Biomaterials for Improving Skin Penetration in Treatment of Skin Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Skin Physiology and Permeability

3. Challenges in Skin Drug Delivery

4. Biomaterials for Skin Cancer Drug Delivery

4.1. Polymeric Nanoparticles

4.2. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers

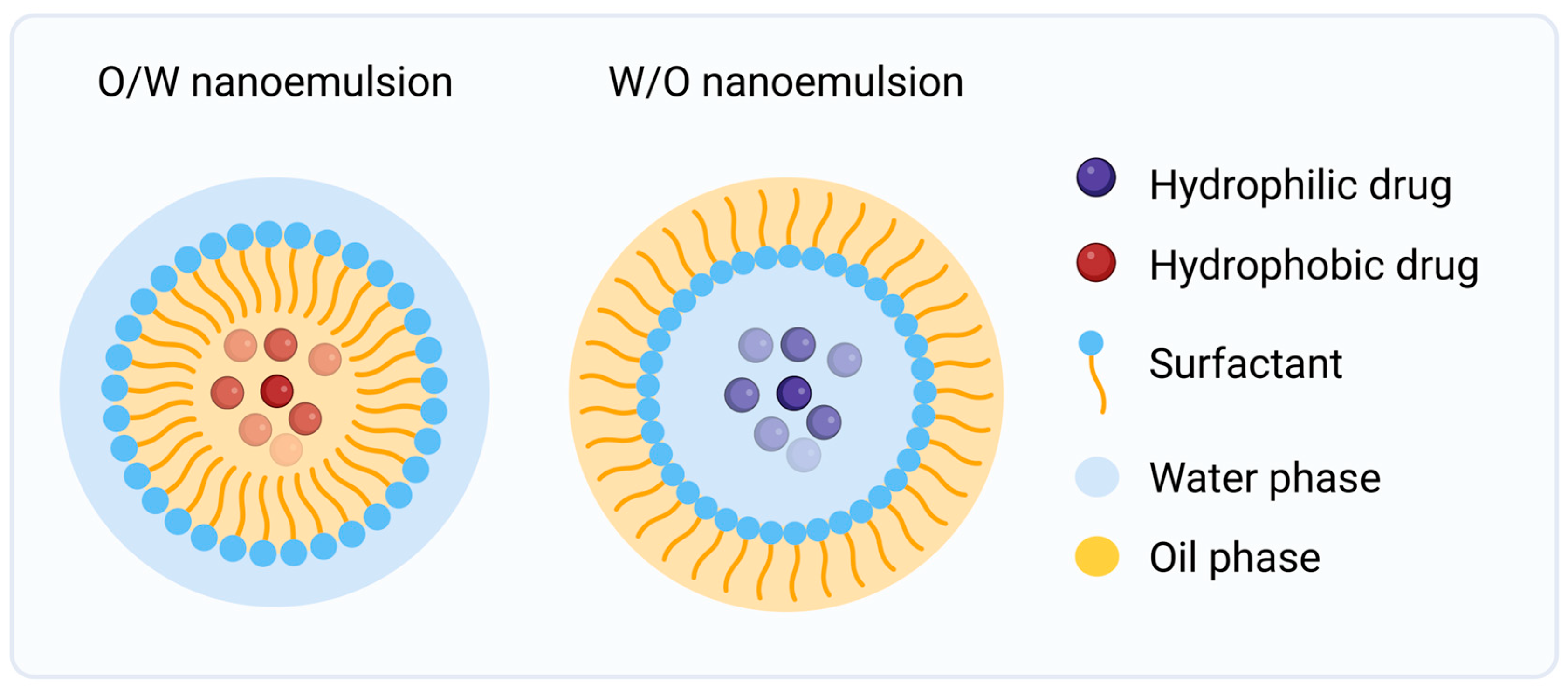

4.2.1. Nanoemulsions

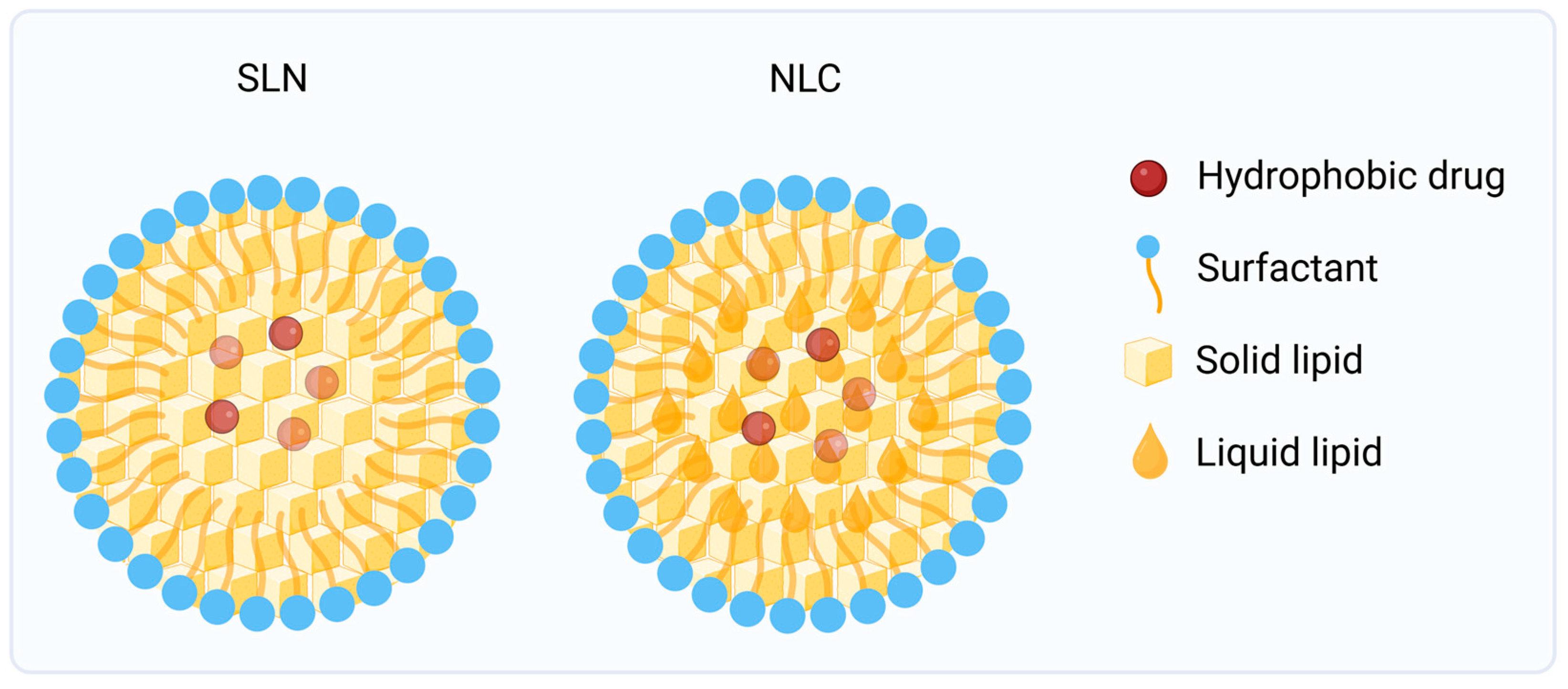

4.2.2. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs)

