3D-Printed Multifunctional Multicompartment Polymer-Based Capsules for Tunable and Spatially Controlled Drug Release

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Bioink and Polymer Preparation

2.3. Capsule Biofabrication

2.4. Morphology and Mechanical Testing

2.5. Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy

2.6. Release Assay, Storage Stability, and Compartmentalization Efficacy

2.7. Numerical Simulation (Finite Element Method, FEM)

3. Results

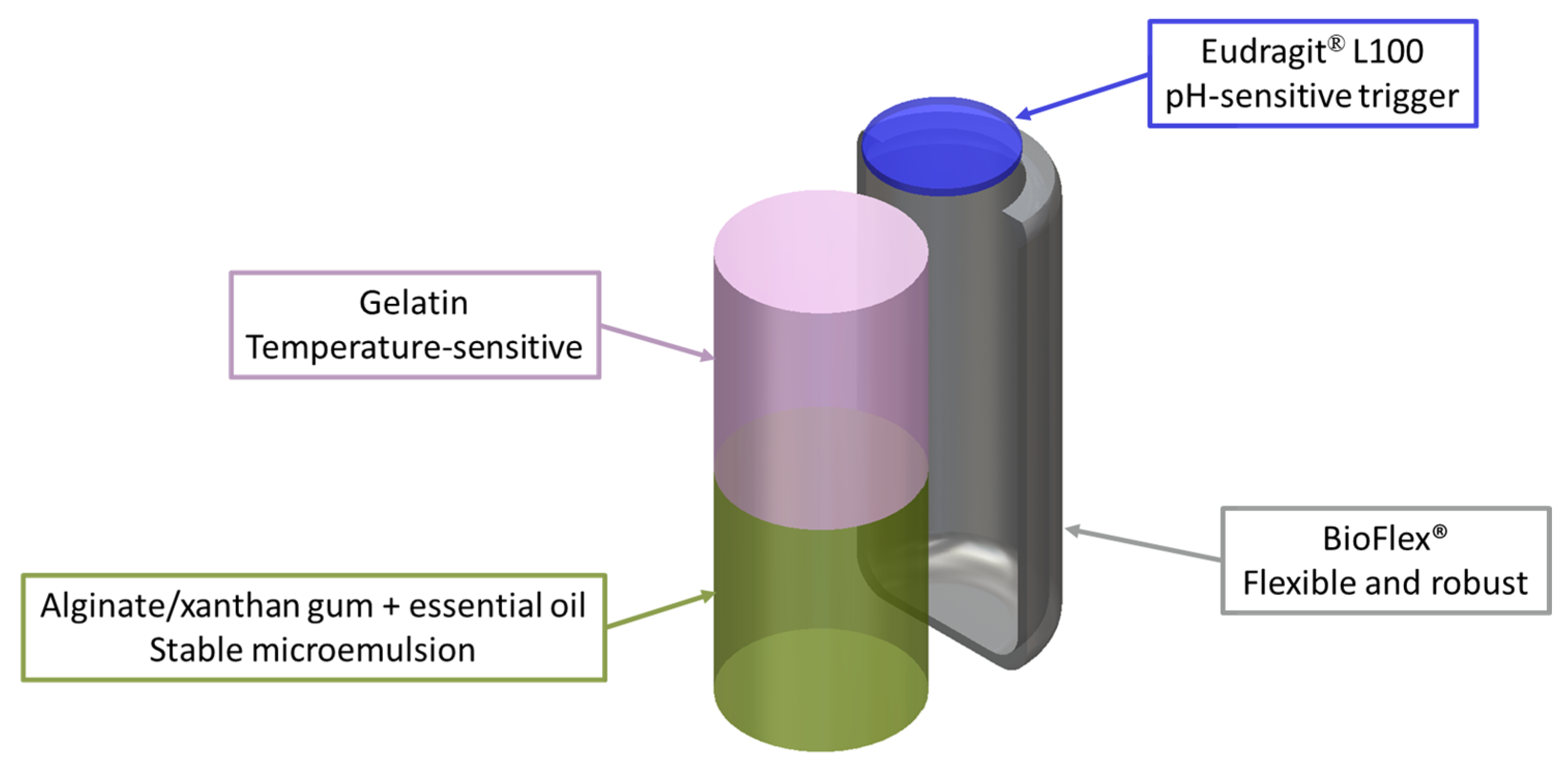

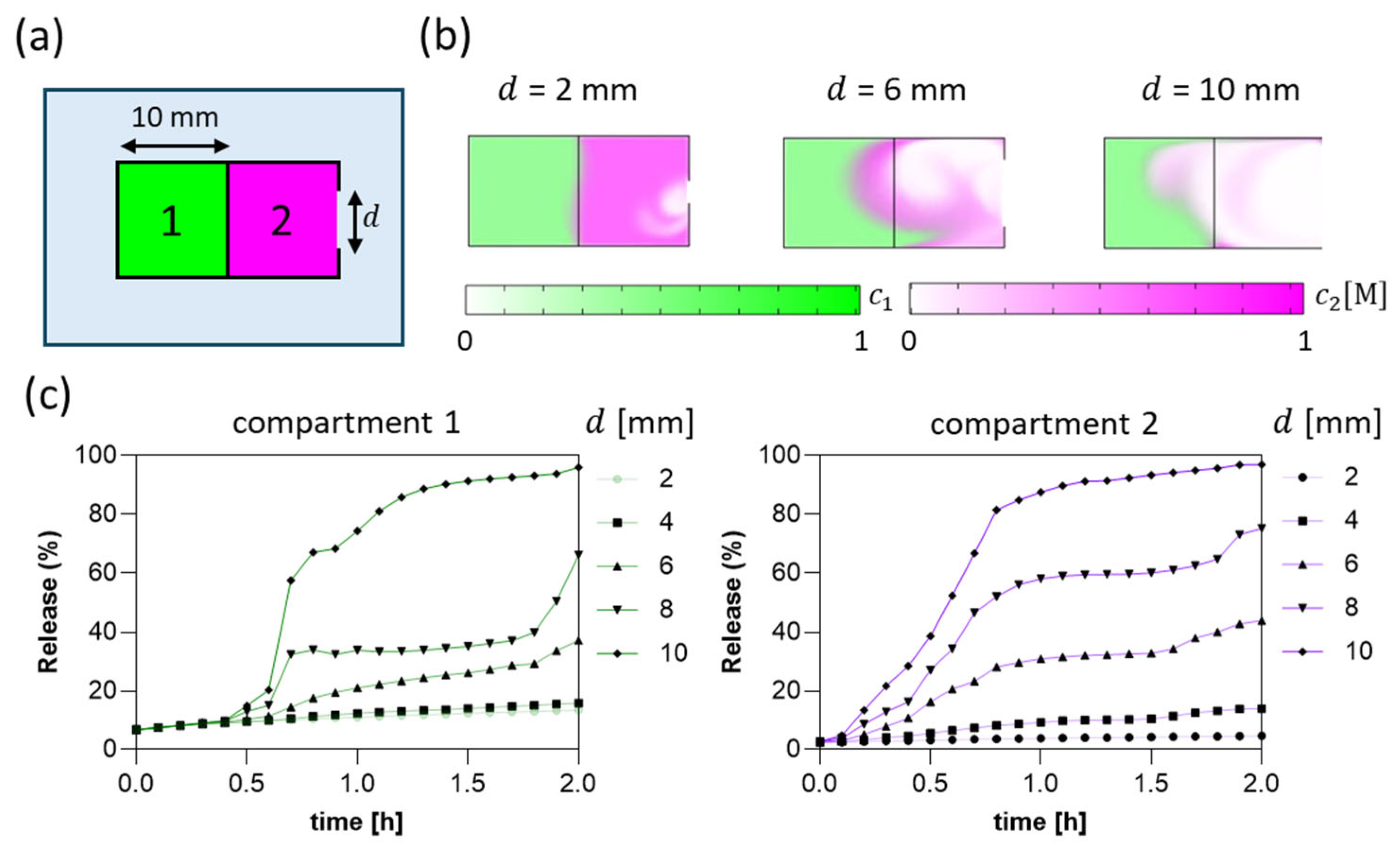

3.1. Numerical Simulation-Driven Capsule Design

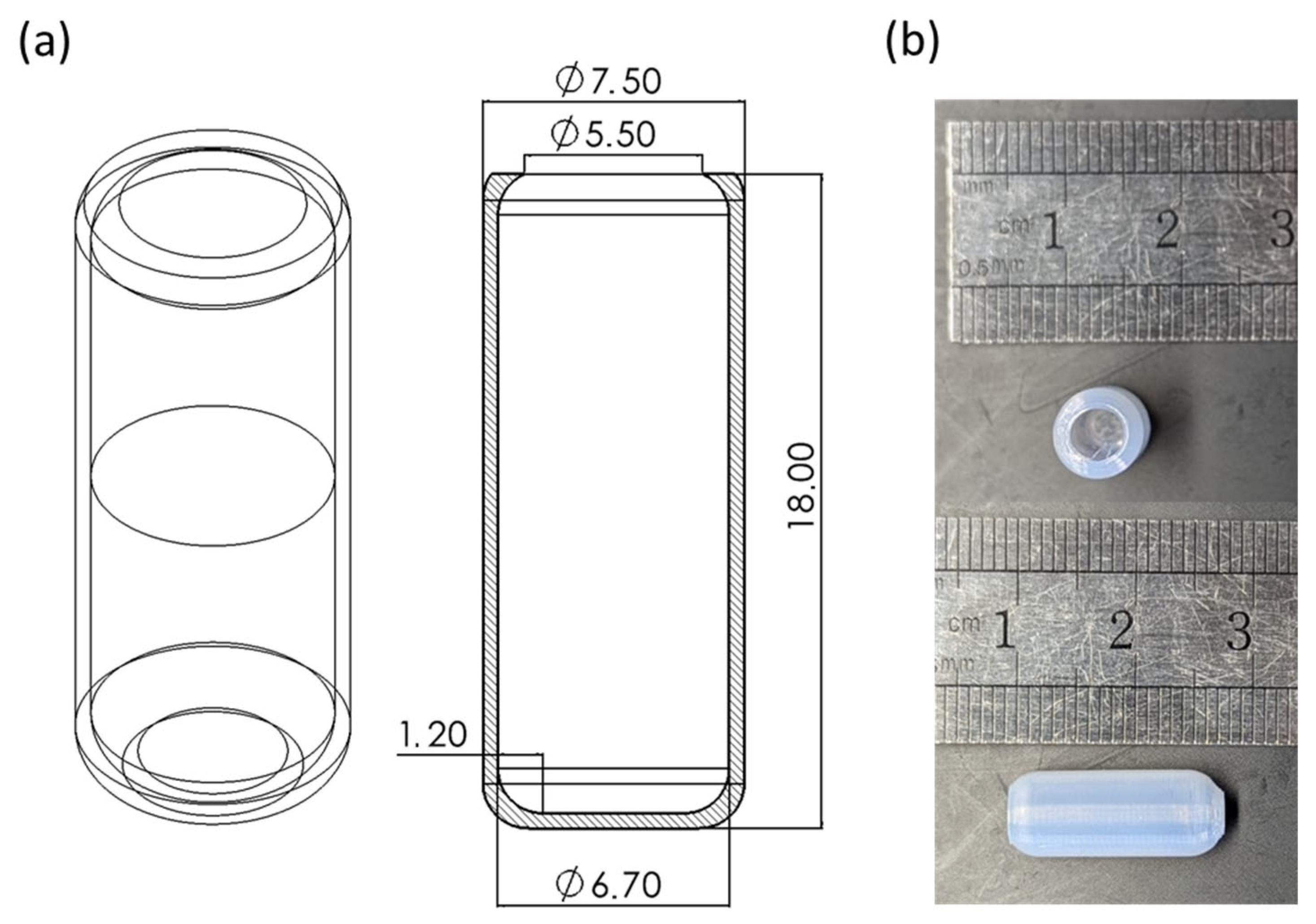

3.2. Hollow Capsule Fabrication

3.3. Morphological Characterization

3.4. Mechanical Characterization of Hollow Capsule

3.5. Oil Encapsulation with and Without Xanthan Gum

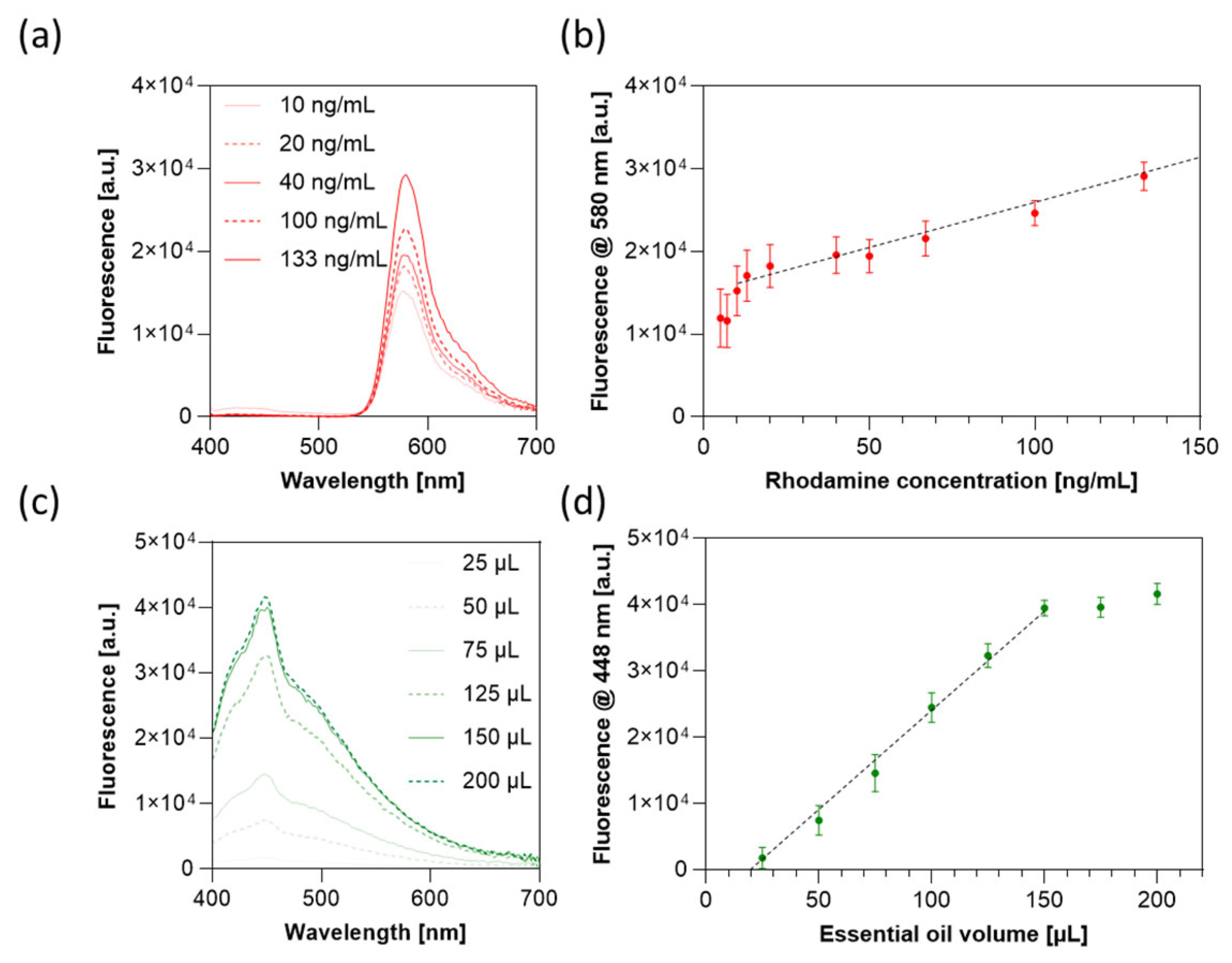

3.6. Drug Release Profile

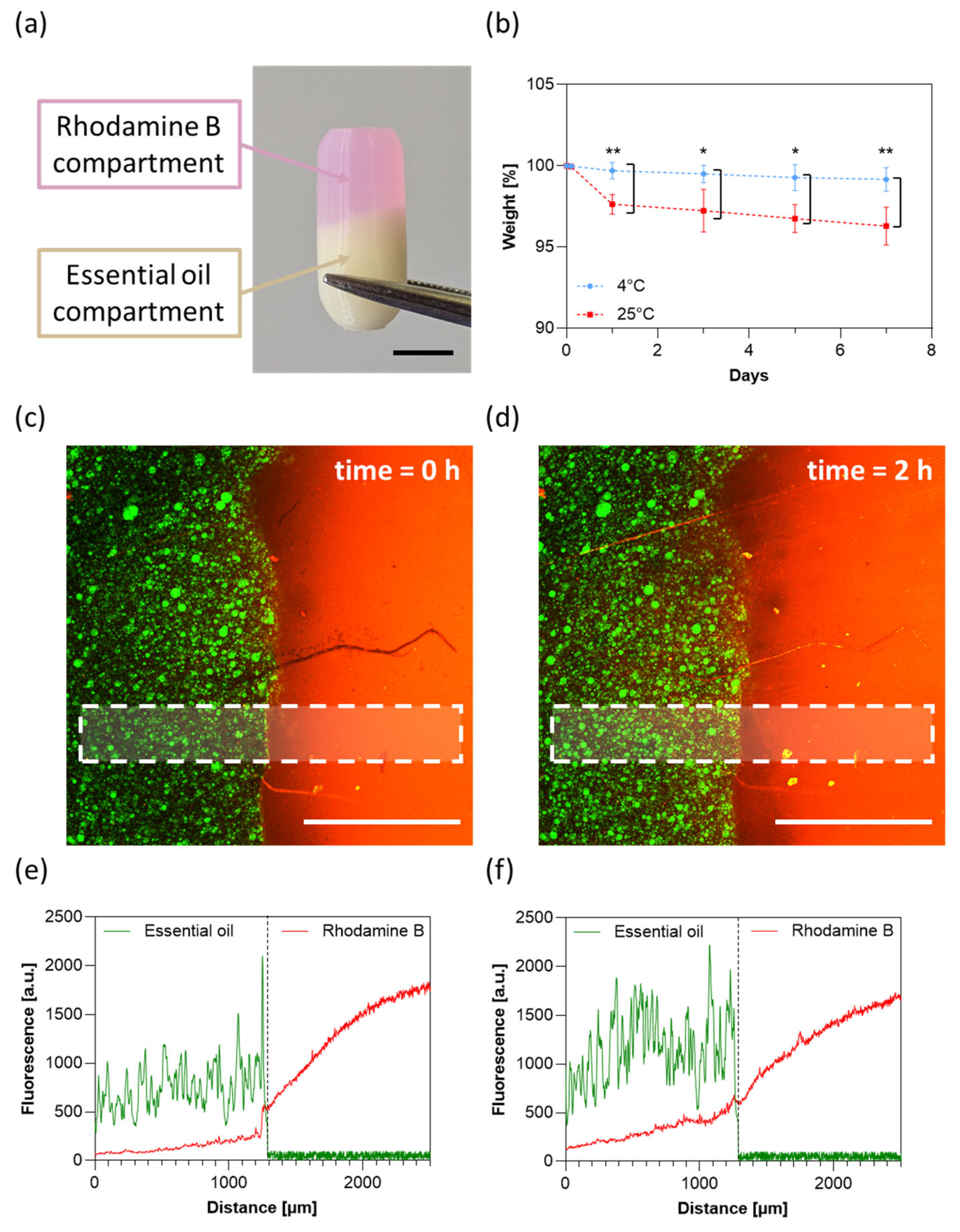

3.7. Capsule Stability and Inter-Compartmental Cross-Contamination

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bácskay, I.; Ujhelyi, Z.; Fehér, P.; Arany, P. The Evolution of the 3D-Printed Drug Delivery Systems: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni, A.; Melocchi, A.; Parietti, F.; Foppoli, A.; Zema, L.; Gazzaniga, A. 