Effects of Physical Exercise Input on the Exercise Adherence of College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Sports Emotional Intelligence and Exercise Self-Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Physical Exercise Input Scale

2.2.2. Exercise Adherence Scale

2.2.3. Sports Emotional Intelligence Scale

2.2.4. Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

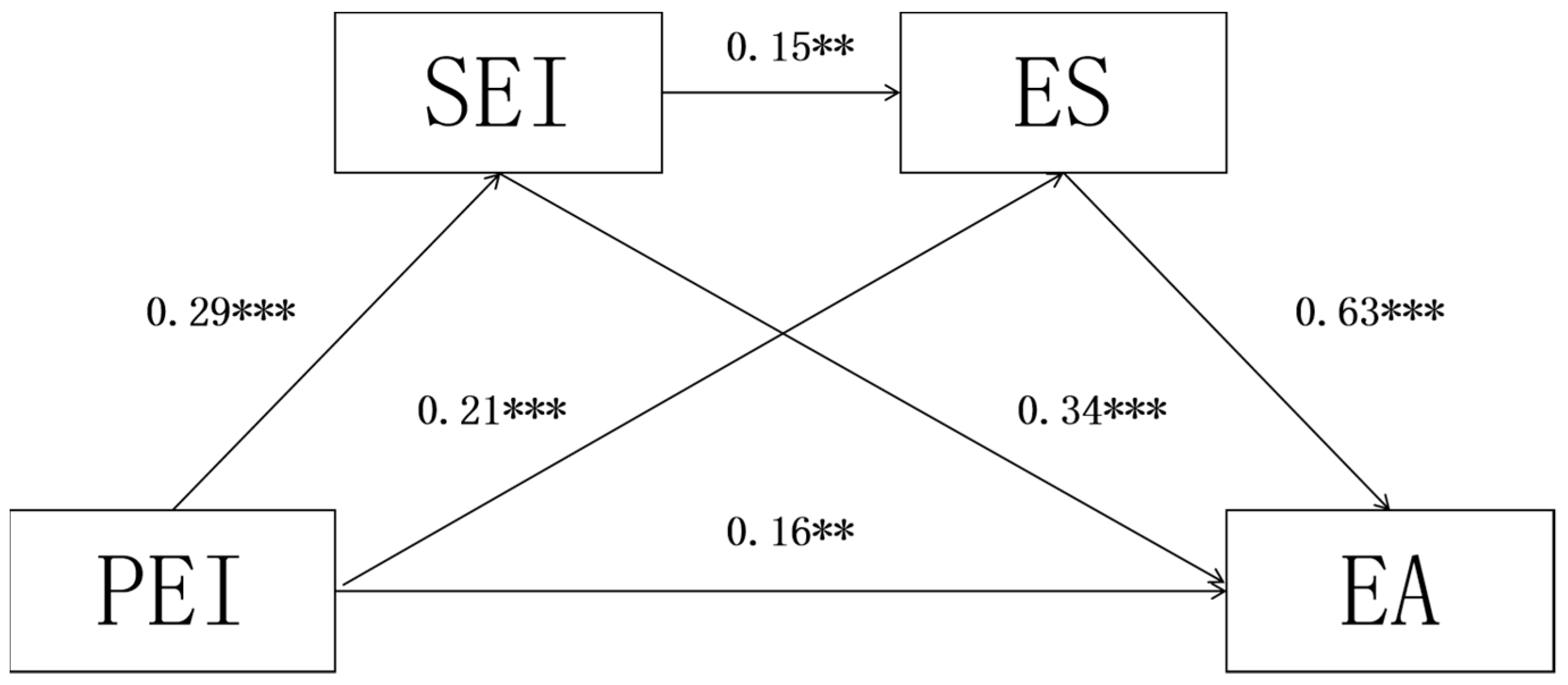

3.3. The Relationship between Physical Exercise Input and Exercise Adherence: A Chain Mediation Effect Test

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effect of Physical Activity Input on Exercise Adherence

