Macro- and Micro-Level Behavioral Patterns in Simulation-Based Scientific Inquiry: Linking Processes to Performance Among Elementary Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Scientific Inquiry Processes and Cognitive Strategy Use

2.2. Scientific Inquiry Processes and Performance in Simulation-Based Inquiry Tasks

2.3. The Present Study and Research Questions

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

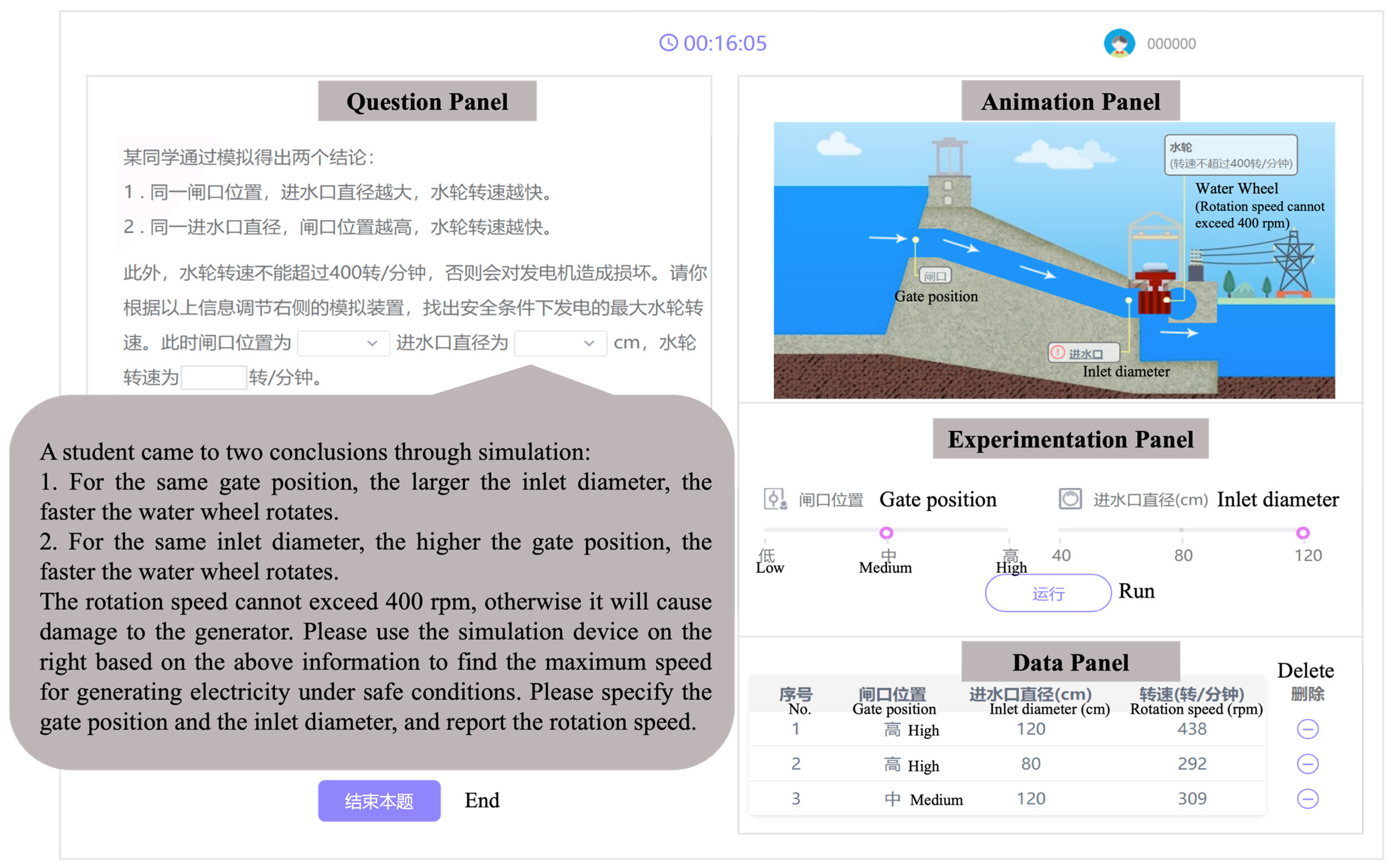

3.2. Simulation-Based Inquiry Task: Hydroelectric Power Plant

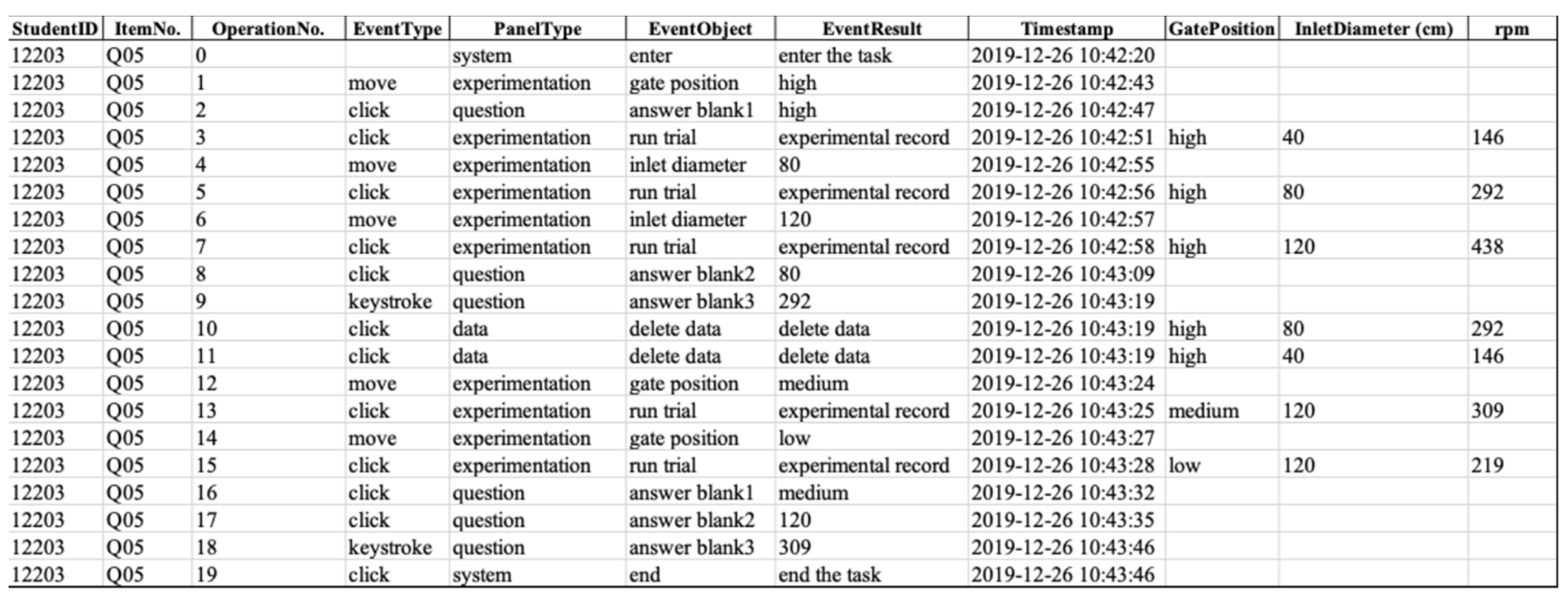

3.3. Behavior Coding Scheme

3.4. Statistical Analyses

3.4.1. Process Data Preprocessing

3.4.2. Task Performance Subgroup Formation

3.4.3. Macro-Level Analyses

3.4.4. Micro-Level Analyses

3.4.5. Analytical Environment

4. Results

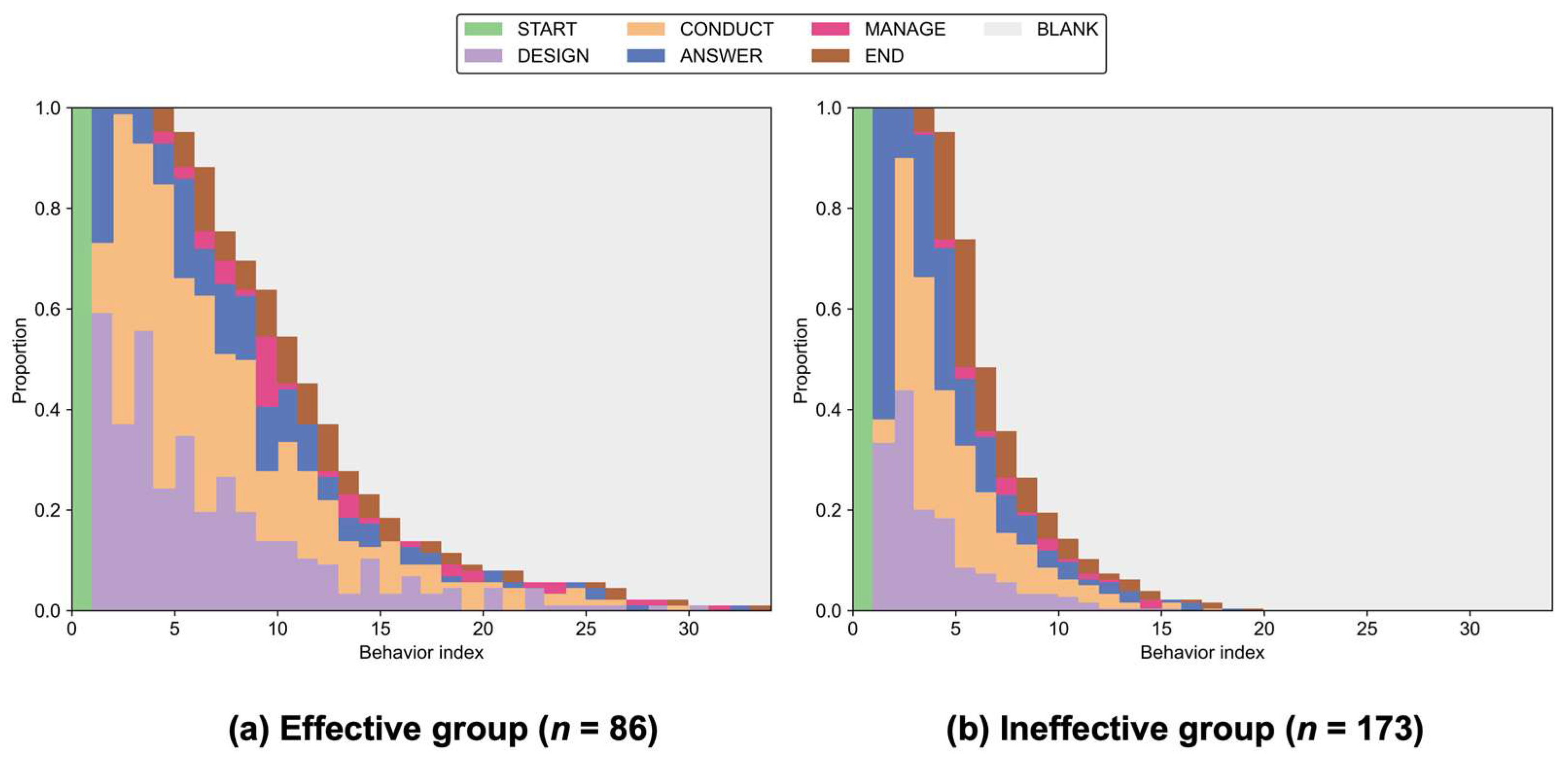

4.1. Macro-Level Inquiry Processes Across Effectiveness Groups (RQ1)

