Numerical Error Analysis of the Poisson Equation Under RHS Inaccuracies in Particle-in-Cell Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model and Numerical Formulation

2.1. Poisson Equation and Discretization Schemes

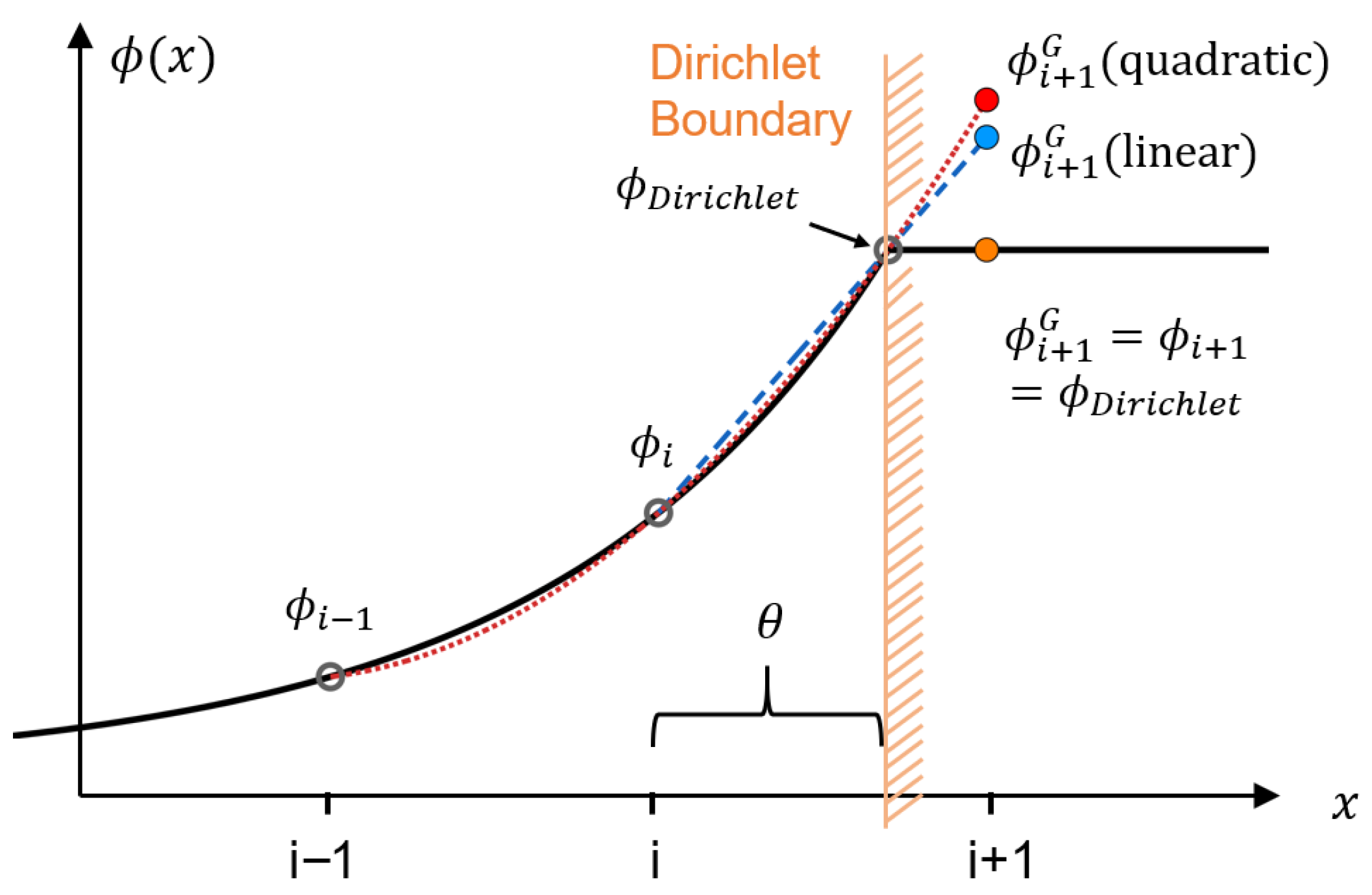

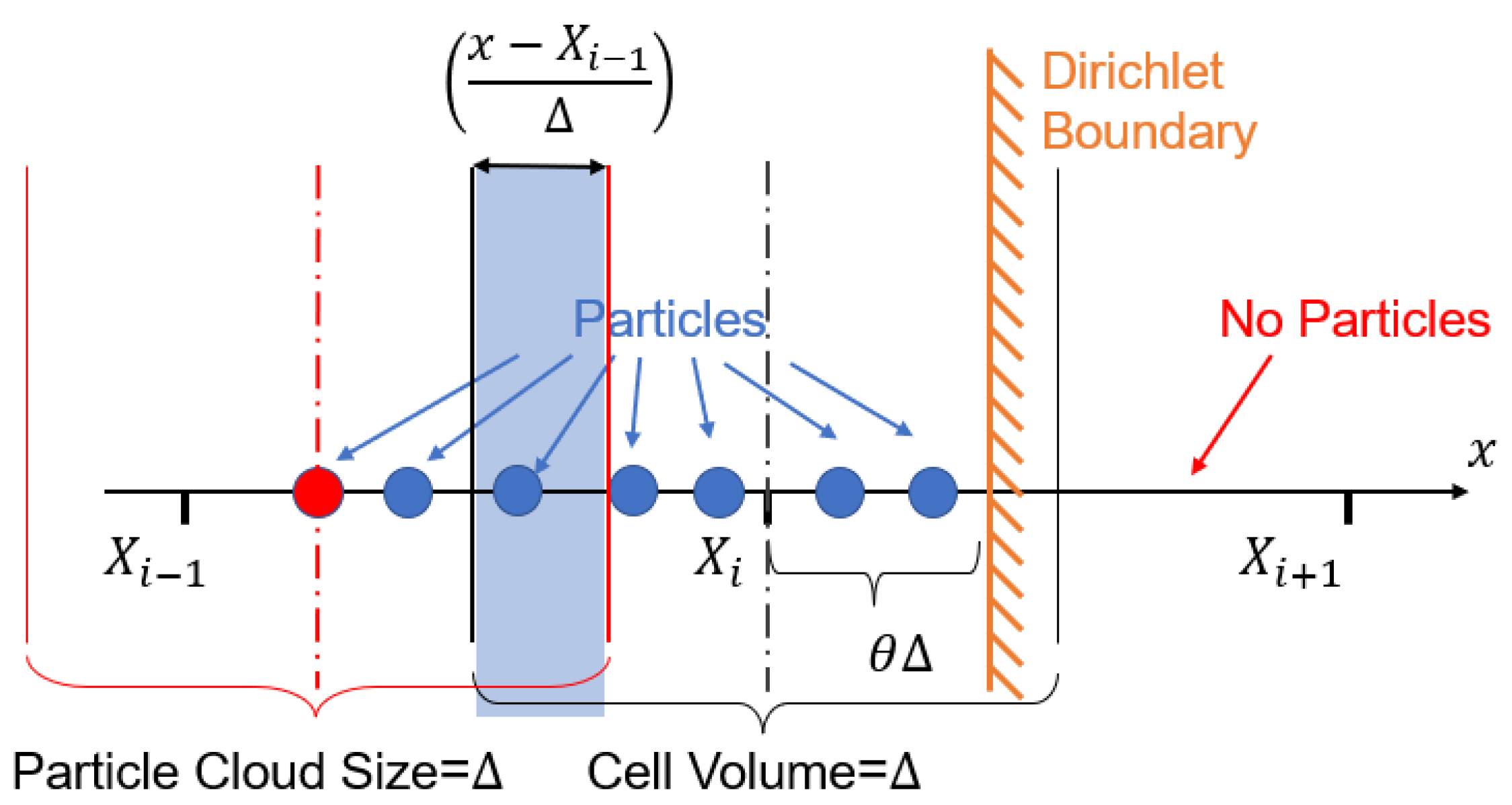

