Does Printing Orientation Matter in PolyJet 3D Printed Teeth for Endodontics? A Micro-CT Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

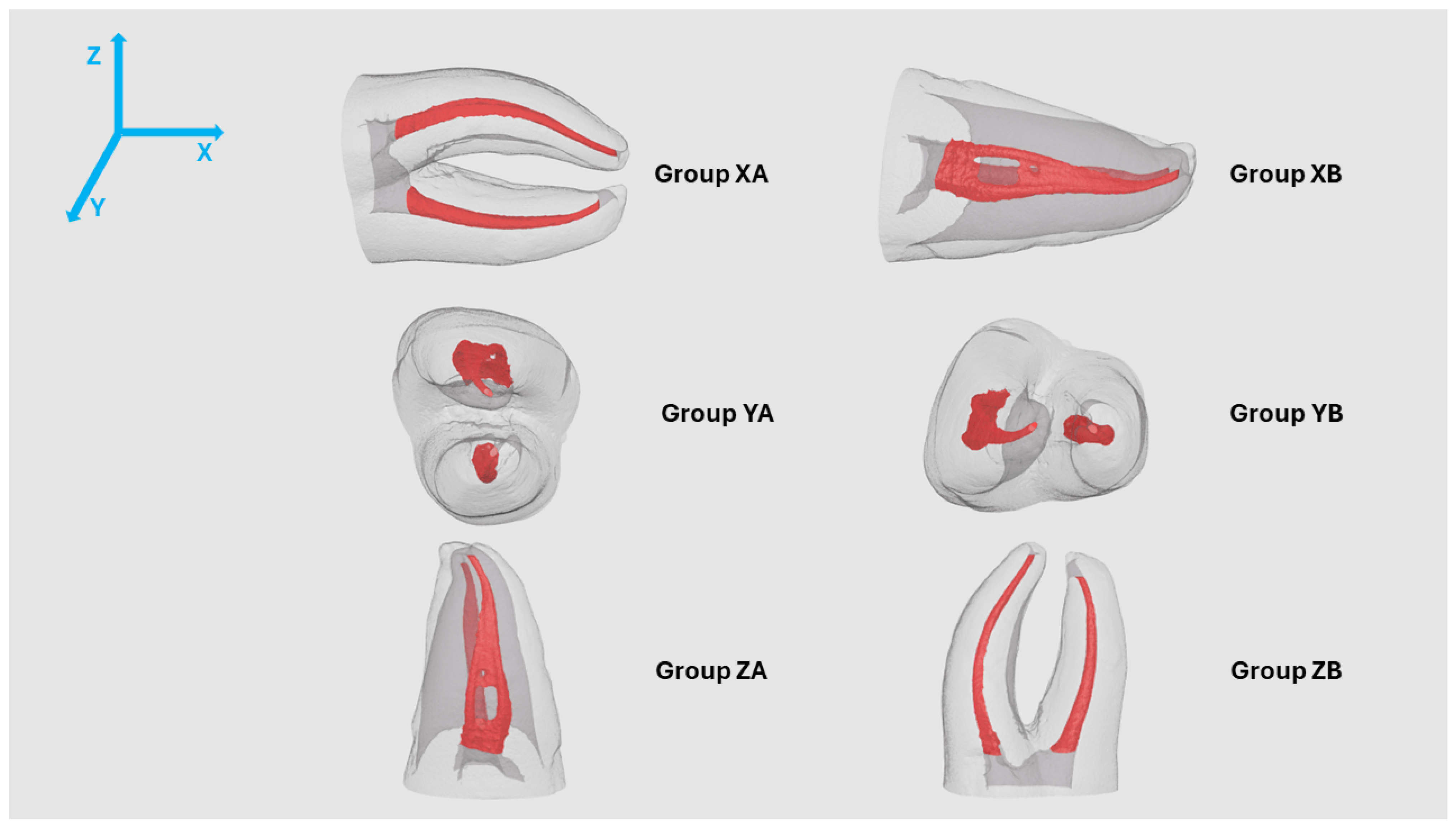

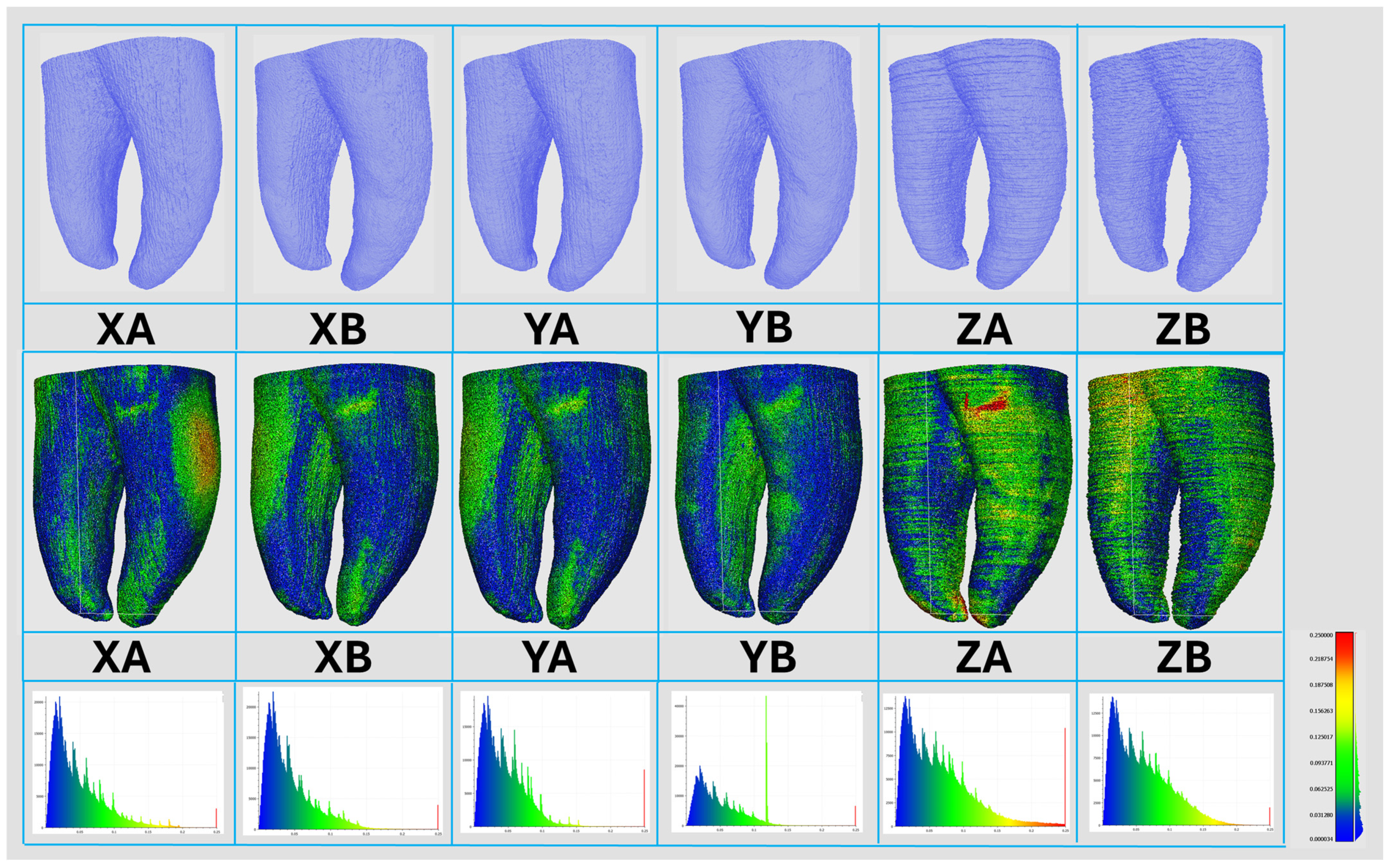

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Natural Specimen Selection

2.2. Root Canal Preparation

2.3. Preparation of 3DPT with PTG

2.4. Micro-CT Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| NT | Natural teeth |

| Micro-CT | Micro-computed tomography |

| PTG | ProTaper Gold® |

| STL | Stereolithography |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| LoA | Limit of agreement |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

