Towards 6G: A Review of Optical Transport Challenges for Intelligent and Autonomous Communications

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Key 6G Requirements for Optical Transport

- Throughput: Peak per-device data rates are expected to reach or exceed 1 terabit per second (Tbps), with user-experienced data rates sustained in the range of hundreds of gigabits per second (Gbps). This represents an increase of 50–100 times compared with peak 5G capabilities. Specific applications, such as high-fidelity holographic communications, may require even greater capacities, potentially exceeding 4 Tbps per stream [4].

- Latency: End-to-end (E2E) latency must be drastically reduced from the millisecond (ms) range typical of 5G URLLC to microsecond (µs) levels, targeting 10–100 µs [5]. This constitutes a 10- to 100-fold reduction compared with 5G [6]. Moreover, not only must average latency be low, but it must also be deterministic, with minimal variation (jitter) [7].

- Reliability: The levels of reliability required for hyper-reliable and low-latency communications (HRLLC or eRLLC in 6G terminology) reach extremely high thresholds, with transmission success rates between 99.9999% and 99.9999999%—commonly referred to as “seven to nine nines”.

- Connection Density: The 6G network must be capable of supporting a massive density of simultaneously connected devices, potentially ranging between 107 and 108 devices per square kilometre [5]. This is fundamental for the Internet of Everything (IoE).

- Synchronisation: The precise coordination of complex network operations, such as advanced beamforming, distributed computing, and cooperative radio interfaces, demands time synchronisation accuracy at the nanosecond (ns) level across the optical network [8].

- Energy Efficiency: A significant increase in energy efficiency, measured in bits transmitted per joule of consumed energy, is expected—with improvement targets of up to 100 times compared with 5G [5]. It is important to note, however, that higher efficiency per bit does not necessarily guarantee a reduction in the network’s total energy consumption, given the exponential growth expected in traffic volume [9].

- AI-Native Intelligence: A fundamental and transversal requirement is that the 6G network architecture must be inherently intelligent (AI-Native). This means that Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are not merely overlaid applications but are deeply integrated into the fabric of the network—from design to operation and optimisation—including the optical transport layer [10].

1.2. Second-Order Perspective: Beyond Connectivity

2. Evolution of Optical Network Architecture for 6G (x-Haul)

2.1. Limitations of the Current 5G Optical Infrastructure

2.1.1. G Fronthaul (CPRI/eCPRI over Ethernet/PON):

- Capacity: The Common Public Radio Interface (CPRI) protocol, widely used in 4G and early 5G deployments, has a practical bandwidth limit of approximately 24 Gbps per link and does not scale efficiently to support massive MIMO configurations and the much wider channel bandwidths anticipated for 6G [14]. The enhanced CPRI (eCPRI) protocol, designed to be more bandwidth-efficient by transporting data in the frequency domain or through higher functional splits, reduces the load but may still prove insufficient for the projected demands of hundreds of Gbps or even Tbps per cell site in 6G [15]. It is estimated that 6G fronthaul could require more than 500 Gbps per individual cell, aggregating traffic that exceeds 1 Tbps or even 10 Tbps in sites hosting multiple radio units (RUs) [16].

- Latency and Jitter: Standard Ethernet, while flexible and cost-effective, lacks inherent mechanisms to guarantee deterministic latency. The variability in packet delay (Packet Delay Variation—PDV), or jitter, introduced by conventional Ethernet switching, is incompatible with the microsecond-level latency requirements and temporal stability necessary for 6G fronthaul [14]. Passive Optical Network (PON) solutions based on time-division multiplexing (TDM-PON), such as GPON or XGS-PON, although efficient for backhaul or FTTH applications, introduce significant latency (>100 µs) due to their dynamic bandwidth allocation (DBA) mechanisms, making them unsuitable for the most stringent 6G fronthaul segments [16].

- Synchronisation: The inherent delay variation in conventional packet-based Ethernet networks poses a major challenge for accurate timing transfer, which is essential to achieve the nanosecond-level synchronisation required by 6G [14]. Although protocols such as Precision Time Protocol (PTP) over Ethernet can improve accuracy, achieving the nanometric stability and precision required across multiple packetised network hops remains difficult [14]. A maximum time error of approximately 3 µs is required in O-RAN interfaces, and potentially much lower for advanced 6G functions [8].

- 5G PON: Current generations of PON (GPON, XGS-PON, and even the emerging 25G-PON) were not designed to deliver the terabit capacities or microsecond latencies expected to be necessary for aggregated 6G x-Haul transport [11]. Although 25G-PON represents a significant advancement and may be applicable in certain 5G/5.5G scenarios, a much deeper technological evolution will be required for 6G transport [16].

