Information and Meaning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Model for Information

- the symbols that are used;

- the structure of IAs and the rules that apply to them—different ecosystems use different modelling tools to communicate within the ecosystem;

- the ways in which concepts are connected;

- the ways in which IAs are created and analysed;

- the channels that are used to interact.

“In the current view of how associative memory works, a great deal happens at once. An idea… activates many ideas, which in turn activate others. Furthermore, only a few of the activated ideas will register in consciousness; most of the work of associative thinking is silent, hidden from our conscious selves.”

3. Outcomes, Meaning, and Information Measures

4. Ecosystem Convention Limitations

- Ecosystem inertia: the lag in changes to ecosystem conventions when the environment changes;

- Connection strategy mismatch: limitations in how an IE searches and makes connections;

- Interpretation tangling: inadvertent mixing of interpretations from different ecosystems when chunks are used in more than one modelling tool (e.g., the use of language in mathematics);

- Tool limitations: limitations with respect to the characteristics of particular modelling tools;

- Physical mismatch: the ability to define references in modelling tools which cannot be interpreted with high quality because they violate the physical constraints that apply to the interpretation process or the slices which they refer to.

4.1. Ecosystem Inertia

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents…but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

“One of the most baffling and recalcitrant of the problems which business executives face is employee resistance to change.”

4.2. Connection Strategy Mismatch

“For information has trouble, as we all do, testifying on its own behalf... Piling up information from the same source doesn’t increase reliability. In general, people look beyond information to triangulate reliability.”

- a Logician or Mathematician may treat the content of an IA as a set of symbols with rules (content interpretation);

- a computer query may just search for the string “John Smith” (content interpretation);

- a person may also consider memories of John Smith as a person (event interpretation);

- more generally, people may relate content to events that they remember (for example, relating people to holidays, parties, or other social events)—this is a major focus of modern social media (event interpretation).

4.3. Interpretation Tangling

“[i]t is the use outside mathematics, and so the meaning [‘Bedeutung’] of the signs, that makes the sign-game into mathematics”

4.4. Tool Limitations

“The constituents of common sense […] like causation, force, time and substance […] worked well enough in the world in which our minds evolved, but they can leave our common sense ill-equipped to deal with some of the conceptual challenges of the modern world.”

“For a large class of cases of the employment of the word ‘meaning’—though not for all—this way can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language”

4.5. Physical Mismatch

4.6. Computer Simulation

4.7. Viewpoint Analysis

- analysis of the viewpoint (ecosystem, IE, and the purpose of the interpretation);

- the structure of the IA, its interpretation, and associated information measures;

- the applicability of the limitations applied above.

5. Logical Paradoxes

- because of the physical limitation, problem L does not lie in T or F and so the assertion is not meaningful;

- T intersects F and (as implied by the paradox) L lies in the intersection—in this case, the interpretation cannot discriminate “true” and “false”, so the chunk quality of “true” and “false” is low;

- T does not intersect F and L lies in one or the other—in this case, the assertion is implausible.

6. Floridi’s Questions about Information and Meaning

- P4: The data grounding problem: how can data acquire their meaning?

- P5: The problem of alethisation: how can meaningful data acquire their truth value?

- P7: Informational semantics: can information explain meaning?

- P16: The problem of localisation: can information be naturalised?

6.1. P4: The Data Grounding Problem

“How can the meanings of the meaningless symbol tokens, manipulated solely on the basis of their (arbitrary) shapes, be grounded in anything but meaningless symbols?”

6.2. P5: The Problem of Alethisation

6.3. P7: Informational Semantics and P16: The Problem of Localisation

“Can information be naturalised?…The problem here is whether there is information in the world independently of forms of life capable to extract it and, if so, what kind of information is in question”.