References

- Subbaiah, N.K.; Chaudhari, P.K.; Duggal, R.; Samrit, V.D. Effect of print orientation on the dimensional accuracy and cost-effectiveness of rapid-prototyped dental models using a PolyJet photopolymerization printer: An in vitro study. Int. Orthod. 2024, 22, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, M.; Marshall, A.; Catterlin, J.K.; Hornik, T.; Kartalov, E.P. Dimensional Fidelity and Orientation Effects of PolyJet Technology in 3D Printing of Negative Features for Microfluidic Applications. Micromachines 2024, 15, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emiliani, N.; Porcaro, R.; Pisaneschi, G.; Bortolani, B.; Ferretti, F.; Fontana, F.; Campana, G.; Fiorini, M.; Marcelli, E.; Cercenelli, L. Post-printing processing and aging effects on Polyjet materials intended for the fabrication of advanced surgical simulators. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 156, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazón, A.; Morer, P.; Matey, L. PolyJet technology for product prototyping: Tensile strength and surface roughness properties. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 228, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, T.; Barbosa, C.; Franco, M.; Silva, R.; Alves, N.; Castelo-Baz, P.; Martin-Cruces, J.; Martin-Biedma, B. Three-Dimensional Printed Teeth in Endodontics: A New Protocol for Microcomputed Tomography Studies. Materials 2024, 17, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, N.J.; Jolivet, L.; O’Neill, P.; Brabazon, D. An evaluation of components manufactured from a range of materials, fabricated using PolyJet technology. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 3, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclift, M.; Williams, C. Examining variability in the mechanical properties of parts manufactured via polyjet direct 3D printing. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium—An Additive Manufacturing Conference, SFF 2012, Austin, TX, USA, 6–8 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K.H.; Oberoi, G.; Unger, E.; Janjic, K.; Rohringer, S.; Heber, S.; Agis, H.; Schedle, A.; Kiss, H.; Podesser, B.K.; et al. Medical 3D printing with polyjet technology: Effect of material type and printing orientation on printability, surface structure and cytotoxicity. 3D Print. Med. 2023, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezek, L.; Meisel, N.; Williams, C. Exploring variability of orientation and aging effects in material properties of multi-material jetting parts. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2016, 22, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.; Gurunathan, S.K. An experimental and theoretical investigation of surface roughness of poly-jet printed parts. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2015, 10, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghauli, M.A.; Almuzaini, S.A.; Aljohani, R.; Alqutaibi, A.Y. Impact of 3D printing orientation on accuracy, properties, cost, and time efficiency of additively manufactured dental models: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.; Shea, K.; Daraio, C. Mechanical properties of parts fabricated with inkjet 3D printing through efficient experimental design. Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 902–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, J.; Stavropoulos, P.; Koutsomichalis, A.; Ntintakis, I.; Vaxevanidis, N. Dimensional Accuracy Optimization of Prototypes produced by PolyJet Direct 3D Printing Technology. Adv. Eng. Mech. Mater. 2014, 978, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, T.; Barbosa, C.; Franco, M.; Baptista, C.; Alves, N.; Castelo-Baz, P.; Martin-Cruces, J.; Martin-Biedma, B. 3D-Printed Teeth in Endodontics: Why, How, Problems and Future-A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Deus, G.; Simoes-Carvalho, M.; Belladonna, F.G.; Versiani, M.A.; Silva, E.; Cavalcante, D.M.; Souza, E.M.; Johnsen, G.F.; Haugen, H.J.; Paciornik, S. Creation of well-balanced experimental groups for comparative endodontic laboratory studies: A new proposal based on micro-CT and in silico methods. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 974–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reymus, M.; Fotiadou, C.; Kessler, A.; Heck, K.; Hickel, R.; Diegritz, C. 3D printed replicas for endodontic education. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolling, M.; Backhaus, J.; Hofmann, N.; Kess, S.; Krastl, G.; Soliman, S.; Konig, S. Students’ perception of three-dimensionally printed teeth in endodontic training. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2022, 26, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesario, S.; Rizzo, G.; Manso, M.C.; Barbosa, C.; Gavinha, S.; Reis, T. Student’s Perception Towards Endodontic Training with Artificial Teeth: What Has Changed? Eur. Endod. J. 2025, 10, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsmann, M. A critical appraisal of research methods and experimental models for studies on root canal preparation. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, J.; Versiani, M.A.; de Sousa-Neto, M.D.; Plazas-Garzon, A.; Basrani, B. Evaluation of the Shaping Characteristics of ProTaper Gold, ProTaper NEXT, and ProTaper Universal in Curved Canals. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 1718–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, A.; Yang, Y.; Li, L. Dimensional Performance of As-Built Assemblies in Polyjet Additive Manufacturing Process. In Proceedings of the ASME 2017 12th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 4–8 June 2017; p. V002T001A039. [Google Scholar]