2.2. Numerical Treatments for RHS Values

3. Error Analysis

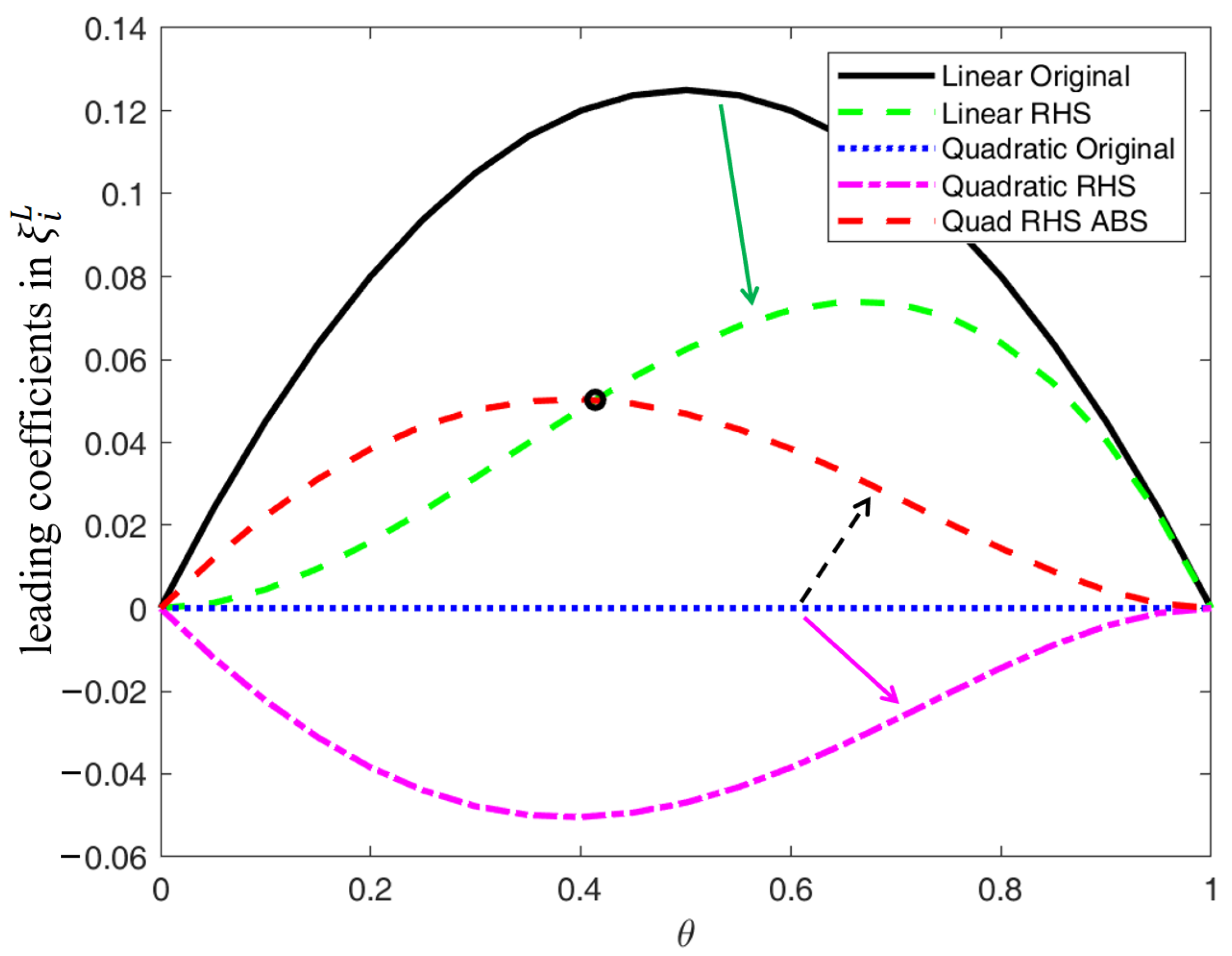

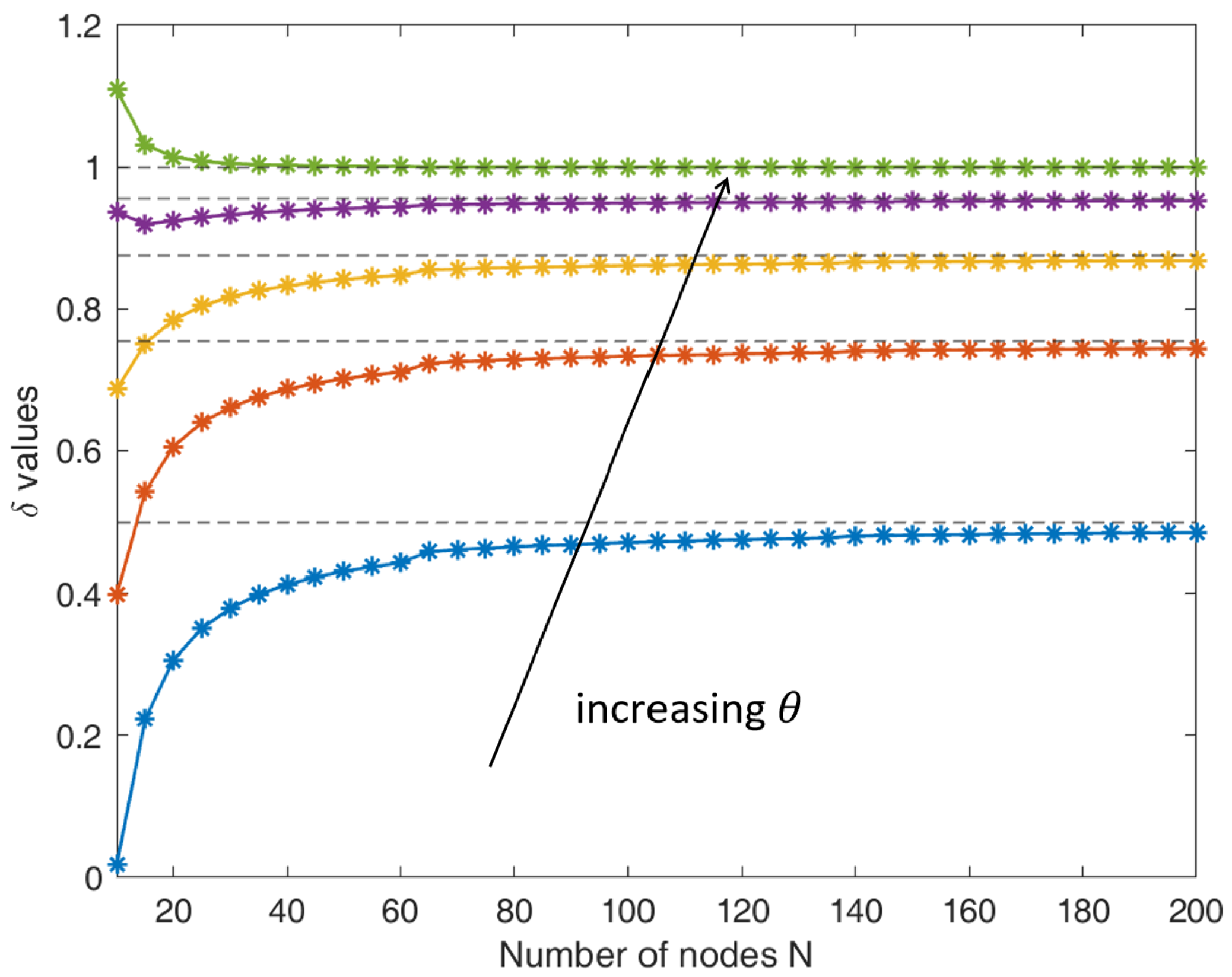

3.1. One-Dimensional Error Analysis

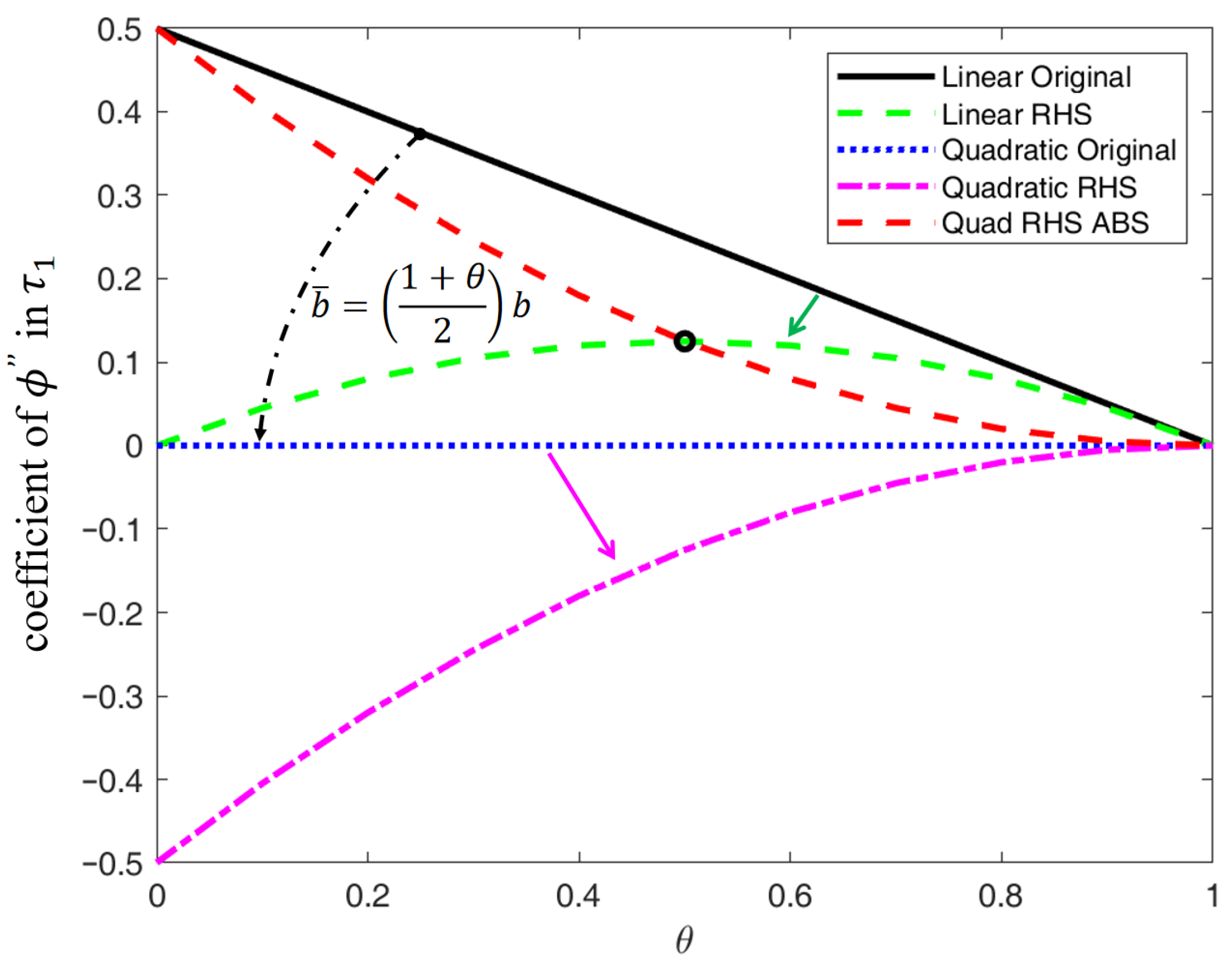

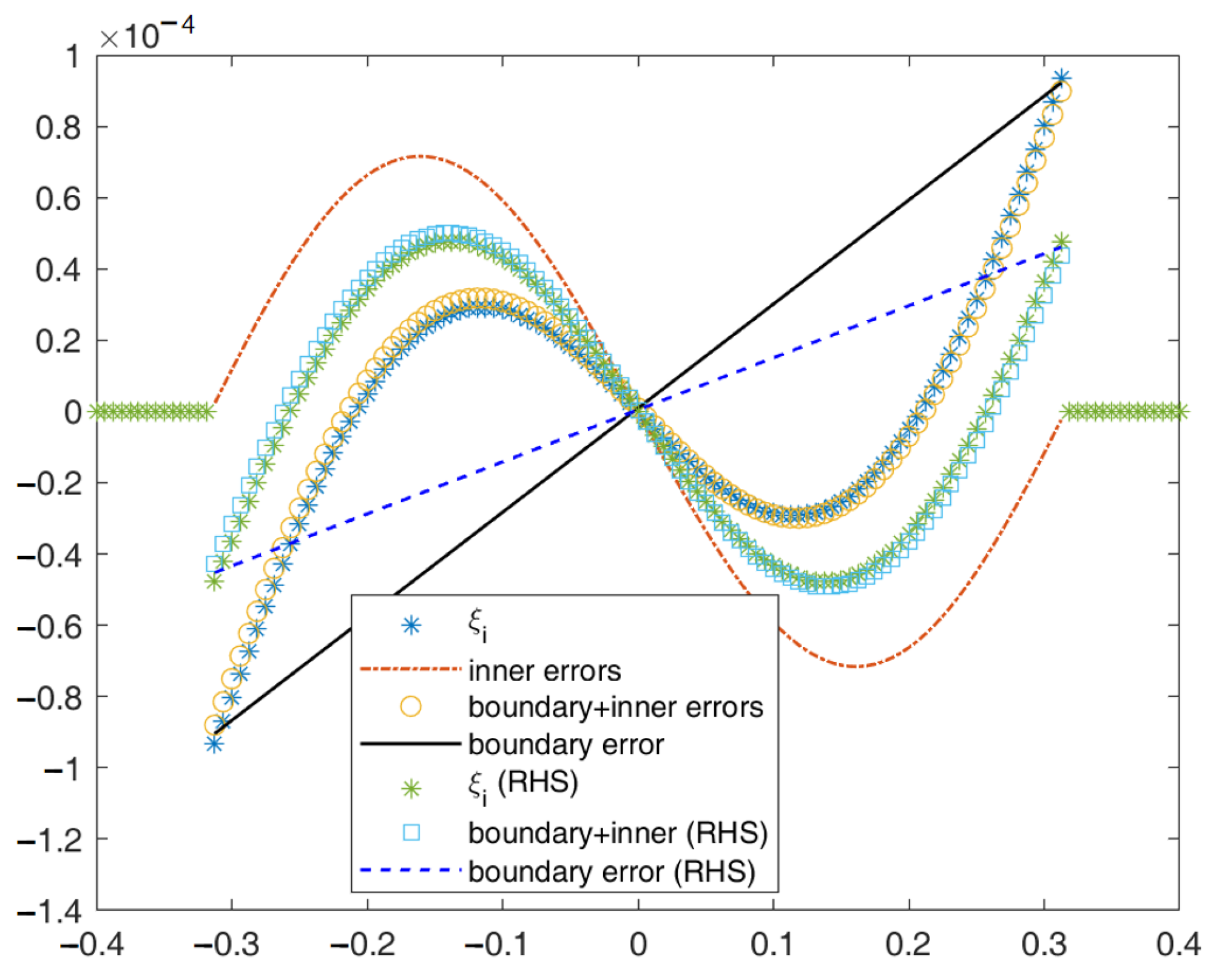

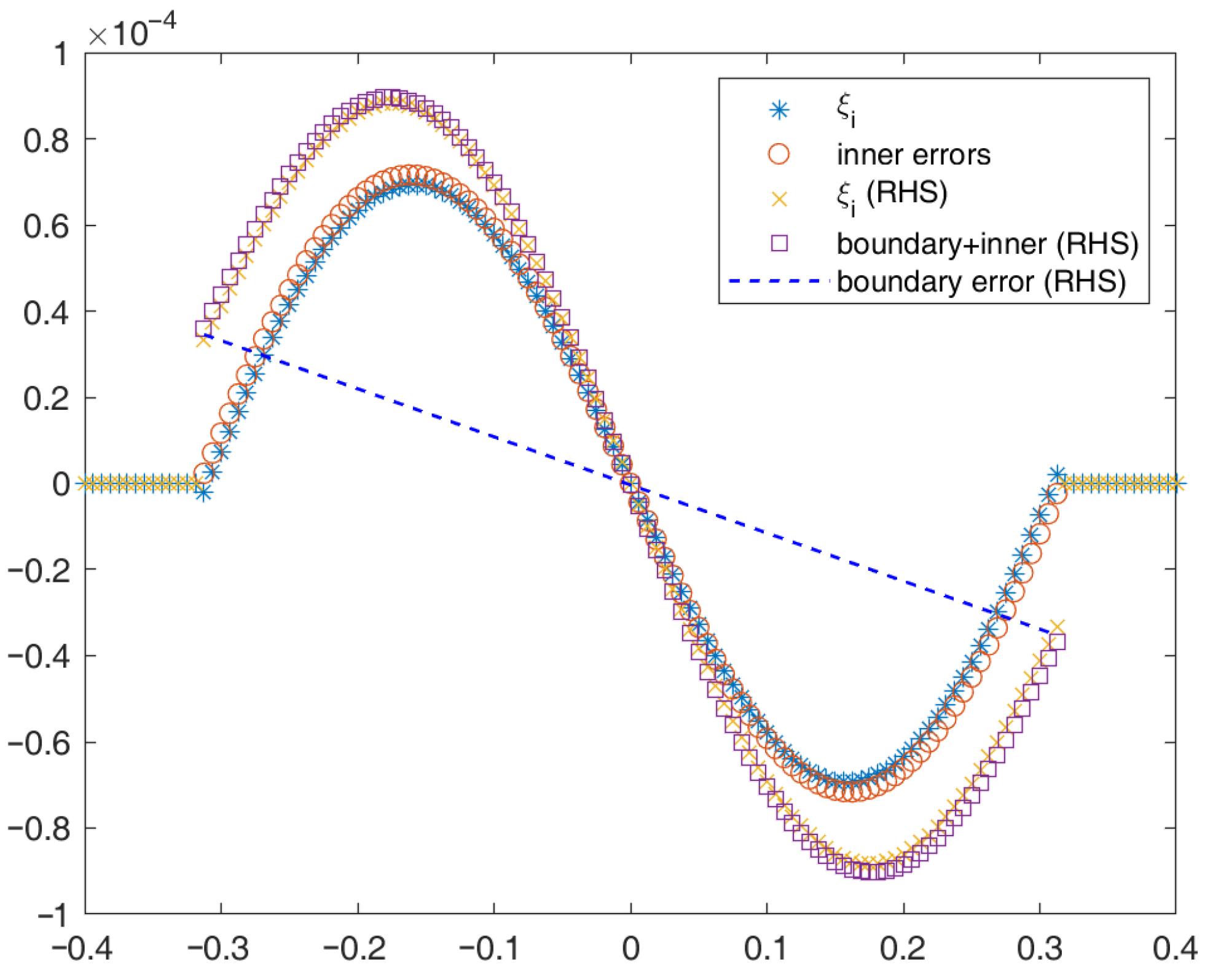

3.1.1. The Linear Scheme Case

