Hydrogen Gas Sensing Performances of p-Type Mn3O4 Nanosystems: The Role of Built-in Mn3O4/Ag and Mn3O4/SnO2 Junctions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Material Characterization

2.3. Gas Sensing Tests

3. Results and Discussion

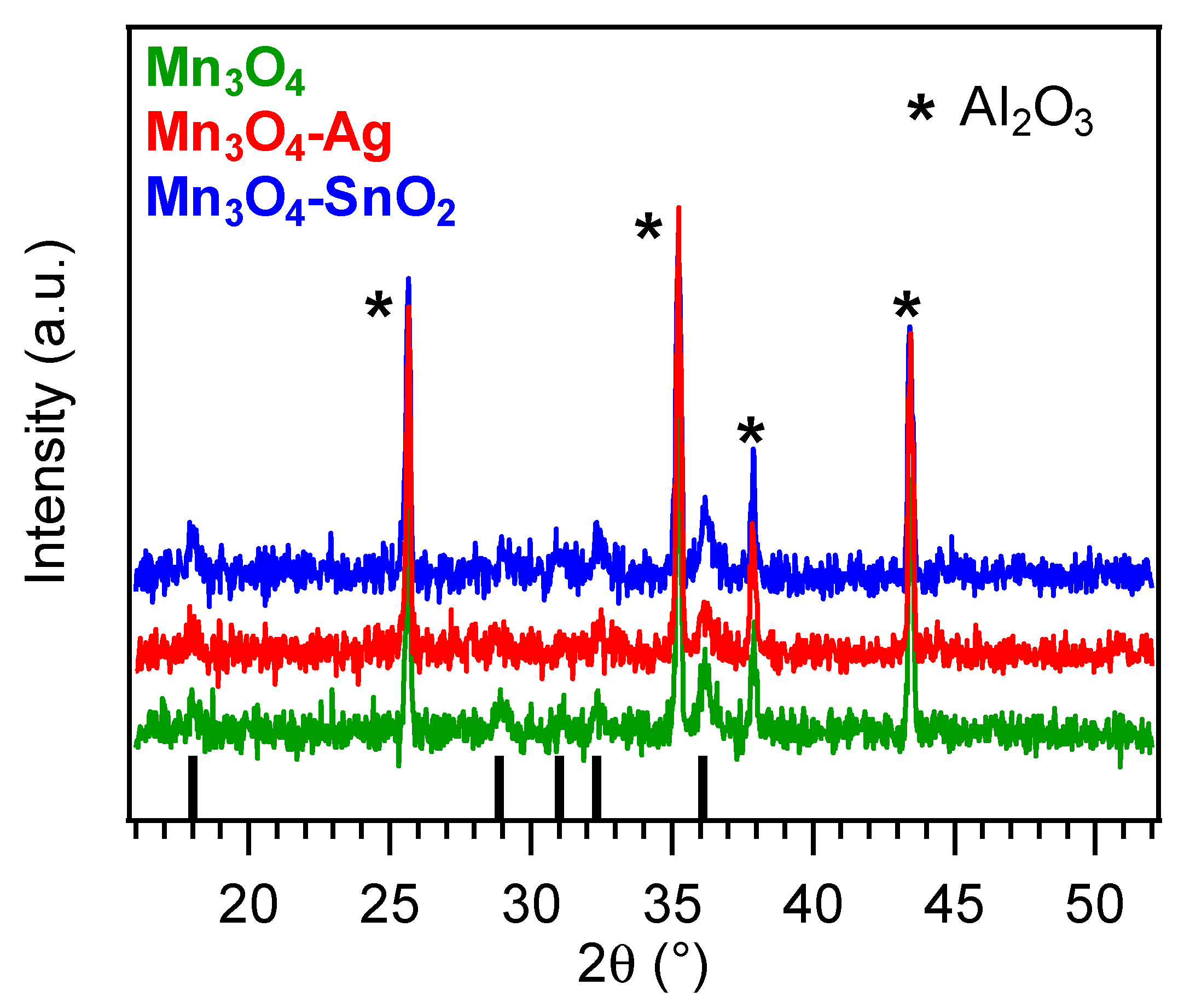

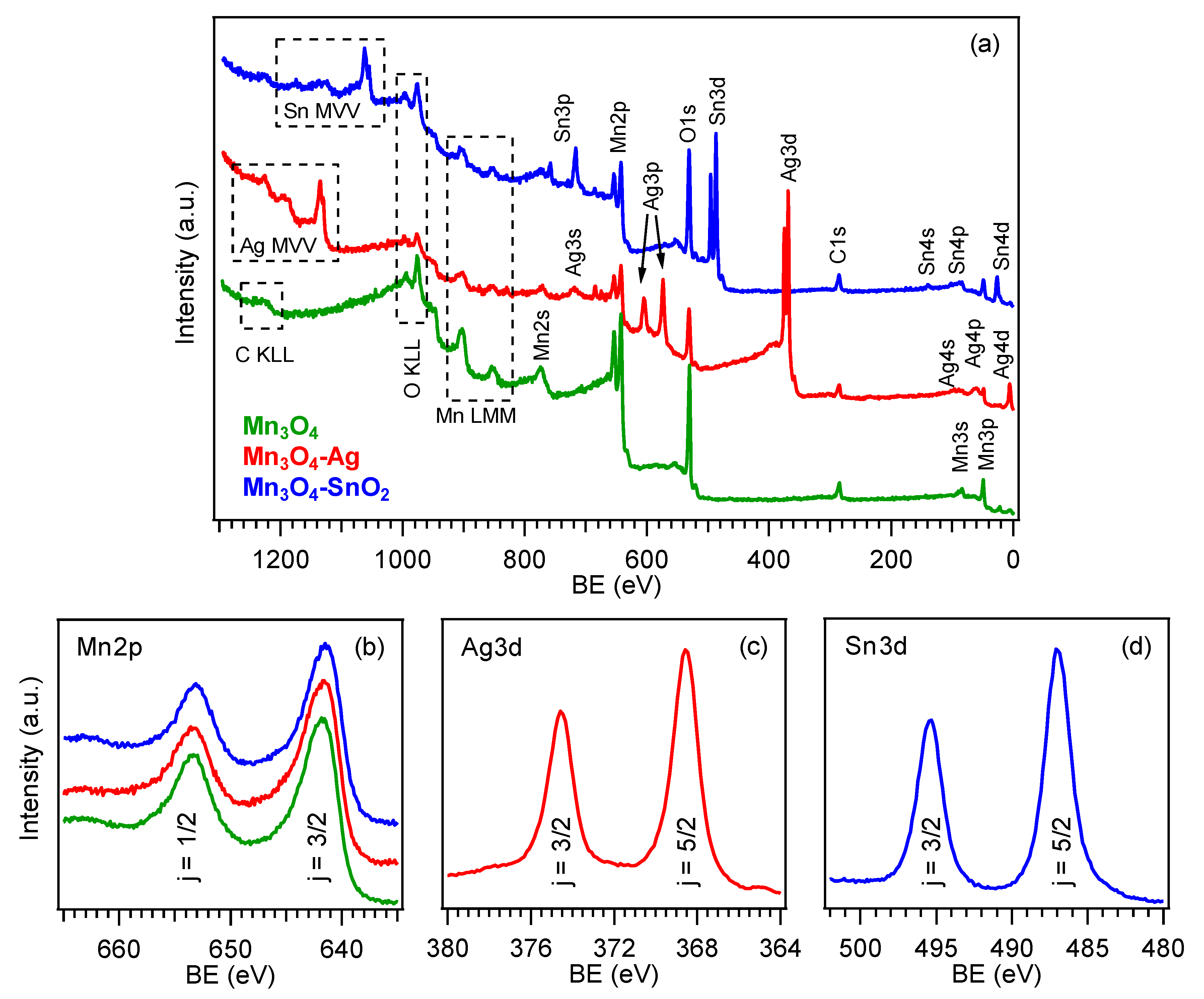

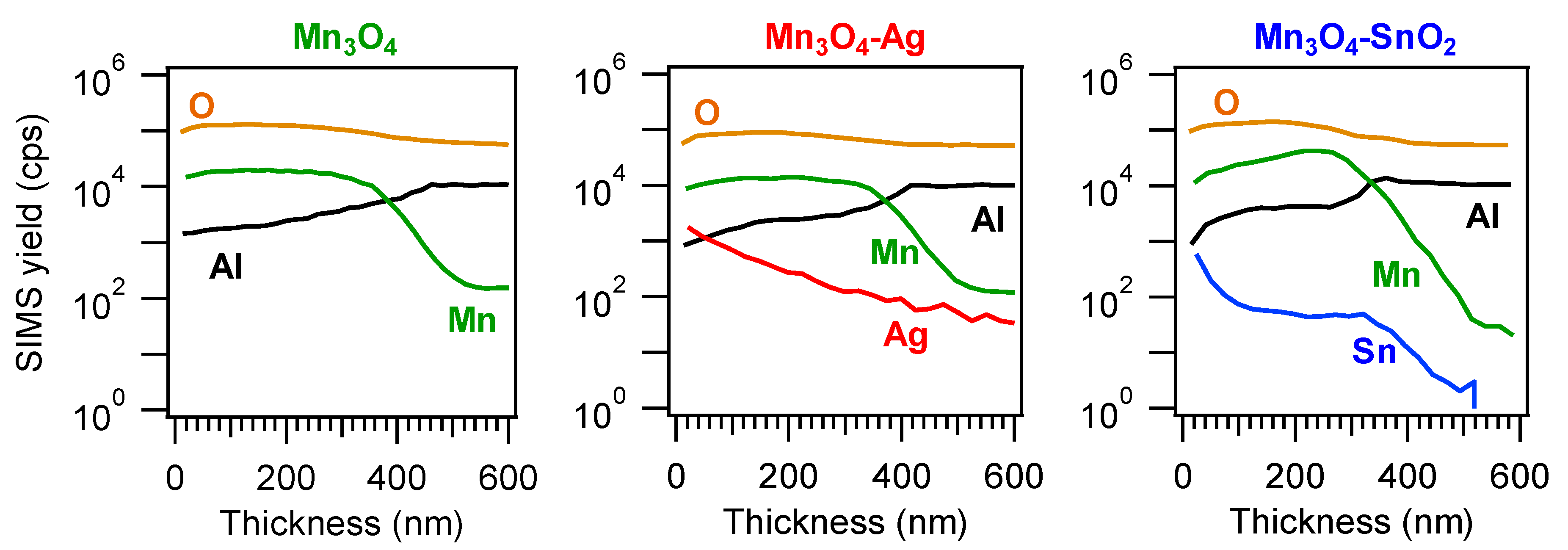

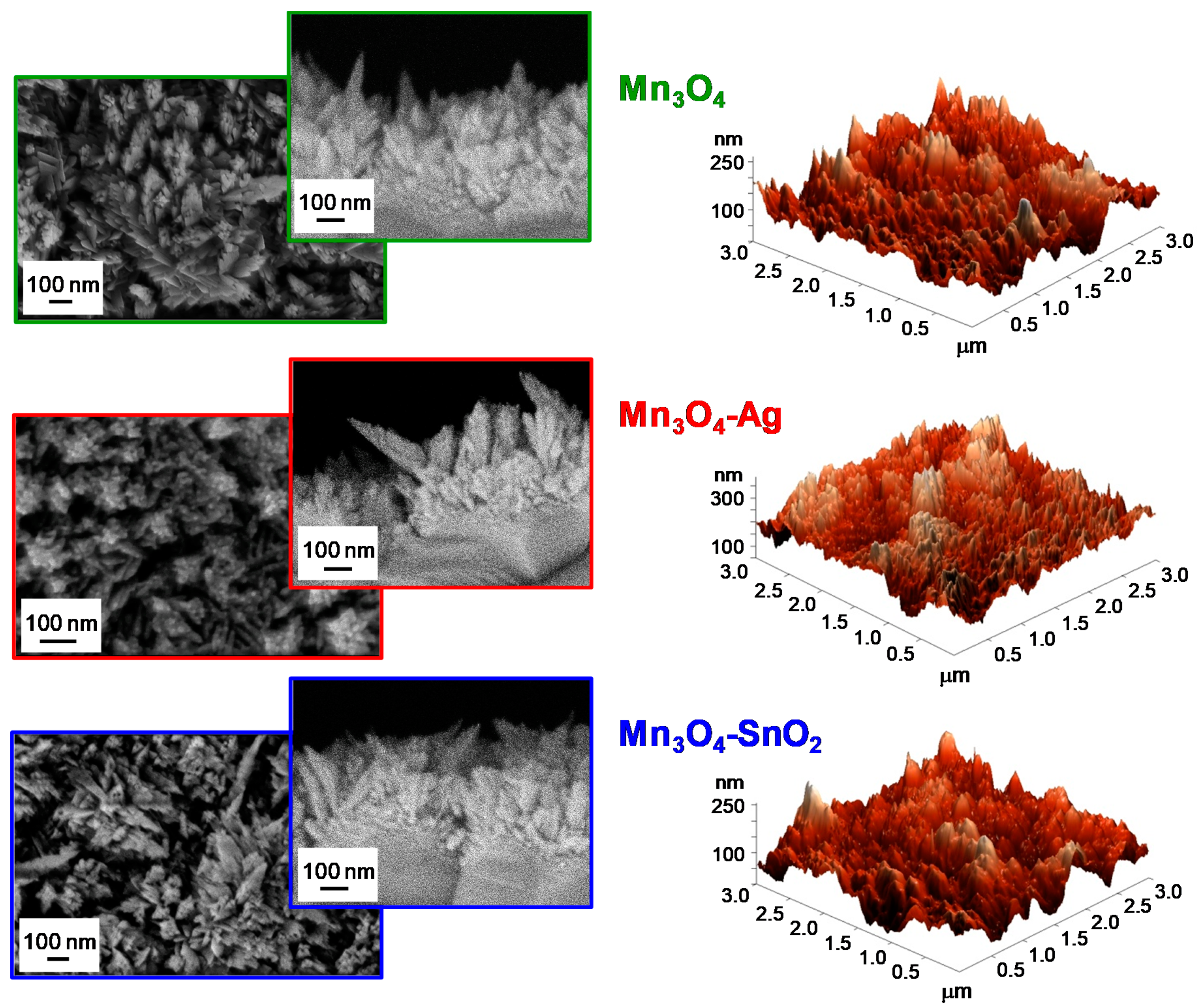

3.1. Chemico-Physical Characterization

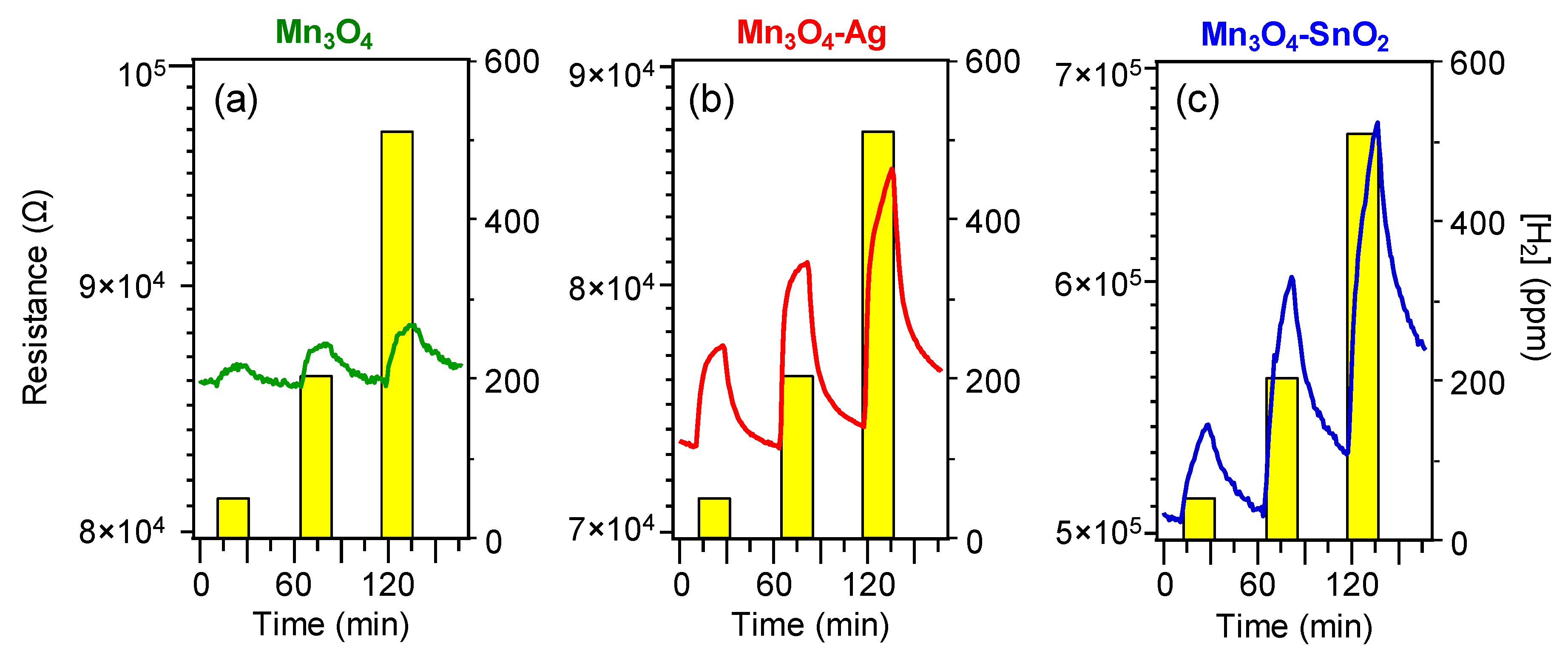

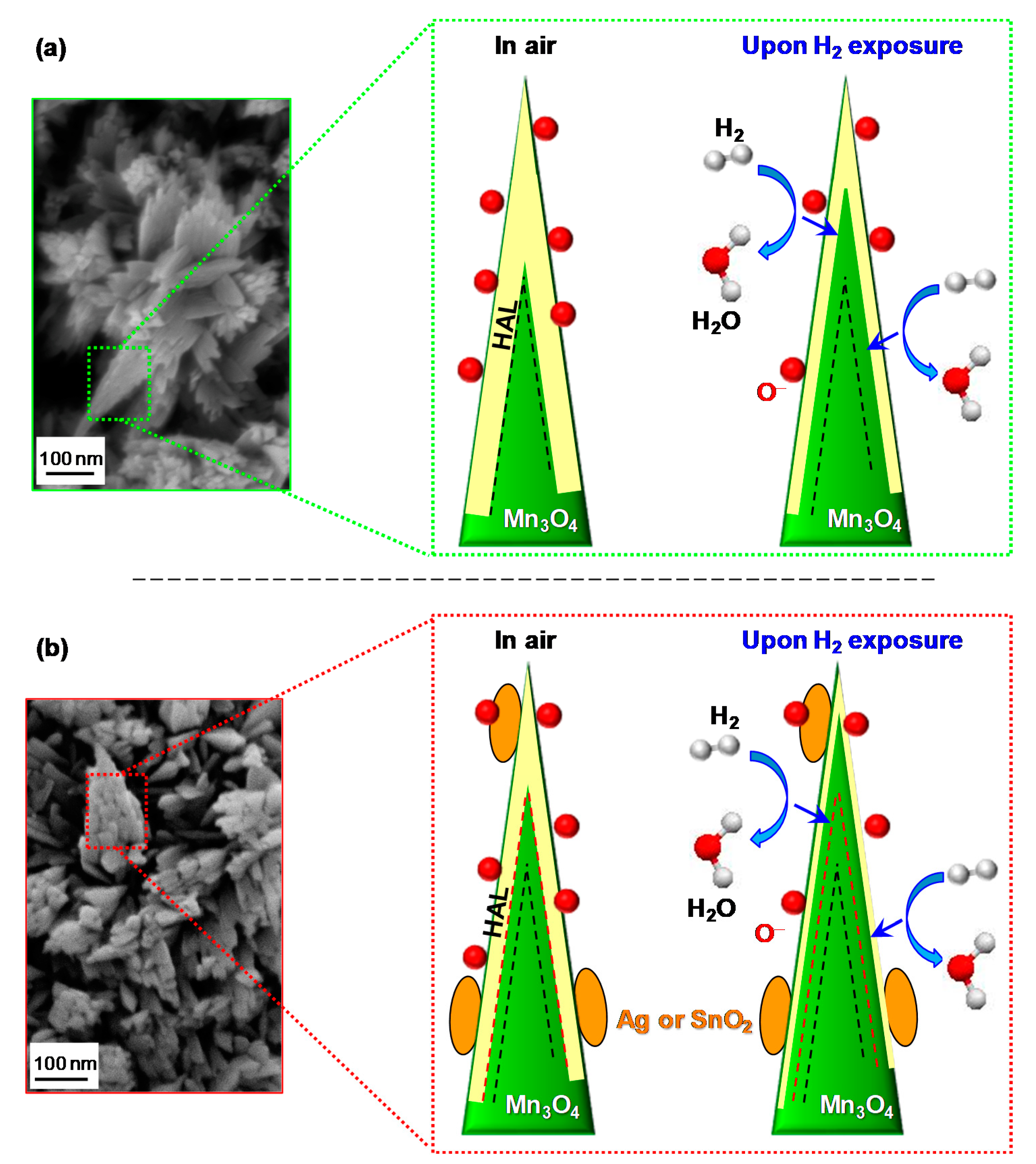

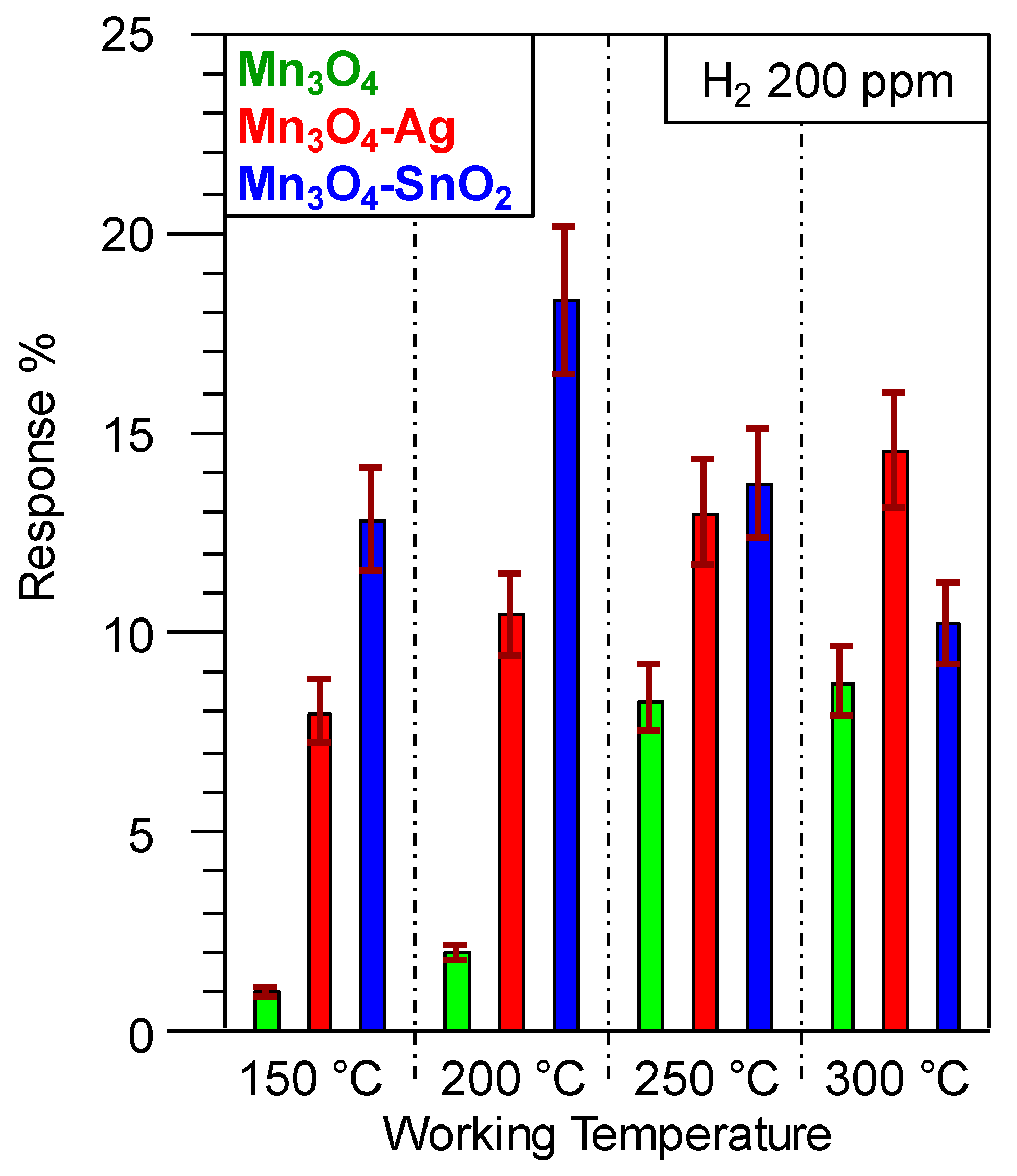

3.2. Gas Sensing Performances

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zöpfl, A.; Lemberger, M.-M.; König, M.; Ruhl, G.; Matysik, F.-M.; Hirsch, T. Reduced graphene oxide and graphene composite materials for improved gas sensing at low temperature. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 173, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamataki, M.; Tsamakis, D.; Brilis, N.; Fasaki, I.; Giannoudakos, A.; Kompitsas, M. Hydrogen gas sensors based on PLD grown NiO thin film structures. Phys. Status Solidi 2008, 205, 2064–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, L.D.; Le, D.T.T.; Duy, N.V.; Hoa, N.D.; Hieu, N.V. Single crystal cupric oxide nanowires: Length- and density-controlled growth and gas-sensing characteristics. Physica E 2014, 58, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıca, N.; Alev, O.; Arslan, L.Ç.; Öztürk, Z.Z. Characterization and gas sensing performances of noble metals decorated CuO nanorods. Thin Solid Film. 2019, 685, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonezzer, M.; Le, D.T.T.; Iannotta, S.; Hieu, N.V. Selective discrimination of hazardous gases using one single metal oxide resistive sensor. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 277, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.H.; Xiao, J.; Yang, G.W. Amorphization of cobalt monoxide nanocrystals and related explosive gas sensing applications. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 415501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, A.; Majumder, S.B.; Dewan, M.; Roy Chaudhuri, A. Hydrogen sensing characteristics of perovskite based calcium doped BiFeO3 thin films. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 18648–18656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Chandra, R. Highly sensitive and selective hydrogen gas sensor using sputtered grown Pd decorated MnO2 nanowalls. Sens. Actuators B 2016, 234, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Comini, E.; Zappa, D.; Poli, N.; Sberveglieri, G. Nickel oxide nanowires: Vapor liquid solid synthesis and integration into a gas sensing device. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 205701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, L.; Gui, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, C.; Chen, W. Synthesis and characterization of highly sensitive hydrogen (H2) sensing device based on Ag doped SnO2 nanospheres. Materials 2018, 11, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.Q.; Yang, L.; Qing, X.X.; Yu, K.; Wang, X.F. Trace level detection of hydrogen gas using birnessite-type manganese oxide. Sens. Actuators B 2015, 207, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.T.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Joe, J.H.; Lee, W. Hydrogen gas sensing properties of PdO thin films with nano-sized cracks. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 165503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Gong, H.; Chow, C.L.; Guo, J.; White, T.J.; Tse, M.S.; Tan, O.K. Low-temperature growth of SnO2 nanorod arrays and tunable n–p–n sensing response of a ZnO/SnO2 heterojunction for exclusive hydrogen sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 2680–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiani, L.; Zappa, D.; Maccato, C.; Comini, E.; Barreca, D.; Gasparotto, A. Quasi-1D MnO2 nanocomposites as gas sensors for hazardous chemicals. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 512, 145667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Bekermann, D.; Comini, E.; Devi, A.; Fischer, R.A.