- Mendřický, R. Accuracy analysis of additive technique for parts manufacturing. MM Sci. J. 2016, 2016, 1502–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebong, R.E.; Stewart, K.T.; Utreja, A.; Ghoneima, A.A. Accuracy of three-dimensional dental resin models created by fused deposition modeling, stereolithography, and Polyjet prototype technologies: A comparative study. Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Cho, J.W.; Chang, N.Y.; Chae, J.M.; Kang, K.H.; Kim, S.C.; Cho, J.H. Accuracy of three-dimensional printing for manufacturing replica teeth. Korean J. Orthod. 2015, 45, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Ajuz, N.C.; Martins, J.N.R.; Antunes, B.R.; Lima, C.O.; Vieira, V.T.L.; Braz-Fernandes, F.M.; Versiani, M.A. Multimethod analysis of three rotary instruments produced by electric discharge machining technology. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazzouzi-Raiss, K.; Ramirez-Munoz, A.; Mendez, S.P.; Vieira, G.C.S.; Aranguren, J.; Perez, A.R. Effects of Conservative Access and Apical Enlargement on Shaping and Dentin Preservation with Traditional and Modern Instruments: A Micro-computed Tomographic Study. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, J.A.; Vivan, R.R.; Cavenago, B.C.; Amoroso-Silva, P.A.; Bernardes, R.A.; Vasconcelos, B.C.; Duarte, M.A. Influence of NiTi alloy on the root canal shaping capabilities of the ProTaper Universal and ProTaper Gold rotary instrument systems. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2017, 25, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.; Nawal, R.; Talwar, S.; Baveja, C.P.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, S. Shaping, and disinfecting abilities of ProTaper Universal, ProTaper Gold, and Twisted Files: A correlative microcomputed tomographic and bacteriologic analysis. Endodontology 2023, 35, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, O.A.; Laib, A.; Gohring, T.N.; Barbakow, F. Changes in root canal geometry after preparation assessed by high-resolution computed tomography. J. Endod. 2001, 27, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Tooth | 3D Printed Teeth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XA | XB | YA | YB | ZA | ZB | |||

