Classification of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Classification of SOFC

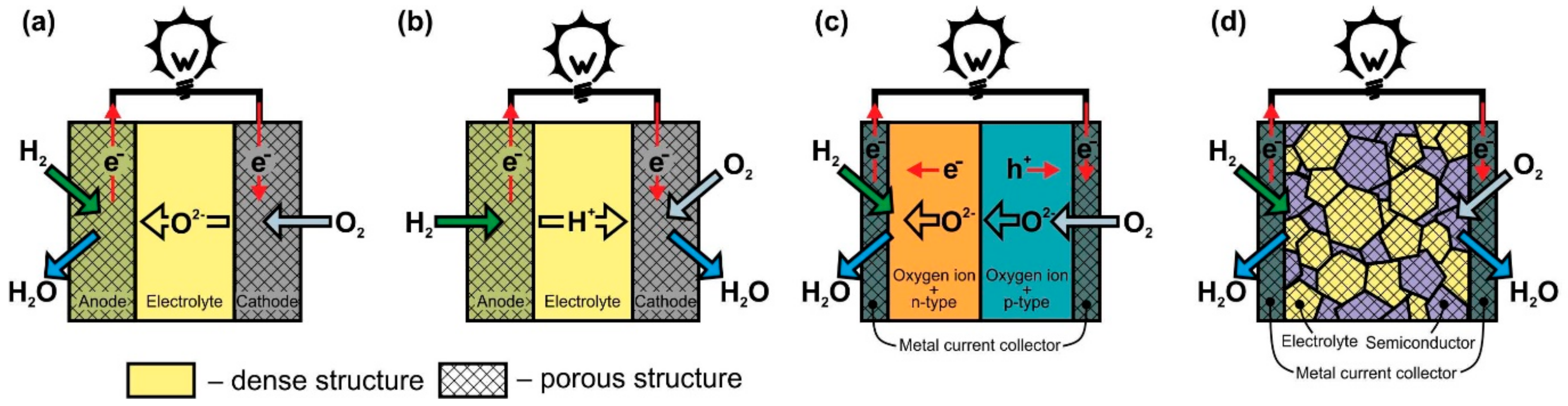

2.1. Classification according to the Presence/Absence of Electrolyte

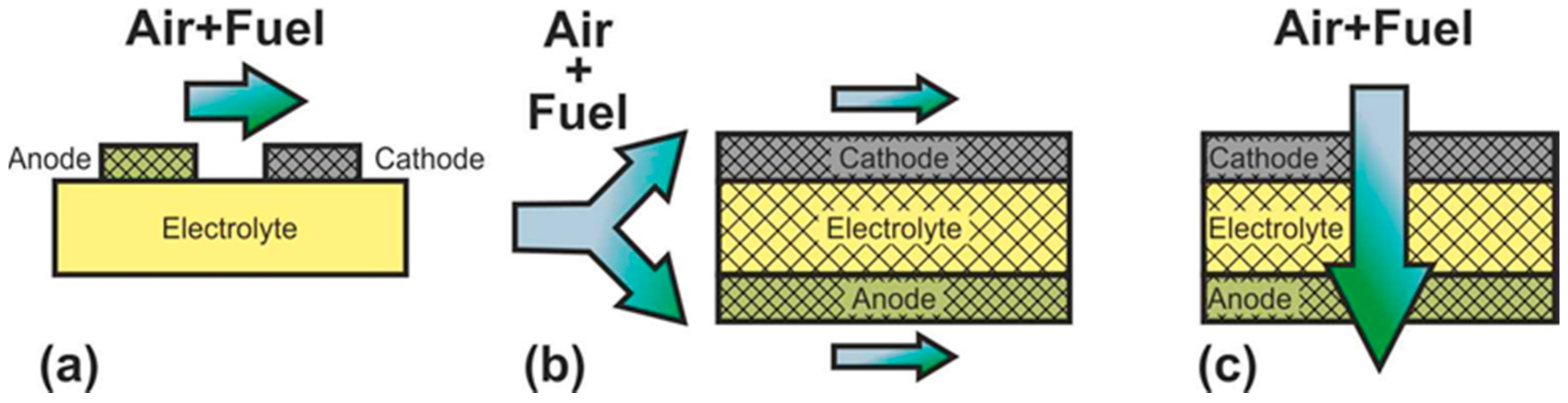

2.2. Classification according to the Gas Spaces Separation

2.3. Classification according to Operating Temperature

2.4. Classification according to Support Types

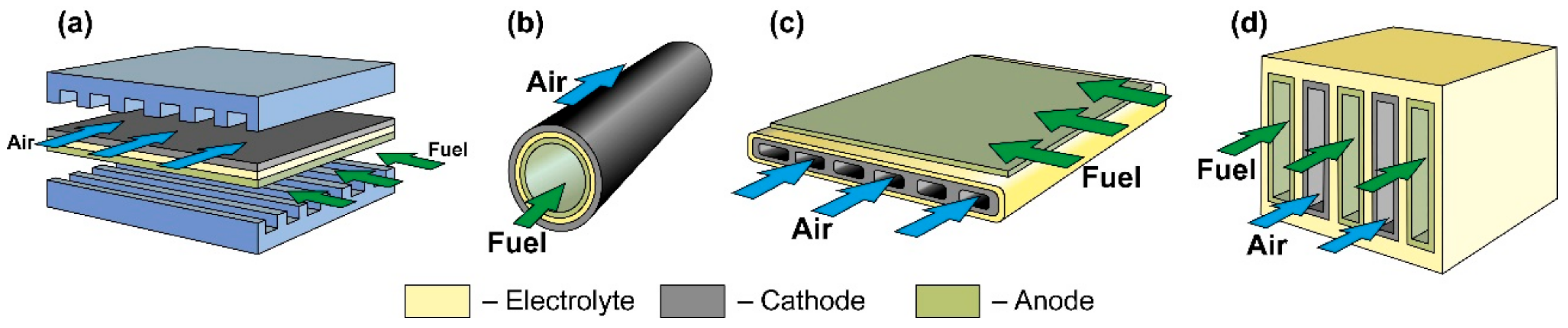

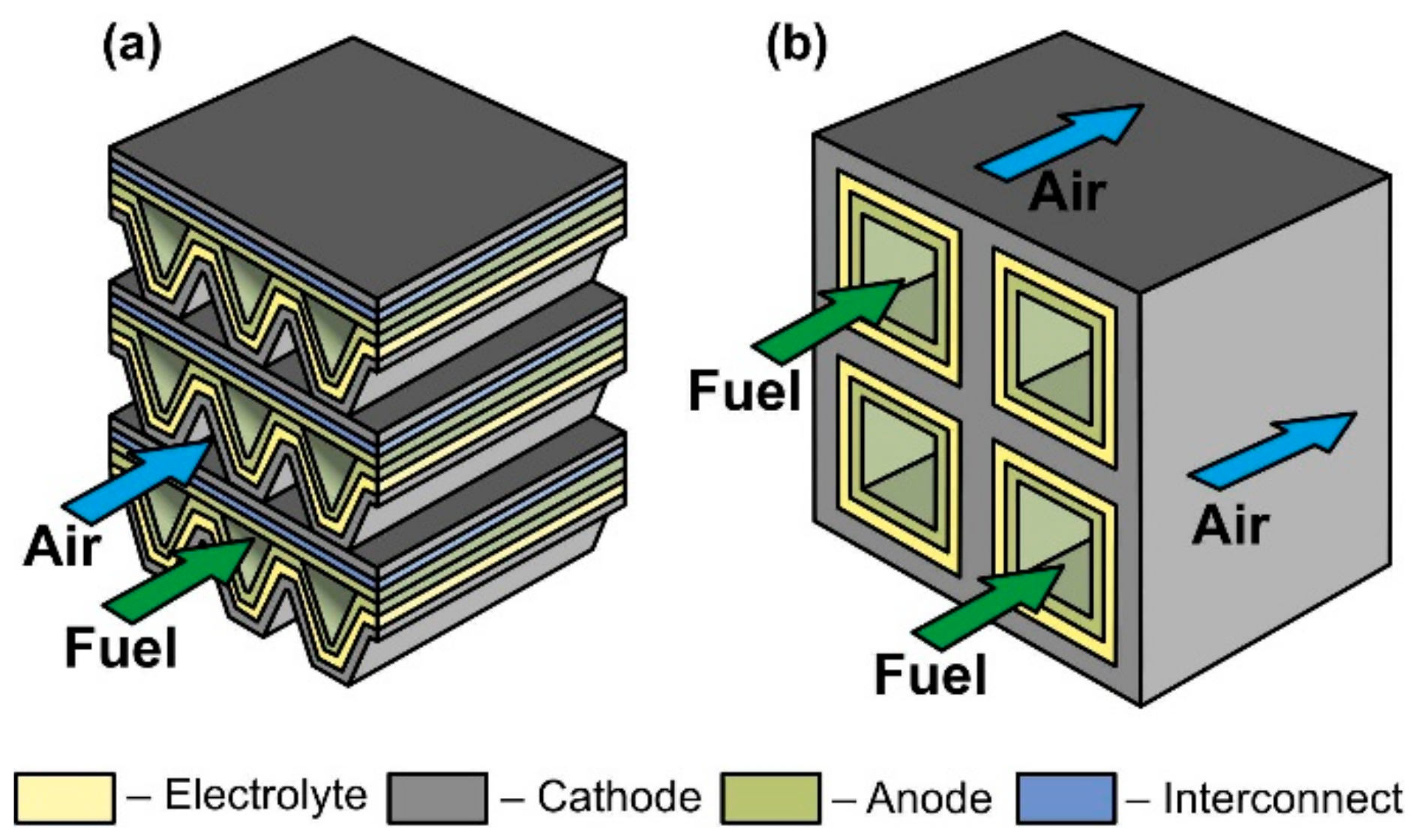

2.5. Classification according to Cell Design

3. Systematization of SOFC

4. Separate Designs and Concepts of SOFC

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirubakaran, A.; Jain, S.; Nema, R.N. A review on fuel cell technologies and power electronic interface. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2009, 13, 2430–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, F.; Hussain, M.A.; Mokhlis, H. A comprehensive review and technical guideline for optimal design and operations of fuel cell-based cogeneration systems. Processes 2019, 7, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perfil’ev, M.V.; Demin, A.K.; Kuzin, B.L.; Lipilin, A.S. Vysokotemperaturnyj Jelektroliz Gazov; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1988; 232p, ISBN 5-02-001399-4. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, N.Q. Ceramic fuel cells. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1993, 76, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, N.Q. Solid oxide fuel cell technology—Features and applications. Solid State Ion. 2004, 174, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: From Materials to System Modeling; Ni, M.; Zhao, T.S. (Eds.) UK RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; 523p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Napporn, T.W. Single-chamber solid oxide fuel cell technology—From its origins to today’s state of the art. Energies 2010, 3, 57–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Raza, R.; Fan, L.; Sun, C. (Eds.) Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: From Electrolyte-Based to Electrolyte-Free Devices; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2020; 488p, ISBN 978-3-527-81278-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bello, I.T.; Zhai, S.; Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Yu, N.; Ni, M. Scientometric review of proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 37406–37428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Abdalla, A.M.; Jamain, S.N.B.; Zaini, J.H.; Azad, A.K. A review on proton conducting electrolytes for clean energy and intermediate temperature-solid oxide fuel cells. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2017, 79, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.C.; Kendall, K. (Eds.) High Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells: Fundamentals, Design and Applications; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2003; 405p, ISBN 1856173879. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, W.H.; Samson, A.J.; Thangadurai, V. Trends in electrode development for next generation solid oxide fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 17913–17932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fergus, J.W. Electrolytes for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2006, 162, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Li, L. A review of zirconia-based solid electrolytes. Ionics 2016, 22, 2249–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, N.; Tanwar, K.; Suman, R.; Kumar, D.; Upadhyay, S.; Parkash, O. A brief review on ceria based solid electrolytes for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 781, 984–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, B.S.; Kumar, S.S.; Aruna, S.T. Properties and development of Ni/YSZ as an anode material in solid oxide fuel cell: A review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2014, 36, 