Gamification in Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review of the Engagement–Efficacy–Ethics Trilemma

Abstract

1. Introduction

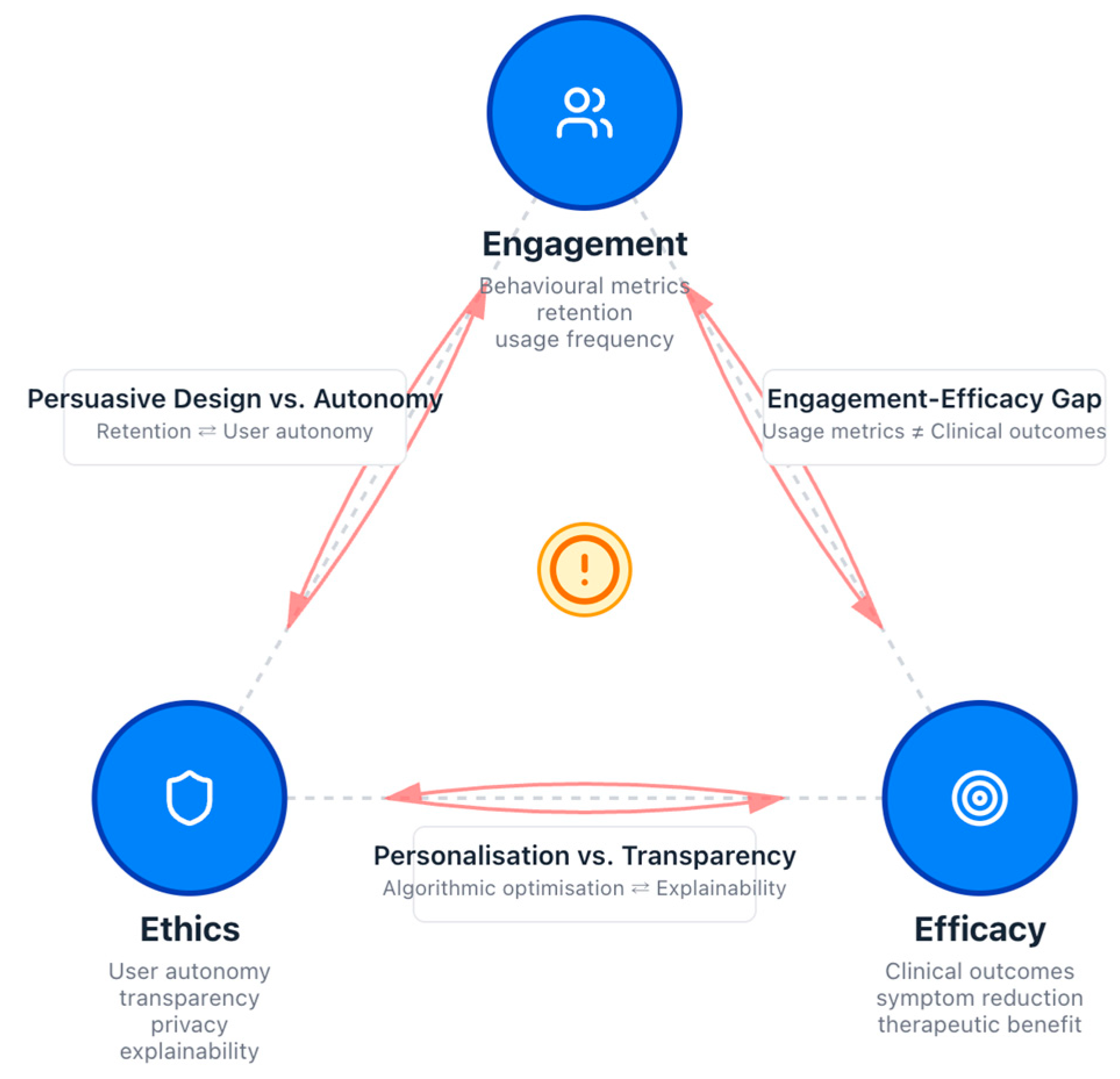

- (1)

- The Engagement–Efficacy Tension: This represents the ‘Engagement–Efficacy Gap’ identified in the literature, where design optimised for momentary behavioural adherence results in high ‘app engagement’ (e.g., logins, time-on-app) but fails to trigger the deep cognitive processing required for ‘therapeutic engagement’ and symptom reduction.

- (2)

- The Engagement–Ethics Tension: This occurs when persuasive mechanics, such as variable reward schedules or competitive leaderboards, leverage cognitive biases to sustain use. These risks cross the line from supportive nudging into cognitive manipulation, potentially undermining user autonomy or inducing psychological distress.

- (3)

- The Efficacy–Ethics Tension: This tension is frequently amplified by intelligent systems, where AI-driven personalisation relies on invasive data collection and ‘black-box’ algorithms. While such tailoring can increase clinical efficacy, it often creates a conflict with ethical principles of transparency, privacy, and user agency.

2. Theoretical Foundations of Gamification

2.1. Behaviourism and Operant Conditioning

2.2. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

2.3. The Fogg Behaviour Model (FBM)

- Motivation: This aligns with the drives discussed in SDT and Behaviourism. Fogg categorises core motivators into three pairs: Sensation (pleasure/pain), Anticipation (hope/fear), and Belonging (social acceptance/rejection). Gamification directly targets these, for instance, by offering rewards (pleasure) or creating leaderboards (social belonging).

- Ability: Fogg reframes ability as simplicity. A behaviour is more likely to be performed if it is easy to do. Gamification can increase a user’s ability by breaking down complex therapeutic tasks into smaller, more manageable steps, such as quests or levels, thereby reducing the required physical or mental effort.

- Prompt: A behaviour will not happen without a trigger or cue. Gamified systems are rich with prompts, from push notifications that remind users to complete a daily challenge to in-app visual cues that prompt the following action.

