Antimicrobial Efficacy and Soft-Tissue Safety of Air-Polishing Powders in Periodontal Therapy: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Overview of Air-Polishing Powders

3.1. Characteristics and Properties

3.2. Side Effects

4. Air-Polishing Powders: Mechanisms of Action in Biofilm Removal

4.1. Mechanical Disruption

| Air-Polishing Powders | Composition | Particle Size (µm) | Particle Shape | Solubility | Abrasiveness | Clinical Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) [14,47] | Sodium bicarbonate (non-toxic) | 1–250 (mean particle size 40–65) | Angular, chiseled, sharp edges | Water-soluble | High-abrasive | Supragingival biofilm and early calculus removal |

| Glycine [14,47] | Amino acid (non-toxic, organic salt crystals) | 25–65 (mean particle size 25) | Less angular, round edges | Slow water-solubility | Low-abrasive (~80% less than NaHCO3) | Supra- and subgingival biofilm removal; use on teeth, implants, soft tissue and orthodontic appliance |

| Erythritol [14,47] | Sugar alcohol, polyol (non-toxic, chemically neutral) | 14–31 (mean particle size 14) | Fine and extra-fine rounded particles | Water-soluble | Minimally abrasive | Supra- and subgingival biofilm and young calculus removal; prophylaxis treatments (gingivitis, periodontitis); primary and secondary supportive periodontal therapy; non-surgical treatment of peri-implantitis and mucositis, implant maintenance; fixed orthodontic appliance; tongue and soft tissue cleaning |

| Trehalose [34,48] | Disaccharide (non-toxic) | 30 and 65 | Fine particles | Water-soluble | Low-abrasive | Supragingival cleaning and subgingival biofilm removal; extrinsic discoloration removal; use in supportive periodontal therapy |

| Tagatose [35,49,50] | Non-cariogenic sugar | 15 | Fine particles | Water-soluble | Low-abrasive | Supra- and subgingival cleaning |

| Bioactive glass [16,37] | Glass-based bioactive particles (silica-based, bioactive, non-toxic) | 1–10 | Regular uniform shape | Low-water-soluble | Low-abrasive | Supra- and subgingival biofilm removal; remineralization of dental tissue |

