Recent Progress in Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Food Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Types of Contamination

2.1. Chemical Contaminations

2.2. Biological Contaminations

3. Nanotechnology

4. Nanotechnology in Food Monitoring

4.1. Detection of Chemical Contaminations

4.1.1. Nanotechnology Incorporated in Colorimetric Analysis

4.1.2. SERS Analysis

Principles of SERS

Heavy Metals Detection

Detection of Food Allergens

Detection of Antibiotics

Detection of Pesticides

4.1.3. Electrochemical Analysis

Principles of Electrochemical Analysis

Nanomaterials as Electrode Modifiers for Food Analysis

Signal Tags

4.2. Detection of Biological Contaminations

4.2.1. Nanotechnology Incorporated in Immunological Assays

4.2.2. Nanotechnology Incorporated in Molecular Assays

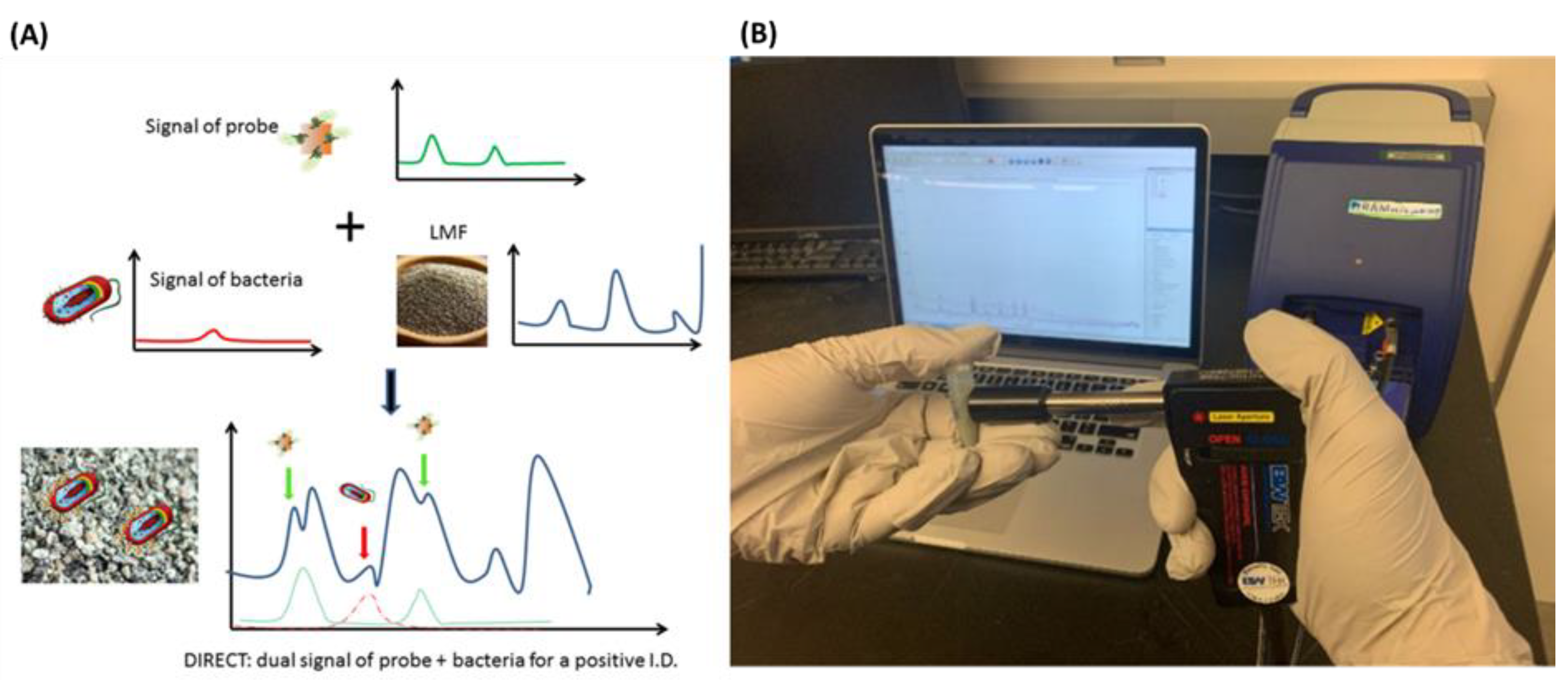

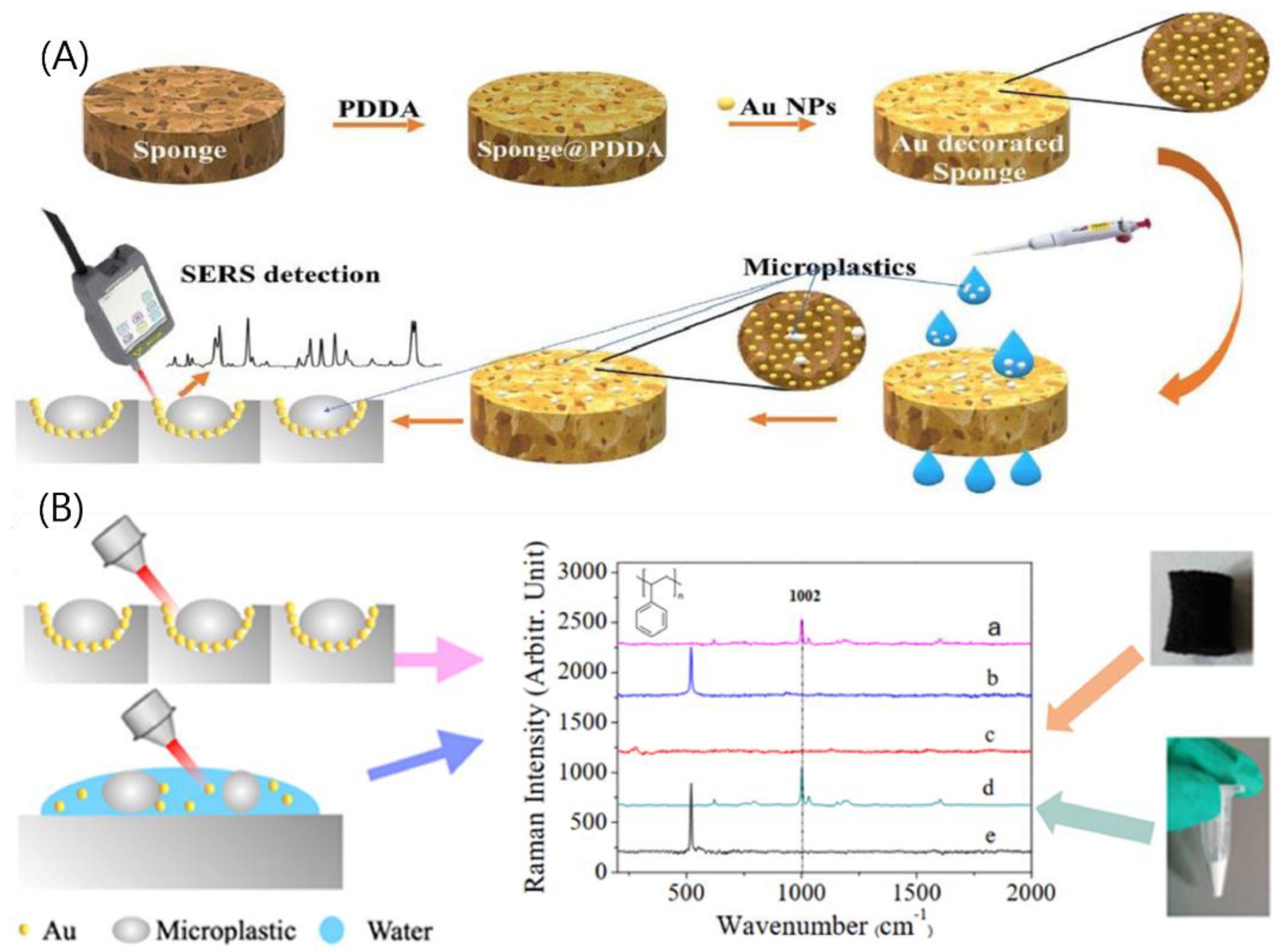

4.3. Detection of Micro/Nanoplastics (MP/NPs)

5. Other Nanomaterial-Based Methodology

5.1. Surface Plasmon Resonance

5.2. Nanoenzymes and Nanopore Sensing

5.3. Reticular Materials-Based Sensor

5.4. Photothermal Assays

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gest, H. The Discovery of Microorganisms by Robert Hooke and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, Fellows of The Royal Society. Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 2004, 58, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz Helene, L.C.; Klepa, M.S.; Hungria, M. New Insights into the Taxonomy of Bacteria in the Genomic Era and a Case Study with Rhizobia. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 4623713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayda, S.; Adeel, M.; Tuccinardi, T.; Cordani, M.; Rizzolio, F. The History of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology: From Chemical–Physical Applications to Nanomedicine. Molecules 2019, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguchi, N. On the Basic Concept of Nanotechnology. Proc. Int. Conf. Prod. Eng. 1974, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Catania, F.; Marras, E.; Giorcelli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Lavagna, L.; Tagliaferro, A.; Bartoli, M. A Review on Recent Advancements of Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials in Biological Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Linke, D. Nanoparticle Classification, Physicochemical Properties, Characterization, and Applications: A Comprehensive Review for Biologists. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.H.; Heo, J.H.; Jung, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Suh, S.-J.; Han, K.H.; Lee, J.H. Portable Au Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Sensor Strip for Rapid On-Site Detection of Cd2+ Ions in Potable Water. BioChip J. 2021, 15, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, G.; Hwang, A.; Kim, H.; Moon, J.; Kang, H.; Jung, J.; Lim, E.-K.; Jeong, J.; Park, H.G.; Kang, T. Ultrasensitive Detection of Ovarian Cancer Biomarker Using Au Nanoplate SERS Immunoassay. BioChip J. 2021, 15, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, P.N.; Sangeetha, K.; Vijayalakshmi, K.; Barhoum, A. Nanomaterials History, Classification, Unique Properties, Production and Market. In Emerging Applications of Nanoparticles and Architecture Nanostructures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 341–384. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, X. Microplastics Are Everywhere—But Are They Harmful? Nature 2021, 593, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanan, K.; Tijare, S.N. Applications of Nanomaterials. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 1093–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.H.; Kim, M. Il Using Nanomaterials in Colorimetric Toxin Detection. BioChip J. 2021, 15, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, S.; Sousa, J.; Pais, A.; Vitorino, C. Nanomedicine: Principles, Properties, and Regulatory Issues. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, F.; Chrostowski, R. Frontiers of Medical Micro/Nanorobotics: In Vivo Applications and Commercialization Perspectives Toward Clinical Uses. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathakoti, K.; Manubolu, M.; Hwang, H.-M. Nanotechnology Applications for Environmental Industry. In Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 894–907. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, F.; Edith; Selly; Adityawarman, D.; Indarto, A. Application of Nanotechnologies in the Energy Sector: A Brief and Short Review. Front. Energy 2013, 7, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Anjum, S.; Hano, C.; Anjum, I.; Abbasi, B.H. An Overview of the Applications of Nanomaterials and Nanodevices in the Food Industry. Foods 2020, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, D.; Kaur, G.; Singh, P.; Yadav, K.; Ali, S.A. Nanoparticle-Based Sustainable Agriculture and Food Science: Recent Advances and Future Outlook. Front. Nanotechnol. 2020, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, Q.; Castle, L. Food Applications of Nanotechnologies: An Overview of Opportunities and Challenges for Developing Countries. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, É. Nanotechnology in Food Systems: A Review. Acta Aliment. 2020, 49, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.L.; Jatav, H.S.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Ranjan, A.; Harikrishnan, A.; Veena, V.K.; Chauhan, A.; Kumar, S.; Prakash, A.; et al. Nanomaterials Based Monitoring of Food- and Water-Borne Pathogens. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 9543532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Andreescu, S. Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Food Sensing and Packaging Applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19309–19336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neethirajan, S.; Jayas, D.S. Nanotechnology for the Food and Bioprocessing Industries. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Baskar, V.; Selvaraj, D.; Nile, A.; Xiao, J.; Kai, G. Nanotechnologies in Food Science: Applications, Recent Trends, and Future Perspectives. Nano Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Raj, G.V.S.B.; Dash, K.K. A Comprehensive Review on Nanotechnology Based Sensors for Monitoring Quality and Shelf Life of Food Products. Meas. Food 2022, 7, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; M.M.S., C.-P.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Shabnam, A.A.; Subrahmanyam, G.; Mondal, R.; Gupta, D.K.; Malyan, S.K.; Kumar, S.S.; et al. Lead Toxicity: Health Hazards, Influence on Food Chain, and Sustainable Remediation Approaches. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.-H. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.A.; Darwish, W.S. Environmental Chemical Contaminants in Food: Review of a Global Problem. J. Toxicol. 2019, 2019, 2345283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonnie, J.M.; Rovina, K.; Mariah, A.M.A.; Erna, K.H.; Felicia, W.X.L.; Aqilah, M.N.N. Trends in Nanotechnology Techniques for Detecting Heavy Metals in Food and Contaminated Water: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, I.A.; Koh, W.Y.; Paek, W.K.; Lim, J. The Sources of Chemical Contaminants in Food and Their Health Implications. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muncke, J.; Andersson, A.-M.; Backhaus, T.; Boucher, J.M.; Carney Almroth, B.; Castillo Castillo, A.; Chevrier, J.; Demeneix, B.A.; Emmanuel, J.A.; Fini, J.-B.; et al. Impacts of Food Contact Chemicals on Human Health: A Consensus Statement. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, A.O.; Garcia, M.V.; Copetti, M.V. Food Industry Spoilage Fungi Control through Facility Sanitization. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 29, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerín, C.; Aznar, M.; Carrizo, D. Food Contamination during Food Process. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 48, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Saavedra, P.; Mendez-Vilabrille, V.; Miranda, J.M.; Nebot, C.; Cardelle-Cobas, A.; Franco, C.M.; Cepeda, A. Food Additives, Contaminants and Other Minor Components: Effects on Human Gut Microbiota—A Review. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 74, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstoff, A.; Niero, M.; Muncke, J.; Trier, X.; Rosenbaum, R.K.; Hauschild, M.; Fantke, P. Challenges of Including Human Exposure to Chemicals in Food Packaging as a New Exposure Pathway in Life Cycle Impact Assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geueke, B.; Groh, K.; Muncke, J. Food Packaging in the Circular Economy: Overview of Chemical Safety Aspects for Commonly Used Materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, T.M.; de Oliveira, D.N.; Melo, C.F.O.R.; de Oliveira Lima, E.; Catharino, R.R. Migration from Plastic Packaging into Meat. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaus, A.L.; Osborn, R.; Krishan, M. Scientific Advances and Challenges in Safety Evaluation of Food Packaging Materials: Workshop Proceedings. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 98, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebelo, K.; Malebo, N.; Mochane, M.J.; Masinde, M. Chemical Contamination Pathways and the Food Safety Implications along the Various Stages of Food Production: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, O.-W.; Wong, S.-K. Contamination in Food from Packaging Material. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 882, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Słowik, J.; Chilicka, K. Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-González, J.M.; Torres-Mora, M.A.; Keesstra, S.; Brevik, E.C.; Jiménez-Ballesta, R. Heavy Metal Accumulation Related to Population Density in Road Dust Samples Taken from Urban Sites under Different Land Uses. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 553, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onakpa, M.M.; Njan, A.A.; Kalu, O.C. A Review of Heavy Metal Contamination of Food Crops in Nigeria. Ann. Glob. Health 2018, 84, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutic, A.; Novakovic, S.; Lutovac, M.; Biocanin, R.; Ketin, S.; Omerovic, N. The Heavy Metals in Agrosystems and Impact on Health and Quality of Life. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briffa, J.; Sinagra, E.; Blundell, R. Heavy Metal Pollution in the Environment and Their Toxicological Effects on Humans. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setia, R.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Singh, R.; Kumar, V.; Taneja, S.; Kukal, S.S.; Pateriya, B. Phytoavailability and Human Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Soils and Food Crops around Sutlej River, India. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Tareq, A.M.; Emran, T.B.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idris, A.M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; et al. Impact of Heavy Metals on the Environment and Human Health: Novel Therapeutic Insights to Counter the Toxicity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, V.; Golia, E.E.; Liu, Y.-T.; Wang, S.-L.; Shaheen, S.M.; Rinklebe, J. Soil and Maize Contamination by Trace Elements and Associated Health Risk Assessment in the Industrial Area of Volos, Greece. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Dai, W.; Gong, S.; Ma, Z. Analysis of Spatial Variations and Sources of Heavy Metals in Farmland Soils of Beijing Suburbs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsdr, U. Toxicological Profile for Mercury; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Chromium. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Chromium (VI) (CASRN 18540-29-9). IRIS, US EPA ORD NCEA Integrated Risk Information System (Vi). Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris2/chemicallanding.cfm?substance_nmbr=141 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- FDA. Lead in Food, Foodwares, and Dietary Supplements; US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Cadmium (CASRN 7440-43-9). IRIS|US EPA. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/ChemicalLanding/&substance_nmbr=144 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Asomugha, R.N.; Udowelle, N.A.; Offor, S.J.; Njoku, C.J.; Ofoma, I.V.; Chukwuogor, C.C.; Orisakwe, O.E. Heavy Metals Hazards from Nigerian Spices. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2016, 67, 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Armendáriz, C.; Paz, S.; Gutiérrez, Á.J.; Gomes Furtado, V.; González-Weller, D.; Revert, C.; Hardisson, A. Toxic Metals in Cereals in Cape Verde: Risk Assessment Evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdinasab, M.; Mishra, R.K.; Tang, X.; Marty, J.L. Detection of Antibiotics in Food: New Achievements in the Development of Biosensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 127, 115883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Lee, K.; Her, J.; Jeon, J.; Mok, J.; So, J.; Shin, S.; Ban, C. Aptasensor for Multiplex Detection of Antibiotics Based on FRET Strategy Combined with Aptamer/Graphene Oxide Complex. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramatla, T.; Ngoma, L.; Adetunji, M.; Mwanza, M. Evaluation of Antibiotic Residues in Raw Meat Using Different Analytical Methods. Antibiotics 2017, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H.S.; Shetty, S.S.; Thomas, N.J.; Dhamu, V.N.; Bhide, A.; Prasad, S. Ultrasensitive and Rapid-Response Sensor for the Electrochemical Detection of Antibiotic Residues within Meat Samples. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 6324–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiber, F.M.; Beranek-Knauer, H. Antimicrobial Residues in Food from Animal Origin—A Review of the Literature Focusing on Products Collected in Stores and Markets Worldwide. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okocha, R.C.; Olatoye, I.O.; Adedeji, O.B. Food Safety Impacts of Antimicrobial Use and Their Residues in Aquaculture. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacanlı, M.; Başaran, N. Importance of Antibiotic Residues in Animal Food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsène, M.M.J.; Davares, A.K.L.; Viktorovna, P.I.; Andreevna, S.L.; Sarra, S.; Khelifi, I.; Sergueïevna, D.M. The Public Health Issue of Antibiotic Residues in Food and Feed: Causes, Consequences, and Potential Solutions. Vet. World 2022, 15, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramić, D.; Klančnik, A.; Možina, S.S.; Dogsa, I. Elucidation of the AI-2 Communication System in the Food-Borne Pathogen Campylobacter jejuni by Whole-Cell-Based Biosensor Quantification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 212, 114439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mshelia, A.B.; Osman, M.; Binti Misni, N. A Cross-Sectional Study Design to Determine the Prevalence of Knowledge, Attitude, and the Preventive Practice of Food Poisoning and Its Factors among Postgraduate Students in a Public University in Selangor, Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.K.; Cross, P.; Burton, M.; Millman, C.; O’Brien, S.J.; Rigby, D. Estimating the Prevalence of Food Risk Increasing Behaviours in UK Kitchens. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, R.; Nguyen-Viet, H.; Tum, S.; Unger, F.; Lindahl, J.; Grace, D.; Ty, C.; Koam, S.; Sina, V.; Sokchea, H.; et al. Experimental Cross-Contamination of Chicken Salad with Salmonella enterica Serovars Typhimurium and London during Food Preparation in Cambodian Households. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegbeleye, O.O.; Singleton, I.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Sources and Contamination Routes of Microbial Pathogens to Fresh Produce during Field Cultivation: A Review. Food Microbiol. 2018, 73, 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.-S.; Menon, S. Food Safety in the 21st Century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaouris, E.; Heir, E.; Desvaux, M.; Hébraud, M.; Møretrø, T.; Langsrud, S.; Doulgeraki, A.; Nychas, G.-J.; Kačániová, M.; Czaczyk, K.; et al. Intra- and Inter-Species Interactions within Biofilms of Important Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galié, S.; García-Gutiérrez, C.; Miguélez, E.M.; Villar, C.J.; Lombó, F. Biofilms in the Food Industry: Health Aspects and Control Methods. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funari, R.; Shen, A.Q. Detection and Characterization of Bacterial Biofilms and Biofilm-Based Sensors. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An Emergent Form of Bacterial Life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, L.M.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A. New Weapons to Fight Old Enemies: Novel Strategies for the (Bio)Control of Bacterial Biofilms in the Food Industry. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, L.; Zhao, L.; Guo, C.; Liu, X.; Qin, L.; Hao, Z. High Prevalence and Diversity Characteristics of BlaNDM, Mcr, and BlaESBLs Harboring Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli From Chicken, Pig, and Cattle in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. 2013. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Ventola, C.L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: Part 1: Causes and threats. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 404, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M.; Guix, S. Foodborne Viruses. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 8, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nainan, O.V.; Xia, G.; Vaughan, G.; Margolis, H.S. Diagnosis of Hepatitis A Virus Infection: A Molecular Approach. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, K.E. Nanosystems: Molecular Machinery, Manufacturing, and Computation; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 1992; ISBN 978-0-471-57518-4. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, A.; Hubler, A.; Bezryadin, A. Self-Assembled Wiggling Nano-Structures and the Principle of Maximum Entropy Production. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, A.J.; Oliver, W.D.; Vandersypen, L.M.K.; Ardavan, A.; Sessoli, R.; Loss, D.; Jayich, A.B.; Fernandez-Rossier, J.; Laucht, A.; Morello, A. Quantum-Coherent Nanoscience. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: A Review of Synthesis Methods, Properties, Recent Progress, and Challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldewachi, H.; Chalati, T.; Woodroofe, M.N.; Bricklebank, N.; Sharrack, B.; Gardiner, P. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Colorimetric Biosensors. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.; Li, D.; Sun, C. Two-Dimensional Boron Sheets as Metal-Free Catalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 19051–19055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduner, E. Size Matters: Why Nanomaterials Are Different. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, N.; Ohnishi, S. Atomic and Electronic Structures of Pd13 and Pt13 Clusters. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58, 1665–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Guo, Y.; Ma, B.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Shuai, M. Fabrication of Highly Dispersed Pd Nanoparticles Supported on Reduced Graphene Oxide for Solid Phase Catalytic Hydrogenation of 1,4-Bis(Phenylethynyl) Benzene. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8385–8395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Ojha, H.; Bharadwaj, A.; Pathak, D.P.; Sharma, R.K. Preparation and Catalytic Applications of Nanomaterials: A Review. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 53381–53403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.W.; Pei, W.; Ma, X.; Xu, X.; Ren, Y.; Sun, W.; Zuo, L. Enhanced Catalytic Activity of Pt Nanomaterials: From Monodisperse Nanoparticles to Self-Organized Nanoparticle-Linked Nanowires. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 6909–6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astruc, D. Introduction: Nanoparticles in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 461–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Shao, S.; Gao, W.; Tang, D.; Tang, D.; Zou, S.; Kim, M.J.; Xia, X. Morphology-Invariant Metallic Nanoparticles with Tunable Plasmonic Properties. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 2428–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Xie, G.; Luo, J. Mechanical Properties of Nanoparticles: Basics and Applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Xu, X.