1. Introduction

Human action recognition (HAR) represents a fundamental challenge in computer vision with extensive applications across diverse domains, including intelligent surveillance systems [

1], human–computer interaction [

2], healthcare monitoring [

3], and autonomous robotics [

4]. While RGB-based action recognition has demonstrated significant progress, it faces several critical limitations: sensitivity to illumination variations [

1], susceptibility to background clutter [

2], and performance degradation under occlusions [

3]. In contrast, skeleton-based representation offers a more robust and efficient alternative by focusing on essential structural information of human poses, providing invariance to appearance changes and background interference while maintaining computational efficiency [

4].

The evolution of skeleton-based action recognition reflects a progression from simple to increasingly sophisticated approaches. Early methods relied on geometric features and statistical descriptors to capture motion patterns, including joint trajectories [

5], relative position encoding [

6], and hierarchical body part analysis [

7]. As deep learning emerged, researchers explored sequential models like RNNs and frame-based CNNs, but these architectures struggled to fully capture the inherent graph structure of the human skeleton, where joints and bones form a natural hierarchical representation of human motion.

The emergence of graph convolutional networks (GCNs) has revolutionized skeleton-based action recognition by providing a natural framework for processing graph-structured data [

8]. The seminal Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (ST-GCN) introduced by Yan et al. [

9] established the foundation for modern skeleton-based methods by simultaneously modeling spatial joint relationships and temporal dynamics through graph convolution operations. ST-GCN constructs spatial–temporal graphs where nodes represent joints across different time frames, and edges encode both spatial anatomical connections and temporal correspondences. This approach significantly outperformed previous methods by effectively capturing the spatial–temporal dependencies inherent in human actions.

Building upon ST-GCN’s foundation, the field has seen rapid advancement through several key innovations. Early improvements focused on enhancing graph topology: Adaptive Graph Convolutional Networks [

10] introduced learnable adjacency matrices to capture dynamic joint relationships, while Dynamic GCN [

11] proposed adaptive graph construction based on joint correlations. Subsequent works explored multi-stream architectures, with AS-GCN [

12] separating actional and structural information, and Shift-GCN [

13] introducing efficient shift operations for lightweight processing. Recent advances have pushed performance further through sophisticated feature learning: CTR-GCN [

14] employs channel-wise topology refinement, InfoGCN [

15] leverages information bottleneck principles for better feature extraction, and MS-GCN [

16] introduces multi-scale graph convolutions for hierarchical feature learning. Despite these advances, several fundamental challenges remain unaddressed in current approaches.

Current approaches face three key challenges in skeleton-based action recognition. First, most existing methods process spatial and temporal information through a single pathway, limiting their ability to capture the distinct characteristics of joint configurations and motion patterns [

14,

15]. This unified processing can blur important modality-specific features that require specialized treatment. Second, as sequence lengths grow, memory requirements become prohibitive due to the quadratic complexity of attention mechanisms [

17,

18], restricting the model’s ability to handle long-term dependencies. Third, the lack of explicit interaction between spatial and temporal features means that valuable cross-modal patterns may be missed, potentially reducing recognition accuracy for complex actions that depend on both pose and motion cues [

19].

To address these limitations, we introduce the dual-path cross-attention GCN (DPCA-GCN). Our architecture offers three key innovations: (1) dedicated spatial and temporal pathways, each optimized for its specific domain; (2) memory-efficient bidirectional cross-attention that enables selective information exchange between pathways; and (3) an adaptive gating mechanism that automatically balances spatial and temporal contributions based on action context. Extensive experiments on the NTU RGB+D 60 and NTU RGB+D 120 datasets demonstrate that DPCA-GCN achieves performance comparable with recent state-of-the-art methods, validating the effectiveness of explicit dual-path modeling and targeted cross-modal fusion for skeleton-based action recognition. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose a novel dual-path architecture that explicitly separates spatial and temporal feature extraction through specialized pathways, enabling modality-specific learning that better captures the distinct characteristics of joint configurations and motion dynamics.

We introduce a memory-efficient bidirectional cross-attention mechanism that reduces complexity from to while enabling rich information exchange between spatial and temporal pathways at multiple processing stages.

We design an adaptive gating module that learns action-specific fusion weights, dynamically balancing spatial and temporal contributions according to input characteristics rather than using fixed fusion strategies.

We conduct extensive experiments and ablation studies on NTU RGB+D 60 and NTU RGB+D 120 datasets, achieving competitive joint-only performance (88.72%/94.31% and 82.85%/83.65%) with significantly lower computational complexity compared to multi-modal approaches, along with exceptional top-5 accuracies (96.97%/99.14% and 95.59%/95.96%).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in skeleton-based action recognition and graph neural networks.

Section 3 details our proposed DPCA-GCN approach.

Section 4 presents experimental results and analysis. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future work.

2. Related Work

The field of skeleton-based human action recognition has evolved significantly, particularly in the past five years, through innovations in graph neural networks, attention mechanisms, and efficient processing techniques. This section systematically reviews the key developments that inform our DPCA-GCN approach.

2.1. Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton Data

Modern skeleton-based action recognition has been fundamentally shaped by advances in graph convolutional networks, which provide natural frameworks for modeling the structural relationships inherent in human skeletal data. Graph topology enhancement represents a critical advancement in this domain, with several key methodological developments emerging.

