Tell Us What You Really Think: A Think Aloud Protocol Analysis of the Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test

1.2. Think-Aloud Protocol Analysis

1.3. The Current Research

2. Study 1

2.1. Method

2.2. Procedure and Materials

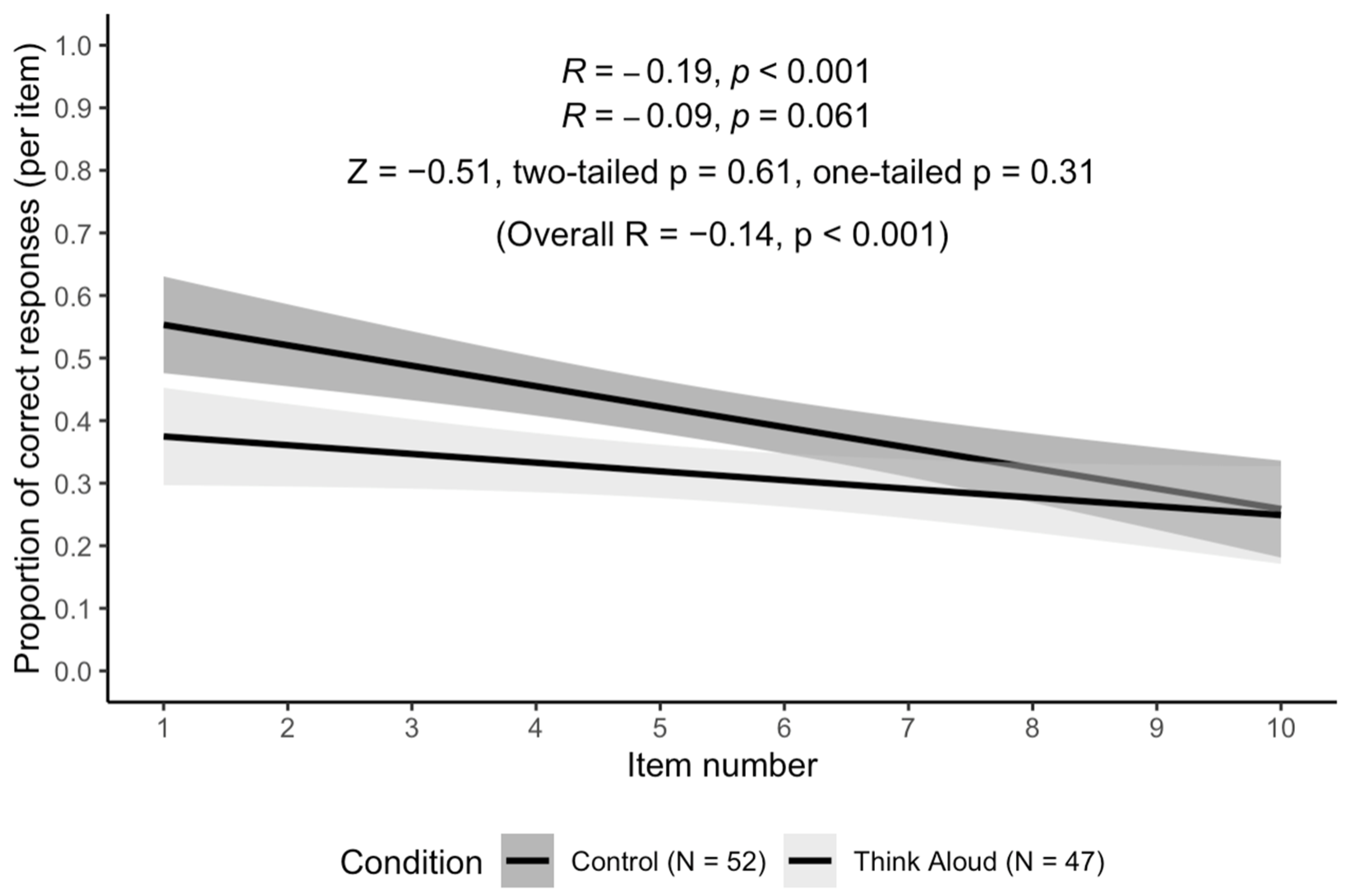

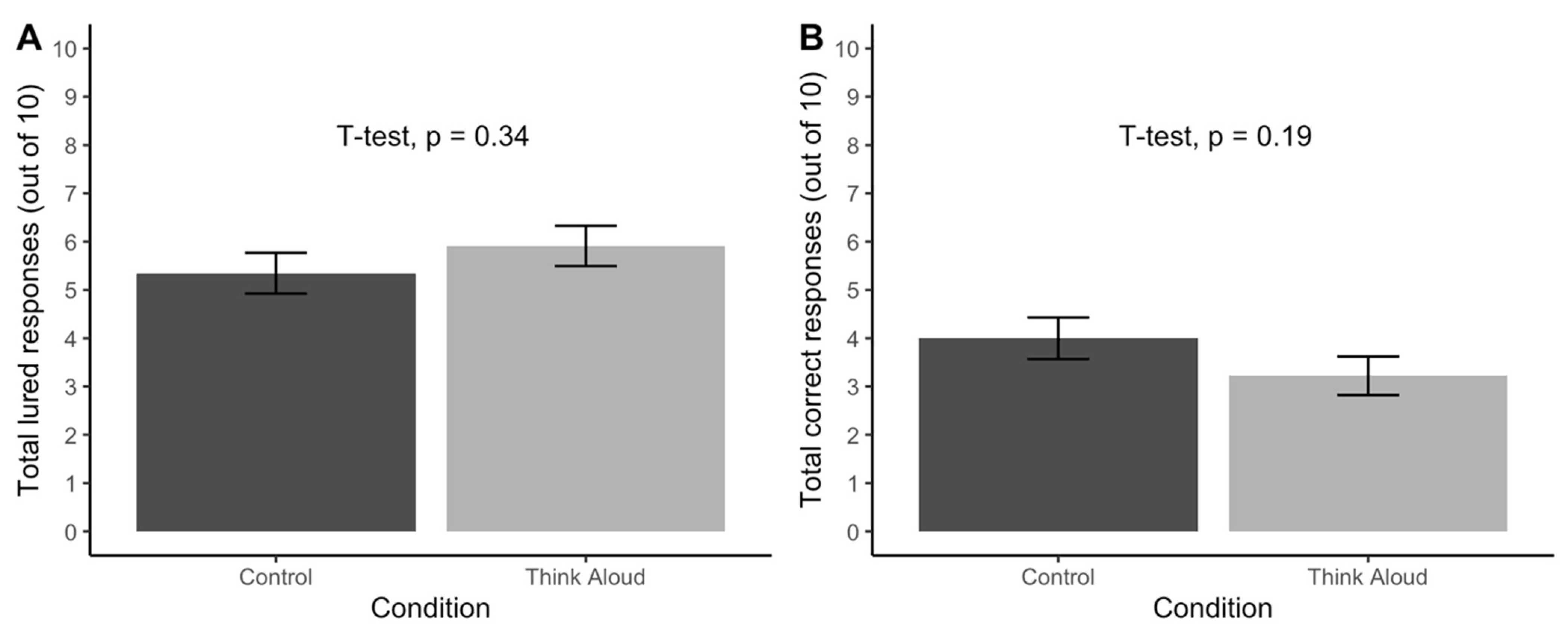

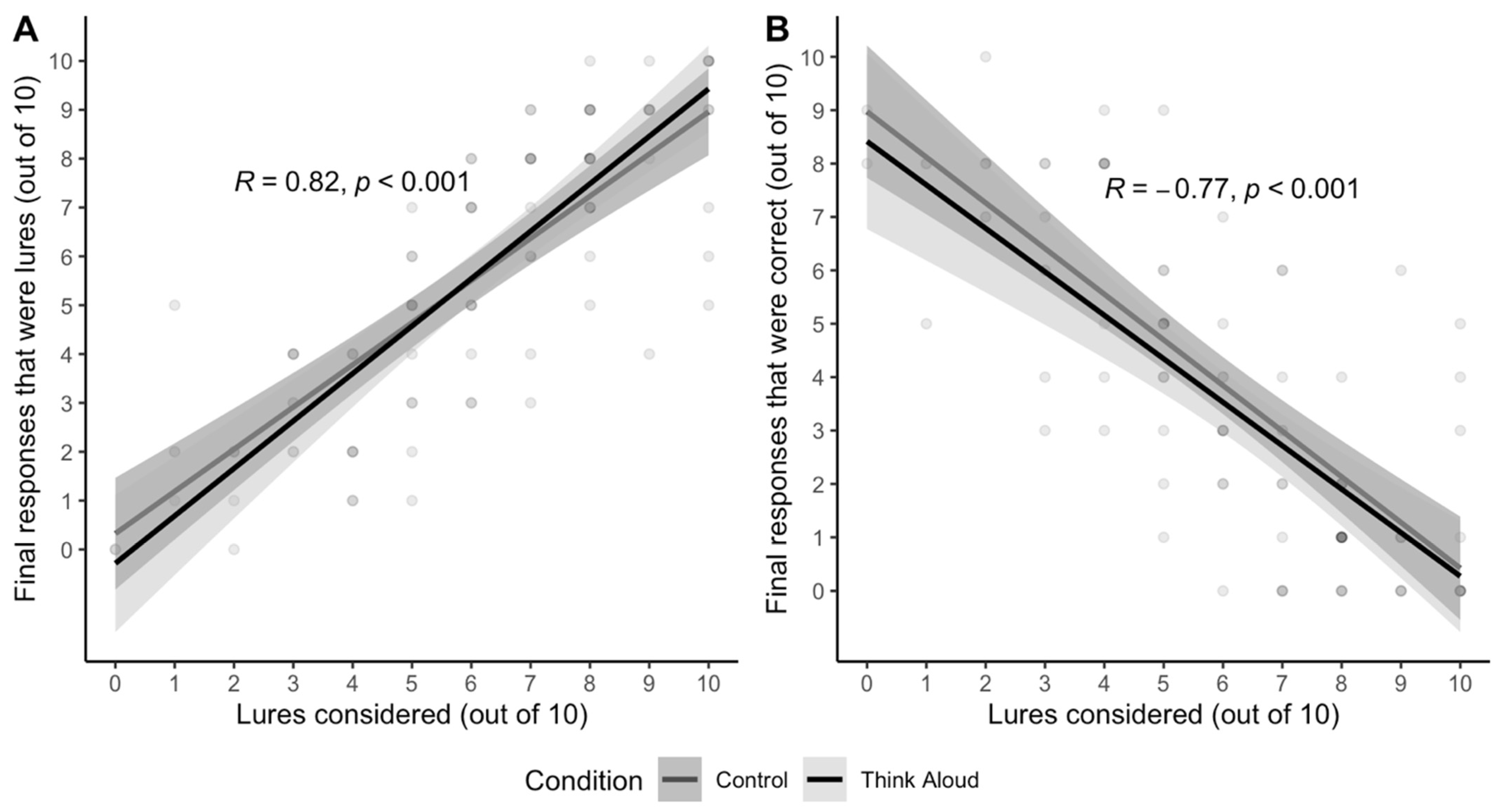

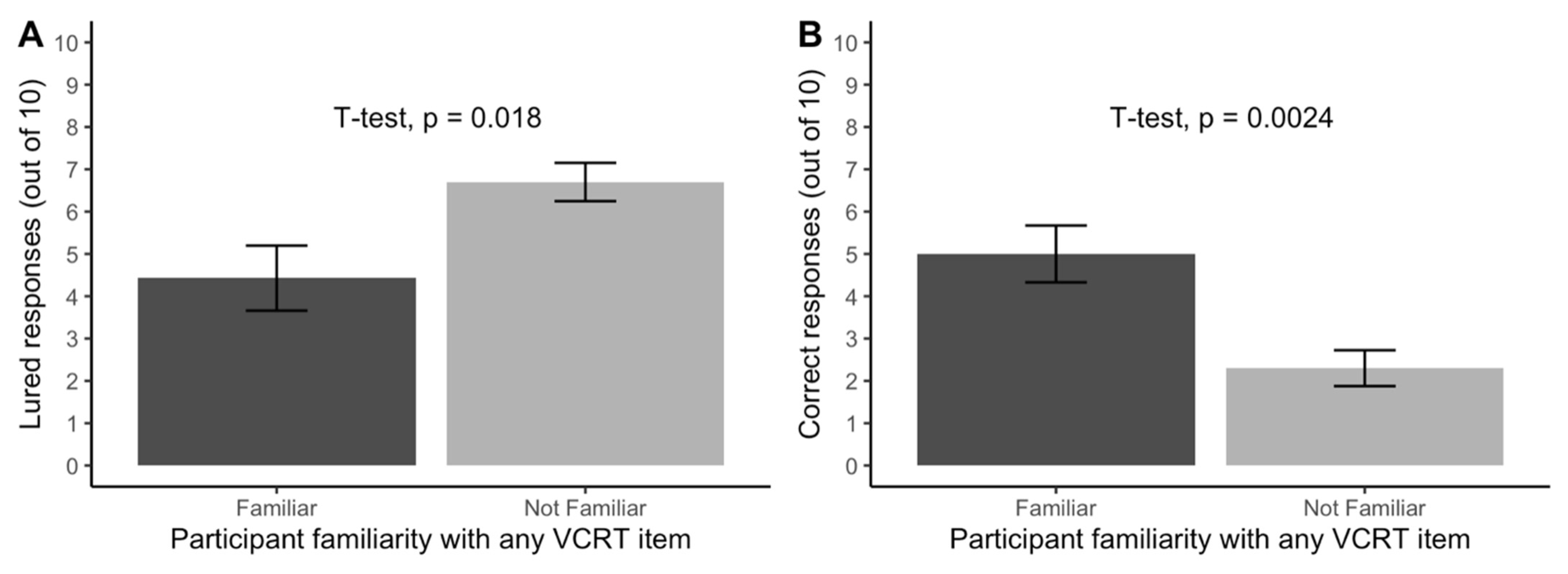

2.3. Results

2.4. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Method

3.2. Procedure and Materials

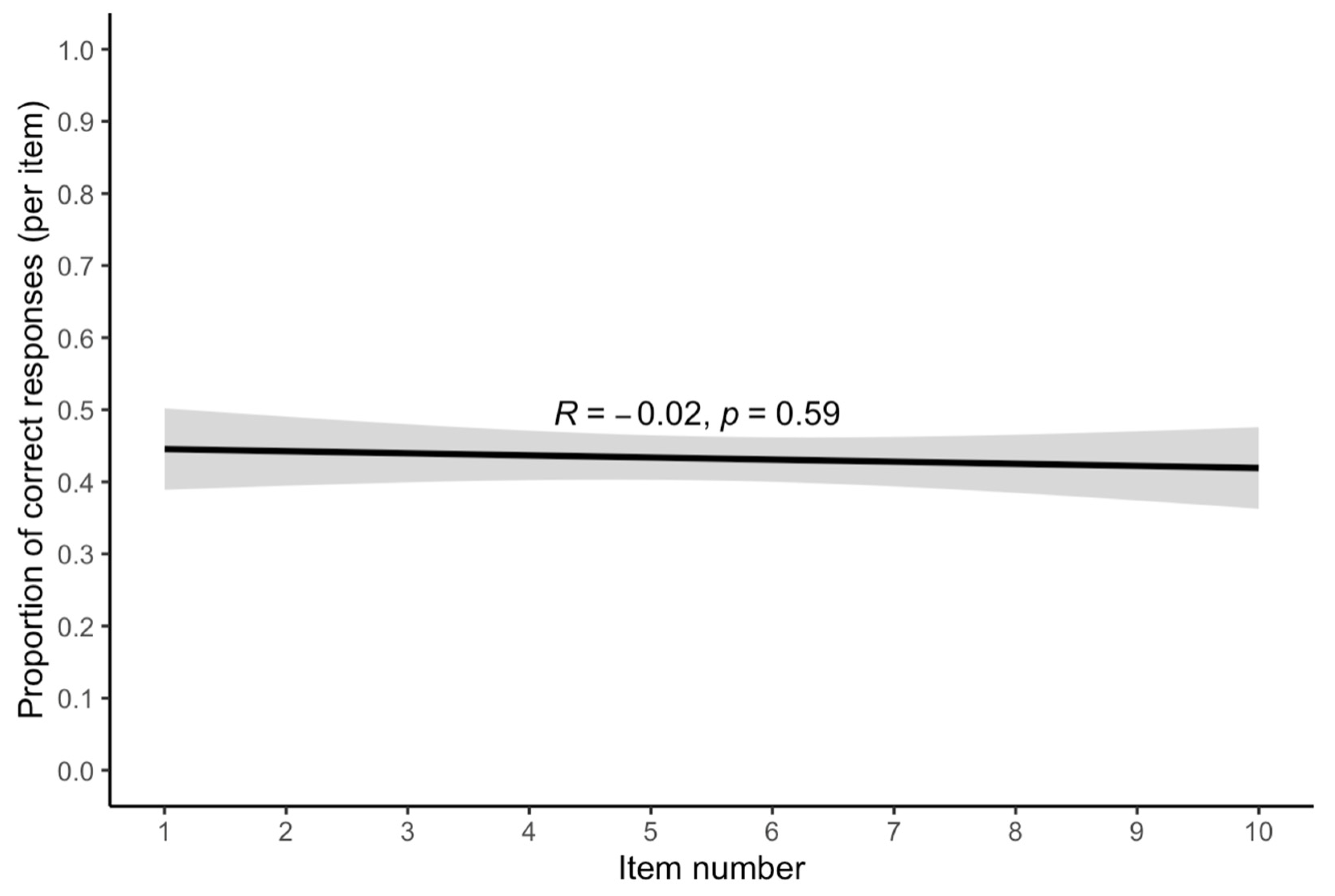

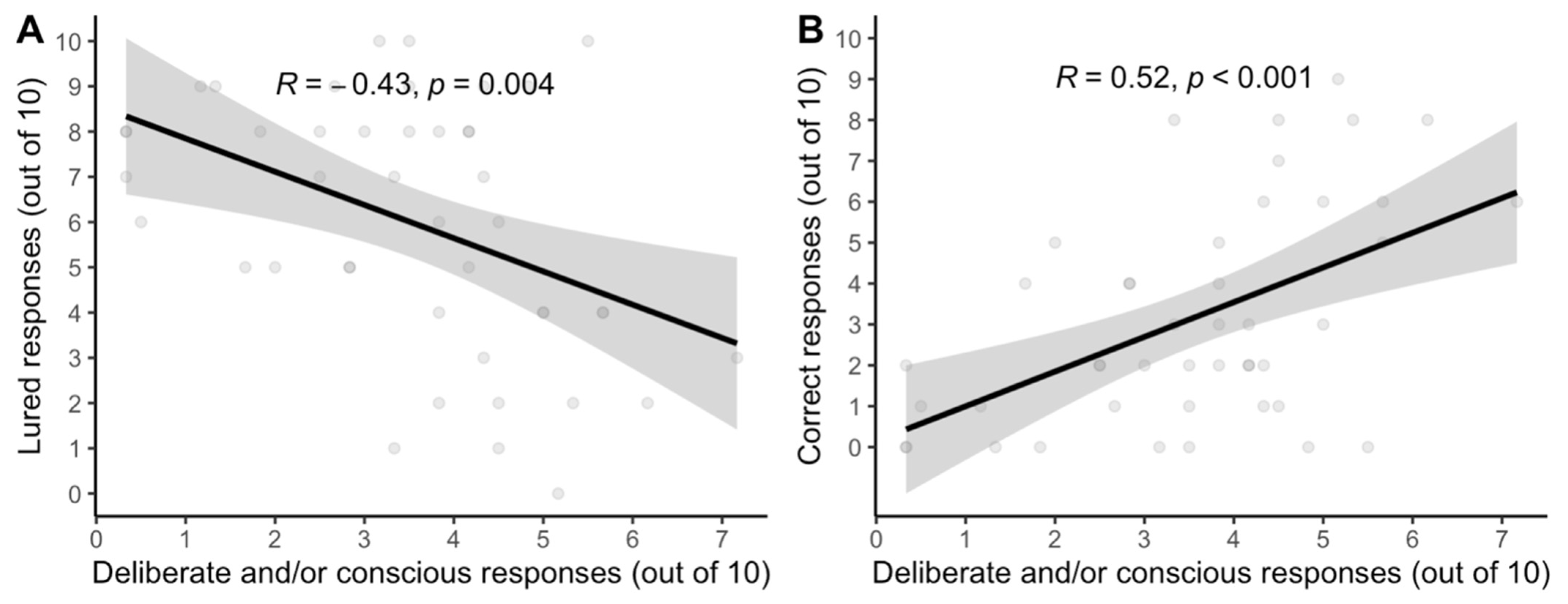

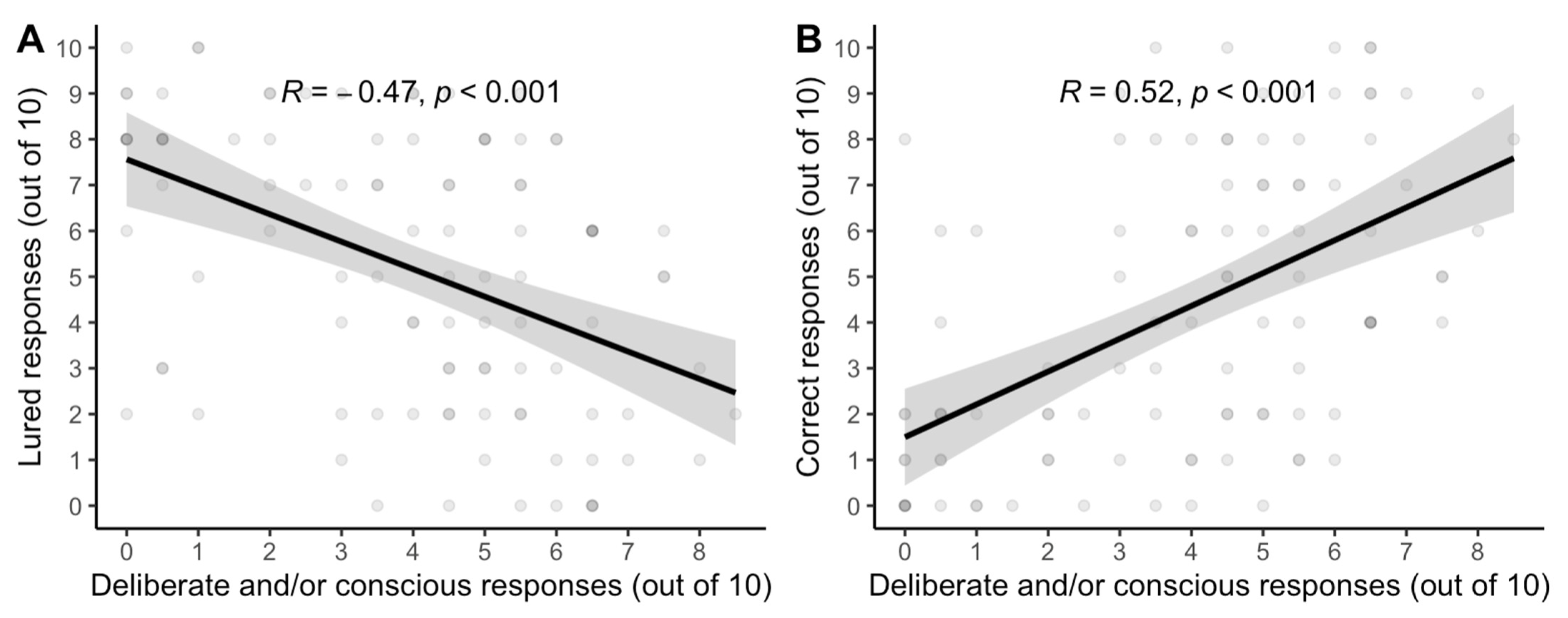

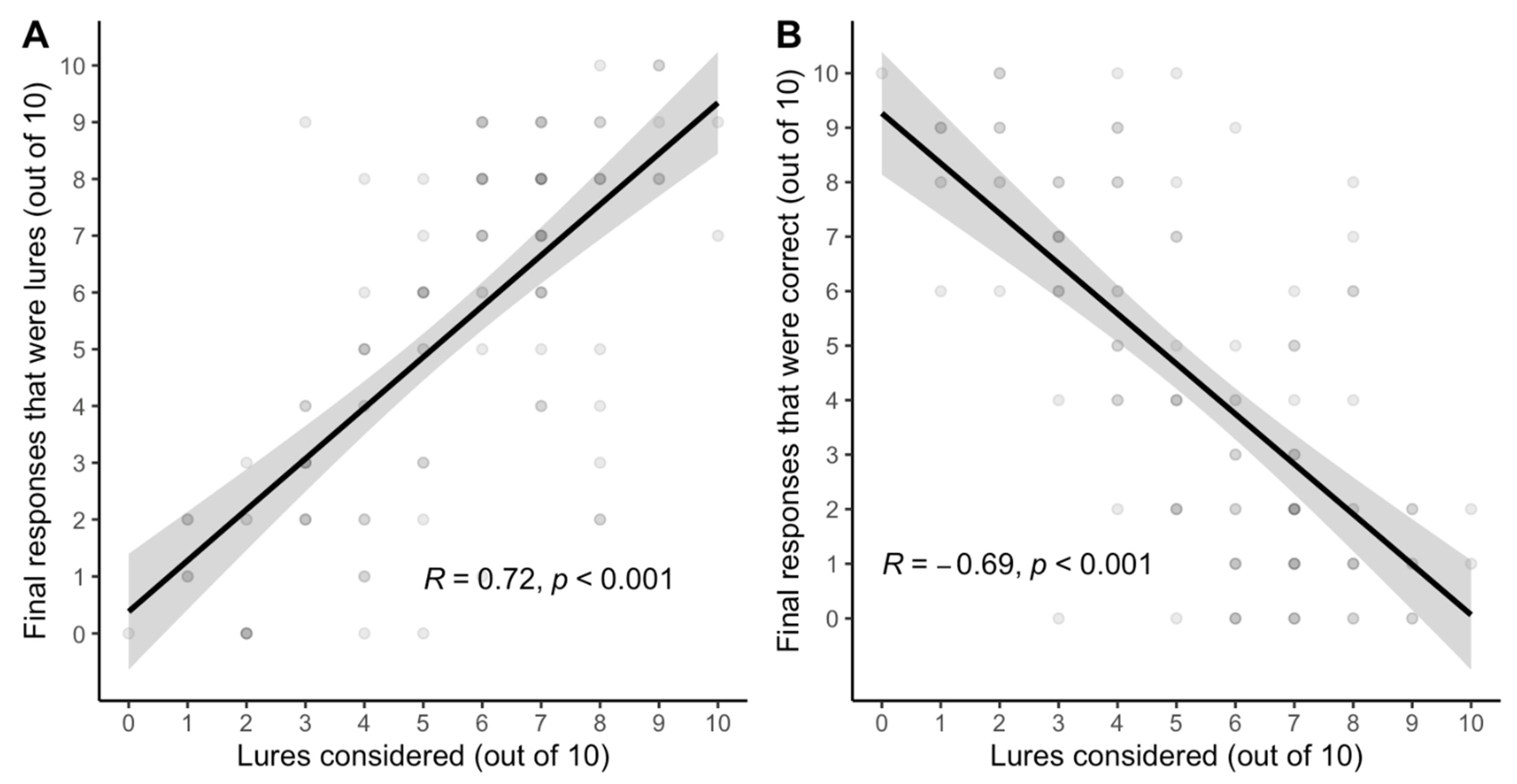

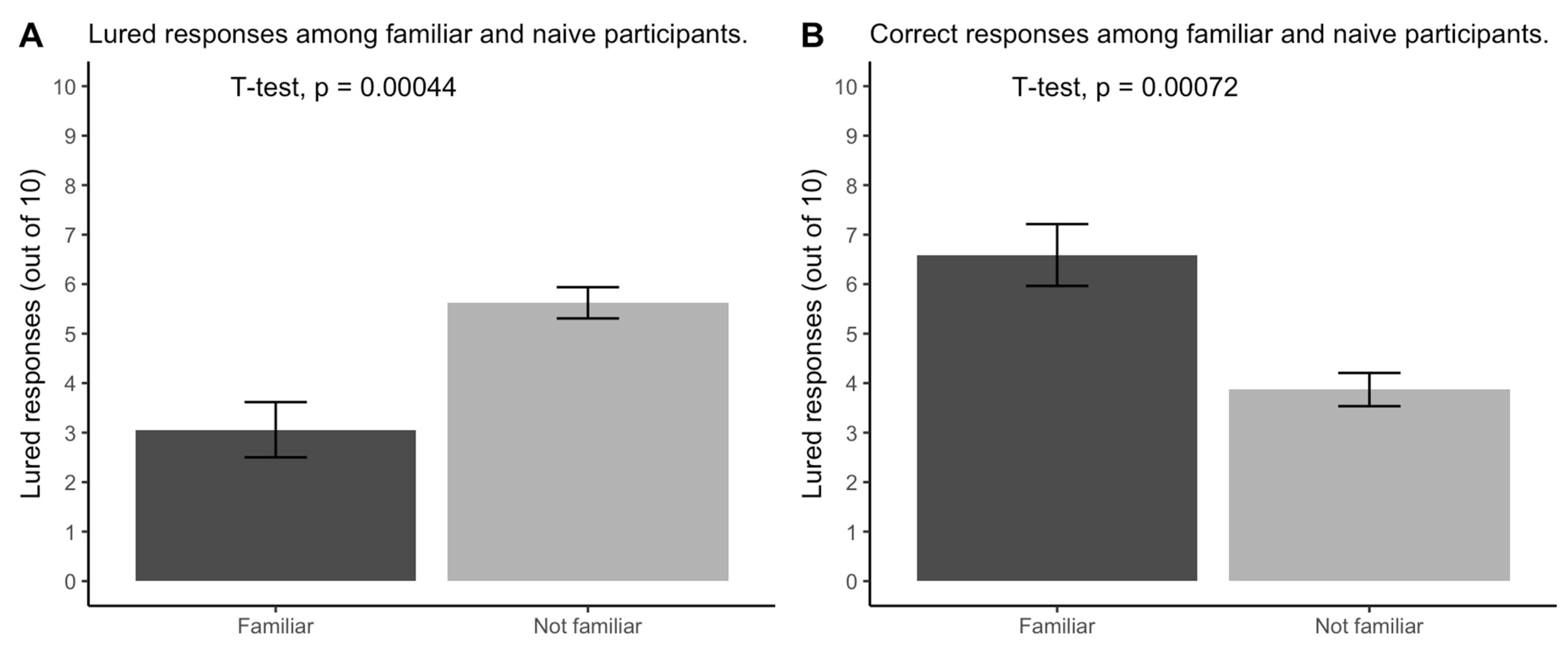