4.2. Separate Mediating Roles of Emotional Intelligence and Sport Self-Efficacy

4.3. Chain Mediation of Motor Emotional Intelligence and Motor Self-Efficacy

5. Limitations

6. Implication

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Tammemi, Ala’A. B., Amal Akour, and Laith Alfalah. 2020. Is it just about physical health? An online cross-sectional study exploring the psychological distress among university students in Jordan in the midst of COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 562213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annesi, James J., and Sara M. Powell. 2023. The role of change in self-efficacy in maintaining exercise-associated improvements in mood beyond the initial 6 months of expected weight loss in women with obesity. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 14: 156–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Edwin A. 1997. Self Efficacy the Exercise of Control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bañoset, Raúl F., Juan Jos Calleja-Núez, Roberto Espinoza-Gutirrez, and Antonio Granero-Gallegos. 2023. Mediation of academic self-efficacy between emotional intelligence and academic engagement in physical education undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1178500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Epel, Orna, and Giora Kaplan. 2001. General subjective health status or age-related subjective health status: Does it make a difference? Social Science & Medicine 53: 1373–81. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp, Mark R., Kaitlin L. Crawford, and Ben Jackson. 2019. Social cognitive theory and physical activity: Mechanisms of behaviour change, critique, and legacy. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 42: 110–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, Won-cheol, Song Jin-seop, and Yoon Won-jung. 2019. The Effect of Exercise Immersion on Psychological Satisfaction and Continuation of Exercise in Sports. The Korean Journal of Sport 17: 217–31. [Google Scholar]