Chen et al. [

14] introduced CTR-GCN with channel-wise topology refinement, demonstrating that adaptive adjacency matrices significantly improve performance through better graph representation learning. This approach addresses the limitation of fixed graph topologies by enabling networks to learn task-specific spatial relationships between joints. Building upon similar principles, Chi et al. [

15] proposed InfoGCN, which applies information bottleneck theory to enhance feature discriminability while reducing redundancy in graph representations. These topology-aware methods established the importance of adaptive graph construction, though they maintained unified processing pathways for spatial and temporal information.

Multi-scale feature learning has emerged as another fundamental technique for capturing hierarchical motion patterns. Kilic et al. [

16] developed MS-GCN with multi-scale convolutions to capture features at different granularities, enabling models to understand both fine-grained joint movements and broader action patterns. Liu et al. [

20] proposed TSGCNeXt, combining dynamic and static graph convolutions for efficient long-term modeling. Their approach demonstrates the effectiveness of hybrid strategies that leverage both fixed skeletal structure and adaptive relationships.

Recent developments have focused on advanced architectural designs and processing mechanisms. Zhou et al. [

21] introduced BlockGCN, which redefines topology awareness through block-wise processing to better capture local and global motion patterns. Myung et al. [

22] proposed deformable graph convolutions that dynamically adjust to varying skeleton structures, showing remarkable adaptability to different body configurations and motion styles. Most recently, Li and Li [

23] proposed DF-GCN (2025), a lightweight dynamic dual-stream network that explicitly separates spatial and temporal processing with dynamic graph construction, underscoring the persistent value of dual-stream architectures. Similarly, Chen et al. [

24] introduced a two-stream GCN–Transformer hybrid (2025) combining graph convolutions with transformer attention, validating the effectiveness of hybrid strategies for balancing local structural modeling and global context capture. Our own recent work [

25] further validates the hybrid approach by demonstrating the efficacy of attention-inflated 3D architectures for capturing complex action dynamics.

Beyond skeleton-specific methods, the broader action recognition literature provides valuable insights. Ramanathan et al. [

26] developed a mutually reinforcing motion–pose framework for pose-invariant recognition from RGB videos, demonstrating that explicit modeling of pose and motion as separate but interacting components improves robustness. In our comparative study of I3D and SlowFast networks [

27], we observed similar trade-offs between spatial and temporal modeling in video data, reinforcing the need for architectures that can effectively balance these modalities. While their work focuses on RGB-based recognition without explicit skeletons, it validates our core hypothesis that motion and pose (analogous to our temporal and spatial features) benefit from separate processing with explicit interaction mechanisms.

A common characteristic across existing graph-based methods is their reliance on unified or sequential pathways for processing spatial and temporal information. While effective, this architectural choice constrains the ability to capture modality-specific patterns that require specialized treatment. Our DPCA-GCN addresses this limitation through explicit dual-path processing with bidirectional cross-attention fusion, enabling domain-specific optimizations while maintaining cross-modal coherence.

2.2. Attention and Transformer-Based Models

The integration of attention mechanisms into skeleton-based models has progressed from simple hybrid approaches to sophisticated transformer architectures. Early hybrid approaches focused on enhancing GCN capabilities. Plizzari et al. [

28] developed a spatial–temporal attention module that selectively emphasizes informative joints and frames. Si et al. [

29] proposed AGC-LSTM, augmenting LSTM cells with joint-level attention to capture long-term dependencies in motion sequences.

Pure-attention architectures, primarily Transformer-based models, emerged as powerful alternatives to GCN-based approaches. Plizzari et al. [

30] introduced ST-TR, which innovatively tokenizes joint–frame pairs through a Transformer encoder, enabling direct modeling of global spatio-temporal relationships. Shi et al. [

31] developed DSTA-Net with factorized attention mechanisms, separately processing spatial and temporal information with decoupled positional encodings. This design significantly reduced computational complexity while maintaining high accuracy. Ahn et al. [

32] proposed STAR-Transformer, introducing a sparse neighborhood attention pattern that achieves linear computational complexity without sacrificing performance.

However, transformer-based architectures faces significant limitations for skeleton-based recognition: (1) Loss of structural inductive bias—transformers treat skeleton as unordered token sets, discarding the natural graph topology that GCNs explicitly model. This requires substantially more training data to learn spatial relationships that GCNs encode architecturally. (2) Computational inefficiency—despite optimization efforts, attention mechanisms remain memory-intensive ( or for efficient variants), limiting their applicability to long sequences or resource-constrained scenarios. (3) Difficulty in incorporating domain knowledge—skeletal topology (bone connections, body part hierarchies) cannot be naturally integrated into pure-attention frameworks, unlike GCNs where adjacency matrices encode such priors.

Recent transformer-based innovations have focused on efficiency and scalability. Liu et al. [

20] introduced TSGCNeXt in 2023, combining dynamic and static graph convolutions within a transformer framework for efficient long-term modeling. Their approach particularly excels at capturing both consistent skeletal structure and varying temporal dynamics. The influence of video-centric transformers has been significant, with Bertasius et al. [

33] proposing TimeSformer, Arnab et al. [

34] developing ViViT, and Fan et al. [

35] introducing MViT. These works have inspired various efficient variants using techniques like pooled attention and chunk-based processing, addressing the computational challenges of processing long sequences.