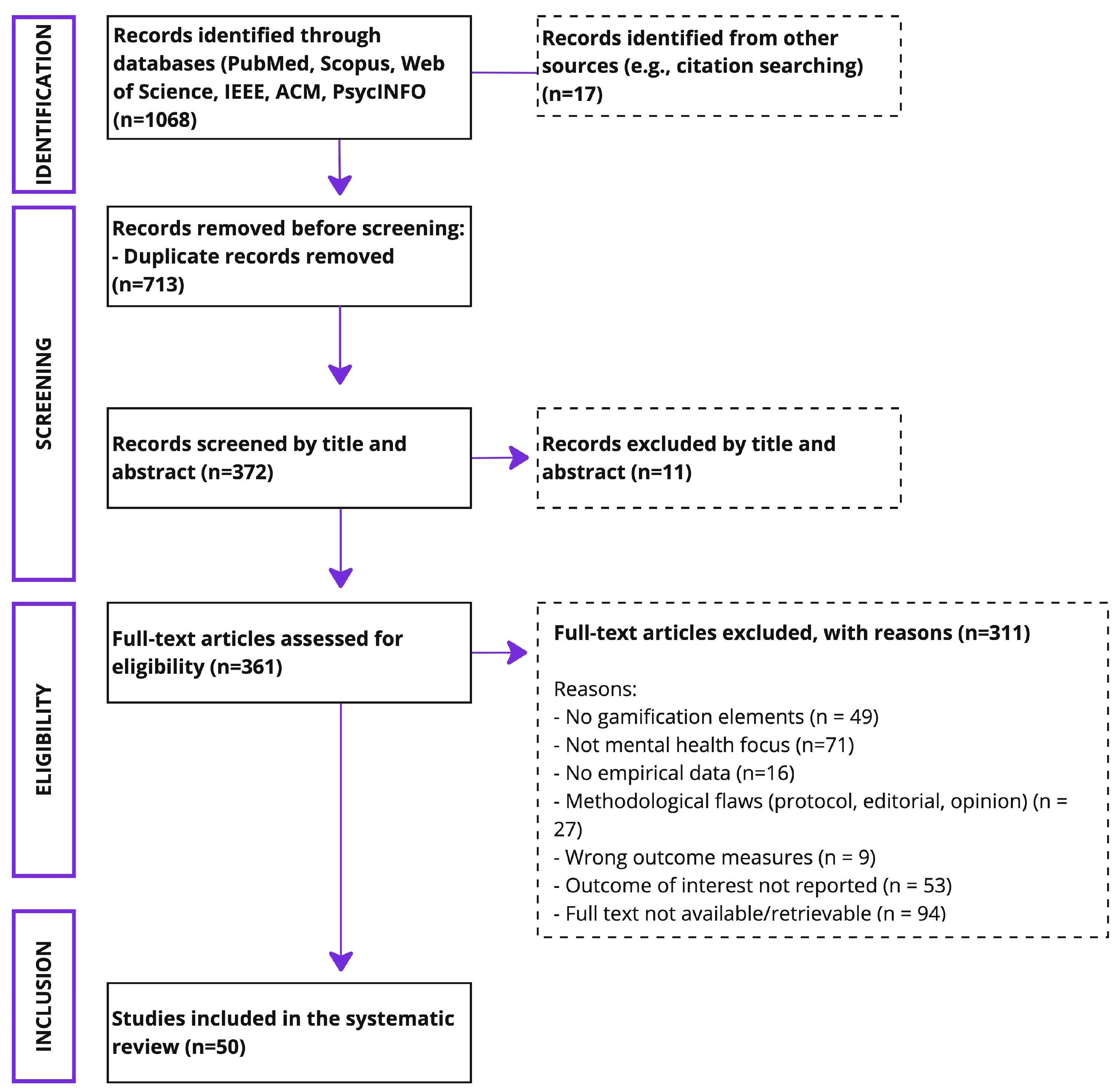

3. Methodology of Literature Selection

3.1. Search Strategy and Information Sources

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

3.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

4. The Engagement–Efficacy Gap: The First Tension of the Trilemma

| Study | Key Findings on Engagement | Key Findings on Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| [6] | High adherence (64.5%) and 42% higher retention in the gamified app group compared to the control group. | Significant improvements in resilience, anxiety, and depression in the gamified group. |

| [8] | Avatar customisation increased in-the-moment engagement and user identification with the intervention. | Customisation improved training efficacy and was associated with reduced anxiety. |

| [9] | A gamified Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) app for child anxiety led to increased usage and higher retention compared to a non-gamified version. | The gamified version resulted in improved therapeutic skill practice. |

| [25] | A meta-regression showed no significant effect of gamification on intervention adherence. | A meta-analysis found no significant difference in effectiveness for reducing depressive symptoms between gamified and non-gamified apps. |

| [10] | Engagement data was mixed; reward and progress elements were common, but metrics were inconsistent. | Positive effects on well-being and depressive symptoms, but heterogeneous and inconsistent results for anxiety and stress. |

| [28] | A systematic review found no statistically significant difference in adherence between different gamification features or the number of features. | The review did not conduct a meta-analysis of clinical efficacy but noted that usage data were not commonly reported, which limited the conclusions that could be drawn. |

5. The Ethical Landscape: The Second Tension of the Trilemma

6. AI as an Amplifier of the Trilemma

Explainable AI (XAI) as a Potential Mitigator

7. HCI as the Mediator of the Trilemma

- Human-to-Data Interaction: The user inputs data (e.g., a mood log) and receives a visualisation back. This can enhance competence but raises privacy concerns about the data being logged.

- Human-to-Human Interaction: The system mediates connections between people, such as in peer support forums or competitive leaderboards. While this can foster relatedness, leaderboards are a clear example of a design choice that prioritises engagement at the potential cost of ethical well-being (by inducing anxiety) and efficacy (by distracting from therapeutic goals).

- Human-to-AI Interaction: The user interacts with an intelligent agent, such as a therapeutic chatbot. The design of this interaction directly mediates the tension between personalised efficacy and the ethical risks of manipulation and a lack of genuine empathy.

- Human-to-Algorithm Interaction: The user interacts with the underlying game mechanics, such as levelling up or earning points. The design of these algorithms determines whether the motivation is primarily extrinsic (potentially undermining long-term efficacy) or intrinsic (supporting autonomy and competence).

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAD | Analysis of Agreement and Divergence |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy |

| DMHIs | Digital Mental Health Interventions |

| DTA | Digital Therapeutic Alliance |

| FBM | Fogg Behaviour Model |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| PDC | Persuasive Design Category |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCTs | Randomised Controlled Trials |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| UX | User Experience |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XR | Extended Reality |