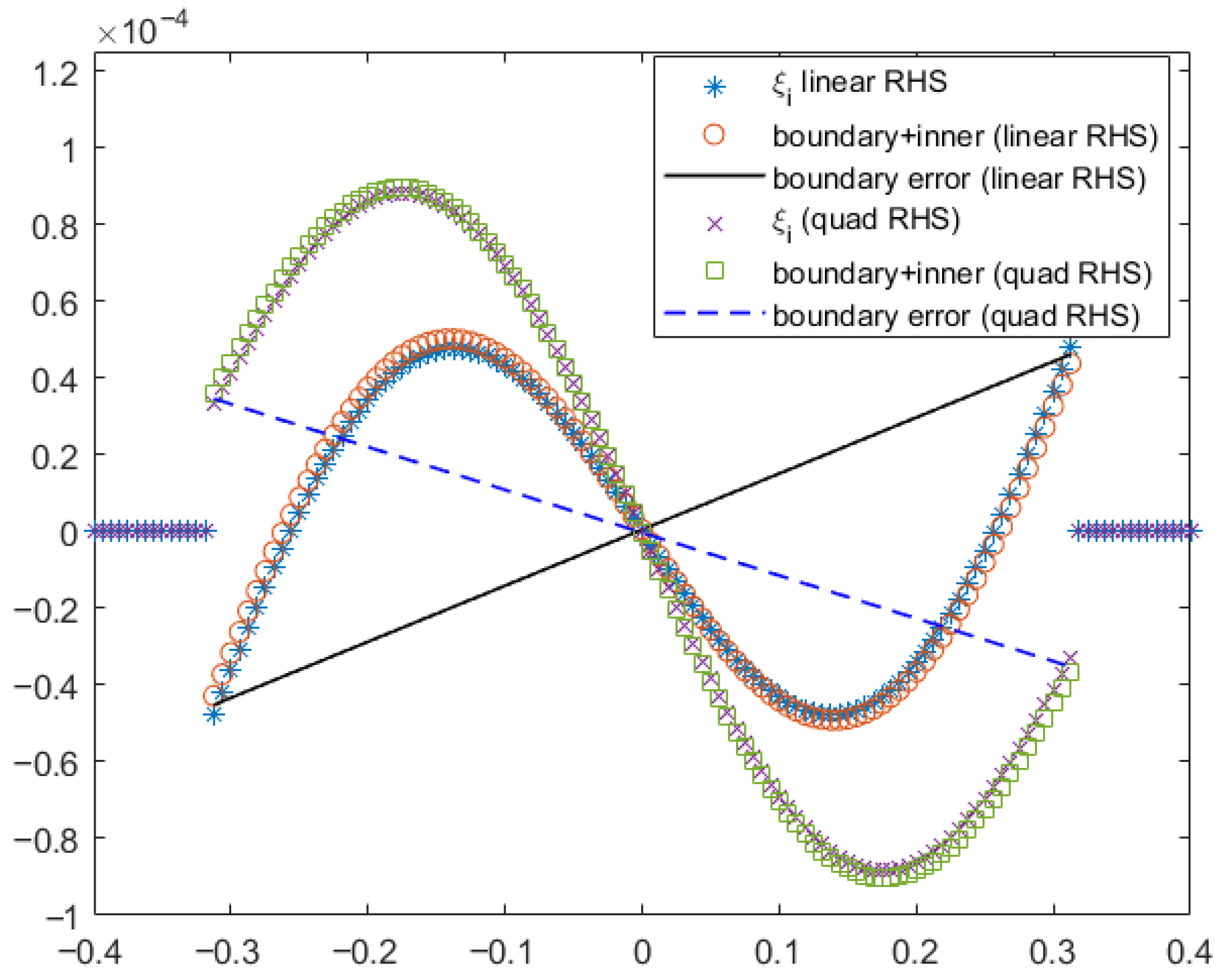

3.1.2. The Quadratic Scheme Case

3.1.3. Overview of 1D Error Analysis

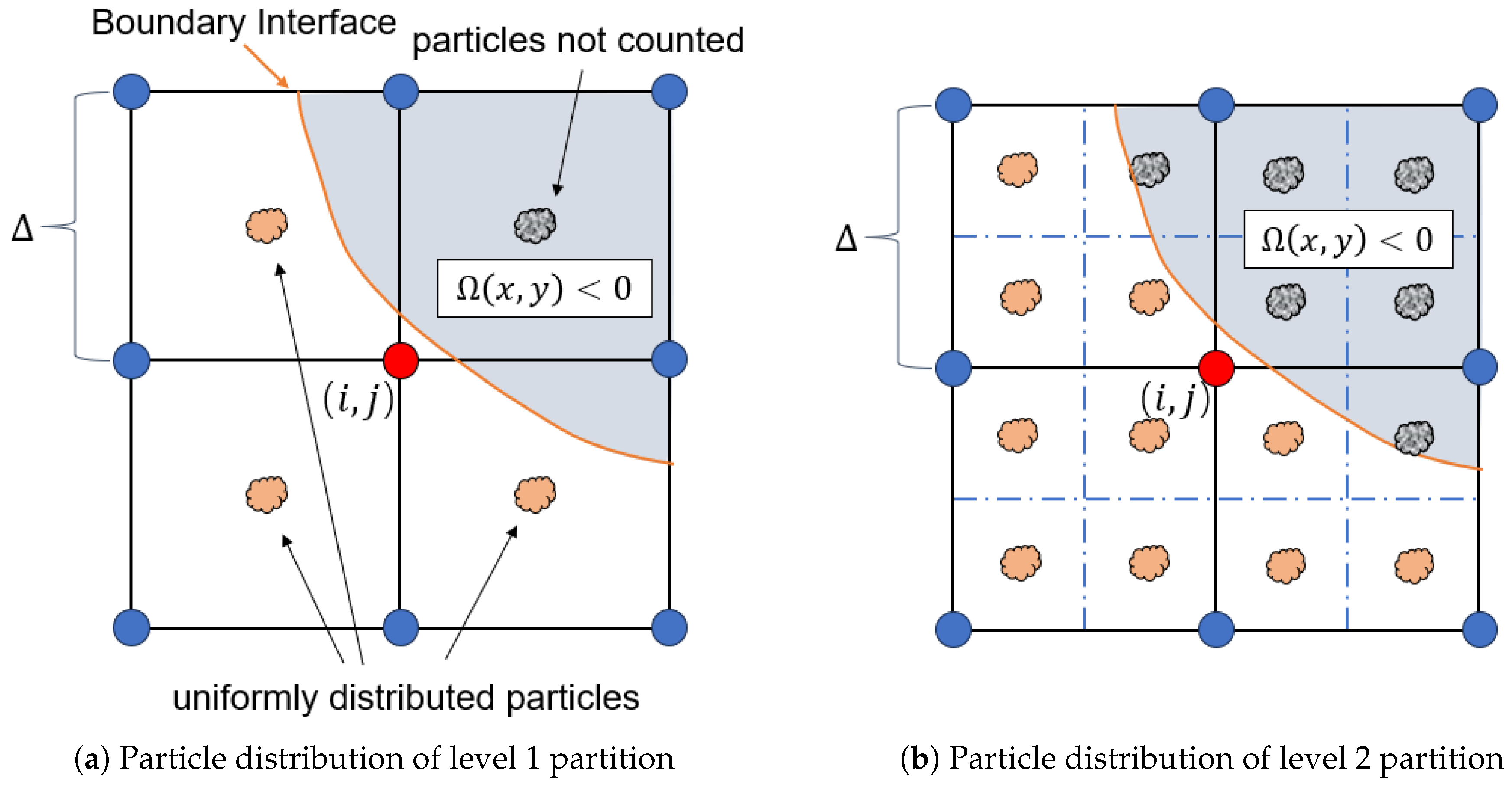

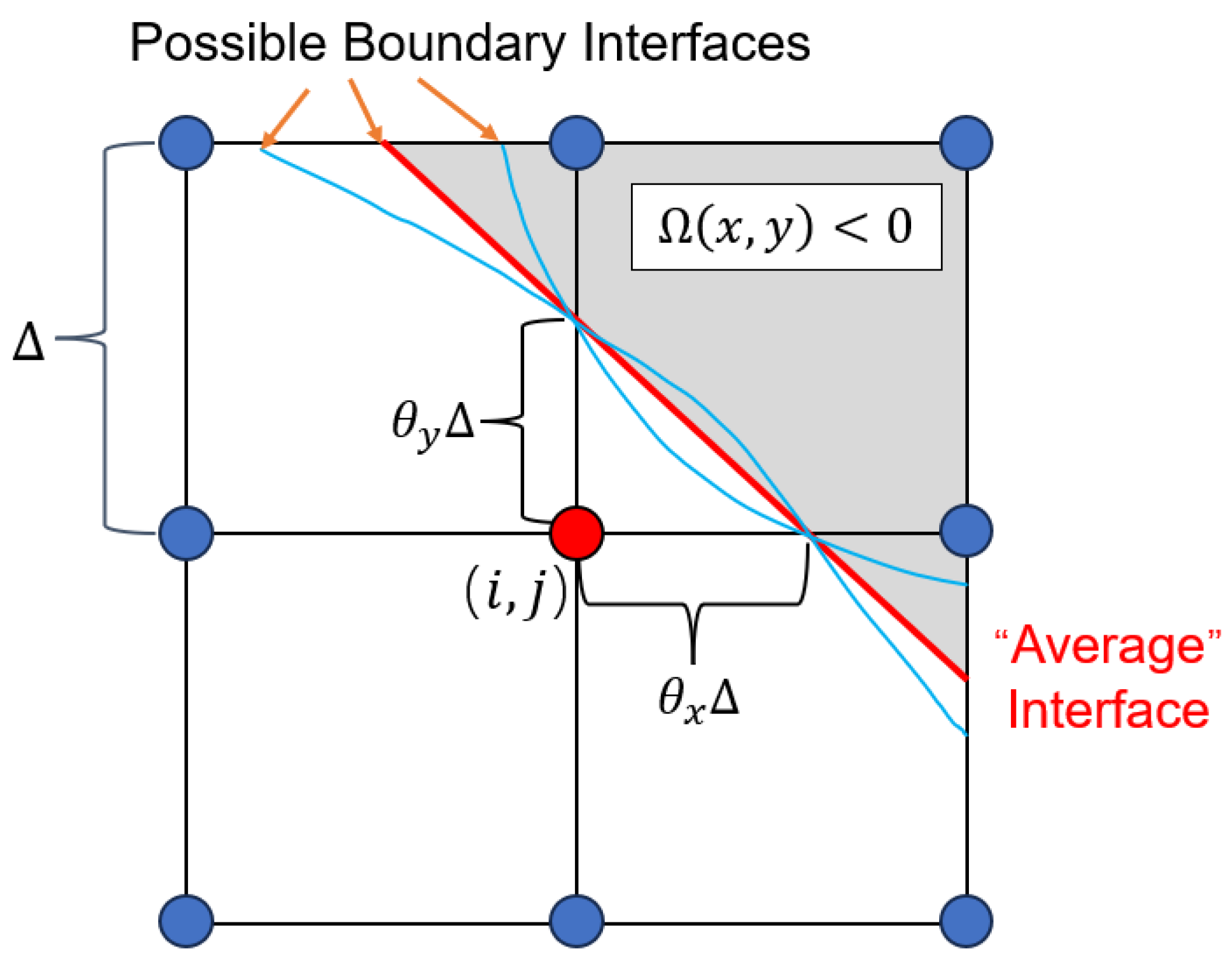

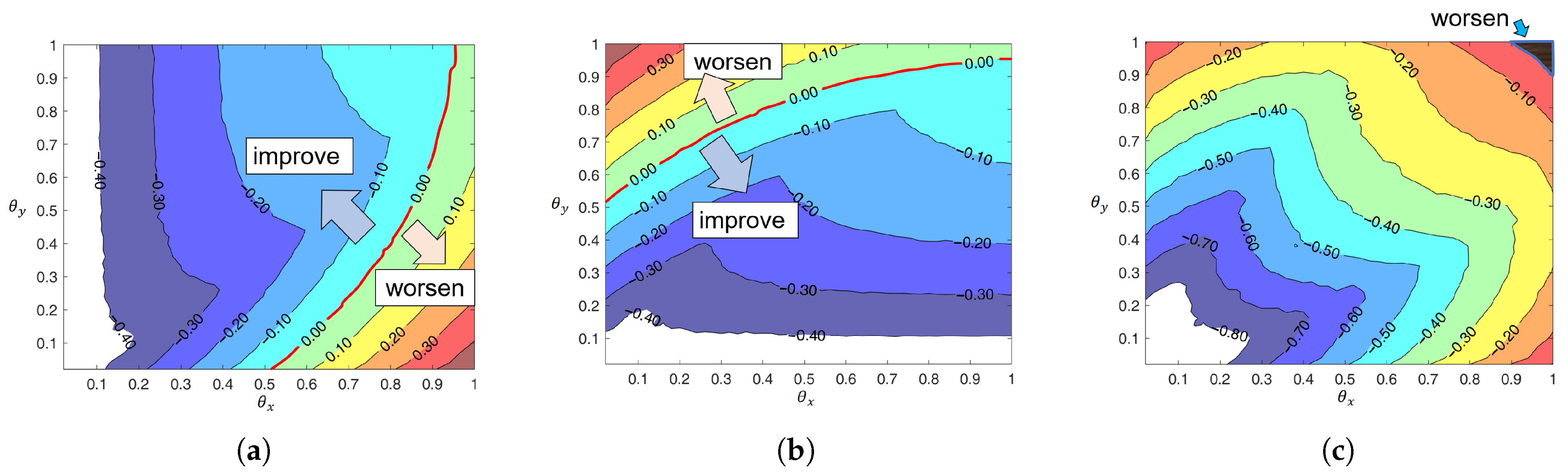

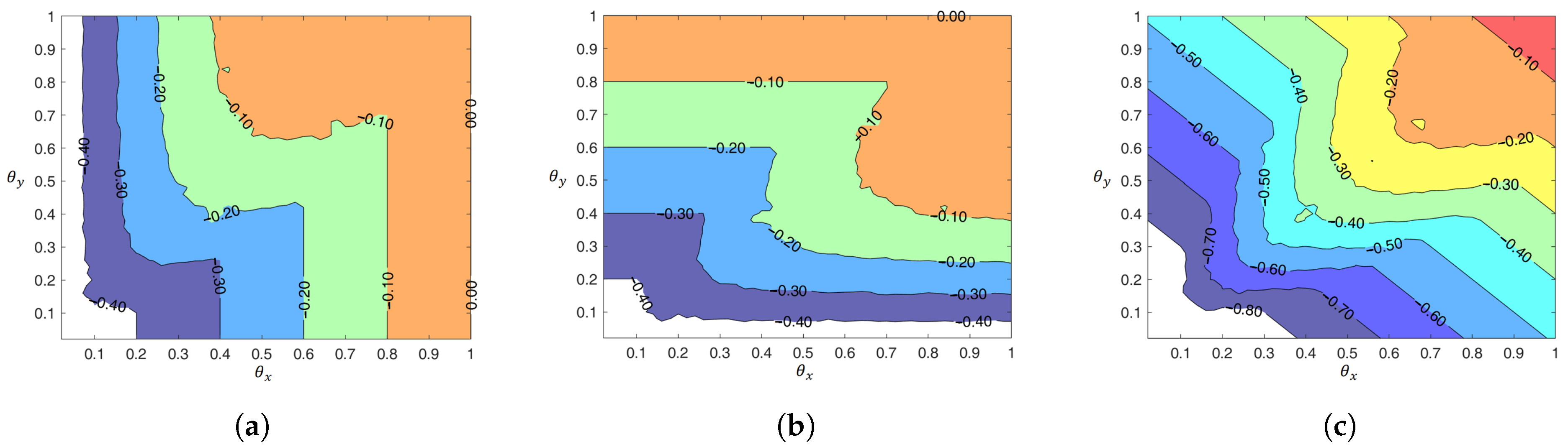