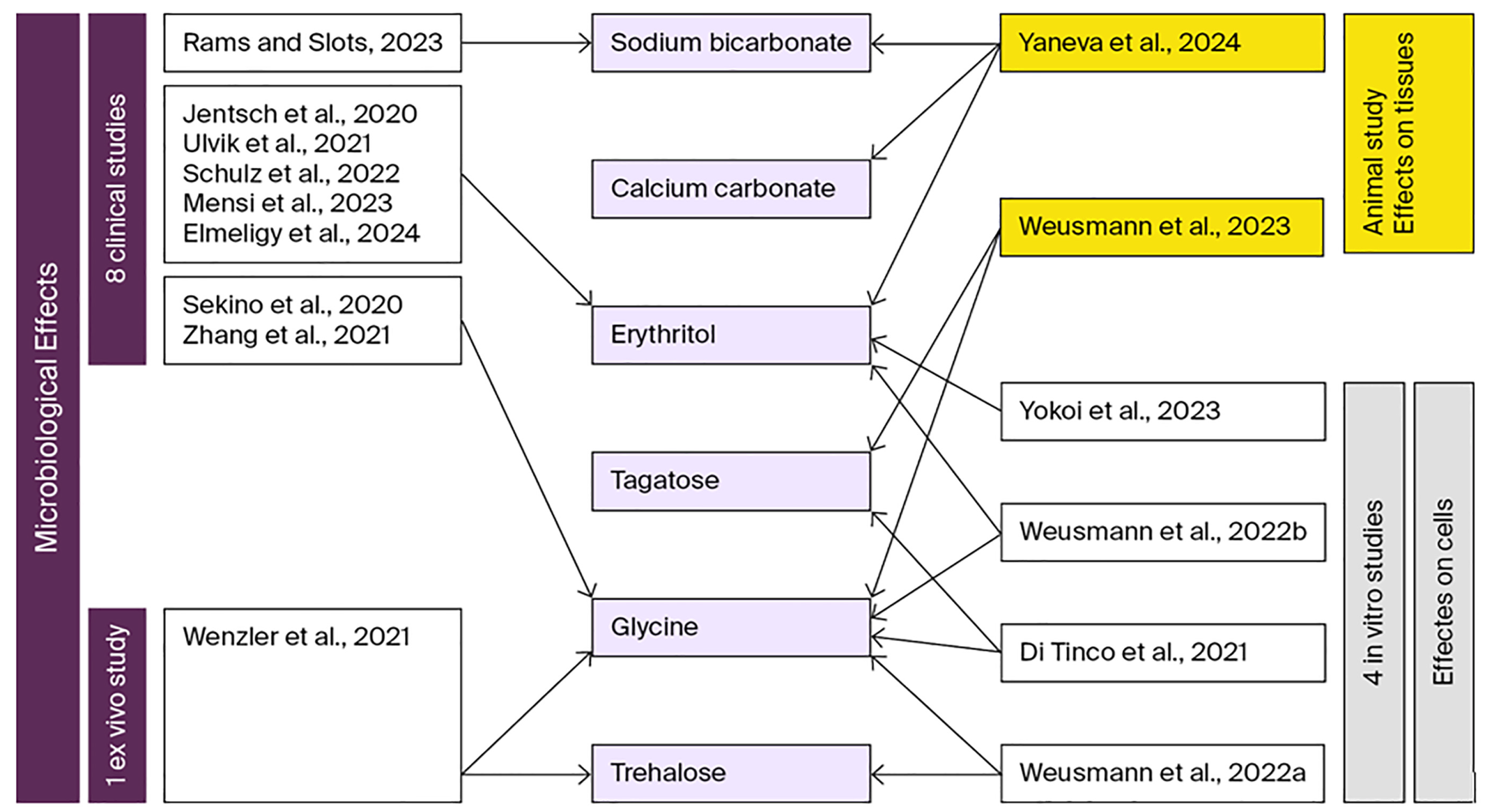

4.2. Microbiological Findings

5. Effects of Air-Polishing Powders on Human Cell Response

5.1. Gingival Fibroblasts

5.2. Dental Pulp Stem Cells

6. Impact of Air-Polishing Powders on Local Tissues: Histological Observations from Experimental Models

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cadosch, J.; Zimmermann, U.; Ruppert, M.; Guindy, J.; Case, D.; Zappa, U. Root surface debridement and endotoxin removal. J. Periodontal Res. 2003, 38, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritz, L.; Hefti, A.F.; Rateitschak, K.H. An in vitro investigation on the loss of root substance in scaling with various instruments. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1991, 18, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculean, A.; Bastendorf, K.-D.; Becker, C.; Bush, B.; Einwag, J.; Lanoway, C.; Platzer, U.; Schmage, P.; Schoeneich, B.; Walter, C.; et al. A paradigm shift in mechanical biofilm management? Subgingival air polishing: A new way to improve mechanical biofilm management in the dental practice. Quintessence Int. 2013, 44, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulkareem, A.A.; Al-Taweel, F.B.; Al-Sharqi, A.J.; Gul, S.S.; Sha, A.; Chapple, I.L. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of periodontitis: From symbiosis to dysbiosis. J. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 15, 2197779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, X.; Luo, G.; Zhao, J.; Bai, G.; Xu, D. Innovative strategies targeting oral microbial dysbiosis: Unraveling mechanisms and advancing therapies for periodontitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1556688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Berglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M.S.; Consultants, T.E.W.P.A.M.; Lambert, N.L.F. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 4–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Ying, Y.; Yuan, J.; Chen, K.; Deng, S.; Wang, Q. Association of polymicrobial interactions with dental caries development and prevention. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1162380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Teughels, W.; on behalf of group A of the European Workshop on Periodontology. Innovations in non-surgical periodontal therapy: Consensus Report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundidpun, P.; Srisuwantha, R.; Laosrisin, N. Clinical effects of photodynamic therapy as an adjunct to full-mouth ultrasonic scaling and root planing in treatment of chronic periodontitis. Laser Ther. 2018, 27, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, J.; Corbet, E.F.; Jin, L. Combined photodynamic and low-level laser therapies as an adjunct to nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2010, 46, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micu, I.C.; Muntean, A.; Roman, A.; Stratul, Ș.I.; Pall, E.; Ciurea, A.; Soancă, A.; Negucioiu, M.; Tudoran, L.B.; Delean, A.G. A Local Desiccant Antimicrobial Agent as an Alternative to Adjunctive Antibiotics in the Treatment of Periodontitis: A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: Risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2014, 5, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, G.; Sun, J.; Dong, S.; Ding, J. Advanced biomaterials for targeting mature biofilms in periodontitis therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 48, 474–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, D.; Natoli, V.; Srivastava, K.C.; A Alzoubi, I.; Nagy, A.I.; Hamza, M.O.; Al-Johani, K.; Alam, M.K.; Khurshid, Z. Novel Approach to Dental Biofilm Management through Guided Biofilm Therapy (GBT): A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weusmann, J.; Deschner, J.; Imber, J.