Our approach leverages the complementary strengths of both paradigms: GCNs provide efficient structural modeling with built-in skeletal priors, while transformers enable flexible global context capture. This hybrid strategy has proven effective across recent methods [

20,

24], suggesting that combining structural inductive biases with attention mechanisms offers superior efficiency–accuracy trade-offs compared to transformer-based approaches.

2.3. Multi-Stream Spatio-Temporal Frameworks

The concept of processing complementary motion aspects through separate streams has proven highly effective. Feichtenhofer et al. [

36] pioneered this approach with SlowFast networks for RGB-based recognition, processing slow semantic features and fast motion patterns in parallel pathways. In the skeleton domain, Liu et al. [

37] proposed Disentangled-ST, featuring independent spatial and temporal encoders whose outputs are strategically fused. This separation allows each encoder to specialize in its respective domain while maintaining information exchange through careful fusion strategies.

Recent work has explored increasingly sophisticated multi-stream architectures. Duan et al. [

38] developed DG-STGCN, employing dynamic graphs in the spatial stream and grouped convolutions in the temporal stream, achieving state-of-the-art performance through specialized processing pathways. Wang et al. [

39] proposed SpSt-GCN, introducing novel information exchange mechanisms between spatial and structural streams that enhance the model’s ability to capture complex motion patterns.

The latest advancements focus on optimal stream interaction and fusion. Zhou et al. [

21] introduced BlockGCN in 2024, redefining topology awareness through block-wise graph processing that better captures local and global motion patterns. Their approach demonstrates superior performance on actions requiring understanding of both fine-grained movements and overall body coordination.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview and Architectural Rationale

Most Spatial–Temporal GCN models process joint configuration (space) and motion dynamics (time) in a single, tightly coupled stream, making it difficult to learn modality-specific patterns. DPCA-GCN addresses this limitation with two dedicated pathways—spatial and temporal—that communicate through an efficient bidirectional cross-attention mechanism and are mixed by an adaptive gate.

Our architectural choices directly address the three identified limitations:

(1) Dual-Path Design for Modality-Specific Learning: Spatial and temporal features have fundamentally different characteristics—spatial features capture joint relationships within frames (graph-structured), while temporal features capture motion dynamics across frames (sequence-structured). Processing these jointly in a single pathway forces a compromised representation. Our dual-path design allows (a) the spatial pathway to use graph convolution optimized for skeletal topology, and (b) the temporal pathway to use 1D convolution optimized for sequential dependencies. This separation follows the multi-stream paradigm proven effective in video understanding [

36], where specialized processing of different modalities yields superior performance compared to unified architectures.

(2) Chunked Attention for Memory Efficiency: Standard attention mechanisms require memory for sequence length L, making them impractical for skeleton sequences where (frames × joints). For typical settings (, resulting in tokens per sequence), the quadratic memory dependency of full attention poses a significant computational barrier. Our chunked mechanism addresses this by dividing queries into chunks while maintaining full key–value access, thereby reducing the memory complexity to where C is chunk size. This innovation enables the processing of long sequences without sacrificing global context, unlike simpler sliding window approaches that inherently lose long-range dependencies.

(3) Bidirectional Cross-Attention for Cross-Modal Interaction: Simply concatenating spatial and temporal features (early fusion) or averaging their predictions (late fusion) fails to capture their intricate dependencies. For example, recognizing “drinking” requires understanding both the hand trajectory (temporal) and hand–mouth spatial proximity (spatial) simultaneously. Bidirectional attention enables each pathway to query the other: spatial features can attend to relevant temporal patterns and vice versa, creating rich cross-modal representations that neither pathway alone could produce.