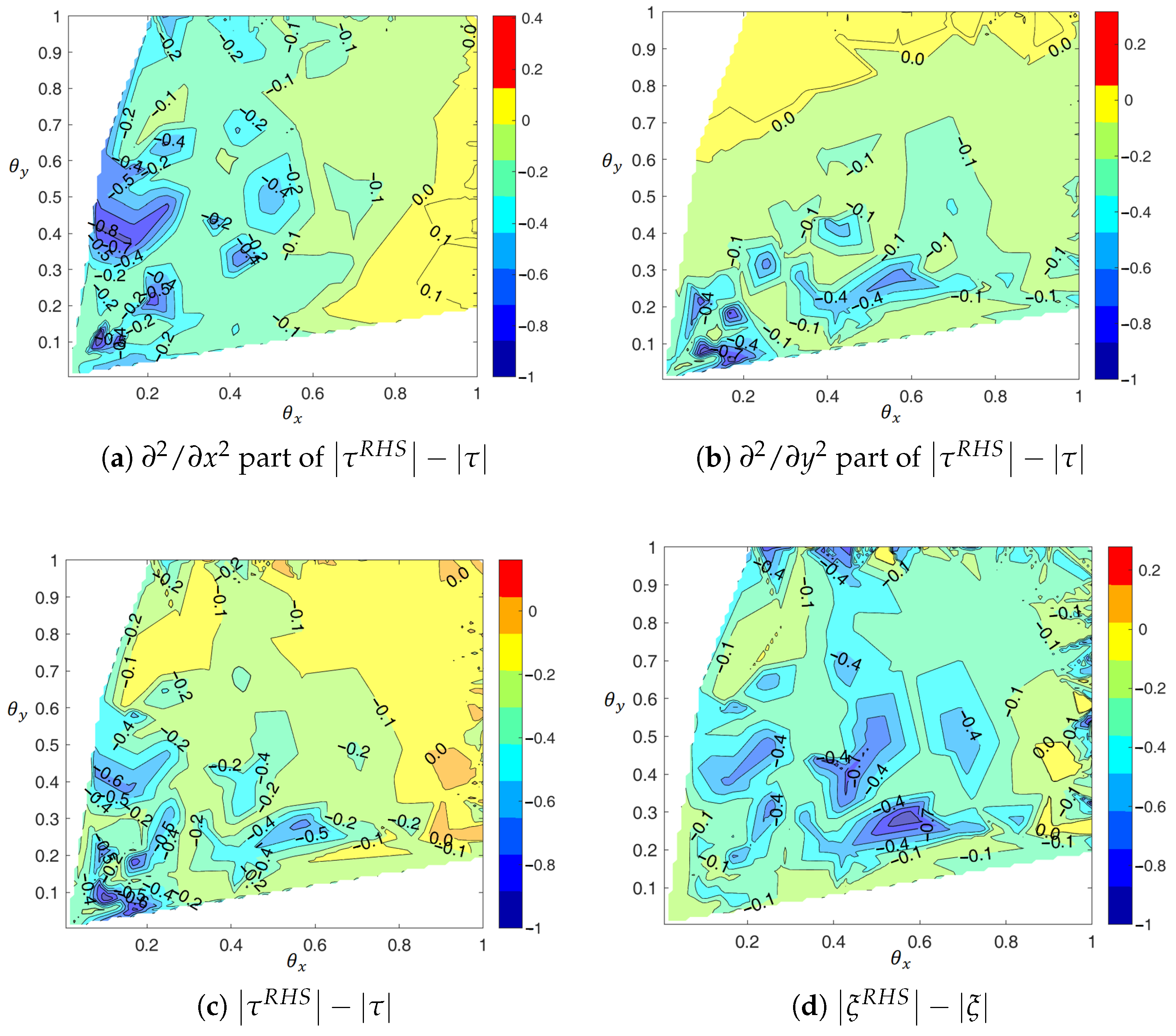

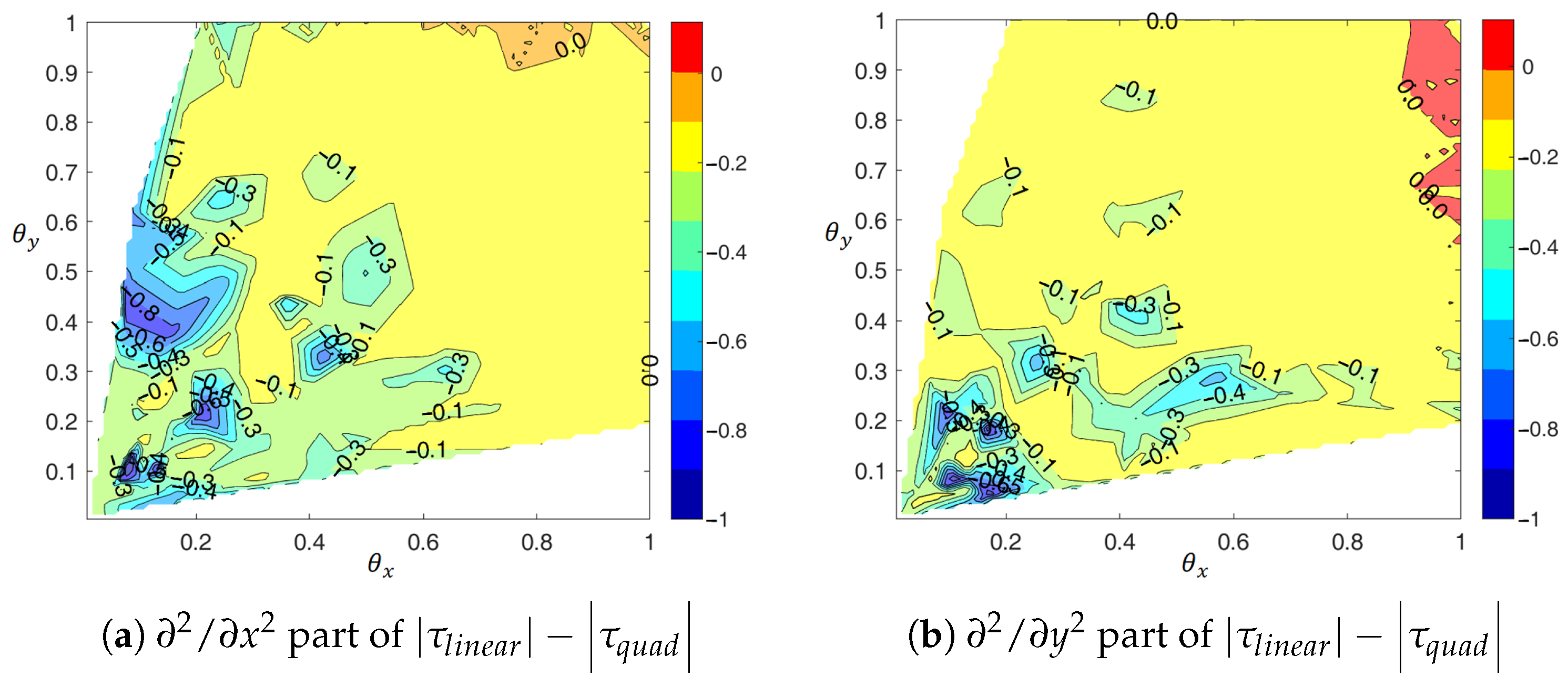

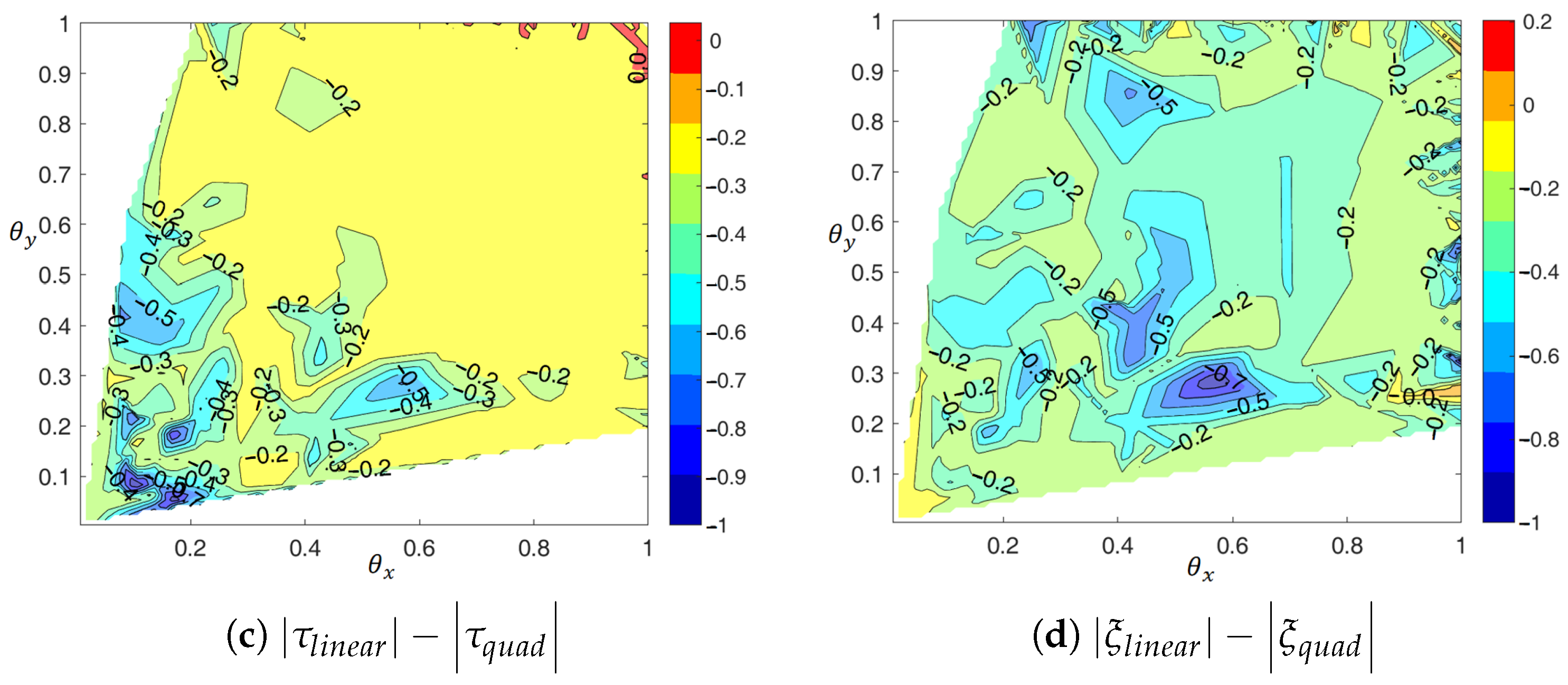

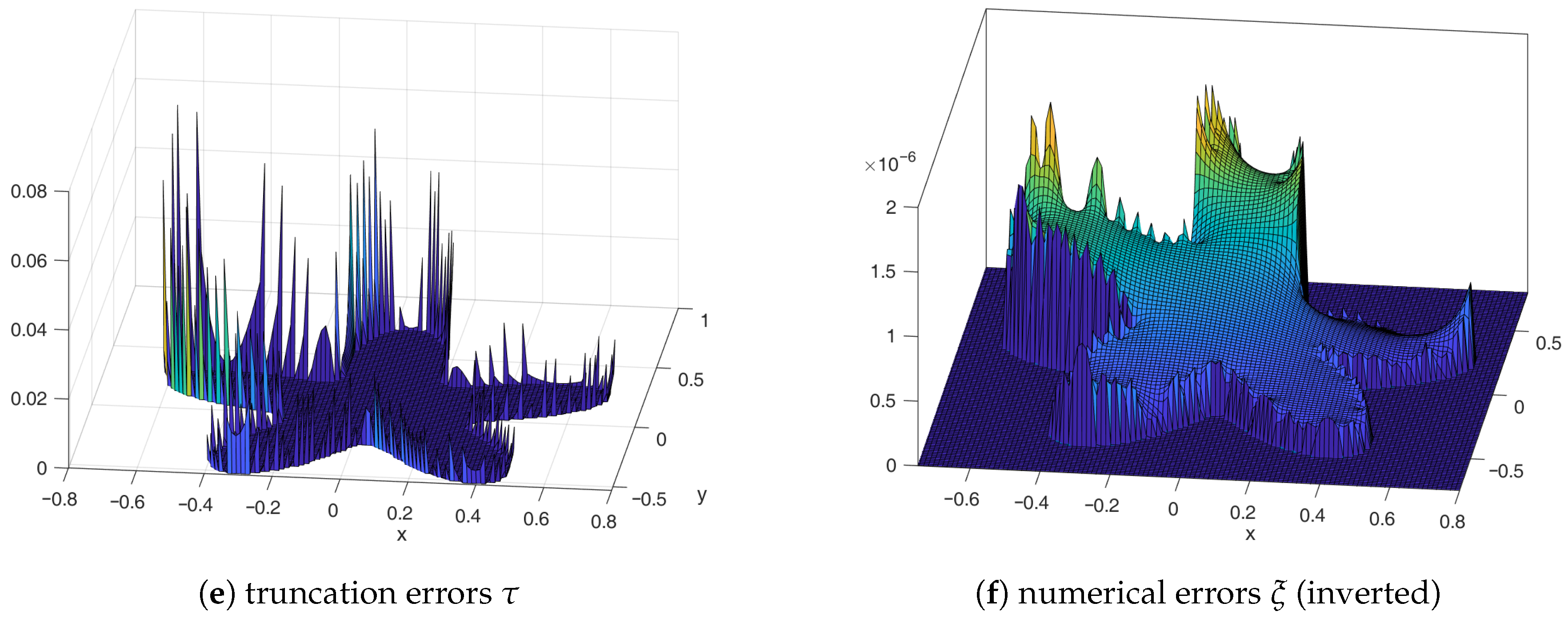

3.2. Two-Dimensional Error Analysis

4. Test Cases and Results

- One-dimensional example. Poisson equation is to be solved in a 1D domain with the exact solution given by , which determines the RHS values by . Dirichlet boundaries are defined such that denotes the outside region. The domain is chosen so that the computational interval has unit length and is centered at the origin, which simplifies grid refinement and yields clearer visualization of the solution and error profiles.