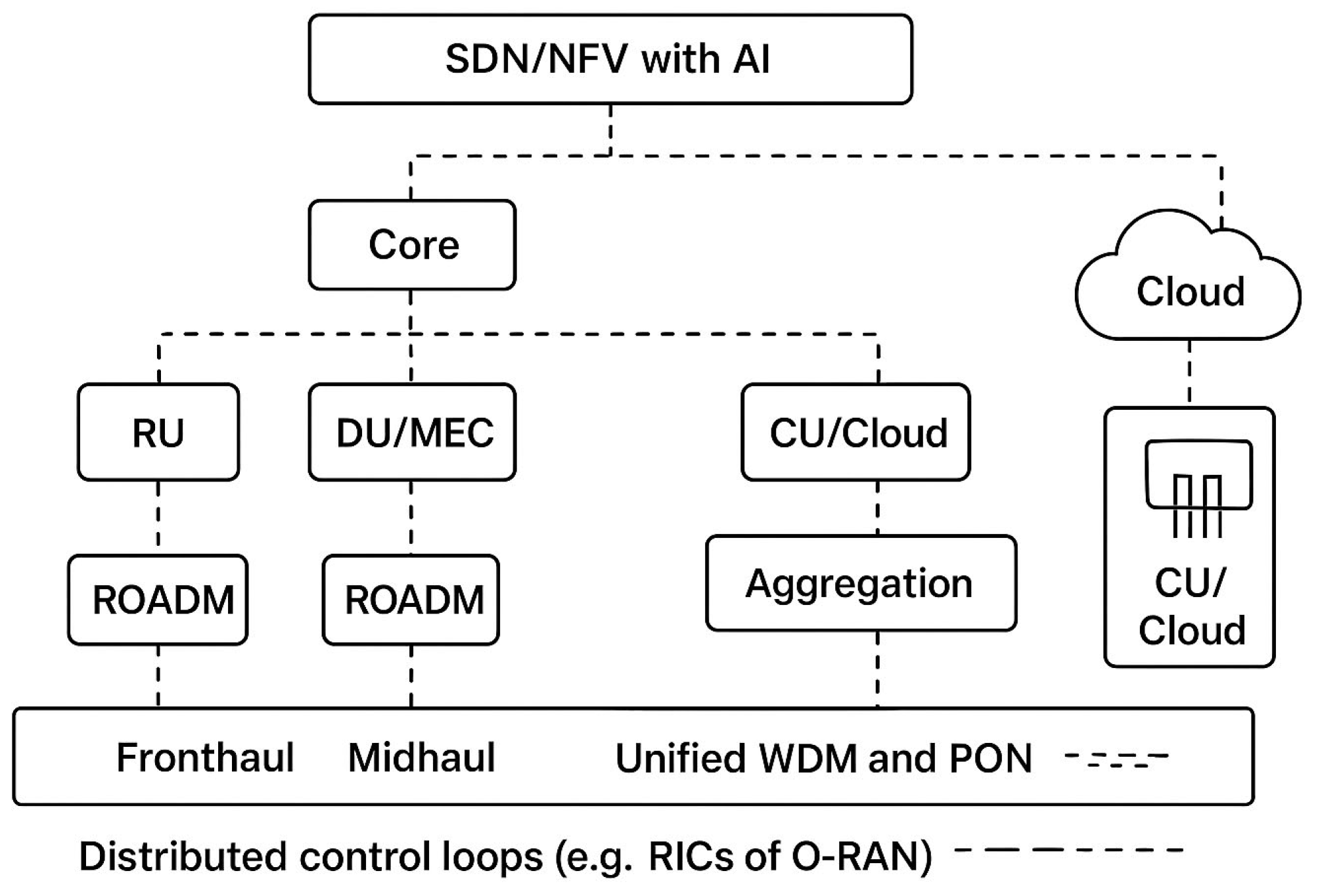

2.1.2. Arquitectura x-Haul Convergente y Flexible Para 6G

- x-Haul Convergence: A unified transport architecture is essential to transparently and efficiently integrate the fronthaul (RU–DU), midhaul (DU–CU), and backhaul (CU–Core/Cloud) segments [1]. This convergence should support the transport of diverse traffic types (user data, control, synchronisation, management, and AI-related data) with different QoS requirements over a shared physical infrastructure, thereby optimising resource utilisation. The architecture must be adaptable to multiple deployment scenarios, including Distributed Radio Access Networks (DRAN), Centralised (CRAN), and Virtualised (VRAN) topologies [17].

- Functional Flexibility (Splits): The disaggregation of base station functions (Baseband Unit—BBU) into Distributed Units (DU) and Centralised Units (CU), promoted by initiatives such as O-RAN, enables flexible division of radio protocol functions (functional splits) [1]. The 6G optical transport network must dynamically support multiple split options (FFS—Flexible Functional Splits) [10]. This allows optimisation of the trade-off between required fronthaul bandwidth, end-to-end latency, and the degree of baseband centralisation, adapting to the specific needs of each service and deployment scenario.

- AI-Native Integration: Unlike 5G, where AI is often introduced as an overlay layer, the 6G architecture must be conceived from the ground up to integrate AI natively (AI-Native) [10]. This means that data collection, AI processing, and ML model execution capabilities must be embedded within optical network elements and management systems, enabling intelligent optimisation, advanced automation, and the creation of AI-driven services.

- Openness and Interoperability: The adoption of open interfaces, such as those specified by the O-RAN Alliance, and the promotion of open-source approaches are crucial to eliminating vendor lock-in, fostering innovation, reducing costs, and ensuring interoperability within a multi-vendor ecosystem [3]. Global and coordinated standardisation across different organisations (ITU, IEEE, 3GPP, ETSI, O-RAN) is indispensable for the successful deployment of 6G [17].

- Proposed Optical Architecture: The emerging architectural vision for 6G x-Haul is based on highly flexible and reconfigurable Wavelength Division Multiplexing (WDM) optical networks. Elements such as Reconfigurable Optical Add-Drop Multiplexers (ROADMs) are extended beyond the core and metro layers to reach the network edge, enabling dynamic wavelength switching [18]. These reconfigurable WDM networks could be combined with advanced PON technologies (such as Coherent PON) for access and initial aggregation, and could potentially integrate other technologies such as Free-Space Optics (FSO) in specific scenarios. Mesh and flattened architectures are favoured to increase resilience and provide multiple routing paths, as opposed to more rigid ring topologies [19].

2.1.3. Integration with Edge Computing and Distributed Architectures

- Cloud–Edge–Device Continuum: 6G materialises the concept of a computational continuum that extends from centralised data centres (Cloud), through multiple tiers of computing nodes at the network edge (Edge Computing, Fog Computing), to processing capabilities embedded in end-user devices themselves [19]. The optical network acts as the connective fabric that unites this continuum.

- MEC (Multi-Access Edge Computing) and Edge AI: Edge computing (MEC) is crucial for processing data and executing latency-sensitive applications—such as industrial control, AR/VR, and autonomous driving—as well as for enabling AI functions (Edge AI) close to the end user [19]. The optical transport network must provide ultra-low-latency, high-bandwidth connectivity to these MEC nodes, whose locations may range from cell sites to regional central offices [11]. The evolution of ETSI MEC is aimed at supporting 6G requirements [20].

- Distributed Computing Paradigms: Beyond MEC, the 6G architecture must support paradigms such as Fog Computing, which introduces an intermediate computing layer between the edge and the cloud, as well as other distributed approaches that optimise processing placement according to application requirements [18].

- Joint Communication–Computation Optimisation (JCC): The efficiency of distributed applications in 6G will depend on the network’s ability to jointly manage and optimise communication resources (optical bandwidth, latency) and computing resources (CPU, GPU, memory, storage) across the Cloud–Edge continuum [13]. The optical network must enable this joint management by providing not only connectivity but also link-state awareness and rapid reconfiguration capabilities to support the optimal placement of computational tasks.

2.1.4. Second- and Third-Order Perspectives: Architectural Implications

2.1.5. Extreme 6G Requirements for Optical Transport

- Throughput: Peak per-device rates are expected to reach or exceed 1 Tbps, with sustained user-experienced rates in the hundreds of Gbps. Specific applications—such as high-fidelity holographic communications—may require capacities surpassing 4 Tbps per stream.