Appendix A

Descriptive Summary of Included Studies

| Study | Engagement Metrics | Therapeutic Efficacy | Ethical Frameworks | Gamification Design Features | User Experience and Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | High engagement via smartphone serious games; frequent use reported | Positive psychological outcomes; varied symptom targets | Limited ethical discussion; focus on usability and engagement | Interactive, immersive, user-tailored game mechanics | Good adherence; self-administrable interventions |

| [10] | Mixed engagement data: reward and progress elements are common | Positive effects on well-being and depressive symptoms; heterogeneous for anxiety and stress | Ethics are briefly mentioned; need for rigorous designs | Rewards, sensations, and progress elements are prevalent | Variable retention; inconsistent engagement metrics |

| [5] | Increased engagement in paediatric populations compared to traditional therapy | Early evidence of therapeutic benefit for anxiety, depression, and ADHD | Ethical aspects are not deeply explored | Gamified video game-based interventions | Enhanced adherence relative to non-gamified treatments |

| [77] | Engagement is enhanced by goal setting, feedback, and social interaction | Improved patient outcomes across healthcare domains | Ethical concerns include autonomy, privacy, and addiction risks | Narrative immersion, progress tracking, and personalisation | Sustained participation linked to design features |

| [17] | Engagement is emphasised via the target audience and the user engagement focus. | Mechanisms of action linked to health effectiveness | Ethical tensions between healthcare and entertainment paradigms | Gamification, serious games, purpose-shifted entertainment games | User engagement is critical for intervention success |

| [17] | Focus on engagement through paradigm integration | Therapeutic effects linked to game mechanics | Ethical challenges in balancing entertainment and health goals | Customisation, gamification, serious game design | Engagement mediates efficacy; design impacts adherence |

| [78] | High completion rates: app used frequently in short sessions | Significant reductions in negative emotions and maladaptive coping | Ethical considerations include usability and feasibility | Gamified mobile app with metacognitive skill training | Positive user feedback: feasibility for RCTS confirmed |

| [6] | 64.5% adherence; higher retention than controls | Significant improvements in resilience, anxiety, and depression | Ethics is not the primary focus; it is implied in design | Gamified mobile app teaching psychological skills | High user retention and satisfaction reported |

| [79] | Gamification increased app usage frequency and points earned | Positive correlation between engagement and mental health improvement | Ethical issues were not explicitly addressed | Points, badges, leaderboards, gamification | Engagement is positively influenced by gamification |

| [8] | Avatar customisation increased in-the-moment engagement | Customisation improved training efficacy, reduced anxiety | Ethical implications implicit in user autonomy and personalisation | Avatar customisation as motivational design | Increased identification enhanced adherence and efficacy |

| [80] | The gaming component encouraged goal adherence in serious mental illness | Feasibility study underway; expected health improvements | Ethical focus on patient motivation, adherence, and autonomy | Rewards based on individualised goals | Early indications of good adherence and engagement |

| [9] | A gamified CBT app increased usage and retention in child anxiety | Improved skill practice and engagement compared to non-gamified | Ethical considerations include acceptability and usefulness | Interactive games, rewards, and a messaging interface | Higher engagement and retention than prior versions |

| [2] | Engagement improved via motivational dynamics in applied games | Promising evidence for depression treatment efficacy | Ethics are discussed in terms of research gaps and user needs | Variety of game types, including exergames and cognitive training | User-centred design emphasised for adherence |

| [81] | Moderate engagement; PC-based serious games | Moderate effect size on symptom improvement | Limited ethical discussion; focus on clinical outcomes | Goal-oriented and cognitive training games | Feasibility and accessibility issues noted |

| [12] | Engagement is discussed in the context of young people’s use | Ethical aspects are central; limited efficacy data | Comprehensive ethical framework, including privacy and autonomy | Serious gaming elements with co-design emphasis | Ethical integration linked to sustained use |

| [13] | Engagement is linked to social connection | Ethical concerns about harms and gaps | In-depth ethical analysis, including privacy and justice | Ethical design principles are recommended | User trust and safety are emphasised for adherence |

| [14] | Engagement increased, but with risks of addiction and privacy invasion | Ethical concerns about behavioural manipulation | Strong focus on ethical frameworks and privacy | Gamification risks highlighted | Calls for responsible and ethical gamification |

| [15] | Motivation and commitment improved via gamification | Ethical and moral aspects are critical in design | Framework for ethical gamification development | Balance of motivation and user well-being | Ethical design supports sustained engagement |

| [27] | Gamification increased motivation and enjoyment | Supported efficacy for depression, anxiety, and stress | Ethics briefly noted; focus on effectiveness | Combination of gaming and CBT techniques | Positive adherence linked to gamification |

| [26] | Engagement metrics varied; persuasive design principles analysed | Significant clinical improvements in mental health outcomes | Ethics not the primary focus: design principles evaluated | Use of persuasive design elements | Engagement data is inconsistently reported |

| [23] | Frequent use of customisation, narrative, and feedback elements | Positive outcomes in anxiety, depression, and stress reduction | Ethical considerations implicit in design choices | Extended reality and game-based intervention elements | User motivation supported by immersive features |

| [82] | High engagement in school-based gamified health promotion | Effective in reducing anxiety, depression, and burnout | Ethical issues addressed via CBT and neuropsychological integration | CBT and neuropsychological principles are embedded | Positive user adherence and behavioural outcomes |

| [74] | High retention (>90%) and adherence (>80%) in Ugandan adolescents | Trends toward symptom reduction; feasibility confirmed | Ethical acceptability emphasised via co-production | Narrative gamification with telephonic guidance | High acceptability and sustained use reported |

| [7] | Large-scale reach with moderate completion rates | Knowledge gains and positive user feedback | Ethical considerations implicit in accessibility | Interactive voice response game format | Strong acceptability: engagement improvements needed |

| [83] | Engagement is comparable between gamified and group CBT | Both interventions are effective for anxiety and depression | Ethics not primary focus: clinical effectiveness emphasised | Gamified self-guided CBT app and group training | Good adherence and symptom remission reported |

| [84] | The feasibility study showed good recruitment and retention | Small to large effect sizes on mental health measures | Ethical acceptability supported by qualitative feedback | ACT-based video game with therapeutic focus | Positive user experience and adherence |

| [18] | User feedback guided gamification design for engagement | Gamification enhanced intrinsic motivation and behavioural change | Ethical design integrated with behavioural theories | Personalisation, challenges, and assistance elements | High engagement and user satisfaction reported |

| [85] | VR gamified CBT increased engagement in university students | Reduced short-term anxiety; usability confirmed | Ethical considerations implicit in design | VR with CBT techniques and gamification | Positive user experience and usability |

| [86] | Gamified CBT app tailored for Arabic users | Reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms | Cultural and ethical tailoring emphasised | Gamified CBT elements adapted culturally | User satisfaction and symptom improvement |

| [87] | Gamification integrated with CBT in a narrative game | Supports depressive symptom reduction via engagement | Ethical review by CBT experts included | Narrative, verbal, physical, and social media gamification | Positive user engagement and learning |

| [20] | Gamification improved retention via rewards and levels | Increased intrinsic motivation and regular use | Ethical design stressed avoiding over-reliance on extrinsic motivators | Points, badges, and leaderboards used | User-centred design critical for sustained use |

| [75] | Cultural and clinical factors influence engagement | Feasibility and acceptance in Malaysian adults with depression | Ethical concerns about addiction and stigma are addressed | Storylines, therapist guidance, safety measures | Acceptance is linked to culturally sensitive design |

| [16] | Engagement varies with personalisation and gender factors | Effectiveness is influenced by study design and client needs | Ethical risks of over-engagement and addiction are discussed | Personalisation vs. standardisation debated | Tailored gamification is recommended for adherence |

| [88] | Increased gamification use during COVID-19: engagement rising | Supports mental health improvement during the pandemic | Ethics are briefly mentioned; there is a need for further research | Mobile and web-based gamified platforms | Engagement facilitated by remote access |

| [89] | A gamified educational game improved mental health literacy | Reduced stigma and increased awareness | Ethical focus on education and stigma reduction | Educational content integrated with gamification | Positive user feedback and community impact |