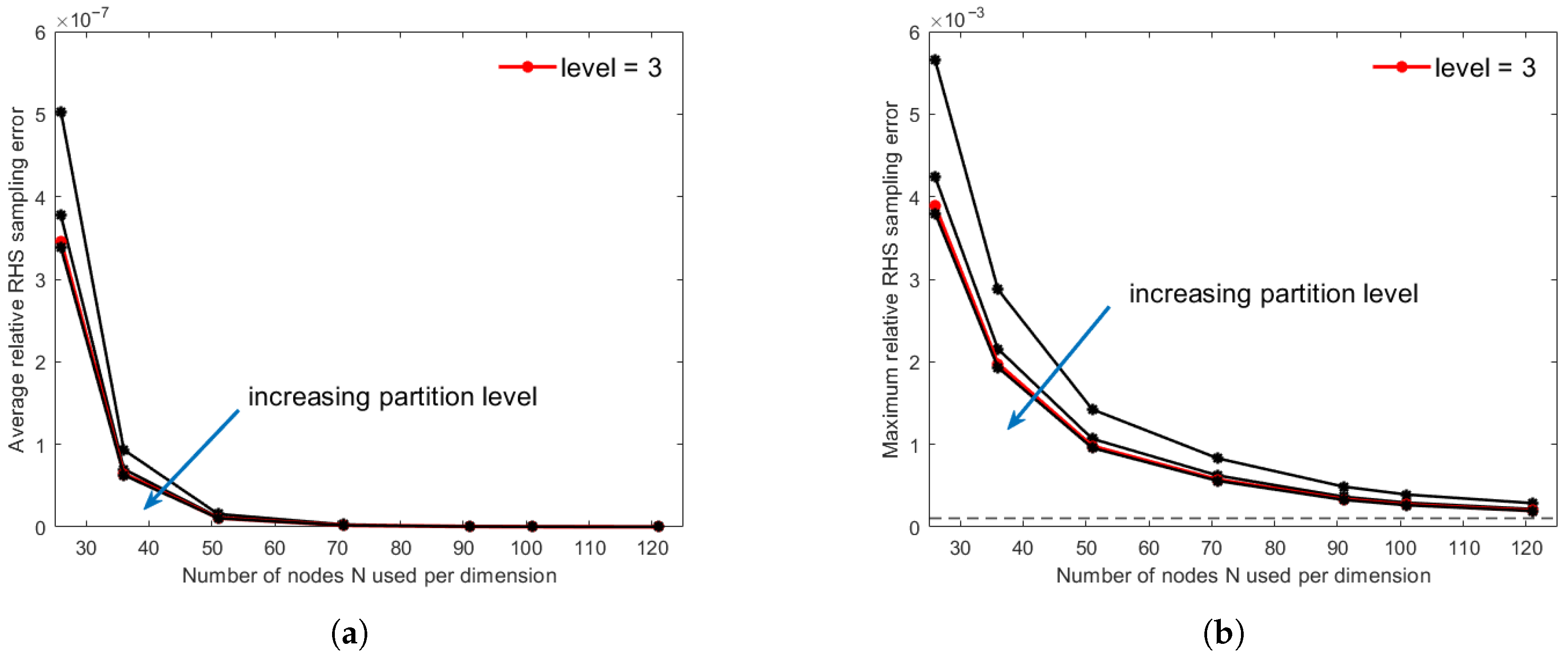

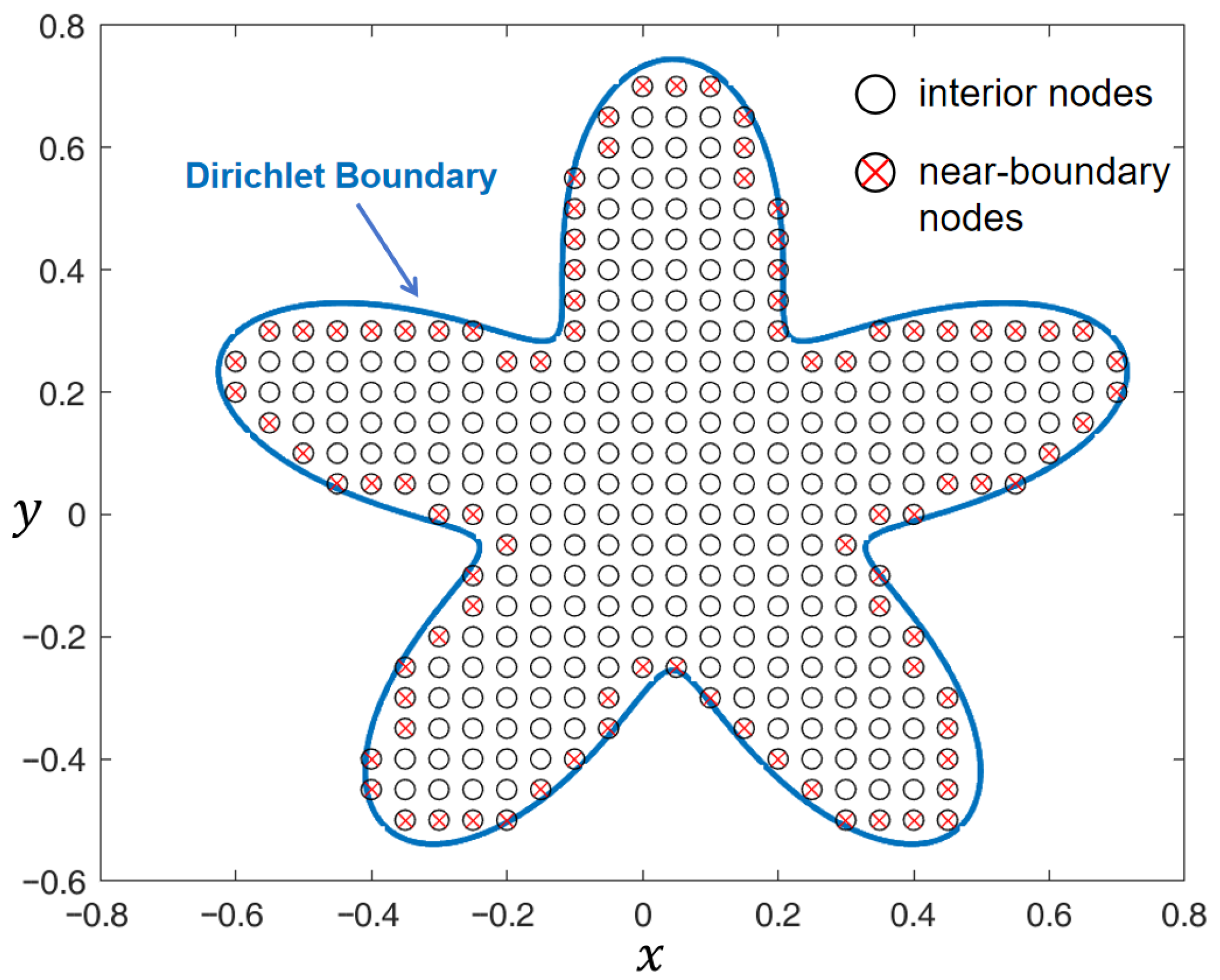

- Two-dimensional example. The 2D Poisson equation is defined in a square area , with an exact solution , which has the corresponding RHS values of . A closed Dirichlet boundary interface is defined by a pair of parameterized equations and , where , and . This Dirichlet interface is shaped like a starfish, whose inside contains all the inner grid nodes. In order to decide whether a grid node is inside the boundary and to calculate the and if it’s a near-boundary node, it is recommended that the calculations are done in a shifted polar coordinate system originated at , then any point that is within the radius of is inside the boundary.

- Three-dimensional example. The 3D Poisson equation is solved within a cubic domain , where a spherical boundary decides the inner nodes by , where . The exact solution is given by , from which the RHS values are computed as .