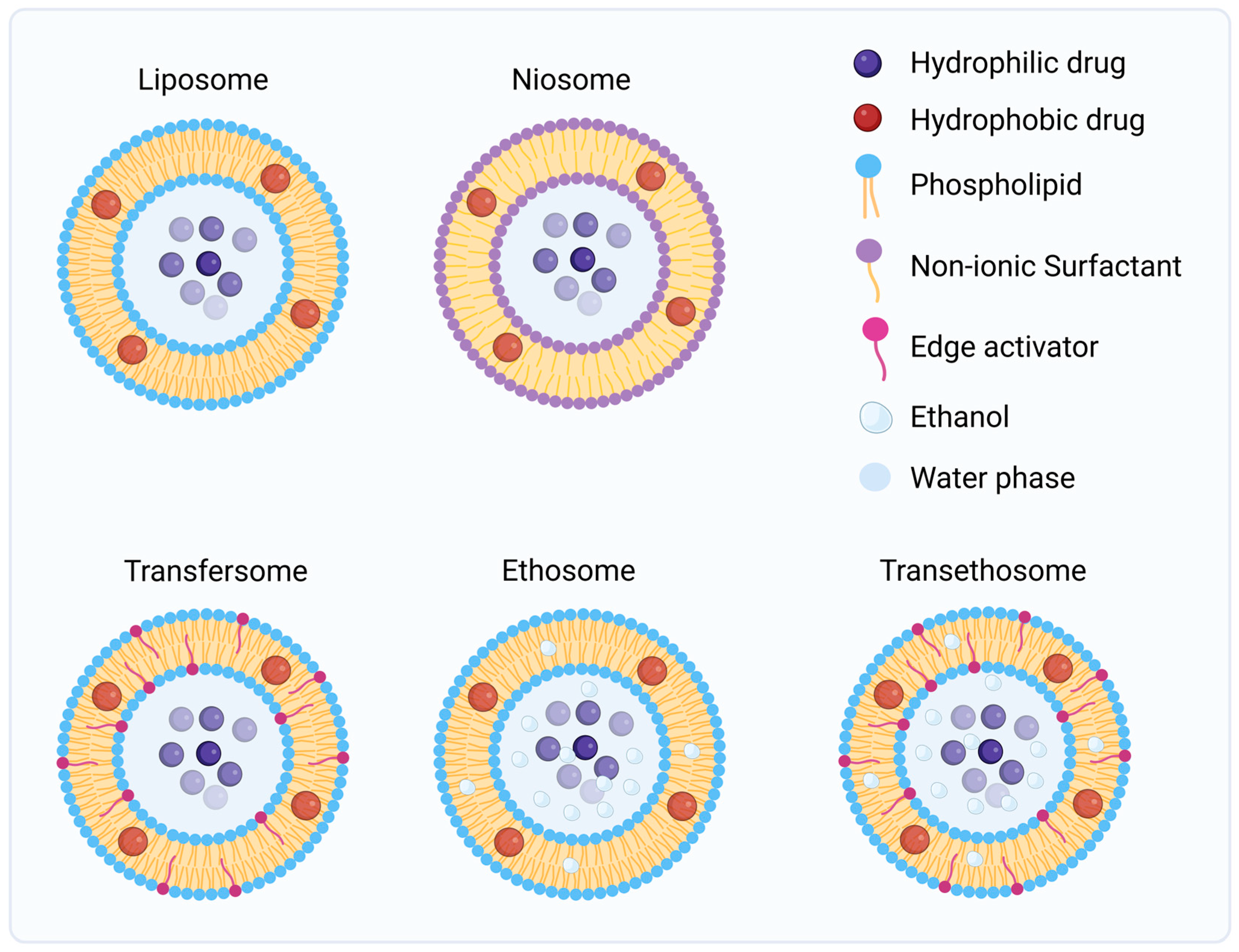

4.2.3. Vesicular Systems

4.3. Hydrogels

4.4. Mechanical and Physical Enhancement Strategies

5. Current and Future Perspectives in Topical Treatment of Skin Cancers

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| AK | Actinic keratoses |

| ALA | 5-aminolevulinic acid |

| BCC | Basal cell Carcinoma |

| GelMA | Gelatin methacryloyl |

| HAMA | Hyaluronic acid methacrylate |

| MAL | Methyl-aminolevulinate |

| MIS | Melanoma in situ |

| NLCs | Nanostructured lipid carriers |

| NMSC | Non-melanoma skin cancers |

| PAA | Poly acrylic acid |

| PCL | Poly ε-caprolactone |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PHEMA | Poly 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| PLA | Poly lactic acid |

| PLGA | Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid |

| PTT | Photothermal therapy |

| PVA | Poly vinyl alcohol |

| sBCC | Superficial basal cell carcinoma |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| SLNs | Solid lipid nanoparticles |