-C.; Damanaki, A.; Leguizamón, N.D.P.; Nogueira, A.V.B. Cellular effects of glycine and trehalose air-polishing powders on human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 26, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K, J.; Rg, H.; D, G. Air-Polishing in Subgingival Root Debridement during Supportive Periodontal Care: A Review. J. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzler, J.-S.; Krause, F.; Böcher, S.; Falk, W.; Birkenmaier, A.; Conrads, G.; Braun, A. Antimicrobial Impact of Different Air-Polishing Powders in a Subgingival Biofilm Model. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersilka, G.; Faggion, C.M.; Stratmann, U.; Gerss, J.; Ehmke, B.; Haeberlein, I.; Flemmig, T.F. Effect of glycine powder air-polishing on the gingiva. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, L.; Del Fabbro, M.; Bortolin, M.; Vassena, C.; De Vecchi, E.; Taschieri, S. Biofilm Removal and Antimicrobial Activity of Two Different Air-Polishing Powders: An In Vitro Study. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, e363–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägi, T.; Hofmänner, P.; Eick, S.; Donnet, M.; Salvi, G.E.; Sculean, A.; Ramseier, C.A. The effects of erythritol air-polishing powder on microbiologic and clinical outcomes during supportive periodontal therapy: Six-month results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Quintessence Int. 2015, 46, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeligy, S.M.A.; Saleh, W.; Elewa, G.M.; Abu El-Ezz, H.Z.; Mahmoud, N.M.; Elmeadawy, S. The efficacy of diode laser and subgingival air polishing with erythritol in treatment of periodontitis (clinical and microbiological study). BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laleman, I.; Cortellini, S.; De Winter, S.; Herrero, E.R.; DeKeyser, C.; Quirynen, M.; Teughels, W. Subgingival debridement: End point, methods and how often? Periodontology 2000 2017, 75, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, G.G.; Leite, F.R.M.; Pennisi, P.R.C.; López, R.; Paranhos, L.R. Use of air polishing for supra- and subgingival biofilm removal for treatment of residual periodontal pockets and supportive periodontal care: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, B.; Shentov, P.; Bogoev, D.; Mutafchieva, M.; Atanasova-Vladimirova, S.; Dimitrov, K.; Vladova, D. Gingival Margin Damage During Supragingival Dental Polishing by Inexperienced Operator—Pilot Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersilka, G.J. Subgingival air-polishing in the treatment of periodontal biofilm infections. Periodontology 2000 2010, 55, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V.A.; Neha; S, A. Air Polishing-An Overview. Sch. J. Dent. Sci. 2018, 5, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, D.A.; Hill, R.G.; Gillam, D.G. Air-Polishing in Subgingival Root Debridement: A Critical Literature Review. J. Dent. Oral Biol. 2017, 2, 1065. [Google Scholar]

- Pratten, J.; Wiecek, J.; Mordan, N.; Lomax, A.; Patel, N.; Spratt, D.; Middleton, A.M. Physical disruption of oral biofilms by sodium bicarbonate: Anin vitrostudy. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2016, 14, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, A. A comparison of Listerine® and sodium bicarbonate oral cleansing solutions on dental plaque colonisation and incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients: A randomised control trial. Intensiv. Crit. Care Nurs. 2013, 29, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, C.M.; Daubert, D.M.; Davis, K.; Deming, J.; Flemmig, T.F.; Pattison, A.; Roulet, J.-F.; Stambaugh, R.V. Consensus Conference Findings on Supragingival and Subgingival Air Polishing. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2017, 38, e1–e4. [Google Scholar]