149–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.H.; Rahman, H.A.; Somalu, M.R. Review: Enhancement of composite anode materials for low-temperature solid oxide fuels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 30692–30704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, Z.; Mori, T.; Jiang, S.P. Development of nickel based cermet anode materials in solid oxide fuel cells—Now and future. Mater. Rep. Energy 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.P. Development of lanthanum strontium manganite perovskite cathode materials of solid oxide fuel cells: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 6799–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.P. Development of lanthanum strontium cobalt ferrite perovskite electrodes of solid oxide fuel cells—A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7448–7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curia, M.; Silva, E.R.; Furtado, J.G.M.; Ferraz, H.C.; Secchi, A.R. Anodes for SOFC: Review of material selection, interface and electrochemical phenomena. Quim. Nova 2021, 44, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, W.; Ding, D.; Liu, M.; Ciucci, F.; Tade, M.; Shao, Z. Advances in cathode materials for solid oxide fuel cells: Complex oxides without alkaline earth metal elements. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.; Mayeshiba, T.; Booske, J.; Morgan, D. Material discovery and design principles for stable, high activity perovskite cathodes for solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, P.; Li, W.; Zhao, H.; Wu, C.; Zhao, L.; Dong, B.; Wang, S. Review on Ruddlesden–Popper perovskites as cathode for solid oxide fuel cells. J. Phys. Mater. 2021, 4, 022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.Z.; Ahmad, S.H.; Chen, R.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Hazan, R.; Baharuddin, N.A. Review on recent advancement in cathode material for lower and intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 47, 1103–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Zhu, B.; Su, P.-C.; He, C. Nanomaterials and technologies for low temperature solid oxide fuel cells: Recent advances, challenges and opportunities. Nano Energy 2018, 45, 148–176. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S.; Sharma, B.; Park, D.-H.; Myung, J. Materials and nano-structural processes for use in solid oxide fuel cells: A review. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2020, 57, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Janga, I.; Kima, S.; Kima, C.; Yoon, H.; Song, T. Enhancement of oxygen reduction reaction through coating a nano-web-structured La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ thin-film as a cathode/electrolyte interfacial layer for lowering the operating temperature of solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2018, 392, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pavzderin, N.B.; Solovyev, A.A.; Nikonov, A.V.; Shipilova, A.V.; Rabotkin, S.V.; Semenov, V.A.; Grenaderov, A.S.; Oskomov, K.V. Formation of a dense La(Sr)Fe(Ga)O3 interlayer at the electrolyte/porous cathode interface by magnetron sputtering and its effect on the cathode characteristics. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2021, 57, 519–525. [Google Scholar]

- Develos-Bagarinao, K.; de Vero, J.; Kishimoto, H.; Ishiyama, T.; Yamaji, K.; Horita, T.; Yokokawa, H. Multilayered LSC and GDC: An approach for designing cathode materials with superior oxygen exchange properties for solid oxide fuel cells. Nano Energy 2018, 52, 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Fan, H.; Han, M. La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3-δ nanoparticles modified Ni-based anode for direct methane-fueled SOFCs. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 2250–2255. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, K.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, K.; He, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yoo, S.; Zhao, B.; Yuan, W.; Liu, M.; et al. Enhanced Cr-tolerance of an SOFC cathode by an efficient electro-catalyst coating. Nano Energy 2020, 72, 104704. [Google Scholar]