- Deterministic Latency: End-to-end (E2E) latency must be drastically reduced, moving from the millisecond-level characteristic of 5G URLLC to microsecond (µs) levels, with targets in the 10–100 µs range. Moreover, a strict requirement is that latency be deterministic, with minimal variation (jitter). Jitter stress is a limiting factor for packet transport, as the optical network must guarantee predictable and stable latency—fundamental for real-time control systems and HRLLC (Hyper-Reliable Low-Latency Communication) applications.

- Nanosecond-Level Synchronisation: The precise coordination of complex network operations—such as advanced beamforming, distributed computing, and Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC)—demands time synchronisation accuracy at the nanosecond (ns) level across the optical network. This precision requirement represents a 1000-fold improvement over 5G.

3. Enabling Optical Technologies for 6G

- X-Haul Convergence: A unified transport architecture is essential to seamlessly integrate fronthaul, midhaul, and backhaul over a reconfigurable WDM infrastructure.

- Functional Flexibility (FFS): The disaggregation of base station functions (promoted by O-RAN) into Distributed Units (DUs) and Centralised Units (CUs) enables dynamic division of radio functions. The 6G optical transport must be capable of dynamically supporting these split options to optimise the trade-off between required bandwidth, end-to-end latency, and the degree of processing centralisation.

3.1. Evolution of PON: Beyond 50G

3.1.1. 50G-PON

3.1.2. 100G/200G-PON and Beyond

3.1.3. Coherent Optical Access (CPON—Coherent PON)

- Higher Receiver Sensitivity: Enables greater optical path losses, translating into longer reach or a higher number of users per OLT port (split ratio).

- Advanced Modulation Formats: Allows the use of spectrally efficient modulation schemes (e.g., QAM), increasing the capacity per wavelength.

- DSP-Based Dispersion Compensation: The DSP inherent to coherent detection can linearly compensate for chromatic dispersion and other optical channel impairments.

- Channel Selectivity: Facilitates WDM-PON implementation by allowing fine receiver tuning.

3.1.4. WDM-PON

3.2. Exponential Capacity Increase: SDM and New Bands

Spatial Division Multiplexing (SDM)

- Multi-Core Fibre (MCF): Integrates multiple cores (light-guiding paths) within a single fibre cladding. Each core behaves as an independent fibre, multiplying total capacity by the number of cores [12]. The main technical challenge lies in inter-core crosstalk, where light leaks from one core into adjacent ones, causing interference. Minimising this crosstalk requires highly precise fibre designs and manufacturing techniques [12].

- Few-Mode Fibre (FMF): Employs a single (or enlarged) core that supports the propagation of multiple spatial modes of light, each carrying an independent data signal [12]. It requires modal multiplexing/demultiplexing techniques (optical MIMO) and Digital Signal Processing (DSP) to separate signals at the receiver. In addition to specialised fibres, SDM demands compatible optical components such as spatial multiplexers/demultiplexers and optical amplifiers capable of simultaneously amplifying signals across all cores or modes [12]. The associated complexity and cost remain significant barriers to large-scale deployment at present.

- New Optical Bands (Beyond C + L): Traditional optical transmission has focused on the C-band (Conventional, ~1530–1565 nm) and L-band (Long, ~1565–1625 nm) due to the availability of Erbium-Doped Fibre Amplifiers (EDFA). To further increase per-fibre capacity, active research is investigating the utilisation of other ITU-T-defined transmission bands: O (Original, ~1260–1360 nm), E (Extended, ~1360–1460 nm), S (Short, ~1460–1530 nm), and U (Ultra-long, ~1625–1675 nm) [29]. Recent experiments have demonstrated the feasibility of ultra-long-haul transmission (>800 km) with aggregate capacities exceeding 100 Tbps by jointly exploiting the C, L, and U bands through innovative techniques such as parametric optical band conversion for U-band amplification [30]. Opening up these new bands could expand the total usable fibre bandwidth beyond 20 THz [30], but this requires the development of new optical components (amplifiers, filters, etc.) and efficient conversion techniques to operate within these spectral regions.

3.3. Drastic Latency Reduction: Hollow-Core Fibre (HCF)

3.3.1. Operating Principle

3.3.2. Additional Benefits

3.3.3. Status and Advances

3.3.4. Deployment Challenges

3.4. Flexible and Resilient Connectivity: Free-Space Optics (FSO)

3.4.1. Concept and Application in 6G x-Haul

3.4.2. Advantages

3.4.3. Technical Challenges

3.4.4. Solutions

3.5. Advanced Optical Components: Photonics and Switching

3.5.1. Silicon Photonics and PICs (Photonic Integrated Circuits)

- Miniaturisation: A drastic reduction in the size and weight of optical components.

- Lower Energy Consumption: Integration reduces losses and the power required for inter-component connections.

- Mass Production and Cost: Leverages the economies of scale of the semiconductor industry.

- Co-Packaged Optics (CPO): Facilitates close integration of optical and electronic components to reduce latency and power consumption at the electro–optical interface.

- Silicon photonics and PICs are therefore crucial for developing compact, low-power, and cost-effective optical transceivers, essential for dense 6G edge deployments and for meeting the increasing bandwidth demand of AI-driven data centres [35].

