Achievement Goal Profiles and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Literacy: A Person-Centered Approach in Third Grade Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Achievement Goals Framework

1.2. Emergence of Achievement Goal Profiles

1.3. Achievement Goal Profiles

1.4. Achievement Goal Profiles and Academic Performance

1.5. Achievement Goals Profiles and Gender Differences

1.6. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sensitivity Power Analysis

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.5. Descriptive Statistics and Missing Data Handling

2.6. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

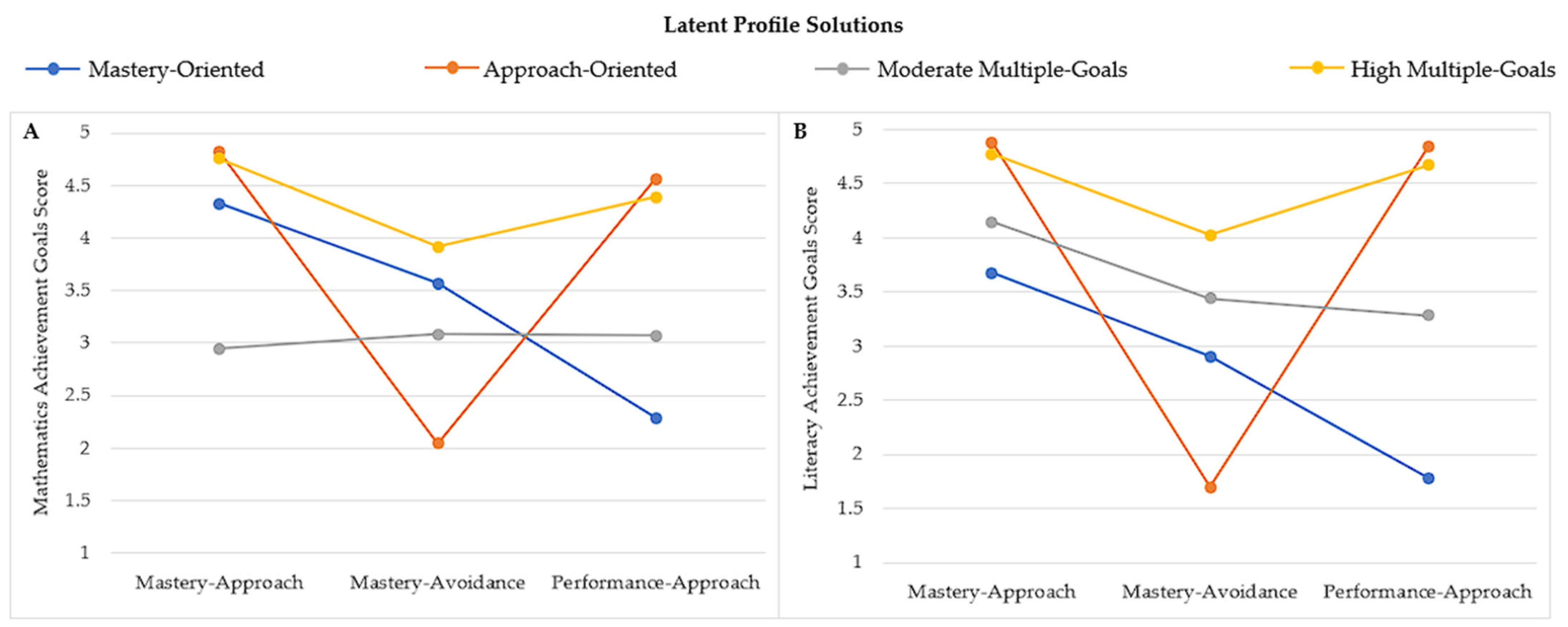

3.2. Achievement Goal Profiles Across Academic Domains

3.3. Gender Differences in Profile Membership

3.4. Associations Between Achievement Goal Profiles and Mathematics and Literacy Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Achievement Goal Profiles Among Primary School Students

4.2. Gender Differences

4.3. Achievement Goal Profiles and Mathematics and Literacy Performance

4.4. Implications for Practice and Policy Makers

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LPA | Latent Profile Analysis |

| SPI | Social Position Index |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of Covariance |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