4.1. One-Dimensional Numerical Test Results

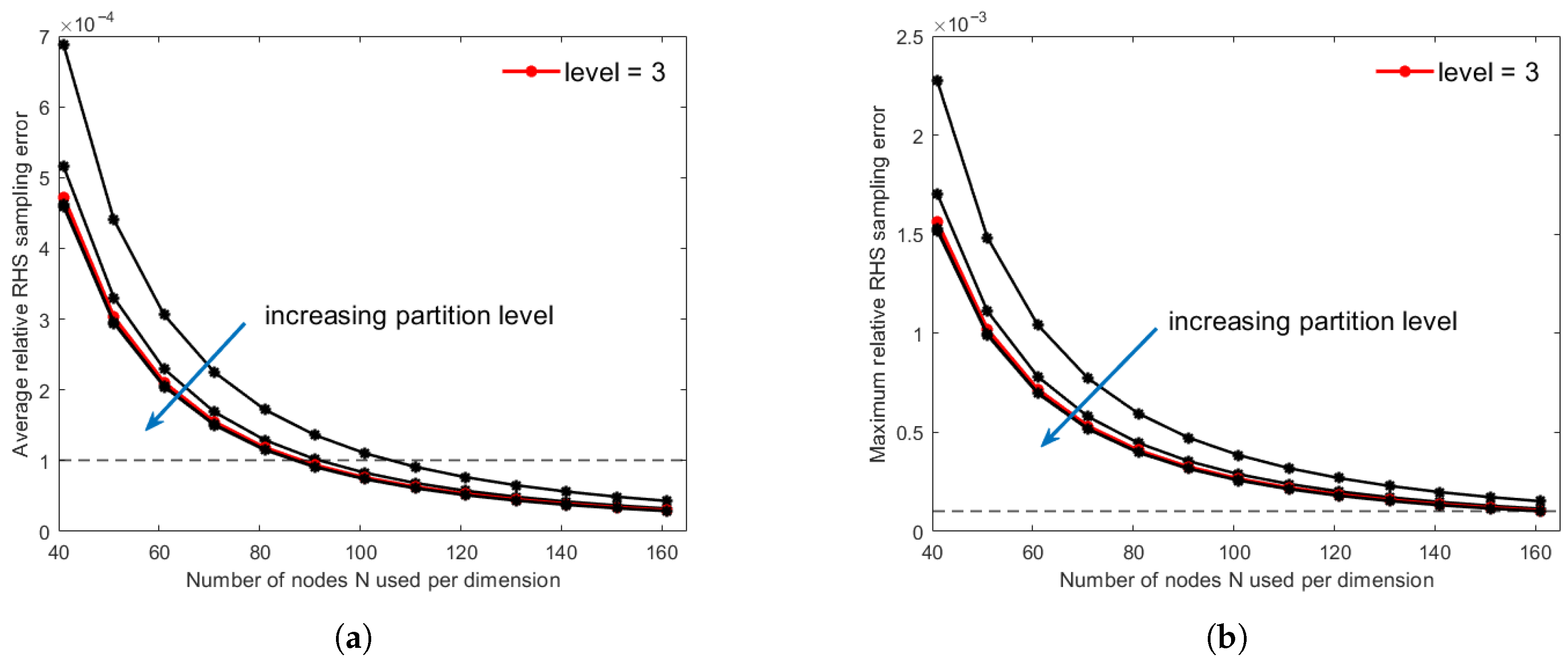

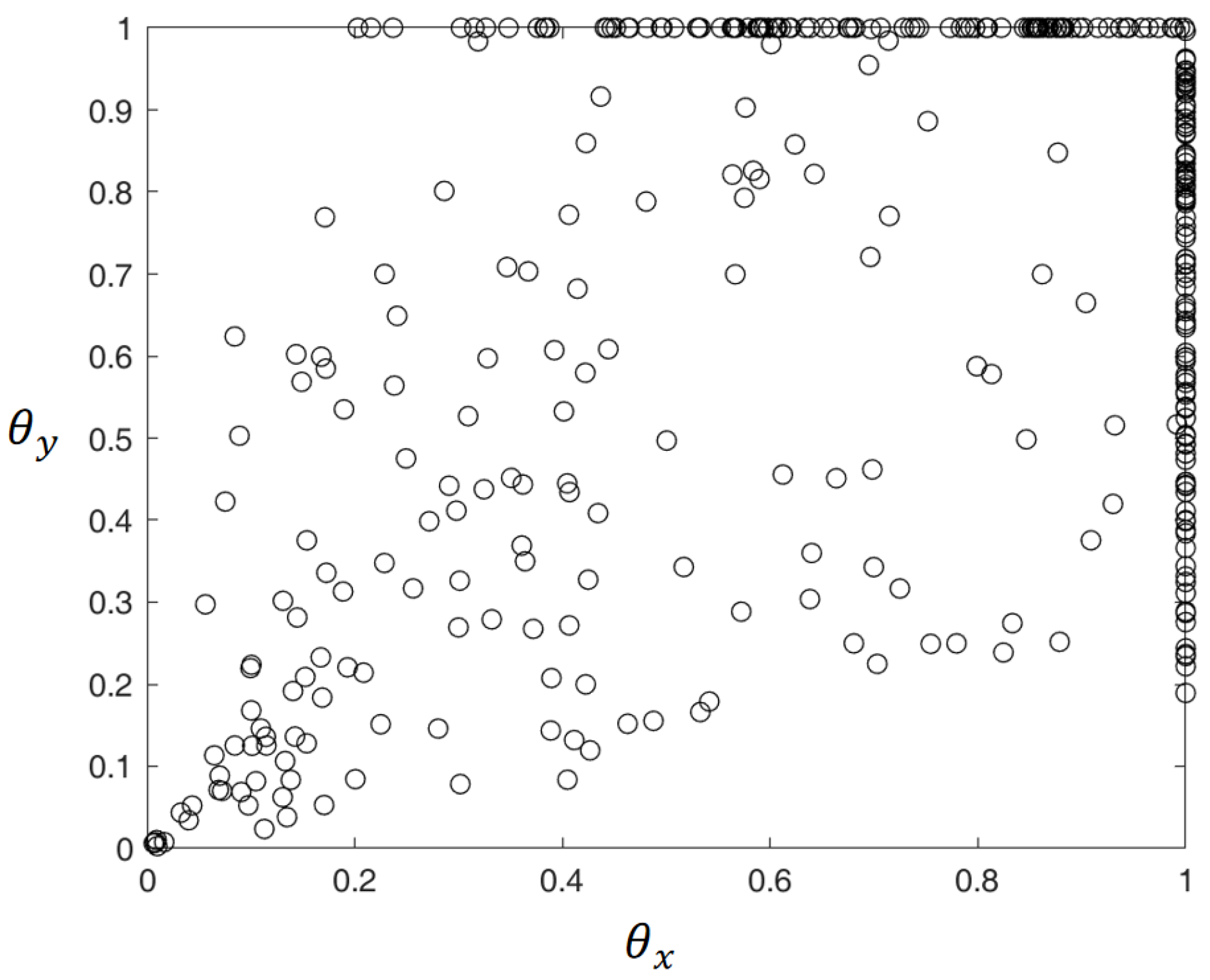

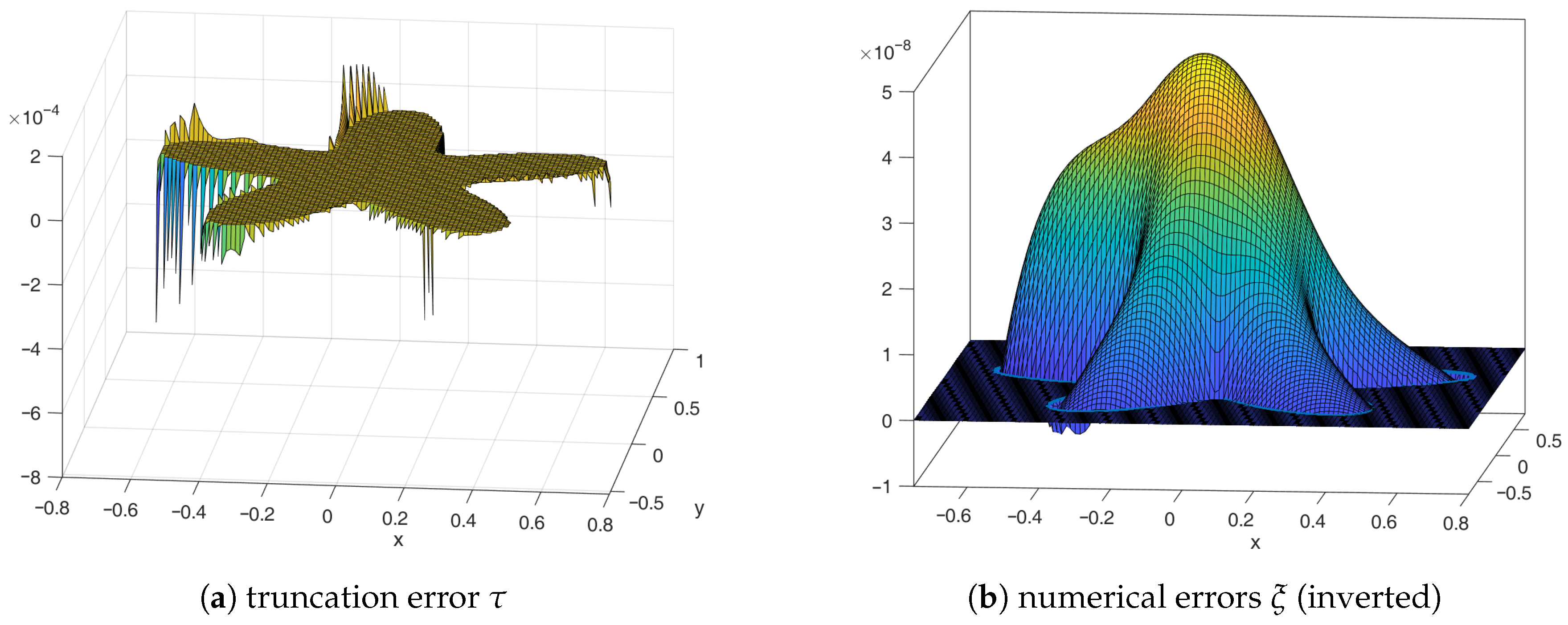

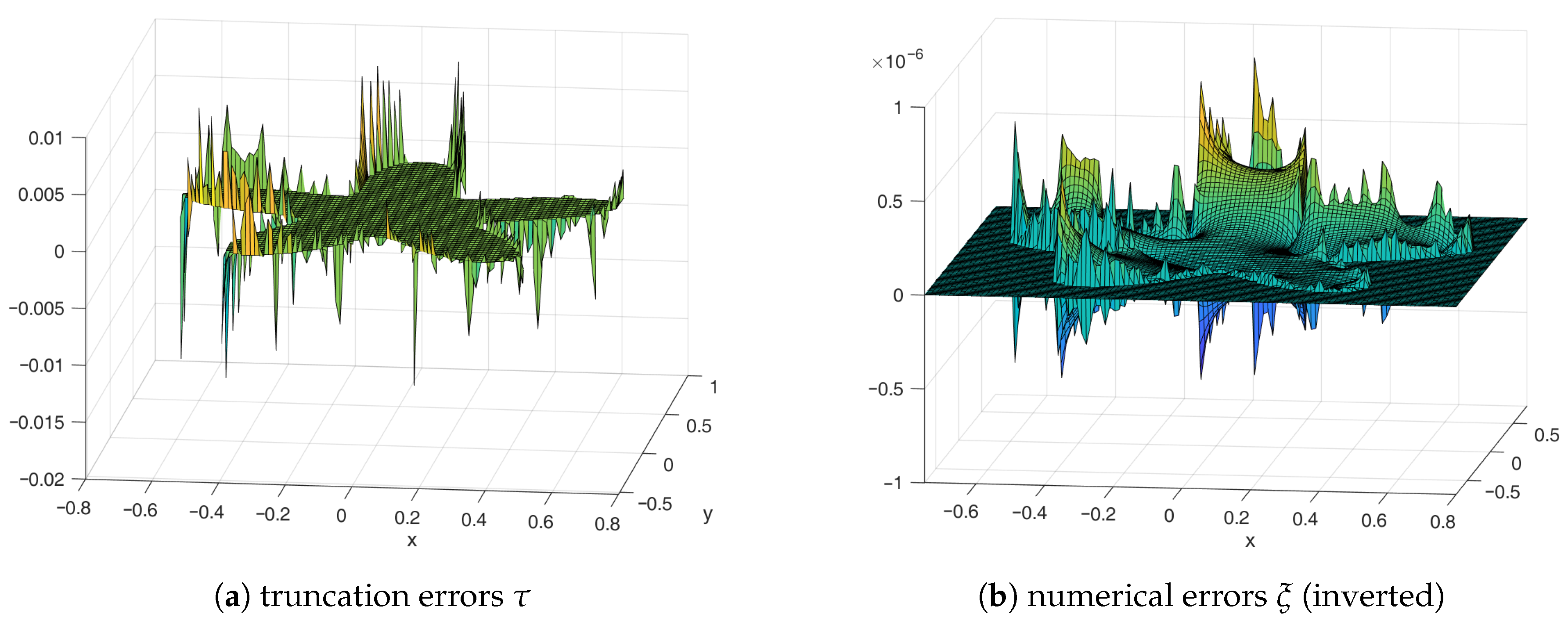

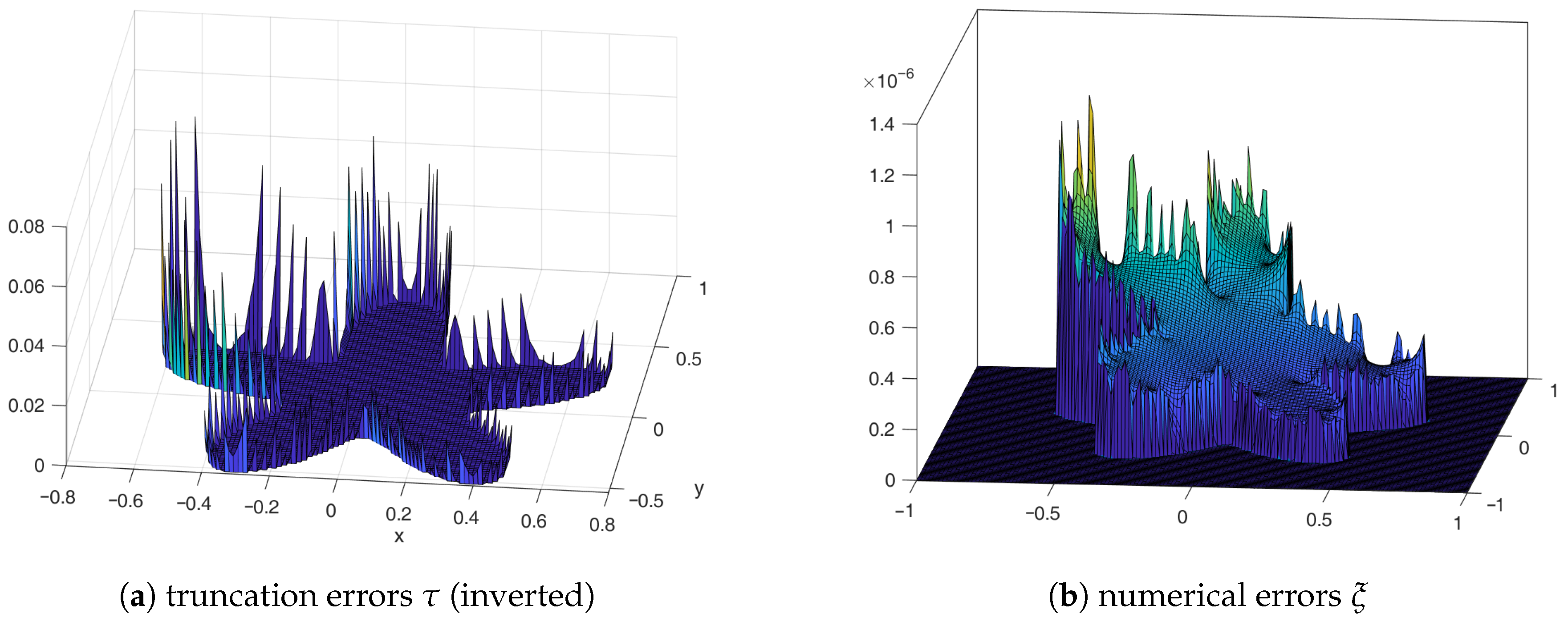

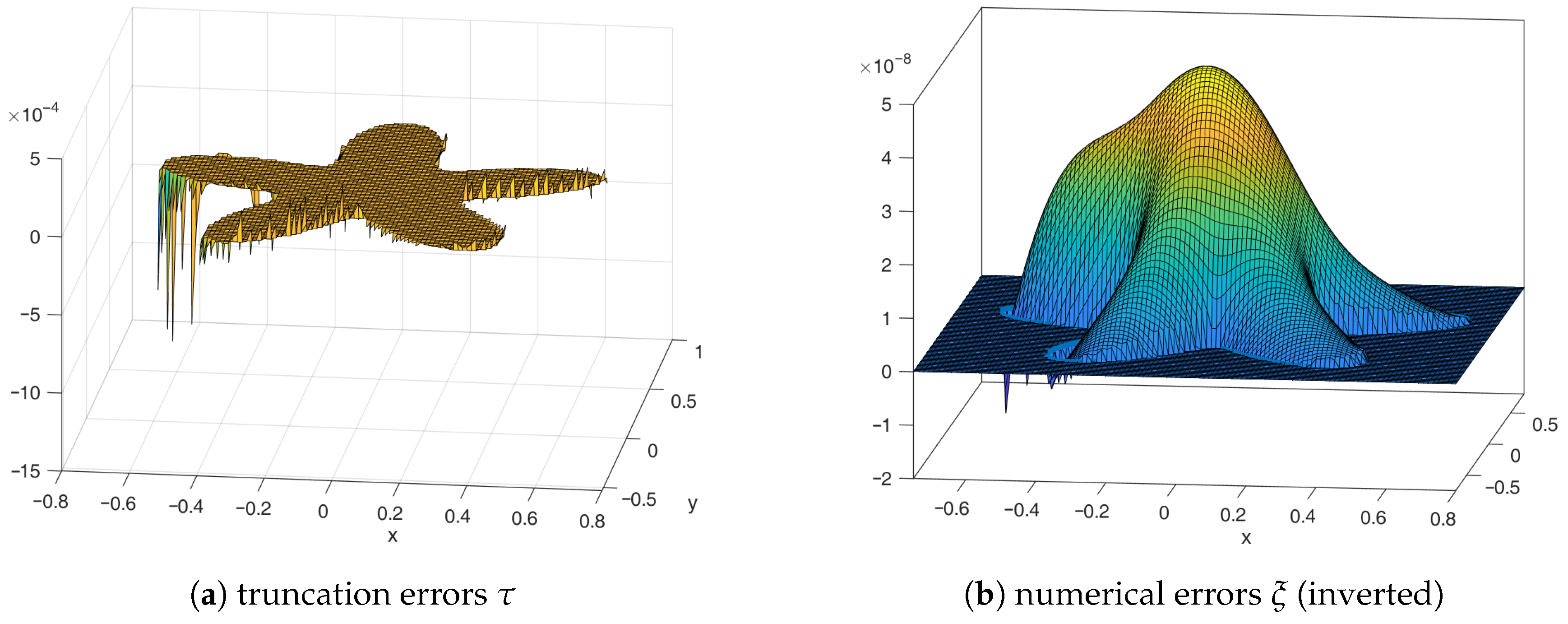

4.2. Two-Dimensional/Three-Dimensional Numerical Tests and Discussions

4.2.1. Boundary and for the 2D Case

4.2.2. Global Accuracy Assessment and RHS Error Compensation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIC | Particle-in-Cell |