- Burnet, Kathryn, Simon Higgins, Elizabeth Kelsch, Justin B. Moore, and Lee Stoner. 2020. The effects of manipulation of Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type (FITT) on exercise adherence: A meta-analysis. Translational Sports Medicine 3: 222–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hongxin, Xulong Li, Hui Yang, and Fugao Jiang. 2022. Characteristics and relationships of exercise motivation and social adaptation of junior high school students in different school football reserve training modes: The mediating role of exercise adherence. China Sports Science and Technology 58: 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, Bryce T., Ashton E. Human, Kaitlin M. Gallagher, and Erin K. Howie. 2021. Relationships between grit, physical activity, and academic success in university students: Domains of physical activity matter. Journal of American College Health 12: 1897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Baolin. 2017. Physical activity input of college students in China: Measurement, antecedents and after-effects. Journal of Tianjin Sports Institute 32: 176–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Baolin, and Lijuan Mao. 2018. The effects of exercise input, exercise commitment and subjective experience on college students’ exercise habits: A mixed model. Journal of Tianjin Sports Institute 33: 492–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Mingyuan, Dachao Zhang, and Min Li. 2022. The construction of action programmes to promote college students’ sports participation in universities in developed countries and the inspiration. Journal of Shenyang Sports Institute 41: 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, Jennifer Schaal, and Jacquelyn L. Banasik. 2001. Exercise self-efficacy. Clinical Excellence for Nurse Practitioners: The International Journal of NPACE 5: 134–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. 2011. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist 56: 218–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Wensheng, Yan Li, Yajun Liu, Dan Li, Gang Wang, Yongsen Liu, Tingran Zhang, and Yunfeng Zheng. 2023. The influence of different physical exercise amounts on learning burnout in adolescents: The mediating effect of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1089570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, Felipe, Virginia Wright, Patricia J. Manns, and Lesley Pritchard. 2021. Is Physical Activity-Related Self-Efficacy Associated with Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour among Ambulatory Children with Cerebral Palsy? Physiotherapy Canada 74: 151–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Yuanyuan, Yao Li, Dawei Cao, and Lianzhong Cao. 2021. A study on the influence of coaches’ leadership behaviour on athletes’ sports input—The mediating effect of coach-athlete relationship. Journal of Shenyang Sports Institute 40: 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Garn, Alex C., and Kelly L. Simonton. 2022. Motivation beliefs, emotions, leisure time physical activity, and sedentary behavior in university students: A full longitudinal model of mediation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 58: 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Agustín Ernesto Martínez, José Antonio Piqueras, and Victoriano Ramos Linares. 2010. Emotional intelligence in physical and mental health. Electronic Journal of Research in Education Psychology 8: 861–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gordan, MMarzieh, and Isai Amutan Krishanan. 2014. A review of BF Skinner’s ‘Reinforcement Theory of Motivation’. International Journal of Research in Education Methodology 5: 680–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, Martin S., and Kyra Hamilton. 2021. Effects of socio-structural variables in the theory of planned behaviour: A mediation model in multiple samples and behaviours. Psychology & Health 36: 307–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Xiaoliang, and Yunyun Yang. 2022. Healthy physical education curriculum model and students’ extracurricular sports participation—Test based on the trans-contextual model of motivation. BMC Public Health 22: 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Binbin, Lejing Yan, Kuiyong Zuo, Xiangying Wang, and Yujun Chen. 2022. The effects of cumulative situational risk on college students’ exercise adherence: The chain-mediated roles of cognitive reappraisal and exercise behavioural intention. Journal of Shandong Institute of Physical Education 38: 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Xiaobing, and Xinran Liu. 2011. A review of research on emotions in sports. Journal of Shandong Institute of Physical Education 27: 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Inhyung, Kim. 2022. The Mediating Effects of Exercise Emotion between Passion and Sport Commitment of Middle Schooler Participating in School Sports Club. The Korean Journal of Physical Education 61: 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jakicic, John M., and Amy D. Otto. 2005. Physical activity considerations for the treatment and prevention of obesity. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 82: 226S–9S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javelle, Florian, Anke Vogel, Sylvain Laborde, Max Oberste, Matthew Watson, and Philipp Zimmer. 2023. Physical exercise is tied to emotion-related impulsivity: Insights from correlational analyses in healthy humans. European Journal of Sport Science 23: 1010–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Yuan, Liwei Zhang, and Zhixiong Mao. 2018. Physical exercise and mental health: The role of emotion regulation self-efficacy and emotion regulation strategies. Psychological and Behavioural Research 16: 570–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Dae-geun, Na-young Choo, and Ssong-hyun Cho. 2018. A study on the Effects of Commitment and Passion towards Exercise of Middle School Students Participating in School Sports Club Activities on Exercise Emotion and Continuance. Teacher Education Research 57: 517–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Rodney P., Kathryn E. Royse, Tanya J. Benitez, and Dorothy W. Pekmezi. 2014. Physical activity and quality of life among university students: Exploring self-efficacy, self-esteem, and affect as potential mediators. Quality of Life Research 23: 659–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaee-Pool, M., R. Sadeghi, F. Majlessi, and A. Rahimi Foroushani. 2015. Effects of physical exercise programme on happiness among older people. Journal of Psychiatric And mental Health Nursing 22: 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Woo-Cheol. 2015. Influence of exercise self efficacy and perceived health status according to the stage of change for exercise behaviours in older adults. Journal of Digital Convergence 13: 549–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yong-Doo. 2021. The Effects of Self-Efficacy Perceived by Student Golf Players on Exercise Commitment and Emotion. Journal of Wellness 16: 241–46. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, Sylvain, Emma Mosley, Stefan Ackermann, Adrijana Mrsic, and Fabrice Dosseville. 2018. Emotional intelligence in sports and physical activity: An intervention focus. Emotional Intelligence in Education: Integrating Research with Practice 2018: 289–320. [Google Scholar]