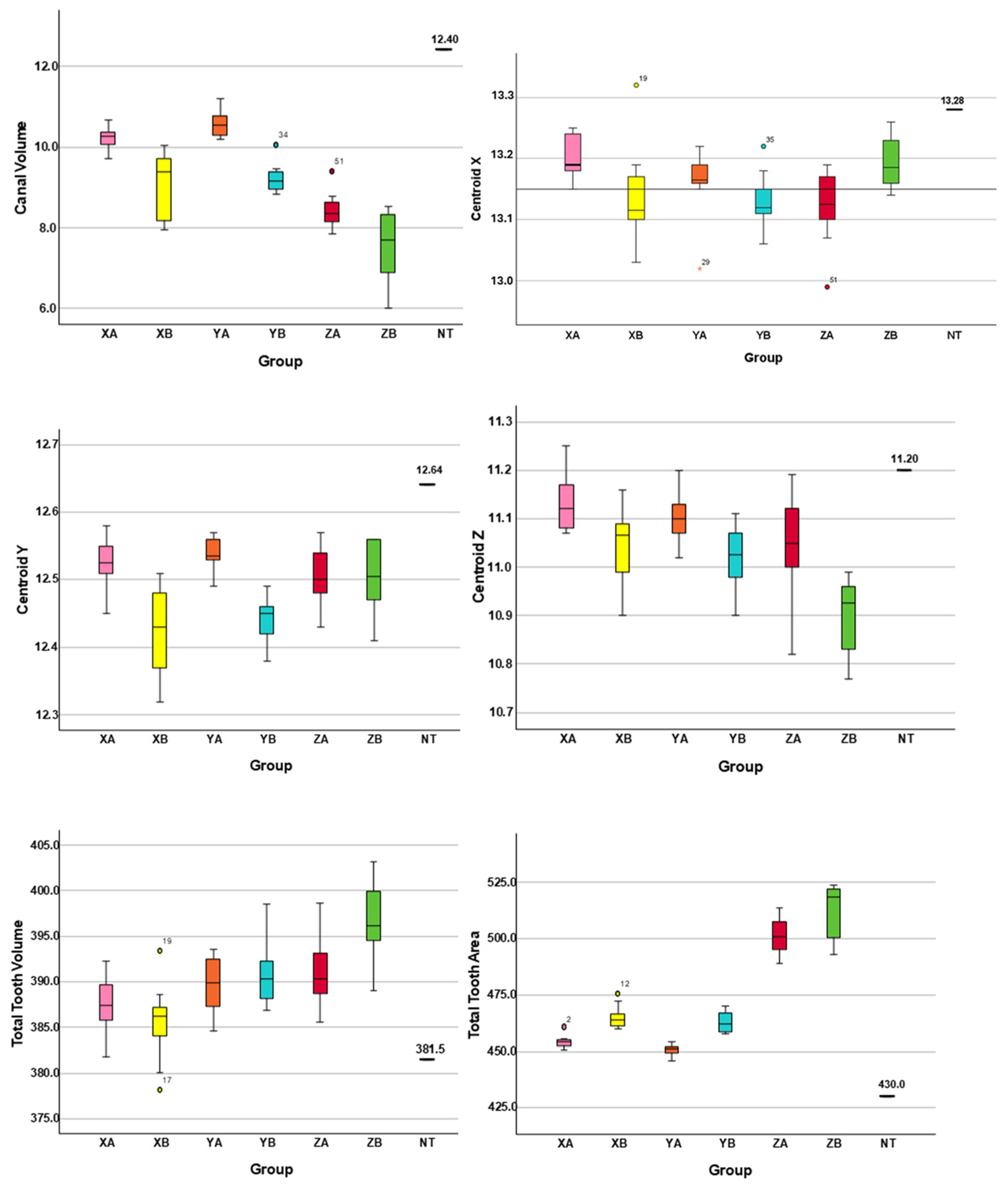

| Canal Volume (mm3) | 12.40 | Mean ± SD | 10.23 ± 0.31 | 9.02 ± 0.81 | 10.58 ± 0.31 | 9.22 ± 0.36 | 8.44 ± 0.44 | 7.59 ± 0.86 |

| Median | 10.28 | 9.38 | 10.54 | 9.15 | 8.37 | 7.70 | ||

| Min–Max | 9.72–10.67 | 7.96–10.04 | 10.19–11.19 | 8.82–10.06 | 7.85–9.40 | 6.00–8.54 | ||

| Centroid X (mm) | 13.28 | Mean ± SD | 13.20 ± 0.03 | 13.13 ± 0.08 | 13.16 ± 0.05 | 13.13 ± 0.04 | 13.12 ± 0.06 | 13.19 ± 0.04 |

| Median | 13.20 | 13.12 | 13.17 | 13.12 | 13.13 | 13.19 | ||

| Min–Max | 13.15–13.25 | 13.03–13.32 | 13.02–13.22 | 13.03–13.22 | 12.99–13.19 | 13.14–13.26 | ||

| Centroid Y (mm) | 12.64 | Mean ± SD | 12.52 ± 0.04 | 12.42 ± 0.06 | 12.54 ± 0.02 | 12.45 ± 0.03 | 12.51 ± 0.05 | 12.50 ± 0.05 |

| Median | 12.53 | 12.43 | 12.54 | 12.45 | 12.50 | 12.51 | ||

| Min–Max | 12.45–12.58 | 12.32–12.51 | 12.49–12.57 | 12.38–12.49 | 12.43–12.57 | 12.41–12.56 | ||

| Centroid Z (mm) | 11.20 | Mean ± SD | 11.13 ± 0.06 | 11.05 ± 0.08 | 11.10 ± 0.05 | 11.02 ± 0.07 | 11.05 ± 0.11 | 10.89 ± 0.08 |

| Median | 11.12 | 11.07 | 11.10 | 11.03 | 11.05 | 10.93 | ||

| Min–Max | 11.07–11.25 | 10.90–11.16 | 11.02–11.20 | 10.90–11.11 | 10.82–11.19 | 10.77–10.99 | ||

| Total Tooth Volume (mm3) | 381.45 | Mean ± SD | 387.56 ± 3.23 | 385.55 ± 4.31 | 389.27 ± 3.19 | 391.10 ± 3.96 | 391.10 ± 3.91 | 396.45 ± 4.77 |

| Median | 387.40 | 386.27 | 389.87 | 390.31 | 390.38 | 396.19 | ||

| Min–Max | 381.75–392.30 | 378.20–393.45 | 384–393.54 | 386.90–398.51 | 385.53–398.64 | 389.07–403.15 | ||

| Total Tooth Area (mm2) | 430.00 | Mean ± SD | 454.24 ± 2.85 | 465.30 ± 5.21 | 450.72 ± 2.65 | 463.01 ± 4.55 | 500.76 ± 8.15 | 512.41 ± 11.69 |

| Median | 454.16 | 463.97 | 451.11 | 462.18 | 500.90 | 518.71 | ||

| Min–Max | 450.60–460.84 | 459.86–475.78 | 445.82–454.30 | 457.65–469.99 | 488.93–513.79 | 492.84–523.89 | ||

| 3D Printed Teeth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XA | XB | YA | YB | ZA | ZB | ||