| RHS | Right-Hand Side |

| LHS | Left-Hand Side |

| 1D | One-Dimensional |

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| PCG | Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient |

| PIV | Particle Image Velocimetry |

| CFM | Correction Function Method |

| SPD | Symmetric Positive Definite |

References

- Birdsall, C.K.; Langdon, A.B. Plasma Physics via Computer Simulation; CRC press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Messmer, P.; Bruhwiler, D.L. A parallel electrostatic solver for the VORPAL code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2004, 164, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J. Efficient three-dimensional Poisson solvers in open rectangular conducting pipe. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016, 203, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaziev, R.; Curreli, D. hPIC: A scalable electrostatic particle-in-cell for plasma–material interactions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2018, 229, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cai, S.; Cai, C.; Cooke, D.L. A parallel particle-in-cell code for spacecraft charging problems. J. Plasma Phys. 2020, 86, 905860308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cai, G.; He, B.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, H.; Wang, W. Plume neutralization of an ionic liquid electrospray thruster: Better insights from particle-in-cell modelling. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2021, 30, 125009. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, I.H. Ion collection by a sphere in a flowing plasma: I. Quasineutral. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2002, 44, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, I. Ion collection by a sphere in a flowing plasma: 2. Non-zero Debye length. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2003, 45, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, I.H. Ion collection by a sphere in a flowing plasma: 3. Floating potential and drag force. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2004, 47, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Vashi, B.; Leung, L. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of current collection by a probe in a magnetized plasma. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1994, 21, 833–836. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Leung, W.; Vashi, B. Potential structure near a probe in a flowing magnetoplasma and current collection. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1997, 102, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Leung, W.; Singh, G.M. Enhanced current collection by a positively charged spacecraft. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2000, 105, 20935–20947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, C.; Groll, R. picFoam: An OpenFOAM based electrostatic Particle-in-Cell solver. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 262, 107853. [Google Scholar]

- Fivaz, M.; Brunner, S.; De Ridder, G.; Sauter, O.; Tran, T.; Vaclavik, J.; Villard, L.; Appert, K. Finite element approach to global gyrokinetic particle-in-cell simulations using magnetic coordinates. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1998, 111, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; He, X.; Lund, D.; Zhang, X. PIFE-PIC: Parallel immersed finite element particle-in-cell for 3D kinetic simulations of plasma-material interactions. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 43, C235–C257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Cao, Y.; He, X.; Peng, E. An implicit particle-in-cell model based on anisotropic immersed-finite-element method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 261, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, A. The fast solution of Poisson’s and the biharmonic equations on irregular regions. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1984, 21, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, A. Fast high order accurate solution of Laplace’s equation on irregular regions. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1985, 6, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, A.; Greenbaum, A. Fast parallel iterative solution of Poisson’s and the biharmonic equations on irregular regions. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comput. 1992, 13, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockney, R.W. The potenitial calculation and some applications. Methods Comput. Phys. 1970, 20, 135. [Google Scholar]

- LeVeque, R.J.; Li, Z. The immersed interface method for elliptic equations with discontinuous coefficients and singular sources. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 1994, 31, 1019–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. An overview of the immersed interface method and its applications. Taiwan. J. Math. 2003, 7, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, T.; Layton, A. On the accuracy of finite difference methods for elliptic problems with interfaces. Commun. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2007, 1, 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, H.; Colella, P. A Cartesian grid embedded boundary method for Poisson’s equation on irregular domains. J. Comput. Phys. 1998, 147, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devendran, D.; Graves, D.; Johansen, H.; Ligocki, T. A fourth-order Cartesian grid embedded boundary method for Poisson’s equation. Commun. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2017, 12, 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, Z.; Macaskill, C. The embedded finite difference method for the Poisson equation in a domain with an irregular boundary and Dirichlet boundary conditions. J. Comput. Phys. 2005, 202, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, Z.; Macaskill, C. The Shortley–Weller embedded finite-difference method for the 3D Poisson equation with mixed boundary conditions. J. Comput. Phys. 2010, 229, 3675–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibou, F.; Fedkiw, R.P.; Cheng, L.T.; Kang, M. A second-order-accurate symmetric discretization of the Poisson equation on irregular domains. J. Comput. Phys. 2002, 176, 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Merriman, B.; Osher, S.; Smereka, P. A simple level set method for solving Stefan problems. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 135, 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortley, G.H.; Weller, R. The numerical solution of Laplace’s equation. J. Appl. Phys. 1938, 9, 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Wasow, W. Discrete approximations to elliptic differential equations. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. ZAMP 1955, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, N.; Yamamoto, T. Superconvergence of the Shortley–Weller approximation for Dirichlet problems. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2000, 116, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lee, H.G.; Kim, J. A fast, robust, and accurate operator splitting method for phase-field simulations of crystal growth. J. Cryst. Growth 2011, 321, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Level set method for computational multi-fluid dynamics: A review on developments, applications and analysis. Sadhana 2015, 40, 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogea, C.S.; Murray, B.T.; Sethian, J.A. Simulating complex tumor dynamics from avascular to vascular growth using a general level-set method. J. Math. Biol. 2006, 53, 86–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revel, A.; Mochalskyy, S.; Montellano, I.M.; Wünderlich, D.; Fantz, U.; Minea, T. Massive parallel 3D PIC simulation of negative ion extraction. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 103302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tang, Q.; Tang, X.z. A Parallel Cut-Cell Algorithm for the Free-Boundary Grad–Shafranov Problem. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 43, B1198–B1225. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.; Whitehead, J.; Thomson, S.; Truscott, T. Error propagation dynamics of PIV-based pressure field calculations: How well does the pressure Poisson solver perform inherently? Meas. Sci. Technol. 2016, 27, 084012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faiella, M.; Macmillan, C.G.J.; Whitehead, J.P.; Pan, Z. Error propagation dynamics of velocimetry-based pressure field calculations (2): On the error profile. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2021, 32, 084005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornet, C.; Kwok, D.T. A new algorithm for charge deposition for multiple-grid method for PIC simulations in r–z cylindrical coordinates. J. Comput. Phys. 2007, 225, 808–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala’yed, O. Modified two-dimensional differential transform method for solving proportional delay partial differential equations. Results Control Optim. 2024, 17, 100499. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wen, J.; Liang, J.; Soekmadji, H.; Liao, S. Physics-informed neural networks for PDE problems: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsalinda, N.; Bakar, M.A.; Harun, F.N.; Surono, S.; Pratama, D.A. A new hybrid approach for solving partial differential equations: Combining Physics-Informed Neural Networks with Cat-and-Mouse based Optimization. Results Appl. Math. 2025, 25, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.N.; Nave, J.C.; Rosales, R.R. A correction function method for Poisson problems with interface jump conditions. J. Comput. Phys. 2011, 230, 7567–7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Becker, M.M.; Loffhagen, D. PIC/MCC simulation of capacitively coupled discharges in helium: Boundary effects. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27, 054002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Zhong, L. PaRO-DeepONet: A particle-informed reduced-order deep operator network for Poisson solver in PIC simulations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.19065. [Google Scholar]

- Strikwerda, J.C. Finite Difference Schemes and Partial Differential Equations; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, R.; Sun, G.; Yang, X.; Zou, F.; You, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, F.; Song, B.; Zhang, G. Investigation of sheath structure in surface flashover induced by high-power microwave. Phys. Plasmas 2024, 31, 053902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Linear Extrapolation | Quadratic Extrapolation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of nodes | error | order | error | order | error | order | error | order |

| 41 × 41 | 8.013 × 10−6 | – | 2.047 × 10−5 | – | 2.3643 × 10−7 | – | 6.7915 × 10−7 | – |

| 81 × 81 | 2.097 × 10−6 | 1.93 | 6.198 × 10−6 | 1.72 | 5.8779 × 10−8 | 2.00 | 1.7224 × 10−7 | 1.82 |

| 161 × 161 | 5.262 × 10−7 | 1.99 | 1.654 × 10−6 | 1.91 | 1.1756 × 10−6 | −4.3 | 9.7126 × 10−4 | −12.5 |

| Linear Extrapolation | Quadratic Extrapolation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of nodes | error | order | error | order | error | order | error | order |

| 41 × 41 | 1.3931 × 10−6 | – | 7.7411 × 10−6 | – | 5.1160 × 10−6 | – | 1.7039 × 10−5 | – |

| 81 × 81 | 3.8876 × 10−7 | 1.84 | 2.8273 × 10−6 | 1.45 | 1.3768 × 10−6 | 1.89 | 4.2559 × 10−6 | 2.00 |

| 151 × 151 | 1.0415 × 10−7 | 2.10 | 8.4515 × 10−7 | 1.92 | 3.6962 × 10−7 | 2.09 | 1.2271 × 10−6 | 1.98 |

| Accurate RHS b | Inaccurate RHS | Modified | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of

Nodes Used | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad |

| 41 × 41 | 5.728 × 10−4 | 2.498 × 10−16 | 3.499 × 10−4 | 6.201 × 10−4 | 5.708 × 10−4 | 2.498 × 10−16 |

| 81 × 81 | 1.446 × 10−4 | 5.551 × 10−16 | 8.386 × 10−5 | 1.482 × 10−4 | 1.446 × 10−4 | 5.551 × 10−16 |

| 161 × 161 | 3.803 × 10−5 | 1.032 × 10−6 | 1.652 × 10−5 | 3.603 × 10−5 | 3.803 × 10−5 | 1.032 × 10−6 |

| Accurate RHS | Inaccurate RHS | Modified | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number

of Nodes | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad |

| 41 × 41 | 2.047 × 10−5 | 6.792 × 10−7 | 7.741 × 10−6 | 1.704 × 10−5 | 1.957 × 10−5 | 8.614 × 10−7 |

| 81 × 81 | 6.198 × 10−6 | 1.722 × 10−7 | 2.827 × 10−6 | 4.256 × 10−6 | 6.039 × 10−6 | 1.652 × 10−7 |

| 151 × 151 | 1.7752 × 10−6 | 4.9798 × 10−8 | 8.4515 × 10−7 | 1.2271 × 10−6 | 1.7526 × 10−6 | 4.8523 × 10−8 |

| Accurate RHS | Inaccurate RHS | Modified | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number

of Nodes | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad |

| 2.007 × 10−4 | 1.113 × 10−5 | 7.294 × 10−5 | 1.768 × 10−4 | 1.880 × 10−4 | 6.039 × 10−6 | |

| 4.939 × 10−5 | 2.348 × 10−6 | 2.076 × 10−5 | 4.621 × 10−5 | 4.779 × 10−5 | 1.747 × 10−6 | |

| 1.284 × 10−5 | 5.281 × 10−7 | 5.724 × 10−6 | 1.187 × 10−5 | 1.263 × 10−5 | 4.599 × 10−7 | |

| Accurate RHS | Inaccurate RHS | Modified | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number

of Nodes | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad | Linear | Quad |

| 7.311× 10−3 | 1.158 × 10−2 | 5.538 × 10−2 | 5.955 × 10−2 | 9.972 × 10−2 | 1.057 × 10−1 | |

| 5.092 × 10−2 | 1.230 × 10−1 | 2.576 × 10−1 | 3.219 × 10−1 | 4.465 × 10−1 | 5.137 × 10−1 | |

| 1.090 | 4.647 | 1.885 | 5.420 | 2.657 | 6.205 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Xiao, T.; Wang, W.; He, B. Numerical Error Analysis of the Poisson Equation Under RHS Inaccuracies in Particle-in-Cell Simulations. Computation 2026, 14, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010013

Zhang K, Xiao T, Wang W, He B. Numerical Error Analysis of the Poisson Equation Under RHS Inaccuracies in Particle-in-Cell Simulations. Computation. 2026; 14(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kai, Tao Xiao, Weizong Wang, and Bijiao He. 2026. "Numerical Error Analysis of the Poisson Equation Under RHS Inaccuracies in Particle-in-Cell Simulations" Computation 14, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010013

APA StyleZhang, K., Xiao, T., Wang, W., & He, B. (2026). Numerical Error Analysis of the Poisson Equation Under RHS Inaccuracies in Particle-in-Cell Simulations. Computation, 14(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation14010013