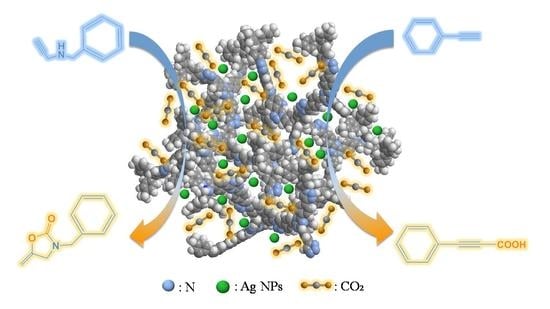

Nitrogen-Rich Porous Organic Polymers with Supported Ag Nanoparticles for Efficient CO2 Conversion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

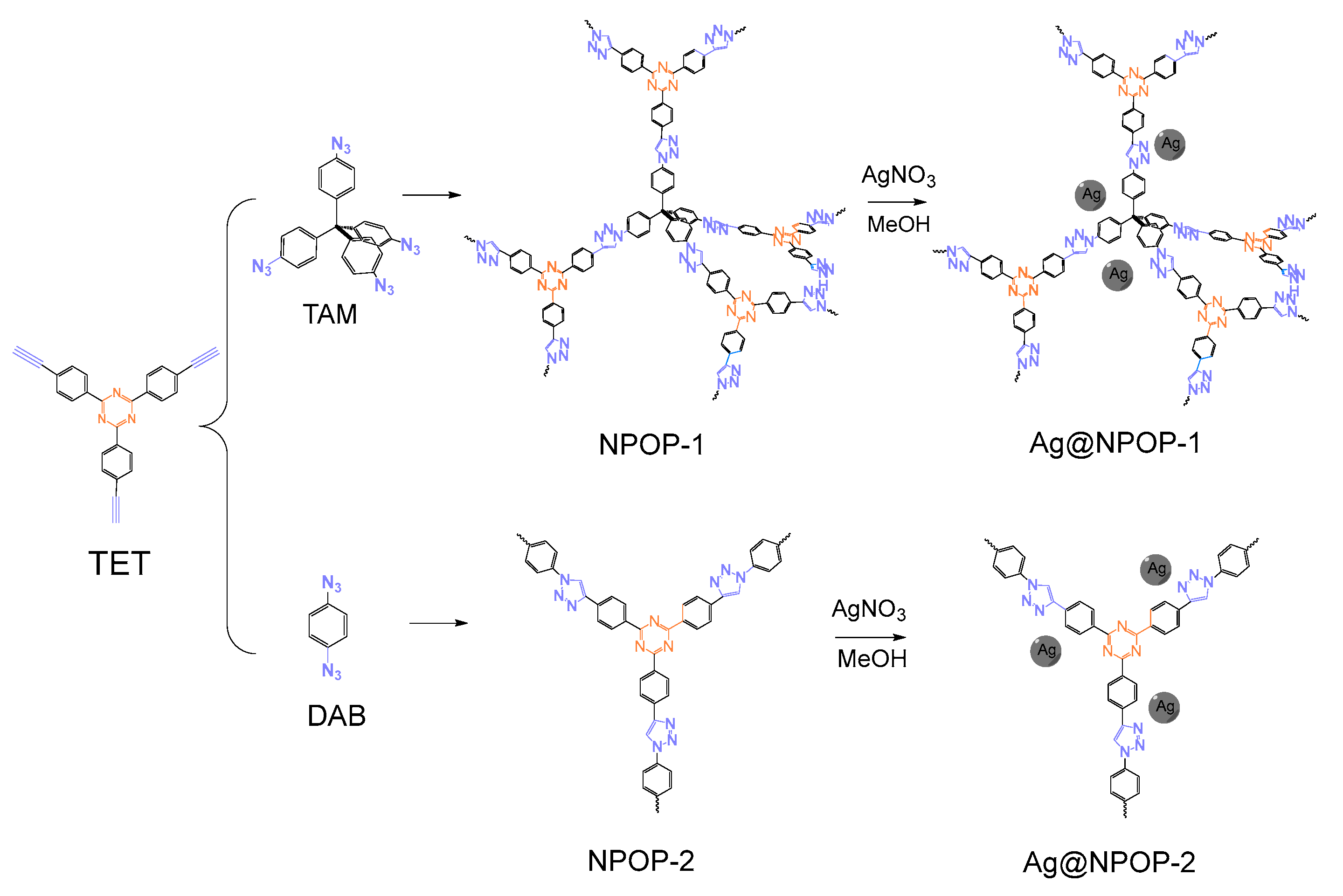

2.1. Synthesis of NPOP-1

2.2. Synthesis of NPOP-2

2.3. Synthesis of Ag@NPOP-1

2.4. Synthesis of Ag@NPOP-2

2.5. Carboxylative Cyclization of Propargylic Amines with CO2

2.6. Carboxylation of Terminal Alkyne

2.7. Recycle Procedure of the Catalyst

3. Results and Discussion

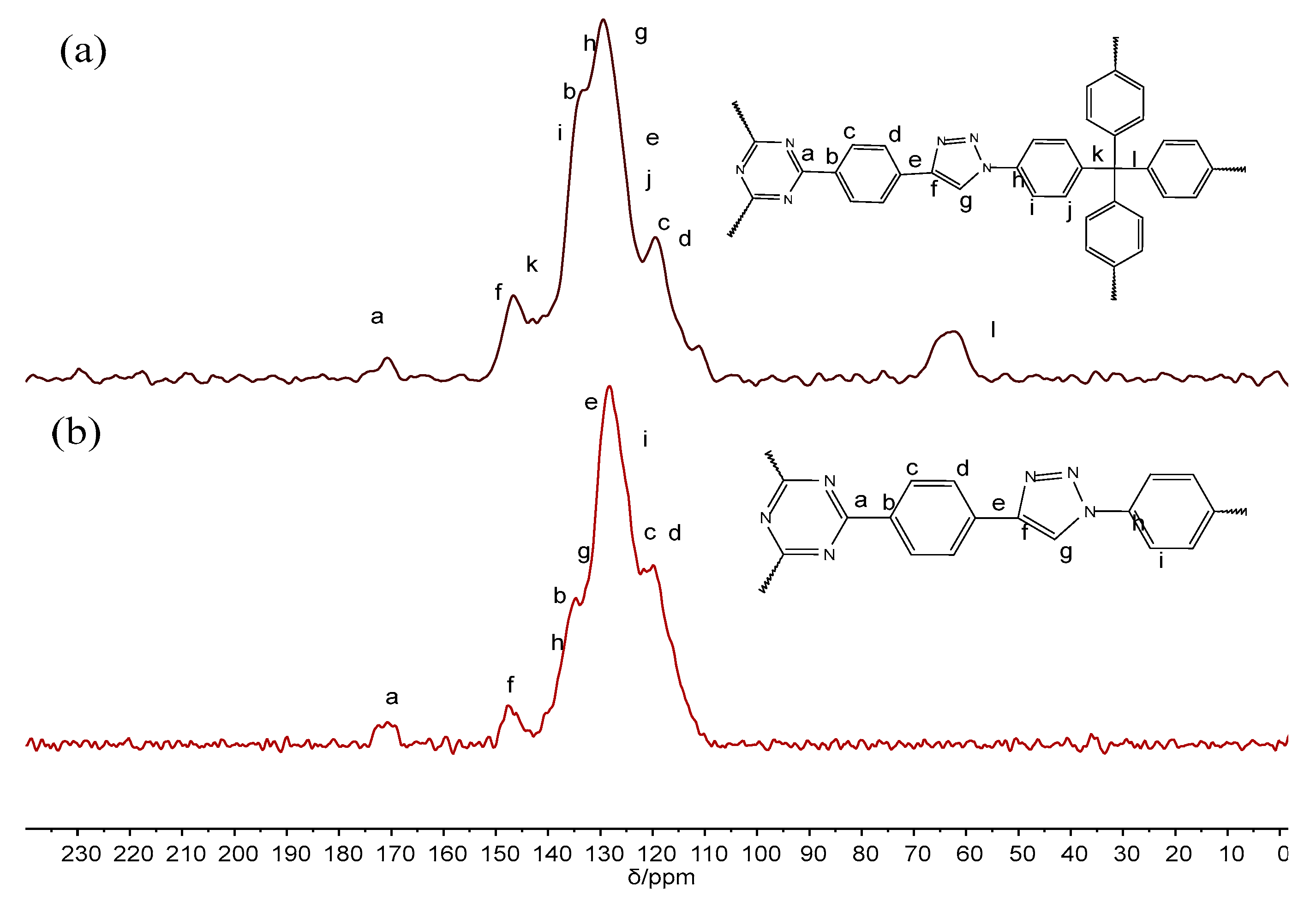

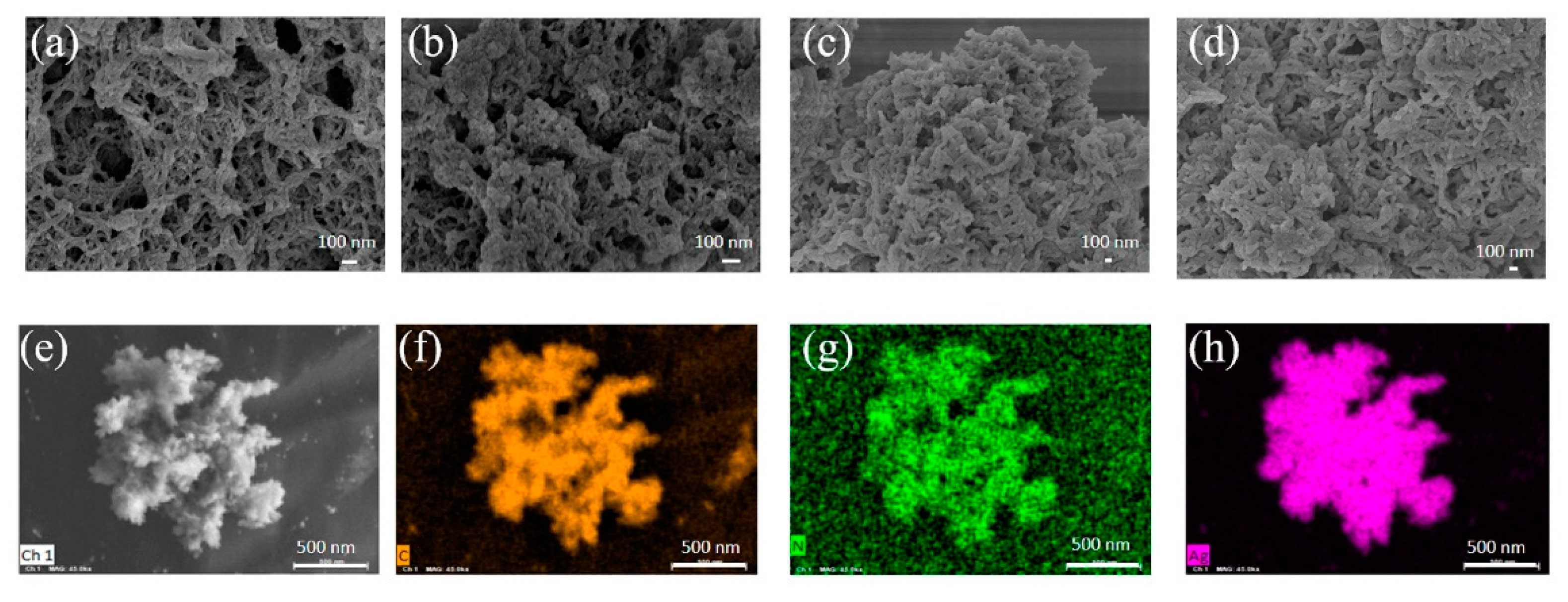

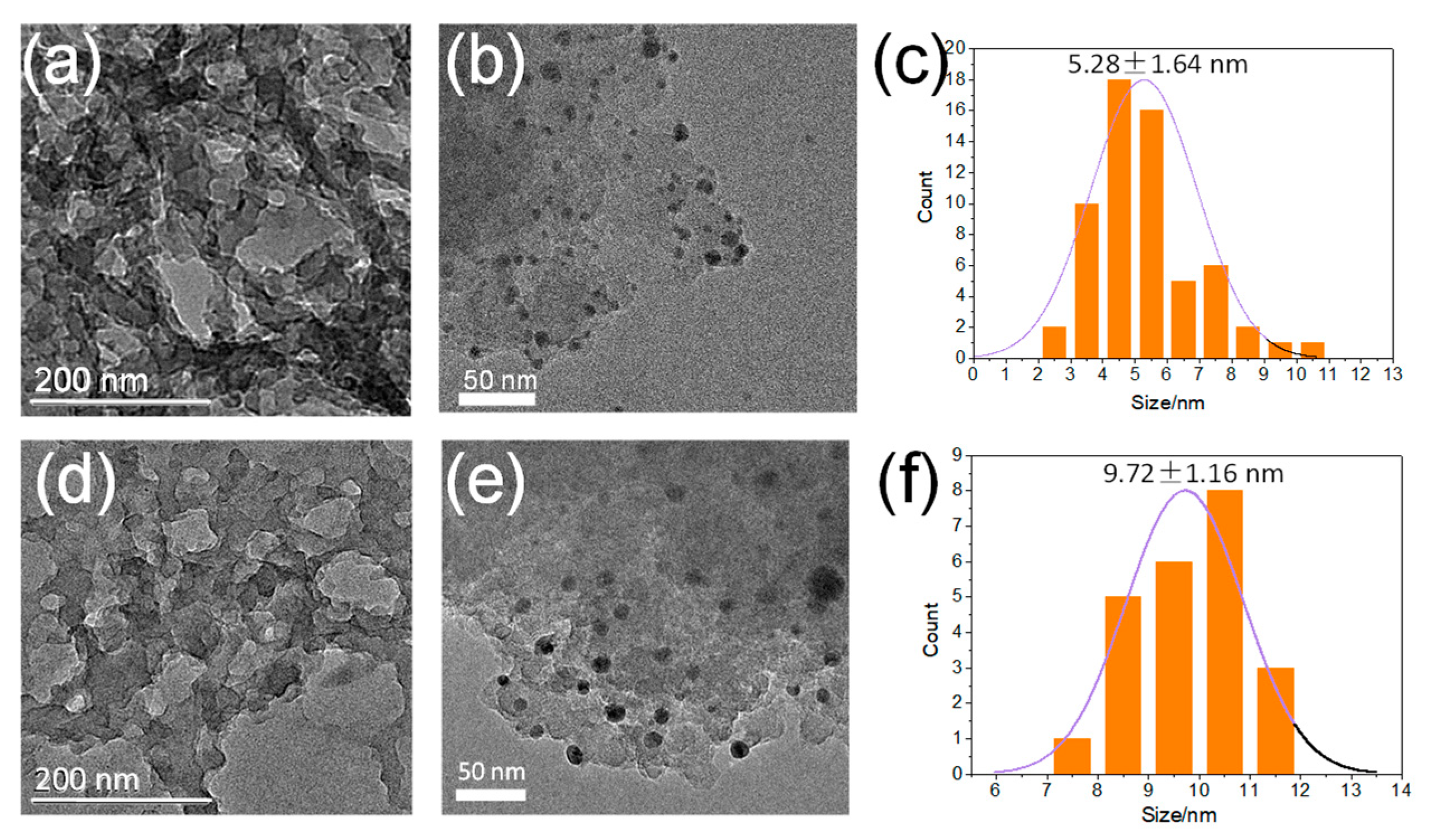

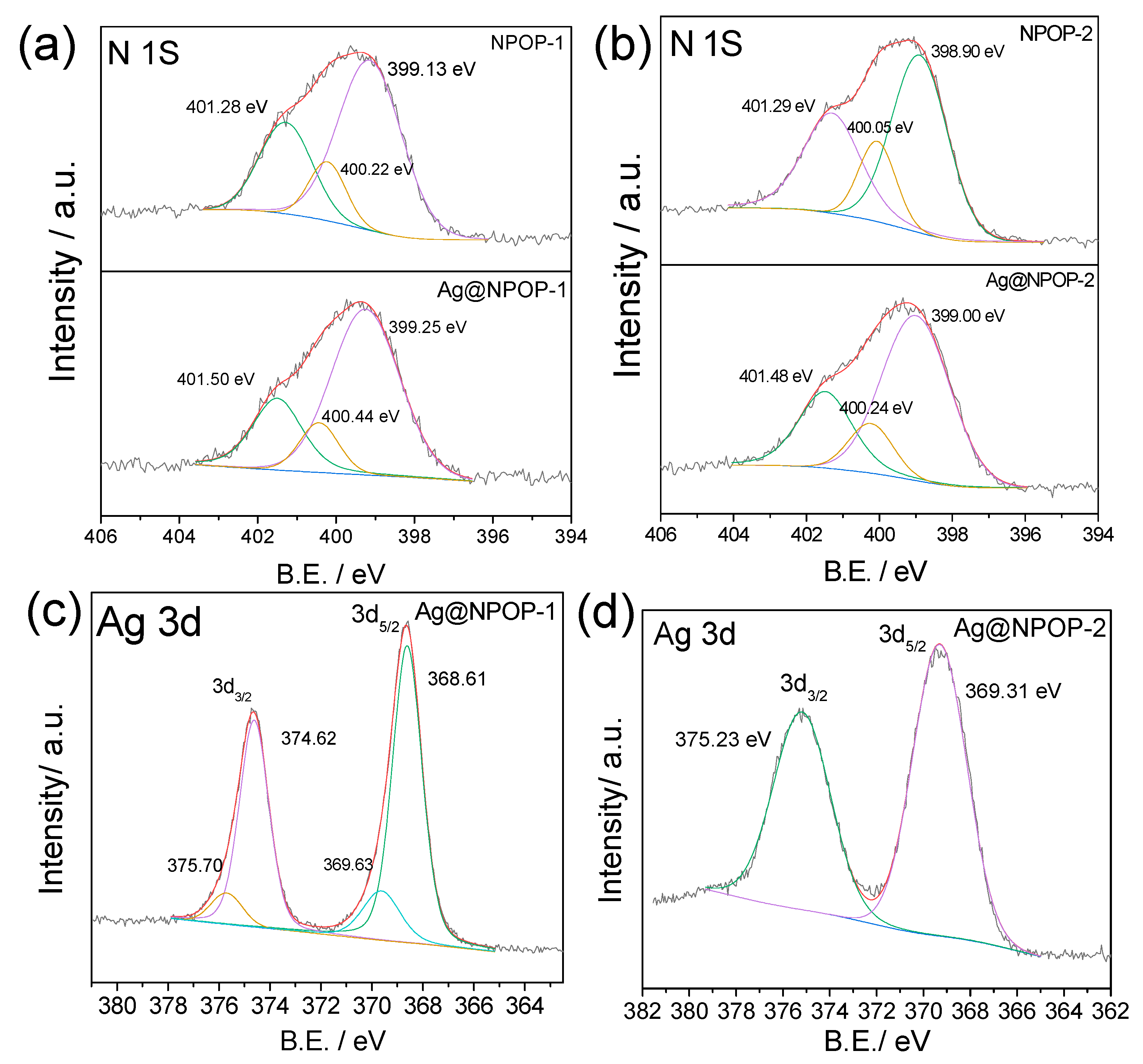

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

3.2. Catalytic Activity of Ag@NPOPs towards CO2 Conversion

3.2.1. Carboxylative Cyclization of Propargylic Amines with CO2

3.2.2. Carboxylation of Phenylacetylene with CO2

3.3. Catalyst Stability

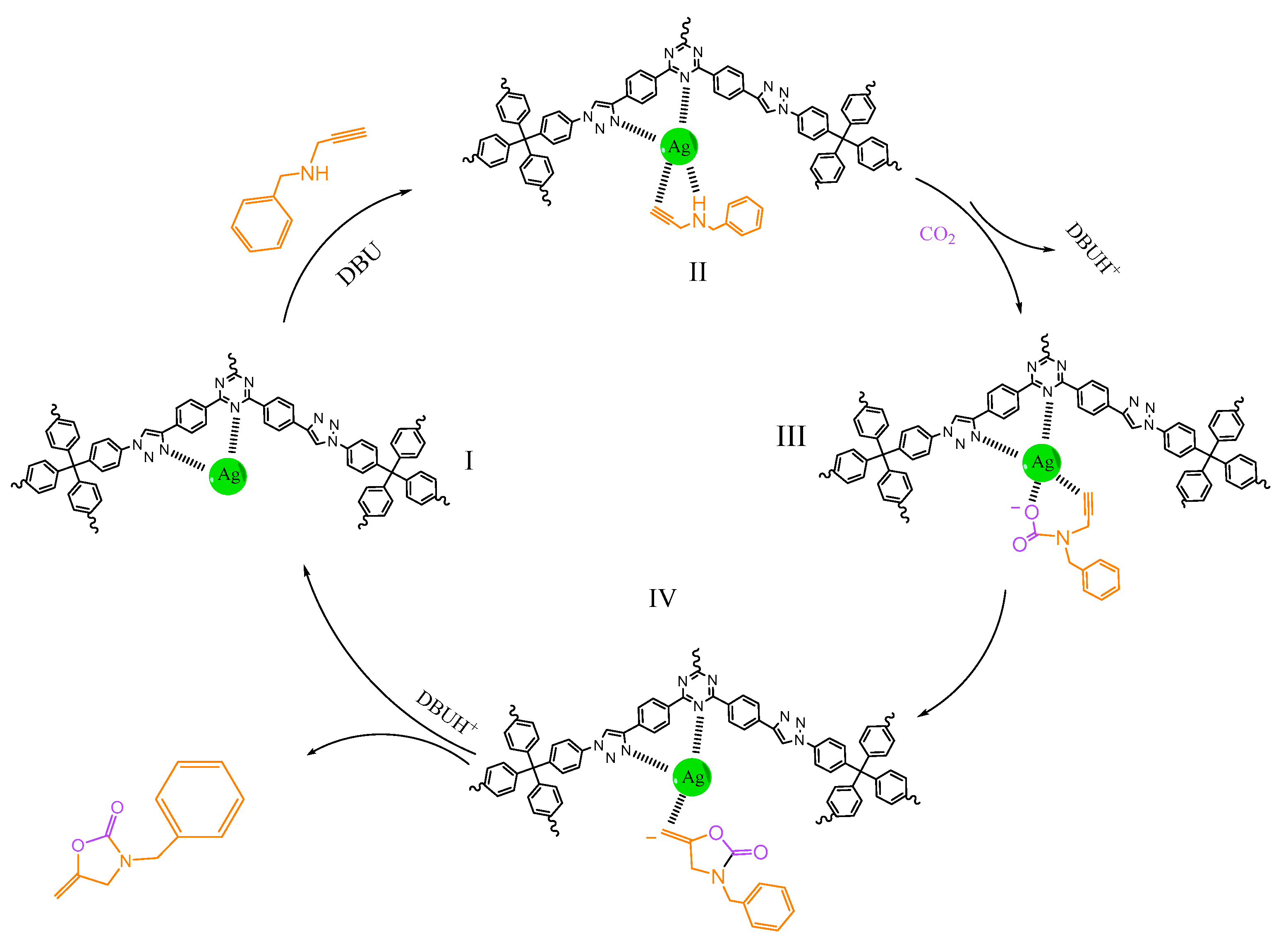

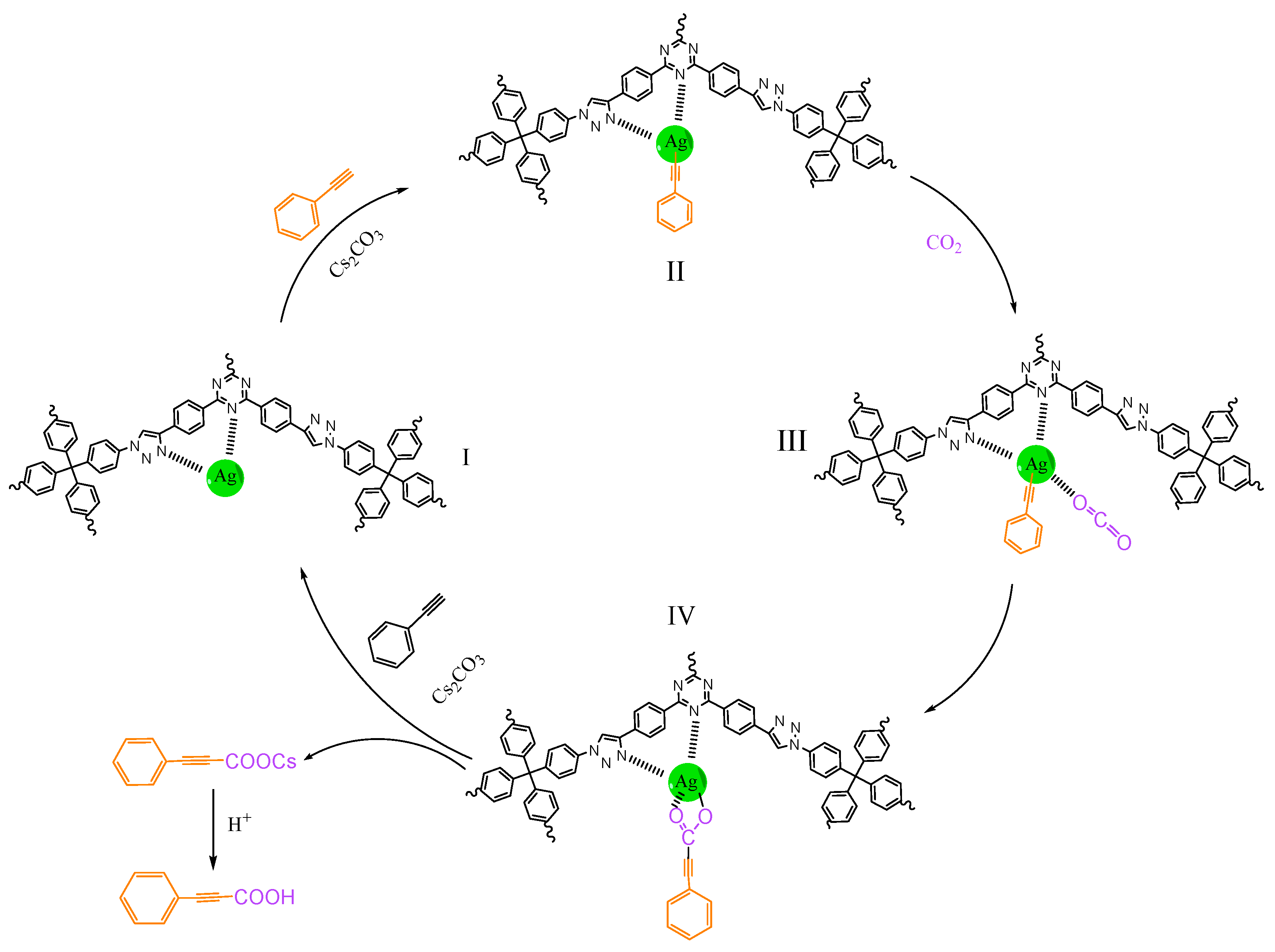

3.4. Catalytic Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mensah, C.N.; Long, X.; Boamah, K.B.; Bediako, I.A.; Dauda, L.; Salman, M. The Effect of Innovation on CO2 Emissions of OCED Countries from 1990 to 2014. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 29678–29698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghussain, L. Global Warming: Review on Driving Forces and Mitigation. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2019, 38, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, C.; Guan, A.; Kan, M.; Zheng, G. Photocatalytic CO2 Conversion: From C1 Products to Multi-carbon Oxygenates. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 10268–10285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdinejad, M.; Tang, K.; Dao, C.; Saedy, S.; Burdyny, T. Immobilization Strategies for Porphyrin-based Molecular Catalysts for the Electroreduction of CO2. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 7626–7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Humayun, M.; Garba, M.D.; Ullah, L.; Zeb, Z.; Helal, A.; Suliman, M.H.; Alfaifi, B.Y.; Iqbal, N.; Abdinejad, M.; et al. Electrochemical Reduction of CO2: A Review of Cobalt Based Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Fuels. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.-X.; He, S.-G. Conversion of CH4 Catalyzed by Gas Phase Ions Containing Metals. Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202200062. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Yang, Z.; Kong, X.; Geng, Z.; Zeng, J. Progresses on Carbon Dioxide Electroreduction into Methane. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhong, H.; Wang, C.; He, D.; Jin, F. CO2 Reduction into Formic Acid under Hydrothermal Conditions: A mini Review. Energy Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1601–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-b.; Yu, C.; Tan, X.-y.; Cui, S.; Zhang, Y.-f.; Qiu, J.-s. Recent Advances in the Electroreduction of Carbon Dioxide to Formic Acid over Carbon-based Materials. New Carbon Mater. 2022, 37, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, T.; Shadangi, K.P.; Sarangi, P.K.; Srivastava, R.K. Conversion of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol: A Comprehensive Review. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shi, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, T. Photodriven CO2 Hydrogenation into Diverse Products: Recent Progress and Perspective. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 5291–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, W.; Xu, X.-Y.; Mao, F.-F.; Shi, L.; Wang, H.-J. N/O-rich Multilayered Ultramicroporous Carbon for Highly Efficient Capture and Conversion of CO2 under Atmospheric Conditions. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 3208–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yuan, D.; Yao, Y. Bifunctional Rare-Earth Metal Catalysts for Conversion of CO2 and Epoxides into Cyclic Carbonates. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202200106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-C.; Zhao, K.-C.; Yao, Y.-Q.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Y. Synergetic Activation of CO2 by the DBU-organocatalyst and Amine Substrates towards Stable Carbamate Salts for Synthesis of Oxazolidinones. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 7072–7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, C.; Gong, Y.; Du, M.; Chen, C.; Chaemchuen, S.