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Sberveglieri, G.; Tondello, E. 1D ZnO nano-assemblies by plasma-CVD as chemical sensors for flammable and toxic gases. Sens. Actuators B 2010, 149, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindhan, M.; Sidhureddy, B.; Chen, A. High-temperature hydrogen gas sensor based on three-dimensional hierarchical-nanostructured nickel–cobalt oxide. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 6005–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Hong, S.-H.; Hong, K.S. H2 and C2H5OH sensing characteristics of mesoporous p-type CuO films prepared via a novel precursor-based ink solution route. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 178, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviar, S.; Čapek, J.; Batková, Š.; Kumar, N.; Dvořák, F.; Duchoň, T.; Fialová, M.; Zeman, P. Hydrogen gas sensing properties of WO3 sputter-deposited thin films enhanced by on-top deposited CuO nanoclusters. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 22756–22764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Comini, E.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Pozza, A.; Sada, C.; Sberveglieri, G.; Tondello, E. Vapor phase synthesis, characterization and gas sensing performances of Co3O4 and Au/Co3O4 nanosystems. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 8054–8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, E.; Malik, A.; Martins, R. Photochemical sensors based on amorphous silicon thin films. Sens. Actuators B 1998, 46, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashtroudi, H.; Atkin, P.; Mackinnon, I.D.R.; Shafiei, M. Low-operating temperature resistive nanostructured hydrogen sensors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 26646–26664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübert, T.; Boon-Brett, L.; Black, G.; Banach, U. Hydrogen sensors—A review. Sens. Actuators B 2011, 157, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, R.M. A nose for hydrogen gas: Fast, sensitive H2 sensors using electrodeposited nanomaterials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; He, Z. The enhanced H2 selectivity of SnO2 gas sensors with the deposited SiO2 filters on surface of the sensors. Sensors 2019, 19, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comini, E.; Baratto, C.; Concina, I.; Faglia, G.; Falasconi, M.; Ferroni, M.; Galstyan, V.; Gobbi, E.; Ponzoni, A.; Vomiero, A.; et al. Metal oxide nanoscience and nanotechnology for chemical sensors. Sens. Actuators B 2013, 179, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappa, D.; Galstyan, V.; Kaur, N.; Munasinghe Arachchige, H.M.M.; Sisman, O.; Comini, E. “Metal oxide -based heterostructures for gas sensors”—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1039, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yi, G.; Li, H.; Shi, C.; Sun, G.; Zhang, Z. Hydrothermal synthesis of Co3O4/ZnO hybrid nanoparticles for triethylamine detection. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, M.; Fontcuberta, J.; Althammer, M.; Bibes, M.; Boschker, H.; Calleja, A.; Cheng, G.; Cuoco, M.; Dittmann, R.; Dkhil, B.; et al. Towards oxide electronics: A roadmap. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 482, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, N.D.; An, S.Y.; Dung, N.Q.; Van Quy, N.; Kim, D. Synthesis of p-type semiconducting cupric oxide thin films and their application to hydrogen detection. Sens. Actuators B 2010, 146, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Wei, D.; Fang, P.; Shen, Y. Highly selective NO2 sensor based on p-type nanocrystalline NiO thin films prepared by sol–gel dip coating. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiani, L.; Maccato, C.; Carraro, G.; Gasparotto, A.; Sada, C.; Comini, E.; Barreca, D. Tailoring vapor-phase fabrication of Mn3O4 nanosystems: From synthesis to gas-sensing applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 2962–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.-H. Highly sensitive and selective gas sensors using p-type oxide semiconductors: Overview. Sens. Actuators B 2014, 192, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Mirzaei, A.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S.S. SnO2 (n)-NiO (p) composite nanowebs: Gas sensing properties and sensing mechanisms. Sens. Actuators B 2018, 258, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jiao, Z.; Pan, D.; Li, Z.; Wu, M.; Shek, C.