3D printed multi-compartment capsular devices for two-pulse oral drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 268, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, D.U.; Pareek, A.; Uniyal, P.; Prajapati, B.G.; Thanawuth, K.; Sriamornsak, P. Innovative applications of 3D printing in personalized medicine and complex drug delivery systems. iScience 2025, 28, 113505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Murty, U.S.; Banerjee, S. 3D printing and enteric coating of a hollow capsular device with controlled drug release characteristics prepared using extruded Eudragit® filaments. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2021, 26, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chansatidkosol, S.; Limmatvapirat, C.; Sriamornsak, P.; Akkaramongkolporn, P.; Thanawuth, K.; Krongrawa, W.; Limmatvapirat, S. 3D-Printed Shellac-Based Delivery Systems: A Biopolymer Platform for Intestinal Targeting of Biologically Active Compounds. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 48551–48562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlenfeld, C.; Duffy, P.; Yang, F.; Pérez, D.Z.; El-Saleh, F.; Durig, T. Excipients in Pharmaceutical Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Exploration of Polymeric Material Selection for Enhanced 3D Printing. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzhrani, R.F.; Fitaihi, R.A.; Majrashi, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Maniruzzaman, M. Toward a harmonized regulatory framework for 3D-printed pharmaceutical products: The role of critical feedstock materials and process parameters. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 4501–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaie, F.; Ferrero, C.; Caraballo, I. Development of 3D-Printed Bicompartmental Devices by Dual-Nozzle Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) for Colon-Specific Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Han, X.; Hong, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, A. A Review of 3D Printing Technology in Pharmaceutics: Technology and Applications, Now and Future. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh-Bey-Kinj, Z.; Heller, Y.; Socratous, G.; Christodoulou, P. 3D Printing in Oral Drug Delivery: Technologies, Clinical Applications and Future Perspectives in Precision Medicine. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.J.; Choi, H.J.; Moon, S.J.; Kim, S.J.; Bajracharya, R.; Min, J.Y.; Han, H.-K. Pharmaceutical applications of 3D printing technology: Current understanding and future perspectives. J. Pharm. Investig. 2018, 49, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wan, J.; Xi, J.; Shi, W.; Qian, H. AI-driven design of customized 3D-printed multi-layer capsules with controlled drug release profiles for personalized medicine. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 656, 124114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Huang, S.; Tran, H. Development of 3D-Printed Two-Compartment Capsular Devices for Pulsatile Release of Peptide and Permeation Enhancer. Pharm. Res. 2024, 41, 2259–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, M.S.; Ahmad, J.; Mohammed, A.A.; Ahmad, M.Z. Extrusion-based 3D printing for development of complex capsular systems for advanced drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 663, 124550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Salehi, Z.; Akrami, M.; Hosseinpour, M.; Jockenhövel, S.; Ghazanfari, S. 3D printed pH-responsive tablets containing N-acetylglucosamine-loaded methylcellulose hydrogel for colon drug delivery applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 645, 123366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, E.; O’sHea, J.P.; Griffin, B.T.; Dumont, C.; Jannin, V. Next generation capsules: Emerging technologies in capsule fabrication and targeted oral drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 214, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salawi, A. Pharmaceutical Coating and Its Different Approaches, a Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantaros, A.; Ganetsos, T.; Petrescu, F.I.T.; Ungureanu, L.M.; Munteanu, I.S. Post-Production Finishing Processes Utilized in 3D Printing Technologies. Processes 2024, 12, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbe, N.B.; McCarron, P.A.; Lane, M.E.; Tambuwala, M.M. Application of three-dimensional printing for colon targeted drug delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2017, 7, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melocchi, A.; Parietti, F.; Maccagnan, S.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Antenucci, S.; Briatico-Vangosa, F.; Maroni, A.; Gazzaniga, A.; Zema, L. Industrial Development of a 3D-Printed Nutraceutical Delivery Platform in the Form of a Multicompartment HPC Capsule. Aaps Pharmscitech 2018, 19, 3343–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J.; Ma, L.; Zou, L.; Liu, W. Shell–Core Microbeads Loaded with Probiotics: Influence of Lipid Melting Point on Probiotic Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendel, U. Assessing Viability and Stress Tolerance of Probiotics—A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 818468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak-Skierska, J.; Ludwiczak, A.; Sibińska, E.; Pomastowski, P. Environmental Influence on Bacterial Lipid Composition: Insights from Pathogenic and Probiotic Strains. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 37789–37801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryńska, A.; Carayon, I.; Kosmela, P.; Szeliski, K.; Łapiński, M.; Pokrywczyńska, M.; Kucińska-Lipka, J.; Janik, H. A comprehensive evaluation of flexible FDM/FFF 3D printing filament as a potential material in medical application. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 138, 109958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Size, Shape, and Other Physical Attributes of Generic Tablets and Capsules Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2015.