3.5.2. Optical Switching and ROADMs

3.6. Second- and Third-Order Perspectives: Technological Synergies and Trade-Offs

4. Intelligent Management and Orchestration of the 6G Optical Network

4.1. The Role of SDN/NFV: Towards Automation and Programmability

4.1.1. SDN (Software-Defined Networking)

4.1.2. NFV (Network Functions Virtualization)

4.1.3. Integration SDN/NFV

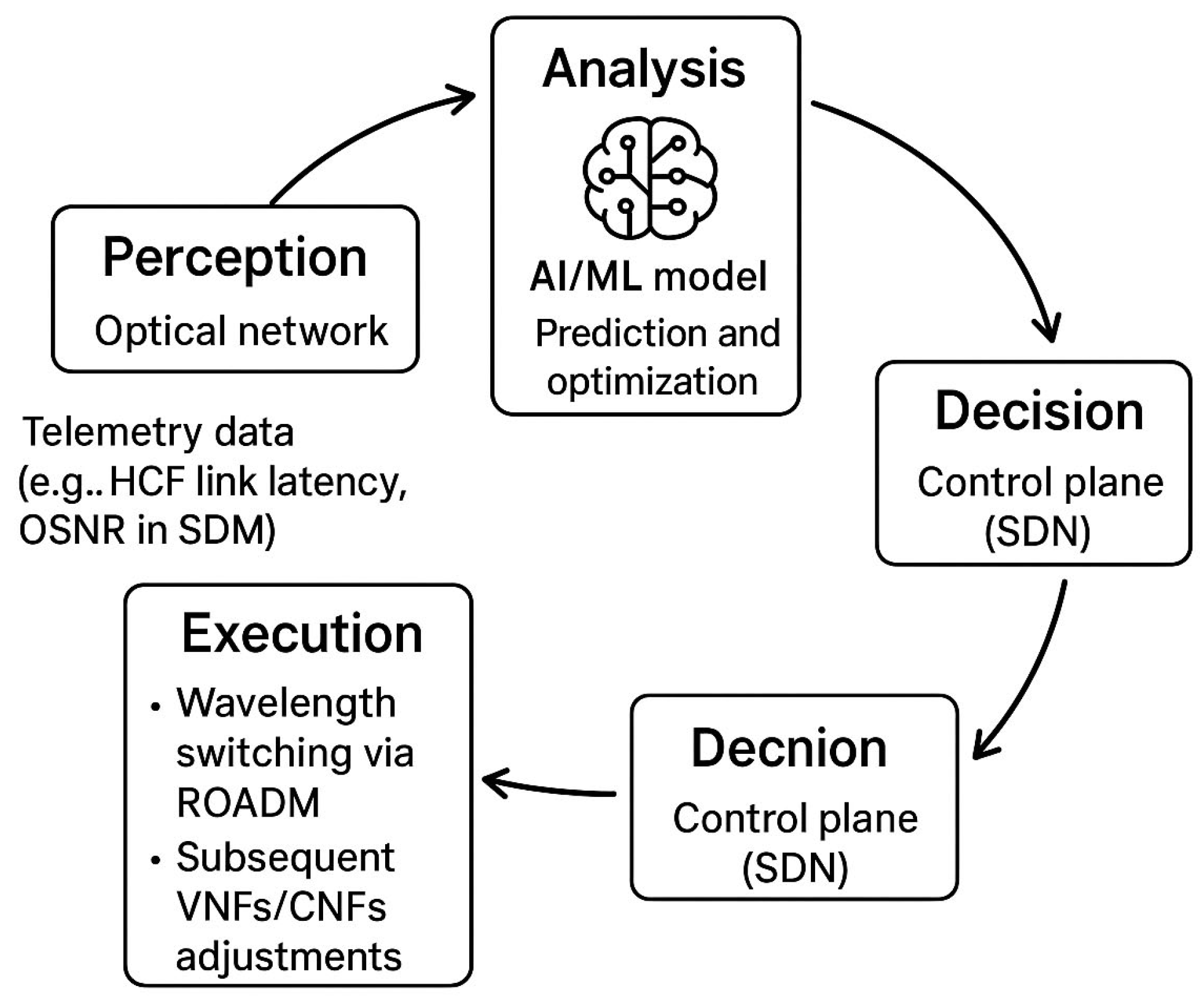

4.2. AI/ML Applications in Optical Network Management

4.2.1. Intelligent Orchestration and Management:

4.2.2. Resource Optimisation

4.2.3. Predictive Maintenance

4.2.4. Autonomous Management (Zero-Touch Management—ZSM)

4.2.5. Security

4.3. Second- and Third-Order Perspectives: AI as Master Orchestrator and Critical Challenge

- Scarcity of High-Fidelity Data and Dependence on Digital Twins: For AI models to be accurate, they require massive amounts of high-quality telemetry data obtained from the optical network. However, acquiring such data from operational optical networks in real time—especially for rare faults or anomalous phenomena—is difficult. Digital Twins are therefore essential. These virtual models allow the simulation of extreme scenarios (e.g., failures in HCF or SDM) and the generation of the massive and realistic datasets needed to train and test AI/ML algorithms, minimising the risk of errors during real-world deployment.

- Interpretability and Trustworthiness: Autonomous systems must be trustworthy. The lack of transparency in AI model decisions (the “black-box” problem) poses a significant operational risk. An erroneous or poorly trained optimisation decision could propagate rapidly across an autonomous, ultra-fast optical network, causing cascading systemic failures. The development of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques is therefore required to enable operators to audit and trust autonomous management actions.

- Risks of Incorrect Autonomous Configuration: Automation eliminates human error but introduces the possibility of algorithmic errors. Since a failure in the optical network may impact an enormous volume of services (up to 100 Tbit/s), the network must be designed for self-healing. This means that AI must be capable of detecting even the slightest irregularities (early signs of fault) and triggering automatic corrective actions (such as rerouting communications to new paths) with extremely low latency, preventing systemic failures without manual intervention.

5. Precision Synchronisation in 6G Optical Networks

5.1. Strict Synchronisation Requirements

5.1.1. Coordinated Multi-Point Transmission/Reception (CoMP)

5.1.2. Coordinated Massive MIMO and High-Precision Beamforming

5.1.3. Advanced Carrier Aggregation (CA)

5.1.4. URLLC/HRLLC Applications

5.1.5. Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC)

5.2. Protocols and Techniques: PTP over Fibre

5.2.1. PTP (IEEE 1588)

5.2.2. Hierarchical Architecture

5.2.3. Key Mechanisms

- Precise Timestamping: Accurate time-stamping of PTP messages (Sync, Delay_Req, etc.) at the exact moment of transmission and reception at network interfaces. Hardware-based timestamping is preferred to achieve maximum precision [8].

- Best Master Clock Algorithm (BMCA): A distributed algorithm that automatically selects the best available clock as the master within each network segment, establishing the synchronisation hierarchy and preventing loops [50].

- Delay Measurement: Mechanisms to measure and compensate for the propagation delay of PTP messages across the network, using either End-to-End or Peer-to-Peer methods [50].

5.2.4. ITU-T Profiles for Telecommunications

5.2.5. Implementation over Optical Fibre

5.3. Second- and Third-Order Perspectives: Synchronisation as a Critical Service

6. Implementation and Standardisation Challenges

6.1. Cost and Complexity Analysis

6.1.1. Infrastructure Investment

- New Fibres: Potential deployment of advanced fibres such as HCF or MCF/FMF in critical network segments, although their manufacturing and deployment costs remain high [40].

- Equipment Upgrades: Replacement or modernisation of optical transceivers (towards high-speed coherent types), ROADMs (more flexible and faster, deployed closer to the edge), and Ethernet switches (with TSN and high-precision PTP support) [50].

