberis, F.; Bonaccorso, F.; Cole, I.; Roche, S. 2D Hexagonal Boron Nitride-Based Anticorrosion Coatings. J. Phys. Mater. 2025, 8, 042002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtela, M.; Samardžija, M.; Bujak, M.; Stojanović, I.; Bojanić, K.; Ljubek, G. Investigation of Corrosion Resistance of Epoxy Coatings Reinforced with Graphene Oxide and Aluminium Nanoparticle. Rud. Geol. Naft. Zb. 2025, 40, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.-Y.; Hao, Y.; Wu, Y.-H.; Zhao, W.-J.; Huang, L.-F. Corrosion Resistance of Ultrathin Two-Dimensional Coatings: First-Principles Calculations towards In-Depth Mechanism Understanding and Precise Material Design. Metals 2021, 11, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.A.; Yao, C.-W.; Lian, I.; Zhou, J.; Jao, M.; Huang, Y.-C. Enhancement of Corrosion Resistance of a Hot-Dip Galvanized Steel by Superhydrophobic Top Coating. MRS Commun. 2022, 12, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, M.; Bi, H.; Dam-Johansen, K. Advanced Materials for Smart Protective Coatings: Unleashing the Potential of Metal/Covalent Organic Frameworks, 2D Nanomaterials and Carbonaceous Structures. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 323, 103055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Kakooei, S. Container-Based Smart Nanocoatings for Corrosion Protection. In Corrosion Protection at the Nanoscale; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 403–421. ISBN 978-0-12-819359-4. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, P.B.; Assad, M.A.; Ismail, M. Inhibitor-Encapsulated Smart Nanocontainers for the Controlled Release of Corrosion Inhibitors. In Corrosion Protection at the Nanoscale; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 91–105. ISBN 978-0-12-819359-4. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, B.; Zheng, Z.; Michailids, M.; Fleck, N.; Bilton, M.; Song, Y.; Li, G.; Shchukin, D. Mussel-Inspired Self-Healing Coatings Based on Polydopamine-Coated Nanocontainers for Corrosion Protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 10283–10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Park, S.; Chelliah, R.; Yeon, S.-J.; Barathikannan, K.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Jeong, Y.-J.; Rubab, M.; Oh, D.H. Emerging Trends in Smart Self-Healing Coatings: A Focus on Micro/Nanocontainer Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Protection. Coatings 2024, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, R.; Shao, Z.; Chen, L.; Wei, W.; Dong, S.; Wang, H. Synergistic Effect of 8-HQ@CeO2 for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance of Self-Healing Polyurethane Coating for Corrosion Protection of Mild Steel. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 186, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.; Stuhr, R.; Vega, J.M.; García-lecina, E.; Grande, H.J.; Leiza, J.R.; Paulis, M. Assessing the Effect of CeO2 Nanoparticles as Corrosion Inhibitor in Hybrid Biobased Waterborne Acrylic Direct to Metal Coating Binders. Polymers 2021, 13, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Lyu, Y.; Li, T.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Xie, X.; Lyu, K.; Shah, S.P. Corrosion Resistance of CeO2-GO/Epoxy Nanocomposite Coating in Simulated Seawater and Concrete Pore Solutions. Polymers 2023, 15, 2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, K.; Du, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Qiu, P. Intrinsic Self-Healable, Corrosion-Resistant Silicone Coating Based on Quadruple Hydrogen-Bonded Supramolecular Polymer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 34100–34112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharieh, A.; Sharifian, A.; Dadkhah, S. Enhanced Long-Term Corrosion Resistance and Self-Healing of Epoxy Coating with HQ-Zn-PA Nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Í.; Simões, S. Strengthening Mechanisms in Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Metal Matrix Composites: A Review. Metals 2021, 11, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinate, S.; Ghassemali, E.; Zanella, C. Strengthening Mechanisms and Wear Behavior of Electrodeposited Ni–SiC Nanocomposite Coatings. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 16632–16648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Guo, X.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Ren, J.; Xue, H.; Tang, F. Strengthening Mechanism of NiCoAl Alloy Induced by Nanotwin under Hall-Petch Effect. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 255, 108478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Zheng, H.; Li, Z.; Bai, P.; Ren, L. Preparation and Mechanical Behavior of Silver-Coated Graphene Reinforced Low Modulus Titanium Matrix Composites by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 926, 147944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Gao, Q.; Xue, H.; Tang, F.; La, P.; Guo, X. Grain Boundary Segregation Strengthening Behavior Caused by Carbon Chain Network Formation in Nanocrystalline NiCoAl Alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmanov, E.I.; Gutkin, M.Y.; Wu, Y.; Sha, G.; Valiev, R.Z. Superstrength of Nanostructured Ti Grade 4 with Grain Boundary Segregations. Metals 2025, 15, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chan, K.; Yang, X.-S. Maintaining Grain Boundary Segregation-Induced Strengthening Effect in Extremely Fine Nanograined Metals. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 5493–5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Hua, P.; Huang, K.; Li, Q.; Sun, Q. Grain Boundary and Dislocation Strengthening of Nanocrystalline NiTi for Stable Elastocaloric Cooling. Scr. Mater. 2023, 226, 115227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, M.; Kainz, C.; Dorner, P.; Fellner, S.; Terziyska, V.; Alfreider, M.; Kiener, D. Phase Stability and Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Nanocrystalline PVD CrCu Coatings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Size-Dependent Atomic Strain Localization Mechanism in Nb/Amorphous CuNb Nanolayered Composites. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 205103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Li, H.; Wang, C.; Liang, Y.; Feng, N.; Zhang, N.; Yang, L. Mechanical Properties and Strengthening Mechanism of Ni/Al Nanolaminates: Role of Dislocation Strengthening and Constraint in Soft Layers. Mater. Des. 2023, 226, 111632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, M.; Li, Y.; Wen, M.; Wen, C. Microstructures and Nanomechanical Properties of Nanolaminated Ta/Co Composites and Their Strengthening Mechanisms. Adv. Nanocomposites 2024, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.-R.; Xu, S.; Su, Y.; Beyerlein, I.J. Role of Layer Thickness and Dislocation Distribution in Confined Layer Slip in Nanolaminated Nb. Int. J. Plast. 