| Canal Volume (mm3) | Bias | −2.17 | −3.38 | −1.83 | −3.18 | −3.96 | −4.81 |

| 95% LoA | −2.78 to −1.56 | −4.97 to −1.79 | −2.44 to −1.22 | −3.89 to −2.47 | −4.82 to −3.10 | −6.50 to −3.12 | |

| Centroid X (mm) | Bias | −0.08 | −0.15 | −0.12 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.09 |

| 95% LoA | −0.14 to −0.02 | −0.31 to 0.01 | −0.22 to −0.02 | −0.23 to −0.07 | −0.28 to −0.04 | −0.17 to −0.01 | |

| Centroid Y (mm) | Bias | −0.12 | −0.22 | −0.10 | −0.19 | −0.14 | −0.14 |

| 95% LoA | −0.20 to −0.04 | −0.34 to −0.10 | −0.14 to −0.06 | −0.25 to −0.13 | −0.24 to −0.04 | −0.24 to −0.04 | |

| Centroid Z (mm) | Bias | −0.07 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.18 | −0.15 | −0.31 |

| 95% LoA | −0.19 to 0.05 | −0.31 to 0.01 | −0.20 to 0.00 | −0.32 to −0.04 | −0.37 to 0.07 | −0.47 to −0.15 | |

| Total Tooth Volume (mm3) | Bias | 6.11 | 4.10 | 7.82 | 9.65 | 9.65 | 15.00 |

| 95% LoA | −0.22 to 12.44 | −4.35 to 12.55 | 1.57 to 14.07 | 1.89 to 17.41 | 1.99 to 17.31 | 5.65 to 24.35 | |

| Total Tooth Area (mm2) | Bias | 24.24 | 35.30 | 20.72 | 33.01 | 70.76 | 82.41 |

| 95% LoA | 18.65 to 29.83 | 25.09 to 45.51 | 15.53 to 25.91 | 24.09 to 41.93 | 54.79 to 86.73 | 59.50 to 105.32 | |

| Canal Volume (%) | Bias | −17.52 | −27.24 | −14.78 | −25.66 | −31.94 | −38.80 |

| 95% LoA | −22.48 to −12.56 | −40.06 to −14.42 | −19.72 to −9.84 | −31.42 to −19.90 | −38.82 to −25.06 | −52.38 to −25.22 | |

| Centroid X (%) | Bias | −0.59 | −1.11 | −0.90 | −1.11 | −1.22 | −0.66 |

| 95% LoA | −1.10 to −0.08 | −2.31 to 0.09 | −1.70 to −0.10 | −1.76 to −0.46 | −2.08 to −0.36 | −1.31 to −0.01 | |

| Centroid Y (%) | Bias | −0.07 | −1.72 | −0.81 | −1.53 | −1.07 | −1.12 |

| 95% LoA | −0.19 to 0.05 | −2.66 to −0.78 | −1.16 to −0.46 | −2.04 to −1.02 | −1.81 to −0.33 | −1.96 to −0.28 | |

| Centroid Z (%) | Bias | −0.60 | −1.31 | −0.88 | −1.64 | −1.35 | −2.74 |

| 95% LoA | −1.58 to 0.38 | −2.64 to 0.02 | −1.74 to −0.02 | −2.82 to −0.46 | −3.19 to −0.49 | −4.15 to −1.33 | |

| Total Tooth Volume (%) | Bias | 1.60 | 1.08 | 2.05 | 2.53 | 2.53 | 3.93 |

| 95% LoA | −0.07 to −3.27 | −1.13 to 3.29 | 0.40 to 3.70 | 0.51 to 4.55 | 0.53 to 4.53 | 1.48 to 6.38 | |

| Total Tooth Area (%) | Bias | 5.64 | 8.21 | 4.82 | 7.68 | 16.46 | 19.16 |

| 95% LoA | 4.35 to 6.93 | 5.84 to 10.58 | 3.60 to 6.04 | 5.60 to 9.76 | 12.74 to 20.18 | 13.83 to 24.49 | |

| 3D Printed Teeth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XA | XB | YA | YB | ZA | ZB | ||

| Total Tooth Volume (mm3) | Mean ± SD | 387.56 ± 3.23 | 385.55 ± 4.31 | 389.27 ± 3.19 | 391.10 ± 3.96 | 391.10 ± 3.91 | 396.45 ± 4.77 |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.83 | 1.12 | 0.82 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.20 | |

| Total Tooth Area (mm2) | Mean ± SD | 454.24 ± 2.85 | 465.30 ± 5.21 | 450.72 ± 2.65 | 463.01 ± 4.55 | 500.76 ± 8.15 | 512.41 ± 11.69 |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.63 | 1.12 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 1.63 | 2.28 | |