4.2. Micro-Level Inquiry Processes by Efficiency Within Effectiveness Groups (RQ2)

5. Discussion

5.1. Macro-Level Inquiry Patterns Across Effectiveness Groups

5.2. Micro-Level Inquiry Patterns by Efficiency Within Effectiveness Groups

5.3. Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| IRR | Incidence Rate Ratio |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Effectiveness Group | K | BIC | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective (n = 86) | 1 | 934.55 | 929.64 |

| 2 | 917.57 | 905.29 | |

| 3 | 929.61 | 909.97 | |

| 4 | 937.26 | 910.26 | |

| Ineffective (n = 173) | 1 | 1743.74 | 1737.44 |

| 2 | 1693.91 | 1678.14 | |

| 3 | 1699.21 | 1673.98 | |

| 4 | 1709.10 | 1674.42 |

| Effectiveness Group | Grouping Method | Efficiency Group | n (%) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective (n = 86) | Median split | Efficient | 27 (31%) | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Inefficient | 59 (69%) | 0.16 | 0.09 | ||

| Tertiles | Most efficient (T1) | 12 (14%) | 0.10 | 0.11 | |

| Middle efficient (T2) | 37 (43%) | 0.14 | 0.09 | ||

| Least efficient (T3) | 37 (43%) | 0.18 | 0.08 | ||

| Ineffective (n = 173) | Median split | Efficient | 107 (62%) | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Inefficient | 66 (38%) | 0.16 | 0.09 | ||

| Tertiles | Most efficient (T1) | 53 (31%) | 0.08 | 0.09 | |

| Middle efficient (T2) | 91 (53%) | 0.13 | 0.09 | ||

| Least efficient (T3) | 29 (17%) | 0.18 | 0.08 |

Appendix C

| Subsequences | Support (95%CI) | Student Count | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective | Ineffective | Effective | Ineffective | ||

| Frequent subsequences primarily for the Effective group | |||||

| <START, DESIGN> | 0.59 [0.49, 0.69] | 0.34 [0.27, 0.41] | 51 | 59 | <0.001 |

| <START, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.58 [0.48, 0.68] | 0.27 [0.21, 0.34] | 50 | 47 | <0.001 |