- Engagement Metrics:

- Therapeutic Efficacy:

- Ethical Frameworks:

- Gamification Design Features:

- User Experience and Adherence:

Appendix B

Critical Analysis and Synthesis of Strengths and Weaknesses in the Literature

| Aspect | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement Enhancement | Numerous studies have demonstrated that gamification significantly improves user engagement and retention in digital mental health interventions, leveraging motivational design elements such as rewards, progress tracking, and avatar customisation to sustain participation [6,8,20]. The incorporation of immersive technologies, such as virtual reality, further enhances engagement by providing interactive and personalised experiences [23,85]. | Despite positive indications, engagement metrics are inconsistently defined and reported, complicating cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses [10,26]. Over-reliance on extrinsic motivators may lead to user fatigue or disengagement over time, and few studies address long-term adherence beyond the initial novelty effects [14,20]. |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Evidence from randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses supports the efficacy of gamified interventions in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress across diverse populations, including paediatric and adult cohorts [4,81,83]. Gamification integrated with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques shows promise in enhancing skill acquisition and symptom improvement [9,86,87]. | Many studies suffer from small sample sizes, short follow-up periods, and heterogeneity in intervention components, limiting the robustness of efficacy claims [10,27]. The lack of standardised outcome measures and control conditions impedes definitive conclusions about the superiority of gamified versus non-gamified approaches [2,11]. |

| Ethical Considerations | Recent reviews emphasise the importance of addressing privacy, autonomy, accessibility, and cultural sensitivity in gamified mental health interventions, advocating for co-design and ongoing ethical reflection throughout the development and implementation process [12,13,15]. Some studies highlight the potential for gamification to empower users and reduce stigma, particularly among vulnerable youth populations [12,89]. | Ethical discussions are often limited to research ethics, neglecting broader socio-political and systemic implications such as regulatory gaps, data surveillance, and potential for addiction [13,14]. There is a paucity of comprehensive frameworks guiding ethical gamification design, and vulnerability is frequently addressed pragmatically rather than holistically [12,13]. |

| Design Principles and Game Mechanics | The literature identifies key game elements -such as narrative immersion, customisation, feedback, and social interaction-that contribute to both engagement and therapeutic outcomes [17,18,23]. Frameworks integrating healthcare and entertainment paradigms facilitate the development of interventions that balance clinical effectiveness with user appeal [17,18]. | There is inconsistency in the application and reporting of game mechanics, with limited empirical evidence delineating which elements or combinations optimise outcomes [10,11]. Many interventions lack user-centred design processes or fail to adapt to diverse cultural contexts, reducing accessibility and relevance [75,92]. |

| User Experience and Adherence Factors | Studies underscore the role of personalised, culturally sensitive content and intuitive interfaces in promoting sustained use and adherence [74,75]. Gamification strategies that foster intrinsic motivation, such as avatar identification and meaningful challenges, enhance user experience and intervention uptake [8,18]. | Attrition remains a significant challenge, with many interventions experiencing high dropout rates and limited long-term engagement data [6,78]. User fatigue and complexity of gameplay can deter some populations, particularly those with cognitive or motivational impairments [20,75]. |

| Methodological Rigour and Reporting | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide valuable syntheses of existing evidence, highlighting positive trends and identifying research gaps [26,81]. The use of randomised controlled trials in recent studies strengthens causal inferences regarding the effects of gamification [6,83]. | The field is characterised by methodological heterogeneity, including variable study designs, inconsistent outcome measures, and insufficient reporting of engagement metrics [10,26]. Many studies lack rigorous control groups or fail to isolate the specific impact of gamification components [2,11]. |

| Integration with Therapeutic Frameworks | Gamified interventions often incorporate established therapeutic models such as CBT and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), enhancing clinical relevance and user skill development [9,84,87]. The combination of gamification with evidence-based therapy supports both engagement and efficacy [16,86]. | There is limited exploration of how gamification interacts with the therapeutic mechanisms of action, and few studies systematically evaluate the mediating role of gamified elements on clinical outcomes [17,18]. The balance between entertainment and therapeutic goals remains a challenge, potentially compromising the fidelity of the intervention [17,92]. |

Appendix C

Thematic Review of Literature

| Theme | Appears In | Theme Description |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement and User Motivation | 35/50 Papers | Gamification significantly enhances user engagement and motivation in digital mental health interventions by leveraging game elements such as rewards, progress tracking, and personalisation. Enhanced engagement contributes to better adherence and increased interaction time, which are essential for the success of interventions across age groups and mental health conditions [1,6,8,10,20,26]. Studies report that gamification improves intrinsic motivation and regular usage patterns, although challenges such as user fatigue and over-reliance on extrinsic rewards remain [15,20]. |

| Therapeutic Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes | 30/50 Papers | Empirical evidence suggests that gamified digital mental health interventions can improve clinical outcomes, including reductions in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as increases in resilience and psychological flexibility [5,6,10,27,81,83]. Meta-analyses and RCTs demonstrate moderate to large effect sizes favouring gamified approaches over control or traditional treatments. However, heterogeneity in study designs and outcome measures limits direct comparison and highlights the need for standardised efficacy assessments [26,81]. |

| Ethical Considerations and Challenges | 22/50 Papers | Ethical issues such as privacy, data security, autonomy, inclusivity, and potential for addiction are critical concerns in gamified mental health interventions [12,13,14,15]. Literature emphasises the need for ongoing ethical reflection, co-design with vulnerable populations, and the development of guidelines to mitigate risks while promoting empowerment and accessibility. The regulatory vacuum and socio-political implications reveal opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration [12,13]. |