2022, 152, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, C.; Li, X. Layer-Thickness-Dependent Strengthening–Toughening Mechanisms in Crystalline/Amorphous Nanolaminates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 47377–47384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fu, K.; Li, Y. A Theoretical Modelling of Strengthening Mechanism in Graphene-Metal Nanolayered Composites. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 195, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Shi, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Cao, T.; Xu, S.; Fan, X. Alloy Strengthening toward Improving Mechanical and Tribological Performances of CuxNi100−x/Ta Nano Multilayer Materials. Tribol. Int. 2023, 190, 109039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-L. Effects of Nd and B Contents on Property Evaluation of (CoCrNi)100–B Nd Medium Entropy Alloy Films. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 482, 130707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhong, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ding, J.; Xia, X. Solid Solution Strengthening and Diffusion Behaviors in Mg–Bi and Mg–Al–Bi Alloys via High-Throughput Measurements. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Motlag, M.; Saei, M.; Jin, S.; Rahimi, R.M.; Bahr, D.; Cheng, G.J. Shock Engineering the Additive Manufactured Graphene-Metal Nanocomposite with High Density Nanotwins and Dislocations for Ultra-Stable Mechanical Properties. Acta Mater. 2018, 150, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, O.R.; Khan, S.M.; Patil, D.K.A.; Chin, J. Wear Resistance and Mechanical Properties of Nanocomposite Coatings: Applications in Aerospace Engineering. Nanotechnol. Percept. 2025, 21, 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani, A.; Abdullah, A.; Fallahi Arezoodar, A. Wear Behavior of Metal Matrix Nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 35947–35965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Sahoo, P. Fabrication and Investigation of Abrasive Wear Behavior of AZ31-WC-Graphite Hybrid Nanocomposites. Metals 2022, 12, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, E.; BinAhmed, S.; Keyes, P.; Alberg, C.; Godfreey-Igwe, S.; Haugstad, G.; Xiong, B. Nanoscale Abrasive Wear of Polyethylene: A Novel Approach To Probe Nanoplastic Release at the Single Asperity Level. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13845–13855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skobeleva, N.S.; Parfenov, A.S.; Kopyshev, I.Y.; Volkov, A.V.; Berezina, E.V. Mechanism of Abrasion Reduction in Polydisperse System with Carbon Nanoparticles. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 402, 11006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarey, M.J.G.; Ratwani, C.R.; Xie, K.; Koohgilani, M.; Hadfield, M.; Kamali, A.R.; Abdelkader, A.M. Multifunctional Steel Surface through the Treatment with Graphene and H-BN. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, F.; Yang, K.; Xiong, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, H.; Duan, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, B. Review of Two-Dimensional Nanomaterials in Tribology: Recent Developments, Challenges and Prospects. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 321, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, R.; Yao, J.; Mu, Z.; Gu, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wen, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, K. Contrarian Design of Versatile MoS2-Based Self-Lubrication Film. Small 2025, 21, e08430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, F.; Chen, J.; Alhashmialameer, D.; Wang, S.; Mahmoud, M.H.H.; Mersal, G.A.M.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, G.; et al. Enhanced Mechanical, Thermal, and Tribological Performance of 2D-Laminated Molybdenum Disulfide/RGO Nanohybrid Filling Phenolic Resin Composites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, Q.U.; Wani, M.F.; Sehgal, R.; Singh, M.K. Tribological and Mechanical Characterization of Carbon-Nanostructures Based PEEK Nanocomposites under Extreme Conditions for Advanced Bearings: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Tribol. Int. 2024, 196, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattikuti, S.V.P.; Byon, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Molybdenum Disulfide Nanoflowers and Nanosheets: Nanotribology. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 710462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbitt, N.S.; Curry, J.F.; Babuska, T.F.; Chandross, M. Water Adsorption on MoS2 under Realistic Atmosphere Conditions and Impacts on Tribology. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 4717–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarev, A.; Ponomarev, I.; Muydinov, R.; Polcar, T. Friend or Foe? Revising the Role of Oxygen in the Tribological Performance of Solid Lubricant MoS2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 55051–55061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Shi, Y.; Cui, M.; Ren, S.; Wang, H.; Pu, J. MoS2/WS2 Nanosheet-Based Composite Films Irradiated by Atomic Oxygen: Implications for Lubrication in Space. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 10307–10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuska, T.F.; Curry, J.F.; Thorpe, R.; Chowdhury, M.I.; Strandwitz, N.C.; Krick, B.A. High-Sensitivity Low-Energy Ion Spectroscopy with Sub-Nanometer Depth Resolution Reveals Oxidation Resistance of MoS2 Increases with Film Density and Shear-Induced Nanostructural Modifications of the Surface. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, X. Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Arc Ion Plating NbN-Based Nanocomposite Films. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Dai, X.Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.H.; Zhang, C.S.; Ding, J.C.; Zheng, J. Comparative Study of Plasma Nitriding and Plasma Oxynitriding for Optimal Wear and Corrosion Resistance: Influences of Gas Composition. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, H.; Vargas, G.; Magdaleno, C.; Silva, R. Article: Oxy-Nitriding AISI 304 Stainless Steel by Plasma Electrolytic Surface Saturation to Increase Wear Resistance. Metals 2023, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grützmacher, P.G.; Suarez, S.; Tolosa, A.; Gachot, C.; Song, G.; Wang, B.; Presser, V.; Mücklich, F.; Anasori, B.; Rosenkranz, A. Superior Wear-Resistance of Ti3C2Tx Multilayer Coatings. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 8216–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Divakaran, A.; Kailas, S.V. Fabrication and Tribo Characteristics of In-Situ Polymer-Derived Nano-Ceramic Composites of Al-Mg-Si Alloy. Tribol. Int. 2023, 180, 108272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kong, Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Li, G. Wear and Aging Behavior of Vulcanized Natural Rubber Nanocomposites under High-Speed and High-Load Sliding Wear Conditions. Wear 2022, 498–499, 204341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharin, H.A.; Ghazali, M.J.; Thachnatharen, N.; Ezzah, F.; Walvekar, R.; Khalid, M. Progress in 2D Materials Based Nanolubricants: A Review. FlatChem 2023, 38, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Turner, K.T. Thermal and Mechanical Mechanisms of Polymer Wear at the Nanoscale. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 50004–50011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, S.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Qian, L.; Chen, L. Asynchronous Mechanochemical Atomic Attrition Behavior of Heterogeneous Polysilicon Surface. Wear 2025, 570, 205915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leriche, C.; Pedretti, E.; Kang, D.; Righi, M.C.; Weber, B. Passivation Species Suppress Atom-by-Atom Wear of Micro-Crystalline Diamond. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 55511–55520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiao, C.; Sun, J.; Qian, L.; Chen, L. Graphene Failure under MPa: Nanowear of Step Edges Initiated by Interfacial Mechanochemical Reactions. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 3866–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S. Tribocorrosion of CrN Coatings on Different Steel Substrates. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 484, 130829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Z. Electrochemical and Tribocorrosion Performances of CrMoSiCN Coating on Ti-6Al-4V Titanium Alloy in Artificial Seawater. Corros. Sci. 2020, 165, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Sui, Y.; Lan, J.; Xue, Q. Improvement in the Tribocorrosion Performance of CrCN Coating by Multilayered Design for Marine Protective Application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 528, 147061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod, R.; Veeresh, K.; Basavarajappa, S. Investigation of the Effect of Drilling Induced Delamination and Tool Wear on Residual Strength in Polymer Nanocomposites. FME Trans. 2024, 52, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.M.; Gacem, A.; Kistan, A.; Ashick, R.M.; Rao, L.M.; Rajput, V.S.; Nagabooshanam, N.; Refat, M.S.; Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Christopher, D. Investigation of High-Temperature Wear Behaviour of AA 2618-Nano Si3N4 Composites Using Statistical Techniques. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 3449903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, X. Employing Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for Microscale Investigation of Interfaces and Interactions in Membrane Fouling Processes: New Perspectives and Prospects. Membranes 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Burrows, R.; Kumar, D.; Kloucek, M.B.; Warren, A.D.; Flewitt, P.E.J.; Picco, L.; Payton, O.D.; Martin, T.L. Observation of Stress Corrosion Cracking Using Real-Time in Situ High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy and Correlative Techniques. npj Mater. Degrad. 2021, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.; Burrows, R.; Picco, L.; Payton, O.D.; Martin, T.L. Real-Time and Correlative Imaging of Localised Corrosion Events by High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. Microsc. Microanal. 2022, 28, 2116–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sharma, S.; Pailleret, A.; Brown, B.; Nešić, S. Investigation of Corrosion Inhibitor Adsorption on Mica and Mild Steel Using Electrochemical Atomic Force Microscopy and Molecular Simulations. Corrosion 2022, 78, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Lai, T.; Yin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Yan, H.; Song, H.; Liu, R.; Luo, C.; Hu, Z. In-Situ AFM and Quasi-in-Situ Studies for Localized Corrosion in Mg-9Al-1Fe-(Gd) Alloys under 3.5 Wt.% NaCl Environment. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 1170–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pura, J.L.; Salvo-Comino, C.; García-Cabezón, C.; Rodríguez-Méndez, M.L. Concurrent Study of the Electrochemical Response and the Surface Alterations of Silver Nanowire Modified Electrodes by Means of EC-AFM. The Role of Electrode/Nanomaterial Interaction. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 38, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To-A-Ran, W.; Mastoi, N.R.; Ha, C.Y.; Song, Y.J.; Kim, Y.-J. Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy and Electrochemical Atomic Force Microscopy Investigations of Lithium Nucleation and Growth: Influence of the Electrode Surface Potential. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 7265–7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaman, H.L.; Li, M.; Rose, J.A.; Narasimhan, S.; Xu, X.; Yeh, C.-N.; Jin, N.; Akbashev, A.; Davidoff, I.; Bazant, M.Z.; et al. Two-Stage Growth of Solid Electrolyte Interphase on Copper: Imaging and Quantification by Operando Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 11949–11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malladi, S.R.K.; Ummethala, G.; Jada, R.; Dutta-Gupta, S.; Park, J.; Tavabi, A.; Basak, S.; Hooley, R.; Sun, H.; Pérez-Garza, H.H.; et al. Real-Time Visualisation of Organic Crystal Growth Dynamics during Liquid Reagent Mixing by Liquid Cell Transmission Electron Microscopy. preprint 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, K.; Seo, J.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Kwon, J.-H. Investigating Charge-Induced Transformations of Metal Nanoparticles in a Radically-Inert Liquid: A Liquid-Cell TEM Study. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Schneider, N.M.; Tan, S.F.; Ross, F.M. Temperature Dependent Nanochemistry and Growth Kinetics Using Liquid Cell Transmission Electron Microscopy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 5609–5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnawski, T.; Parlińska-Wojtan, M. Opportunities and Obstacles in LCTEM Nanoimaging—A Review. Chem. Methods 2024, 4, e202300041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shao, Y.-T.; Lu, X.; Yang, Y.; Ko, H.-Y.; DiStasio, R.A.; DiSalvo, F.J.; Muller, D.A.; Abruña, H.D. Elucidating Cathodic Corrosion Mechanisms with Operando Electrochemical Transmission Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 15698–15708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shao, Y.