- Network Densification: Increasing the number of cell sites and optical access points to improve coverage and capacity, particularly when operating at higher frequencies [40].

- Technological and Operational Complexity: The integration of multiple novel technologies (CPON, SDM, HCF, FSO, PICs, AI/ML, SDN/NFV) into a cohesive network significantly increases design, implementation, management, and maintenance complexity [40]. Highly skilled personnel are required to operate and optimise such advanced networks [40]. Managing heterogeneous and distributed networks, with virtualised functions and software-defined control, introduces new operational challenges.

- Cost Mitigation Strategies: To make the transition viable, various strategies are being explored:

- Reusing 5G Infrastructure: Maximising the use of existing fibre and cell site infrastructure [40].

- Adopting Open RAN: Encouraging vendor competition and the use of COTS (Commercial Off-The-Shelf) hardware to reduce equipment costs [40].

- Infrastructure Sharing: Collaborative models where multiple operators share passive (fibre, towers) or even active network elements to reduce CapEx and OpEx [40].

- Virtualisation and Automation: NFV and SDN, combined with AI-driven automation, can reduce long-term operational costs by optimising resource usage and simplifying management [40].

6.1.2. Energy Consumption and Sustainability

- Quantitative Optical Savings: The adoption of fully optical networks (minimising O-E-O conversions) is the most effective strategy to mitigate the rise in energy consumption. Analyses show that optical networks can reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by up to 88% per gigabit compared with legacy networks. Technologies such as low-power PICs and the use of optical bypass through ROADMs are fundamental for minimising energy consumption at the physical layer.

- Intelligent Management: The use of AI/ML and SDN to dynamically optimise configuration and energy consumption (e.g., sleep modes in transceivers during low-traffic periods) is essential for efficient and sustainable energy management.

- Energy Challenge: Although 6G aspires to achieve significantly higher energy efficiency per bit transmitted (a key KPI), the expected exponential growth in data traffic, massive proliferation of connected devices, and the energy required for new functionalities (edge computing, AI model training and inference) could lead to a net increase in total network energy consumption [9]. This poses both economic (operational cost) and environmental (carbon footprint) challenges. Equipment lifecycle issues—including manufacturing and electronic waste (e-waste)—also raise sustainability concerns [9].

- Solutions for Energy-Efficient Optical Networks: Research and implementation efforts are underway to develop a wide range of approaches aimed at improving the energy efficiency of the 6G optical infrastructure.

- Low-Power Components: Development and adoption of inherently more efficient optical components, such as silicon photonics-based PICs, integrating multiple functions on a single chip to reduce losses and power use [35].

- Energy-Efficient Optical Transceivers: Design of high-speed (Tbps) transceivers that minimise energy consumption per transmitted bit [19].

- Optimised Optical Architectures: Network architectures designed to minimise unnecessary O–E–O conversions, favouring direct optical switching (optical bypass) and eliminating intermediate layers (e.g., IP-over-optical flattening) to reduce overall energy consumption [19].

- Low-Power Modes: Implementation of sleep or low-power modes for network components (transceivers, amplifiers, switches) during low-traffic periods [51].

- Intelligent Energy Management: Use of AI/ML and SDN to monitor energy consumption in real time and dynamically optimise network configurations (e.g., selectively powering down elements, routing traffic through efficient paths) to minimise energy expenditure without compromising QoS [9].

- Renewable Energy Sources: Powering network nodes and data centres with renewable energy [9].

6.1.3. Security, Resilience, and Interoperability in Open Architectures

- Zero Trust and Resilience: To ensure the availability of essential services and protect network integrity, it is indispensable to migrate to a Zero Trust security model. This model requires continuous verification of the identity and health of every user, device, and optical or virtualised service, mitigating the risks introduced by a complex supply chain.

- Interoperability as a Pillar of Resilience: Global standardisation is not only crucial for economic viability and economies of scale, but also a pillar of systemic resilience. A coherent set of global standards ensures interoperability among equipment from different vendors, enabling rapid component replacement and preventing systemic failures caused by reliance on a single supplier—an essential requirement for achieving 7- to 9-nines network reliability. Effective collaboration and alignment among standardisation bodies (ITU-T, IEEE, 3GPP, O-RAN) are therefore critical.

- Critical Need: To create a vibrant global market, foster competition, reduce costs through economies of scale, and ensure a seamless user experience (including international roaming), it is essential that equipment and solutions from different vendors interoperate smoothly. Global harmonised standardisation of interfaces, protocols, and architectures is the key to achieving such interoperability [34].

- Key Standardisation Bodies (SDOs): Several international organisations play fundamental and often complementary roles in defining 6G standards, including those relevant to optical transport:

- ITU-R (International Telecommunication Union—Radiocommunication Sector): Leads the global vision for IMT-2030 (6G), defining use scenarios, performance requirements, and evaluation criteria for radio interface technologies [34].

- ITU-T (Telecommunication Standardisation Sector): Focuses on the standardisation of fixed networks, including optical transport (OTN), access networks (PON—Study Group 15, SG15), Ethernet, synchronisation (G.827x), and network management and control (e.g., YANG models) [11].

- IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers): Develops fundamental standards for networking technologies such as Ethernet (IEEE 802.3), local wireless networks (Wi-Fi, IEEE 802.11), Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN, within IEEE 802.1), and PTP (IEEE 1588). It also defines high-speed optical interfaces (e.g., 800G, 1.6T) [44].

- 3GPP (3rd Generation Partnership Project): The main body responsible for the standardisation of mobile cellular systems (RAN and Core Network). Defines architectures, interfaces (including eCPRI for fronthaul), protocols, and functionalities, including AI/ML integration (e.g., NWDAF). Releases 20 and 21 will mark the beginning of specific normative work for 6G [13].

- O-RAN Alliance: Focuses on defining open and disaggregated RAN interfaces to promote multi-vendor interoperability and AI-driven intelligence through RAN Intelligent Controllers (RICs) [52].

- ETSI (European Telecommunications Standards Institute): Plays a key role in transposing 3GPP standards into European norms and works in complementary areas such as MEC, NFV, ZSM (Zero-Touch Service Management), and SDN controllers such as TeraFlowSDN [42].

- Other Forums and Alliances: Organisations such as OIF (Optical Internetworking Forum), CableLabs, and MOPA (Mobile Optical Pluggable Alliance) also contribute to the standardisation of specific optical interfaces and components [17].