-H.N. Synthesis and Characterization of Tunable Rainbow Colored Colloidal Silver Nanoparticles Using Single-Nanoparticle Plasmonic Microscopy and Spectroscopy. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 9867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y. Accelerated Color Change of Gold Nanoparticles Assembled by DNAzymes for Simple and Fast Colorimetric Pb2+ Detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 12298–12305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Q.; Shao, L.; Shu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, H. Growth of Monodisperse Gold Nanospheres with Diameters from 20 Nm to 220 Nm and Their Core/Satellite Nanostructures. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2014, 2, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jasinski, J.B.; Howell, J.L.; Patel, D.; Stephens, D.P.; Gobin, A.M. Tunability and Stability of Gold Nanoparticles Obtained from Chloroauric Acid and Sodium Thiosulfate Reaction. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Penev, E.S.; Yakobson, B.I. Two-Dimensional Boron: Structures, Properties and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6746–6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyder, A.; Buledi, J.A.; Nawaz, M.; Rajpar, D.B.; Shah, Z.-H.; Orooji, Y.; Yola, M.L.; Karimi-Maleh, H.; Lin, H.; Solangi, A.R. Identification of Heavy Metal Ions from Aqueous Environment through Gold, Silver and Copper Nanoparticles: An Excellent Colorimetric Approach. Environ. Res. 2022, 205, 112475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharmaraj, V.; Yang, J. Sensitive and Selective Colorimetric Detection of Cu2+ in Aqueous Medium via Aggregation of Thiomalic Acid Functionalized Ag Nanoparticles. Analyst 2014, 139, 6304–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Chan, H.T.; Chen, Q.; Chen, H. Application of Nanotechnology in Analysis and Removal of Heavy Metals in Food and Water Resources. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Li, F.; Du, C.; Fu, Y. A Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Nanosensor Based on Rhombic Ag Nanoparticle Array. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 134, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Jain, V.; Nagpal, S. Nanoparticle Intervention for Heavy Metal Detection: A Review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2022, 17, 100667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.L.; Noguez, C.; Beránek, J.; Barnard, A.S. Size, Shape, Stability, and Color of Plasmonic Silver Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 9128–9136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markin, A.V.; Markina, N.E. Experimenting with Plasmonic Copper Nanoparticles To Demonstrate Color Changes and Reactivity at the Nanoscale. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 1438–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, I.; Gangwar, C.; Yaseen, B.; Pandey, P.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Naik, R.M. Kinetic and Mechanistic Studies of the Formation of Silver Nanoparticles by Nicotinamide as a Reducing Agent. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 13778–13788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ma, X.; Gu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, G. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles and Their Potential Applications to Treat Cancer. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Deng, L.; Yonezawa, T. Control of Nanoparticles Synthesized via Vacuum Sputter Deposition onto Liquids: A Review. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDarby, S.P.; Wang, C.J.; King, M.E.; Personick, M.L. An Integrated Electrochemistry Approach to the Design and Synthesis of Polyhedral Noble Metal Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 21322–21335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, L.; Blanco, M.C.; López-Quintela, M.A. Electrochemical Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 9683–9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Matsubara, S.; Xiong, L.; Hayakawa, T.; Nogami, M. Solvothermal Synthesis of Multiple Shapes of Silver Nanoparticles and Their SERS Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 9095–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studart, A.R.; Amstad, E.; Gauckler, L.J. Colloidal Stabilization of Nanoparticles in Concentrated Suspensions. Langmuir 2007, 23, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Ghosh, M.M. Effect of Stabilizer Concentration on the Size of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized through Chemical Route. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 123, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, E.; Pradhan, N. Metal-Induced Aggregation of Valine Capped Gold Nanoparticles: An Efficient and Rapid Approach for Colorimetric Detection of Pb2+ Ions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-H.; Ren, S.; Zhuo, Y.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.-Q. Cu/Mn Double-Doped CeO2 Nanocomposites as Signal Tags and Signal Amplifiers for Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Procalcitonin. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 13349–13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, P.; Wang, C.; Tao, H.; Wu, Y. Colorimetric Detection of Kanamycin Residue in Foods Based on the Aptamer-Enhanced Peroxidase-Mimicking Activity of Layered WS2 Nanosheets. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2884–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, B.; Bao, Q.; Yang, T.; Wei, T.; Wang, J.; Mao, C.; Zhang, C.; Yang, M. Aptamer-Modified Sensitive Nanobiosensors for the Specific Detection of Antibiotics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8607–8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, F.; Li, F.; Kong, Q.; Guo, Y.; Sun, X. Recent Advances in Aptamer-Based Sensors for Aminoglycoside Antibiotics Detection and Their Applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 143129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Tan, W.; Zu, Y. Aptamers: Versatile Molecular Recognition Probes for Cancer Detection. Analyst 2016, 141, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J.; Xiang, Y. Colorimetric Aptasensors for Determination of Tobramycin in Milk and Chicken Eggs Based on DNA and Gold Nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2018, 249, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, P.; Chen, R.; Xiao, R.; Pang, Y. Split Aptamer Regulated CRISPR/Cas12a Biosensor for 17β-Estradiol through a Gap-Enhanced Raman Tags Based Lateral FLow Strategy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 215, 114548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, Y.; Jialading, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Application of SERS Quantitative Analysis Method in Food Safety Detection. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 40, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Xu, M.; Ren, B.; Tian, Z. Development of Weak Signal Recognition and an Extraction Algorithm for Raman Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 12909–12916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.R.; Hooper, D.C.; Zhang, L.; Wolverson, D.; Valev, V.K. Raman Techniques: Fundamentals and Frontiers. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewumi, B.; Feldman, M.; Biswas, D.; Cao, D.; Jiang, L.; Korivi, N. Low-Cost Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering for Bio-Probes. Solids 2022, 3, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Lu, G. Recent Developments of Flexible and Transparent SERS Substrates. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 3956–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, E.; Shi, H.; Tao, Y.; Ren, X. Semiconductor-Based Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS): From Active Materials to Performance Improvement. Analyst 2022, 147, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Gong, H.; Jiang, L.; Sun, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Dual-Functional Ultrathin Wearable 3D Particle-in-Cavity SF-AAO-Au SERS Sensors for Effective Sweat Glucose and Lab-on-Glove Pesticide Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 359, 131512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, C.; Yan, Y.; Xiong, W.; Ren, J.; Luo, W. MoS2-Based Substrates for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering: Fundamentals, Progress and Perspective. Coatings 2022, 12, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, N.N.; Bui, T.L.; Son, S.J.; Joo, S. Ultrasonication-Induced Self-Assembled Fixed Nanogap Arrays of Monomeric Plasmonic Nanoparticles inside Nanopores. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1809146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshkeiti, A.; Narakathu, B.B.; Reddy, A.S.G.; Moorthi, A.; Atashbar, M.Z.; Rebrosova, E.; Rebros, M.; Joyce, M. Detection of Heavy Metal Compounds Using a Novel Inkjet Printed Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Substrate. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 171–172, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barimah, A.O.; Guo, Z.; Agyekum, A.A.; Guo, C.; Chen, P.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Zou, X.; Chen, Q. Sensitive Label-Free Cu2O/Ag Fused Chemometrics SERS Sensor for Rapid Detection of Total Arsenic in Tea. Food Control 2021, 130, 108341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chałabis-Mazurek, A.; Rechulicz, J.; Pyz-Łukasik, R. A Food-Safety Risk Assessment of Mercury, Lead and Cadmium in Fish Recreationally Caught from Three Lakes in Poland. Animals 2021, 11, 3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H. Advances in Methylmercury Toxicology and Risk Assessment. Toxics 2019, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Tokumoto, M.; Hwang, G.-W.; Kim, M.-S.; Takahashi, T.; Naganuma, A.; Yoshida, M.; Satoh, M. Effect of Metallothionein-III on Mercury-Induced Chemokine Gene Expression. Toxics 2018, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Dong, C.; Wang, L. Colorimetric/SERS Dual-Mode Detection of Mercury Ion via SERS-Active Peroxidase-like Au@AgPt NPs. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 310, 127849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Han, Y.; Huang, Y.; Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y. Reusable Dual-Enhancement SERS Sensor Based on Graphene and Hybrid Nanostructures for Ultrasensitive Lead (II) Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 341, 130031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, T.; Wu, Z.; Yu, R. Novel Ratiometric Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Aptasensor for Sensitive and Reproducible Sensing of Hg2+. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 99, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qi, Q.; Wang, C.; Qian, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensors for Food Allergen Detection in Food Matrices. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 142, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.-L.; Gao, Y.; Han, X.-X.; Zhao, B. Innovative Application of SERS in Food Quality and Safety: A Brief Review of Recent Trends. Foods 2022, 11, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Weng, X.; Tah, A.; Cordero, J.O.; Ragavan, K.V. Nano-Biosensor Platforms for Detecting Food Allergens—New Trends. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2018, 18, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriz, E.; García-Fernández, M.C.; Lechuga, L.M. Towards the Design of Universal Immunosurfaces for SPR-Based Assays: A Review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 79, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Liang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Mao, H.; Sun, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Hu, W.; Xu, G.; et al. Effect of the Duty Cycle of Flower-like Silver Nanostructures Fabricated with a Lyotropic Liquid Crystal on the SERS Spectrum. Molecules 2021, 26, 6522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Yu, Q. The Development of Lateral Flow Immunoassay Strip Tests Based on Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Coupled with Gold Nanoparticles for the Rapid Detection of Soybean Allergen β-Conglycinin. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 241, 118640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, N.; Yao, T.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Relying on Bimetallic Au–Ag Nanourchins for the Detection of the Food Allergen β-Lactoglobulin. Talanta 2022, 245, 123445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lee, D.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, K.; Joo, J.; Kim, W.B.; Song, Y.B.; Jung, Y.S.; Park, J. Synthesis of Nano-Sized Urchin-Shaped LiFePO4 for Lithium Ion Batteries. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13714–13721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, C.; Navas, D.; Lavayen, V.; Benavente, E.; Santa Ana, M.A.; González, G.; Newcomb, S.B.; Sotomayor Torres, C.M. Nano-Urchin: The Formation and Structure of High-Density Spherical Clusters of Vanadium Oxide Nanotubes. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 3016–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Li, Y.; Miao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, J.; Yu, T.; Liu, J. Sensitive Detection of Antibiotics Using Aptamer Conformation Cooperated Enzyme-Assisted SERS Technology. Analyst 2019, 144, 3649–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Mao, Z.; Shi, X. Silver Nanoparticle-Decorated TiO2 Nanotube Array for Solid-Phase Microextraction and SERS Detection of Antibiotic Residue in Milk. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 255, 119652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Chen, S.; Ma, X.; Shao, H.; Zhan, J. Galvanic Displacement-Induced Codeposition of Reduced-Graphene-Oxide/Silver on Alloy Fibers for Non-Destructive SPME@SERS Analysis of Antibiotics. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Zhai, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Rasco, B.A.; Huang, Y. Application of Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Analyses of Restricted Sulfa Drugs. Sens. Instrum. Food Qual. Saf. 2011, 5, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markina, N.E.; Markin, A.V.; Weber, K.; Popp, J.; Cialla-May, D. Liquid-Liquid Extraction-Assisted SERS-Based Determination of Sulfamethoxazole in Spiked Human Urine. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1109, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L.; Jiao, A.; Chen, F.; Chen, M. Construction of Optimized Au@Ag Core-Shell Nanorods for Ultralow SERS Detection of Antibiotic Levofloxacin Molecules. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 23347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lin, M.; Li, H.; Kim, N.-J. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Coupled with Dendritic Silver Nanosubstrate for Detection of Restricted Antibiotics. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009, 41, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamián-López, M.B.; Poppi, R.J. Quantification of Moxifloxacin in Urine Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Multivariate Curve Resolution on a Nanostructured Gold Surface. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 7671–7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Qin, X.; Yin, D.; Gong, M.; Yang, L.; Zhao, B.; Ruan, W. Rapid Monitoring of Benzylpenicillin Sodium Using Raman and Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 140, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Yang, M.; Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Yang, L.; Zhao, B. SERS Investigation and High Sensitive Detection of Carbenicillin Disodium Drug on the Ag Substrate. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 204, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Sang, Q.; Yang, M.; Du, J.; Yang, L.; Jiang, X.; Han, X.; Zhao, B. Detection of Several Quinolone Antibiotic Residues in Water Based on Ag-TiO2 SERS Strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Geng, Z.-Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Han, C.-Q.; Yang, G.-H.; Li, H.; Qu, L.-L. Highly Reproducible Solid-Phase Extraction Membrane for Removal and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Detection of Antibiotics. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 14989–14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syafrudin, M.; Kristanti, R.A.; Yuniarto, A.; Hadibarata, T.; Rhee, J.; Al-onazi, W.A.; Algarni, T.S.; Almarri, A.H.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M. Pesticides in Drinking Water—A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, Z.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Ling, C.; Yuan, Y.; Meng, Q.; Cui, X.; Park, A.S.; Uldall, P.; Olsen, J.; Cockburn, M.; et al. Ambient Exposure to Agricultural Pesticides during Pregnancy and Risk of Cerebral Palsy: A Population-Based Study in California. Toxics 2020, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feulefack, J.; Khan, A.; Forastiere, F.; Sergi, C.M. Parental Pesticide Exposure and Childhood Brain Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Confirming the IARC/WHO Monographs on Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides. Children 2021, 8, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, R.; Iacob, B.-C.; Farcău, C.; Bodoki, E.; Oprean, R. Strategies for SERS Detection of Organochlorine Pesticides. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, N.N.; Bui, T.L.; Ho, N.T.; Son, S.J.; Joo, S.-W. Controlling Photocatalytic Reactions and Hot Electron Transfer by Rationally Designing Pore Sizes and Encapsulated Plasmonic Nanoparticle Numbers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 23497–23504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Yang, T.; He, L. Review of Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic (SERS) Detection of Synthetic Chemical Pesticides. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 85, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-Y.; Lin, P.-Y.; Li, J.-S.; Kirankumar, R.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Chen, N.-F.; Wen, Z.-H.; Hsieh, S. A Novel SERS Substrate Based on Discarded Oyster Shells for Rapid Detection of Organophosphorus Pesticide. Coatings 2022, 12, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Lin, L.; He, Y.; Nie, P.; Qu, F.; Xiao, S. Density Functional Theory Analysis of Deltamethrin and Its Determination in Strawberry by Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Molecules 2018, 23, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Mehedi Hassan, M.; Zhu, J.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, W.; Wang, J.; Lv, C.; Chen, Q.; Li, H. Quantification of Deltamethrin Residues in Wheat by Ag@ZnO NFs-Based Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Coupling Chemometric Models. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Nie, P.; Xia, Z.; Feng, X.; Liu, X.; He, Y. Rapid Quantitative Detection of Deltamethrin in Corydalis Yanhusuo by SERS Coupled with Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Molecules 2020, 25, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutta, S.; Prasad, J.; Gunasekaran, K.; Iyadurai, R. Hepatotoxicity and Neurotoxicity of Fipronil Poisoning in Human: A Case Report. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nghi, N.Đ.; Kim, Y.-H.; Joo, S.-W. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Detection of Fipronil Pesticide Adsorbed on Silver Nanoparticles. Sensors 2019, 19, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, M.; Yao, G.; Zhong, J.; Chao, K.; Aziz, M.H.; Huang, Q. A Facile and Label-Free SERS Approach for Inspection of Fipronil in Chicken Eggs Using SiO2@Au Core/Shell Nanoparticles. Talanta 2020, 207, 120324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, N.; Haughey, S.A.; Liu, L.; Burns, D.T.; Quinn, B.; Cao, C.; Elliott, C.T. Handheld SERS Coupled with QuEChERs for the Sensitive Analysis of Multiple Pesticides in Basmati Rice. NPJ Sci. Food 2022, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikac, L.; Kovacevic, E.; Ukic, S.; Raic, M.; Jurkin, T.; Maric, I.; Gotic, M.; Ivanda, M. Detection of Multi-Class Pesticide Residues with Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 252, 119478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Huang, Q. Flexible and Transparent SERS Substrates Composed of Au@Ag Nanorod Arrays for In Situ Detection of Pesticide Residues on Fruit and Vegetables. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, A.B.; Czaplicka, M.; Kowalska, A.A.; Szymborski, T.; Kamińska, A. Flexible PET/ITO/Ag SERS Platform for Label-Free Detection of Pesticides. Biosensors 2019, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, D.; Sun, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Yi, L.; Wang, S. Recent Advances in Nanomaterial-assisted Electrochemical Sensors for Food Safety Analysis. Food Front. 2022, 3, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povedano, E.; Vargas, E.; Montiel, V.R.-V.; Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Pedrero, M.; Barderas, R.; Segundo-Acosta, P.S.; Peláez-García, A.; Mendiola, M.; Hardisson, D.; et al. Electrochemical Affinity Biosensors for Fast Detection of Gene-Specific Methylations with No Need for Bisulfite and Amplification Treatments. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahdost-fard, F.; Roushani, M. Impedimetric Detection of Trinitrotoluene by Using a Glassy Carbon Electrode Modified with a Gold Nanoparticle@fullerene Composite and an Aptamer-Imprinted Polydopamine. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 3997–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, S.; Dourandish, Z.; Garkani Nejad, F.; Beitollahi, H.; Jahani, P.M.; Di Bartolomeo, A. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides: Synthesis and Use in the Development of Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 216, 114674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Durairaj, S.; Prins, S.; Chen, A. Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors for the Detection of Pharmaceutical Compounds. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 175, 112836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, I.; Unwin, P.R.; Macpherson, J.V. Electrochemistry at Carbon Nanotubes: Perspective and Issues. Chem. Commun. 2009, 45, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Chirtes, S.; Liu, X.; Eriksson, M.; Mak, W.C. A Green Route for Lignin-Derived Graphene Electrodes: A Disposable Platform for Electrochemical Biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 218, 114742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.A.; Kwon, N.; Park, E.; Kim, Y.; Jang, H.; Min, J.; Lee, T. Electrochemical Biosensor with Aptamer/Porous Platinum Nanoparticle on Round-Type Micro-Gap Electrode for Saxitoxin Detection in Fresh Water. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 210, 114300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.S.; Shereema, R.M.; Ramachandran, V.; Sruthi, T.V.; Kumar, V.B.S.; Rakhi, R.B. Carbon Quantum Dot-Modified Carbon Paste Electrode-Based Sensor for Selective and Sensitive Determination of Adrenaline. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 7903–7910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrabelj, T.; Finšgar, M. Recent Progress in Non-Enzymatic Electroanalytical Detection of Pesticides Based on the Use of Functional Nanomaterials as Electrode Modifiers. Biosensors 2022, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zuo, X.; Su, S.; Tang, Z.; Wu, A.; Song, S.; Zhang, D.; Fan, C. An Electrochemical Sensor for Pesticide Assays Based on Carbon Nanotube-Enhanced Acetycholinesterase Activity. Analyst 2008, 133, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, A.; Ramasamy Raja, V.; Karuppasamy, P.; Suganthi, A.; Rajarajan, M. Electrochemical Behaviour and Voltammetric Determination of Mercury (II) Ion in Cupric Oxide/Poly Vinyl Alcohol Nanocomposite Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Microchem. J. 2019, 145, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.J.; Vázquez, M.D.; Debán, L.; Aller, A.J. Inorganic Arsenic Speciation by Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry Using Thoria Nanoparticles-Carbon Paste Electrodes. Talanta 2016, 152, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisoc, S.; Vitto, R.I.M.; Natividad, M. Determination of Heavy Metals in Herbal Food Supplements Using Bismuth/Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes/Nafion Modified Graphite Electrodes Sourced from Waste Batteries. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Rahm, C.E.; Griesmer, B.; Alvarez, N.T. Carbon Nanotube Microelectrode Set: Detection of Biomolecules to Heavy Metals. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 7439–7448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayen, P.; Chaplin, B.P. Selective Electrochemical Detection of Ciprofloxacin with a Porous Nafion/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Composite Film Electrode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 1615–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, A.; Tahir, M.A.; Shaheen, A.; Lieberzeit, P.A.; Khan, W.S.; Bajwa, S.Z. Investigating Nanohybrid Material Based on 3D CNTs@Cu Nanoparticle Composite and Imprinted Polymer for Highly Selective Detection of Chloramphenicol. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 342, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebelo, P.; Pacheco, J.G.; Voroshylova, I.V.; Melo, A.; Cordeiro, M.N.D.S.; Delerue-Matos, C. Rational Development of Molecular Imprinted Carbon Paste Electrode for Furazolidone Detection: Theoretical and Experimental Approach. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 329, 129112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H.; Marquette, C.A.; Dutta, P.; Rajesh; Sumana, G. Integrated Graphene Quantum Dot Decorated Functionalized Nanosheet Biosensor for Mycotoxin Detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 7029–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z. Quantum Dots@porous Carbon Platform for the Electrochemical Sensing of Oxytetracycline. Microchem. J. 2021, 167, 106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekry, A.M.; Shehata, M.; Azab, S.M.; Walcarius, A. Voltammetric Detection of Caffeine in Pharmacological and Beverages Samples Based on Simple Nano-Co (II, III) Oxide Modified Carbon Paste Electrode in Aqueous and Micellar Media. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 302, 127172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.M. Nitrate. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 523–527. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, W.J.R.; Lima, P.R.; Tanaka, A.A.; Tanaka, S.M.C.N.; Kubota, L.T. Determination of Nitrite in Food Samples by Anodic Voltammetry Using a Modified Electrode. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 1206–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim-Nezhad, G.; Khorablou, Z.; Zamani, M.; Seyed Dorraji, P.; Alamgholiloo, M. Voltammetric Sensor for Tartrazine Determination in Soft Drinks Using Poly (p-Aminobenzenesulfonic Acid)/Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Carbon Paste Electrode. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017, 25, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Cui, X.; Li, H.; Lu, J.; Kang, Q.; Shen, D. A Ratiometric Electrochemical Sensor for Multiplex Detection of Cancer Biomarkers Using Bismuth as an Internal Reference and Metal Sulfide Nanoparticles as Signal Tags. Analyst 2019, 144, 4073–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Dong, T.; Wang, Z.; Bao, J.; Tu, W.; Dai, Z. Aggregation of Individual Sensing Units for Signal Accumulation: Conversion of Liquid-Phase Colorimetric Assay into Enhanced Surface-Tethered Electrochemical Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8880–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen Inbaraj, B.; Chen, B.H. Nanomaterial-Based Sensors for Detection of Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens and Toxins as Well as Pork Adulteration in Meat Products. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.F.D.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Magalhães, J.M.C.S.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Freire, C.; Delerue-Matos, C. Development of a Disposable Paper-Based Potentiometric Immunosensor for Real-Time Detection of a Foodborne Pathogen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Guo, R.; Huang, F.; Qi, W.; Liu, Y.; Cai, G.; Lin, J. An Impedance Biosensor Based on Magnetic Nanobead Net and MnO2 Nanoflowers for Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Foodborne Bacteria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 173, 112800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Li, H.; Jiang, X. Detection of Foodborne Pathogens Using Bioconjugated Nanomaterials. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2008, 5, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.W.-F.; Ab Mutalib, N.-S.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H. Rapid Methods for the Detection of Foodborne Bacterial Pathogens: Principles, Applications, Advantages and Limitations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hariri, A.A.; Newman, S.S.; Tan, S.; Mamerow, D.; Adams, A.M.; Maganzini, N.; Zhong, B.L.; Eisenstein, M.; Dunn, A.R.; Soh, H.T. Improved Immunoassay Sensitivity and Specificity Using Single-Molecule Colocalization. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Gupta, N.K.; Huang, H.-J.; Lam, C.H.; Huang, C.-L.; Tan, K.-T. Affinity-Switchable Lateral Flow Assay. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 5556–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Pingguan-Murphy, B.; Lu, T.J.; Xu, F. Advances in Paper-Based Point-of-Care Diagnostics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 54, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, J.H.; Chan, H.-M.; Ying, J.Y. Strategies for Developing Sensitive and Specific Nanoparticle-Based Lateral Flow Assays as Point-of-Care Diagnostic Device. Nano Today 2020, 30, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.Y.; Shah, K. Nanobodies: Next Generation of Cancer Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napione, L. Integrated Nanomaterials and Nanotechnologies in Lateral Flow Tests for Personalized Medicine Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Bai, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Nanobody-Based Immunochromatographic Biosensor for Colorimetric and Photothermal Dual-Mode Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 369, 132371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ren, Y.; Guo, B.; Yang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Development of a Specific Nanobody and Its Application in Rapid and Selective Determination of Salmonella enteritidis in Milk. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Pang, B.; Song, X.