| XA | YA | XB | YB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

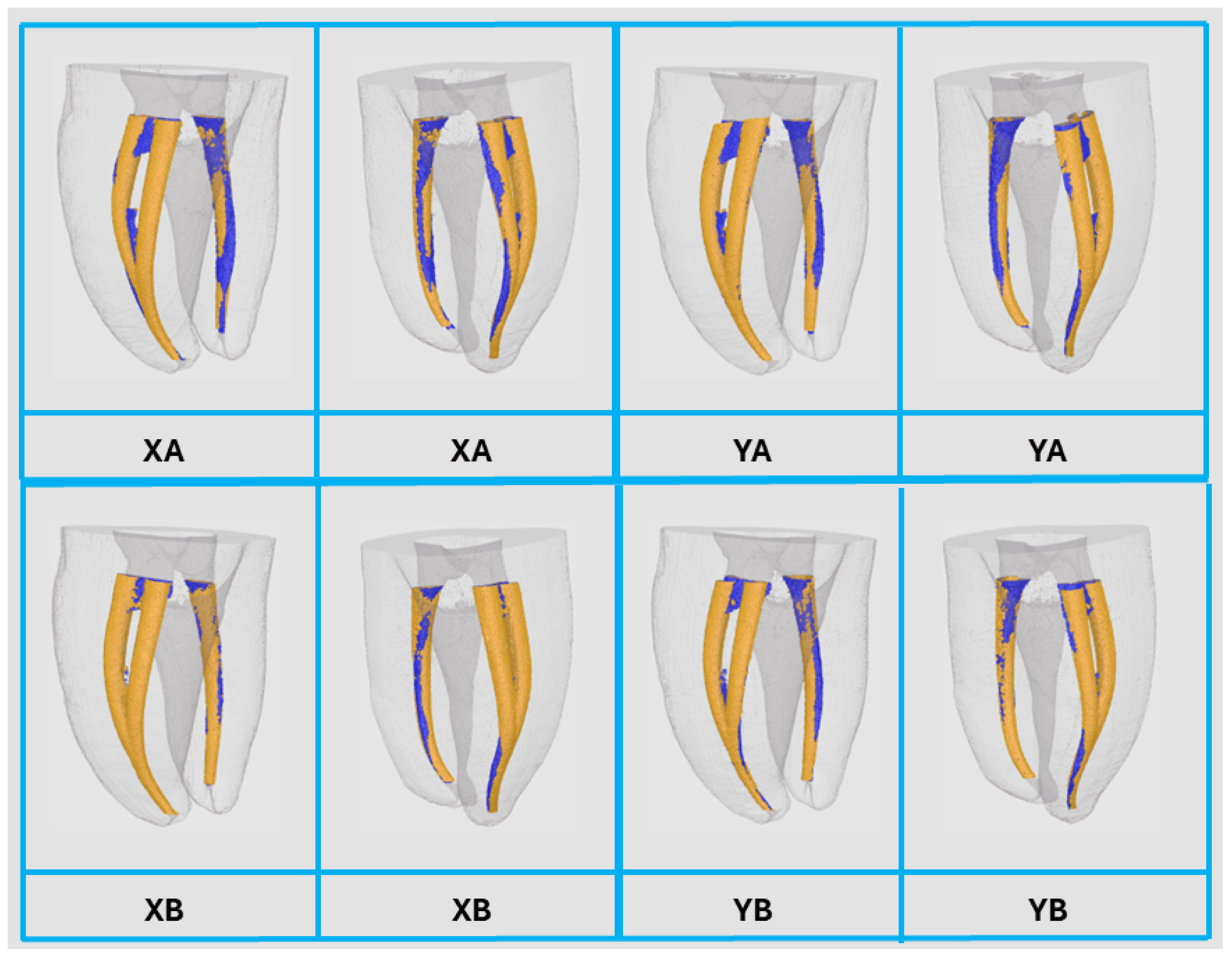

| Canal Volume (mm3) | Initial | Mean ± SD | 10.23 ± 0.31 | 10.58 ± 0.31 | 9.02 ± 0.81 | 9.22 ± 0.36 |

| Min–Max | 9.72–10.67 | 10.19–11.19 | 7.96–10.04 | 8.82–10.06 | ||

| After | Mean ± SD | 17.97 ± 0.52 | 18.25 ± 0.50 | 17.05 ± 0.58 | 16.63 ± 0.36 | |