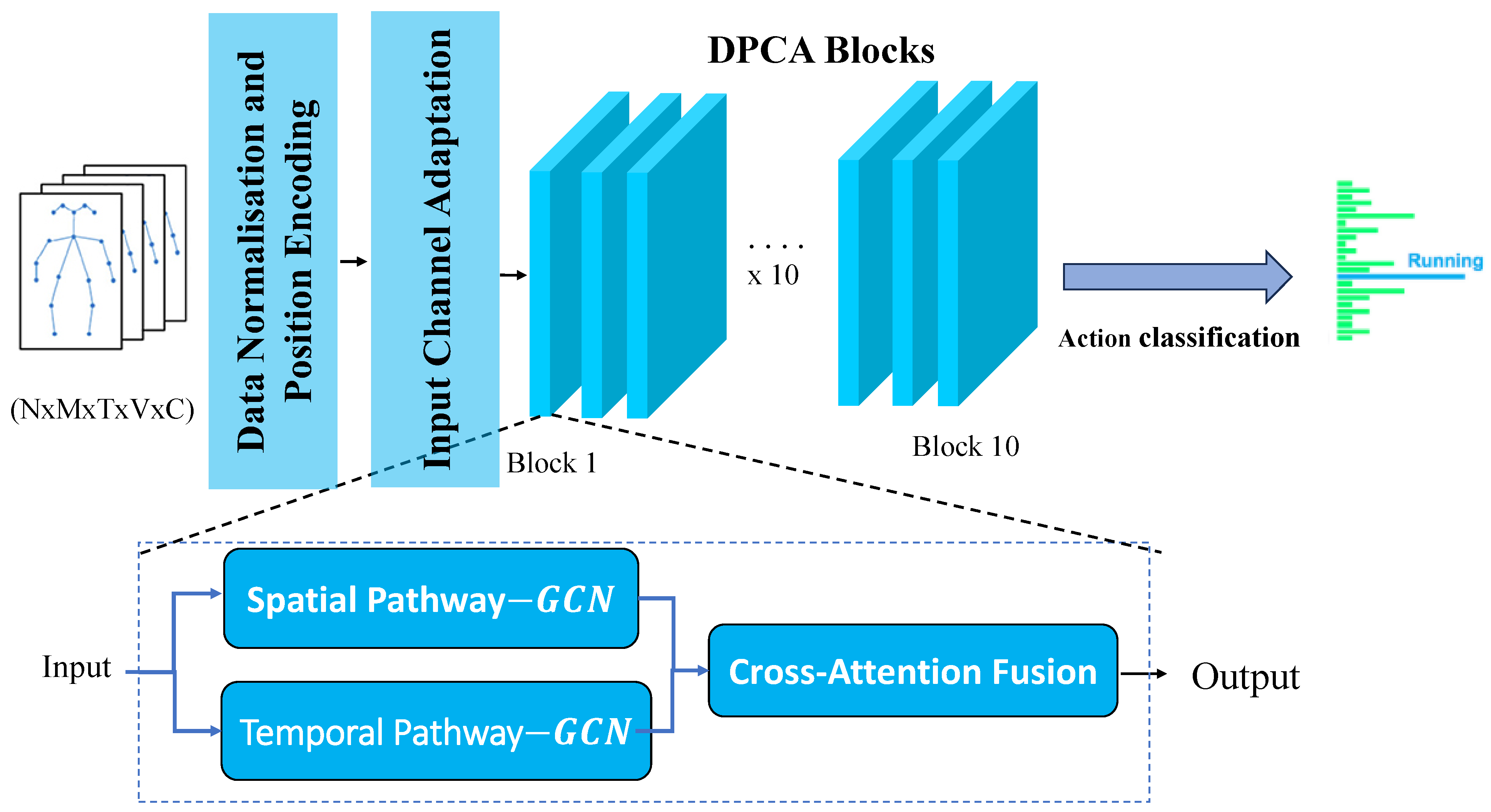

Figure 1 shows the complete pipeline: an input skeleton sequence is normalized, fed to both paths, fused at each of the

L stacked DPCA blocks, and finally aggregated by global average pooling and a linear classifier.

3.2. Dual-Path Feature Extraction

Given features

at block

l, the spatial pathway performs graph convolution to aggregate neighboring joints:

where

is a learnable adjacency matrix and

denotes ReLU activation. The features are then processed by a spatial transformer:

Similarly, the temporal pathway applies 1-D convolution along the time axis, followed by a temporal transformer:

where ∗ denotes 1-D temporal convolution.

3.3. Transformer Cell (Shared)

Both spatial and temporal transformers adopt the pre-LN design of [

40]:

where LN is LayerNorm, MHA is

h-head self-attention, and FFN is a two-layer perceptron with expansion ratio 4. This cell is parameter-shared across time in the spatial path and across joints in the temporal path.

3.4. Bidirectional Chunked Cross-Attention

Figure 2 details one DPCA block. Linear projections produce

and

. Queries are partitioned into non-overlapping chunks of length

C:

where

ChunkAttn computes scaled dot-product attention

inside each chunk, reducing the memory footprint from

to

while still letting every query view the entire key/value set.

3.5. Adaptive Gate

The adaptive gate determines the optimal combination of spatial and temporal features based on action context. This module addresses a key limitation of existing multi-stream methods: their inability to dynamically adjust the importance of spatial vs. temporal information according to action characteristics.

Motivation: Different actions exhibit varying spatial–temporal characteristics. For instance, “reading” or “writing” are relatively static with high spatial discriminability (hand-book configuration) but limited temporal dynamics. Conversely, “walking” or “running” show consistent spatial patterns but strong temporal signatures. A fixed fusion strategy cannot optimally handle this diversity.

Implementation: To derive the context-aware fusion weights, the enhanced spatial and temporal feature tensors,

and

(where residual connections ensure pathway-specific information is preserved after cross-attention), are first concatenated. This combined representation is then subjected to global average pooling to extract a compact global context vector

:

A two-layer MLP with reduction ratio

(inspired by SENet [

14] but adapted for dual-stream fusion) produces channel-wise attention weights:

where

and

(enforced by softmax). The final fusion is computed as

The MLP learns to map input-dependent global statistics to fusion weights. For spatially discriminative actions (e.g., “pointing”), the network learns , emphasizing spatial features. For temporally discriminative actions (e.g., “jumping”), it learns . This adaptation happens per sample and per layer, allowing hierarchical refinement of spatial–temporal balance as features become more abstract in deeper layers.

While adaptive fusion has been explored in multi-modal learning, our formulation uniquely operates on cross-attention-enhanced features rather than raw pathway outputs. This enables the gate to reason about cross-modal interactions (, ) when determining fusion weights, creating a feedback loop where attention patterns inform fusion decisions.