- Weusmann, J.; Deschner, J.; Imber, J.-C.; Damanaki, A.; Cerri, P.S.; Leguizamón, N.; Beisel-Memmert, S.; Nogueira, A.V.B. Impact of glycine and erythritol/chlorhexidine air-polishing powders on human gingival fibroblasts: An in vitro study. Ann. Anat. - Anat. Anz. 2022, 243, 151949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-J.; Kwon, E.-Y.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Choi, J.; Joo, J.-Y. Clinical and microbiological effects of the supplementary use of an erythritol powder air-polishing device in non-surgical periodontal therapy: A randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2018, 48, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkstein, S.; Reiff, R.L.; McKinney, J.F.; Killoy, W.J. Supragingival Root Surface Removal during Maintenance Procedures Utilizing an Air-Powder Abrasive System or Hand Scaling. J. Periodontol. 1987, 58, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse, A.B.; Akakpo, D.L.; Maamar, R.; Woelber, J.P.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Vach, K.; Ratka-Krueger, P. Trehalose powder for subgingival air-polishing during periodontal maintenance therapy: A randomized controlled trial. J. Periodontol. 2018, 90, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Tinco, R.; Bertani, G.; Pisciotta, A.; Bertoni, L.; Bertacchini, J.; Colombari, B.; Conserva, E.; Blasi, E.; Consolo, U.; Carnevale, G. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Effect of Air-Polishing Treatments and Their Influence on Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Seeded on Titanium Disks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasibul, K.; Nakayama-Imaohji, H.; Hashimoto, M.; Yamasaki, H.; Ogawa, T.; Waki, J.; Tada, A.; Yoneda, S.; Tokuda, M.; Miyake, M.; et al. D-Tagatose inhibits the growth and biofilm formation of Streptococcus�mutans. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 17, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janicki, T.; Sobczak-Kupiec, A.; Skomro, P.; Wzorek, Z. Surface of root cementum following air-polishing with bioactive hydroxyapatite (Ca and P mapping). A pilot study. Acta Bioeng Biomech 2012, 14, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Petersilka, G.J.; Bell, M.; Mehl, A.; Hickel, R.; Flemmig, T.F. Root defects following air polishing. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louropoulou, A.; Slot, D.E.; Van der Weijden, F.A. Titanium surface alterations following the use of different mechanical instruments: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 23, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F.; Ferrari, D.; Popovski, K.; Hartig, B.; Becker, J. Influence of different air-abrasive powders on cell viability at biologically contaminated titanium dental implants surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 88B, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, G.; Becker, J.; Schwarz, F. Effectivity of air-abrasive powder based on glycine and tricalcium phosphate in removal of initial biofilm on titanium and zirconium oxide surfaces in an ex vivo model. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 20, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sygkounas, E.; Louropoulou, A.; Schoenmaker, T.; de Vries, T.J.; Van der Weijden, F.A. Influence of various air-abrasive powders on the viability and density of periodontal cells: An in vitro study. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2017, 106, 1955–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemmig, T.F.; Arushanov, D.; Daubert, D.; Rothen, M.; Mueller, G.; Leroux, B.G. Randomized Controlled Trial Assessing Efficacy and Safety of Glycine Powder Air Polishing in Moderate-to-Deep Periodontal Pockets. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemmig, T.F.; Hetzel, M.; Topoll, H.; Gerss, J.; Haeberlein, I.; Petersilka, G. Subgingival Debridement Efficacy of Glycine Powder Air Polishing. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, Y.C.; Corbet, E.F.; Jin, L.J. Subgingival glycine powder air-polishing as an additional approach to nonsurgical periodontal therapy in subjects with untreated chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2018, 53, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, A.A.; Hill, R.G.; Fleming, P.S.; Patel, M.P. Development of a novel bioactive glass for air-abrasion to selectively remove orthodontic adhesives. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 22, 1839–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMS Electro Medical Systems. AIRFLOW® PLUS Powder – Technical Product Information. EMS Dental, Nyon, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.ems-dental.com/en/products/new-airflow-plus-powder-now-aluminum-bottle (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- DÜRR Dental SE. Lunos® Prophy Powder Gentle Clean and Perio Combi – Technical Data Sheet. DÜRR Dental SE, Bietigheim-Bissingen, Germany, 2023. Available online: https://www.duerrdental.com/en/products/dental-care/consumables/lunosr-prophy-powder/ (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- smartdent GmbH. smartPearls Plus Prophylaxis Powder (Tagatose-Based)—Product Specification; smartdent GmbH: Rodgau, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Weusmann, J.; Deschner, J.; Keppler, C.; Imber, J.