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Díaz Velázquez, H.; Yuan, Y.; Verpoort, F. Green Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones by an Efficient and Recyclable CuBr/Ionic Liquid System via CO2, Propargylic Alcohols, and 2-Aminoethanols. Catalysts 2021, 11, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, R.; Zhang, L.; Gao, L.-L.; Sun, W.-J.; Yang, S.-L.; Gao, E.-Q. Copper(I)-Modified Covalent Organic Framework for CO2 Insertion to Terminal Alkynes. Mol. Catal. 2021, 499, 111319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, N.; Wei, W. SiO2-Coated Ag Nanoparticles for Conversion of Terminal Alkynes to Propolic Acids via CO2 Insertion. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 7107–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Köhler, B.; Kuckshinrichs, W.; Leitner, W.; Markewitz, P.; Müller, T.E. Chemical Technologies for Exploiting and Recycling Carbon Dioxide into the Value Chain. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 1216–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Guo, L.; Cui, Y.; Yang, G.; He, Y.; Zeng, C.; Taguchi, A.; Abe, T.; Ma, Q.; Yoneyama, Y.; et al. Selective Conversion of CO2 into Para-Xylene over a ZnCr2O4-ZSM-5 Catalyst. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 6541–6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhari, N.J.; Nurdini, N.; Mardiana, S.; Ilmi, T.; Fajar, A.T.N.; Makertihartha, I.G.B.N.; Subagjo; Kadja, G.T.M. Zeolite-based Catalyst for Direct Conversion of CO2 to C2+ Hydrocarbon: A Review. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 59, 101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-R.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.-F.; Guan, P.-X.; Wang, R.; Xu, B.-H. Immobilization Poly(ionic liquid)s into Hierarchical Porous Covalent Organic Frameworks as Heterogeneous Catalyst for Cycloaddition of CO2 with Epoxides. Mol. Catal. 2022, 520, 112164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.; Wu, D.; Pan, H.; Zhao, T.; Hu, X. Imidazolium Hydrogen Carbonate Ionic Liquids: Versatile Organocatalysts for Chemical Conversion of CO2 into Valuable Chemicals. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 39, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Vasiliades, M.A.; Huang, L.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, B.; et al. Unravelling the Mechanism of Intermediate-Temperature CO2 Interaction with Molten-NaNO3-Salt-Promoted MgO. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Park, J.; Yoo, Y. Formation and Polymorph Transformation trends of Metal Carbonate in Inorganic CO2 Conversion Process Using Simulated Brine: Study for Post-treatment of Industrial brine via CO2Conversion. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 162, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Qu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, P.; Sun, J. A Facile Fabrication of a Multi-functional and Hierarchical Zn-based MOF as an Efficient Catalyst for CO2Fixation at Room-temperature. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 3085–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, P.; Sun, J. Facile One-Pot Synthesis of Zn/Mg-MOF-74 with Unsaturated Coordination Metal Centers for Efficient CO2 Adsorption and Conversion to Cyclic Carbonates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 61334–61345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liao, J.-P.; Yang, M.-Y.; Cai, Y.-P.; Li, S.-L.; Lan, Y.-Q. Covalent Organic Framework Based Functional Materials: Important Catalysts for Efficient CO2 Utilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, M.; Lei, K.; Xie, H.; et al. Photocatalytic CO2Conversion over Single-atom MoN2Sites of Covalent Organic Framework. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 291, 120146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Bian, Y.; Lv, H.; Qiu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, R.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, S.; Li, D.; et al. A Novel Conjugated Microporous Polymer Microspheres Comprising Cobalt Porphyrins for Efficient catalytic CO2 Cycloaddition under Ambient Conditions. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 58, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ouyang, H.; Tan, B. Porous Organic Polymers for Catalytic Conversion of Carbon Dioxide. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 3833–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, P.; Antonietti, M.; Thomas, A. Porous, Covalent Triazine-Based Frameworks Prepared by Ionothermal Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3450–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, H.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Cai, D.; Qin, P.; Baeyens, J. Triazine-based N-rich Porous Covalent Organic Polymer for the Effective Detection and Removal of Hg(II) from an Aqueous Solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 130757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.-Q.; Zeng, G.; You, Z.-X.; Wang, C.; Sun, L.-X.; Bai, F.-Y.; Xing, Y.-H. Cu(ii) and Zn(ii) Frameworks Constructed by Directional Tuning of Diverse Substituted Groups on a Triazine Skeleton and Supermassive Adsorption Behavior for Lodine and Dyes. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 5457–5470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, C. Robust Carbazole-based Covalent Triazine Frameworks with Defective Ultramicropore Structure for Efficient Ethane-selective Ethane-ethylene Separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Q.; Lu, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Guo, S.; Han, F. Covalent Triazine Frameworks for the Dynamic Adsorption/Separation of Benzene/Cyclohexane Mixtures. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 7580–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.G.; El-Mahdy, A.F.M.; Takashi, Y.; Kuo, S.-W. Ultrastable Conductive Microporous Covalent Triazine Frameworks based on Pyrene Moieties Provide High-performance CO2 Uptake and Supercapacitance. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 8241–8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, T.; Yang, G.; Yang, C.; Huang, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, J. Synthesis of biphenyl-linked Covalent Triazine Frameworks with Excellent Lithium Storage Performance as Anode in Lithium Ion Battery. J. Power Sources 2022, 523, 231041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Lin, G.; Niu, Q.; Bi, J.; Wu, L. Covalent Triazine-based Frameworks Confining Cobalt Single Atoms for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction and Hydrogen Production. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 116, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, S.; Cen, W.; Cao, X.; Qiao, S.; Han, B.-H. Pristine, Metal ion and Metal Cluster Modified Conjugated Triazine Frameworks as Electrocatalysts for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 10146–10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Tan, B. Three-Dimensional Crystalline Covalent Triazine Frameworks via a Polycondensation Approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202117668. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Yang, J.; Wei, S.; Bi, S.; Xia, Y.; Chen, M.; Hou, Y.; Qiu, M.; Yuan, C.; Su, Y.; et al. Atomic Ni Anchored Covalent Triazine Framework as High Efficient Electrocatalyst for Carbon Dioxide Conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1806884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.-C.; Wu, J.-K.; Lu, J.; Yu, G.-X.; Zhu, R.-R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.-Q.; Sun, L.-B. Underlying Mechanism of CO2 Adsorption onto Conjugated Azacyclo-copolymers: N-doped Adsorbents Capture CO2Chiefly through Acid–base Interaction? J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 17842–17853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Fei, H.; Ma, J.; Liu, F. Rational Self-assembly of Triazine- and Urea-functionalized Periodic Mesoporous Organosilicas for Efficient CO2 Adsorption and Conversion into Cyclic Carbonates. Fuel 2022, 315, 123230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Wang, W.; Li, F. Building N-Heterocyclic Carbene into Triazine-Linked Polymer for Multiple CO2 Utilization. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 5996–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Du, C.; Cao, L.; She, T.; Li, Y.; Bai, G. Ultrafine Ag Nanoparticles Encapsulated by Covalent Triazine Framework Nanosheets for CO2 Conversion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 38953–38962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, Y.; Luan, T.-X.; Cheng, K.; Li, C.; Li, P.-Z. Facile Construction of a Click-based Robust Porous Organic Polymer and its In-situ Sulfonation for Proton Conduction. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2021, 325, 111348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiariol, L.; Chaix, C.; Farre, C.; Moreau, E. Click and Bioorthogonal Chemistry: The Future of Active Targeting of Nanoparticles for Nanomedicines? Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 340–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hu, R.; Qin, A.; Tang, B.Z. Copper-based Ionic Liquid-catalyzed Click Polymerization of Diazides and Diynes toward Functional Polytriazoles for Sensing Applications. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 2006–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B. Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Yang, H.-S.; Lee, I.-H.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, H.J.; Son, S.U. Valorization of Click-Based Microporous Organic Polymer: Generation of Mesoionic Carbene–Rh Species for the Stereoselective Synthesis of Poly(arylacetylene)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 4100–4105. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, R. Facile Fabrication of Ultrafine Palladium Nanoparticles with Size- and Location-Control in Click-Based Porous Organic Polymers. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 5352–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Su, Q.; Ju, P.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Wu, Q.; Yang, B. A Hydrophilic Covalent Organic Framework for Photocatalytic Oxidation of Benzylamine in Water. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, H.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Yang, J.; Jia, X.; Yang, H.; Hu, W.; Wen, K. Pillar[5]Arene Based Conjugated Macrocycle Polymers with Unique Photocatalytic Selectivity. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 3225–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkebiel, A.; Beyer, O.; Lüning, U. Substituted 1,3,5-Triazine Hexacarboxylates as Potential Linkers for MOFs. Molecules 2019, 24, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Choi, H.M.; Lee, S.J. Cu(ii)Cl2 Containing Bispyridine-based Porous Organic Polymer Support Prepared via Alkyne–azide Cycloaddition as a Heterogeneous Catalyst for Oxidation of Various Olefins. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 9149–9152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiki, A.A.; Takale, B.S.; Telvekar, V.N. One Pot Synthesis of Aromatic Azide Using Sodium Nitrite and Hydrazine Hydrate. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 1294–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-R.; Duan, W.-G.; Li, D.-P. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Rich Polymers by Click Polymerization Reaction and Gas Sorption Property. Molecules 2018, 23, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Liu, H. Triazine-Functionalized Silsesquioxane-Based Hybrid Porous Polymers for Efficient Photocatalytic Degradation of Both Acidic and Basic Dyes under Visible Light. ChemCatChem 2021, 13, 5178–5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Farha, O.K.; Spokoyny, A.M.; Mirkin, C.A.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Hupp, J.T.; Nguyen, S.T. A “Click-based” Porous Organic Polymer from Tetrahedral Building Blocks. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 1700–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.-T.; Yang, X.-Y.; Liu, S.-X.; Miao, Y.-X.; Zhao, Z. Highly Dispersed Silver Nanoparticles Supported on a Hydroxyapatite Catalyst with Different Morphologies for CO Oxidation. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 6940–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, D.-P.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, Q.; Luque, R. Enhanced Catalytic Benzene Oxidation over a Novel Waste-derived Ag/eggshell Catalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 8832–8844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Das, M.; Manna, A.; Krishna, R.; Das, S. Newly Designed 1,2,3-triazole Functionalized Covalent Triazine Frameworks with Exceptionally High Uptake Capacity for both CO2 and H2. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, X.; Yan, F.; He, X.; Wang, J.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.; Chen, L.; Bai, G. Controllable Encapsulation of Silver Nanoparticles by Porous Pyridine-based Covalent Organic Frameworks for Efficient CO2 Conversion using Propargylic Amines. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Du, J.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Meng, X.; Song, X.; Liang, Z.; Yan, W. Boosting Selective C2H2/CH4, C2H4/CH4 and CO2/CH4 Adsorption Performance via 1,2,3-triazole Functionalized Triazine-based Porous Organic Polymers. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 42, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthiaraj, P.; Kim, H.S.; Yu, K.; Ahn, W.-S. Triphenylamine-based Covalent Imine Framework for CO2 Capture and Catalytic Conversion into Cyclic Carbonates. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 297, 110011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, N.; Homburg, T.; Stock, N.; Senker, J. Porous Imine-based Networks with Protonated Imine Linkages for Carbon Dioxide Separation from Mixtures with Nitrogen and Methane. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 18492–18504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Wang, D.-Y.; Wang, W.-J. Post-Functionalization of Hydroxyl-Appended Covalent Triazine Framework via Borrowing Hydrogen Strategy for Effective CO2 Capture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 292, 109765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; He, X.; Pan, C.; Yan, J.; Yu, G. Functionalized Covalent Triazine Frameworks for Effective CO2 and SO2 Removal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 36002–36009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Yan, J.; Liu, C.; Pan, C.; Yu, G. Acid/Hydrazide-Appended Covalent Triazine Frameworks for Low-pressure CO2 Capture: Pre-designable or Post-synthesis Modification. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 21266–21274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Su, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, R. Imidazolium- and Triazine-Based Porous Organic Polymers for Heterogeneous Catalytic Conversion of CO2 into Cyclic Carbonates. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 4855–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, B.; Yan, J.; Wang, Z. Micro- and Mesoporous Poly(Schiff-base)s Constructed from Different Building Blocks and Their Adsorption Behaviors Towards Organic Vapors and CO2 Gas. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 18881–18888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahdy, A.F.M.; Kuo, C.-H.; Alshehri, A.; Young, C.; Yamauchi, Y.; Kim, J.; Kuo, S.-W. Strategic Design of Triphenylamine- and Triphenyltriazine-based Two-dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks for CO2 Uptake and Energy Storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 19532–19541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jin, S.; Xu, H.; Nagai, A.; Jiang, D. Conjugated Microporous Polymers: Design, Synthesis and Application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8012–8031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, L.; Yu, T.; Zhai, D.; Zhao, W.; Deng, W.-q. Bifunctional poly(ionic liquid) Catalyst with Dual-active-center for CO2 Conversion: Synergistic Effect of Triazine and Imidazolium Motifs. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 54, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, W.; Zhang, S.; Yao, C.; Xu, Y. Porous Cationic Covalent Triazine-Based Frameworks as Platforms for Efficient CO2 and Iodine Capture. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 3259–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Baek, S.B.; Lee, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Triazine-Based Microporous Polymers for Selective Adsorption of CO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 5395–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neti, V.S.P.K.; Wu, X.; Deng, S.; Echegoyen, L. Selective CO2 Capture in An Imine Linked Porphyrin Porous Polymer. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 4566–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbani, M.G.; Sekizkardes, A.K.; Kahveci, Z.; Reich, T.E.; Ding, R.; El-Kaderi, H.M. A 2D Mesoporous Imine-Linked Covalent Organic Framework for High Pressure Gas Storage Applications. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3324–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Dawson, R.; Laybourn, A.; Jiang, J.-x.; Khimyak, Y.; Adams, D.J.; Cooper, A.I. Functional Conjugated Microporous Polymers: From 1,3,5-benzene to 1,3,5-triazine. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wen, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhao, R.; Yang, S. Pre-carbonized Nitrogen-rich Polytriazines for The Controlled Growth of Silver nanoparticles: Catalysts for Enhanced CO2 Chemical Conversion at Atmospheric Pressure. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 3119–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.; Guo, L.; Li, J.; Pan, S.; Bian, C.; Wang, L.; Hu, X.; Meng, X.; et al. A Hierarchical Bipyridine-Constructed Framework for Highly Efficient Carbon Dioxide Capture and Catalytic Conversion. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Chai, S.; Tian, C.; Fulvio, P.F.; Han, K.S.; Hagaman, E.W.; Veith, G.M.; Mahurin, S.M.; Brown, S.; Liu, H.; et al. Synthesis of Porous, Nitrogen-Doped Adsorption/Diffusion Carbonaceous Membranes for Efficient CO2 Separation. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013, 34, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yang, X.; Ye, X.; Duan, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B.; Huang, Y. Knitting Aryl Network Polymers-Incorporated Ag Nanoparticles: A Mild and Efficient Catalyst for the Fixation of CO2 as Carboxylic Acid. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 9634–9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Liang, Z.; Liu, B.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Phenylamino-, Phenoxy-, and Benzenesulfenyl-Linked Covalent Triazine Frameworks for CO2 Capture. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 2889–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, P.; Modak, A.; Bhaumik, A. Porous Organic Polymers for Storage and Conversion Reactions. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, J.; Fréchet, J.M.J.; Svec, F. Nanoporous Polymers for Hydrogen Storage. Small 2009, 5, 1098–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, J.-H.; Wu, D.-S.; Zhou, Y.-Q.; Yu, D.-G. Synthesis of Oxazolidin-2-ones from Unsaturated Amines with CO2 by Using Homogeneous Catalysis. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 2292–2306. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xu, H.; Hou, S.-L.; Zhao, B. Eco-friendly Co-catalyst-free Cycloaddition of CO2 and Aziridines Activated by a Porous MOF Catalyst. Sci. China Chem. 2021, 64, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singudas, R.; Reddy, N.C.; Rai, V. Sensitivity Booster for Mass Detection Enables Unambiguous Analysis of Peptides, Proteins, Antibodies, and Protein Bioconjugates. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 9979–9982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjolinho, F.; Arndt, M.; Gooßen, K.; Gooßen, L.J. Catalytic C–H Carboxylation of Terminal Alkynes with Carbon Dioxide. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 2014–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovskiy, A.V.; Larock, R.C. Intermolecular C−O Addition of Carboxylic Acids to Arynes. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 3117–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.S.; Biswas, S.; Ali Molla, R.; Yasmin, N.; Islam, S.M. Green Synthesized AgNPs Embedded in COF: An Efficient Catalyst for the Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones and α-Alkylidene Cyclic Carbonates via CO2 Fixation. ChemNanoMat 2020, 6, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, R.; Biswas, S.; Biswas, I.H.; Riyajuddin, S.; Haque, N.; Ghosh, K.; Islam, S.M. Cu-NPs@COF: A Potential Heterogeneous Catalyst for CO2Fixation to Produce 2-Oxazolidinones as Well as Benzimidazoles under Moderate Reaction Conditions. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 40, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Riyajuddin, S.; Sarkar, S.; Ghosh, K.; Islam, S.M. Pd NPs Decorated on POPs as Recyclable Catalysts for the Synthesis of 2-Oxazolidinones from Propargylic Amines via Atmospheric Cyclizative CO2 Incorporation. ChemNanoMat 2020, 6, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-M.; Qi, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.-J.; Hou, C.-Y.; Li, W.; Wang, L.-J. Copper/DTBP-Promoted Oxyselenation of Propargylic Amines with Diselenides and CO2: Synthesis of Selenyl 2-Oxazolidinones. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 10924–10933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.-Y.; Song, Q.-W.; Ma, R.; Xie, J.-N.; He, L.-N. Efficient Conversion of Carbon Dioxide at Atmospheric Pressure to 2-Oxazolidinones Promoted by Bifunctional Cu(ii)-Substituted Polyoxometalate-Based Ionic Liquids. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, K.-H.; Zhou, Z.-H.; He, L.-N. Reduced Graphene Oxide Supported Ag Nanoparticles: An Efficient Catalyst for CO2 Conversion at Ambient Conditions. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 4825–4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-H.; Xia, S.-M.; Huang, S.-Y.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Chen, K.