References

- Abdullah, Hazlina, Mohd Muzhafar Idrus, Xuesong Andy Gao, and Siti Salmiah Muhammad. 2024. Teacher Cognition of Gender Gap in the English Language Literacy: A Malaysian Narrative. SAGE Open 14: 21582440241305200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbuga, Bulent, Ping Xiang, and Ron Everett McBride. 2015. Relationship between Achievement Goals and Students’ Self-Reported Personal and Social Responsibility Behaviors. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 18: E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, Hirotugu. 1998. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike. Edited by Emanuel Parzen, Kunio Tanabe and Genshiro Kitagawa. New York: Springer Series in Statistics, pp. 215–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadabi, Amal, and Aryn Camille Karpinski. 2019. Grit, Self-Efficacy, Achievement Orientation Goals, and Academic Performance in University Students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25: 519–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, Carole. 1992. Classrooms: Goals, Structures, and Student Motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology 84: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Min, Xiao Zhang, Ying Wang, Jingxin Zhao, and Lingyue Kong. 2022. Reciprocal Relations between Achievement Goals and Academic Performance in a Collectivist Higher Education Context: A Longitudinal Study. European Journal of Psychology of Education 37: 971–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, Eric Michael, and Carol Midgley. 1997. Changes in Achievement Goal Orientations, Perceived Academic Competence, and Grades across the Transition to Middle-Level Schools. Contemporary Educational Psychology 22: 269–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Christine Lynn, and Morgan DeBusk-Lane. 2018. Motivation Belief Profiles in Science: Links to Classroom Goal Structures and Achievement. Learning and Individual Differences 67: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, Lisa, Marko Lüftenegger, Takuya Yanagida, Barbara Schober, and Christiane Spiel. 2019. The Role of Within-class Consensus on Mastery Goal Structures in Predicting Socio-emotional Outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology 89: 239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Kenneth, and Judith Harackiewicz. 2001. Achievement Goals and Optimal Motivation: Testing Multiple Goal Models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 80: 706–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Lin, Sarah-Jane Leslie, and Andrei Cimpian. 2017. Gender Stereotypes about Intellectual Ability Emerge Early and Influence Children’s Interests. Science 355: 389–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, Alisée, Mickaël Jury, Marie-Christine Toczek, and Céline Darnon. 2019. Are Performance-Avoidance Goals Always Deleterious for Academic Achievement in College? The Moderating Role of Social Class. Social Psychology of Education 22: 539–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, Elizabeth, Katherine Muenks, Dorainne Green, and Mary Murphy. 2019. STEM Faculty Who Believe Ability Is Fixed Have Larger Racial Achievement Gaps and Inspire Less Student Motivation in Their Classes. Science Advances 5: eaau4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, Francisco, and Ana Belén García Berbén. 2009. University Students’ Achievement Goals and Approaches to Learning in Mathematics. British Journal of Educational Psychology 79: 131–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Amanda, and Shems Marzouq. 2011. Special Edition Paper: The 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework in Primary School: Do Young Children Pursue Mastery-Avoidance Goals? Education and Training. Psychology of Education Review 36: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, Kyriakos. 2018. The 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework in Preadolescents: Factorial and Dimensional Endorsement in the Greek Elementary Context. Education Research Journal 8: 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Yoonkyung, Mimi Bong, and Sung-il Kim. 2020. Performing under Challenge: The Differing Effects of Ability and Normative Performance Goals. Journal of Educational Psychology 112: 823–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvencek, Dario, Andrew Meltzoff, and Anthony Galt Greenwald. 2011. Math-Gender Stereotypes in Elementary School Children. Child Development 82: 766–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnon, Céline, and Fabrizio Butera. 2005. Buts d’Accomplissement, Stratégies d’Étude et Motivation Intrinsèque: Présentation d’un Domaine de Recherche et Validation Française de l’Échelle D’Elliot et Mcgregor (2001). [Achievement Goals, Study Strategies, and Intrinsic Motivation: Presentation of a Research Field and Validation of the French Version of Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) Scale]. L’Année Psychologique 105: 105–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnon, Céline, Mickaël Jury, and Cristina Aelenei. 2018. Who Benefits from Mastery-Approach and Performance-Approach Goals in College? Students’ Social Class as a Moderator of the Link between Goals and Grade. European Journal of Psychology of Education 33: 713–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauphant, Fannie, Franck Evain, Marine Guillerm, Catherine Simon, and Thierry Rocher. 