- Venancio, S.A.; Sarruf, B.J.M.; Gomes, G.G.; de Miranda, P.E.V. Multifunctional macroporous solid oxide fuel cell anode with active nanosized ceramic electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 5501–5511. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Liu, X.J. Recent development of SOFC metallic interconnect. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, J.C.W.; Muchtar, A.; Somalu, M.R.; Ghazali, M.J. Metallic interconnects for solid oxide fuel cell: A review on protective coating and deposition techniques. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9219–9229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, E.; Pergolesi, D.; Traversa, E. Materials challenges toward proton-conducting oxide fuel cells: A critical review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4355–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Amoroso, J.; Tong, J.; Brinkman, K.S. Review: Recent progress in low-temperature proton-conducting ceramics. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 9291–9312. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Ghosh, S.; Aich, S.; Roy, B. Low temperature solid oxide electrolytes (LT-SOE): A review. J. Power Sources 2017, 339, 103–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.H. Progress in proton-conducting oxides as electrolytes for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells: From materials to devices. Energy Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 984–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Su, C.; Shi, H.; Zhu, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Toward reducing the operation temperature of solid oxide fuel cells: Our past 15 years of efforts in cathode development. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15169–15194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Raza, R.; Qin, H.; Liu, Q.; Fan, L. Fuel cells based on electrolyte and non-electrolyte separators. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2986–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wu, X.; Cai, Y.; Ji, Y.; Yaqub, A.; Zhu, B. Design, fabrication and characterization of a double layer solid oxide fuel cell (DLFC). J. Power Sources 2016, 332, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.P.; Huang, X.J.; Chen, L.Q. A practice of single layer solid oxide fuel cell. Ionics 2000, 6, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Raza, R.; Qin, H.; Fan, L. A fuel cell with a single component functioning simultaneously as the electrodes and electrolyte. Electrochem. Commun. 2011, 13, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Jiang, Z.; Fan, L.; Singh, M.; Wang, F.; Raza, R.; Sajid, M.; Wang, J.; Kim, J.S.; Zhu, B. Junction and energy band on novel semiconductor-based fuel cells. iScience 2021, 24, 102191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Tian, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y. Single-layer fuel cell based on a composite of Ce0.8Sm0.2O2−δ–Na2CO3 and a mixed ionic and electronic conductor Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6−δ. J. Power Sources 2014, 249, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Lund, P.; Raza, R.; Patakangas, J.; Huang, Q.-A.; Fan, L.; Singh, M. A new energy conversion technology based on nano-redox and nano-device processes. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Lund, P.D.; Raza, R.; Ma, Y.; Fan, L.; Afzal, M.; Patakangas, J.; He, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, W.; et al. Schottky junction effect on high performance fuel cells based on nanocomposite materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Mi, Y.; Xia, C.; Wang, B.; Kim, J.-S.; Lund, P.; Li, T. A nanoscale perspective on solid oxide and semiconductor membrane fuel cells: Materials and technology. Energy Mater. 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar]