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C. Colorimetric Immunoassay for Rapid Detection of Vibrio parahemolyticus Based on Mn2+ Mediates the Assembly of Gold Nanoparticles. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 9516–9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, H.; Tayyarcan, E.K.; Caglayan, M.G.; Boyaci, İ.H.; Saglam, N.; Tamer, U. Replacement of Antibodies with Bacteriophages in Lateral Flow Assay of Salmonella enteritidis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 189, 113383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Yu, Z.; Liu, D.; Xu, C.; Lai, W. Developing a Novel Immunochromatographic Test Strip with Gold Magnetic Bifunctional Nanobeads (GMBN) for Efficient Detection of Salmonella choleraesuis in Milk. Food Control 2016, 59, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Lorenzo, L.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Bhunia, A.K.; Espiña, B.; Prado, M.; Diéguez, L.; Abalde-Cela, S. Gold Nanostars for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogens via Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Combined with Microfluidics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 6081–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, S.; Condell, O.; McClure, P.; Amézquita, A.; Fanning, S. Mechanisms of Survival, Responses and Sources of Salmonella in Low-Moisture Environments. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Zhu, B.; Yu, C. A Dual Immunological Raman-Enabled Crosschecking Test (DIRECT) for Detection of Bacteria in Low Moisture Food. Biosensors 2020, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, K.T.L.; Trinh, T.N.D.; Lee, N.Y. Fully Integrated and Slidable Paper-Embedded Plastic Microdevice for Point-of-Care Testing of Multiple Foodborne Pathogens. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 135, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.A.; Lee, N.Y. Polydopamine Aggregation: A Novel Strategy for Power-Free Readout of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Integrated into a Paper Device for Multiplex Pathogens Detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 189, 113353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liang, T.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Yue, Z.; Lv, J.; Jiang, Q.; Yi, C. Ultrasensitive Detection and Rapid Identification of Multiple Foodborne Pathogens with the Naked Eyes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 71, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Song, M.; Cui, Y.; Shi, C.; Wang, D.; Paoli, G.C.; Shi, X. A Rapid Method for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogens by Extraction of a Trace Amount of DNA from Raw Milk Based on Amino-Modified Silica-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles and Polymerase Chain Reaction. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 787, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Qu, L.; Wimbrow, A.N.; Jiang, X.; Sun, Y. Rapid Detection of Listeria Monocytogenes by Nanoparticle-Based Immunomagnetic Separation and Real-Time PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 118, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Tian, F.; Kong, Y.; Titushikin, I.; Gao, H. Effects of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Nanotechnology 2004, 15, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, C.; Wang, M.; Han, H.; Cao, X. Aqueous Suspension of Carbon Nanotubes Enhances the Specificity of Long PCR. Biotechniques 2008, 44, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, B.M.; Nam, N.N.; Son, S.J.; Lee, N.Y. Nanoporous Anodic Aluminum Oxide Internalized with Gold Nanoparticles for On-Chip PCR and Direct Detection by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Analyst 2018, 143, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Huang, J.; Lv, J.; An, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, C.; Hu, J. Nanoparticle PCR: Nanogold-Assisted PCR with Enhanced Specificity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5100–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M. Enhancing the Efficiency of a PCR Using Gold Nanoparticles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.; Paris, J.L.; Roumani, F.; Diéguez, L.; Prado, M.; Espiña, B.; Abalde-Cela, S.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Rodriguez-Lorenzo, L. Multifuntional Gold Nanoparticles for the SERS Detection of Pathogens Combined with a LAMP–in–Microdroplets Approach. Materials 2020, 13, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Maestu, A.; Azinheiro, S.; Carvalho, J.; Abalde-Cela, S.; Carbó-Argibay, E.; Diéguez, L.; Piotrowski, M.; Kolen’ko, Y.V.; Prado, M. Combination of Microfluidic Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification with Gold Nanoparticles for Rapid Detection of Salmonella Spp. in Food Samples. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strungaru, S.-A.; Jijie, R.; Nicoara, M.; Plavan, G.; Faggio, C. Micro- (Nano) Plastics in Freshwater Ecosystems: Abundance, Toxicological Impact and Quantification Methodology. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto da Costa, J.; Reis, V.; Paço, A.; Costa, M.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Micro(Nano)Plastics—Analytical Challenges towards Risk Evaluation. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 111, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental Exposure to Microplastics: An Overview on Possible Human Health Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, M.; Châtel, A.; Mouneyrac, C. Micro(Nano)Plastics: A Threat to Human Health? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 1, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruti, V.C.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Elizalde-Martínez, I.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G. Toward a Unified Framework for Investigating Micro(Nano)Plastics in Packaged Beverages Intended for Human Consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, A.; Kannan, D.; Kapoor, A.; Prabhakar, S. Extraction and Detection Methods of Microplastics in Food and Marine Systems: A Critical Review. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rout, P.R.; Mohanty, A.; Aastha; Sharma, A.; Miglani, M.; Liu, D.; Varjani, S. Micro- and Nanoplastics Removal Mechanisms in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 6, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, Y.; Chung, H. Feasibility Study for Simple On-Line Raman Spectroscopic Detection of Microplastic Particles in Water Using Perfluorocarbon as a Particle-Capturing Medium. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1165, 338518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.; He, L.; Jiang, S.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C.; Qu, J.; Lu, Y.; Hong, P.; Sun, S.; Li, C. In Situ Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy for Detecting Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Aquatic Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.; Ge, H.; Chen, H.; Du, J.; Sun, Z.; Tan, H.; Wang, S. Sensitive and Rapid Detection of Trace Microplastics Concentrated through Au-Nanoparticle-Decorated Sponge on the Basis of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Environ. Adv. 2021, 5, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martic, S.; Tabobondung, M.; Gao, S.; Lewis, T. Emerging Electrochemical Tools for Microplastics Remediation and Sensing. Front. Sens. 2022, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, A.; Kirsten, K.L.; Ajmal, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zhao, X. Alternative Plasticizers As Emerging Global Environmental and Health Threat: Another Regrettable Substitution? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurudatt, N.G.; Lee, K.; Heo, W.; Jung, H.-I. A Simple Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Detection of Dbp Plasticizer for the Risk Assessment of the South Korean River Water. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 147, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, K.; Makowska, K.; Całka, J.; Gonkowski, S. The Endocrine Disruptor Bisphenol A (BPA) Affects the Enteric Neurons Immunoreactive to Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) in the Enteric Nervous System of the Porcine Large Intestine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naomi, R.; Yazid, M.D.; Bahari, H.; Keong, Y.Y.; Rajandram, R.; Embong, H.; Teoh, S.H.; Halim, S.; Othman, F. Bisphenol A (BPA) Leading to Obesity and Cardiovascular Complications: A Compilation of Current In Vivo Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Arreola, M.I.; Moreno-Mendoza, N.A.; Nava-Castro, K.E.; Segovia-Mendoza, M.; Perez-Torres, A.; Garay-Canales, C.A.; Morales-Montor, J. The Endocrine Disruptor Compound Bisphenol-A (BPA) Regulates the Intra-Tumoral Immune Microenvironment and Increases Lung Metastasis in an Experimental Model of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.U.; Deen, M.J. Bisphenol A Electrochemical Sensor Using Graphene Oxide and β-Cyclodextrin-Functionalized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 5532–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghayeri, M.; Amiri, A.; Fayazi, M.; Nodehi, M.; Esmaeelnia, A. Electrochemical Detection of Bisphenol a on a MWCNTs/CuFe2O4 Nanocomposite Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 261, 124247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, M.; Hunsicker, E.; Platt, M. A Tunable Three-Dimensional Printed Microfluidic Resistive Pulse Sensor for the Characterization of Algae and Microplastics. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2578–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, C.; Brolo, A.G. Periodic Metallic Nanostructures as Plasmonic Chemical Sensors. Langmuir 2013, 29, 5638–5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, N.; Kumar, S.; Yashini, M.; Rajeshwari, S.; Mamathi, C.A.; Thirunavookarasu, S.N.; Sunil, C.K. Recent Advances in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Biosensors for Food Analysis: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K.L.M.; Lemass, D.; O’Kennedy, R. Surface Plasmon Resonance–Based Immunoassays. In Handbook of Immunoassay Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 129–156. [Google Scholar]