2023. L’Indice de Position Sociale (IPS): Un Outil Statistique pour Décrire les Inégalités Sociales entre Établissements. [The Social Position Index (SPI): A Statistical Tool to Describe Social Inequalities between Schools]. Note d’information de la DEPP 23.16: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dompnier, Benoît, Céline Darnon, and Fabrizio Butera. 2013. When Performance-Approach Goals Predict Academic Achievement and When They Do Not: A Social Value Approach. The British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 587–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, Carol, and Ellen Leggett. 1988. A Social-Cognitive Approach to Motivation and Personality. Psychological Review 95: 256–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Jacquelynne Sue, Carol Midgley, Allan Wigfield, Christy Miller Buchanan, David Reuman, Constance Flanagan, and Douglas Mac Iver. 1993. Development during Adolescence: The Impact of Stage-Environment Fit on Young Adolescents’ Experiences in Schools and in Families. American Psychologist 48: 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, Andrew, and Holly McGregor. 2001. A 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 80: 501–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, Andrew, and Judith Harackiewicz. 1996. Approach and Avoidance Achievement Goals and Intrinsic Motivation: A Mediational Analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 461–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, Andrew, and Marcy Church. 1997. A Hierarchical Model of Approach and Avoidance Achievement Motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72: 218–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else-Quest, Nicole, Janet Shibley Hyde, Hill Goldsmith, and Carol Van Hulle. 2006. Gender Differences in Temperament: A Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin 132: 33–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Weihua, and Cathy Williams. 2010. The Effects of Parental Involvement on Students’ Academic Self-Efficacy, Engagement and Intrinsic Motivation. Educational Psychology 30: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Albert-Georg Lang, and Axel Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, Sara, Suzanne Pieper, and Kenneth Barron. 2004. Examining the Psychometric Properties of the Achievement Goal Questionnaire in a General Academic Context. Educational and Psychological Measurement 64: 365–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Ana-Lisa, and Christopher Wolters. 2006. The Relation between Perceived Parenting Practices and Achievement Motivation in Mathematics. Journal of Research in Childhood Education 21: 203–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, Catherine, Joshua Aronson, and Michael Inzlicht. 2003. Improving Adolescents’ Standardized Test Performance: An Intervention to Reduce the Effects of Stereotype Threat. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 24: 645–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, Wendy, and Maria Slowiaczek. 1994. Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Schooling: A Multidimensional Conceptualization and Motivational Model. Child Development 65: 237–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Jiesi, Xiang Hu, Andrew Elliot, Herbert Marsh, Kou Murayama, Geetanjali Basarkod, Philip Parker, and Theresa Dicke. 2023. Mastery-Approach Goals: A Large-Scale Cross-Cultural Analysis of Antecedents and Consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 125: 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, Judith, Kenneth Barron, John Tauer, and Andrew Elliot. 2002a. Predicting Success in College: A Longitudinal Study of Achievement Goals and Ability Measures as Predictors of Interest and Performance from Freshman Year through Graduation. Journal of Educational Psychology 94: 562–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, Judith, Kenneth Barron, Paul Pintrich, Andrew Elliot, and Todd Thrash. 2002b. Revision of Achievement Goal Theory: Necessary and Illuminating. Journal of Educational Psychology 94: 638–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, David, Tom Arthur, Samuel James Vine, Harith Rusydin Abd Rahman, Jiayi Liu, Feng Han, and Mark Wilson. 2023. The Effect of Performance Pressure and Error-Feedback on Anxiety and Performance in an Interceptive Task. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1182269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornstra, Lisette, Marieke Majoor, and Thea Peetsma. 2017. Achievement Goal Profiles and Developments in Effort and Achievement in Upper Elementary School. British Journal of Educational Psychology 87: 606–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulleman, Chris, Sheree Schrager, Shawn Bodmann, and Judith Harackiewicz. 2010. A Meta-Analytic Review of Achievement Goal Measures: Different Labels for the Same Constructs or Different Constructs with Similar Labels? Psychological Bulletin 136: 422–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Leong Yeok, and Woon Chia Liu. 2012. 2 × 2 Achievement Goals and Achievement Emotions: A Cluster Analysis of Students’ Motivation. European Journal of Psychology of Education 27: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen in de Wal, Joost, Lisette Hornstra, Frans Prins, Thea Peetsma, and Ineke van der Veen. 2015. The Prevalence, Development and Domain Specificity of Elementary School Students’ Achievement Goal Profiles. Educational Psychology 36: 1303–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowkar, Bahram, Javad Kojuri, Naeimeh Kohoulat, and Ali Asghar Hayat. 