-T.; Jin, J.; Feijóo, J.; Roh, I.; Louisia, S.; Yu, S.; Guzman, M.V.F.; Chen, C.; Muller, D.A.; et al. Operando Electrochemical Liquid-Cell Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (EC-STEM) Studies of Evolving Cu Nanocatalysts for CO2 Electroreduction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 4119–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachraoui, W.; Pauer, R.; Battaglia, C.; Erni, R. Operando Electrochemical Liquid Cell Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy Investigation of the Growth and Evolution of the Mosaic Solid Electrolyte Interphase for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 20434–20444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed, M.N.; Yousif, Q.A.; Bedair, M.A. Study of the Corrosion of Nickel–Chromium Alloy in an Acidic Solution Protected by Nickel Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 29850–29857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattu, V.K.; Obregon, J.; Ebert, W.L.; Indacochea, J.E. Effects of Open Circuit Immersion and Vertex Potential on Potentiodynamic Polarization Scans of Metallic Biomaterials. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, N.; Fillon, A.T.; Renk, O.; Kremmer, T.; Pogatscher, S.; Suter, T.; Schmutz, P. Local Electrochemical Characterization of Active Mg-Fe Materials—From Pure Mg to Mg50-Fe Composites. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.08645. [Google Scholar]

- Gerengi, H.; Cabrini, M.; Solomon, M.M.; Kaya, E. Understanding the Corrosion Behavior of the AZ91D Alloy in Simulated Body Fluid through the Use of Dynamic EIS. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 11929–11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branzoi, F.; Băran, A.; Mihai, M.A.; Praschiv, A. Anticorrosive Effect of New Polymer Composite Coatings on Carbon Steel in Aggressive Environments by Electrochemical Procedures. Coatings 2025, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, Y.H.A.; Rostami, M.; Sari, M.G.; Ramezanzadeh, B. pH-Responsive Anti-Corrosion Activity of Gallic Acid-Intercalated MgAl LDH in Acidic, Neutral, and Alkaline Environments. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, S.A.; Hu, S.; Ghaderi, S.; Ghanbari, A.; Ahmadipour, M.; Pung, S.-Y.; Li, S.; Feilizadeh, M.; Arjmand, M. Amino-Functionalized MXene Nanosheets Doped with Ce(III) as Potent Nanocontainers toward Self-Healing Epoxy Nanocomposite Coating for Corrosion Protection of Mild Steel. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 42074–42093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, J.; Izadi, M.; Bozorg, M. Improvement of Anti-Corrosion Performance of an Epoxy Coating Using Hybrid UiO-66-NH2/Carbon Nanotubes Nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorgami, G.; Arash Haddadi, S.; Okati, M.; Mekonnen, T.H.; Ramezanzadeh, B. In Situ-Polymerized and Nano-Hybridized Ti3C2-MXene with PDA and Zn-MOF Carrying Phosphate/Glutamate Molecules; toward the Development of pH-Stimuli Smart Anti-Corrosion Coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Jiang, C.; Yin, X.; Liu, K.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, X.; Sun, Z. Polyaniline/TiO2/MXene Ternary Composites for Enhancing Corrosion Resistance of Waterborne Epoxy Coatings. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wei, H.; Hao, P.; Li, S.; Zhao, X.; Tang, Y.; Zuo, Y. Study on the Influence of Metal Substrates on Protective Performance of the Coating by EIS. Materials 2024, 17, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Howard, C.B.; Xu, F.; Salvato, D.; Bawane, K.K.; Murray, D.J.; Frazer, D.M.; Anderson, S.T.; Yao, T.; Yeo, S.; et al. Microstructural and Micromechanical Characterization of Cr Diffusion Barrier in ATR Irradiated U-10Zr Metallic Fuel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 599, 155231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bai, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H. Mechanical Properties of Silicon Nitride in Different Morphologies: In Situ Experimental Analysis of Bulk and Whisker Structures. Materials 2024, 17, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Song, Y.; Liang, T.; Ma, D.; Wang, J.; Xie, J. Interfacial Microstructure of Dual-Scale SiCp/A356 Composites Investigated by in Situ TEM Tensile Testing. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1004, 175892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginov, P.A.; Zaitsev, A.A.; Sidorenko, D.A.; Eganova, E.M.; Levashov, E.A. Interfacial Interaction and Evaluation of Bonding Strength between Diamond and CoCrFeNi(Cu,Ti) High-Entropy Alloys. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 151, 111849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeij, T.; Sharma, A.; Steinbach, D.; Lou, J.; Michler, J.; Maeder, X. In Situ Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction Tensile Testing. Scr. Mater. 2025, 261, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutor, R.K.; Azeemullah, M.; Cao, Q.P.; Wang, X.D.; Zhang, D.X.; Jiang, J.Z. Microstructure and Properties of a Co-Free Fe50Mn27Ni10Cr13 High Entropy Alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 851, 156842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yu, X.; Tang, D.; Yuan, R.; Sun, H. Microstructural Evolution and Strengthening Mechanisms in CrxMnFeNi High-Entropy Alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 2114–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeij, T.; Verstijnen, J.A.C.; Ramirez Y Cantador, T.J.J.; Blaysat, B.; Neggers, J.; Hoefnagels, J.P.M. A Nanomechanical Testing Framework Yielding Front&Rear-Sided, High-Resolution, Microstructure-Correlated SEM-DIC Strain Fields. Exp. Mech. 2022, 62, 1625–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, M.; Han, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Hou, Y.; Lu, Y. Direct Measurement of Tensile Mechanical Properties of Few-Layer Hexagonal Boron Nitride (h-BN). J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 224301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, L.; Su, Z.; Xiong, Y. Application of Nanoindentation Technique in Mechanical Characterization of Organic Matter in Shale: Attentive Issues, Test Protocol, and Technological Prospect. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 113, 204966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanpée, S.; Nysten, B.; Chevalier, J.; Pardoen, T. Nanoindentation Analysis of Transcrystalline Layers in Model Carbon Fiber-Reinforced PEEK Composite. Polym. Test. 2025, 143, 108714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, I.; Sheridan, R.J.; Zauscher, S.; Brinson, L.C. Pushing AFM to the Boundaries: Interphase Mechanical Property Measurements near a Rigid Body. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrriques, A.E.; Howard, S.; Timsina, R.; Khadka, N.K.; Hoover, A.N.; Ray, A.E.; Ding, L.; Onwumelu, C.; Nordeng, S.; Mainali, L.; et al. Atomic Force Microscopy Cantilever-Based Nanoindentation: Mechanical Property Measurements at the Nanoscale in Air and Fluid. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, e64497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontomaris, S.V.; Malamou, A.; Stylianou, A. Simplifying Data Processing in AFM Nanoindentation Experiments on Thin Samples. Eng 2025, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An Improved Technique for Determining Hardness and Elastic Modulus Using Load and Displacement Sensing Indentation Experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dziadkowiec, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Peng, P.; Renard, F. Combining Atomic Force Microscopy and Nanoindentation Helps Characterizing In-Situ Mechanical Properties of Organic Matter in Shale. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 281, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, L.R.L.; Ferreira, J.P.S.; Parente, M.P.L. Deep Learning Regressors of Surface Properties from Atomic Force Microscopy Nanoindentations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xi, Y.; He, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Tu, S. Chemical Short-Range Order Strengthening Mechanism in CoCrNi Medium-Entropy Alloy under Nanoindentation. Scr. Mater. 2022, 209, 114364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Yang, L.; Hu, Y.; Liang, X.; Hua, M.; Zhang, J. Strengthening Mechanism of CoCrNiMox High Entropy Alloys by High-Throughput Nanoindentation Mapping Technique. Intermetallics 2021, 135, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoro, A.M.; Lephuthing, S.S.; Rasiwela, L.; Olubambi, P.A. Nondestructive Measurement of the Mechanical Properties of Graphene Nanoplatelets Reinforced Nickel Aluminium Bronze Composites. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhal, A.; Agrawal, P.; Haridas, R.S.; Gaddam, S.; Sharma, A.; Parganiha, D.; Mishra, R.S.; Kawanaka, H.; Matsushita, S.; Yasuda, Y.; et al. High-Throughput Investigation of Multiscale Deformation Mechanism in Additively Manufactured Ni Superalloy. Metals 2023, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alroy, R.J.; Seekala, H.; Phani, P.S.; Sivakumar, G. Role of High-Speed Nanoindentation Mapping to Assess the Structure-Performance Correlation of HVAF-Sprayed Cr3C2-25NiCr Coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 481, 130652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.P.; Ranganathan, R. Tensile and Viscoelastic Behavior in Nacre-Inspired Nanocomposites: A Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Study. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyel, J.-P.; Hajjar, A.; Debastiani, R.; Antouly, K.; Atli, A. Impact of Viscoelasticity on the Stiffness of Polymer Nanocomposites: Insights from Experimental and Micromechanical Model Approaches. Polymer 2024, 309, 127443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanparast, R.; Rafiee, R. A 3D Viscoelastic–Viscoplastic Behavior of Carbon Nanotube-reinforced Polymers: Constitutive Model and Experimental Characterization. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 6425–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Avilés, M.-D.; Pamies, R.; Carrión-Vilches, F.-J.; Sanes, J.; Bermúdez, M.-D. Extruded PLA Nanocomposites Modified by Graphene Oxide and Ionic Liquid. Polymers 2021, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madarvoni, S.; Ps Rama, S. Dynamic Mechanical Behaviour of Graphene, Hexagonal Boron Nitride Reinforced Carbon-Kevlar, Hybrid Fabric-Based Epoxy Nanocomposites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 09673911221107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, H.; Gurumurthy, G.D.; Yogananda, G.S.; Mahesh, T.S.; Bommegowda, K.B. Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Graphene and Carbon Fabric-reinforced Epoxy Nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 5281–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Yazik, M.H.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Jawaid, M.; Abu Talib, A.R.; Mazlan, N.; Md Shah, A.U.; Safri, S.N.A. Effect of Nanofiller Content on Dynamic Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube and Montmorillonite Nanoclay Filler Hybrid Shape Memory Epoxy Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, Q.U.; Wani, M.F.; Sehgal, R.; Singh, M.K. Mechanical and Viscoelastic Characterization of Al2O3 Based Polymer Nanocomposites: An Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Approach. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 239, 112955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.-W.; Lian, I. Nanoscale Insights into the Mechanical and Tribological Properties of a Nanocomposite Coating. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Bor, B.; Plunkett, A.; Domènech, B.; Maier-Kiener, V.; Giuntini, D. Nanoindentation Creep of Supercrystalline Nanocomposites. Mater. Des. 2023, 231, 112000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Miller, J.; Weber, W.J.; Bei, H.; Zhang, Y. Deformation Mechanisms in Single Crystal Ni-Based Concentrated Solid Solution Alloys by Nanoindentation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 856, 143685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, K.; Yang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Yang, J.; Guo, Y.; Mao, G.; Yang, L.; Nie, F.; et al. Nanoindentation Size Effects of Mechanical and Creep Performance in Ni-Based Superalloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 39, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zan, Z.; Zhao, L.; Qin, F. Nanoindentation Elastoplastic and Creep Behaviors of Sintered Nano-Silver Doped with Nickel-Modified Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Filler. J. Electron. Mater. 2024, 53, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.-W.; Lian, I.; Zhou, J.; Bernazzani, P.; Jao, M. The Elevated-Temperature Nano-Mechanical Properties of a PDMS–Silica-Based Superhydrophobic Nanocomposite Coating. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnbrough, E.; Aspinall, J.; Pasta, M.; Armstrong, D.E.J. Elastic and Plastic Mechanical Properties of Lithium Measured by Nanoindentation. Mater. Des. 2023, 233, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Dong, X.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y. Simulation and Experimental Study on Stress Relaxation Response of Polycrystalline γ-TiAl Alloy under Nanoindentation Based on Molecular Dynamics. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, H.; Merle, B. Novel Nanoindentation Strain Rate Sweep Method for Continuously Investigating the Strain Rate Sensitivity of Materials at the Nanoscale. Mater. Des. 2023, 236, 112471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomes, S.; Adachi, N.; Wakeda, M.; Ohmura, T. Probing Pre-Serration Deformation in Zr-Based Bulk Metallic Glass via Nanoindentation Testing. Scr. Mater. 