| Min–Max | 17.20–18.73 | 17.21–18.83 | 16.32–18.22 | 16.19–17.49 | ||

| % Volume Increase | Mean ± SD | 75.87 ± 7.20 | 72.87 ± 7.72 | 90.14 ± 16.12 | 80.18 ± 8.35 | |

| Min–Max | 63.54–86.34 | 53.80–81.94 | 71.79–112.27 | 63.12–90.82 | ||

| Centroid X (mm) | Initial | Mean ± SD | 13.20 ± 0.03 | 13.16 ± 0.05 | 13.13 ± 0.08 | 13.13 ± 0.04 |

| Min–Max | 13.15–13.25 | 13.02–13.22 | 13.03–13.32 | 13.03–13.22 | ||

| After | Mean ± SD | 13.66 ± 0.04 | 13.64 ± 0.03 | 13.60 ± 0.05 | 13.61 ± 0.03 | |

| Min–Max | 13.58–13.72 | 13.59–13.70 | 13.52–13.70 | 13.56–13.68 | ||

| Deviation | Mean ± SD | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.12 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | |

| Min–Max | 0.39–0.54 | 0.41–0.63 | 0.20–0.58 | 0.41–0.54 | ||

| Centroid Y (mm) | Initial | Mean ± SD | 12.52 ± 0.04 | 12.54 ± 0.02 | 12.42 ± 0.06 | 12.45 ± 0.03 |

| Min–Max | 12.45–12.58 | 12.49–12.57 | 12.32–12.51 | 12.38–12.49 | ||

| After | Mean ± SD | 12.99 ± 0.03 | 13.02 ± 0.02 | 12.93 ± 0.06 | 12.99 ± 0.05 | |

| Min–Max | 12.92–13.02 | 12.98–13.07 | 12.86–13.03 | 12.95–13.11 | ||

| Deviation | Mean ± SD | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | |

| Min–Max | 0.34–0.55 | 0.42–0.54 | 0.42–0.62 | 0.48–0.61 | ||

| Centroid Z (mm) | Initial | Mean ± SD | 11.13 ± 0.06 | 11.10 ± 0.05 | 11.05 ± 0.08 | 11.02 ± 0.07 |

| Min–Max | 11.07–11.25 | 11.02–11.20 | 10.90–11.16 | 10.90–11.11 | ||

| After | Mean ± SD | 11.44 ± 0.04 | 11.45 ± 0.04 | 11.45 ± 0.05 | 11.40 ± 0.04 | |

| Min–Max | 11.35–11.48 | 11.38–11.53 | 11.34–11.50 | 11.35–11.48 | ||

| Deviation | Mean ± SD | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | |

| Min–Max | 0.20–0.41 | 0.23–0.45 | 0.26–0.57 | 0.28–0.47 | ||

| Canal Transportation (mm) | Mean ± SD | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 0.82 ± 0.08 | |

| Min–Max | 0.57–0.84 | 0.66–0.86 | 0.64–0.94 | 0.73–0.97 | ||

| Unprepared area (%) | Mean ± SD | 36.93 ± 2.99 | 38.18 ± 3.82 | 35.37 ± 5.48 | 38.86 ± 5.01 | |

| Min–Max | 32.89–42.24 | 31.96–44.58 | 28.59–49.29 | 31.86–49.98 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbosa, C.; Reis, T.; Reis, J.B.; Franco, M.; Batista, C.; Ruben, R.B.; Martín-Biedma, B.; Martín-Cruces, J. Does Printing Orientation Matter in PolyJet 3D Printed Teeth for Endodontics? A Micro-CT Analysis. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120471

Barbosa C, Reis T, Reis JB, Franco M, Batista C, Ruben RB, Martín-Biedma B, Martín-Cruces J. Does Printing Orientation Matter in PolyJet 3D Printed Teeth for Endodontics? A Micro-CT Analysis. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):471. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120471

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbosa, Cláudia, Tiago Reis, José B. Reis, Margarida Franco, Catarina Batista, Rui B. Ruben, Benjamín Martín-Biedma, and Jose Martín-Cruces. 2025. "Does Printing Orientation Matter in PolyJet 3D Printed Teeth for Endodontics? A Micro-CT Analysis" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120471

APA StyleBarbosa, C., Reis, T., Reis, J. B., Franco, M., Batista, C., Ruben, R. B., Martín-Biedma, B., & Martín-Cruces, J. (2025). Does Printing Orientation Matter in PolyJet 3D Printed Teeth for Endodontics? A Micro-CT Analysis. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 471. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120471