-C.; Ziskoven, P.C.; Schumann, S. The working angle in low-abrasive air polishing has an influence on gingival damage—an ex vivo porcine model. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 6199–6207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, M.A.; Begum, P.S.; Viswanath, B.; Rajagopal, S. Multifarious Beneficial Effect of Nonessential Amino Acid, Glycine: A Review. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1716701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Wheeler, M.D.; Li, X.; Froh, M.; Schemmer, P.; Yin, M.; Bunzendaul, H.; Bradford, B.; Lemasters, J.J. L-Glycine: A novel antiinflammatory, immunomodulatory, and cytoprotective agent. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2003, 6, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Cerón, K.A.; Sánchez-Muñoz, F.; Gutierrez-Rojas, R.A.; Acevedo-Villavicencio, L.N.; Flores-Zarate, A.V.; Huang, F.; Giacoman-Martinez, A.; Villafaña, S.; Romero-Nava, R. Glycine: The Smallest Anti-Inflammatory Micronutrient. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bergenhenegouwen, J.; Braber, S.; Loonstra, R.; Buurman, N.; Rutten, L.; Knipping, K.; Savelkoul, P.J.; Harthoorn, L.F.; Jahnsen, F.L.; Garssen, J.; et al. Oral exposure to the free amino acid glycine inhibits the acute allergic response in a model of cow’s milk allergy in mice. Nutr. Res. 2018, 58, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.; Scotti, E.; Sordillo, A.; Dalè, M.; Calza, S. Clinical evaluation of air polishing with erythritol powder followed by ultrasonic calculus removal versus conventional ultrasonic debridement and rubber cup polishing for the treatment of gingivitis: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 20, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, H.F.R.; Flechsig, C.; Kette, B.; Eick, S. Adjunctive air-polishing with erythritol in nonsurgical periodontal therapy: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekino, S.; Ogawa, T.; Murakashi, E.; Ito, H.; Numabe, Y. Clinical and microbiological effect of frequent subgingival air polishing on periodontal conditions: A split-mouth randomized controlled trial. Odontology 2020, 108, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Chu, C.; Jing, J.; Yao, N.; Sun, Q.; Li, S. Clinical, inflammatory and microbiological outcomes of full-mouth scaling with adjunctive glycine powder air-polishing: A randomized trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 48, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvik, I.M.; Sæthre, T.; Bunæs, D.F.; Lie, S.A.; Enersen, M.; Leknes, K.N. A 12-month randomized controlled trial evaluating erythritol air-polishing versus curette/ultrasonic debridement of mandibular furcations in supportive periodontal therapy. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.; Stein, J.M.; Schumacher, A.; Kupietz, D.; Yekta-Michael, S.S.; Schittenhelm, F.; Conrads, G.; Schaller, H.-G.; Reichert, S. Nonsurgical Periodontal Treatment Options and Their Impact on Subgingival Microbiota. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.; Caselli, E.; D’aCcolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Farina, R.; Scotti, E.; Guarnelli, M.E.; Fabbri, C.; Garzetti, G.; Marchetti, S.; et al. Efficacy of the additional use of subgingival air-polishing with erythritol powder in the treatment of periodontitis patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Part II: Effect on sub-gingival microbiome. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 27, 2547–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Rams, T.; Slots, J. Effect of supragingival air polishing on subgingival periodontitis microbiota. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2023, 57, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Shi, G. Smoking and microbiome in oral, airway, gut and some systemic diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, H.; Furukawa, M.; Wang, J.; Aoki, Y.; Raju, R.; Ikuyo, Y.; Yamada, M.; Shikama, Y.; Matsushita, K. Erythritol Can Inhibit the Expression of Senescence Molecules in Mouse Gingival Tissues and Human Gingival Fibroblasts. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe, D.N.; Bennardo, F.; Silaghi, M.; Popescu, D.-M.; Maftei, G.-A.; Bătăiosu, M.; Surlin, P. Subgingival Use of Air-Polishing Powders: Status of Knowledge: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Year) | Powder Used | Study Type/Sample | Key Microbial Outcomes | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jentsch et al., 2020 [56] | Erythritol + CHX | RCT, 42 periodontitis patients | Rare A. actinomycetemcomitans; P. gingivalis ↓ in control at 3 mo; T. forsythia & T. denticola ↓ at 6 mo in erythritol group; no intergroup difference | Multiplex real-time qPCR |