- Pesavento, M.; Zeni, L.; De Maria, L.; Alberti, G.; Cennamo, N. SPR-Optical Fiber-Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Sensor for the Detection of Furfural in Wine. Biosensors 2021, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Ran, Z.; Wang, R.; Ren, Z.; Liu, C.-L.; Liu, C.-B.; Shi, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.-H. Twisted Fiber Optic SPR Sensor for GDF11 Concentration Detection. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiu, M.; Bala, C. SPR and SPR Imaging: Recent Trends in Developing Nanodevices for Detection and Real-Time Monitoring of Biomolecular Events. Sensors 2016, 16, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Zou, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Y. Recent Progress in Spectroscopic Methods for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogenic Bacteria. Biosensors 2022, 12, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemura, K. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)- and Localized SPR (LSPR)-Based Virus Sensing Systems: Optical Vibration of Nano- and Micro-Metallic Materials for the Development of Next-Generation Virus Detection Technology. Biosensors 2021, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, H.; Song, H.; Choi, J.; Kim, K. A Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Using Double-Metal-Complex Nanostructures and a Review of Recent Approaches. Sensors 2017, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, M.G.; Taya, S.A.; Colak, I.; Patel, S.K.; Olaimat, M.M.; Ramahi, O. Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor Based on Graphene Layer for the Detection of Waterborne Bacteria. J. Biophotonics 2022, 15, e202200001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhou, S.; Wang, G.; Yun, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W. Nanozyme Applications: A Glimpse of Insight in Food Safety. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ren, M.; Zhang, P.; Jiang, D.; Yao, X.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y. Application of Nanopore Sequencing in the Detection of Foodborne Microorganisms. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ding, F.; Yin, W.; Ma, J.; Wang, B.; Nie, A.; Han, H. From Electrochemistry to Electroluminescence: Development and Application in a Ratiometric Aptasensor for Aflatoxin B1. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 7578–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wan, K.; Shi, X. Recent Advances in Nanozyme Research. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1805368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S. A CeO2@MnO2 Core–Shell Hollow Heterojunction as Glucose Oxidase-like Photoenzyme for Photoelectrochemical Sensing of Glucose. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 304, 127389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Li, F. Two-Dimensional MnO2 Nanozyme-Mediated Homogeneous Electrochemical Detection of Organophosphate Pesticides without the Interference of H2O2 and Color. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 4084–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhou, M.; Liu, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y. Double-Enzymes-Mediated Fe2+/Fe3+ Conversion as Magnetic Relaxation Switch for Pesticide Residues Sensing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savas, S.; Altintas, Z. Graphene Quantum Dots as Nanozymes for Electrochemical Sensing of Yersinia Enterocolitica in Milk and Human Serum. Materials 2019, 12, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.R.; Siwy, Z.S. Learning Nature’s Way: Biosensing with Synthetic Nanopores. Science 2007, 317, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liefting, L.W.; Waite, D.W.; Thompson, J.R. Application of Oxford Nanopore Technology to Plant Virus Detection. Viruses 2021, 13, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Player, R.; Verratti, K.; Staab, A.; Forsyth, E.; Ernlund, A.; Joshi, M.S.; Dunning, R.; Rozak, D.; Grady, S.; Goodwin, B.; et al. Optimization of Oxford Nanopore Technology Sequencing Workflow for Detection of Amplicons in Real Time Using ONT-DART Tool. Genes 2022, 13, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Hui, J.; Mao, H. Nanopore Technology and Its Applications in Gene Sequencing. Biosensors 2021, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forghani, F.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Mann, D.A.; Deng, X.; den Bakker, H.C.; Diez-Gonzalez, F. Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli in Wheat Flour: Detection and Serotyping by a Quasimetagenomic Approach Assisted by Magnetic Capture, Multiple-Displacement Amplification, and Real-Time Sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00097-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Noyes, N.R.; Doster, E.; Martin, J.N.; Linke, L.M.; Magnuson, R.J.; Yang, H.; Geornaras, I.; Woerner, D.R.; Jones, K.L.; et al. Use of Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing Technology To Detect Foodborne Pathogens within the Microbiome of the Beef Production Chain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2433–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaguech, M.A.; Bahri, M.; Djebbi, K.; Zhou, D.; Shi, B.; Liang, L.; Komarova, N.; Kuznetsov, A.; Tlili, C.; Wang, D. Nanopore-Based Aptasensor for Label-Free and Sensitive Vanillin Determination in Food Samples. Food Chem. 2022, 389, 133051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.-W.; Huang, L.; Pu, H.; Ma, J. Introducing Reticular Chemistry into Agrochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1070–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont, A.; Andreo, J.; Lanza, A.; Galarda, A.; Macreadie, L.; Wuttke, S.; Canossa, S.; Ploetz, E.; Goscianska, J. Applications of Reticular Diversity in Metal–Organic Frameworks: An Ever-Evolving State of the Art. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 430, 213655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Karimi, M.; Gong, Y.-N.; Dai, N.; Safarifard, V.; Jiang, H.-L. Integration of Metal-Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Matter 2021, 4, 2230–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liao, J.; Wang, D.; Li, G. Fabrication of Gold Nanoparticle-Embedded Metal–Organic Framework for Highly Sensitive Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Detection. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 3955–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J. Facile Regulation of Shell Thickness of the Au@MOF Core-Shell Composites for Highly Sensitive Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Sensing. Sensors 2022, 22, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Vellingiri, K.; Samaddar, P.; Kumar, P.; Deep, A.; Kumar, N. Hybrid Porous Thin Films: Opportunities and Challenges for Sensing Applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 104, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Campbell, M.G.; Dincă, M. Electrically Conductive Porous Metal-Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3566–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Hidalgo Crespo, T.; Permyakova, A.; Sicard, C.; Serre, C.; Chaussé, A.; Steunou, N.; Legrand, L. Design of Metal Organic Framework–Enzyme Based Bioelectrodes as a Novel and Highly Sensitive Biosensing Platform. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8983–8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gao, J.; Tan, H. Integrated Antibody with Catalytic Metal–Organic Framework for Colorimetric Immunoassay. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 25113–25120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempahanumakkagari, S.; Kumar, V.; Samaddar, P.; Kumar, P.; Ramakrishnappa, T.; Kim, K.-H. Biomolecule-Embedded Metal-Organic Frameworks as an Innovative Sensing Platform. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, N.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Bhatt, D.; Tuteja, S.K.; Kim, K.-H.; Deep, A. Highly Sensitive Optical Biosensing of Staphylococcus aureus with an Antibody/Metal–Organic Framework Bioconjugate. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; He, B.; Liang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Wei, M.; Jin, H.; Ren, W.; et al. An Electrochemical Aptasensor Based on Dual-Enzymes-Driven Target Recycling Strategy for Patulin Detection in Apple Juice. Food Control 2022, 137, 108907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, T.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Qian, G. A Manganese-Based Metal-Organic Framework Electrochemical Sensor for Highly Sensitive Cadmium Ions Detection. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 275, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-H.; Liu, D.-X.; Yang, K.-Q.; Dong, S.-J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.-J. A New Cluster-Based Metal-Organic Framework with Triazine Backbones for Selective Luminescent Detection of Mercury(II) Ion. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2018, 90, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Kang, J.; Wu, Y.; Pang, C.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z. Recent Advances in Metal/Covalent Organic Framework-Based Materials for Photoelectrochemical Sensing Applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 157, 116793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Ma, Y.; Hu, B.; He, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, S. Construction of Ce-MOF@COF Hybrid Nanostructure: Label-Free Aptasensor for the Ultrasensitive Detection of Oxytetracycline Residues in Aqueous Solution Environments. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 127, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yang, L.; Men, C.; Xie, Y.F.; Liu, J.J.; Zou, H.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Zhan, L.; Huang, C.Z. Photothermal Soft Nanoballs Developed by Loading Plasmonic Cu 2– x Se Nanocrystals into Liposomes for Photothermal Immunoassay of Aflatoxin B 1. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 4444–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Guo, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J. The Development of Thermal Immunosensing for the Detection of Food-Borne Pathogens E. Coli O157:H7 Based on the Novel Substoichiometric Photothermal Conversion Materials MoO3-x NPs. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 344, 130306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj Pandian, C.; Palanivel, R.; Balasundaram, U. Green Synthesized Nickel Nanoparticles for Targeted Detection and Killing of S. Typhimurium. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 174, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Dong, W.; Zheng, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, R.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lou, Y. Rapid Photothermal Detection of Foodborne Pathogens Based on the Aggregation of MPBA-AuNPs Induced by MPBA Using a Thermometer as a Readout. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 212, 112349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. An Immunofiltration Strip Method Based on the Photothermal Effect of Gold Nanoparticles for the Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Analyst 2019, 144, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heavy Metals | Reference Value | Agency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylmercury | 0.3 μg/kg/day | ATSDR, 1999 | [50] |