| <START, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.55 [0.44, 0.65] | 0.11 [0.08, 0.17] | 47 | 20 | <0.001 |

| <START, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.51 [0.41, 0.61] | 0.10 [0.07, 0.16] | 44 | 18 | <0.001 |

| <START, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.30 [0.22, 0.41] | 0.05 [0.02, 0.09] | 26 | 8 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.83 [0.73, 0.89] | 0.29 [0.23, 0.36] | 71 | 51 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.79 [0.69, 0.86] | 0.27 [0.21, 0.34] | 68 | 47 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER> | 0.57 [0.46, 0.67] | 0.18 [0.13, 0.25] | 49 | 32 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.51 [0.41, 0.61] | 0.13 [0.08, 0.18] | 44 | 22 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER, END> | 0.44 [0.34, 0.55] | 0.17 [0.12, 0.23] | 38 | 29 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.50 [0.40, 0.60] | 0.12 [0.08, 0.18] | 43 | 21 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER> | 0.31 [0.23, 0.42] | 0.08 [0.05, 0.13] | 27 | 14 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.31 [0.23, 0.42] | 0.03 [0.02, 0.07] | 27 | 6 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.31 [0.23, 0.42] | 0.03 [0.01, 0.07] | 27 | 5 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.94 [0.87, 0.97] | 0.78 [0.71, 0.83] | 81 | 135 | 0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.80 [0.71, 0.87] | 0.25 [0.19, 0.32] | 69 | 44 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.77 [0.67, 0.84] | 0.23 [0.17, 0.30] | 66 | 40 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER> | 0.55 [0.44, 0.65] | 0.16 [0.11, 0.22] | 47 | 28 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.45 [0.35, 0.56] | 0.11 [0.08, 0.17] | 39 | 20 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER, END> | 0.42 [0.32, 0.52] | 0.14 [0.10, 0.20] | 36 | 25 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.44 [0.34, 0.55] | 0.11 [0.07, 0.16] | 38 | 19 | <0.001 |

| Frequent subsequences primarily for the Ineffective group | |||||

| <START, ANSWER> | 0.27 [0.19, 0.37] | 0.61 [0.54, 0.68] | 23 | 107 | <0.001 |

| <START, ANSWER, DESIGN> | 0.23 [0.16, 0.33] | 0.43 [0.36, 0.51] | 20 | 75 | 0.002 |

| <START, ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.21 [0.14, 0.31] | 0.38 [0.31, 0.45] | 18 | 66 | 0.007 |

| <ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.35 [0.26, 0.45] | 0.51 [0.43, 0.58] | 30 | 88 | 0.021 |

| <ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER> | 0.13 [0.07, 0.21] | 0.34 [0.28, 0.42] | 11 | 60 | <0.001 |

| <ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER, END> | 0.13 [0.07, 0.21] | 0.34 [0.27, 0.41] | 11 | 59 | <0.001 |

Appendix D

| Source | Adjust Gate | Adjust Diameter | Run Trial | Initial Answer | Revise Answer | Remove Record | End Task | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | ||||||||

| Start Task | 0.05 [−0.23, 0.32] | −0.02 [−0.25, 0.20] | −0.25 [−0.51, −0.02] | 0.22 [0.03, 0.36] | — | — | — | |

| Adjust Gate | — | 0.06 [−0.14, 0.23] | 0.02 [−0.14, 0.20] | −0.06 [−0.13, 0.01] | 0.01 [−0.00, 0.03] | −0.04 [−0.11, 0.03] | 0.01 [−0.00, 0.02] | |

| Adjust Diameter | 0.08 [−0.01, 0.17] | — | −0.07 [−0.17, 0.02] | −0.01 [−0.05, 0.02] | 0.04 [0.01, 0.07] | −0.04 [−0.10, 0.02] | — | |

| Run Trial | 0.04 [−0.06, 0.16] | −0.15 [−0.29, −0.02] | 0.02 [−0.08, 0.12] | 0.08 [0.03, 0.13] | 0.08 [0.01, 0.15] | −0.11 [−0.19, −0.03] | 0.02 [0.01, 0.04] | |

| Initial Answer | −0.12 [−0.41, 0.14] | 0.04 [−0.13, 0.16] | 0.11 [0.04, 0.17] | — | — | — | −0.02 [−0.29, 0.27] | |

| Revise Answer | 0.08 [0.02, 0.16] | 0.06 [−0.00, 0.13] | 0.13 [0.04, 0.22] | — | — | 0.06 [−0.00, 0.14] | −0.33 [−0.43, −0.22] | |