| Design Principles and Game Mechanics | 28/50 Papers | Effective gamification relies on design elements such as narrative immersion, customisation, feedback, challenge balancing, and social features that promote sustained engagement and therapeutic benefits [1,8,18,23,77]. Personalisation and customisation, such as avatar creation, enhance identification and efficacy, especially among users with lower satisfaction related to relatedness [8,18,23]. Incorporating behavioural theories and user feedback in design improves relevance and adherence [18]. |

| User Experience and Intervention Adherence | 25/50 Papers | User experience factors strongly mediate adherence to gamified mental health interventions. Positive usability, perceived usefulness, and psychological safety encourage sustained participation [74,78,80,84]. Attrition remains a challenge, but gamification features, such as rewards and interactive content, can help mitigate dropout rates. The need for culturally sensitive and accessible designs is highlighted to support diverse users [74,75]. |

| Co-Design and Cultural Tailoring | 15/50 Papers | Recent studies advocate for co-design approaches that involve target users and clinical experts to ensure cultural sensitivity and contextual appropriateness in gamified interventions [12,18,74,75,93]. Tailoring content and mechanics to specific populations increases acceptability and effectiveness, particularly in low-resource or diverse cultural settings [74,75]. |

| Integration of Therapeutic Frameworks (e.g., CBT, ACT) | 17/50 Papers | Gamification is often integrated with established therapeutic models, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, to enhance skills practice and symptom management [9,82,84,86,87]. These integrations promote active learning, behavioural activation, and coping strategy development through interactive and engaging game mechanics. Effectiveness is supported by increased skill retention and clinical symptom improvement [9,84]. |

| Technology Platforms and Accessibility | 20/50 Papers | Smartphone-based platforms dominate gamified mental health interventions due to their ubiquity, versatility, and connectivity, facilitating access anytime, anywhere [1,6,7,80]. Emerging technologies, such as Virtual Reality and Extended Reality, show promise in immersive therapeutic experiences but require further research on scalability and cost-effectiveness [23,85,94]. Accessibility challenges persist, particularly in low-resource regions, calling for simplified and culturally adapted solutions [7,75]. |

| Potential Risks and Limitations of Gamification | 12/50 Papers | Despite benefits, gamification poses risks including user addiction, privacy invasion, disengagement, and overemphasis on extrinsic rewards, which may undermine intrinsic motivation [14,15,20]. Some studies have noted limited long-term engagement and the need to strike a balance between entertainment and therapeutic goals. Addressing these limitations requires ethical design and user education [14,20]. |

| Economic and Policy Implications | 8/50 Papers | The scalability and cost-effectiveness of gamified digital mental health tools suggest a potential for broad healthcare impact, but economic evaluations and policy frameworks are underdeveloped [75,95,96]. Integration into healthcare systems demands evidence of efficacy, safety, and ethical adherence alongside strategies to ensure equitable access and sustainable implementation [95,96]. |

| Social and Community Impact | 10/50 Papers | Gamified interventions can foster social connection, reduce stigma, and promote mental health literacy through community engagement and multiplayer or collaborative features [13,89]. However, social isolation and miscommunication risks persist, necessitating careful design of social components [13,89]. |

| Research Gaps and Future Directions | 15/50 Papers | The field calls for standardisation of engagement metrics, rigorous study designs, expanded demographic representation, and exploration of the underlying mechanisms of gamification effects [10,11,26]. Emerging calls emphasise interdisciplinary collaboration, ethical frameworks, and longitudinal research to optimise and safely scale gamified mental health interventions [12,13,18]. |

Appendix D

Chronological Evolution of Research Directions

| Year Range | Research Direction | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2012–2015 | Early Ethical and Feasibility Foundations | Initial research explored ethical challenges of game-based interventions, especially for vulnerable groups, emphasising the need for trust and careful data handling. Early randomised trials evaluated gamified self-help tools targeting depression symptoms, establishing preliminary evidence of digital interventions’ potential. |

| 2017–2019 | Emergence of Serious Games and Gamification Frameworks | Studies reviewed the status and effectiveness of serious games, highlighting their accessibility, feasibility, and moderate clinical impact across various mental disorders. Integrative frameworks that bridge healthcare and entertainment paradigms were proposed to guide development, with growing attention to motivational design, such as avatar customisation, to improve engagement and efficacy. |

| 2020–2022 | Development of Gamified CBT and mHealth Applications | Research has advanced in integrating gamification into cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) via mobile and digital platforms, showing improved engagement and retention in child and adult populations. Studies developed narrative-driven and personalised gamified interventions, emphasising user experience and preliminary efficacy while beginning to address cultural adaptation and design challenges. |

| 2023–2024 | Systematic Reviews, Efficacy, and Ethical Considerations | Comprehensive systematic reviews and meta-analyses assessed the efficacy of gamified digital mental health interventions, revealing positive impacts on depression, anxiety, and resilience across age groups. Ethical concerns gained prominence, with calls for the ongoing integration of ethical practices throughout development and deployment, alongside detailed analysis of game mechanics and design principles that influence engagement and clinical outcomes. |

| 2024–2025 | Advanced Technologies and Scalability in Gamified Mental Health | Recent studies focus on immersive technologies, such as virtual and extended reality, combined with gamification, to enhance intrinsic motivation and therapeutic impact. Large-scale implementations in diverse global contexts demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability, while research addresses issues such as retention, cultural sensitivity, and ethical dilemmas. Emerging critiques highlight the dark side of gamification, advocating for responsible frameworks balancing engagement with privacy and user autonomy. |

Appendix E

Analysis of Agreement and Divergence in the Literature

| Comparison Criterion | Studies in Agreement | Studies in Divergence | Potential Explanations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement Metrics | Gamification consistently increases user engagement, retention, and adherence across diverse digital mental health platforms, using mechanisms such as rewards, points, badges, and narrative immersion [1,6,8,20,26]. Customisation and personalisation, especially, boost momentary engagement and sustained use [8,18]. | Some studies have noted challenges with long-term engagement and user fatigue, highlighting the risk of overreliance on extrinsic motivators [14,20]. Differences in engagement measurement and reporting complicate comparisons, as some studies report no significant association between persuasive design elements and engagement [26]. Limited data exist on engagement for specific vulnerable groups or low-resource settings [7]. | Variability in study design, metrics used, population differences, and intervention duration contributes to mixed findings. Longer trials and standardised engagement metrics are lacking. |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Positive therapeutic outcomes, including symptom reduction and improvements in resilience, are commonly reported for gamified digital mental health interventions across various age groups and settings [4,5,6,10,27,81,84]. Gamified CBT and serious games show efficacy in depression and anxiety management [9,86,87]. | Efficacy results are heterogeneous for some outcomes, like anxiety, stress, and life satisfaction [10,11], and vary by mental health condition and population. Some studies report moderate effects, while others indicate small or preliminary effects, often due to the constraints of small samples or pilot designs [4,8,84]. Comparisons with non-gamified or traditional interventions yield mixed results [83]. | Differences in sample size, study design (RCT vs. pilot), age groups, and intervention content explain variability. Lack of standardised outcome measures is a factor. |