- Laborde, Sylvain, Fabrice Dosseville, and Mark S. Allen. 2016. Emotional intelligence in sport and exercise: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 26: 862–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, Carl J., Cemal Ozemek, Salvatore Carbone, Peter T. Katzmarzyk, and Steven N. Blair. 2019. Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circulation Research 124: 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Myung-chan, and Byung-il Moon. 2017. The Relationship between Exercise Passion, Exercise Commitment and Exercise Duration in Wushu. The Korean Journal of Sport 15: 703–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ji-hwan, and Tai-Hyung Kim. 2016. The Effect of Fun Factor of University Golf Class on Satisfaction of Class and Exercise Adherence. The Korean Society of Sports Science 25: 677–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seung Do. 2020. The Effect of Golf Participation on Exercise Adherence through Exercise Immersion. Journal of KOEN 14: 103–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yang-Joo, Ah-Ram Kim, and Keun-Ok An. 2015. Participation Level, Rating of Perceived Exertion, Exercise Commitment and Exercise Adherence of Marathon Participation. Kinesiology 17: 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ye Hoon, K. Andrew R. Richards, and Nicholas S. Washhburn. 2020. Emotional intelligence, job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion, and subjective well-being in high school athletic directors. Psychological Reports 123: 2418–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levillain, Guillaume, Guillaume Martinent, Philippe Vacher, and Michel Nicolas. 2022. Longitudinal trajectories of emotions among athletes in sports competitions: Does emotional intelligence matter? Psychology of Sport and Exercise 58: 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jinglv, Jiangtao Ma, Shuwang Li, and Zhenning Li. 2020. Relationships among motivation, sport input, participation satisfaction and intention to continue participation in mass ice and snow sports in the context of the Beijing Winter Olympics. Journal of Chengdu Institute of Physical Education 46: 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Wenliang, and Ti Hu. 2023. Research on the construction of index system to promote the sustainable development of core literacy of physical education teachers in Chinese universities from the perspective of higher education modernization. Sustainability 15: 13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Chiung-ju, and Nancy K. Latham. 2009. Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD002759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Ling. 2022. The practice of psychological well-being education model for poor university students from the perspective of positive psychology. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 951668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, Edward, Gerald J. Jerome, David X. Marquez, Steriani Elavsky, and Bryan Blissmer. 2003. Exercise self-efficacy in older adults: Social, affective, and behavioral influences. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 25: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Yun, Kexin Cheng, Jianping Liu, and Baojuan Ye. 2019. The effect of emotional intelligence on entrepreneurial intention of college students: The chain mediating role of achievement motivation and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Psychology Exploration 39: 173–78. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa-Chamari, Imen, Abdulaziz Farooq, Mohamed Romdhani, Jad Adrian Washif, Ummukulthoum Bakare, Mai Helmy, Ramzi Al-horani, Paul Salamh, Nicolas Robin, and Olivier Hue. 2024. The relationship between quality of life, sleep quality, mental health, and physical activity in an international sample of college students: A structural equation modeling approach. Frontiers in Public Health 12: 1397924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, Michael, Anne K. Reimers, and Yolanda Demetriou. 2021. Leisure time sports activities and life satisfaction: Deeper insights based on a representative survey from Germany. Applied Research in Quality of Life 16: 2155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Jonathan, Paul McAuley, Carl J. Lavie, Jean-Pierre Despres, Ross Arena, and Peter Kokkinos. 2015. Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as major markers of cardiovascular risk: Their independent and interwoven importance to health status. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 57: 306–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neace, Savannah M., Allison M. Hicks, Marci S. DeCaro, and Paul G. Salmon. 2022. Trait mindfulness and intrinsic exercise motivation uniquely contribute to exercise self-efficacy. Journal of American College Health 70: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, Melissa C., Mary Story, Nicole I. Larson, Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, and Leslie A. Lytle. 2008. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: An overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity 16: 2205–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupert, Shevaun D., Margie E. Lachman, and Stacey B. Whitbourne. 2009. Exercise self-efficacy and control beliefs: Effects on exercise behavior after an exercise intervention for older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 17: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, Patricia S., Márcia Gonçalves Ferreira, Paulo Rogério Melo Rodrigues, Ana Paula Muraro, Lídia Pitaluga Pereira, and Rosangela Alves Pereira. 2018. Longitudinal Study on the Lifestyle and Health of University Students (ELESEU): Design, methodological procedures, and preliminary results. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 34: e00145917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. W., R. Park, and Y. H. Yoo. 2021. Effect of Taekwondo Demonstration Team’s Exercise Commitment on Psychological Well-being and Exercise Continuity. Journal of Coaching Development 23: 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penedo, Frank J., and Jason R. Dahn. 2005. Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 18: 189–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, Justy, and Sarah Buck. 2009. The effect of regular aerobic exercise on positive-activated affect: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 10: 581–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Filipe, Diogo S. Teixeira, Henrique P. Neiva, Luís Cid, and Diogo Monteiro. 2020. Understanding exercise adherence: The predictability of past experience and motivational determinants. Brain Sciences 10: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenaar-Golan, Vered, Ofra Walter, Zeev Greenberg, and Alexander Zibenberg. 2020. Emotional intelligence in higher education: Exploring its effects on academic self-efficacy and coping with stress. College Student Journal 54: 443–59. [Google Scholar]