3.3. Results

4. General Discussion

4.1. Methodological Implications

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- Mary’s father has 5 daughters but no sons—Nana, Nene, Nini, Nono. What is the fifth daughter’s name probably?[correct answer: Mary, lured answer: Nunu][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘Nunu’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- (2)

- If you were running a race, and you passed the person in 2nd place, what place would you be in now?[correct answer: 2nd, lured answer: 1st][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘1st’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- (3)

- It’s a stormy night and a plane takes off from JFK airport in New York. The storm worsens, and the plane crashes-half lands in the United States, the other half lands in Canada. In which country do you bury the survivors?[correct answer: don’t bury survivors, lured answers: answers about burial location][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that survivor burial was an option?”Yes No

- (4)

- A monkey, a squirrel, and a bird are racing to the top of a coconut tree. Who will get the banana first, the monkey, the squirrel, or the bird?[correct answer: no banana on coconut tree, lured answer: any of the animals][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘bird’, ‘squirrel’, or ‘monkey’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- (5)

- In a one-storey pink house, there was a pink person, a pink cat, a pink fish, a pink computer, a pink chair, a pink table, a pink telephone, a pink shower—everything was pink! What colour were the stairs probably?[correct answer: a one-storey house probably doesn’t have stairs, lured answer: pink][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘pink’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- (6)

- How many of each animal did Moses put on the ark?[correct answer: none; lured answer: two][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘two’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- (7)

- The wind blows west. An electric train runs east. In which cardinal direction does the smoke from the locomotive blow?[correct answer: no smoke from an electric train, lured answer: west][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point the locomotive will produce smoke?”Yes No

- (8)

- If you have only one match and you walk into a dark room where there is an oil lamp, a newspaper and wood—which thing would you light first?[correct answer: match, lured answer: oil lamp][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘oil lamp’, ‘newspaper’, or ‘wood’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- (9)

- Would it be ethical for a man to marry the sister of his widow?[correct answer: not possible, lured answer: yes, no][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that it is possible for a man to marry the sister of his widow?”Yes No

- (10)

- Which sentence is correct: (a) “the yolk of the egg are white” or (b) “the yolk of the egg is white”?[correct answer: the yolk is yellow, lured answer: b][Page break]“Do you remember thinking at any point that ‘a’ or ‘b’ could be the answer?”Yes No

- Conditions: Control condition = 0. Think Aloud condition = 1.

- Standard coding: Sum correct and lured answers for reflective and unreflective parameters, respectively.

- From transcripts of think-aloud condition, create variables for (a) whether each participant reconsidered each their initial responses, (b) whether each participant verbalized any reason(s) for or against any response(s), and (c) whether a participant mentioned being familiar with any verbal reflection test question.