| Ethical Frameworks | There is broad recognition of the importance of ethical considerations, such as privacy, autonomy, inclusivity, and vulnerability, in gamified mental health interventions [12,13,15,75]. Calls for co-design, ongoing ethical reflection, and integration of ethics throughout development are common [12,91]. | The depth and focus of ethical discussions vary. Some reviews focus on research ethics and privacy [12], while others critique insufficient attention to socio-political contexts and long-term ethical risks such as addiction and surveillance [13,14,15]. Practical guidance and regulatory frameworks remain underdeveloped [13,15]. Ethical issues are often addressed pragmatically rather than theoretically [12]. | Differences arise due to disciplinary perspectives (e.g., technical vs. humanities), regional regulatory environments, and research priorities emphasising feasibility over ethics. |

| Gamification Design Features | Reward systems, progress tracking, customisation, narrative immersion, and feedback loops are commonly identified as effective game mechanics that promote engagement and efficacy [1,8,17,18,23]. The integration of cognitive and behavioural therapy elements with gamification enhances the utility of interventions [9,87]. | Some studies emphasise the tension between healthcare and entertainment paradigms, which can complicate design and limit commercial adoption [7]. There is debate on the optimal quantity and combination of game elements, with no consensus on which features best balance engagement and efficacy [10,11]. Social and multiplayer elements are underutilised despite their potential benefits [23]. Complexity and accessibility concerns affect design choices in some cultural contexts [75]. | Divergences arise from the needs of the target population, cultural factors, technological constraints, and differing theoretical frameworks that guide design. |

| User Experience and Adherence | Positive user experience, motivation, and adherence are reported in gamified interventions, which are aided by personalisation, ease of use, and the relevance of content [20,78,79,84]. Co-design approaches enhance acceptability and user satisfaction, particularly among vulnerable populations [93]. | Attrition and asymmetric dropout are common challenges, particularly in randomised controlled trials and longer interventions [6,78]. Some studies report limited adherence due to complexity, lack of guidance, or cultural mismatch [74,75]. Variability in qualitative assessments and limited reporting standards make cross-study comparisons difficult [20,26]. | Differences in intervention duration, population characteristics, cultural adaptation, and the presence of support or guidance influence adherence and experience outcomes. |

Appendix F

Theoretical and Practical Implications

- Theoretical Implications

- The synthesis of current research supports the theoretical premise that gamification enhances user engagement in digital mental health interventions by leveraging intrinsic motivational dynamics such as reward systems, narrative immersion, and customisation, which align with established behavioural and cognitive theories of motivation and learning [1,8,23]. This confirms that gamification is a viable mechanism for increasing adherence and therapeutic interaction.

- Evidence indicates that specific game mechanics, including avatar customisation and feedback loops, not only improve engagement but also directly contribute to intervention efficacy by fostering identification and emotional investment, particularly among users with lower baseline psychological needs satisfaction [8,18]. These findings nuance existing theories by highlighting the mediating role of user experience factors in therapeutic outcomes.

- The integration of gamification with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) frameworks demonstrates a promising theoretical convergence, suggesting that gamified elements can effectively operationalise therapeutic techniques in digital formats, thereby enhancing skill acquisition and application [9,84,87].

- The reviewed literature reveals a tension between the healthcare and entertainment paradigms in gamified mental health intervention development, underscoring the need for integrative frameworks that balance clinical efficacy with engaging game design principles [17]. This challenges traditional intervention development models and calls for interdisciplinary theoretical approaches.

- Ethical considerations emerge as a critical theoretical dimension, with current frameworks often limited to research ethics and privacy concerns, while broader socio-political and cultural implications remain underexplored [12,13]. This gap suggests the necessity to expand ethical theories to encompass the social embeddedness and long-term impacts of gamified mental health technologies.

- The role of social dynamics, such as multiplayer and collaborative features, remains underutilised in current gamified interventions, indicating a theoretical opportunity to incorporate social cognitive and community engagement theories to enhance motivation and therapeutic outcomes further [23].

- Practical Implications

- For industry practitioners, the findings emphasise the importance of user-centred design that incorporates personalisation, adaptive difficulty, and meaningful reward systems to sustain engagement and improve clinical efficacy in digital mental health products [1,20,26]. This calls for iterative development processes that involve end-user feedback and behavioural data analytics.

- Policymakers and healthcare providers should recognise gamified digital mental health interventions as scalable, cost-effective adjuncts or alternatives to traditional therapies, particularly in low-resource settings and among populations with limited access to conventional care [7,75,83]. Integration into existing care pathways requires attention to cultural sensitivity and clinical oversight to ensure seamless care.

| Area of Limitation | Description of Limitation | Papers with Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Small Sample Sizes | Many studies suffer from limited sample sizes, which restricts the statistical power and generalizability of findings. This limitation undermines external validity and may lead to overestimation or underestimation of intervention effects. | [78,79,84] |

| Heterogeneous Methodologies | The diversity in study designs, outcome measures, and intervention components complicates cross-study comparisons and meta-analyses. This methodological constraint limits the ability to draw consistent conclusions about efficacy and engagement. | [10,11] |

| Limited Long-Term Data | A lack of longitudinal follow-up data restricts understanding of sustained engagement, efficacy, and ethical implications over time. This gap weakens claims about the durability of the benefits of gamified interventions. | [12,77,81] |

| Geographic and Cultural Bias | Most research is concentrated in high-income or Western contexts, limiting the applicability of findings to diverse populations. This geographic bias affects the external validity and cultural relevance of gamified mental health interventions. | [7,74] |

| Insufficient Ethical Considerations | Ethical issues, such as privacy, autonomy, and potential harms, are often underexplored or narrowly interpreted, which limits a comprehensive understanding of the risks and mitigation strategies associated with gamified mental health technologies. | [12,13,14,15] |

| Lack of Standardised Taxonomies | The absence of standardised frameworks or taxonomies for gamification elements and mechanisms hinders systematic evaluation and replication, reducing clarity on which components drive engagement and efficacy. | [10,11] |

| Overreliance on Self-Report Measures | The predominant use of self-reported data introduces biases and limits the objective assessment of engagement and clinical outcomes, thereby affecting the reliability and validity of the findings. | [27,78,79] |

| Limited Focus on Social and Multiplayer Features | Many interventions neglect social dynamics and multiplayer elements, which may be critical for engagement and therapeutic impact, thereby limiting the scope of gamification’s potential benefits. | [23] |

| Underrepresentation of Vulnerable Groups | Vulnerable populations, including those with severe mental illness or social exclusion, are often underrepresented, limiting insights into intervention accessibility, acceptability, and ethical challenges for these groups. | [12,91] |

| Technological Constraints | Emerging technologies, such as VR and mobile platforms, face limitations including hardware discomfort, immersion quality, and accessibility, which can negatively impact user experience and intervention effectiveness. | [3,85,94] |

