Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the influence of a nanohydroxyapatite layer applied to the surface of titanium or titanium alloy implants on the intricate process of osseointegration and its effect on osteoblast cell lines, compared to uncoated implants. Additionally, the investigation scrutinizes various modifications of the coating and their consequential effects on bone and cell line biocompatibility. On the specific date of November 2023, an exhaustive electronic search was conducted in esteemed databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus, utilizing the meticulously chosen keywords ((titanium) AND ((osteoblasts) and hydroxyapatite)). Methodologically, the systematic review meticulously adhered to the PRISMA protocol. Initially, a total of 1739 studies underwent scrutiny, with the elimination of 741 duplicate records. A further 972 articles were excluded on account of their incongruence with the predefined subjects. The ultimate compilation embraced 26 studies, with a predominant focus on the effects of nanohydroxyapatite coating in isolation. However, a subset of nine papers delved into the nuanced realm of its modifiers, encompassing materials such as chitosan, collagen, silver particles, or gelatine. Across many of the selected studies, the application of nanohydroxyapatite coating exhibited a proclivity to enhance the osseointegration process. The modifications thereof showcased a positive influence on cell lines, manifesting in increased cellular spread or the attenuation of bacterial activity. In clinical applications, this augmentation potentially translates into heightened implant stability, thereby amplifying the overall procedural success rate. This, in turn, renders nanohydroxyapatite-coated implants a viable and potentially advantageous option in clinical scenarios where non-modified implants may not suffice.

1. Introduction

Titanium and its alloys play a crucial role in medical and dental applications, particularly in the creation of orthopaedic and dental implants [1]. Recognized for its outstanding biocompatibility, which promotes strong cell attachment, high mechanical strength, and corrosion resistance, titanium stands out as a material with exceptional properties [1,2,3], hence its widespread adoption in contemporary dentistry. Dental titanium has emerged as the preferred material for applications such as dental implants, consistently demonstrating high success rates over the years. In recent decades, there has been a surge in the development of various methods to modify the surface of titanium dental implants, aiming to enhance both its physical and chemical characteristics. This pursuit is driven by the desire to improve patient comfort, reduce healing periods, and achieve more predictable treatment outcomes [4]. Despite titanium’s inherent excellence, surface modifications offer the potential to further elevate treatment results. Techniques such as roughening, air abrasion, acid etching, titanium plasma spray (TPS), micro-arc oxidation (MAO), and steam–hydrothermal treatment (SHT) are among the methods employed for surface functionalization. Titanium plasma spray (TPS) stands out as a commonly used approach [1]. Notably, additive manufacturing (AM) holds significant promise, allowing for the replication of natural cancellous bone structure [2]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that while dental implants serve as an excellent solution for replacing missing teeth, they do not offer a lifelong guarantee. Both the practitioner and the patient must remain vigilant to the possibility of early and late implant failures. Assuming a correctly planned and executed implantation process, early failures commonly result from issues such as improper osseointegration and peri-implantitis. Conversely, late implant failures may be attributed to systemic diseases, infections, radiotherapy, unhealthy habits such as smoking or alcoholism, overloading, traumatic occlusion, parafunctional habits, or psychological factors. It is important to emphasize that dental implants are non-resorbable applications, signifying that once anchored in the cortical bone, they are intended to osseointegrate with the surrounding bone, requiring another surgical procedure for removal.

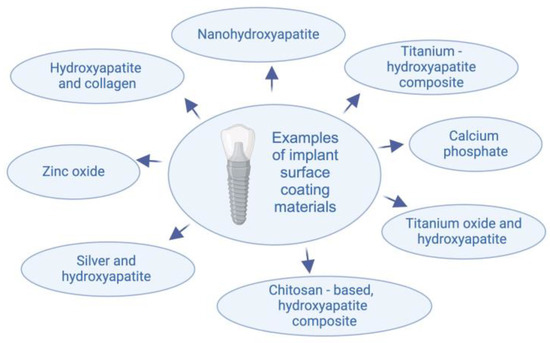

Among other techniques, coating offers durable and uniform protection, versatility, and cost-effectiveness for large-scale applications, making it suitable for various surfaces. The surface of titanium implants modified by sandblasting, laser processing, and acid etching (SLA surface) is considered the gold standard for preparing implants with high osteointegration potential [3]. The choice of the implant with or without coating depends on specific local factors (such as bone quality) and general factors (such as systemic health) of the patients. In the context of the reviewed article, a nanohydroxyapatite-based coating introduces the desired bioactivity affecting osteoblast differentiation, whereas laser processing or acid etching may not achieve the same goal [3]. The application of coatings on titanium implant surfaces has shown significant potential in enhancing the osseointegration process [5]. This improvement is attributed to the augmented proliferation, differentiation, and mineralization of osteoblasts [6]. Additionally, the accelerated processes of osteogenesis and angiogenesis contribute to a notable reduction in the risk of implant failure [6]. Various coating materials have been explored for their effectiveness in improving the properties of titanium implants. For instance, hydroxyapatite alone has demonstrated positive outcomes, and its combinations with other materials such as silver, chitosan, calcium phosphate, zinc oxide, and collagen have been investigated [1,2]. Application of silver/hydroxyapatite nanoparticle coating has a promising potential to elevate the biocompatibility of dental implants due to the absence of cytotoxic effects, as well as to reduce inflammatory responses after implantation. The combination of nanohydroxyapatite with chitosan revealed a promotion of osteoblast adhesion and differentiation, associated with the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells. By calcium phosphate coating, a modification of surface topography and subsequent enhancement of osteoblast proliferation can be obtained. Zinc oxide nanoparticles coating manifest a potent antibacterial effect against Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis. Collagen incorporation into the hydroxyapatite coating positively influences cell spreading.