References

- Zhou, L.; Zhong, Y.; Han, L.; Xie, Y.; Wan, M. Global, Regional, and National Trends in the Burden of Melanoma and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roky, A.H.; Islam, M.M.; Ahasan, A.M.F.; Mostaq, M.S.; Mahmud, M.Z.; Amin, M.N.; Mahmud, M.A. Overview of Skin Cancer Types and Prevalence Rates across Continents. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2025, 3, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; De Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centeno, P.P.; Pavet, V.; Marais, R. The Journey from Melanocytes to Melanoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craythorne, E.; Nicholson, P. Diagnosis and Management of Skin Cancer. Medicine 2021, 49, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-Level Classification of Skin Cancer with Deep Neural Networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadendorf, D.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Berking, C.; Griewank, K.G.; Gutzmer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Stang, A.; Roesch, A.; Ugurel, S. Melanoma. Lancet 2018, 392, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassel, J.C.; Heinzerling, L.; Aberle, J.; Bähr, O.; Eigentler, T.K.; Grimm, M.O.; Grünwald, V.; Leipe, J.; Reinmuth, N.; Tietze, J.K.; et al. Combined Immune Checkpoint Blockade (Anti-PD-1/Anti-CTLA-4): Evaluation and Management of Adverse Drug Reactions. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 57, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syn, N.L.; Teng, M.W.L.; Mok, T.S.K.; Soo, R.A. De-Novo and Acquired Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Targeting. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.K.; Simmons, J.L.; Parsons, P.G.; Boyle, G.M. Topical Treatments for Skin Cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 153, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M. Stratum Corneum Defensive Functions: An Integrated View. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korting, H.C.; Schäfer-Korting, M. Carriers in the Topical Treatment of Skin Disease. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2010, 197, 435–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, G.D.; Singh, D. Localized Topical Drug Delivery Systems for Skin Cancer: Current Approaches and Future Prospects. Front. Nanotechnol. 2022, 4, 1006628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.; Williams, A.; Chilcott, R.P.; Brady, B.; Lenn, J.; Evans, C.; Allen, L.; McAuley, W.J.; Beebeejaun, M.; Haslinger, J.; et al. Topically Applied Therapies for the Treatment of Skin Disease: Past, Present, and Future. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 76, 689–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marte, B.; Finkelstein, J.; Anson, L. Skin Biology. Nature 2007, 445, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venus, M.; Waterman, J.; McNab, I. Basic Physiology of the Skin. Surgery 2010, 28, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, K.C. Barrier Function of the Skin: “La Raison d’Être” of the Epidermis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2003, 121, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickett, R.R.; Visscher, M.O. Structure and Function of the Epidermal Barrier. Am. J. Infect. Control 2006, 34, S98–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkreutz, D.; Mirancea, N.; Nischt, R. Basement Membranes in Skin: Unique Matrix Structures with Diverse Functions? Histochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 132, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, E.; Brandner, J.M.; Jensen, J.M. The Skin: An Indispensable Barrier. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 17, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, S.; Ottaviani, M.; Briganti, S.; Di Nardo, A.; Flori, E. The Sebaceous Gland: A Key Player in the Balance Between Homeostasis and Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Cells 2025, 14, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Lu, F.; Feng, J. Aging and Homeostasis of the Hypodermis in the Age-Related Deterioration of Skin Function. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirfel, G.; Herzog, V. Migration of Epidermal Keratinocytes: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Biological Significance. Protoplasma 2004, 223, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Évora, A.S.; Adams, M.J.; Johnson, S.A.; Zhang, Z. Corneocytes: Relationship between Structural and Biomechanical Properties. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 34, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito-Martínez, S.; Salavessa, L.; Raposo, G.; Marks, M.S.; Delevoye, C. Melanin Transfer and Fate within Keratinocytes in Human Skin Pigmentation. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2021, 61, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioce, A.; Cavani, A.; Cattani, C.; Scopelliti, F. Role of the Skin Immune System in Wound Healing. Cells 2024, 13, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadgraft, J. Skin, the Final Frontier. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 224, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Mitragotri, S.; Langer, R. Current Status and Future Potential of Transdermal Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Ma, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Y.; Han, S.; et al. Functional Nano-Systems for Transdermal Drug Delivery and Skin Therapy. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 1527–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevc, G.; Vierl, U. Nanotechnology and the Transdermal Route: A State of the Art Review and Critical Appraisal. J. Control. Release 2010, 141, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal Drug Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.; Phan, K.; Mohammed, Y. Role of Skin Enzymes in Metabolism of Topical Drugs. Metab. Target Organ Damage 2024, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Wendtner, M.H.; Korting, H.C. The PH of the Skin Surface and Its Impact on the Barrier Function. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2006, 19, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.D.; Meinardi, M.M. The 500 Dalton Rule for the Skin Penetration of Chemical Compounds and Drugs. Exp. Dermatol. 2000, 9, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Q.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.F.; Fan, Y. Bin Enhancing Permeation of Drug Molecules Across the Skin via Delivery in Nanocarriers: Novel Strategies for Effective Transdermal Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 646554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedik, L.; Baybekov, S.; Cosnier, F.; Marcou, G.; Varnek, A.; Champmartin, C. An Update of Skin Permeability Data Based on a Systematic Review of Recent Research. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R.O.; Guy, R.H. Predicting Skin Permeability. Pharm. Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Pharm. Sci. 1992, 9, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.P.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, C.W.; Chang, Y.C. Evaluating Molecular Properties Involved in Transport of Small Molecules in Stratum Corneum: A Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship for Skin Permeability. Molecules 2018, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundborg, M.; Wennberg, C.; Lindahl, E.; Norlén, L. Simulating the Skin Permeation Process of Ionizable Molecules. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 5295–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, H.; Ueno, Y.; Hashida, M.; Yamashita, F. Quantitative Prediction of Ionization Effect on Human Skin Permeability. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 522, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, B.; Tutone, M.; Hoffman, E.; Hutter, V.; Almerico, A.M.; Traynor, M. Predicting Skin Permeability by Means of Computational Approaches: Reliability and Caveats in Pharmaceutical Studies. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yourdkhani, A.; Esfandyari-Manesh, M.; Ranjbaran, P.; Amani, M.; Dinarvand, R. Recent Progress in Topical and Transdermal Approaches for Melanoma Treatment. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 1457–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, V.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles for Topical Drug Delivery: Potential for Skin Cancer Treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 153, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.S.; Abdullah Almoyad, M.A.; Wahab, S.; Sahebkar, A.; Gorain, B.; Kaur, H.; Kesharwani, P. Recent Advances in Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for Advanced Skin Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 670, 125203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.H.; Mir, M.; Qian, L.; Baloch, M.; Ali Khan, M.F.; Rehman, A.U.; Ngowi, E.E.; Wu, D.D.; Ji, X.Y. Skin Cancer Biology and Barriers to Treatment: Recent Applications of Polymeric Micro/Nanostructures. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 36, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prow, T.W.; Grice, J.E.; Lin, L.L.; Faye, R.; Butler, M.; Becker, W.; Wurm, E.M.T.; Yoong, C.; Robertson, T.A.; Soyer, H.P.; et al. Nanoparticles and Microparticles for Skin Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011, 63, 470–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.; Swain, S.K.; Das, I.J.; Swain, S.S.; Jena, B.R.; Samal, H.B. Topical Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Skin Cancer: Present Concerns and Challenges. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 114, 107566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H.; Jangde, R.K. Current Updated Review on Preparation of Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications. Next Nanotechnol. 2023, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalan, M.; Shah, P.; Barve, K.; Parekh, K.; Mehta, T.; Patel, P. Skin Cancer Therapeutics: Nano-Drug Delivery Vectors—Present and Beyond. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianzani, C.; Zara, G.P.; Maina, G.; Pettazzoni, P.; Pizzimenti, S.; Rossi, F.; Gigliotti, C.L.; Ciamporcero, E.S.; Daga, M.; Barrera, G. Drug Delivery Nanoparticles in Skin Cancers. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 895986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Yu, B.; Saltzman, W.M.; Girardi, M. Nanoparticles as a Therapeutic Delivery System for Skin Cancer Prevention and Treatment. JID Innov. 2023, 3, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadaei, M.R.; Fadaei, M.S.; Kheirieh, A.E.; Hatami, H.; Rahmanian-Devin, P.; Tayebi-Khorrami, V.; Fathabadi, M.F.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Askari, V.R. Overview of Dendrimers as Promising Drug Delivery Systems with Insight into Anticancer and Anti-Microbial Applications. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 10, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.M.; Jadhav, S.R.; Bryant, G.; Kaur, I.P.; Harding, I.H. On the Formation and Stability Mechanisms of Diverse Lipid-Based Nanostructures for Drug Delivery. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2025, 338, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, Y.; Yoon, J.; Seo, Y.; Han, Y.; Yoo, H.Y.; Sohn, H.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, T. Structure-Centered Design of Lipid-Based Nanocarriers to Overcome Biological Barriers. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Provenza, A.C.; Reverchon, G.; Baldino, L.; Reverchon, E. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers: Bridging Diagnosis and Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pinel, B.; Porras-Alcalá, C.; Ortega-Rodríguez, A.; Sarabia, F.; Prados, J.; Melguizo, C.; López-Romero, J.M. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles: Application and Recent Advances in Cancer Treatment. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.; Bhalodia, D.; Shelat, P. Nanoemulsion: A Pharmaceutical Review. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2010, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidaki, M.D.; Mitsou, E. Advancements in Nanoemulsion-Based Drug Delivery Across Different Administration Routes. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelidari, M.; Abdi-Moghadam, Z.; Sabzevar, T.E.; Khajenouri, M.; Shakeri, A. Preparation and Therapeutic Implications of Essential Oil-Based Nanoemulsions: A Review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 255, 114939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Meher, J.G.; Raval, K.; Khan, F.A.; Chaurasia, M.; Jain, N.K.; Chourasia, M.K. Nanoemulsion: Concepts, Development and Applications in Drug Delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 252, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J. Nanoemulsions versus Microemulsions: Terminology, Differences, and Similarities. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.W.; Gao, P. Emulsions and Microemulsions for Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery. In Handbook of Non-Invasive Drug Delivery Systems; William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Sharma, A.; Sharifi, E.; Damiri, F.; Berrada, M.; Khan, M.A.; Singh, S.K.; Dua, K.; Veiga, F.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; et al. Topical Delivery of Nanoemulsions for Skin Cancer Treatment. Appl. Mater. Today 2023, 35, 102001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.H.; Mäder, K.; Gohla, S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for Controlled Drug Delivery—A Review of the State of the Art. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, W.; Mäder, K. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: Production, Characterization and Applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingayat, V.J.; Zarekar, N.S.; Shendge, R.S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: A Review. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Res. 2017, 4, 67–72. Available online: https://pubs.sciepub.com/nnr/4/2/5/index.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Akbari, J.; Saeedi, M.; Ahmadi, F.; Hashemi, S.M.H.; Babaei, A.; Yaddollahi, S.; Rostamkalaei, S.S.; Asare-Addo, K.; Nokhodchi, A. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Review of the Methods of Manufacture and Routes of Administration. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2022, 27, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, N.; Khatak, S.; Goel, R.K.; Yadav, N.; Vir, U.; Sara, S. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles-A Review. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2013, 5, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, R.H.; Radtke, M.; Wissing, S.A. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) in Cosmetic and Dermatological Preparations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002, 54, S131–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainaga Jyothi, V.G.S.; Ghouse, S.M.; Khatri, D.K.; Nanduri, S.; Singh, S.B.; Madan, J. Lipid Nanoparticles in Topical Dermal Drug Delivery: Does Chemistry of Lipid Persuade Skin Penetration? J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 69, 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcês, A.; Amaral, M.H.; Sousa Lobo, J.M.; Silva, A.C. Formulations Based on Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLC) for Cutaneous Use: A Review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 112, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegas, C.; Patrício, A.B.; Prata, J.M.; Nadhman, A.; Chintamaneni, P.K.; Fonte, P. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles vs. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: A Comparative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Gomes, B.; Cláudia Paiva-Santos, A.; Veiga, F.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F. Beyond the Adverse Effects of the Systemic Route: Exploiting Nanocarriers for the Topical Treatment of Skin Cancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 207, 115197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngokwe, Z.B. Nanotechnology-Based Approaches in Skin Cancer and Its Treatment. In Nanodermatology, Advances in Theory and Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, C.; Cassel, S.; Blanzat, M. Vesicular Systems for Dermal and Transdermal Drug Delivery. RSC Adv. 2020, 11, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, I.A.; Ghate, V.M.; Dsouza, L.; Lewis, S.A. Lipid Vesicles: A Versatile Drug Delivery Platform for Dermal and Transdermal Applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 195, 111262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lila, A.S.A.; Mostafa, M.; Katamesh, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Hassoun, S.M.; El Sayed, M.M.; Subaiea, G.M.; Abdallah, M.H.; Qelliny, M.R. Vesicular Drug Delivery Systems: A Breakthrough in Wound Healing Therapies. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 256, 115046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, A.J.; Martínez-Navarrete, M.; Garrigues, T.M.; Melero, A. Skin Drug Delivery Using Lipid Vesicles: A Starting Guideline for Their Development. J. Control. Release 2023, 355, 624–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolotin, E.M.; Cohen, R.; Bar, L.K.; Emanuel, N.; Ninio, S.; Barenholz, Y.; Lasic, D.D. Ammonium Sulfate Gradients for Efficient and Stable Remote Loading of Amphipathic Weak Bases into Liposomes and Ligandoliposomes. J. Liposome Res. 1994, 4, 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Honeywell-Nguyen, P.L.; Gooris, G.S.; Ponec, M. Structure of the Skin Barrier and Its Modulation by Vesicular Formulations. Prog. Lipid Res. 2003, 42, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Honeywell-Nguyen, P.L. Skin Structure and Mode of Action of Vesicles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002, 54, S41–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeywell-Nguyen, P.L.; Bouwstra, J.A. Vesicles as a Tool for Transdermal and Dermal Delivery. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2005, 2, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M.; Diab, R.; Elaissari, A.; Fessi, H. Lipid Nanocarriers as Skin Drug Delivery Systems: Properties, Mechanisms of Skin Interactions and Medical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevc, G. Lipid Vesicles and Other Colloids as Drug Carriers on the Skin. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 675–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestani, P. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles as a Promising Treatment for the Skin Cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Vaidya, A.; Verma, N. Nano Vesicular Approaches for the Treatment of Skin Cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 685, 126265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, M.; Rehman, U.; Hani, U.; Ramaiah, R.; Gupta, G.; Goh, K.W.; Kesharwani, P. Recent Advances in the Clinical Application of Transferosomes for Skin Cancer Management. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 254, 114877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, M.; Alsawaftah, N.M.; Husseini, G.A. State-of-All-the-Art and Prospective Hydrogel-Based Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoshari, Y. Novel Hydrogels for Topical Applications: An Updated Comprehensive Review Based on Source. Gels 2022, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashist, A.; Vashist, A.; Gupta, Y.K.; Ahmad, S. Recent Advances in Hydrogel Based Drug Delivery Systems for the Human Body. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 2, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zöller, K.; To, D.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Biomedical Applications of Functional Hydrogels: Innovative Developments, Relevant Clinical Trials and Advanced Products. Biomaterials 2025, 312, 122718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, A.; Tian, W.X.; Farooq, M.A.; Khan, D.H. An Overview of Hydrogels and Their Role in Transdermal Drug Delivery. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2021, 70, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Su, J. Fabrication of Physical and Chemical Crosslinked Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 12, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, S. Hydrogels and Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Promoting Refractory Wound Healing: Applications and Prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 285, 138098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkova, M.; Tzankov, B.; Popova, T.; Voycheva, C. Gel Formulations for Topical Treatment of Skin Cancer: A Review. Gels 2023, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnubhakthula, S.; Elupula, R.; Durán-Lara, E.F. Recent Advances in Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery for Melanoma Cancer Therapy: A Mini Review. J. Drug Deliv. 2017, 2017, 7275985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prausnitz, M.R. Microneedles for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004, 56, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.; Mehta, P.; Arshad, M.; Kucuk, I.; Chang, M.W.; Ahmad, Z. Transdermal Microneedles—A Materials Perspective. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdan, I. Microneedle and Drug Delivery across the Skin: An Overview. Pharmacia 2024, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bariya, S.H.; Gohel, M.C.; Mehta, T.A.; Sharma, O.P. Microneedles: An Emerging Transdermal Drug Delivery System. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yu, Q.; Huang, C.; Li, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, D. Microneedles as Transdermal Drug Delivery System for Enhancing Skin Disease Treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 5161–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szunerits, S.; Boukherroub, R. Heat: A Highly Efficient Skin Enhancer for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 342811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Yang, T.; O’Hagan, J.; Zhang, S.; Donnelly, R.F. Photothermal Therapy. J. Control. Release 2020, 325, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, N.; Bali, V.; Baboota, S.; Ahuja, A.; Ali, J. Iontophoresis—An Approach for Controlled Drug Delivery: A Review. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2007, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banga, A.K.; Bose, S.; Ghosh, T.K. Iontophoresis and Electroporation: Comparisons and Contrasts. Int. J. Pharm. 1999, 179, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.; Park, H.; Seo, J.; Lee, S. Sonophoresis in Transdermal Drug Deliverys. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetter, S.M.; Chen, F.W.; Kim, D.D.; Egbert, B.M. Imiquimod 5% Cream as Primary or Adjuvant Therapy for Melanoma in Situ, Lentigo Maligna Type. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globerson, J.A.; Nessel, T.; Basehore, B.M.; Saleeby, E.R. Novel Treatment of In-Transit Metastatic Melanoma with Shave Excision, Electrodesiccation and Curettage, and Topical Imiquimod 5% Cream. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2021, 20, 555–557. Available online: https://jddonline.com/articles/novel-treatment-of-in-transit-metastatic-melanoma-with-shave-excision-electrodesiccation-and-curetta-S1545961621P0555X/ (accessed on 1 December 2025). [PubMed]