Appendix G

Gaps and Future Research Directions

| Gap Area | Description | Future Research Directions | Justification | Research Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardisation of Engagement Metrics | Engagement metrics in gamified digital mental health interventions are inconsistently defined and reported, limiting comparability across studies. | Develop and adopt standardised, validated engagement metrics and reporting guidelines specific to gamified mental health interventions to enable meta-analyses and cross-study comparisons. | Consistent engagement measurement is essential for understanding the true impact of gamification on adherence and therapeutic outcomes [10,26]. | High |

| Long-term Efficacy and Adherence | Most studies focus on short-term outcomes with limited data on sustained engagement, adherence, and clinical efficacy over extended periods. | Conduct longitudinal randomised controlled trials with follow-ups beyond six months to assess the durability of engagement and therapeutic benefits of gamified interventions. | Understanding the long-term effects is critical to evaluating real-world utility and preventing novelty effects from fading [10,20,78]. | High |

| Comprehensive Ethical Frameworks | Ethical discussions are often limited to research ethics, neglecting broader socio-political, privacy, and addiction concerns in gamified mental health tools. | Develop comprehensive, interdisciplinary ethical frameworks integrating privacy, autonomy, addiction risk, cultural sensitivity, and regulatory considerations for gamified mental health interventions. | Ethical oversight is necessary to safeguard vulnerable users and ensure the responsible design and deployment of systems [12,13,14]. | High |

| Mechanisms of Gamification Impact on Therapeutic Outcomes | The specific mechanisms by which gamification elements influence clinical efficacy and behaviour change remain underexplored. | Employ mixed-methods and mediation analyses to isolate how individual game mechanics (e.g., rewards, customisation) affect psychological processes and symptom improvement. | Clarifying mechanisms will optimise intervention design and maximise therapeutic impact [17,18]. | Medium |

| Cultural Adaptation and Inclusivity | Limited research addresses the cultural tailoring and inclusivity of gamified mental health interventions, which can impact accessibility and relevance across diverse populations. | Design and evaluate culturally adapted, gamified interventions that incorporate participatory co-design and involve diverse user groups, particularly in low-resource settings. | Cultural sensitivity enhances the acceptability, engagement, and equity in mental healthcare delivery [74,75,86]. | High |

| Integration of Emerging Technologies | Emerging technologies like virtual reality (VR) and extended reality (XR) show promise but lack rigorous evaluation and standardised design principles in gamified mental health. | Conduct controlled trials assessing VR/XR gamified interventions, develop best practice guidelines for immersive gamification design, and investigate user experience and clinical outcomes. | VR/XR can enhance immersion and engagement but require validation to ensure efficacy and usability [3,23,85]. | Medium |

| User-Centred and Participatory Design | Many interventions lack systematic user-centred design and co-design processes, limiting personalisation and user motivation. | Implement iterative co-design frameworks that involve end-users and clinicians to tailor gamification features, enhance usability, and address user needs and preferences. | User involvement improves adherence, satisfaction, and ethical acceptability [12,18,93]. | High |

| Balancing Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation | Over-reliance on extrinsic motivators (e.g., points, badges) may lead to user fatigue and reduced long-term engagement. | Investigate gamification strategies that foster intrinsic motivation, such as the use of meaningful narratives and avatar identification, and evaluate their impact on sustained engagement. | Enhancing intrinsic motivation is key to preventing disengagement and promoting lasting behaviour change [12,18,20]. | Medium |

| Standardised Taxonomy of Game Elements | A lack of a comprehensive taxonomy categorising game elements and their therapeutic roles hinders systematic research and design. | Develop and validate a taxonomy of gamification components specifically tailored to mental health interventions, linking these elements to relevant psychological constructs and outcomes. | A taxonomy facilitates systematic evaluation, replication, and optimisation of gamified interventions [10,11]. | Medium |

| Addressing Attrition and Dropout | High attrition rates and dropout remain challenges, with insufficient strategies tested to mitigate these issues in gamified mental health apps. | Design and test engagement strategies (e.g., adaptive difficulty, social features) to reduce attrition and analyse predictors of dropout to inform personalised retention approaches. | Reducing attrition is essential for the effectiveness and real-world applicability [6,7,78]. | High |