-H.; He, L.-N. Cobalt-Based Catalysis for Carboxylative Cyclization of Propargylic Amines with CO2 at Atmospheric Pressure. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Molla, R.A.; Kayal, U.; Bhaumik, A.; Islam, S.M. Ag NPs Decorated on a COF in the Presence of DBU as an Efficient Catalytic System for the Synthesis of Tetramic Acids via CO2 Fixation into Propargylic Amines at Atmospheric Pressure. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 4657–4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, M.-Y.; Wang, S.-Y.; Wang, Q.; He, L.-N. In Situ Generated Zinc(II) Catalyst for Incorporation of CO2 into 2-Oxazolidinones with Propargylic Amines at Atmospheric Pressure. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunel, P.; Monot, J.; Kefalidis, C.E.; Maron, L.; Martin-Vaca, B.; Bourissou, D. Valorization of CO2: Preparation of 2-Oxazolidinones by Metal–Ligand Cooperative Catalysis with SCS Indenediide Pd Complexes. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2652–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Jing, X.; He, C.; Liu, X.; Duan, C. Silver Clusters as Robust Nodes and π–Activation Sites for the Construction of Heterogeneous Catalysts for the Cycloaddition of Propargylamines. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, A.; Riyajuddin, S.; Sarkar, S.; Chowdhury, A.H.; Ghosh, K.; Islam, S.M. Silver Nanoparticles Architectured HMP as a Recyclable Catalyst for Tetramic Acid and Propiolic Acid Synthesis through CO2 Capture at Atmospheric Pressure. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Li, Q.; Cao, L.; Du, C.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.; Bai, G. Rebuilding Supramolecular Aggregates to Porous Hollow N-Doped Carbon Tube Inlaid with Ultrasmall Ag Nanoparticles: A Highly Efficient Catalyst for CO2 Conversion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 508, 145220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, L.; Wei, W. Nitrogen-Doped Mesoporous Carbon Single Crystal-Based Ag Nanoparticles for Boosting Mild CO2 Conversion with Terminal Alkynes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 627, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Mei, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, P.; Wu, H.; He, M. Size-Controlled Growth of Silver Nanoparticles onto Functionalized Ordered Mesoporous Polymers for Efficient CO2 Upgrading. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 44241–44248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, N.; Hu, D.; Shen, Q.; Mao, F.; Gao, Q.; Wei, W. Facile and Rapid Preparation of Ag@ZIF-8 for Carboxylation of Terminal Alkynes with CO2 in Mild Conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 28858–28867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.J.; Sharma, A.S.; Shah, A.P.; Sharma, V.S.; Athar, M.; Soni, J.Y. Fixation of CO2 as a Carboxylic Acid Precursor by Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) Supported Ag NPs: A More Efficient, Sustainable, Biodegradable and Eco-Friendly Catalyst. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 8669–8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-H.; Ma, J.-G.; Niu, Z.; Yang, G.-M.; Cheng, P. An Efficient Nanoscale Heterogeneous Catalyst for the Capture and Conversion of Carbon Dioxide at Ambient Pressure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kan, J.-L.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y.-B. Synthesis and Catalytic Properties of Metal–N-Heterocyclic-Carbene-Decorated Covalent Organic Framework. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 7363–7368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.-S.; Xia, S.-M.; Song, Z.-J.; Xu, H.; Shi, Y.; He, L.-N.; Cheng, P.; Zhao, B. Highly Efficient Conversion of Propargylic Amines and CO2 Catalyzed by Noble-Metal-Free [Zn116] Nanocages. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8586–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Li, Y.; Du, C.; She, T.; Li, Q.; Bai, G. Porous Carbon Nitride Frameworks Derived from Covalent Triazine Framework Anchored Ag Nanoparticles for Catalytic CO2 Conversion. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8560–8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.-Y.; Young, D.J.; Ren, Z.-G.; Li, H.-X. Synthesis of a Pyrazole-Based Microporous Organic Polymer for High-Performance CO2 Capture and Alkyne Carboxylation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 4512–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| |||||||