3.6. Positional Encoding and Network Depth

To keep joint order and frame chronology, we inject learnable spatial and temporal embeddings at the input:

We stack DPCA blocks; Blocks 5 and 8 double channel width and down-sample time by 2, enlarging the receptive field.

The complete forward pass of DPCA-GCN is summarized in Algorithm 1. Following recent efficient implementations [

17,

41], we optimize the processing pipeline through careful data normalization, parallel pathway processing, and memory-efficient attention computation. The algorithm consists of four main stages:

Input Processing: The input skeleton sequence undergoes data normalization and positional encoding injection, similar to [

40] but adapted for spatial–temporal data.

Dual-Path Processing: Each DPCA block processes spatial and temporal information in parallel pathways, inspired by [

36] but extended for skeleton data.

Cross-Modal Fusion: The bidirectional chunked attention mechanism enables efficient information exchange while maintaining linear memory complexity [

18].

Progressive Feature Aggregation: Multi-scale feature learning is achieved through strategic temporal downsampling and channel inflation, following insights from [

19].

| Algorithm 1 Forward Pass of DPCA-GCN. | |

- Require:

Skeleton sequence

| ▹ N: batch, T: frames, V: joints, C: channels |

- Ensure:

Logits

| ▹ cls: number of action classes |

- 1:

| ▹ Input normalization |

- 2:

| ▹ Add positional encodings |

- 3:

| ▹ Initialize pathways |

- 4:

for to do

| ▹ Process L DPCA blocks |

- 5:

Spatial GCN + Transformer

| ▹ Spatial pathway via Equation (1) |

- 6:

Temporal Conv + Transformer

| ▹ Temporal pathway via Equation (3) |

- 7:

Compute bidirectional cross-attention

| ▹ Cross-modal exchange |

- 8:

Adaptive gate fusion

| ▹ Adaptive fusion via Equation (12) |

- 9:

if then

| ▹ Multi-scale processing |

- 10:

Apply temporal downsampling and channel inflation

| |

- 11:

end if

| |

- 12:

| ▹ Update features |

- 13:

end for

| |

- 14:

| ▹ Global pooling |

- 15:

| ▹ Classification |

4. Results

4.1. Datasets

We evaluate our approach on two widely recognized action recognition datasets: NTU RGB+D 60 [

42] and NTU RGB+D 120 [

43]. Both datasets are captured using Microsoft Kinect V2 sensors, providing 3D skeletal data with 25 body joint coordinates captured at 30 fps from three camera viewpoints.

4.1.1. NTU RGB+D 60

NTU RGB+D 60 contains 56,880 skeleton sequences across 60 distinct action categories, encompassing 40 daily activities, 9 healthcare-related actions, and 11 interactive behaviors. Two standard evaluation protocols are used:

Cross-subject (X-Sub): Training set contains 40,320 sequences from 20 subjects (IDs: 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 25, 27, 28, 31, 34, 35, 38). Testing set contains 16,560 sequences from the remaining 20 subjects. No validation set is explicitly defined; we use the official test set for final evaluation.

Cross-view (X-View): Training set uses 37,920 sequences from camera views 2 and 3. Testing set uses 18,960 sequences from camera view 1 (frontal view). Following standard practice [

9,

14], we perform model selection using validation accuracy on a held-out subset of training data (10% randomly sampled), then report final results on the official test set.

4.1.2. NTU RGB+D 120

NTU RGB+D 120 extends the dataset to 120 action classes with 114,480 total sequences. Two evaluation protocols are employed:

Cross-subject (X-Sub): Training set contains 63,026 sequences from 53 subjects (IDs 1–53 excluding specific held-out subjects). Testing set contains 50,922 sequences from 53 different subjects (IDs 54–106). Validation is performed on 10% of training data following standard practice.

Cross-setup (X-Setup): Training set uses 54,471 sequences from even-numbered setup IDs (16 setups with different camera configurations and environmental conditions). Testing set uses 59,477 sequences from odd-numbered setup IDs (16 setups). This protocol evaluates generalization across different recording conditions.

Training–Validation–Testing Split: Following established protocols [

9,

14,

15], we use the official train–test splits defined by the dataset creators. For hyperparameter tuning and early stopping, we sample 10% of official training sequences as a validation set (stratified by action class to maintain class balance). Final reported accuracies are computed on the official test sets without any validation data leakage.