References

- Attali, Yigal, and Maya Bar-Hillel. 2020. The False Allure of Fast Lures. Judgment and Decision Making 15: 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, Bence, and Wim De Neys. 2019. The Smart System 1: Evidence for the Intuitive Nature of Correct Responding on the Bat-and-Ball Problem. Thinking & Reasoning 25: 257–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Linden J., and Alexandra Stevens. 2009. Evidence for a Verbally-Based Analytic Component to Insight Problem Solving. Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society 31: 1060–65. [Google Scholar]

- Białek, Michał, and Gordon Pennycook. 2018. The Cognitive Reflection Test Is Robust to Multiple Exposures. Behavior Research Methods 50: 1953–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blech, Christine, Robert Gaschler, and Merim Bilalić. 2020. Why Do People Fail to See Simple Solutions? Using Think-Aloud Protocols to Uncover the Mechanism behind the Einstellung (Mental Set) Effect. Thinking & Reasoning 26: 552–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burič, Roman, and Jakub Šrol. 2020. Individual Differences in Logical Intuitions on Reasoning Problems Presented under Two-Response Paradigm. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 32: 460–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Nick. 2019. What We Can (and Can’t) Infer about Implicit Bias from Debiasing Experiments. Synthese 198: 1427–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Nick. 2022a. A Two-Factor Explication of “Reflection”: Unifying, Making Sense of, and Guiding the Philosophy and Science of Reflective Reasoning. pp. 1–21. Available online: https://researchgate.net/publication/370131881 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Byrd, Nick. 2022b. All Measures Are Not Created Equal: Reflection Test, Think Aloud, and Process Dissociation Protocols. Available online: https://researchgate.net/publication/344207716 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Byrd, Nick. 2022c. Bounded Reflectivism & Epistemic Identity. Metaphilosophy 53: 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Nick. 2022d. Great Minds Do Not Think Alike: Philosophers’ Views Predicted by Reflection, Education, Personality, and Other Demographic Differences. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, Simon, Nick Byrd, and Philipp Chapkovski. 2022. Experiments in Reflective Equilibrium Using the Socrates Platform. Paper presented at Remotely to Reflection on Intelligent Systems: Towards a Cross-Disciplinary Definition, Stuttgart, Germany, October 20–21; Available online: https://researchgate.net/publication/370132037 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Erceg, Nikola, Zvonimir Galic, and Mitja Ružojčić. 2020. A Reflection on Cognitive Reflection—Testing Convergent Validity of Two Versions of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Judgment & Decision Making 15: 741–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K. Anders. 2003. Valid and Non-Reactive Verbalization of Thoughts During Performance of Tasks Towards a Solution to the Central Problems of Introspection as a Source of Scientific Data. Journal of Consciousness Studies 10: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K. Anders, and Herbert A. Simon. 1980. Verbal Reports as Data. Psychological Review 87: 215–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K. Anders, and Herbert A. Simon. 1993. Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data, revised ed. Cambridge: Bradford Books/MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Jonathan. 2007. On the Resolution of Conflict in Dual Process Theories of Reasoning. Thinking & Reasoning 13: 321–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Jonathan, and Keith E. Stanovich. 2013. Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition Advancing the Debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science 8: 223–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, Jonathan, Julie L. Barston, and Paul Pollard. 1983. On the Conflict between Logic and Belief in Syllogistic Reasoning. Memory & Cognition 11: 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Mark C., K. Anders Ericsson, and Ryan Best. 2011. Do Procedures for Verbal Reporting of Thinking Have to Be Reactive? A Meta-Analysis and Recommendations for Best Reporting Methods. Psychological Bulletin 137: 316–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankish, Keith. 2010. Dual-Process and Dual-System Theories of Reasoning. Philosophy Compass 5: 914–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, Shane. 2005. Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making. Journal of Economic Perspectives 19: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebreyesus, Tedros Adhanom. 2020. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 on March 11. Available online: who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Howarth, Stephanie, and Simon Handley. 2016. Belief Bias, Base Rates and Moral Judgment: Re-Evaluating the Default Interventionist Dual Process Account. In Thinking Mind. Edited by Niall Galbraith, Erica Lucas and David Over. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Isler, Ozan, Onurcan Yilmaz, and Burak Dogruyol. 2020. Activating Reflective Thinking with Decision Justification and Debiasing Training. Judgment and Decision Making 15: 926–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Shane Frederick. 2002. Representativeness Revisited: Attribute Substitution in Intuitive Judgment. In Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment. Edited by Thomas Gilovich, Dale W. Griffin and Daniel Kahneman. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J. Richard, and Gary G. Koch. 1977. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 33: 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machery, Edouard. 2021. A Mistaken Confidence in Data. European Journal for Philosophy of Science 11: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, Henry, Pier-Luc de Chantal, Janie Brisson, Éloise Dubé, Valerie Thompson, and Ian Newman. 2021. Reasoning Strategies Predict Use of Very Fast Logical Reasoning. Memory & Cognition 49: 532–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Human Subjects Protection. 2020. Temporary Cessation to Some FSU Human Subjects Research. Florida State University News (blog). March 23. Available online: https://news.fsu.edu/announcements/covid-19/2020/03/23/temporary-cessation-to-some-fsu-human-subjects-research/ (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Palan, Stefan, and Christian Schitter. 2018. Prolific.Ac—A Subject Pool for Online Experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 17: 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, Eyal, Laura Brandimarte, Sonam Samat, and Alessandro Acquisti. 2017. Beyond the Turk: Alternative Platforms for Crowdsourcing Behavioral Research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 70: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, James Allan Cheyne, Derek J. Koehler, and Jonathan A. Fugelsang. 2015a. Is the Cognitive Reflection Test a Measure of Both Reflection and Intuition? Behavior Research Methods 48: 341–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, Gordon, Jonathan A. Fugelsang, and Derek J. Koehler. 2015b. What Makes Us Think? A Three-Stage Dual-Process Model of Analytic Engagement. Cognitive Psychology 80: 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrodin, David D, and Richard Watson Todd. 2021. Choices in Asynchronously Collecting Qualitative Data: Moving from Written Responses to Spoken Responses for Open-Ended Queries. DRAL4 2021: 11. Available online: https://sola.pr.kmutt.ac.th/dral2021/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/3.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Petitmengin, Claire, Anne Remillieux, Béatrice Cahour, and Shirley Carter-Thomas. 2013. A Gap in Nisbett and Wilson’s Findings? A First-Person Access to Our Cognitive Processes. Consciousness and Cognition 22: 654–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonic Inc. 2020. Surveys You Can Answer with Your Voice. Available online: phonic.ai (accessed on 21 February 2020).