2014. Academic Resilience in Education: The Role of Achievement Goal Orientations. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism 2: 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Avi, and Martin Maehr. 2007. The Contributions and Prospects of Goal Orientation Theory. Educational Psychology Review 19: 141–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Avi, Michael Middleton, Tim Urdan, and Carol Midgley. 2002. Achievement Goals and Goal Structures. In Goals, Goal Structures, and Patterns of Adaptive Learning. Edited by Carol Midgley. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 21–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, Manu. 2008. Productive Failure. Cognition and Instruction 26: 379–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, Manu. 2014. Productive Failure in Learning Math. Cognitive Science 38: 1008–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, Manu, and Katerine Bielaczyc. 2012. Designing for Productive Failure. Journal of the Learning Sciences 21: 45–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz-Vago, Inbar, and Moti Benita. 2024. Mastery-Approach and Performance-Approach Goals Predict Distinct Outcomes during Personal Academic Goal Pursuit. The British Journal of Educational Psychology 94: 309–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kyung Min, Yoon-Ja Park, and Mimi Bong. 2025. Adolescent Achievement Goal Profiles and Their Relationships with Predictors and Outcomes. Social Psychology of Education 28: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenka, Alison, Lisa Linnenbrink-Garcia, Hannah Moshontz, Kayla Atkinson, Carmen Sanchez, and Harris Cooper. 2021. A Meta-Analysis on the Impact of Grades and Comments on Academic Motivation and Achievement: A Case for Written Feedback. Educational Psychology 41: 922–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, Theodoros. 2018. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 9: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, You-kyung, Eunsoo Cho, and Cary Roseth. 2020. Interpersonal Predictors and Outcomes of Motivational Profiles in Middle School. Learning and Individual Differences 81: 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenknecht, Martijn, Priscilla Hompus, and Marieke van der Schaaf. 2019. Feedback Seeking Behaviour in Higher Education: The Association with Students’ Goal Orientation and Deep Learning Approach. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 44: 1069–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Guofang, Zhen Lin, Fubiao Zhen, Lee Gunderson, and Ryan Ji. 2023. Home Literacy Environment and Early Biliteracy Engagement and Attainment: A Gendered Perspective. Bilingual Research Journal 46: 258–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhanov, Maxim, Tomasz Bloniewski, Evgeniia Alenina, Yulia Kovas, and Xinlin Zhou. 2024. Anxiety and performance in high-achieving adolescents: Associations among 8 general and specific anxiety measures and 13 school grades. Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Roderick Joseph Alexander. 1988. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83: 1198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loose, Florence, Isabelle Régner, Alexandre Morin, and Florence Dumas. 2012. Are Academic Discounting and Devaluing Double-Edged Swords? Their Relations to Global Self-Esteem, Achievement Goals, and Performance among Stigmatized Students. Journal of Educational Psychology 104: 713–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Wenshu, Scott Paris, David Hogan, and Zhiqiang Luo. 2011. Do Performance Goals Promote Learning? A Pattern Analysis of Singapore Students’ Achievement Goals. Contemporary Educational Psychology 36: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjar, Nir, Gil Zalsman, Abraham Weizman, Shaul Lev-Ran, and Gal Shoval. 2018. Predictors of Developing Mathematics Anxiety among Middle-School Students: A 2-Year Prospective Study. International Journal of Psychology 53: 426–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, Judith Lynn, and Kathleen Holt. 1993. A Pattern Analysis of Students’ Achievement Goals. Journal of Educational Psychology 85: 582–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, Judith Lynn, Eric Anderman, and Lynley Anderman. 2006. Classroom Goal Structure, Student Motivation, and Academic Achievement. Annual Review of Psychology 57: 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, Judith Lynn, Phillip Herman, and Barbara McCombs. 2003. Relations of Learner-Centered Teaching Practices to Adolescents’ Achievement Goals. International Journal of Educational Research 39: 457–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, Michael, and Carol Midgley. 1997. Avoiding the Demonstration of Lack of Ability: An Underexplored Aspect of Goal Theory. Journal of Educational Psychology 89: 710–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, Carol, Avi Kaplan, and Michael Middleton. 2001. Performance-Approach Goals: Good for What, for Whom, under What Circumstances, and at What Cost? Journal of Educational Psychology 93: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Kou, and Andrew Elliot. 