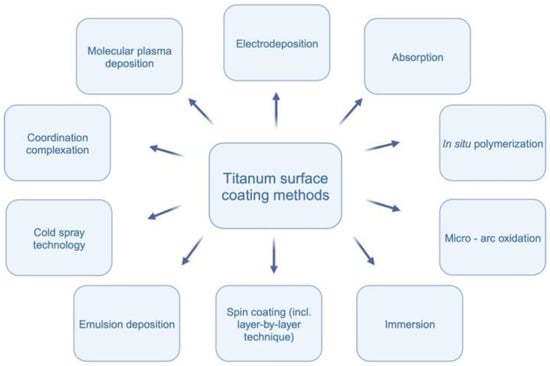

The incorporation of these materials aims to optimize the surface characteristics of titanium implants, providing better outcomes in terms of patient comfort, shorter healing periods, and predictable treatment results (see Figure 1) It is worth mentioning that as an alternative to hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite can be used as coating for titanium [7]. Due to differences in structure and properties, using fluorapatite can be a subject of a separate systematic review [8].

Figure 1.

Titanium surface coating methods.

The application of hydroxyapatite in nanoparticle form demonstrates promising potential for enhancing cell proliferation and improving the osseointegration process on titanium surfaces [9,10,11]. Various techniques for coating titanium surfaces exist, including molecular plasma deposition, electrodeposition, micro-arc oxidation, in situ polymerization, immersion, emulsion deposition, cold spray technology, and spin coating [2,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Molecular plasma deposition allows precise control over coating thickness, while electrodeposition is cost-effective with good thickness control [12]. Micro-arc oxidation results in a ceramic-like coating, and in situ polymerization enables the incorporation of specific functionalities [16]. Immersion is a simple and cost-effective method, and emulsion deposition provides good coverage with the incorporation of multiple components [9]. Cold spray technology produces dense coatings without high-temperature exposure, and spin coating achieves even coatings through centrifugal force [2]. Each method has unique advantages and challenges, and the choice depends on the desired coating characteristics. Figure 2 visually represents the methodologies employed in the reviewed studies.

Figure 2.

Materials used for implant surface coating.

Osteoblasts, as primary contributors to the osseointegration process, are integral for orchestrating new bone formation and remodeling [5,6]. Their pivotal role extends to fostering the crucial aspect of achieving robust primary and secondary stability in dental implants, which is paramount for successful healing and treatment outcomes [1,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. The timeframe between the second and fourth weeks post-implant placement is particularly critical, given that this period is characterized by predominant bone remodeling in cortical bone, while mineralization in cancellous bone is not yet fully established [3]. The strategic functionalization of titanium implant surfaces holds tremendous potential, as it can effectively expedite the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts, thereby significantly accelerating the overall osseointegration process [10]. This not only enhances the prospects for achieving accelerated and robust implant stability but also serves as a promising strategy to mitigate the risk of early implant failure [9,10].

In this investigation, our primary aim was to assess the impact of nanohydroxyapatite as a coating material on implant surface functionalization and its subsequent effects on implant properties. Through a rigorous article selection process, adhering to predefined eligibility criteria, we systematically reviewed and synthesized data to identify optimal strategies for modifying implant surfaces. It is important to note that, as of now, a comprehensive systematic review addressing this specific topic is lacking in the existing literature. The completion of such a review not only contributes essential insights but also serves as a potential stimulus for researchers to undertake additional studies. This, in turn, holds the promise of delivering substantial advancements for both implantologists/surgeons and patients in the foreseeable future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question

This systematic review adhered to the PICO framework with the following components.

PICO question: In the context of titanium implants (population), does the application of a nanohydroxyapatite layer to its surface (investigated condition) influence the osseointegration process and impact osteoblasts (outcome), as compared to conventional implants without surface functionalization (comparison condition)?