-H.; Wu, C.M.L.; Lai, J.K.L. Recent advances in manganese oxide nanocrystals: Fabrication, characterization, and microstructure. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3833–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, C.W.; Park, S.-Y.; Chung, J.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Transformation of ZnO nanobelts into single-crystalline Mn3O4 nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 6565–6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, N.; Thomas, P.; Divya, K.V.; Abraham, K.E. Enhanced room temperature gas sensing of aligned Mn3O4 nanorod assemblies functionalized by aluminum anodic membranes. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 335503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, T. Constructing hierarchical heterostructured Mn3O4/Zn2SnO4 materials for efficient gas sensing reaction. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1800115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiani, L.; Zappa, D.; Barreca, D.; Gasparotto, A.; Sada, C.; Tabacchi, G.; Fois, E.; Comini, E.; Maccato, C. Sensing nitrogen mustard gas simulant at the ppb scale via selective dual-site activation at Au/Mn3O4 interfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 23692–23700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccato, C.; Bigiani, L.; Carraro, G.; Gasparotto, A.; Sada, C.; Comini, E.; Barreca, D. Toward the detection of poisonous chemicals and warfare agents by functional Mn3O4 nanosystems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 12305–12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Said, L.; Inoubli, A.; Bouricha, B.; Amlouk, M. High Zr doping effects on the microstructural and optical properties of Mn3O4 thin films along with ethanol sensing. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2017, 171, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigiani, L.; Zappa, D.; Maccato, C.; Gasparotto, A.; Sada, C.; Comini, E.; Barreca, D. Mn3O4 nanomaterials functionalized with Fe2O3 and ZnO: Fabrication, characterization, and ammonia sensing properties. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1901239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.W.; Kwon, Y.J.; Na, H.G.; Cho, H.Y.; Lee, C.; Jung, J.H. One-pot synthesis of Mn3O4-decorated GaN nanowires for drastic changes in magnetic and gas-sensing properties. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 139, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakate, U.T.; Ahmad, R.; Patil, P.; Wang, Y.; Bhat, K.S.; Mahmoudi, T.; Yu, Y.T.; Suh, E.-K.; Hahn, Y.-B. Improved selectivity and low concentration hydrogen gas sensor application of Pd sensitized heterojunction n-ZnO/p-NiO nanostructures. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 797, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Carraro, G.; Comini, E.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Sada, C.; Sberveglieri, G.; Tondello, E. Novel synthesis and gas sensing performances of CuO–TiO2 nanocomposites functionalized with Au nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 10510–10517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, S.S.; Ghosh, S.; Sharma, S.K.; Bal, R. Fabrication of Ag nanoparticles supported on one-dimensional (1D) Mn3O4 spinel nanorods for selective oxidation of cyclohexane at room temperature. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 3812–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, G.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Gombac, V.; Rossi, F.; Montini, T.; Peeters, D.; Bontempi, E.; Sada, C.; Barreca, D.; et al. Solar H2 generation via ethanol photoreforming on ε-Fe2O3 nanorod arrays activated by Ag and Au nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 32174–32179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, H.; Kundu, S.; Ghosh, S.K. Size-selective silver-induced evolution of Mn3O4-Ag nanocomposites for effective ethanol sensing. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 6991–6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Q.; Barreca, D.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Tondello, E.; Sada, C.; Comini, E.; Devi, A.; Fischer, R.A. Ag/ZnO nanomaterials as high performance sensors for flammable and toxic gases. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 025502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, G.; Barreca, D.; Comini, E.