“Since P7 asks whether meaning can be at least partly be grounded in an objective, mind- and language-independent notion of information (naturalization of intensionality), it is strictly connected with P16…”

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IA | Information Artefact |

| IE | Interacting Entity |

| MfI | Model for Information |

References

- Walton, P. Measures of information. Information 2015, 6, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, P. A Model for Information. Information 2014, 5, 479–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnani, M.; Pääkkönen, K.; Annila, A. The physical character of information. Proc. R. Soc. A 2009, 465, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, P. Digital information and value. Information 2015, 6, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. The Philosophy of Information; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burgin, M. Theory of Information: Fundamentality, Diversity and Unification; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, R.K. What Is Information? Why Is It Relativistic and What Is Its Relationship to Materiality, Meaning and Organization. Information 2012, 3, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolander, T. Self-Reference, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Spring 2015 Edition. Edward, N.Z., Ed.; Available online: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2015/entries/self-reference/ (accessed on 29 June 2016).

- Avgeriou, P.; Uwe, Z. Architectural patterns revisited: A pattern language. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs (EuroPlop 2005), Bavaria, Germany, 6–10 July 2005.

- Harary, F. Graph Theory; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, M.; Michaelson, E. Reference, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2014 Edition. Edward, N.Z., Ed.; Available online: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/reference/ (accessed on 29 June 2016).

- Zins, C. Conceptual approaches for defining data, information, and knowledge. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Enlarged 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Planck, M. Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers; Frank, Gaynor, Translator; Williams & Northgate: London, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, P.R. How to Deal with Resistance to Change. Harvard Business Rev. 1954, 32, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Government Digital Inclusion Strategy. 2014. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-digital-inclusion-strategy/government-digital-inclusion-strategy (accessed on 29 June 2016).

- Brown, J.S.; Duguid, P. The Social Life of Information; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ryle, G.; Lewy, C.; Popper, K.R. Symposium: Why are the calculuses of logic and arithmetic applicable to reality? In Proceedings of the Logic and Reality, Symposia Read at the Joint Session of the Aristotelian Society and the Mind Association, Manchester, UK, 5–7 July 1946; pp. 20–60.

- Wittgenstein, L. Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, Revised Edition; Anscombe, G.E.M., Translator; von Wright, G.H., Rhees, R., Anscombe, G.E.M., Eds.; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein’s Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics; Diamond, C. (Ed.) Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1976.

- From Frege to Gödel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 3rd ed.; Van Heijenoort, J. (Ed.) Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1967; pp. 1879–1931.

- Pinker, S. The Stuff of Thought; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1953; Anscombe, G.E.M., Translator. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Syntactic Structures; Mouton: Paris, France; The Hague, The Netherlands, 1957; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.E. Cramming more components onto integrated circuits. Electronics 1965, 38, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnad, S. The Symbol Grounding Problem. Phys. D 1990, 42, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Chunk: coverage | Coverage captures the number of properties of slices that are incorporated in a chunk and how tightly the value constrains the property. |

| Chunk: resolution | Resolution measures the extent to which the interpretation can discriminate different slices. |

| Chunk: precision | Precision measures the degree to which different interpretations of the same content are the same. |

| Chunk: accuracy | Accuracy measures the proximity of an interpretation to the ecosystem interpretation. |

| Assertion: plausibility | Plausibility measures whether the actual relationship between the interpretation of chunks differs from that of the interpretation of the assertion as a whole. |