2023, 237, 115713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Hu, Y.; Ding, S.; Wu, W.; Xia, R. Fatigue Responses of Metallic Glass-based Stochastic Network Nanomaterial: Superior Strain-hardening Ability. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 47, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmahl, M.; Müller, C.; Meinke, R.; Alcantara, E.G.A.; Hangen, U.D.; Fleck, C. Cyclic Nanoindentation for Local High Cycle Fatigue Investigations: A Methodological Approach Accounting for Thermal Drift. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2023, 25, 2201676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yan, J. Towards Understanding the Mechanism of Vibration-Assisted Cutting of Monocrystalline Silicon by Cyclic Nanoindentation. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 311, 117797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owhal, A.; Belwanshi, V.; Roy, T.; Goel, S. Strain Softening Observed during Nanoindentation of Equimolar-Ratio Co–Mn–Fe–Cr–Ni High Entropy Alloy. J. Micromanufacturing 2024, 25165984241228094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Yu, J.; Gao, Z. Cyclic Degradation Mechanisms of Al0.3CoCrFeNi High-Entropy Alloy under Different Loading Rates. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 107640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalev, A.I.; Vakhrushev, V.O.; Beake, B.D.; Konovalov, E.P.; Wainstein, D.L.; Dmitrievskii, S.A.; Fox-Rabinovich, G.S.; Veldhuis, S. Damage Accumulation Phenomena in Multilayer (TiAlCrSiY)N/(TiAlCr)N, Monolayer (TiAlCrSiY)N Coatings and Silicon upon Deformation by Cyclic Nanoindentation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübler, D.; Winkler, K.; Riedel, R.; Kamrani, S.; Fleck, C. Cyclic Deformation Behavior of Mg–SiC Nanocomposites on the Macroscale and Nanoscale. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2022, 45, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M.; Shimpi, N.G. Mechanical Response of Silver/Polyvinyl Alcohol Thin Film: From One-Step and Cyclic Nanoindentation. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2022, 5, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, S.; Kacprzyńska-Gołacka, J.; Smolik, J.; Wieciński, P. Mechanical Properties of Cu+CuO Coatings Determined by Nanoindentation and Laugier Model. Materials 2025, 18, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolik, J.; Sowa, S.; Kacprzyńska-Gołacka, J.; Piasek, A. Evaluation of the Fracture Toughness KIc for Selected Magnetron Sputtering Coatings by Using the Laugier Model. Materials 2022, 15, 9061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautham, S.; Sasmal, S. Nano-Scale Fracture Toughness of Fly Ash Incorporated Hydrating Cementitious Composites Using Experimental Nanoindentation Technique. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 117, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günen, A.; Makuch, N.; Altınay, Y.; Çarboğa, C.; Dal, S.; Karaca, Y. Determination of Fracture Toughness of Boride Layers Grown on Co1.21Cr1.82Fe1.44Mn1.32Ni1.12Al0.08B0.01 High Entropy Alloy by Nanoindentation. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 36410–36424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapitskaya, V.A.; Kuznetsova, T.A.; Chizhik, S.A.; Rogachev, A.A. Determination of Fracture Toughness of the Thin Diamond-like Coatings by Nanoindentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Belarus Phys. Tech. Ser. 2024, 68, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Peng, Y. Characterizing the Micro-Fracture in Quasi-Brittle Rock Using Nanoindentation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 308, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhaee-Pour, A. Deep Learning for Characterizing Fracture Toughness from the Nanoindentation Image of a Complex Heterogeneous Medium. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 135, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beake, B.D.; Vishnyakov, V.M.; Zhang, H.; Goodes, S.R.; Rahmati, A.T. Statistically Distributed Nano-Scratch Testing—A Novel Method for Simulating Abrasive Wear. Wear 2025, 571, 205860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Cheenepalli, N.; Lee, H.; Ahn, B. Microstructure and Nanoscratch Behavior of Spark-Plasma-Sintered Ti-V-Al-Nb-Hf High-Entropy Alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3781–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gain, A.K.; Li, Z. Exploring the Deformation Mechanisms and Mechanical Properties of Fused Silica through Nanoindentation and Ramp-Nanoscratching. Wear 2025, 571, 205812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssel, F.; Huang, W.; Yan, J. Investigation of Failure Modes and Material Structural Responses of Nanographite Coatings on Single-Crystal Silicon by Nanoscratching. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. On the Deformation Mechanism and Dislocations Evolution in Monocrystalline Silicon under Ramp Nanoscratching. Tribol. Int. 2024, 193, 109395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beake, B.D.; Vishnyakov, V.M.; Goodes, S.R.; Rahmati, A.T. Statistically Distributed Nano-Scratch Testing of AlFeMnNb, AlFeMnNi, and TiN/Si3N4 Thin Films on Silicon. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2024, 42, 013104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilsnack, E.; Zawischa, M.; Makowski, S.; Zimmermann, M.; Leyens, C. Low Cycle Fatigue of Doped Tetrahedral Amorphous Carbon Coatings by Repetitive Micro Scratch Tests. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 482, 130687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D. Investigation of Cutting Depth and Contact Area in Nanoindenter Scratching. Precis. Eng. 2024, 85, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, H. The Effects of the Angle between the Indenter Edge and the Scratch Direction on the Scratch Characteristics of Ti–6Al–4V Alloy. Wear 2024, 556–557, 205507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Zhou, P.; Goel, S. Microscopic Stress Analysis of Nanoscratch Induced Sub-Surface Defects in a Single-Crystal Silicon Wafer. Precis. Eng. 2023, 82, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zeng, Q. Friction and Wear in Nanoscratching of Single Crystals: Effect of Adhesion and Plasticity. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennewitz, R. Friction Force Microscopy. In Fundamentals of Friction and Wear on the Nanoscale; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dašić, M.; Almog, R.; Agmon, L.; Yehezkel, S.; Halfin, T.; Jopp, J.; Ya’akobovitz, A.; Berkovich, R.; Stanković, I. Role of Trapped Molecules at Sliding Contacts in Lattice-Resolved Friction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 44249–44260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, R.; Inoue, S.; Nikaido, K.; Nakajima, K.; Hasegawa, T. Friction Force Mapping of Molecular Ordering and Mesoscopic Phase Transformations in Layered-Crystalline Organic Semiconductor Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 39701–39707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Nguyen, P.L.; Vlassiouk, I.V.; Choi, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, S. Unveiling the Mechanism of Surface Corrugation Formation on a Quasi Free-Standing Bi-Layer Graphene via Experimental and Modeling Investigations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 644, 158749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Y.; Gnecco, E.; Chu, J. Shear Anisotropy Domains on Graphene Revealed by In-Plane Elastic Imaging. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 27317–27326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.-P.; Kim, H.-J.; Chung, K.-H. Long-Term Wear Characteristics of Single-Layer h-BN, MoS 2, and Graphene. Tribol. Int. 2026, 213, 111059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Egberts, P. Triboelectrification and Unique Frictional Characteristics of Germanium-Based Nanofilms. Small 2024, 20, e2309862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksaray, G.; Mert, M.E.; Doğru Mert, B. DFT Approach in Corrosion Research. Osman. Korkut Ata Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2025, 8, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhou, W.; Ji, Y.; Dong, C. Applications of Density Functional Theory to Corrosion and Corrosion Prevention of Metals: A Review. Mater. Genome Eng. Adv. 2025, 3, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, K.; Chen, P.; Yin, L.; Yang, J. Multiscale Simulation of Nanowear-Resistant Coatings. Materials 2025, 18, 3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Pei, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, R.; Cheng, X.; Ma, L. A Review of Trends in Corrosion-Resistant Structural Steels Research—From Theoretical Simulation to Data-Driven Directions. Materials 2023, 16, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, C.; Neils, A.; Lesko, J.; Post, N. Machine Learning Accelerated Discovery of Corrosion-Resistant High-Entropy Alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 237, 112925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, T.; Tang, Q.; Wang, M.; Ying, T.; Zhu, H.; Zeng, X. High-Throughput Calculations Combining Machine Learning to Investigate the Corrosion Properties of Binary Mg Alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 1406–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Berkeley, G.; Polifrone, K.; Xu, W. An Atomistic Study of Deformation Mechanisms in Metal Matrix Nanocomposite Materials. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, K.-Q.; Kadapa, C. Multiscale Modeling for the Statics of Nanostructures. In Nano Scaled Structural Problems; Chakraverty, S., Ed.; AIP Publishing LLCMelville: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2-1–2-38. ISBN 978-0-7354-2283-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Jin, Y.; Hua, A.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, J. Multiscale Theories and Applications: From Microstructure Design to Macroscopic Assessment for Carbon Nanotubes Networks. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoei, A.R.; Seddighian, M.R.; Sameti, A.R. Machine Learning-Based Multiscale Framework for Mechanical Behavior of Nano-Crystalline Structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 265, 108897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winetrout, J.J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Gaber, L.; Unnikrishnan, V.; Varshney, V.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Heinz, H. Prediction of Carbon Nanostructure Mechanical Properties and the Role of Defects Using Machine Learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2415068122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champa-Bujaico, E.; Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Lomas Redondo, A.; Garcia-Diaz, P. Optimization of Mechanical Properties of Multiscale Hybrid Polymer Nanocomposites: A Combination of Experimental and Machine Learning Techniques. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 269, 111099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, M.B.; Rao, R.N.; Ismail, S.; Gupta, M.; Prasad, P.S. Tribo-Informatics Approach to Predict Wear and Friction Coefficient of Mg/Si3N4 Composites Using Machine Learning Techniques. Tribol. Int. 2024, 196, 109696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talapatra, A.; Datta, D. Experimental and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Based Investigation to Understand Tribological Performance of Graphene Reinforced Thermoplastic Polyurethane (Gr/TPU) Nanocomposites. Tribol. Int. 2024, 196, 109703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.B.; Sahu, S.K. Taguchi and Machine Learning Integration for Tribological Analysis of Polyurethane/Nanodiamond Nanocomposites. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2025, 13506501251362067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherwar, A.; Ahirwar, A.; Pathak, V.K. Dry Sliding Tribological Characteristics Evaluation and Prediction of TiB2-CDA/Al6061 Hybrid Composites Exercising Machine Learning Methods. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherwar, A.; Ahirwar, A.; Pathak, V.K. Triboinformatic Analysis and Prediction of B4C and Granite Powder Filled Al 6082 Composites Using Machine Learning Regression Models. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, M.; Drenchev, L.; Petkov, V. Fabrication, Experimental Investigation and Prediction of Wear Behavior of Open-Cell AlSi10Mg-SiC Composite Materials. Metals 2023, 13, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Qiao, H.; Zhao, J. Temperature-dependent Tribological and Interfacial Properties of Perfluoroelastomer Nanocomposites Modified with Graphene Nanosheets Functionalized through Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, S925–S942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etsuyankpa, M.B.; Hassan, I.; Musa, S.T.; Mathew, J.T.; Shaba, E.Y.; Andrew, A.; Muhammad, A.I.; Muhammad, K.T.; Jibrin, N.A.; Abubakar, M.K.; et al. Comprehensive Review of Recent Advances in Nanoparticle-Based Corrosion Inhibition Approaches. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2024, 28, 2269–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, M.; Lancia, M.; Zheng, C.; Re, V.; Castelvetro, V.; Guo, S.; Viaroli, S. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) Nanomechanical Characterization of Micro- and Nanoplastics to Support Environmental Investigations in Groundwater. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doniger, W.H.; Couet, A.; Sridharan, K. Potentiodynamic Polarization of Pure Metals and Alloys in Molten LiF-NaF-KF (FLiNaK) Using the K/K + Dynamic Reference Electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 071502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, W.; Hu, J.; Fu, H. Anti-Corrosion Epoxy/Modified Graphene Oxide/Glass Fiber Composite Coating with Dual Physical Barrier Network. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 167, 106823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gorair, A.S.; Saleh, M.G.A.; Alotaibi, M.T.; Al-Juaid, S.S.; Abdallah, M.; Wanees, S.A.E. Potentiometric and Polarization Studies on the Oxide Film Repair and Retardation of Pitting Corrosion on Indium in an Alkaline Aqueous Solution Utilizing Some Triazole Compounds. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023, 158, 111497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbaraki, Z.D.; Azadi, M.; Hafazeh, A. Electrochemical Characteristics of Nano-Structure TiCN Coatings on the Tool Steel Deposited by PACVD in Various Solutions. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batakliev, T.; Ivanov, E.; Georgiev, V.; Angelov, V.; Ahuir-Torres, J.I.; Harvey, D.M.; Kotsilkova, R. New Insights in the Nanomechanical Study of Carbon-Containing Nanocomposite Materials Based on High-Density Polyethylene. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendaoued, A.; Salhi, R. A Comprehensive Analysis of the Structural, Textural, and Nanomechanical Properties of Sol–Gel Synthesized TiO2, Al2O3, and SiO2 Nanoparticles. Euro Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2025, 10, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Sharma, R.K.; Sehgal, R. An Experimental Investigation on Nanomechanical and Nanotribological Behavior of Tantalum Nitride Coating Deposited on Ti6Al7Nb Alloy. Tribol. Int. 2024, 194, 109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iteney, H.; Cornelius, T.W.; Thomas, O.; Amodeo, J. Influence of Surface Roughness on the Deformation of Gold Nanoparticles under Compression. Acta Mater. 2024, 281, 120317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, L.; Xi, S.; Li, C.; Su, Y.; Yang, L. Synergistic Effect of Interface and Agglomeration on Young’s Modulus of Graphene-Polymer Nanocomposites. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2024, 292, 112716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, M.; Payandehpeyman, J.; Hedayatian, M. Agglomeration and Interphase-Influenced Effective Elastic Properties of Metal/Graphene Nanocomposites: A Developed Mean-Field Model. Compos. Struct. 2024, 329, 117762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rościszewska, M.; Shimabukuro, M.; Ronowska, A.; Mielewczyk-Gryń, A.; Zieliński, A.; Hanawa, T. Enhanced Bioactivity and Mechanical Properties of Silicon-Infused Titanium Oxide Coatings Formed by Micro-Arc Oxidation on Selective Laser Melted Ti13Nb13Zr Alloy. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 43979–43993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Nie, M.; Li, B.; Wu, B.; Zheng, A.; Yin, K.; Sun, L. Real-Time Quantitative Electromechanical Characterization of Nanomaterials Based on Integrated MEMS Device. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 22592–22599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.K.; Mahur, P.; Manimunda, P.; Mishra, K. Recent Advances in Nanomechanical Measurements and Their Application for Pharmaceutical Crystals. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 4848–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiener, D.; Wurmshuber, M.; Alfreider, M.; Schaffar, G.J.K.; Maier-Kiener, V. Recent Advances in Nanomechanical and in Situ Testing Techniques: Towards Extreme Conditions. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2023, 27, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, R.; Bhattacharyya, K.; Bhattacharyya, A.S. Stress Distribution Variations during Nanoindentation Failure of Hard Coatings on Silicon Substrates. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2023, 6, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, S. Controlling Strain Localization in Thin Films with Nanoindenter Tip Sharpness. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontomaris, S.V.; Stylianou, A.; Chliveros, G.; Malamou, A. A New Elementary Method for Determining the Tip Radius and Young’s Modulus in AFM Spherical Indentations. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Yu, Q.; Yin, Z.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lou, H.; Shen, B.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, Q. Spatial Resolution Limit for Nanoindentation Mapping on Metallic Glasses. Materials 2022, 15, 6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Gao, K.; Cai, W. The Study on the Substrate Effect in the Nanoindentation Experiment of the Hybrid Material. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5031865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Nanoindentation Study on Helium-Irradiated Graphene–Aluminum Composite: Indentation Size Effect, Creep Behavior, and Their Implications for Coating–Substrate Systems. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnert, C.; Durst, K. Nanoindentation Creep Testing: Advantages and Limitations of the Constant Contact Pressure Method. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoli, V.; Kamnis, S.; Delibasis, K.; Georgatis, E.; Kiape, S.; Karantzalis, A.E. The Advanced Assessment of Nanoindentation-Based Mechanical Properties of a Refractory MoTaNbWV High-Entropy Alloy: Metallurgical Considerations and Extensive Variable Correlation Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Polycarpou, A.A. Nanomechanical and Nanoscratch Behavior of Oxides Formed on Inconel 617 at 950 °C. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoque, M.A.; Yao, C.-W. Nanoscale Characterization of Nanomaterial-Based Systems: Mechanisms, Experimental Methods, and Challenges in Probing Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231824

Hoque MA, Yao C-W. Nanoscale Characterization of Nanomaterial-Based Systems: Mechanisms, Experimental Methods, and Challenges in Probing Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231824

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoque, Md Ashraful, and Chun-Wei Yao. 2025. "Nanoscale Characterization of Nanomaterial-Based Systems: Mechanisms, Experimental Methods, and Challenges in Probing Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231824

APA StyleHoque, M. A., & Yao, C.-W. (2025). Nanoscale Characterization of Nanomaterial-Based Systems: Mechanisms, Experimental Methods, and Challenges in Probing Corrosion, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1824. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231824