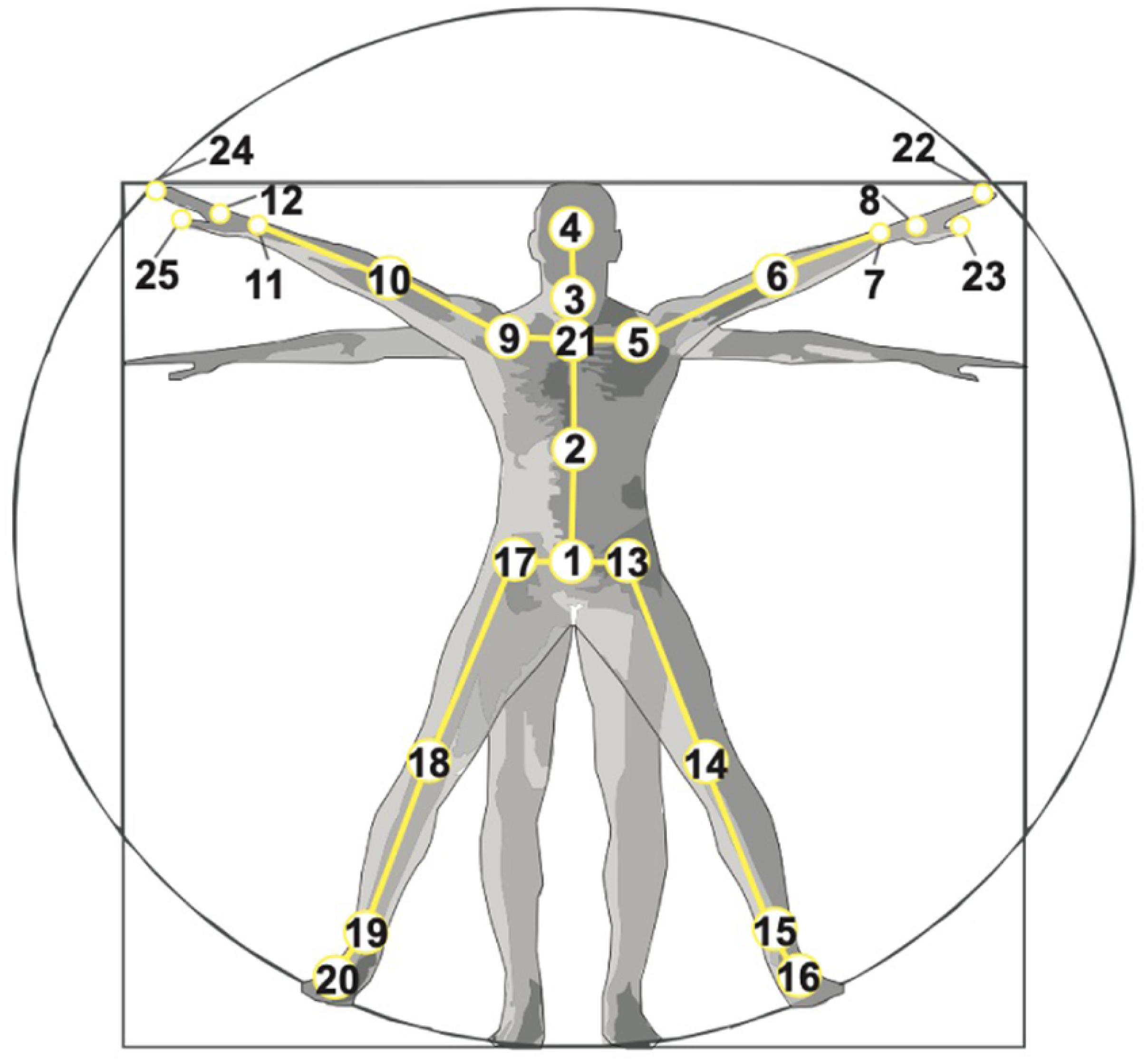

Figure 3 illustrates representative action samples from the NTU RGB+D 60 and NTU RGB+D 120 datasets, highlighting the diversity of actions and recording conditions. In addition,

Figure 4 shows the configuration and indexing of the 25 body joints used to construct the skeleton representations in both datasets.

4.2. Implementation Details

Our experiments are implemented using PyTorch 1.10.0 with mixed-precision training for enhanced computational efficiency. The DPCA-GCN model is optimized using AdamW with initial learning rate 0.001 and weight decay 0.05. Training employs Cross-entropy loss with label smoothing (smoothing factor 0.1).

We utilize an effective training batch size of 32 (8 samples per GPU with five-step gradient accumulation). The learning rate follows cosine annealing, decreasing from the initial rate to over 45 epochs, including a 12-epoch warmup period. Sequences are uniformly sampled to a fixed length of 64 frames and undergo initial 3D joint coordinate normalization.

Handling Missing and Occluded Joints: Skeleton sequences obtained from depth sensors, such as NTU RGB+D, frequently contain instances of missing or unreliable joint coordinates due to factors like occlusions, sensor limitations, or inaccuracies in pose estimation. Our preprocessing pipeline primarily handles core data preparation steps, including normalizing 3D joint coordinates (PreNormalize3D module) and ensuring uniform sequence lengths by sampling frames (UniformSampleFrames module).

For any joints that are reported as missing or entirely occluded within the raw input data (e.g., if their coordinates are effectively zeros), our current pipeline implicitly treats these values as zeros after normalization. This means the model processes a sequence where occluded joints effectively contribute zero spatial information. Crucially, our DPCA-GCN architecture, with its transformer-based attention mechanisms, offers an inherent capacity for robustness to such incomplete inputs. These mechanisms can dynamically learn to adaptively weigh or de-emphasize unreliable or zero-valued joint information by adjusting attention scores, effectively learning to infer or ignore patterns from the remaining visible joints.