| Remove Record | −0.11 [−0.38, 0.17] | −0.17 [−0.37, 0.02] | −0.02 [−0.35, 0.33] | 0.25 [0.02, 0.49] | 0.00 [−0.10, 0.14] | — | 0.05 [−0.00, 0.15] | |

| Source | Adjust Gate | Adjust Diameter | Run Trial | Initial Answer | Revise Answer | Remove Record | End Task | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target | ||||||||

| Start Task | −0.12 [−0.33, 0.07] | −0.11 [−0.28, 0.04] | 0.00 [−0.11, 0.08] | 0.23 [0.01, 0.45] | — | — | — | |

| Adjust Gate | — | 0.08 [−0.11, 0.27] | −0.16 [−0.34, 0.03] | −0.02 [−0.15, 0.07] | 0.08 [0.04, 0.13] | 0.01 [−0.00, 0.04] | — | |

| Adjust Diameter | −0.01 [−0.10, 0.09] | — | −0.07 [−0.17, 0.04] | 0.01 [−0.00, 0.03] | 0.02 [−0.00, 0.04] | 0.04 [0.01, 0.09] | 0.01 [−0.00, 0.02] | |

| Run Trial | −0.07 [−0.14, 0.00] | −0.17 [−0.27, −0.05] | 0.14 [0.04, 0.23] | −0.03 [−0.13, 0.06] | 0.14 [0.02, 0.26] | 0.00 [−0.07, 0.06] | −0.01 [−0.07, 0.03] | |

| Initial Answer | −0.08 [−0.31, 0.14] | 0.05 [−0.11, 0.19] | 0.08 [−0.08, 0.22] | — | — | — | −0.05 [−0.27, 0.15] | |

| Revise Answer | −0.05 [−0.16, 0.03] | 0.07 [0.03, 0.11] | 0.05 [0.02, 0.09] | — | — | 0.01 [−0.00, 0.02] | −0.08 [−0.18, 0.04] | |

| Remove Record | 0.13 [−0.03, 0.34] | −0.26 [−0.77, 0.08] | 0.39 [0.15, 0.62] | 0.14 [0.01, 0.30] | −0.39 [−0.77, 0.23] | — | — | |