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C.; Sada, C.; Sberveglieri, G. Controlled synthesis and properties of β-Fe2O3 nanosystems functionalized with Ag or Pt nanoparticles. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 6469–6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Alam, M.M.; Asiri, A.M. Fabrication of an acetone sensor based on facile ternary MnO2/Gd2O3/SnO2 nanosheets for environmental safety. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 9938–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, D.; Carraro, G.; Fois, E.; Gasparotto, A.; Gri, F.; Seraglia, R.; Wilken, M.; Venzo, A.; Devi, A.; Tabacchi, G.; et al. Manganese(II) molecular sources for plasma-assisted CVD of Mn oxides and fluorides: From precursors to growth process. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccato, C.; Bigiani, L.; Carraro, G.; Gasparotto, A.; Seraglia, R.; Kim, J.; Devi, A.; Tabacchi, G.; Fois, E.; Pace, G.; et al. Molecular engineering of MnII diamine diketonate precursors for the vapor deposition of manganese oxide nanostructures. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17954–17963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreca, D.; Gasparotto, A.; Tondello, E.; Sada, C.; Polizzi, S.; Benedetti, A. Nucleation and growth of nanophasic CeO2 thin films by plasma-enhanced CVD. Chem. Vap. Depos. 2003, 9, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattelaer, F.; Bosserez, T.; Ronge, J.; Martens, J.A.; Dendooven, J.; Detavernier, C. Manganese oxide films with controlled oxidation state for water splitting devices through a combination of atomic layer deposition and post-deposition annealing. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 98337–98343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Hu, K.; Zhang, B.; He, L.; Zhou, Q. Superior hydrogen sensing property of porous NiO/SnO2 nanofibers synthesized via carbonization. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, D.; Seah, M.P. Practical Surface Analysis: Auger and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://xpspeak.software.informer.com/4.1/ (accessed on 31 December 2019).