- Fernández-Galván, A.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, P.; González-Sixto, B.; Abalde-Pintos, M.T.; Butrón-Bris, B. Topical and Intralesional Immunotherapy for the Management of Basal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, A.M.; Adam, G.P.; Rofeberg, V.; Gazula, A.; Smith, B.; Moustafa, F.; Weinstock, M.A.; Trikalinos, T.A. Treatments of Primary Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovsky, R.L.; Bartenstein, D.W.; Rogers, G.S.; Isakoff, S.J.; Chen, S.T. Photodynamic Therapy for Solid Tumors: A Review of the Literature. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2019, 35, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitouni, N.C.; Bhatia, N.; Ceilley, R.I.; Cohen, J.L.; Del Rosso, J.Q.; Moore, A.Y.; Munavalli, G.; Pariser, D.M.; Schlesinger, T.; Siegel, D.M.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy with 5-Aminolevulinic Acid 10% Gel and Red Light for the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis, Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers, and Acne: Current Evidence and Best Practices. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2021, 14, E53–E65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Micali, G.; Lacarrubba, F.; Dinotta, F.; Massimino, D.; Nasca, M.R. Treating Skin Cancer with Topical Cream. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2010, 11, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasek, N.; Zhou, A.E.; Gronbeck, C.; Jain, N.P.; Balboul, S.; McMullan, P.; Skudalski, L.; Gulati, N.; Ungar, J.; Grant-Kels, J.M.; et al. Minimally-Invasive Modalities for Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer Part II: Treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Savas, J.; Doerfler, L. Nonsurgical Treatments for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Dermatol. Clin. 2019, 37, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.; Saraiva, L.; Marques, A.C.; Amaral, M.H. Skin Cancer Chemoprevention: An Overview. Drug Discov. Today 2025, 30, 104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micali, G.; Lacarrubba, F.; Nasca, M.R.; Ferraro, S.; Schwartz, R.A. Topical Pharmacotherapy for Skin Cancer: Part II. Clinical Applications. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 979.e1–979.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rata, D.M.; Cadinoiu, A.N.; Atanase, L.I.; Popa, M.; Mihai, C.T.; Solcan, C.; Ochiuz, L.; Vochita, G. Topical Formulations Containing Aptamer-Functionalized Nanocapsules Loaded with 5-Fluorouracil—An Innovative Concept for the Skin Cancer Therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 119, 111591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzi, R.P.; Frank, L.A.; Onzi, G.; Pohlmann, A.R.; Guterres, S.S. New Pectin-Based Hydrogel Containing Imiquimod-Loaded Polymeric Nanocapsules for Melanoma Treatment. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 1829–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wen, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhu, L.; Feng, R.; Song, Z. Paclitaxel Skin Delivery by Micelles-Embedded Carbopol 940 Hydrogel for Local Therapy of Melanoma. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 587, 119626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wu, S.; Rietveld, M.; Vermeer, M.; Cruz, L.J.; Eich, C.; El Ghalbzouri, A. Application of Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles Targeting Both Tumor Cells and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts on 3D Human Skin Equivalents Mimicking Melanoma and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Biomater. Adv. 2024, 160, 213831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, F.; Haq, N.; Al-Dhfyan, A.; Alanazi, F.K.; Alsarra, I.A. Chemoprevention of Skin Cancer Using Low HLB Surfactant Nanoemulsion of 5-Fluorouracil: A Preliminary Study. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagne, J.B.; Kakumanu, S.; Nicolosi, R.J. Nanoemulsion Preparations of the Anticancer Drug Dacarbazine Significantly Increase Its Efficacy in a Xenograft Mouse Melanoma Model. Mol. Pharm. 2008, 5, 1055–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, S.; Inostroza-Riquelme, M.; Contreras-Orellana, P.; Diaz-Garcia, V.; Lara, P.; Vivanco-Palma, A.; Cárdenas, A.; Miranda, V.; Robert, P.; Leyton, L.; et al. Curcumin-Loaded Nanoemulsion: A New Safe and Effective Formulation to Prevent Tumor Reincidence and Metastasis. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 22612–22622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, E.H.; Korkmaz, E.; Dellera, E.; Sandri, G.; Cristina Bonferoni, M.; Ozer, O. Resveratrol-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles versus Nanostructured Lipid Carriers: Evaluation of Antioxidant Potential for Dermal Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khallaf, R.A.; Salem, H.F.; Abdelbary, A. 5-Fluorouracil Shell-Enriched Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for Effective Skin Carcinoma Treatment. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 3452–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupal, A.; Sabzichi, M.; Ramezani, F.; Kouhsoltani, M.; Hamishehkar, H. Dermal Delivery of Doxorubicin-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Skin Cancer. J. Microencapsul. 2016, 33, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, R.; Das, P.J.; Pal, P.; Mazumder, B. Topical Delivery of Paclitaxel for Treatment of Skin Cancer. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016, 42, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, A.; Qureshi, O.S.; Kim, H.S.; Cha, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, J.K. Improved Skin Permeation of Methotrexate via Nanosized Ultradeformable Liposomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 3813–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, J.; Guo, F.; Lei, M.; Tan, F.; Li, N. Development of Nanovesicular Systems for Dermal Imiquimod Delivery: Physicochemical Characterization and in Vitro/in Vivo Evaluation. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Liposome Encapsulation of Doxorubicin and Celecoxib in Combination Inhibits Progression of Human Skin Cancer Cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caddeo, C.; Nacher, A.; Vassallo, A.; Armentano, M.F.; Pons, R.; Fernàndez-Busquets, X.; Carbone, C.; Valenti, D.; Fadda, A.M.; Manconi, M. Effect of Quercetin and Resveratrol Co-Incorporated in Liposomes against Inflammatory/Oxidative Response Associated with Skin Cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 513, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pund, S.; Pawar, S.; Gangurde, S.; Divate, D. Transcutaneous Delivery of Leflunomide Nanoemulgel: Mechanistic Investigation into Physicomechanical Characteristics, in Vitro Anti-Psoriatic and Anti-Melanoma Activity. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 487, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Jin, Y.; Qian, X. Transdermal Delivery of the in Situ Hydrogels of Curcumin and Its Inclusion Complexes of Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin for Melanoma Treatment. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 469, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo, L.C.C.F.; Carvalho, G.S.G.; Leal, L.K.A.M.; de Araújo, T.G.; Nogueira, K.A.B.; da Silva, D.A.; de Oliveira Silva Ribeiro, F.; Petrilli, R.; Eloy, J.O. Sorbitan Monolaurate-Containing Liposomes Enhance Skin Cancer Cell Cytotoxicity and in Association with Microneedling Increase the Skin Penetration of 5-Fluorouracil. AAPS PharmSciTech 2022, 23, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, Y.W.; Kumar, A.; Cui, Z. The Effect of Microneedles on the Skin Permeability and Antitumor Activity of Topical 5-Fluorouracil. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2014, 4, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; She, J.; Lin, D.A.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, W.F.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Jin, L.; Xie, X.; Su, Y.X. Microneedle-Mediated Delivery of Lipid-Coated Cisplatin Nanoparticles for Efficient and Safe Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 33060–33069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Fu, M.; Li, Z. Microneedles Loaded with PD-L1 Inhibitor and Doxorubicin GelMA Hydrogel for Melanoma Immunochemotherapy. Mater. Des. 2025, 255, 114238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.S.; Shan, X.; Mao, J.; Qiu, L.; Chen, J. Derma Roller® Microneedles-Mediated Transdermal Delivery of Doxorubicin and Celecoxib Co-Loaded Liposomes for Enhancing the Anticancer Effect. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 99, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemakhavhani, L.; Abrahamse, H.; Dhilip Kumar, S.S. Microneedles for Melanoma Therapy: Exploring Opportunities and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rane, B.; Gawade, S. Transdermal Drug Delivery in Oncology Charting the Road Ahead. Hacet. Univ. J. Fac. Pharm. 2025, 45, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrilli, R.; Eloy, J.O.; Saggioro, F.P.; Chesca, D.L.; de Souza, M.C.; Dias, M.V.S.; daSilva, L.L.P.; Lee, R.J.; Lopez, R.F.V. Skin Cancer Treatment Effectiveness Is Improved by Iontophoresis of EGFR-Targeted Liposomes Containing 5-FU Compared with Subcutaneous Injection. J. Control. Release 2018, 283, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Bonafé, J.M.; Vilalta, A.; Alarcón, I.; Carrera, C.; Puig, S.; Malvehy, J.; Rull, R.; Bennàssar, A. Electrochemotherapy in the Treatment of Melanoma Skin Metastases: A Report on 31 Cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015, 106, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M.; Prow, T.W. Physical Drug Delivery Enhancement for Aged Skin, UV Damaged Skin and Skin Cancer: Translation and Commercialization. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 153, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lele, M.; Kapur, S.; Hargett, S.; Sureshbabu, N.M.; Gaharwar, A.K. Global Trends in Clinical Trials Involving Engineered Biomaterials. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eabq0997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaab, H.O.; Alharbi, F.D.; Alhibs, A.S.; Alanazi, N.B.; Alshehri, B.Y.; Saleh, M.A.; Alshehri, F.S.; Algarni, M.A.; Almugaiteeb, T.; Uddin, M.N.; et al. PLGA-Based Nanomedicine: History of Advancement and Development in Clinical Applications of Multiple Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Clegg, J.R.; Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Hydrogels in the Clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2020, 5, e10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Secci, D.; Urquhart, A.; Bekiaris, V.; Qvortrup, K. Biomaterials for Improving Skin Penetration in Treatment of Skin Cancer. J. Funct. Biomater. 2026, 17, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010039

Secci D, Urquhart A, Bekiaris V, Qvortrup K. Biomaterials for Improving Skin Penetration in Treatment of Skin Cancer. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2026; 17(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleSecci, Davide, Andrew Urquhart, Vasileios Bekiaris, and Katrine Qvortrup. 2026. "Biomaterials for Improving Skin Penetration in Treatment of Skin Cancer" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 17, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010039

APA StyleSecci, D., Urquhart, A., Bekiaris, V., & Qvortrup, K. (2026). Biomaterials for Improving Skin Penetration in Treatment of Skin Cancer. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 17(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb17010039