References

- Anghel, E., Khorramdel, L., & von Davier, M. (2024). The use of process data in large-scale assessments: A literature review. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 12(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J. C., Kremer, K., & Mayer, J. (2014). Understanding students’ experiments—What kind of support do they need in inquiry tasks? International Journal of Science Education, 36(16), 2719–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R. S., Clarke-Midura, J., & Ocumpaugh, J. (2016). Towards general models of effective science inquiry in virtual performance assessments: Models of effective science inquiry. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 32(3), 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R. S. J. D., & Clarke-Midura, J. (2013). Predicting successful inquiry learning in a virtual performance assessment for science. In S. Carberry, S. Weibelzahl, A. Micarelli, & G. Semeraro (Eds.), User modeling, adaptation, and personalization (Vol. 7899, pp. 203–214). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-38844-6_17 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, Y., & von Davier, A. A. (2019). Process data in NAEP: Past, present, and future. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 44(6), 706–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaw, N., Kriek, J., & Lemmer, M. (2023). Insights from coherence in students’ scientific reasoning skills. Heliyon, 9(7), e17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. M., & Wang, W. F. (2020). Mining effective learning behaviors in a Web-based inquiry science environment. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 29(4), 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. (2010). The view of scientific inquiry conveyed by simulation-based virtual laboratories. Computers & Education, 55(3), 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Klahr, D. (1999). All other things being equal: Acquisition and transfer of the control of variables strategy. Child Development, 70(5), 1098–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, G.-L., Hsu, C.-Y., & Tsai, M.-J. (2022). Exploring how students interact with guidance in a physics simulation: Evidence from eye-movement and log data analyses. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(3), 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, G. E., Quellmalz, E. S., Davenport, J. L., Timms, M. J., Herrmann-Abell, C. F., Buckley, B. C., Jordan, K. A., Huang, C., & Flanagan, J. C. (2014). Comparing three online testing modalities: Using static, active, and interactive online testing modalities to assess middle school students’ understanding of fundamental ideas and use of inquiry skills related to ecosystems. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(4), 523–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, S., Veldkamp, B. P., & Eggen, T. J. H. M. (2015). Psychometric analysis of the performance data of simulation-based assessment: A systematic review and a Bayesian network example. Computers & Education, 85, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmann, B., Greiff, S., Naumann, J., Brandhuber, L., & Goldhammer, F. (2020). Exploring behavioural patterns during complex problem-solving. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(6), 933–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, M., & Erdem, M. (2020). Developing science process skills through mobile scientific inquiry. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 36, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emden, M., & Sumfleth, E. (2016). Assessing students’ experimentation processes in guided inquiry. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 14(1), 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mila, M., Andersen, C., & Rojo, N. E. (2011). Elementary students’ laboratory record keeping during scientific inquiry. International Journal of Science Education, 33(7), 915–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, J. D., Kim, Y. J., Sao Pedro, M. A., Kennedy, M., & Betts, C. G. (2015). Using educational data mining to assess students’ skills at designing and conducting experiments within a complex systems microworld. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 18, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobert, J. D., Sao Pedro, M., Raziuddin, J., & Baker, R. S. (2013). From log files to assessment metrics: Measuring students’ science inquiry skills Using educational data mining. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 22(4), 521–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhammer, F., Hahnel, C., Kroehne, U., & Zehner, F. (2021). From byproduct to design factor: On validating the interpretation of process indicators based on log data. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 9(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T., Shuai, L., Jiang, Y., & Arslan, B. (2023). Using process features to investigate scientific problem-solving in large-scale assessments. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1131019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiff, S., Wüstenberg, S., & Avvisati, F. (2015). Computer-generated log-file analyses as a window into students’ minds? A showcase study based on the PISA 2012 assessment of problem solving. Computers & Education, 91, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q., Borgonovi, F., & Paccagnella, M. (2021). Leveraging process data to assess adults’ problem-solving skills: Using sequence mining to identify behavioral patterns across digital tasks. Computers & Education, 166, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y. C., Cheung, L. Y. T., Wu, Y. J., Yang, F. Y., & Chiou, G. L. (2024). Eye movements in the manipulation of hands-on and computer-simulated scientific experiments: An examination of learning processes using entropy and lag sequential analyses. Instructional Science, 52(1), 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J., & Liu, M. (2022). Investigating navigational behavior patterns of students across at-risk categories within an open-ended serious game. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 27(1), 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, J. M., Scheiter, K., & Oschatz, K. (2017). How to sequence video modeling examples and inquiry tasks to foster scientific reasoning. Learning and Instruction, 52, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, J., Baur, A., & Möller, A. (2023). Learners’ challenges in understanding and performing experiments: A systematic review of the literature. Studies in Science Education, 59(2), 321–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruit, P. M., Oostdam, R. J., van den Berg, E., & Schuitema, J. A. (2018). Assessing students’ ability in performing scientific inquiry: Instruments for measuring science skills in primary education. Research in Science & Technological Education, 36(4), 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D., Iordanou, K., Pease, M., & Wirkala, C. (2008). Beyond control of variables: What needs to develop to achieve skilled scientific thinking? Cognitive Development, 23(4), 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazonder, A. W., & Kamp, E. (2012). Bit by bit or all at once? Splitting up the inquiry task to promote children’s scientific reasoning. Learning and Instruction, 22(6), 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Gobert, J., Graesser, A., & Dickler, R. (2018). Advanced educational technology for science inquiry assessment. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(2), 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Wang, T., Zheng, J., & Lajoie, S. P. (2025). A complex dynamical system approach to student engagement. Learning and Instruction, 98, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X. F., Hwang, G. J., Wang, J., Zhou, Y., Li, W., Liu, J., & Liang, Z. M. (2023). Effects of a contextualised reflective mechanism-based augmented reality learning model on students’ scientific inquiry learning performances, behavioural patterns, and higher order thinking. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(10), 6931–6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M. A., & Greiff, S. (2023). Process data in computer-based assessment: Challenges and opportunities in opening the black box. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 39(4), 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, K. E. (2004). Children’s understanding of scientific inquiry: Their conceptualization of uncertainty in investigations of their own design. Cognition and Instruction, 22(2), 219–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, I., de Mooij, S., Azevedo, R., Bannert, M., Järvelä, S., & Gašević, D. (2023). Measuring self-regulated learning and the role of AI: Five years of research using multimodal multichannel data. Computers in Human Behavior, 139, 107540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. (2012). A framework for K-12 science education: Practices, crosscutting concepts, and core ideas. National Academies Press. Available online: http://nap.edu/catalog/13165 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ober, T. M., Hong, M. R., Rebouças-Ju, D. A., Carter, M. F., Liu, C., & Cheng, Y. (2021). Linking self-report and process data to performance as measured by different assessment types. Computers & Education, 167, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J., & Allchin, D. (2025). Science literacy in the twenty-first century: Informed trust and the competent outsider. International Journal of Science Education, 47(15–16), 2134–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S. A. N., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, M., Wallner, G., & Kriglstein, S. (2016). Using lag-sequential analysis for understanding interaction sequences in visualizations. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 96, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quellmalz, E. S., Timms, M. J., Silberglitt, M. D., & Buckley, B. C. (2012). Science assessments for all: Integrating science simulations into balanced state science assessment systems. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(3), 363–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Reith, M., & Nehring, A. (2020). Scientific reasoning and views on the nature of scientific inquiry: Testing a new framework to understand and model epistemic cognition in science. International Journal of Science Education, 42(16), 2716–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnebeck, S., Bernholt, S., & Ropohl, M. (2016). Searching for a common ground—A literature review of empirical research on scientific inquiry activities. Studies in Science Education, 52(2), 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellinger, J., Mendenhall, A., Alemanne, N. D., Southerland, S. A., Sampson, V., Douglas, I., Kazmer, M. M., & Marty, P. F. (2017). “Doing science” in elementary school: Using digital technology to foster the development of elementary students’ understandings of scientific inquiry. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(8), 4635–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, M., Pickal, A. J., Brandl, L., & Krieger, F. (2024). VOTAT in Action: Exploring epistemic activities in knowledge-lean problem-solving processes. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 232(2), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L., Wei, B., & Chen, F. (2025). An exploratory process mining on students’ complex problem-solving behavior: The distinct patterns and related factors. Computers & Education, 238, 105398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, M., Azevedo, R., Bradbury, A. E., Millar, G. C., & Lester, J. (2018). Using sequence mining to reveal the efficiency in scientific reasoning during STEM learning with a game-based learning environment. Learning and Instruction, 54, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teig, N. (2024). Uncovering student strategies for solving scientific inquiry tasks: Insights from student process data in PISA. Research in Science Education, 54(2), 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teig, N., Scherer, R., & Kjærnsli, M. (2020). Identifying patterns of students’ performance on simulated inquiry tasks using PISA 2015 log-file data. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(9), 1400–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulitzsch, E., He, Q., & Pohl, S. (2022). Using sequence mining techniques for understanding incorrect behavioral patterns on interactive tasks. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 47(1), 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, A. M., Eysink, T. H. S., & de Jong, T. (2016). Ability-related differences in performance of an inquiry task: The added value of prompts. Learning and Individual Differences, 47, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, G., & Drake, F. L. (2009). Python 3 reference manual. CreateSpace. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C., Seah, Y. Y., & Magana, A. J. (2018). Students’ experimentation strategies in design: Is process data enough? Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 26(5), 1903–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D. V., & Simmie, G. M. (2025). Assessing scientific inquiry: A systematic literature review of tasks, tools and techniques. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 23(4), 871–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. D., Cock, J. M., Käser, T., & Bumbacher, E. (2023). A systematic review of empirical studies using log data from open-ended learning environments to measure science and engineering practices. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(1), 192–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C. T., Liu, C. C., Chang, H. Y., Chang, C. J., Chang, M. H., Fan Chiang, S. H., Yang, C. W., & Hwang, F. K. (2020). Students’ guided inquiry with simulation and its relation to school science achievement and scientific literacy. Computers & Education, 149, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Zhang, S., Guo, J., & Xin, T. (2024). Biclustering of log data: Insights from a computer-based complex problem solving assessment. Journal of Intelligence, 12(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, M. J. (2001). SPADE: An efficient algorithm for mining frequent sequences. Machine Learning, 42(1), 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Hu, W., Bai, H., & Lyu, Y. (2025). Applying machine learning to intelligent assessment of scientific creativity based on scientific knowledge structure and eye-tracking data. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 34(2), 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Xing, W., & Zhu, G. (2019). Examining sequential patterns of self- and socially shared regulation of STEM learning in a CSCL environment. Computers & Education, 136, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Bai, X., Yang, Y., & Xu, C. (2024). Exploring the effects and inquiry process behaviors of fifth-grade students using Predict-Observe-Explain strategy in virtual inquiry learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 33(4), 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, C. (2007). The development of scientific thinking skills in elementary and middle school. Developmental Review, 27(2), 172–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cognitive Component | Macro-Level Behavior | Micro-Level Behavior | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence Collection | DESIGN | Adjust Gate | The student adjusts the gate position (Low/Medium/High) in the Experimentation Panel. |