- Inter-Organisational Coordination: Given the convergence of fixed and mobile, wired and wireless, and communication and computing technologies in 6G, effective collaboration and alignment among these various standardisation bodies are more crucial than ever to avoid fragmentation and to ensure a coherent and globally harmonised standards framework [53].

6.1.4. Second- and Third-Order Perspectives: The 6G Ecosystem

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

7.1. Summary of Key Findings

7.2. Strategic Recommendations

7.2.1. Prioritise Investment in Technology Maturation and Cost Reduction:

- HCF and PICs: R&D efforts should focus on reducing the manufacturing costs of HCF for deployment in latency-critical links, and on the standardisation of high-performance, low-power PICs/CPO.

- Optical Spectrum: Investment is essential in the development of amplifiers and components compatible with the new optical bands (O, E, S, and U) to unlock the full capacity of fibre.

7.2.2. Coordinated Standardisation Roadmap:

- ITU-T SG15: Accelerate the standardisation of advanced fibre management protocols (SDM, HCF) and, crucially, ultra-high-speed CPON standards to ensure interoperability of access hardware.

- O-RAN Alliance/3GPP: Harmonise high-precision PTP profiles (G.827x) to guarantee nanosecond-level synchronisation across flexible fronthaul architectures (FFS).

7.2.3. Adoption of Trust Architectures and Digital Twins:

- Implement the Zero Trust security model across the entire transport and management chain to ensure network integrity in complex multi-vendor environments.

- Mandate the use of Digital Twin platforms for the design, simulation, and rigorous validation of AI-assisted network configurations before live deployment, minimising the risk of autonomous failures.

7.2.4. Focus on TCO and Sustainability:

- Ensure that Energy Efficiency KVIs become mandatory selection criteria for new optical hardware.