- Yano, M.; Tomita, A.; Sano, M.; Hibino, T. Recent advances in single-chamber solid oxide fuel cells: A review. Solid State Ion. 2007, 177, 3351–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques-Bedard, X.; Napporn, T.W.; Roberge, R.; Meunier, M. Coplanar electrodes design for a single-chamber SOFC. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, B305–B309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamvar, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Rezaei, M. Effect of catalyst layer configuration on single chamber solid oxide fuel cell performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 100, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bessaa, M.; Aguado, S.; Steil, M.C.; Rembelski, D.; Rieu, M.; Viricelle, J.-P.; Benameur, N.; Guizard, C.; Tardivat, C.; et al. An all porous solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC): A bridging technology between dual and single chamber SOFCs. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 2119–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.M.; Largiller, G.; Guizard, C.; Tardivat, C.; Farrusseng, D. Coke-free operation of an all porous solid oxide fuel cell (AP-SOFC) used as an O2 supply device. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2684–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, M.; Suganuma, S.; Watanabe, M. Electrochemical power generation directly from combustion flame of gases, liquids, and solids. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, A1402–A1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cai, N.; Cao, T.; Zhang, J. (Eds.) High-Temperature Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage: Fundamentals and Applications; CRC Press: London, UK, 2018; 223p, ISBN 9780367889838. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, M.K.; Lu, K. Glass-based seals for solid oxide fuel and electrolyzer cells—A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2010, 67, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Walia, T. Review on silicate and borosilicate-based glass sealants and their interaction with components of solid oxide fuel cell. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 20559–20582. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, I.J. On the single chamber solid oxide fuel cells. Power Sources 2008, 175, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedon, A.; Viricelle, J.P.; Rieu, M.; Mascotto, S.; Glisenti, A. Single chamber Solid Oxide Fuel Cells selective electrodes: A real chance with brownmillerite-based nanocomposites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021, 46, 14735–14747. [Google Scholar]

- Vogler, M.; Barzan, D.; Kronemayer, H.; Schulz, C.; Horiuchi, M.; Suganuma, S.; Tokutake, Y.; Warnatz, J.; Bessler, W.G. Direct-flame solid-oxide fuel cell (DFFC): A thermally self-sustained, air self-breathing, hydrocarbon-operated SOFC System in a simple, no-chamber setup. ECS Trans. 2007, 7, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, N.H. Fuel cells. In Current Technology Challenges and Future Research Needs; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlnds, 2013; 685p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rij, L.N.; Le, J.; van Landschoot, R.C.; Schoonman, J.A. A novel Ni-CERMET electrode based on a proton conducting electrolyte. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, E.; D’Epifanio, A.; Sanna, S.; Bartolomeo, E.D.; Balestrino, G.; Licoccia, S.; Traversa, E. A novel single chamber solid oxide fuel cell based on chemically stable thin films of Y-doped BaZrO3 proton conducting electrolyte. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Milcarek, R.J.; Zeng, P.; Ahn, J. Flame-assisted fuel cells running methane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 4659–4665. [Google Scholar]