2009. The Joint Influence of Personal Achievement Goals and Classroom Goal Structures on Achievement-Relevant Outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology 101: 432–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, Bengt, and Linda Muthén. 2000. Integrating Person-Centered and Variable-Centered Analyses: Growth Mixture Modeling with Latent Trajectory Classes. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 24: 882–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, John. 1984. Achievement Motivation: Conceptions of Ability, Subjective Experience, Task Choice, and Performance. Psychological Review 91: 328–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Hoi Kwan. 2016. Singapore Primary Students’ Pursuit of Multiple Achievement Goals: A Latent Profile Analysis. The Journal of Early Adolescence 38: 220–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylund, Karen, Tihomir Asparouhov, and Bengt Muthén. 2007. Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Structural Equation Modeling 14: 535–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, Dena, Kenneth Barron Miller, and Susan Davis. 2007. A Latent Profile Analysis of College Students’ Achievement Goal Orientation. Contemporary Educational Psychology 32: 8–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, Huy Phan. 2010. Empirical Model and Analysis of Mastery and Performance-Approach Goals: A Developmental Approach. Educational Psychology 30: 547–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, Paul Richard. 2000. The Role of Goal Orientation in Self-Regulated Learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation. Edited by Monique Boekaerts, Paul R. Pintrich and Moshe Zeidner. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 451–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, Paul Richard. 2003. A Motivational Science Perspective on the Role of Student Motivation in Learning and Teaching Contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology 95: 667–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, Eva Marie, Elizabeth Moorman, and Scott Litwack. 2007. The How, Whom, and Why of Parents’ Involvement in Children’s Academic Lives: More Is Not Always Better. Review of Educational Research 77: 373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulfrey, Caroline, Céline Buchs, and Fabrizio Butera. 2011. Why Grades Engender Performance-Avoidance Goals: The Mediating Role of Autonomous Motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology 103: 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repeykova, Vlada, Teemu Toivainen, Maxim Likhanov, Kim van Broekhoven, and Yulia Kovas. 2024. Nothing but Stereotypes? Negligible Sex Differences across Creativity Measures in Science, Arts, and Sports Adolescent High Achievers. The Journal of Creative Behavior 58: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocher, Thierry. 2016. Construction d’un Indice de Position Sociale Des Élèves. [Construction of a Social Position Index for Students]. Éducation & Formations 90: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeser, Robert William, Carol Midgley, and Timothy Urdan. 1996. Perceptions of the School Psychological Environment and Early Adolescents’ Psychological and Behavioral Functioning in School: The Mediating Role of Goals and Belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology 88: 408–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, Gideon. 1978. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. The Annals of Statistics 6: 461–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, Malte, and Elke Wild. 2012. Prevalence, Stability, and Functionality of Achievement Goal Profiles in Mathematics from Third to Seventh Grade. Contemporary Educational Psychology 37: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, Malte, Maike Trautner, Nadine Pütz, Salome Fabianek, Gunnar Lemmer, Fani Lauermann, and Linda Wirthwein. 2022. Why Do Students Use Strategies That Hurt Their Chances of Academic Success? A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents of Academic Self-Handicapping. Journal of Educational Psychology 114: 576–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, Malte, Ricarda Steinmayr, and Birgit Spinath. 2016. Achievement Goal Profiles in Elementary School: Antecedents, Consequences, and Longitudinal Trajectories. Contemporary Educational Psychology 46: 164–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclove, Stanley. 1987. Application of Model-Selection Criteria to Some Problems in Multivariate Analysis. Psychometrika 52: 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senko, Corwin, and Blair Dawson. 2017. Performance-Approach Goal Effects Depend on How They Are Defined: Meta-Analytic Evidence from Multiple Educational Outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology 109: 574–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, Georgios. 2005. Goal Orientation, Academic Achievement, and Depression: Evidence in Favor of a Revised Goal Theory Framework. Journal of Educational Psychology 97: 366–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, Georgios, and Athanasios Mouratidis. 2008. Forced Choice versus Open-Ended Assessments of Goal Orientations: A Descriptive Study. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 21: 217–46. [Google Scholar]