- Promote regulatory policies that incentivise active infrastructure sharing (fibre, ducts, COTS) and AI-driven automation as key strategies for reducing CapEx, OpEx, and environmental impact.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fayad, A.; Cinkler, T.; Rak, J. Toward 6G Optical Fronthaul: A Survey on Enabling Technologies and Research Perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 27, 629–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkos, I.; Christofidis, C.; Uzunidis, D.; Moschopoulos, K.; Papapavlou, C.; Tranoris, C.; Marom, D.M.; Nazarathy, M.; Munoz, R.; Famelis, P.; et al. The “X-Factor” of 6G Networks: Optical Transport Empowering 6G Innovations. IT Prof. 2024, 26, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Uzzal, M.S. Beyond 5G: A Comprehensive Exploration of 6G Wireless Communication Technologies. 2024; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataria, H.; Shafi, M.; Molisch, A.F.; Dohler, M.; Sjoland, H.; Tufvesson, F. 6G Wireless Systems: Vision, Requirements, Challenges, Insights, and Opportunities. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 1166–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solyman, A.A.A.; Yahya, K. Key Performance Requirement of Future next Wireless Networks (6G). Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2021, 10, 3249–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE SA. How Time-Sensitive Networking Benefits Fronthaul Transport. Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/beyond-standards/how-time-sensitive-networking-benefits-fronthaul-transport/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Nadim, M.; Islam, T.U.; Reddy, S.; Zhang, T.; Meng, Z.; Afzal, R.; Babu, S.; Ahmad, A.; Qiao, D.; Arora, A.; et al. AraSync: Precision Time Synchronization in Rural Wireless Living Lab. In Proceedings of the ACM MobiCom 2024—Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, Washington, DC, USA, 18–22 November 2024; pp. 1898–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Rahmani, M.; Chetty, S.B.; Tsiropoulou, E.E.; Arslan, H.; Debbah, M.; Quek, T. Towards Sustainability in 6G and beyond: Challenges and Opportunities of Open RAN. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.08353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson. 6G Network Architecture—A Proposal for Early Alignment. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/ericsson-technology-review/articles/6g-network-architecture (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ishtiaq, M.; Saeed, N.; Khan, M.A. Edge Computing in the Internet of Things: A 6G Perspective. IT Prof. 2024, 26, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, G.; Luís, R.S.; Puttnam, B.J. Space-Division Multiplexing for Optical Fiber Communications. Optica 2021, 8, 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennanen, H.; Hänninen, T.; Tervo, O.; Tölli, A.; Latva-aho, M. 6G: The Intelligent Network of Everything—A Comprehensive Vision, Survey, and Tutorial. IEEE Access 2024, 13, 1319–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaez-Ghaemi, R.; Solutions, V. The Evolution of Fronthaul Networks. 2020. Available online: https://www.viavisolutions.com/en-us/literature/evolution-fronthaul-networks-white-papers-books-en.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Skogman, V. Building Efficient Fronthaul Networks Using Packet Technologies; Ericsson: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sizer, T.; Samardzija, D.; Viswanathan, H.; Le, S.T.; Bidkar, S.; Dom, P.; Harstead, E.; Pfeiffer, T. Integrated Solutions for Deployment of 6G Mobile Networks. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOPA Alliance. MOPA Technical Paper v3.2. 2025. Available online: https://mopa-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MOPA_Technical_Paper-v3.2-Final.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Li, P.; Fan, J.; Wu, J. Exploring the Key Technologies and Applications of 6G Wireless Communication Network. iScience 2025, 28, 112281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkos, I.; Uzunidis, D.; Christofidis, C.; Moschopoulos, K.; Papapavlou, C.; Trantzas, K.; Marom, D.M.; Munoz, R. Challenges and Innovations of Transport Networks to Support 6G Use-Cases. In Proceedings of the 2024 24th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Bari, Italy, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; You, X.; Wei, N.; Nan, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, X.; Ai, M.; Tao, X.; Feng, Z.; et al. Overview of AI and Communication for 6G Network: Fundamentals, Challenges, and Future Research Opportunities. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2024, 68, 171301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J. El Futuro de Las Redes: Explicación de Ethernet de 400 GbE—Fibermall.Com 2024. Available online: https://www.fibermall.com/es/blog/400gbe-ethernet.htm?srsltid=AfmBOoq2OBEAAjPkDPA1JUBy35YfSFCTtIzUfPX8EHIJ76wkYcUsUFFS (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Sanjalawe, Y.; Fraihat, S.; Al-E’mari, S.; Abualhaj, M.; Makhadmeh, S.; Alzubi, E. A Review of 6G and AI Convergence: Enhancing Communication Networks with Artificial Intelligence. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2025, 6, 2308–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Niyato, D.; Huang, K. Integrated Sensing and Edge AI: Realizing Intelligent Perception in 6G. 2025. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2501.06726 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Tshakwanda, P.M.; Arzo, S.T.; Devetsikiotis, M. Advancing 6G Network Performance: AI/ML Framework for Proactive Management and Dynamic Optimal Routing. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 5, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calix. 50G Passive Optical Networks: What Is It All About? 2025. Available online: https://www.calix.com/blog/2025/04/passive-optical-networks.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Zhang, D.; Liu, D.; Wu, X.; Nesset, D. Progress of ITU-T Higher Speed Passive Optical Network (50G-PON) Standardization. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2020, 12, D99–D108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jia, Z.; Choutagunta, K.; Campos, L.A. Coherent Passive Optical Network: Applications, Technologies, and Specification Development [Invited Tutorial]. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2025, 17, A71–A86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanclou, P.; Suzuki, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Boldi, M.R.; Tanaka, K.; Hong, S.; Rodrigues, C.; Neto, L.A.; Ming, J. How Does Passive Optical Network Tackle Radio Access Network Evolution? J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2017, 9, 1030–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 5G Americas. The 6G Upgrade in the 7–8 GHz Spectrum Range. 2024. Available online: https://www.5gamericas.org/the-6g-upgrade-in-the-7-8-ghz-spectrum-range/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- NTT. World’s First Long-Haul Optical Inline-Amplified Transmission over 100 Tbit/s Capacity Using Ultra Long-Wavelength Band Conversion Toward IOWN/6G, Single-Core Optical Fiber Capacity More than Three Times Larger than Current Technology. Available online: https://group.ntt/en/newsrelease/2024/09/03/240903b.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Inniss, D. Hollow Core Fiber Gives High Frequency Traders an Edge 2020. Available online: https://www.laserfocusworld.com/fiber-optics/article/14183435/hollow-core-fiber-gives-high-frequency-traders-an-edge (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Li, J.; Han, Y. Ultra-Low-Loss Anti-Resonant Hollow-Core Fiber with Nested Concentric Circle Structures. Results Phys. 2022, 43, 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topfiberbox. Air-Core Optical Fiber: 6G Network Breakthrough Technology. 2025. Available online: https://topfiberbox.com/air-core-optical-fiber-6g/?srsltid=AfmBOop0_4wAQ9nE31gt-B8aTzcD7zPY9RZxz_MzlG5gbBxpJEgqQGM2 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Fayad, A.; Pelle, I.; Cinkler, T.; Sonkoly, B. Harnessing Free Space Optics for Efficient 6G Fronthaul Networks: Challenges and Opportunities. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H. Silicon Photonics and Photonic Integrated Circuits 2025–2035: Technologies, Market, Forecasts; IDTechEx: Cambridge, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Ranaweera, C.; Edirisinghe, S.; Lim, C.; Nirmalathas, A.; Wosinska, L.; Song, T. Reconfigurable Optical Crosshaul Architecture for 6G Radio Access Networks. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2023, 15, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovanna, P.; Puleri, M.; Bottari, G.; Cavaliere, F. Intent-Based AI System in Packet-Optical Networks towards 6G [Invited]. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2024, 16, C31–C42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunidis, D.; Moschopoulos, K.; Papapavlou, C.; Paximadis, K.; Marom, D.M.; Nazarathy, M.; Muñoz, R.; Tomkos, I. A Vision of 6th Generation of Fixed Networks (F6G): Challenges and Proposed Directions. Telecom 2023, 4, 758–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. The 6G Network Is on the Horizon; CableLabs: Louisville, KY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, A. Implementing Cost-Effective 6G Networks: Strategies and Considerations. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389008580_Implementing_Cost-Effective_6G_Networks_Strategies_and_Considerations?channel=doi&linkId=67b015d98311ce680c63a33e&showFulltext=true (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Ranaweera, C.; Lim, C.; Tao, Y.; Edirisinghe, S.; Song, T.; Wosinska, L.; Nirmalathas, A. Design and Deployment of Optical X-Haul for 5G, 6G, and beyond: Progress and Challenges [Invited]. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 2023, 15, D56–D66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolkas, D.; Artuñedo Guillen, D.; Gavras, A.; Tranoris, C.; Laki, S.; Skarmeta Gómez, A.; Barraca, J.P.; Makropoulos, G.; Vilalta, R. Network & Service Management Advancements—Key frameworks and Interfaces towards open, Intelligent and reliable 6G networks. Zenodo 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.S.; Hussain, Z.; Ikram, M.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Mukhopadhyay, S. On Challenges of Sixth-Generation (6G) Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Survey of Requirements, Applications, and Security Issues. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2025, 233, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.H.; Feng, C.; Han, S.; Wang, X.; Quek, T.Q.S. Toward 6G Native-AI Network: Foundation Model Based Cloud-Edge-End Collaboration Framework. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2025, 63, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daws, R. IMT-2030 Vision: Industry Experts Outline the Path to 6G 2024. Available online: https://www.telecomstechnews.com/news/imt-2030-vision-industry-experts-outline-path-to-6g/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Unlocking the Full Potential of AI-Native 6G through Standards|Nokia.Com 2025. Available online: https://www.nokia.com/6g/unlocking-the-full-potential-of-ai-native-6g-through-standards/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. Data-Plane Design for AI-Native 6G Networks. 2024. Available online: https://www.huawei.com/en/huaweitech/future-technologies/data-plane-design-ai-native-6g-networks (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Letaief, K.B.; Shi, Y.; Lu, J.; Lu, J. Edge Artificial Intelligence for 6G: Vision, Enabling Technologies, and Applications. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2022, 40, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Wan, Y.; Baracca, P.; Wang, A. 6G Hyper Reliable and Low-Latency Communication—Requirement Analysis and Proof of Concept. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Hong Kong, China, 10–13 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girela-López, F.; López-Jiménez, J.; Jiménez-López, M.; Rodríguez, R.; Ros, E.; Díaz, J. IEEE 1588 High Accuracy Default Profile: Applications and Challenges. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45211–45220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOWN Global Forum. Open All-Photonic Network Functional Architecture October 2023. 2023. Available online: https://iowngf.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IOWN-GF-RD-Open_APN_Functional_Architecture-2.0.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Schmidt, R.; Katsalis, K.; Chang, C.Y.; Bauschert, T.; Nikaein, N. Time-Sensitive Networking for 5G Fronthaul Networks. In Proceedings of the ICC 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Dublin, Ireland, 7–11 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE 802 LAN/MAN Standards Committee. July 2024 Plenary Session—Montreal, QC, Canada. 2024. Available online: https://1.ieee802.org/july-2024-plenary-session-in-montreal-qc-canada/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