- Milcarek, R.J.; Wang, K.; Falkenstein-Smith, R.L.; Ahn, J. Micro-tubular flame-assisted fuel cells for micro-combined heat and power systems. J. Power Sources 2016, 306, 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Milcarek, R.J.; Ahn, J. Micro-tubular flame-assisted fuel cells running methane, propane and butane: On soot, efficiency and power density. Energy 2019, 169, 776–782. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Cao, T.; Zeng, H.; Cai, N.; Ye, X.; Wang, S. A flame fuel cell stack powered by a porous media combustor. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 22595–22603. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, B.C.H. Material science and engineering: The enabling technology for the commercialisation of fuel cell systems. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, D.J.L.; Atkinson, A.; Brandon, N.P.; Skinner, S.J. Intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G. (Ed.) Intermediate Temperature Solid Oxide Fuel Cells; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlnds, 2020; 516p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.L.; Damo, U.M.; Turan, A.; Sanchez, D. Hybrid Systems Based on Solid Oxide Fuel Cells; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; 325p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Ivers-Tiffee, E.J. Materials and concepts for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) in stationary and mobile applications. Power Sour. 2004, 127, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsman, E.D.; Lee, K.T. Lowering the temperature of solid oxide fuel cells. Science 2011, 334, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timurkutluk, B.; Timurkutluk, C.; Mat, M.D.; Kaplan, Y. A review on cell/stack designs for high performance solid oxide fuel cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, F.; Xiong, C.; Jia, L.; Li, J. A review on anode on-cell catalyst reforming layer for direct methane solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 25208–25224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Tong, J.; Shang, M.; Nikodemski, S.; Sanders, M.; Ricote, S.; Almansoori, A.; O’Hayre, R. Readily processed protonic ceramic fuel cells with high performance at low temperatures. Science 2015, 349, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Rainwater, B.H.; Bai, Y. Electrochemical properties of micro-tubular intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cell with novel asymmetric structure based on BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3-δ proton conducting electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 16887–16897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zeng, P.; Ahn, J. High performance direct flame fuel cell using a propane flame. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 3431–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Luo, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L.; Shi, J. The study of portable direct-flame solid oxide fuel cell (DF-SOFC) stack with butane fuel. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2014, 42, 1135–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.C.; Ying, A.S. Metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells operated in direct-flame configuration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 24426–24434. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, A.; Iwanschitz, B.; Weissen, U.; Denzler, R.; Haberstock, D.; Nerlich, V.; Sfeir, J.; Schuler, A. Status of Hexis SOFC stack development and the Galileo 1000 N micro-CHP system. ECS Trans. 2009, 25, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ghuman, J.S.; Kumar, R. Bloom Energy for producing electricity. Int. J. Power Syst. Oper. Energy Manag. 2014, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Han, Y.J. Fabrication of electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells using a tape casting process. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 128, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.C.; Strakey, J.P.; Surdoval, W.A.; Wilson, L.C. Solid oxide fuel cell technology development in the U.S. Solid State Ion. 2006, 177, 2039–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, V.P. Versa Power’s SOFC could scale to MW for SECA, and work in transport hybrids. Fuel Cells Bull. 2007, 2007, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.-S.; Lee, T.; Choi, J.H.; Park, T.-S.; Oh, J.-M.; Kim, C.-Y. Fabrication and demonstration of 1kW class SOFC stack and system for residential power generation application. J. Fuel Cell Sci. Technol. 2009, 6, 021008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santori, G.; Brunetti, E.; Polonara, F. Experimental characterization of an anode-supported tubular SOFC generator fueled with hydrogen, including a principal component analysis and a multi-linear regression. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 8435–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harboe, S.; Schreiber, A.; Margaritis, N.; Blum, L.; Guillon, O.; Menzler, N.H. Manufacturing cost model for planar 5 kWel SOFC stacks at Forschungszentrum Julich. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8015–8030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsipis, E.V.; Kharton, V.V. Electrode materials and reaction mechanisms in solid oxide fuel cells: A brief review. II. Electrochemical behavior vs. materials science aspects. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2008, 12, 1367–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Singhal, S.C. Cathode-supported tubular solid oxide fuel cell technology: A critical review. J. Power Sources 2013, 237, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Kim, B.-H.; Du, Y.; Xu, Q.; Ahn, B.-G. Ceria catalyst for inert-substrate supported tubular solid oxide fuel cells running on methane fuel. J. Power Sources 2016, 314, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, F.J.; Day, M.J.; Brandon, N.P.; Pashley, M.N.; Cassidy, M. SOFC technology development at Rolls-Royce. J. Power Sources 2000, 86, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Ando, Y.; Kabata, T.; Nishiura, M.; Tomida, K.; Matake, N. Extremely high-efficiency thermal power system-solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) triple combined-cycle system. Mitsubishi Heavy Ind. Tech. Rev. 2011, 48, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, V.V. Recent developments in metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2017, 6, e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.C. Progress in metal-supported solid oxide electrolysis cells: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 24203–24218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, W. Chemically stable yttrium and tin co-doped barium zirconate electrolyte for next generation high performance proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.K.; Abdalla, A.M.; Afif, A.; Azad, A.; Afroze, S.; Idris, A.C.; Park, J.-Y.; Saqib, M.; Radenahmad, N.; Hossain, S.; et al. Improved mechanical strength, proton conductivity and power density in an ‘all-protonic’ ceramic fuel cell at intermediate temperature. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19382. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.H.; Kim, S.K.; Nam, J.T.; Park, J.S. Fabrication of an electrolyte-supported protonic ceramic fuel cell with nano-sized powders of Ni-composite anode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stange, M.; Stefan, E.; Denonville, C.; Larring, Y.; Rørvik, P.M.; Haugsrud, R. Development of novel metal-supported proton ceramic electrolyser cell with thin film BZY15-Ni electrode and BZY15 electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 13454–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Byrne, C.; Tucker, M.C. Assessment of co-sintering as a fabrication approach for metal-supported proton-conducting solid oxide cells. Solid State Ion. 2019, 332, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, M.C. Personal power using metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells operated in a camping stove flame. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2018, 43, 8991–8998. [Google Scholar]