- So, Young-ho. 2019. Relationship among Emotional Intelligence Exercise Passion and Sport Commitment of High School Athletes. Korean Journal of Physical Education 58: 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Yan-liqing, and Tian-feng Zhang. 2022. Construction of system and guarantee of path for sports to promote comprehensive development of college students. Sports Culture Guide 3: 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulou, Georgia, Mark B. Powers, Angela C. Berry, Jasper A. J. Smits, and Michael W. Otto. 2006. Exercise interventions for mental health: A quantitative and qualitative review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 13: 179–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, Mark S., Allana G. LeBlanc, Michelle E. Kho, Travis J. Saunders, Richard Larouche, Rachel C. Colley, Gary Goldfield, and Sarah C. Gorber. 2011. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 8: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayar, Shagini, Marina Fiori, and Elise Bausseron. 2020. Emotional intelligence and performance in a stressful task: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Personality and Individual Differences 156: 109790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hong-mei, Qi Zhang, and Zhi-nan Huang. 2019. An empirical study of learning behavioural input and cognitive input in open learning environments. Modern Education Technology 29: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Kun, Ying Yang, Tingran Zhang, Yiyi Ouyang, Bin Liu, and Jiong Luo. 2020. The relationship between physical activity and emotional intelligence in college students: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, Darren E. R., Crystal Whitney Nicol, and Shannon S. D. Bredin. 2006. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ 174: 801–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedenman, Eric M., Aaron J. Kruse-Diehr, Matthew R. Bice, Justin McDaniel, Juliane P. Wallace, and Julie A. Partridge. 2023. The role of sport participation on exercise self-efficacy, psychological need satisfaction, and resilience among college freshmen. Journal of American College Health 12: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Qionghua. 2019. Emotional ABC theory and the psychological art of leading cadres talking with subordinates. Leadership Science 22: 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jingtao, Xinjuan Zhao, Wennan Zhao, Xiaodan Chi, Jinglan Ji, and Jun Hu. 2022. Effects of physical exercise on negative emotions in college students: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology 30: 930–34. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Tong-Yao, and La-Mei Liu. 2022. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between hope level and rehabilitation exercise adherence among stroke patients with hemiplegia. Acta Medica Mediterranea 38: 759–465. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Shi, Mengdi Li, Shangbing Li, and Shouzhong Zhang. 2019. The relationship between transactional leadership behaviour and college students’ willingness to adhere to physical activity: Chain mediation of exercise self-efficacy and physical education class satisfaction. Journal of Shenyang Sports Institute 38: 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Xiao-jian, Jian-quiang Du, Liu Ji, Jian-ping Xiong, and Cheng-ye Ji. 2012. A study on the trend of physical fitness of Chinese college students. Journal of Beijing Sport University 35: 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Jin. 2010. Exploring the Sport Emotional Intelligence Model and Measurement. Korean Journal of Sport Psychology 21: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jia, Donghuan Bai, Long Qin, and Pengwei Song. 2022. The development of the Chinese version of the Sports Emotional Intelligence Scale. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1068862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ge, Wanxuan Feng, Liangyu Zhao, Xiuhan Zhao, and Tuojian Li. 2024a. The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. Scientific Reports 14: 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Li, Donghuan Bai, Pengwei Song, and Jia Zhang. 2024b. Effects of physical health beliefs on college students’ physical exercise behavior intention: Mediating effects of exercise imagery. BMC Psychology 12: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Mimhnan, Bing Qi, and Chunlin Ge. 2016. The predictive role of emotional intelligence on sports performance in tennis players. Journal of Xi’an Institute of Physical Education and Sports 33: 119–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Leqing, and Baolin Dong. 2016. Subjective experience, commitment and exercise adherence: A case of duality and undifferentiation. Journal of Nanjing Institute of Physical Education(Social Science Edition) 30: 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Na, Yao Shang, and Qingran Wang. 2024. The relationship between exercise atmosphere, flow experience, and subjective well-being in middle school students: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 103: e38987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Yuxin, Shijie Liu, Shuangshuang Guo, Qiuhao Zhao, and Yujun Cai. 2023. Peer Support and Exercise Adherence in Adolescents: The Chain-Mediated Effects of Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulation. Children 10: 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | M | SD | PEI | SEI | ES | EA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEI | 3.83 | 0.54 | 1 | |||