| Sekino et al., 2020 [57] | Glycine | RCT, 19 maintenance patients | ↓ P. gingivalis, T. forsythia trends up to 90 days; T. denticola non-significant reduction; no intergroup differences | Real-time PCR with hybridization |

| Zhang et al., 2020 [58] | Glycine | RCT, 41 stage II-IV periodontitis patients | ↓ P. gingivalis & A. actinomycetemcomitans at 24 h and 3 mo; F. nucleatum ↓ in glycine groups; P. gingivalis significantly reduced only when glycine before SRP at 6 wks | Real-time PCR |

| Ulvik et al., 2021 [59] | Erythritol + CHX | RCT, 20 maintenance patients with furcations | No intergroup differences; ↑ T. denticola & P. micra at 6 mo in both groups | Checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization |

| Wenzler et al. 2021 [17] | Glycine Trehalose | In vitro, Animal model | Total bacterial load ↓ 99% (glycine), ↓ 93.3% (trehalose), ↓ 77.6% (water); ↓ P. gingivalis, F. nucleatum, C. rectus, A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. intermedia | Real-time PCR |

| Schulz et al., 2022 [60] | Erythritol | RCT, 40 stage III-IV periodontitis patients | ↓ Fusobacterium and uncultured Prevotella post-treatment, recolonization by 6 mo | 16S rRNA sequencing, QIIME, alpha/beta diversity |

| Mensi et al., 2022 [61] | Erythritol + CHX | RCT, 40 stage III-IV periodontitis patients | ↓ T. denticola at 3 mo in test; reductions in A. israelii, F. alocis, P. endodontalis, T. forsythia, T. socranskii mainly in females and non-smokers | qPCR microarray (93 species) |

| Rams & Slots, 2023 [62] | Sodium bicarbonate | CCT, 15 stage III periodontitis patients | 84.9% ↓ total viable counts; ↓ Prevotella intermedia/nigrescens, F. nucleatum, red/orange complex species; motile morphotypes ↓ by 85.3% | Microbial culture, and phase-contrast microscopy |

| Elmeligy et al., 2024 [21] | Erythritol | RCT, 24 stage I-II periodontitis patients | Immediate ↑ A. actinomycetemcomitans; ↓ P. gingivalis post-treatment; no further changes | Culture, morphology and biochemistry |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ifrim, Ș.S.; Bârdea, A.; Roman, A.; Soancă, A.; Albu, S.; Gâta, A.; Caloian, C.S.; Cândea, A. Antimicrobial Efficacy and Soft-Tissue Safety of Air-Polishing Powders in Periodontal Therapy: A Narrative Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010009

Ifrim ȘS, Bârdea A, Roman A, Soancă A, Albu S, Gâta A, Caloian CS, Cândea A. Antimicrobial Efficacy and Soft-Tissue Safety of Air-Polishing Powders in Periodontal Therapy: A Narrative Review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleIfrim, Ștefania Sorina, Alina Bârdea, Alexandra Roman, Andrada Soancă, Silviu Albu, Anda Gâta, Carmen Silvia Caloian, and Andreea Cândea. 2026. "Antimicrobial Efficacy and Soft-Tissue Safety of Air-Polishing Powders in Periodontal Therapy: A Narrative Review" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010009

APA StyleIfrim, Ș. S., Bârdea, A., Roman, A., Soancă, A., Albu, S., Gâta, A., Caloian, C. S., & Cândea, A. (2026). Antimicrobial Efficacy and Soft-Tissue Safety of Air-Polishing Powders in Periodontal Therapy: A Narrative Review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010009