- Soncini, Annalisa, Emilio Paolo Visintin, Maria Cristina Matteucci, Carlo Tomasetto, and Fabrizio Butera. 2022. Positive Error Climate Promotes Learning Outcomes through Students’ Adaptive Reactions towards Errors. Learning and Instruction 80: 101627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Steven, Claude Steele, and Diane Quinn. 1999. Stereotype Threat and Women’s Math Performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 35: 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, Gabriele, and Markus Dresel. 2015. A Constructive Error Climate as an Element of Effective Learning Environments. Psychological Test and Assessment Modeling 57: 262–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tapola, Anna, Tomi Jaakkola, and Markku Niemivirta. 2014. The Influence of Achievement Goal Orientations and Task Concreteness on Situational Interest. The Journal of Experimental Education 82: 455–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, Michelle, Neil Brewer, and Paul Williamson. 2002. The Influence of Motives and Goal Orientation on Feedback Seeking. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 75: 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulis, Maria, Gabriele Steuer, and Markus Dresel. 2016. Learning from Errors: A Model of Individual Processes. Frontline Learning Research 4: 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen-Soini, Heta, Katariina Salmela-Aro, and Markku Niemivirta. 2012. Achievement Goal Orientations and Academic Well-Being across the Transition to Upper Secondary Education. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. 2017. Growth Mindset, Performance Avoidance, and Academic Behaviors in Clark County School District. REL 2017-226. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/rel/regions/west/pdf/REL_2017226.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Van Yperen, Nico. 2006. A Novel Approach to Assessing Achievement Goals in the Context of the 2 × 2 Framework: Identifying Distinct Profiles of Individuals with Different Dominant Achievement Goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 32: 1432–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veermans, Marjaana, and Anna Tapola. 2004. Primary School Students’ Motivational Profiles in Longitudinal Settings. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 48: 373–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirthwein, Linda, and Ricarda Steinmayr. 2021. Performance-Approach Goals: The Operationalization Makes the Difference. European Journal of Psychology of Education 36: 1199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirthwein, Linda, Jörn Rüdiger Sparfeldt, Martin Pinquart, Joanna Wegerer, and Ricarda Steinmayr. 2013. Achievement Goals and Academic Achievement: A Closer Look at Moderating Factors. Educational Research Review 10: 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wormington, Stephanie Virgine, and Lisa Linnenbrink-Garcia. 2017. A New Look at Multiple Goal Pursuit: The Promise of a Person-Centered Approach. Educational Psychology Review 29: 407–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Shiyuan, Yan Liu, and Lu Bai. 2017. Parenting Styles and Adolescents’ School Adjustment: Investigating the Mediating Role of Achievement Goals within the 2 × 2 Framework. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Junlin, Pia Kreijkes, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2023. Interconnected Trajectories of Achievement Goals, Academic Achievement, and Well-Being: Insights from an Expanded Goal Framework. Learning and Individual Differences 108: 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ying, Rainer Watermann, and Annabell Daniel. 2016. Are Multiple Goals in Elementary Students Beneficial for Their School Achievement? A Latent Class Analysis. Learning and Individual Differences 51: 100–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ying, Rainer Watermann, and Annabell Daniel. 2023. The Sustained Effects of Achievement Goal Profiles on School Achievement across the Transition to Secondary School. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 52: 2078–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Xiaoli, Lifan Zhang, and Meilin Yao. 2018. Parental Involvement and Chinese Elementary Students’ Achievement Goals: The Moderating Role of Parenting Style. Educational Studies 44: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (0 = girl, 1 = boy) | ||||||||||||