4.3. Results and Discussion

4.3.1. Performance Evaluation

Table 1 presents comprehensive evaluation results of DPCA-GCN on both datasets. On NTU RGB+D 60, our model achieves 88.72% top-1 accuracy on cross-subject and 94.31% on cross-view protocols, with impressive top-5 accuracies of 96.97% and 99.14%, respectively. On NTU RGB+D 120, the model maintains competitive performance with 82.85% and 83.65% top-1 accuracies, with corresponding top-5 accuracies of 95.59% and 95.96%.

Figure 5 illustrates the training dynamics of DPCA-GCN on the NTU RGB+D 60 X-Sub protocol, including the evolution of the cross-entropy loss and the top-1 and top-5 accuracies across training epochs.

4.3.2. Comparative Analysis

Table 2 compares DPCA-GCN with state-of-the-art methods, organized by modality usage to highlight architectural advantages. Our approach demonstrates competitive performance within the joint-only processing paradigm while introducing significant architectural innovations.

The comparative analysis reveals that DPCA-GCN achieves competitive performance within the joint-only processing paradigm while introducing significant architectural innovations. Our model demonstrates superior performance compared to most existing joint-only methods, particularly excelling in cross-setup evaluation (83.65%) where it surpasses ST-TR (83.4%) and approaches the performance of multi-modal methods with substantially lower computational complexity.

4.3.3. Computational Complexity Analysis

A key advantage of DPCA-GCN is its computational efficiency.

Table 3 compares model complexity, inference time, and memory usage.

Attention Mechanism Complexity: Our chunked cross-attention achieves memory complexity instead of for standard attention, where L is sequence length and C is chunk size. For typical settings ( tokens, ), this reduces memory from M to K elements per attention operation—a 12.5× reduction.

Multi-Modal Comparison: While multi-modal methods (CTR-GCN, InfoGCN) achieve 3-4% higher accuracy, they process four modalities (Joint, Bone, Joint Motion, Bone Motion) requiring 4× forward passes and 4× model parameters. DPCA-GCN achieves 88.72% accuracy with a single modality, offering superior efficiency for resource-constrained deployment scenarios.

4.3.4. Architectural Advantages and Analysis

The effectiveness of DPCA-GCN stems from three key architectural innovations that address fundamental limitations in existing approaches:

Specialized Dual-Path Processing: Unlike conventional approaches that process spatial and temporal information sequentially, our dual-path architecture enables specialized processing for each modality. The spatial pathway effectively captures intra-frame joint relationships through graph convolution and spatial transformers, while the temporal pathway models inter-frame dynamics using temporal convolution and temporal transformers. This separation allows each pathway to optimize for domain-specific characteristics while maintaining system coherence.

Memory-Efficient Cross-Attention: Our chunked cross-attention mechanism addresses practical memory constraints while providing regularization benefits. By achieving O(L·C) complexity instead of O(L2) required by standard transformer approaches, the model can process longer sequences without memory limitations. The bidirectional information exchange enables spatial features to attend to temporal features and vice versa, capturing complex spatio-temporal correlations missed by sequential processing methods.

Adaptive Feature Integration: The learnable gating mechanism automatically determines optimal balance between spatial and temporal features for different actions. This dynamic adaptation proves particularly beneficial for actions with varying spatial–temporal characteristics, as evidenced by consistent performance across diverse evaluation protocols.

The efficiency–accuracy trade-off analysis demonstrates that while multi-modal methods achieve 3–4% higher accuracy through 4× computational complexity, DPCA-GCN provides exceptional value within the joint-only paradigm. Our exceptional top-5 performance (99.14% on cross-view evaluation) indicates that the model effectively captures the most relevant action patterns, suggesting strong practical applicability for real-world deployment scenarios where computational efficiency is crucial.

4.4. Ablation Studies

To validate the effectiveness of each architectural component, we conduct comprehensive ablation studies on NTU RGB+D 60 X-Sub protocol.

Table 4 presents the results.

4.4.1. Impact of Core Components

Cross-Attention Mechanism: We compare our bidirectional cross-attention with a baseline that simply concatenates spatial and temporal features without attention-based fusion. Removing cross-attention (No Cross-Attention variant) results in 87.95% accuracy, demonstrating that explicit cross-modal information exchange is crucial. Without cross-attention, spatial and temporal pathways operate independently until final fusion, failing to capture their intricate dependencies.

Bidirectional vs. Unidirectional Attention: We evaluate unidirectional cross-attention where only spatial features attend to temporal features ( only), mimicking asymmetric fusion strategies in prior work. The Unidirectional variant achieves 87.81% accuracy. The 0.91% drop compared to bidirectional attention confirms that symmetric information exchange is beneficial—temporal features also benefit from attending to spatial patterns, not just vice versa.

Adaptive Gate: Disabling the adaptive gate and using fixed fusion weights () yields 86.27% accuracy (No Adaptive Gate). This 2.45% degradation validates our hypothesis that action-specific spatial–temporal balancing improves recognition, as different actions benefit from different modality emphases.

Dual-Path Architecture: We implement a Single-Path baseline that processes spatial and temporal information jointly through a single unified pathway (similar to standard ST-GCN architecture). This variant achieves 84.59%, confirming that explicit pathway separation enables modality-specific learning that improves performance.

4.4.2. Chunk Size Analysis

Our chunked attention mechanism introduces a trade-off between memory efficiency and attention granularity.

Table 5 presents results across different chunk sizes.