| Adjust Diameter | The student adjusts the inlet diameter (40 cm/80 cm/120 cm) in the Experimentation Panel. | ||

| CONDUCT | Run Trial | The student clicks the “Run” button to conduct an experimental trial; the system automatically records the resulting Gate × Diameter condition in the Data Panel. | |

| Evidence Evaluation | ANSWER | Initial Answer | The student provides a first response for this question in the Question Panel. |

| Revise Answer | The student later returns to the Question Panel and modifies a previous response for this question. | ||

| MANAGE | Remove Record | The student deletes a recorded row of data in the Data Panel. | |

| Task Control | START | Start Task | The student enters the task (the first logged behavior event for this task). |

| END | End Task | The student clicks the “End” button to end the task and submits final answers. |

| Behavior | Effectiveness Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective (n = 86) | Ineffective (n = 173) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | IRR (95% CI) | p | |

| START | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | — | — |

| DESIGN | 3.74 | 2.63 | 1.52 | 1.33 | 1.53 [1.38, 1.69] | <0.001 |

| CONDUCT | 4.20 | 2.58 | 2.01 | 1.60 | 1.30 [1.19, 1.42] | <0.001 |

| ANSWER | 1.62 | 0.74 | 1.82 | 0.61 | 0.56 [0.48, 0.65] | <0.001 |

| MANAGE | 0.49 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.51 | 1.88 [1.10, 3.20] | 0.020 |

| END | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | — | — |

| Subsequences | Support (95%CI) | Student Count | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective | Ineffective | Effective | Ineffective | ||

| Frequent subsequences primarily for the Effective group | |||||

| <START, DESIGN> | 0.59 [0.49, 0.69] | 0.34 [0.27, 0.41] | 51 | 59 | <0.001 |

| <START, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.58 [0.48, 0.68] | 0.27 [0.21, 0.34] | 50 | 47 | <0.001 |

| <START, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.55 [0.44, 0.65] | 0.11 [0.08, 0.17] | 47 | 20 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.83 [0.73, 0.89] | 0.29 [0.23, 0.36] | 71 | 51 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.79 [0.69, 0.86] | 0.27 [0.21, 0.34] | 68 | 47 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER> | 0.57 [0.46, 0.67] | 0.18 [0.13, 0.25] | 49 | 32 | <0.001 |

| <CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.51 [0.41, 0.61] | 0.13 [0.08, 0.18] | 44 | 22 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.94 [0.87, 0.97] | 0.78 [0.71, 0.83] | 81 | 135 | 0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN> | 0.80 [0.71, 0.87] | 0.25 [0.19, 0.32] | 69 | 44 | <0.001 |

| <DESIGN, CONDUCT, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.77 [0.67, 0.84] | 0.23 [0.17, 0.30] | 66 | 40 | <0.001 |

| Frequent subsequences primarily for the Ineffective group | |||||

| <START, ANSWER> | 0.27 [0.19, 0.37] | 0.61 [0.54, 0.68] | 23 | 107 | <0.001 |

| <START, ANSWER, DESIGN> | 0.23 [0.16, 0.33] | 0.43 [0.36, 0.51] | 20 | 75 | 0.002 |

| <START, ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.21 [0.14, 0.31] | 0.38 [0.31, 0.45] | 18 | 66 | 0.007 |

| <ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT> | 0.35 [0.26, 0.45] | 0.51 [0.43, 0.58] | 30 | 88 | 0.021 |

| <ANSWER, DESIGN, CONDUCT, ANSWER> | 0.13 [0.07, 0.21] | 0.34 [0.28, 0.42] | 11 | 60 | <0.001 |

| Effectiveness Group | Efficiency Profile | Completion Time | Sequence Length | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Effective (n = 86) | Efficient (n = 72) | 81.01 | 27.58 | 11.92 | 4.40 |

| Inefficient (n = 14) | 196.71 | 45.59 | 20.50 | 8.14 | |

| Ineffective (n = 173) | Efficient (n = 151) | 62.09 | 20.05 | 7.86 | 3.08 |

| Inefficient (n = 22) | 144.09 | 42.63 | 9.55 | 3.40 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Hu, A.; Yuan, L.; Tian, W.; Xin, T. Macro- and Micro-Level Behavioral Patterns in Simulation-Based Scientific Inquiry: Linking Processes to Performance Among Elementary Students. J. Intell. 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14010006

Wang S, Hu A, Yuan L, Tian W, Xin T. Macro- and Micro-Level Behavioral Patterns in Simulation-Based Scientific Inquiry: Linking Processes to Performance Among Elementary Students. Journal of Intelligence. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shuang, An Hu, Lu Yuan, Wei Tian, and Tao Xin. 2026. "Macro- and Micro-Level Behavioral Patterns in Simulation-Based Scientific Inquiry: Linking Processes to Performance Among Elementary Students" Journal of Intelligence 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14010006

APA StyleWang, S., Hu, A., Yuan, L., Tian, W., & Xin, T. (2026). Macro- and Micro-Level Behavioral Patterns in Simulation-Based Scientific Inquiry: Linking Processes to Performance Among Elementary Students. Journal of Intelligence, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence14010006