- Sayan, Y.; Venkatesan, V.; Guk, E.; Wu, H.; Kim, J.-S. Single-step fabrication of an anode supported planar single-chamber solid oxide fuel cell. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2018, 15, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Lü, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, B.; Guo, X.; Wu, P. Effect of the angle between gas flow direction and electrode on single-chamber SOFC stacks. J. Solid State Electr. 2019, 23, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Wu, P.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Ding, L. Performance of a linear array solid oxide fuel cell micro-stack operated in single-chamber conditions. Ionics 2020, 26, 6217–6224. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, I.; Kim, J.-S.; Venkatesan, V.; Ranaweera, M. Fabrication and evaluation of a novel wavy single chamber solid oxide fuel cell via in-situ monitoring of curvature evolution. Appl. Energy 2017, 195, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Kamvar, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Steinberger-Wilckens, R. The numerical investigation of a planar single chamber solid oxide fuel cell performance with a focus on the support types. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 7077–7087. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, S.; Jak, M.J.G.; Schoonman, J.; Riess, I. Supported mixed-gas fuel cells. Solid State Ion. 2002, 149, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsilp, D.; Rechberger, J.; Neubauer, R.; Bischof, C. Metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells with exceptionally high power density for range extender systems. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lin, J.; Liu, T.; Wu, H.; Xia, C.; Chen, C.; Zhan, Z. Tailoring the pore structure of cathode supports for improving. J. Electroceram. 2018, 40, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Cho, G.Y.; Yu, W.; Su, P.C.; Lee, M.H.; Cha, S.W. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition of nanoscale yttria-stabilized zirconia electrolyte for solid oxide fuel cells with porous substrate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 2998–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Gou, Y.; Qiao, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, K. Recent progress of tubular solid oxide fuel cell: From materials to applications. J. Power Sources 2020, 477, 228693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, V.V.; Lipilin, A.S.; Kotov, Y.A.; Khrustov, V.R.; Shkerin, S.N.; Paranin, S.N.; Spirin, A.V.; Kaygorodov, A.S. Formation of a thin-layer electrolyte for SOFC by magnetic pulse compaction of tapes cast of nanopowders. J. Power Sources 2006, 159, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yang, Z.; Han, M. Fabrication of metal-supported tubular solid oxide fuel cell by phase-inversion method and in situ reduction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 10935–10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.H.; Park, J.L.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.J.; Song, R.H.; Shin, D.R. Fabrication and operation of a 1 kW class anode-supported flat tubular SOFC stack. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 9687–9692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Sammes, N.M.; Song, K.H.; Kim, T.; Chung, J.S. Monolithic flat tubular types of solid oxide fuel cells with integrated electrode and gas channels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, U.; Kim, D.W.; Yun, U.J.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.J.; Song, R.H.; Kim, G.; Lim, T.H. Effect of cathode geometry on the electrochemical performance of flat tubular segmented-in-series (SIS) solid oxide fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 6207–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Iltaf, A.; Ishfaq, H.A.; Khan, F.N.; Tanveer, W.H.; Song, R.H.; Mehran, M.T.; Saleem, M.; Hussain, A.; Masaud, Z. Flat-tubular solid oxide fuel cells and stacks: A review. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2021, 9, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M. Functionally graded cathodes fabricated by sol-gel/slurry coating for honeycomb SOFCs. Solid State Ionics 2005, 176, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Shimizu, S.; Suzuki, T.; Fujishiro, Y.; Awano, M. Fabrication and evaluation of a novel cathode-supported honeycomb SOFC stack. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 2577–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Morales, J.C.; Marrero-Lopez, D.; Pena-Martinez, J.; Canales-Vazquez, J.; Road, J.J.; Segarrad, M.; Savvina, S.N.; Núnez, P. Performance of a novel type of electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cell with honeycomb structure. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S.; Nakajima, H.; Kitahara, T. Enhancement of fuel transfer in anode-supported honeycomb solid oxide fuel cells. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 745, 032082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, A.; Bieberle-Hutter, A.; Rupp, J.L.M.; Gauckler, L.J. Review on microfabricated micro-solid oxide fuel cell membranes. J. Power Sources 2009, 194, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Chang, I.; Cho, G.Y.; Park, J.; Yu, W.; Tanveer, W.H.; Cha, S.W. Thin film solid oxide fuel cells operating below 600 °C: A Review. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf-Green Technol. 2018, 5, 441–453. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.D.; Chang, I.; Su., P.C. Thin-film solid oxide fuel cells. In Materials for Energy, 1st ed.; Zhang, S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 239–283. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.; Kim, Y.-B.; Gür, T.M.; Park, J.; Prinz, F.B. 3-D nanostructured bilayer solid oxide fuel cell with 1.3 W/cm2 at 450 °C. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 4551–4555. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.D.; Liu, K.Y.; Su, P.C. A functional micro-solid oxide fuel cell with 10 nm-thick freestanding electrolyte. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 18414–18419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.P.; Lovett, A.J.; Chalklen, T.; Baiutti, F.; Tarancón, A.; Wang, X.; Ding, J.; Wang, H.; Kar-Narayan, S.; Acosta, M.; et al. Route to high-performance micro-solid oxide fuel cells on metallic substrates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 4117–4125. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Su, P.C.; Park, Y.I.; Saito, Y.; Prinz, F.B. Thin-film solid oxide fuel cells on porous nickel substrates with multistage nanohole array. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A554–A559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Lee, J.; Cho, G.Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Cha, S.W.; Bae, J. Scalable fabrication process of thin-film solid oxide fuel cells with an anode functional layer design and a sputtered electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 33980–33992. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, G.Y.; Yu, W.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.; Tanveer, W.H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Cha, S.W. Effects of nanoscale PEALD YSZ interlayer for AAO based thin film solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf-Green Technol. 