| Chromium (III) | 300 μg/kg/day | EFSA, 2014 | [51] |

| Chromium (VI) | 3 μg/kg/day | EPA, 1998 | [52] |

| Lead | 0.16 μg/kg/day | FDA, 2018 | [53] |

| Cadmium | 1 μg/kg/day | EPA, 1989 | [54] |

| Nikel | 2.8 μg/kg/day | EFSA, 2025 | [55] |

| Strontium | 130 μg/kg/day | WHO, 2010 | [56] |

| Zinc | 0.43 μg/kg/day | SCF, 2003 | [56] |

| Iron | 0.8 μg/kg/day | WHO/FAO, 2010 | [56] |

| Palladium | 0.5 μg/kg/day | WHO/FAO, 2010 | [56] |

| Inorganic Arsenic | 0.3 μg/kg/day | ATSDR, 2007 | [50] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nam, N.N.; Do, H.D.K.; Trinh, K.T.L.; Lee, N.Y. Recent Progress in Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Food Monitoring. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12234116

Nam NN, Do HDK, Trinh KTL, Lee NY. Recent Progress in Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Food Monitoring. Nanomaterials. 2022; 12(23):4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12234116

Chicago/Turabian StyleNam, Nguyen Nhat, Hoang Dang Khoa Do, Kieu The Loan Trinh, and Nae Yoon Lee. 2022. "Recent Progress in Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Food Monitoring" Nanomaterials 12, no. 23: 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12234116

APA StyleNam, N. N., Do, H. D. K., Trinh, K. T. L., & Lee, N. Y. (2022). Recent Progress in Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Food Monitoring. Nanomaterials, 12(23), 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12234116