| 2. SES | 110.82 | 34.62 | −.04 | |||||||||

| 3. Mathematics Performance | 13.66 | 3.21 | .15 * | .25 *** | ||||||||

| 4. Mathematics Mastery-Approach Goal | 4.51 | 0.70 | −.06 | −.03 | .14 | |||||||

| 5. Mathematics Mastery-Avoidance Goal | 3.25 | 1.16 | −.19 * | −.22 ** | −.22 ** | .13 | ||||||

| 6. Mathematics Performance-Approach Goal | 4.07 | 1.06 | −.08 | −.14 | −.04 | .49 *** | .05 | |||||

| 7. Literacy Performance | 12.36 | 3.92 | −.25 *** | .26 *** | .49 *** | .07 | −.27 *** | −.007 | ||||

| 8. Literacy Mastery-Approach Goal | 4.49 | 0.69 | −.04 | −.12 | −.05 | .45 ** | .05 | .48 *** | −.02 | |||

| 9. Literacy Mastery-Avoidance Goal | 3.33 | 1.21 | −.20 * | −.14 | −.19 ** | .09 | .58 *** | .06 | −.22 ** | .06 | ||

| 10. Literacy Performance-Approach Goal | 3.98 | 1.11 | .002 | −.17 * | −.04 | .36 *** | .05 | .75 *** | −.01 | .56 *** | .05 |

| Literacy Profiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Mathematics Profiles | Mastery-Oriented | Approach-Oriented | Moderate Multiple-Goals | High Multiple-Goals |

| Girls | Mastery-Oriented | 50.00% | 0.00% | 50.00% | 0.00% |

| Approach-Oriented | 13.0.% | 26.10% | 17.40% | 43.50% | |

| Moderate Multiple-Goals | 40.00% | 0.00% | 50.00% | 10.00% | |

| High Multiple-Goals | 3.40% | 5.10% | 27.10% | 64.40% | |

| Boys | Mastery-Oriented | 62.50% | 0.00% | 37.50% | 0.00% |

| Approach-Oriented | 0.00% | 56.70% | 13.30% | 30.00% | |

| Moderate Multiple-Goals | 38.50% | 7.70% | 23.10% | 30.80% | |

| High Multiple-Goals | 2.80% | 11.10% | 33.30% | 52.80% | |

| Total | Mastery-Oriented | 57.10% | 0.00% | 42.90% | 0.00% |

| Approach-Oriented | 5.70% | 43.40% | 15.10% | 35.80% | |

| Moderate Multiple-Goals | 39.10% | 4.30% | 34.80% | 21.70% | |

| High Multiple-Goals | 3.20% | 7.40% | 29.50% | 60.00% | |

| Performance | Mastery-Oriented | Approach-Oriented | Moderate Multiple-Goals | High Multiple-Goals | Post hoc Comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Bonferroni | |

| Math | 14.34 (0.81) | 14.69 (0.42) | 11.93 (0.63) | 13.48 (0.32) | App > MM MO = MM = HM |

| Literacy | 12.45 (0.75) | 14.07 (0.71) | 12.02 (0.52) | 11.61 (0.41) | App > HM MO = MM = HM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fiévé, J.; Likhanov, M.; Colé, P.; Régner, I. Achievement Goal Profiles and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Literacy: A Person-Centered Approach in Third Grade Students. J. Intell. 2025, 13, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090108

Fiévé J, Likhanov M, Colé P, Régner I. Achievement Goal Profiles and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Literacy: A Person-Centered Approach in Third Grade Students. Journal of Intelligence. 2025; 13(9):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090108

Chicago/Turabian StyleFiévé, Justine, Maxim Likhanov, Pascale Colé, and Isabelle Régner. 2025. "Achievement Goal Profiles and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Literacy: A Person-Centered Approach in Third Grade Students" Journal of Intelligence 13, no. 9: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090108

APA StyleFiévé, J., Likhanov, M., Colé, P., & Régner, I. (2025). Achievement Goal Profiles and Academic Performance in Mathematics and Literacy: A Person-Centered Approach in Third Grade Students. Journal of Intelligence, 13(9), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence13090108