| SEI | 3.85 | 0.59 | 0.55 ** | 1 | ||

| ES | 3.45 | 0.53 | 0.40 ** | 0.47 ** | 1 | |

| EA | 3.80 | 0.47 | 0.35 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.19 ** | 1 |

| Regression Equation | Overall Fit | Significance of Regression Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Predictor Variable | R2 | F | β | t |

| SEI | PEI | 0.35 | 14.54 | 0.29 | 5.78 *** |

| ES | PEI | 0.38 | 15.81 | 0.21 | 5.32 *** |

| SEI | 0.15 | 4.55 ** | |||

| EA | PEI | 0.36 | 14.89 | 0.16 | 4.96 ** |

| SEI | 0.34 | 5.75 *** | |||

| ES | 0.63 | 6.89 *** | |||

| Path | Point Estimate | Product of Coefficients | 5000 Bootstrap 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias Corrected | Percentile | |||||||

| S.E | Z | P | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||

| PEI→SEI→EA | 0.10 | 0.03 | 5.98 | 0.000 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

| PEI→ES→EA | 0.13 | 0.01 | 2.64 | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| PEI→SEI→ES→EA | 0.09 | 0.01 | 2.80 | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Total effect | 0.32 | 0.04 | 5.36 | 0.000 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, D.; Pan, J.; Ran, F.; Bai, D.; Zhang, J. Effects of Physical Exercise Input on the Exercise Adherence of College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Sports Emotional Intelligence and Exercise Self-Efficacy. J. Intell. 2024, 12, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12100094

An D, Pan J, Ran F, Bai D, Zhang J. Effects of Physical Exercise Input on the Exercise Adherence of College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Sports Emotional Intelligence and Exercise Self-Efficacy. Journal of Intelligence. 2024; 12(10):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12100094

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Dongzhen, Jianhua Pan, Feng Ran, Donghuan Bai, and Jia Zhang. 2024. "Effects of Physical Exercise Input on the Exercise Adherence of College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Sports Emotional Intelligence and Exercise Self-Efficacy" Journal of Intelligence 12, no. 10: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12100094

APA StyleAn, D., Pan, J., Ran, F., Bai, D., & Zhang, J. (2024). Effects of Physical Exercise Input on the Exercise Adherence of College Students: The Chain Mediating Role of Sports Emotional Intelligence and Exercise Self-Efficacy. Journal of Intelligence, 12(10), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12100094