2.2. Protocol

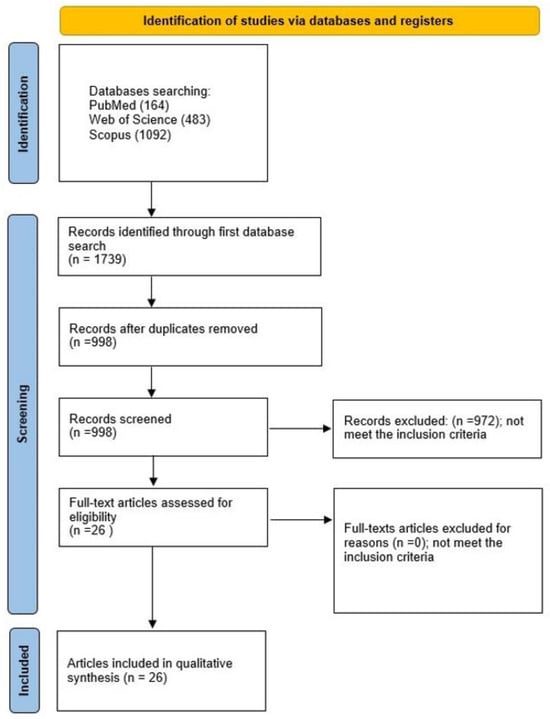

The selection process for articles in the systematic review was carefully outlined following the PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

All studies included in the systematic review had to meet specific criteria, including: the investigation of nanohydroxyapatite-coated titanium, examination of the impact of nanohydroxyapatite-covered titanium on osteoblasts, inclusion of both in vitro and in vivo studies, involvement of animal and human specimens, and publication in the English language. The reviewers collectively established exclusion criteria, which included studies in non-English languages, clinical reports, opinions, editorial papers, review articles, and studies lacking a full-text version.

2.4. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

In November 2023, the authors conducted a search in electronic databases, including Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science. The authors restricted the results in PubMed and Web of Science to titles and abstracts. In the Scopus database, the search results were limited to keywords, titles, and abstracts. The search criteria were carefully formulated using the keywords ((titanium) AND ((osteoblasts) and hydroxyapatite)). The searches strictly adhered to the established eligibility criteria. After screening abstracts and subsequently reviewing complete full-text versions of articles, only studies related to the utilization of nanohydroxyapatite were included.

2.5. Data Collection and Data Items

Six reviewers (K.H., W.Z., P.J.P, A.P., J.K., W.D.) carefully selected articles that met the pre-established criteria. Then, the aforementioned authors collected essential data and organized it in a standardized Excel file.

2.6. Assessing Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

During the initial stage of study selection, the authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of each study to minimize potential reviewer bias. The level of agreement among reviewers was determined using Cohen’s κ test. Any differences of opinion on the inclusion or exclusion of a study were resolved through discussion between the authors. Risk of bias was assessed based on the quality assessment.

2.7. Quality Assessment

Two independent evaluators (W.Z., J.M.) systematically appraised the procedural quality of each study within the article. The assessment criteria were meticulously designed to focus on critical information pertaining to the nanhydroxyapatite coating on titanium implants. In evaluating study design, implementation, and analysis, rigorous criteria were applied, including a stipulated minimum group size of 10 subjects, the inclusion of a control group, thorough sample size calculation, a precise description of the procedural technique and comprehensive manufacturer’s data, clarification of osteoblast incubation time, and specification of the osteoblasts line used. The studies underwent scoring on a calibrated scale ranging from 0 to 6 points, where a higher score denoted superior study quality. The evaluation of risk of bias followed a meticulous scoring system: 0–2 points indicating a high risk, 3–4 points denoting a moderate risk, and 5–6 points indicating a low risk. Any disparities in scoring were meticulously addressed through thorough discussion until a consensus was achieved.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

A comprehensive evaluation initiated with a total of 1739 studies, from which 741 duplicates were systematically removed. Scrutiny of titles and abstracts resulted in the exclusion of 972 articles that did not align with the specified subjects or objectives. Further refinement during the full-text examination confirmed the inclusion of all papers identified during the initial abstract screening. The final selection for qualitative synthesis comprised 26 studies [1,2,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], all written in English, and focused on the in vitro assessment of the impact of nanohydroxyapatite-coated titanium on osteoblast activity.

3.2. General Characteristics of the Included Studies

The primary objective of this comprehensive systematic review was to meticulously evaluate the implications of implant surface functionalization on the intricate process of osseointegration and its nuanced impact on osteoblast behaviour. The prevalent consensus derived from a substantial body of literature [5,6,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30,31] consistently underscores the pivotal role played by implant surface functionalization in augmenting the osseointegration phenomenon. It is imperative to highlight, however, that a singular study conducted by MacBard et al. [2] posited that the application of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coating on diverse titanium surfaces might confer limited advantages in cultivating an osteogenic microenvironment. Several investigations [5,6,24,25,26,27,28,29] have directed their focus predominantly towards surface topography and porosity, foregrounding these aspects over the intrinsic properties of coatings. Fernandes et al.’s [5] study distinctly delineated how surface topography significantly modulates osteoblast metabolic activities. Insights gleaned from the investigations by Pourmollaabbassi et al. [6] and Man et al. [29] unveiled that distinct pore sizes and shapes on titanium implant surfaces elicit varied effects on functionalization. Notably, higher porosity and larger pore sizes within HA/TiO2 coatings were observed to be conducive to the migration and proliferation of osteoblasts [6]. Furthermore, the shape of the pores emerged as a critical factor; for instance, the triangular pore configuration exhibited a marked enhancement in osteoblast mineralization [29].