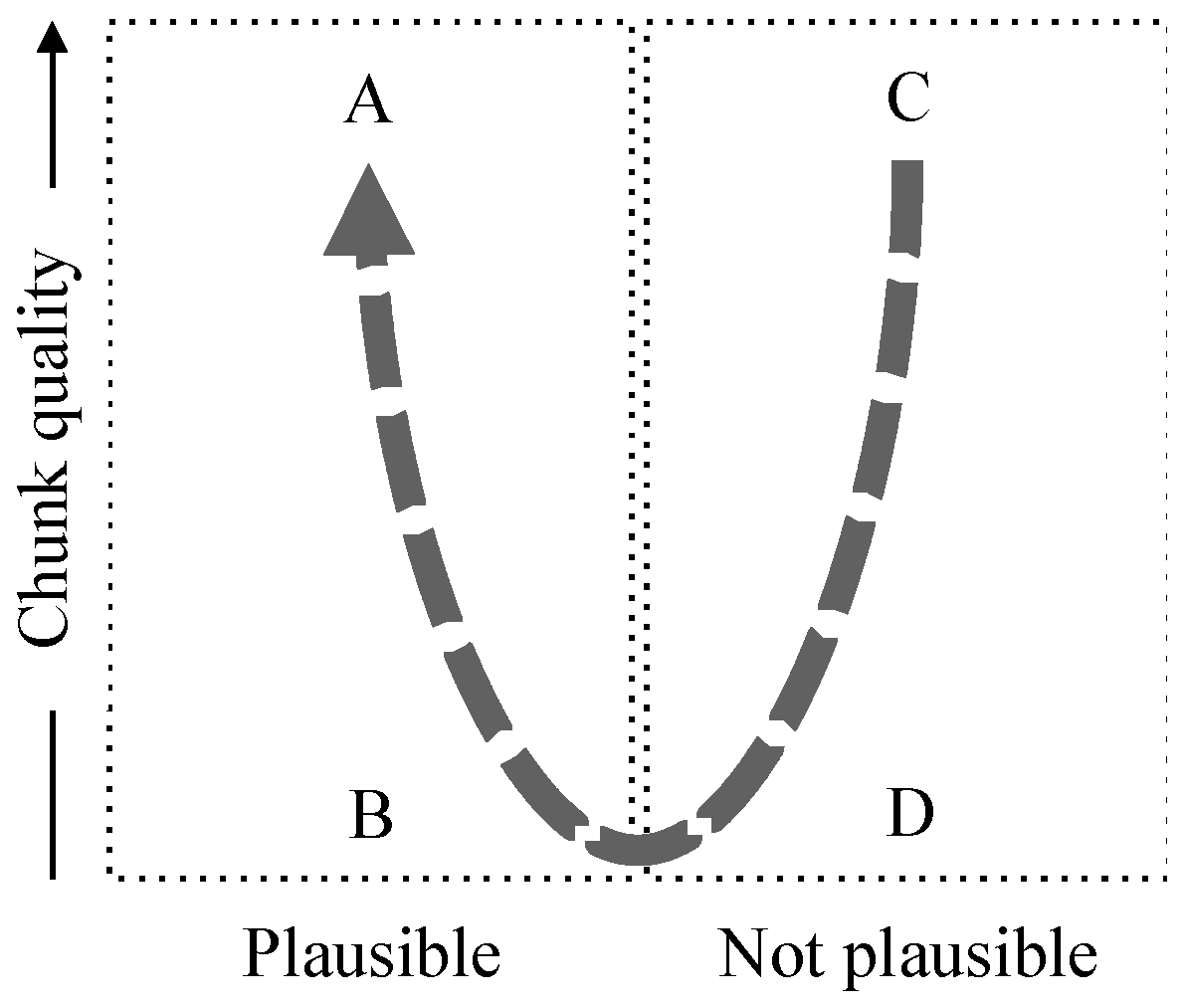

| Assertion: trustworthiness | Trustworthiness (called reliability of plausibility in [MoI]) is a combined measure of chunk quality and plausibility, where plausibility measures whether or not the interpretation of the corresponding chunks matches the set theoretic relationship implied by the assertion. See Figure 1. |

| Passage: trustworthiness | The trustworthiness of passages is derived from the trustworthiness of the assertions it contains and their consistency. |

| Friction | Friction measures the resources required for some process related to information (e.g., transmission, interpretation). |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walton, P. Information and Meaning. Information 2016, 7, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7030041

Walton P. Information and Meaning. Information. 2016; 7(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalton, Paul. 2016. "Information and Meaning" Information 7, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7030041

APA StyleWalton, P. (2016). Information and Meaning. Information, 7(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info7030041