| KPI (Key Performance Indicator) | Unit | Typical 5G Value | Target 6G Value | Improvement Factor (Approx.) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Data Rate per Device | Gbps/Tbps | 20 Gbps | >1 Tbps | >50× | [11] |

| User-Experienced Data Rate | Mbps/Gbps | 100 Mbps | >1 Gbps | >10× | - |

| End-to-End (E2E) Latency (User Plane) | ms/µs | ~1 ms | 10–100 µs | 10×–100× | [11] |

| Reliability (URLLC/HRLLC) | % | 99.999% (five nines) | 99.9999–99.9999999% (seven–nine nines) | >100× (in error rate) | - |

| Connection Density | devices/km2 | 106 | 107–108 | 10×–100× | [11] |

| Synchronisation Accuracy | µs/ns | ~µs | ~ns | 1000× | [12] |

| Energy Efficiency (Network) | bits/Joule | ~107 | ~109 | ~100× | [11] |

| Parameter | Typical 5G Technology | Typical 5G Limitation | Target 6G Requirement | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fronthaul Capacity (per cell) | eCPRI over Ethernet/PON | Tens of Gbps | >500 Gbps | [14] |

| Aggregated Capacity (per site) | Aggregated Ethernet/PON | Hundreds of Gbps | >1–10 Tbps | [16] |

| Fronthaul Latency (E2E) | Standard Ethernet/TDM-PON | >100 µs (variable) | <100 µs (deterministic) | [14] |

| Fronthaul Jitter (PDV) | Standard Ethernet | Variable/High | Very Low/Controlled | [14] |

| Synchronisation Accuracy (Fronthaul) | PTP over Ethernet/PON | ~µs (variable) | ~ns (stable) | [14] |

| Technology | Key Principle | Main Benefit for 6G x-Haul | Main Challenge | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolved PON (>50G)/CPON | Higher speed per λ/Coherent Detection | High Access/Aggregation Capacity; Extended Reach/Split (CPON) | Cost/Complexity (CPON); Burst-Mode DSP (CPON) | [1] |

| SDM (MCF/FMF) | Spatial Multiplexing (Cores/Modes) | Per-Fibre Capacity Multiplication | Crosstalk (MCF); Complexity (Components, DSP); Cost | [4] |

| Hollow-Core Fibre (HCF) | Propagation in Air/Vacuum | Ultra-Low Latency (~30% reduction); Low Optical Nonlinearity | Manufacturing/Deployment Cost; Splice Losses; Robustness | [40] |

| Free-Space Optics (FSO) | Wireless Optical Transmission | Deployment Flexibility; High Bandwidth; Low Latency | Atmospheric Sensitivity; Alignment (PAT); Security | [1] |

| Silicon Photonics/PICs | On-Chip Optical Integration | Miniaturisation; Low Power Consumption; Cost (High Volume); Co-Packaging | Performance Limitations (vs. Other Materials); Coupling Losses | [35] |

| ROADMs/Optical Switching | Flexible Wavelength Switching | Network Agility; Reconfigurability; Efficiency (O–E–O Bypass) | Switching Speed vs. Latency; Edge Cost | [15] |

| Optical Technology | Primary KPI Addressed | Main 6G Application | Typical Use Scenario | Key Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCF (Hollow-Core Fibre) | Latency (<10 μs) | HRLLC (Industrial Control, Remote Surgery) | Critical fronthaul, High-frequency links (financial trading) | High deployment and splicing cost |

| SDM (MCF/FMF) | Capacity (Tbps) | High-Capacity Core Networks, Data Centre Interconnection (Cloud) | Massive backhaul | Component complexity, crosstalk risk |

| CPON (Coherent) | Capacity (Gbps)/Reach | Access and Aggregation, Midhaul with high split ratios | Dense metropolitan X-Haul | Transceiver cost, burst-mode DSP complexity |

| PICs/CPO | Energy Efficiency/Density | Edge Computing, Fronthaul Aggregation Nodes | Edge interconnects | Extreme performance vs. silicon scalability |

| FSO | Deployment Flexibility | Temporary Backhaul/Fronthaul, Hard-to-Reach Areas, NTN | Urban point-to-point links, Hybrid systems | Atmospheric vulnerability, need for precise PAT |

| Application Domain | Critical Management Task | Representative ML Algorithm/Model | Benefit in 6G |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Optimisation | Dynamic Route and Wavelength Assignment (RWA) | Reinforcement Learning (RL)/Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) | Real-time adaptation to traffic and channel variations, optimising throughput and latency. |

| Predictive Maintenance | Failure prediction in transceivers, fibre degradation | Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)/Anomaly Detection Algorithms | Reduction in operational costs and improved reliability (7–9 nines) by acting proactively before failure. |

| Autonomous Orchestration | Implementation of Intent-Based Management (IBM/IBN) | Large Language Models (LLMs)/Bayesian Belief Networks | Translation of high-level objectives into low-level optical and virtual network configurations. |

| Security and Resilience | Intrusion or attack detection (DDoS, tampering) | Unsupervised Learning (Clustering) | Identification of anomalous patterns in traffic or telemetry that indicate threats or systemic failures. |

| Design and Simulation | Modelling complex environments and AI training | Digital Twins/Generative AI | Simulation of ultra-dense environments (e.g., SDM, HCF) to validate and train robust, accurate AI models. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Astaiza Hoyos, E.; Bermúdez-Orozco, H.F.; Aldana-Gutierrez, J.A. Towards 6G: A Review of Optical Transport Challenges for Intelligent and Autonomous Communications. Computation 2025, 13, 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13120286

Astaiza Hoyos E, Bermúdez-Orozco HF, Aldana-Gutierrez JA. Towards 6G: A Review of Optical Transport Challenges for Intelligent and Autonomous Communications. Computation. 2025; 13(12):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13120286

Chicago/Turabian StyleAstaiza Hoyos, Evelio, Héctor Fabio Bermúdez-Orozco, and Jorge Alejandro Aldana-Gutierrez. 2025. "Towards 6G: A Review of Optical Transport Challenges for Intelligent and Autonomous Communications" Computation 13, no. 12: 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13120286

APA StyleAstaiza Hoyos, E., Bermúdez-Orozco, H. F., & Aldana-Gutierrez, J. A. (2025). Towards 6G: A Review of Optical Transport Challenges for Intelligent and Autonomous Communications. Computation, 13(12), 286. https://doi.org/10.3390/computation13120286