A significant corpus of the scientific literature [1,11,12,13,14,16,19,20,21,25,26,30] is dedicated to the meticulous exploration of titanium surface coating with hydroxyapatite in nanoparticulate form and its consequential impact on material properties. The prevailing consensus derived from these studies consistently substantiates that the application of nanohydroxyapatite coating markedly enhances osteogenic properties. In several investigations [9,10,15,16,17,18,20,22,25,27,31], the incorporation of supplementary materials into the hydroxyapatite coating framework has been explored. Chien et al. [15] conducted a study on the dopamine-assisted deposition of hydroxyapatite coating on a titanium substrate, resulting in improved osteoconductivity. Similarly, Kreller et al. [18] treated a titanium surface with a biomimetic calcium phosphate coating, leading to modified surface topography and enhanced osteoblast proliferation. Zhu and colleagues (2010) presented empirical evidence demonstrating that the inclusion of collagen in the hydroxyapatite coating has a positive effect on cell spreading. Two noteworthy studies by Chen et al. [25] and Ma et al. [31] underscored the synergistic osteogenic effects achieved through the combination of nanohydroxyapatite and chitosan. Specifically, Chen et al. [25] scrutinized a structure composed of chitosan-catechol, gelatine, and hydroxyapatite nanofibers, unveiling a promotion of osteoblast adhesion and differentiation, coupled with the proliferation of mesenchymal stem cells.

Ma et al. [31] contribute additional empirical support, affirming the constructive influence exerted by the nanohydroxyapatite/chitosan composite coating on the facilitation of the osseointegration process. According to Qiaoxia et al. [9], the hydroxyapatite coating has heightened antioxidant properties that are critical for reducing reactive oxygen species at the bone–implant interface. The hydroxyapatite/tannic coating, which is characterized by its antioxidant attributes, plays a pivotal role in ameliorating oxidative stress at the bone–implant interface. In two supplementary investigations, Salaie et al. [10] and Fathy Abo-Elmahasen et al. [27], researchers delve into the application of silver/hydroxyapatite nanoparticle coating. Salaie et al. [10] specifically validate the absence of cytotoxic effects, underscoring the potential of silver/hydroxyapatite coating to elevate the biocompatibility of dental implants. Simultaneously, Fathy Abo-Elmahasen et al. [27] unveil a pronounced reduction in bacterial colonies, shedding light on antibacterial properties and proposing the potential of nanocoating as a strategic approach to mitigate inflammatory responses around dental implants (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Presents the general characteristics, including the aim of the study, methods and materials employed, results obtained, and conclusions drawn for each research.

3.3. Main Study Outcomes

Twenty-five studies [5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] collectively provide robust support for the hypothesis that nanohydroxyapatite coating significantly improves the chemo-mechanical properties of titanium implant surfaces. This augmentation is intricately linked to increased levels of adhesion, cell proliferation, and osteoblast differentiation, thereby accelerating the complex process of osteogenesis. However, a single study by MacBard et al. [2] departs from this prevailing consensus and suggests that nanohydroxyapatite coating on titanium surfaces may have no discernible effect on osteogenic properties. Within the corpus of these studies, nine [6,12,13,15,18,20,21,24,25] specifically reported the promotion of osteoblast proliferation, while five [1,11,13,17,31] underscored the heightened differentiation of osteoblasts. Six studies [14,15,25,26,28,31] demonstrated an increase in osteoblast adhesion. Notable findings from individual studies include a study [9] confirming that hydroxyapatite coating promotes antioxidant properties and another [27] claiming that hydroxyapatite/silver coating has antimicrobial activity. In addition, three studies [16,19,25] concluded that hydroxyapatite stimulates not only osteogenesis but also angiogenesis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Detailed characteristics of included studies.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Assessing the risk of bias is essential for ensuring transparency in the synthesis of evidence and the communication of results and findings. The evaluation of study quality, which involves identifying and addressing design flaws, serves as a crucial method for determining the reliability of the studies under consideration. In this scientific endeavor, the authors employed a rigorous approach to assess the quality of the research papers, employing carefully chosen criteria measured on a scale of 0–1, as outlined in Table 3. These criteria encompassed key factors such as group size (at least 10 subjects), presence of a control group, sample size calculation, detailed description of procedure, inclusion of manufacturer’s data, specification of the type of osteoblast line, osteoblast time incubation, and a comprehensive summary of the aforementioned points, forming the basis for calculating the risk of bias. Each criterion present in the assessed scientific work was denoted as ‘1’ in Table 3, while its absence was marked as ‘0’. All the studies were considered to have a moderate risk of bias, with a score of 3/6 [1,2,18,21,25,26,27] and 4/6 [5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,22,23,24,28,29,30,31]. A “High risk” rating indicates significant bias that may invalidate the results, on the other hand, “low risk” is considered as a limited amount of bias that could influence the final quality of the research (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Assessing risk of bias, presence (1) or its absence (0).