- Available online: http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- JCPDS card no. 024-0734 (2000).

- Bigiani, L.; Barreca, D.; Gasparotto, A.; Maccato, C. Mn3O4 thin films functionalized with Ag, Au, and TiO2 analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2018, 25, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database. Available online: http://srdata.nist.gov/xps (accessed on 31 December 2019).

- Sharma, J.K.; Srivastava, P.; Ameen, S.; Akhtar, M.S.; Singh, G.; Yadava, S. Azadirachta Indica plant-assisted green synthesis of Mn3O4 nanoparticles: Excellent thermal catalytic performance and chemical sensing behavior. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 472, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yates, J.T. Band bending in semiconductors: Chemical and physical consequences at surfaces and interfaces. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5520–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Boudiba, A.; Navio, C.; Olivier, M.-G.; Snyders, R.; Debliquy, M. Study of selectivity of NO2 sensors composed of WO3 and MnO2 thin films grown by radio frequency sputtering. Sens. Actuators B 2012, 161, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Yoon, Y.; Lee, G.S. Hydrogen sensing characteristics of carbon-nanotube sheet decorated with manganese oxides. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 577, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuel Cell-Based System Converts Atmospheric CO2 into Usable Electric Current. Available online: https://www.theengineer.co.uk/fuel-cell-based-system-co2/ (accessed on 31 December 2019).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bigiani, L.; Zappa, D.; Maccato, C.; Gasparotto, A.; Sada, C.; Comini, E.; Barreca, D. Hydrogen Gas Sensing Performances of p-Type Mn3O4 Nanosystems: The Role of Built-in Mn3O4/Ag and Mn3O4/SnO2 Junctions. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030511

Bigiani L, Zappa D, Maccato C, Gasparotto A, Sada C, Comini E, Barreca D. Hydrogen Gas Sensing Performances of p-Type Mn3O4 Nanosystems: The Role of Built-in Mn3O4/Ag and Mn3O4/SnO2 Junctions. Nanomaterials. 2020; 10(3):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030511

Chicago/Turabian StyleBigiani, Lorenzo, Dario Zappa, Chiara Maccato, Alberto Gasparotto, Cinzia Sada, Elisabetta Comini, and Davide Barreca. 2020. "Hydrogen Gas Sensing Performances of p-Type Mn3O4 Nanosystems: The Role of Built-in Mn3O4/Ag and Mn3O4/SnO2 Junctions" Nanomaterials 10, no. 3: 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030511

APA StyleBigiani, L., Zappa, D., Maccato, C., Gasparotto, A., Sada, C., Comini, E., & Barreca, D. (2020). Hydrogen Gas Sensing Performances of p-Type Mn3O4 Nanosystems: The Role of Built-in Mn3O4/Ag and Mn3O4/SnO2 Junctions. Nanomaterials, 10(3), 511. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030511