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | T/°C | Base | Time/h | Yield/% | TOF/h−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | \ | CH3CN | 50 | DBU | 2 | N.A. | |

| 2 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 50 | DBU | 2 | 97.0 | 1125.1 |

| 3 | Ag@NPOP-2 | CH3CN | 50 | DBU | 2 | 93.0 | 777.6 |

| 4 | NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 50 | DBU | 2 | N.A. | |

| 5 | NPOP-2 | CH3CN | 50 | DBU | 2 | N.A. | |

| 6 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 50 | \ | 2 | N.A. | |

| 7 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 50 | DBU | 2 | 58 | 672.7 |

| 8 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMF | 50 | DBU | 2 | 42 | 487.2 |

| 9 | Ag@NPOP-1 | EtOH | 50 | DBU | 2 | 15 | 174.0 |

| 10 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 50 | Cs2CO3 | 2 | 4.0 | 46.4 |

| 11 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 50 | K2CO3 | 2 | 2.0 | 23.2 |

| 12 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 50 | NaOH | 2 | N.A. | |

| 13 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 40 | DBU | 2 | 86.0 | 997.5 |

| 14 | Ag@NPOP-1 | CH3CN | 30 | DBU | 2 | 40.0 | 464.0 |

| |||||||

| Entry | Catalyst | Solvent | T/°C | Base (Amount/mmol) | Time /h | Yield/% | TOF /h−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ag@NPOP-2 | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 92.1 | 64.2 |

| 2 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 94.0 | 90.9 |

| 3 | NPOP-2 | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 51.2 | |

| 4 | NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 55.4 | |

| 5 | Ag@NPOP-1 b | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 94.2 | 36.4 |

| 6 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMF | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 73.7 | 71.2 |

| 7 | Ag@NPOP-1 | ACN | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 11.9 | 11.5 |

| 8 | Ag@NPOP-1 | EtOH | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| 9 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | K2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 11.5 | 11.1 |

| 10 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | DBU(0.6) | 12 | 51.0 | 49.3 |

| 11 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | NaOH (0.6) | 12 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| 12 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.4) | 12 | 60.8 | 58.8 |

| 13 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 60 | Cs2CO3(0.2) | 12 | 24.5 | 23.7 |

| 14 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 50 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 65.2 | 63.0 |

| 15 | Ag@NPOP-1 | DMSO | 40 | Cs2CO3(0.6) | 12 | 18.0 | 17.4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Ma, S.; Cui, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J. Nitrogen-Rich Porous Organic Polymers with Supported Ag Nanoparticles for Efficient CO2 Conversion. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12183088

Wu J, Ma S, Cui J, Yang Z, Zhang J. Nitrogen-Rich Porous Organic Polymers with Supported Ag Nanoparticles for Efficient CO2 Conversion. Nanomaterials. 2022; 12(18):3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12183088

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jinyi, Shasha Ma, Jiawei Cui, Zujin Yang, and Jianyong Zhang. 2022. "Nitrogen-Rich Porous Organic Polymers with Supported Ag Nanoparticles for Efficient CO2 Conversion" Nanomaterials 12, no. 18: 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12183088

APA StyleWu, J., Ma, S., Cui, J., Yang, Z., & Zhang, J. (2022). Nitrogen-Rich Porous Organic Polymers with Supported Ag Nanoparticles for Efficient CO2 Conversion. Nanomaterials, 12(18), 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12183088