4. Discussion

As individuals undergo the aging process, the inevitable occurrence of permanent tooth loss becomes apparent. The etiological factors contributing to this phenomenon include periodontal diseases, traumatic incidents such as falls or sports injuries, improper root canal treatments, the absence of permanent tooth buds, and congenital or developmental abnormalities [32,33]. In addressing the restoration of missing teeth, dental implants, as elucidated in reference [16], assume a pivotal role. Conventional dental implants employed for such purposes are fabricated from titanium and its alloys [34]. The strategic utilization of titanium and its derivatives is predicated on their capacity to ensure biocompatibility, corrosion resistance, commendable physical properties, and an effective interaction with body cells, facilitating their adhesion to the implant surface [35,36]. Dentistry, as an ever-evolving scientific discipline, steadfastly pursues the advancement of dental materials and treatment outcomes [37]. Global research endeavours in dental materials, inclusive of implants, are underway to augment their intrinsic characteristics. The present study is poised to scrutinize the nuanced impact of implant surface functionalization on the intricate process of osseointegration. A comprehensive review of the pertinent literature within our investigation consistently underscores the proposition that the deliberate functionalization of the implant surface exerts a direct and substantive influence on the osseointegration process.

Many studies indicated that sandblasting titanium with nanohydroxyapatite alters the surface structure, affecting pre-osteoblasts and directing osteoblast metabolism [5,38,39]. This process creates a roughened surface with increased surface area, which can enhance the osseointegration of the implant. In a separate experiment, titanium-coated HAp nanotubes were produced as an implant coating. The experimental surface exhibited increased osteoblast adhesion and a strong antioxidant effect, with significant potential for ROS removal at the bone–implant interface [9]. After implantation, the surrounding area may experience oxidative stress and bacterial infections, which can lead to apoptosis and eventual bone resorption and implant failure. Free reactive oxygen species are crucial factors contributing to implant loss, owing to the fact that they favour bone resorption. By synergistic antioxidant action of hydroxyapatite and antimicrobial activity of materials like silver or zinc oxide, it is possible to reduce the risk of peri-implantitis development and, in consequence, implant loss [40]. The antioxidant properties of hydroxyapatite were also found by the authors who additionally enriched this material with catechin [41]. It seems that such a modification may have a promising effect, improve the effectiveness of treatment, and prevent the occurrence of peri-implantitis. In one of the experiments, a nanocomposite scaffold was created using Polyurethane sponge, with 50% of its weight being HAp and TiO2. The scaffold was used for architectural modeling. The study demonstrated that the P3HB-coated polyurethane sponge possesses mechanical strength and an architecture that is appropriate for osteoblast seeding and growth [9].

To enhance biocompatibility, cell proliferation, and osseointegration, it may be crucial to create suitable architectural structures [6]. Porous surfaces provide more surface area for bone cells to attach and proliferate, which is essential for osseointegration [4]. This is because bone cells can more easily spread out and interact with the implant surface when there are more pores. Other researchers also confirm that pore size influences osteogenesis [42]. Some studies have demonstrated that surface topography significantly affects osteoblast metabolism [43,44]. Moreover, the shape of the pores is also important [29,42,45,46]. The study revealed that implants featuring larger pores, higher interconnectivity, and interconnected macropores demonstrated superior osseointegration when compared to implants with smaller pores, lower interconnectivity, and non-interconnected macropores [47]. Researchers have demonstrated that implants featuring irregular and interconnected pore shapes generally facilitate superior bone formation and osseointegration when compared to implants with smooth or closed-end pores [48].

Some researchers indicate the possibility of incorporating biologically active compounds such as dopamine or calcium phosphate into coatings. This provides titanium implants the biomimetic properties [15,18,49,50,51]. Dopamine forms a self-assembling polydopamine (PDA) layer on titanium surfaces. This layer provides more surface area for bone cells to attach, enhancing their ability to spread and proliferate. PDA carries a negative charge, which aids in cell adhesion and migration. Moreover, it is like the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is the natural scaffold of bone tissue [52,53]. CaP coatings provide an osteoconductive environment for cell attachment, differentiation, and proliferation. CaP coatings facilitate ion exchange between the implant and surrounding bone tissue, promoting the osteointegration process. The release of Ca2+ and PO43- ions from CaP coatings stimulates osteoblast differentiation [54,55].

Analysis of the data contained in the publications showed that multidirectional surface functionalization of titanium alloys is highly desirable in contemporary regenerative medicine. Nanohydroxyapatite coatings are totally biocompatible implant elements that aid in improving osseointegration processes. They do not cause adverse reactions or inflammation, creating a favourable environment for bone cells to adhere, grow, and differentiate. Due to the diversity of the research methodology used, the possibility of comparing different functionalization methods is limited. The main limitation of this systematic review is that the samples studied were not kept under the same standardized conditions, because the selected studies were based on both in vitro and in vivo examinations of samples. Establishing standardized protocols for coating preparation, implant fabrication, and evaluation methods would enable more rigorous comparisons of different functionalization approaches. Functionalization of implant surfaces is an interesting research direction and certainly requires further research, including evaluation in clinical conditions.