Observations: Our analysis of different chunk sizes reveals the following: (1) chunk sizes 64 and 128 achieve similar accuracy, indicating that moderate chunking does not sacrifice model capacity; and (2) smaller chunks (32) underperform due to their limited attention scope within chunks.

4.5. Limitations and Failure Case Analysis

While DPCA-GCN demonstrates competitive performance, several limitations warrant discussion:

Performance Gap vs. Multi-Modal Methods: Our joint-only approach achieves 88.72% on NTU 60 X-Sub, while multi-modal methods like InfoGCN reach 93.0%—a 4.3% gap. This highlights an inherent limitation: single-modality processing cannot fully capture the richness of multi-modal representations. Bone structure and motion velocity provide complementary cues that joint coordinates alone cannot encode. Failure cases: predominantly occur in action pairs with similar joint trajectories but different motion speeds (e.g., “walking” vs. “running”) or fine-grained hand manipulations where bone-level features are more discriminative than joint positions.

Long-Range Temporal Dependencies: Despite chunked attention improving efficiency, our model processes sequences of 64 frames due to memory constraints. Actions spanning longer durations may have critical temporal patterns outside this window. Failure analysis: reveals that our model struggles with actions having extended preparation phases (e.g., “taking off jacket”—the critical discriminative motion occurs after initial frames that resemble “wearing jacket”).

Computational Cost vs. Lightweight Models: While more efficient than multi-modal methods, DPCA-GCN is still heavier than lightweight alternatives like Shift-GCN [

13] due to transformer components.

Confusion Matrix and Misclassification Analysis: We perform detailed per-class analysis to identify systematic failure modes. The key findings are visualized in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The most frequently misclassified action pairs and their underlying causes are as follows.

The misclassification patterns are further analyzed across key action categories.

Table 6 highlights the most frequent confusion pairs, while specific insights are drawn from detailed category analysis:

Interaction Actions (avg. 84.02% accuracy): This category, including actions like handshaking, hugging, punching, and kicking, often involves subtle inter-person dynamics or similar arm trajectories. Shaking hands vs. walking towards: 17.6% confusion rate—both involve similar arm trajectories, and distinguishing requires modeling subtle interaction patterns. Hugging vs. touch pocket: 11.1% confusion—spatial proximity patterns can be similar; temporal dynamics and specific contact points are key differentiators. Punch/slap vs. kicking: 19.4% confusion—these aggressive actions can share similar preparatory or follow-through motions.

Fine-Grained Hand Manipulations (avg. 85.61% accuracy): Actions requiring precise hand movements, such as writing or typing, present specific challenges. Writing vs. tear up paper: 22.0% confusion—both show similar hand-to-surface or hand–object manipulation, and without finer joint details (25-joint skeleton only includes wrist), our model struggles to distinguish grip and tool use patterns. Type on a keyboard vs. phone call: 16.2% confusion—repetitive hand motions can appear visually similar, especially without explicit object interaction cues.

Gross Motor Patterns (avg. 87.84% accuracy): This category encompasses actions involving larger body movements like sitting, standing, walking, and running. Sit down vs. stand up: 10.8% confusion—spatial endpoint states are similar; temporal direction (forward vs. backward time) is the primary distinguisher. Walking vs. running: (This common confusion is not explicitly in the top 20 list but is a general challenge for gross motor patterns where velocity is key). Misclassifications here often stem from subtle velocity differences that joint positions alone encode weakly.

Single-Person Daily Activities (avg. 87.81% accuracy): This broad category covers a wide range of everyday actions. Misclassifications here are often subtle and specific, requiring finer distinction of context and interaction with objects. Drink water vs. throw: 3.4% confusion—actions with shared initial poses but divergent subsequent movements can be challenging. Eat meal vs. reading: 2.9% confusion—these involve static or repetitive upper body movements that can appear similar without rich object context.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we introduced DPCA-GCN, a novel dual-path cross-attention framework for skeleton-based human action recognition that addresses fundamental limitations in existing approaches. Our key innovations include a dual-path architecture that processes spatial and temporal information through specialized pathways, a memory-efficient cross-attention mechanism that enables effective cross-modal feature fusion, and adaptive gating for optimal feature combination.

Extensive experiments on NTU RGB+D 60 and NTU RGB+D 120 datasets demonstrate that DPCA-GCN achieves competitive performance with joint-only accuracies of 88.72%/94.31% and 82.85%/83.65%, respectively, while maintaining significantly lower computational complexity compared to multi-modal approaches. The exceptional top-5 performance indicates strong practical applicability for real-world deployment scenarios.

Building upon DPCA-GCN’s strengths, future work will explore enhancing its capabilities across several promising avenues. Primarily, we aim to extend the dual-path framework to seamlessly integrate additional modalities, such as bone and motion data, thereby narrowing the performance gap with state-of-the-art multi-modal methods while rigorously preserving architectural efficiency. Concurrently, we plan to investigate advanced dynamic graph construction techniques, allowing the model to adapt its understanding of joint relationships based on the specific action context, and to develop hierarchical temporal modeling pathways capable of capturing both fine-grained, short-term movements and the broader, long-range structure of complex actions. These directions promise to further unlock DPCA-GCN’s potential for robust and nuanced action recognition.