- Purcell, Zoë A., Colin A. Wastell, and Naomi Sweller. 2021. Domain-Specific Experience and Dual-Process Thinking. Thinking & Reasoning 27: 239–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooler, Jonathan W., Stellan Ohlsson, and Kevin Brooks. 1993. Thoughts beyond Words: When Language Overshadows Insight. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 122: 166–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, Nicholas, and Chris D. Frith. 2016. Dual-Process Theories and Consciousness: The Case for “Type Zero” Cognition. Neuroscience of Consciousness 2016: niw005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, Joseph P., Leif D. Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn. 2013. Life after P-Hacking. Paper presented at Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, New Orleans, LA, USA, January 17–19; p. 38. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2205186 (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Sirota, Miroslav, Lenka Kostovičová, Marie Juanchich, Chris Dewberry, and Amanda Claire Marshall. 2021. Measuring Cognitive Reflection without Maths: Developing and Validating the Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 34: 322–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobkow, Agata, Angelika Olszewska, and Miroslav Sirota. 2023. The Factor Structure of Cognitive Reflection, Numeracy, and Fluid Intelligence: The Evidence from the Polish Adaptation of the Verbal CRT. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 36: e2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnaro, Michael N., Gordon Pennycook, and David G. Rand. 2018. Performance on the Cognitive Reflection Test Is Stable across Time. Judgment and Decision Making 13: 260–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, Keith E. 2018. Miserliness in Human Cognition: The Interaction of Detection, Override and Mindware. Thinking & Reasoning 24: 423–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, Stefan, and Ulf-Dietrich Reips. 2016. A Limitation of the Cognitive Reflection Test: Familiarity. PeerJ 4: e2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2007. Measuring Deliberation’s Content: A Coding Scheme. Journal of Public Deliberation 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupple, Edward J. N., Melanie Pitchford, Linden J. Ball, Thomas E. Hunt, and Richard Steel. 2017. Slower Is Not Always Better: Response-Time Evidence Clarifies the Limited Role of Miserly Information Processing in the Cognitive Reflection Test. PLoS ONE 12: e0186404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaszi, Barnabas, Aba Szollosi, Bence Palfi, and Balazs Aczel. 2017. The Cognitive Reflection Test Revisited: Exploring the Ways Individuals Solve the Test. Thinking & Reasoning 23: 207–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Valerie A., and Stephen C. Johnson. 2014. Conflict, Metacognition, and Analytic Thinking. Thinking & Reasoning 20: 215–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Valerie A., Jamie A. Prowse Turner, and Gordon Pennycook. 2011. Intuition, Reason, and Metacognition. Cognitive Psychology 63: 107–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, Valerie A., Jonathan Evans, and Jamie I. D. Campbell. 2013. Matching Bias on the Selection Task: It’s Fast and Feels Good. Thinking & Reasoning 19: 431–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, Maggie E., Richard F. West, and Keith E. Stanovich. 2014. Assessing Miserly Information Processing: An Expansion of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Thinking & Reasoning 20: 147–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Timothy, and Richard E. Nisbett. 1978. The Accuracy of Verbal Reports About the Effects of Stimuli on Evaluations and Behavior. Social Psychology 41: 118–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Example Verbalization | Answer | Standard | Two-Factor | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct-and-reflective | “1st obviously. No actually … 2nd.” | Correct | Reflective | Reflective | 80.2% |

| Correct-but-unreflective | “2nd” | Correct | Reflective | Unreflective | 19.8% |

| Lured-and-unreflective | “1st” | Lured | Unreflective | Unreflective | 71.5% |

| Lured-yet-reflective | “I want to say 1st but, umm, yeah, 1st.” | Lured | Unreflective | Reflective | 28.5% |

| Categorization | Example Verbalization | Answer | Standard | Two-Factor | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct-and-reflective | “1st. No … 2nd. Whoopsie” | Correct | Reflective | Reflective | 68.5% |

| Correct-but-unreflective | “2nd” | Correct | Reflective | Unreflective | 31.5% |

| Lured-and-unreflective | “1st” | Lured | Unreflective | Unreflective | 75.8% |

| Lured-yet-reflective | “1st … or is that a trick? … I’d say 1st.” | Lured | Unreflective | Reflective | 24.2% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Byrd, N.; Joseph, B.; Gongora, G.; Sirota, M. Tell Us What You Really Think: A Think Aloud Protocol Analysis of the Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test. J. Intell. 2023, 11, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11040076

Byrd N, Joseph B, Gongora G, Sirota M. Tell Us What You Really Think: A Think Aloud Protocol Analysis of the Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test. Journal of Intelligence. 2023; 11(4):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11040076

Chicago/Turabian StyleByrd, Nick, Brianna Joseph, Gabriela Gongora, and Miroslav Sirota. 2023. "Tell Us What You Really Think: A Think Aloud Protocol Analysis of the Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test" Journal of Intelligence 11, no. 4: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11040076

APA StyleByrd, N., Joseph, B., Gongora, G., & Sirota, M. (2023). Tell Us What You Really Think: A Think Aloud Protocol Analysis of the Verbal Cognitive Reflection Test. Journal of Intelligence, 11(4), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence11040076