5. Conclusions

Many of the studies assessed in this scientific endeavour affirm that the functionalization of titanium implant surfaces using nanohydroxyapatite enhances osteogenic abilities and expedites the osseointegration process. It is noteworthy that not only does the nanohydroxyapatite coating in isolation impact the overall osseointegration process, but its modifications, such as combining it with materials like collagen, calcium phosphate, or chitosan, can also exert influence. The examined scientific work reveals that modified hydroxyapatite coating additionally augments cell line proliferation, osteogenic activity, or cell spreading, thereby accelerating the entire implantation process. Hence, considering additional modifications to the implant surface becomes imperative, as it contributes to establishing a conducive environment within the tissues upon the modified implant’s contact with the bone. This systematic review, based on the selected studies, unequivocally asserts that hydroxyapatite, whether in its pristine form or modified, especially in the form of nanoparticles, possesses the ability to promote osteoblast adhesion and proliferation. Furthermore, it facilitates their mineralization and ultimately enhances both osteogenesis and angiogenesis processes. The anticipation is that the application of nanomaterials in dentistry, particularly in surgery, will continue to burgeon. The trajectory of medicine stands to gain substantially from the ongoing research on nanomaterials in dental surgery.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the final article: conceptualization, M.D. and R.J.W.; methodology, K.H. and W.Z.; software, A.P. and W.D.; validation, K.H. and J.M.; investigation, K.H., W.Z., P.J.P., A.P. and W.D.; data curation, K.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H., W.Z., W.D, P.J.P., A.P. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M., M.D. and R.J.W.; supervision, J.M., M.D. and R.J.W.; project administration, M.D. and R.J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a subsidy from Wroclaw Medical University, number SUBZ.B180.24.058.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Science Centre Poland (NCN) for financial support within the Project ‘Biocompatible materials with theranostics’ properties for precision medical application (No. UMO-2021/43/B/ST5/02960).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Wu, H.; Chen, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, P. Mechanical and Biological Properties of Titanium and Its Alloys for Oral Implant with Preparation Techniques: A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBarb, R.F.; Lindsey, D.P.; Bahney, C.S.; Woods, S.A.; Wolfe, M.L.; Yerby, S.A. Fortifying the Bone-Implant Interface Part 1: An In Vitro Evaluation of 3D-Printed and TPS Porous Surfaces. Int. J. Spine Surg. 2017, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, H.F.; Ochi, S. Hydroxyapatite-coated implants: A case for their use. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 56, 1303–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Świder, K.; Flieger, R.; Dominiak, M. Assessment of the primary stability of root analog zirconia implants designed using cone beam computed tomography software by means of the Periotest® device: An ex vivo study. A preliminary report. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.J.C.; Bezerra, F.; Ferreira, M.R.; Andrade, A.F.C.; Pinto, T.S.; Zambuzzi, W.F. Nano hydroxyapatite-blasted titanium surface creates a biointerface able to govern Src-dependent osteoblast metabolism as prerequisite to ECM remodeling. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 163, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmollaabbassi, B.; Karbasi, S.; Hashemibeni, B. Evaluate the growth and adhesion of osteoblast cells on nanocomposite scaffold of hydroxyapatite/titania coated with poly hydroxybutyrate. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2016, 5, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chao, Y.; Wan, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, H. Fluoridated hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium obtained by electrochemical deposition. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedali Seyedmajidi, M.S. Fluorapatite: A Review of Synthesis, Properties and Medical Applications vs Hydroxyapatite. Iran. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liam, X.; Chen, W.; Huang, D. Hydroxyapatite/tannic acid composite coating formation based on Ti modified by TiO2 nanotubes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 196, 111304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaie, R.N.; Besinis, A.; Le, H.; Tredwin, C.; Handy, R.D. The biocompatibility of silver and nanohydroxyapatite coatings on titanium dental implants with human primary osteoblast cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 107, 110210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, J.H.d.L.; Matos, P.C.; de Gouvêa, C.V.D.; Carvalho, W.; Calvo-Guirado, J.L.; Aragoneses, J.M.; Pérez-Díaz, L.; Gehrke, S.A. In vitro assessment of the functional dynamics of titanium with surface coating of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Materials 2019, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, G.; Storey, D.M.; Webster, T.J. Molecular plasma deposition: Biologically inspired nanohydroxyapatite coatings on anodized nanotubular titanium for improving osteoblast density. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Dong, L.L.; He, F.; Zhao, S.; Yang, G.L. Osteoblast responses to thin nanohydroxyapatite coated on roughened titanium surfaces deposited by an electrochemical process. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 116, e311–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Rodriguez, J.; Fenniri, H.; Webster, T.J. Associate Professor of Engineering Biomimetic helical rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium for improving orthopedic implants. Int. J. Nanomed. 