2020, 7, 423–430. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J.; Park, B.H.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, Y.; Bae, H.; Choi, G.M. Micro solid oxide fuel cell fabricated on porous stainless steel: A new strategy for enhanced thermal cycling ability. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reolon, R.P.; Sanna, S.; Xu, Y.; Lee, I.; Bergmann, C.P.; Prydsa, N.; Esposito, V. Effects of accelerated degradation on metal supported thin film-based solid oxide fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 7887–7896. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S.; Lee, S.; Jeong, W.; Ryu, S.; Yu, W.; Lee, Y.H.; Cho, G.Y.; Cha, S.W. Nanoporous nickel thin film anode optimization for low-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 36445–36453. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Lim, Y.; Lee, S.; Pandiyan, A.; Cho, G.; Cha, S.W. Low-temperature, high-performance thin-film solid oxide fuel cells with tailored nano-column structures of a sputtered Ni anode. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 41, 21668–21679. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Ren, H.; Wu, E.A.; Fullerton, E.E.; Meng, Y.S.; Minh, N.Q. All-sputtered, superior power density thin-film solid oxide fuel cells with a novel nanofibrous ceramic cathode. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, K. Progress in microtubular solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2010, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jin, Y.; Li, D.; Xiong, Y. A review on recent advances in micro-tubular solid oxide fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2021, 506, 230135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.S.; Thompson, G.J.; Kendall, K. Micro-tubular solid oxide fuel cells and stacks. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, V.; Griesser, S.; Buchinger, G.; Olabi, A.G.; Cordiner, S.; Meissner, D. Review of the micro-tubular solid oxide fuel cell Part I. Stack design issues and research activities. J. Power Sources 2009, 193, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, S.M.; Othman, M.H.D.; Rahman, M.A.; Jaafar, J.; Ismail, A.F. Anode supported micro-tubular SOFC fabricated with mixed particle size electrolyte via phase-inversion technique. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9188–9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikonov, A.V.; Spirin, A.V.; Lipilin, A.S.; Khrustov, V.R.; Paranin, S.N. Fabrication of microtubular solid oxide fuel cells by film compaction and co-sintering. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2018, 54, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, W.S.; Lin, P.; Wang, S.F. Characteristics of electrolyte supported micro-tubular solid oxide fuel cells with GDC-ScSZ bilayer electrolyte. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 17267–17274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yang, N.; Gong, X.; Yin, Y.; Ma, Z.-F.; Tan, X.; Shao, Z.; Liu, S. Novel cathode-supported hollow fibers for light weight micro-tubular solid oxide fuel cells with an active cathode functional layer. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, H.; Shimada, H.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yamaguchi, T. Effect of anode thickness on polarization resistance for metal-supported microtubular solid oxide fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, F243–F247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayat, N.; Panthi, D.; Du, Y. Inert substrate-supported microtubular solid oxide fuel cells based on highly porous ceramic by low-temperature co-sintering. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, M.; Chao, C.C.; An, J.; Jung, H.J.; Gur, T.M.; Prinz, F.B. Nanotubular array solid oxide fuel cell. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Decent, S.P.; Loghin, D.; Kendall, K. Mixed-reactant, micro-tubular solid oxide fuel cells: An experimental study. J. Power Sources 2009, 193, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Lee, H.-W.; Kim, B.-K.; Son, J.-W.; Yoon, K.J.; Kim, H.; Shin, D.; Ji, H.-I.; Lee, J.-H. A 5×5 cm2 protonic ceramic fuel cell with a power density of 1.3 W cm–2 at 600 °C. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Xing, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S. Fabrication and performance of anode-supported proton conducting solid oxide fuel cells based on BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3-δ electrolyte by multi-layer aqueous-based co-tape casting. J. Power Sources 2021, 506, 229922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; O’Hayre, R.; Sullivan, N.P. High performance tubular protonic ceramic fuel cells via highly-scalable extrusion process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 27784–27792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifi, A.R.; Sandhu, N.K.; Etsell, T.H.; Luo, J.L.; Sarkar, P. Fabrication and characterization of a tubular ceramic fuel cell based on BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3-d proton conducting electrolyte. J. Power Sources 2017, 341, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Su, P.-C. Proton-conducting micro-solid oxide fuel cells with improved cathode reactions by a nanoscale thin film gadolinium-doped ceria interlayer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22369. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, T.; Lin, Y.; Chen, F. Fabrication of microtubular solid oxide fuel cells using sulfur-free polymer binder via a phase inversion method. J. Power Sources 2015, 290, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Rainwater, B.H.; Bai, Y. High performance of anode supported BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3-δ proton-conducting electrolyte micro-tubular cells with asymmetric structure for IT-SOFCs. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 844, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Morales, J.C.; Marrero-Lopez, D.; Canales-Vazquez, J.; Irvine, J.T.S. Symmetric and reversible solid oxide fuel cells. RSC Adv. 2011, 1, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Wang, W.; Liu, M.; Tade, M.O.; Shao, Z. Progress and prospects in symmetrical solid oxide fuel cells with two identical electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Qi, H.; Tang, S.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Cheng, M.; Shao, Z. A highly active and stable hybrid oxygen electrode for reversible solid oxide cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021, 46, 36012–36022. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, M.B.; Chen, M.; Frandsen, H.L.; Graves, C.; Hansen, J.B.; Hansen, K.V.; Hauch, A.; Jacobsen, T.; Jensen, S.H.; Skafte, T.L.; et al. Reversible solid-oxide cells for clean and sustainable energy. Clean Energy 2019, 3, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.R.; Bosio, B. Operating principles, performance and technology readiness level of reversible solid oxide cells. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SOFC Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| O-SOFC | Well-studied There are industrial devices Potential for internal reforming | Complexity of fabrication Limited selection of materials Low conductivity electrolyte High operating temperatures result in higher thermomechanical stresses and more significant degradation |