- European Union. EMA/CHMP/QWP/805880/2012 Rev. 2, Guideline on pharmaceutical development of medicines for paediatric use, European Medicines Agency, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, C.G.; Hendren, R.; Schindler, A.; Woodward, S.C. The enzymatic surface erosion of aliphatic polyesters. J. Control. Release 1984, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, R.; Yildirim, E.; Pasquinelli, M.A.; King, M.W. Hydrolytic Degradation of Polylactic Acid Fibers as a Function of pH and Exposure Time. Molecules 2021, 26, 7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, M.D.; Eyiler, E.; Walters, K.B. Hydrolytic degradation of bio-based polyesters: Effect of pH and time. Polym. Test. 2016, 52, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, L.N.; Grunlan, M.A. Hydrolytic Degradation and Erosion of Polyester Biomaterials. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minopoli, A.; Evangelista, D.; Marras, M.; Perini, G.; Palmieri, V.; De Spirito, M.; Papi, M. Viscoelastic interpretation of AFM nanoindentation for predicting nanoscale stiffness in soft biomaterials. Polym. Test. 2025, 153, 109026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducray, F.; Ramirez, C.; Robert, M.; Fontanilles, M.; Bronnimann, C.; Chinot, O.; Estrade, F.; Durando, X.; Cartalat, S.; Bastid, J.; et al. A Multicenter Randomized Bioequivalence Study of a Novel Ready-to-Use Temozolomide Oral Suspension vs. Temozolomide Capsules. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Perez, E.; Santos-Vizcaino, E.; Goyanes, A.; Basit, A.W.; Hernandez, R.M. 3D-Printed core-shell tablet for effective oral delivery of AT-MSC secretome in inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minopoli, A.; Perini, G.; Evangelista, D.; Marras, M.; Augello, A.; Palmieri, V.; De Spirito, M.; Papi, M. 3D-Printed Multifunctional Multicompartment Polymer-Based Capsules for Tunable and Spatially Controlled Drug Release. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120456

Minopoli A, Perini G, Evangelista D, Marras M, Augello A, Palmieri V, De Spirito M, Papi M. 3D-Printed Multifunctional Multicompartment Polymer-Based Capsules for Tunable and Spatially Controlled Drug Release. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2025; 16(12):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120456

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinopoli, Antonio, Giordano Perini, Davide Evangelista, Matteo Marras, Alberto Augello, Valentina Palmieri, Marco De Spirito, and Massimiliano Papi. 2025. "3D-Printed Multifunctional Multicompartment Polymer-Based Capsules for Tunable and Spatially Controlled Drug Release" Journal of Functional Biomaterials 16, no. 12: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120456

APA StyleMinopoli, A., Perini, G., Evangelista, D., Marras, M., Augello, A., Palmieri, V., De Spirito, M., & Papi, M. (2025). 3D-Printed Multifunctional Multicompartment Polymer-Based Capsules for Tunable and Spatially Controlled Drug Release. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 16(12), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb16120456