2008, 3, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, C.Y.; Liu, T.Y.; Kuo, W.H.; Wang, M.J.; Tsai, W.B. Dopamine-assisted immobilization of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and RGD peptides to improve the osteoconductivity of titanium. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101A, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Mei, L.; Jiang, X.; Jin, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Meng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Wu, F. Hydroxyapatite-Coated Titanium by Micro-Arc Oxidation and Steam-Hydrothermal Treatment Promotes Osseointegration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 625877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, F.; Ferreira, M.R.; Fontes, G.N.; Fernandes, C.J.d.C.; Andia, D.C.; Cruz, N.C.; da Silva, R.A.; Zambuzzi, W.F. Nano hydroxyapatite-blasted titanium surface affects pre-osteoblast morphology by modulating critical intracellular pathways. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1888–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreller, T.; Sahm, F.; Bader, R.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Jonitz-Heincke, A.; Detsch, R. Biomimetic calcium phosphate coatings for bioactivation of titanium implant surfaces: Methodological approach and in vitro evaluation of biocompatibility. Materials 2021, 14, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Du, Z.; Du, J.; Yao, W.; Zhang, J.; Weng, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. A multifaceted coating on titanium dictates osteoimmunomodulation and osteo/angio-genesis towards ameliorative osseointegration. Biomaterials 2018, 162, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, M.; Yamada, M.; Wakamura, M.; Egusa, H.; Sakurai, K. Activation of Osteoblastic Function on Titanium Surface with Titanium-Doped Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticle Coating: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2017, 32, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, M.B.; Nguyen, T.D.T.; Pitchaimani, A.; Choi, S.O.; Aryal, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite Nanoconstruct Using Chemical Gradient across Lipid Bilayer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 27382–27390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Eibl, O.; Scheideler, L.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J. Characterization of nano hydroxyapatite/collagen surfaces and cellular behaviors. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 79, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, B.; Fu, H.; Li, Y. Nano-hydroxyapatite coated TiO2 nanotubes on Ti-19Zr-10Nb-1Fe alloy promotes osteogenesis in vitro. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 207, 112019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardell, A.; Cinca, N.; Garcia-Giralt, N.; Dosta, S.; Cano, I.; Nogués, X.; Guilemany, J. Functionalized coatings by cold spray: An in vitro study of micro- and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite compared to porous titanium. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 87, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xu, K.; Tao, B.; Dai, L.; Yu, Y.; Mu, C.; Shen, X.; Hu, Y.; He, Y.; Cai, K. Multilayered coating of titanium implants promotes coupled osteogenesis and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2018, 74, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Aslani, A.; Sambito, M.A.; Kalkhoran, N.M.; Slamovich, E.B.; Webster, T.J. Nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite/titania coatings on titanium improves osteoblast adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2008, 84, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Elmahasen, M.M.F.; Dena, A.S.A.; Zhran, M.; Albohy, S.A.H. Do silver/hydroxyapatite and zinc oxide nano-coatings improve inflammation around titanium orthodontic mini-screws? In vitro study. Int. Orthod. 2023, 21, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.; Sambito, M.A.; Aslani, A.; Kalkhoran, N.M.; Slamovich, E.B.; Webster, T.J. Increased osteoblast functions on undoped and yttrium-doped nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2358–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, K.; Brunet, M.Y.; Louth, S.; Robinson, T.E.; Fernandez-Rhodes, M.; Williams, S.; Federici, A.S.; Davies, O.G.; Hoey, D.A.; Cox, S.C. Development of a Bone-Mimetic 3D Printed Ti6Al4V Scaffold to Enhance Osteoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles’ Therapeutic Efficacy for Bone Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 757220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xi, X.; Si, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Cai, K. Surface engineering of titanium alloy substrates with multilayered biomimetic hierarchical films to regulate the growth behaviors of osteoblasts. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 4525–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.-Y.; Feng, Y.-F.; Wang, T.-S.; Lei, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.-P.; Wen, X.-X.; Yu, H.-L.; Xiang, L.-B.; Wang, L. Involvement of FAK-mediated BMP-2/Smad pathway in mediating osteoblast adhesion and differentiation on nano-HA/chitosan composite coated titanium implant under diabetic conditions. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Dominiak, M. Assessment of Pain When Uncovering Implants with Er:YAG Laser or Scalpel for Second Stage Surgery. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 25, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihde, S.; Pałka, Ł.; Janeczek, M.; Kosior, P.; Kiryk, J.; Dobrzyński, M. Bite Reconstruction in the Aesthetic Zone Using One-Piece Bicortical Screw Implants. Case Rep. Dent. 2018, 2018, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, J.M.; Barão, V.A.R. Is there scientific evidence favoring the substitution of commercially pure titanium with titanium alloys for the manufacture of dental implants? Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 71, 1201–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kensy, J.; Dobrzyński, M.; Wiench, R.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Matys, J. Fibroblasts Adhesion to Laser-Modified Titanium Surfaces-A Systematic Review. Materials 2021, 14, 7305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Flieger, R.; Dominiak, M. Assessment of Temperature Rise and Time of Alveolar Ridge Splitting by Means of Er:YAG Laser, Piezosurgery, and Surgical Saw: An Ex Vivo Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 9654975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, J.; Flieger, R.; Gedrange, T.; Janowicz, K.; Kempisty, B.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Dominiak, M. Effect of 808 nm Semiconductor Laser on the Stability of Orthodontic Micro-Implants: A Split-Mouth Study. Materials 2020, 13, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.A.; da Silva Feltran, G.; Ferreira, M.R.; Wood, P.F.; Bezerra, F.; Zambuzzi, W.F. The Impact of Bioactive Surfaces in the Early Stages of Osseointegration: An In Vitro Comparative Study Evaluating the HAnano® and SLActive® Super Hydrophilic Surfaces. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3026893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczek, M.; Szymczyk, P.; Dobrzynski, M.; Parulska, O.; Szymonowicz, M.; Kuropka, P.; Rybak, Z.; Zywicka, B.; Ziolkowski, G.; Marycz, K.; et al. Influence of surface modifications of a nanostructured implant on osseointegration capacity–preliminary in vivo study. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 15533–15546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Midha, S.; Sharma, R.K.; Maurya, R.; Nigam, V.K.; Ghosh, S.; Balani, K. Antioxidant and antibacterial hydroxyapatite-based biocomposite for orthopedic applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 88, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sistanipour, E.; Meshkini, A.; Oveisi, H. Catechin-conjugated mesoporous hydroxyapatite nanoparticle: A novel nano-antioxidant with enhanced osteogenic property. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 169, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, Q.; Yang, W.; Hu, Y.; Shen, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, K. Osteogenesis of 3D printed porous Ti6Al4V implants with different pore sizes. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 84, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotz, E.M.; Berger, M.B.; Schwartz, Z.; Boyan, B.D. Regulation of osteoclasts by osteoblast lineage cells depends on titanium implant surface properties. Acta Biomater. 2018, 68, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, D.O.; Prowse, P.D.; Chrones, T.; Sims, S.M.; Hamilton, D.W.; Rizkalla, A.S.; Dixon, S.J. The differential regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast activity by surface topography of hydroxyapatite coatings. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 7215–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubert, M.; Vetsch, J.R.; Lehtoviita, I.; Sommer, M.; Zhao, F.; Studart, A.R.; Müller, R.; Hofmann, S. Scaffold Pore Geometry Guides Gene Regulation and Bone-like Tissue Formation in Dynamic Cultures. Tissue Eng. Part A 2021, 27, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, C.M.; Eichholz, K.F.; Hoey, D.A. The effect of pore size within fibrous scaffolds fabricated using melt electrowriting on human bone marrow stem cell osteogenesis. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 14, 065016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, N.; Zhu, M.; Qiu, Q.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, C.; Bai, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Lu, T. The contribution of pore size and porosity of 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds to osteogenesis. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 133, 112651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. 3D printed Ti6Al4V bone scaffolds with different pore structure effects on bone ingrowth. J. Biol. Eng. 2021, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.-Y.; Tsai, W.-B. Poly(dopamine)-Assisted Immobilization of Arg-Gly-Asp Peptides, Hydroxyapatite, and Bone Morphogenic Protein-2 on Titanium to Improve the Osteogenesis of Bone Marrow Stem Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 6975–6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliephake, H.; Scharnweber, D.; Dard, M.; Rö, S.; Sewing, A.; Hüttmann, C. Biological performance of biomimetic calcium phosphate coating of titanium implants in the dog mandible. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2003, 64A, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquia Edreira, E.R.; Wolke, J.G.C.; Aldosari, A.A.; Al-Johany, S.S.; Anil, S.; Jansen, J.A.; van den Beucken, J.J.J.P. Effects of calcium phosphate composition in sputter coatings on in vitro and in vivo performance. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Y. Controlled release of dopamine coatings on titanium bidirectionally regulate osteoclastic and osteogenic response behaviors. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 129, 112376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Honduvilla, N.; Coca, A.; Ortega, M.A.; Trejo, C.; Román, J.; Peña, J.; Cabañas, M.V.; Regi, M.V.; Buján, J. Improved connective integration of a degradable 3D-nano-apatite/agarose scaffold subcutaneously implanted in a rat model. J. Biomater. Appl. 2018, 33, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.; Wujczyk, M.; Dobrzynski, M.; Diakowska, D.; Wiglusz, K.; Wiglusz, R.J. In Vitro Assessment of Long-Term Fluoride Ion Release from Nanofluorapatite. Materials 2021, 14, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Duan, G.; Li, J.; Xiao, D.; Shi, F.; Duan, K.; Guo, T.; Fan, X.; Weng, J. Hydrothermal growth of biomimetic calcium phosphate network structure on titanium surface for biomedical application. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 16652–16660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).