| H-SOFC | Higher conductive electrolyte Low operating temperatures suggest less thermomechanical stress and less degradation No fuel dilution with reaction products (H2O) | More research on electrolyte and electrode materials are required Complexity of fabrication Internal reforming is questionable |

| DLFC | Simplicity of fabrication The problem of thermomechanical matching of cell materials is alleviated Wide selection of materials | Poorly studied No internal reforming |

| SLFC | Simplicity of fabrication No problem with thermomechanical matching of cell materials Wide selection of materials | Poorly studied Internal reforming is questionable |

| SOFC Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| DC-SOFC | Well-studied There are industrial devices High efficiency High level of fuel utilization Fire and explosion safety | Complexity of fabrication Matching of thermal expansion of cell materials are required Slow start up |

| SC-SOFC | Simplicity of fabrication Simplified use of hydrocarbons as fuel High resistance to thermomechanical stress | More selective electrodes are required Low efficiency Low level of fuel utilization Flammable and explosive Coking of electrodes |

| DF-SOFC | Simplicity of fabrication Simplified use of hydrocarbons as fuel Potential for quick start up | More selective electrodes are required Low efficiency Low level of fuel utilization High thermomechanical stress Coking of electrodes |

| SOFC Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Self-supporting | ||

| ES SOFC | Relatively strong structural support from dense electrolyte Less susceptible to failure due to anode reoxidation (Ni/YSZ anode) and cathode reduction (LSM cathode) | Higher resistance due to low electrolyte conductivity Higher operating temperatures required to minimize electrolyte ohmic losses |

| AS SOFC | Highly conductive anode Lower operating temperature via use of thin electrolytes | Potential anode reoxidation Mass transport limitation due to thick anodes |

| CS SOFC | No oxidation issues but potential cathode reduction Lower operating temperature via use of thin electrolyte | Lower conductivity Mass transport limitation due to thick cathodes |

| External-supporting | ||

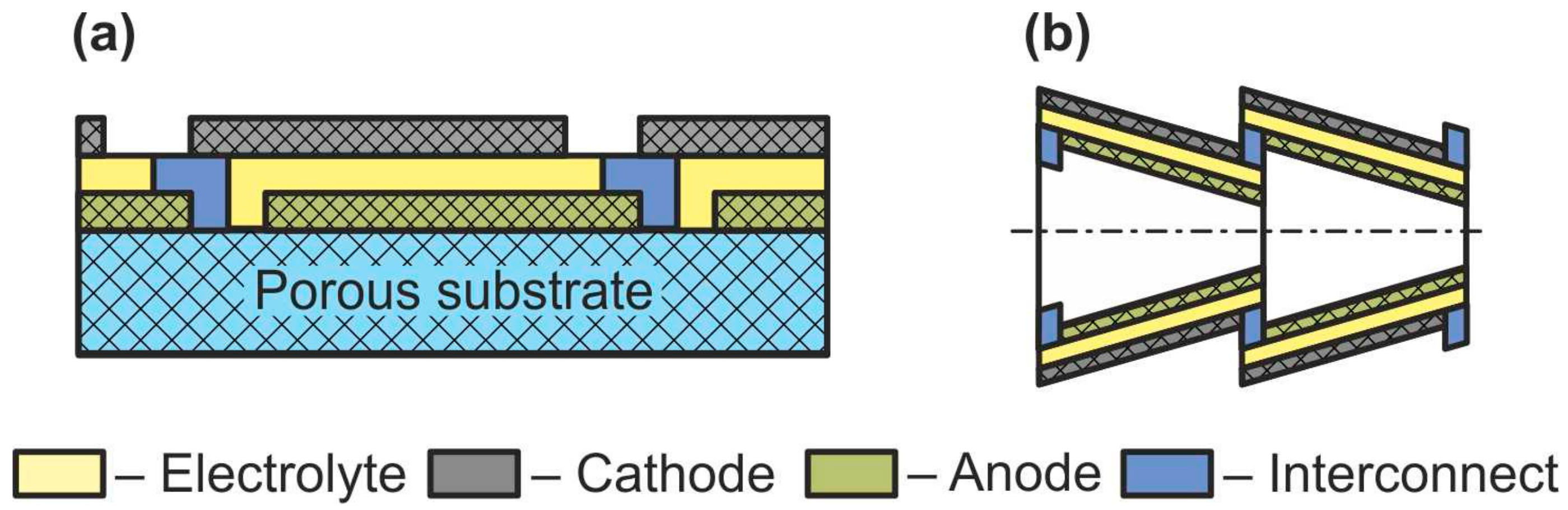

| SS SOFC | Thin cell components for lower operating temperature Potential for use of non-cell material for support to improve properties | Increased complexity due to addition of new materials Possibility of formation of discontinuous layers on a porous substrate |

| MS SOFC | Thin cell components for lower operating temperature Stronger structures from metallic interconnects | Interconnect oxidation Flowfield design limitation due to cell support requirement |

| SOFC Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Planar | High power density Simplicity of stack assembly | Low resistivity of thermomechanical stress Difficulties with sealing |

| Tubular | The resistivity of thermomechanical stress Sealing is simpler than that of planar SOFC | Low power density High internal resistance |

| Flat-tube | The resistivity of thermomechanical stress Simplicity of stack assembly | Complexity of fabrication of single cell High internal resistance |

| Monolithic | Sufficiently high power density High thermomechanical strength High durability | Complexity of fabrication Difficulties with the formation of the current contacts Difficulties with sealing |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuterbekov, K.A.; Nikonov, A.V.; Bekmyrza, K.Z.; Pavzderin, N.B.; Kabyshev, A.M.; Kubenova, M.M.; Kabdrakhimova, G.D.; Aidarbekov, N. Classification of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12071059

Kuterbekov KA, Nikonov AV, Bekmyrza KZ, Pavzderin NB, Kabyshev AM, Kubenova MM, Kabdrakhimova GD, Aidarbekov N. Classification of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Nanomaterials. 2022; 12(7):1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12071059

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuterbekov, Kairat A., Alexey V. Nikonov, Kenzhebatyr Zh. Bekmyrza, Nikita B. Pavzderin, Asset M. Kabyshev, Marzhan M. Kubenova, Gaukhar D. Kabdrakhimova, and Nursultan Aidarbekov. 2022. "Classification of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells" Nanomaterials 12, no. 7: 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12071059

APA StyleKuterbekov, K. A., Nikonov, A. V., Bekmyrza, K. Z., Pavzderin, N. B., Kabyshev, A. M., Kubenova, M. M., Kabdrakhimova, G. D., & Aidarbekov, N. (2022). Classification of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Nanomaterials, 12(7), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12071059