Appendix H

Overall Synthesis and Conclusion

References

- Gomez-Cambronero, A.; Mann, A.; Mira, A.; Doherty, G.; Casteleyn, S. Smartphone-based serious games for mental health: A scoping review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 84047–84094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.; Bavin, L.; Stasiak, K.; Hermansson-Webb, E.; Merry, S.N.; Cheek, C.; Lucassen, M.; Lau, H.M.; Pollmuller, B.; Hetrick, S.E. Serious games and gamification for mental health: Current status and promising directions. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Serious games for improving mental health: Status and prospects. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2024, 64, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, B.R.; Sisk, M.R.; McGuire, J. Efficacy of gamified digital mental health interventions for pediatric mental health conditions. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 1136–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, B.R.; Sisk, M.R.; McGuire, J.F. 2.56 Gamified digital mental health interventions as therapeutics for common pediatric mental health conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 62, S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.; Saunders, R.; Jefferies, P.; Seely, H.D.; Pössel, P.; Lüttke, S. The impact of a gamified mobile mental health app (eQuoo) on resilience and mental health in a student population: Large-scale randomised controlled trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e47285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkley, C.; Nyakonda, C.N.; Kuthyola, K.; Ndlovu, P.; Lee, D.; Dallos, A.; Kofi-Armah, D.; Obeng, P.; Merrill, K.G. A gamified digital mental health intervention across six sub-Saharan African countries: A cross-sectional evaluation of a large-scale implementation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birk, M.V.; Mandryk, R.L. Improving the efficacy of cognitive training for digital mental health interventions through avatar customisation: Crowdsourced quasi-experimental study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e10133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramana, G.; Parmanto, B.; Lomas, J.; Lindhiem, O.; Kendall, P.C.; Silk, J.S. Using mobile health gamification to facilitate cognitive behavioural therapy skills practice in child anxiety treatment: Open clinical trial. JMIR Serious Games 2018, 6, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzghoul, B. The Effectiveness of Gamification in Changing Health-related Behaviors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open Public Health J. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschentrup, L.; Steimer, P.A.; Dadaczynski, K.; Call, T.M.; Fischer, F.; Wrona, K.J. Effectiveness of gamified digital interventions in mental health prevention and health promotion among adults: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahl, W.; Motta, V.; Woodcock, K.; Rubeis, G. Gamified digital mental health interventions for young people: Scoping review of ethical aspects during development and implementation. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e64488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavarini, G.; Reay, E.; Smith, L. Ethical implications of applied digital gaming interventions for mental health: A systematic review and critical appraisal. INPLASY Protocol 2023, 202330035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, U. The dark side of gamification. In Ethical Implications of AI in Digital Marketing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; Chapter 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.; Reis, S.S. Ethical issues of gamification in healthcare: The need to be involved. In Handbook of Research on Solving Modern Healthcare Challenges with Gamification; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Ebrahimi, O.V. Gamification: A novel approach to mental health promotion. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukka, L.; Palva, J.M. The development of game-based digital mental health interventions: Bridging the paradigms of health care and entertainment. JMIR Serious Games 2023, 11, e42173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewko, M.; Shaigetz, V.G.; Smith, M.S.D.; Kohlenberg, E.; Ahmadi, P.; Hernández, M.E.H.; Proulx, C.; Cabral, A.; Segado, M.; Chakrabarty, T.; et al. Considering theory-based gamification in the co-design and development of virtual reality cognitive remediation for depression (bwell-d). JMIR Serious Games 2025, 13, e59514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, B.F. Science and Human Behavior; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Nagvanshi, S.; Munshi, A.; Bhatnagar, S. Gamification and retention in mental health apps. In Ethical Implications of AI in Digital Marketing; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; Chapter 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K.M. The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Game-Based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, F.; Abreu, A. Designing immersive healing: Exploring extended reality game-based intervention elements for mental health. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 13th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), Manchester, UK, 6–8 August 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B.J. A behavior model for persuasive design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Claremont, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2009; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, S.; Byrne, K.A.; Tibbett, T.P.; Pericot-Valverde, I. Examining the effectiveness of gamification in mental health apps for depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e32199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, L.; Hinton, J.D.X.; Bajaj, K.; Boyd, L.; O’Sullivan, S.; Sorenson, R.P.; Bell, I.; Vega, M.; Liu, V.; Peters, W.; et al. A meta-analysis of persuasive design, engagement, and efficacy in 92 RCTs of mental health apps. NPJ Digit Med. 2025, 8, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falero, S.S. Computer-based cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for depression, anxiety, and stress disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2024, 17, 885–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Deterding, S.; Kuhn, K.A.; Staneva, A.; Stoyanov, S.; Hides, L. Gamification for health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv. 2016, 6, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Msallam, S.; Xi, N.; Hamari, J. Unethical Gamification: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 3–6 January 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, C.; Razavian, M. Ethics of gamification in health and fitness-tracking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, I.; Silveira, M.S. Potential adverse effects caused by gamification elements in mhealth apps. J. Braz. Comput. Soc. 2024, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundus, H.; Chhabra, C.; Kaur, H.; Jain, S.; Shankar, M. Enhancing the Future of Personalized Health Care Through Artificial Intelligence and Gaming. In Psychology in the Digital Era: Navigating the Intersection of Minds and Machines; Redshine Publications: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Olawade, D.B.; Wada, O.Z.; Odetayo, A.; David-Olawade, A.C.; Asaolu, F.T.; Eberhardt, J. Enhancing mental health with artificial intelligence: Current trends and future prospects. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 3, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Abuelezz, I.; Hassan, A.; AlSammarraie, A.; Alhuwail, D.; Irshaidat, S.; Serhan, H.A.; Ahmed, A.; Alrazak, S.A.; Househ, M. Artificial intelligence–driven serious games in health care: Scoping review. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e39840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Saleh, K.B.; Badreldin, H.A.; et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolks, D.; Schmidt, J.; Kühn, S. The role of AI in serious games and gamification for health: Scoping review. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e48258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadi, M.R.; Sillekens, T.; Metselaar, S.; van Balkom, A.J.; Bernstein, J.; Batelaan, N.M. Exploring the ethical challenges of conversational AI in mental health care: Scoping review. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e60432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeidnia, H.R.; Fotami, S.G.H.; Lund, B.; Ghiasi, N. Ethical considerations in artificial intelligence interventions for mental health and well-being: Ensuring responsible implementation and impact. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, V.K. The emergence of AI in mental health: A transformative journey. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 22, 1867–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.K. Exploring digital therapeutics for mental health: AI-driven innovations in personalized treatment approaches. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 24, 2733–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticksen, D.; Prasad, P. AI and Mental Health: Reviewing the Landscape of Diagnosis, Therapy, and Digital Interventions; Alpha Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, F.; Alam, L.F.; Vivas, R.R.; Wang, J.; Whei, S.J.; Mehmood, S.; Sadeghzadegan, A.; Lakkimsetti, M.; Nazir, Z. The role of artificial intelligence in identifying depression and anxiety: A comprehensive literature review. Cureus 2024, 16, e56472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espejo, G.; Reiner, W.; Wenzinger, M. Exploring the role of artificial intelligence in mental healthcare: Progress, pitfalls, and promises. Cureus 2023, 15, e44748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, S.; Depp, C.A.; Lee, E.; Nebeker, C.; Tu, X.; Kim, H.; Jeste, D.V. Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: An overview. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, A.; Gupta, A.; de Sousa, A. Artificial intelligence in positive mental health: A narrative review. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1280235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B. The promise of explainable AI in digital health for precision medicine: A systematic review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharwardy, S.; Ramachandran, M.; Leonard, S.A.; Gunaseelan, A.; Lyell, D.J.; Darcy, A.; Robinson, A.; Judy, A. Feasibility and impact of a mental health chatbot on postpartum mental health: A randomized controlled trial. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2023, 3, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrier, U.; Warrier, A.; Khandelwal, K. Ethical considerations in the use of artificial intelligence in mental health. Egypt. J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2023, 59, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, B. Privacy and artificial intelligence: Challenges for protecting health information in a new era. BMC Med. Ethics 2021, 22, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustgarten, S.D.; Garrison, Y.L.; Sinnard, M.T.; Flynn, A. Digital privacy in mental healthcare: Current issues and recommendations for technology use. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennella, C.; Maniscalco, U.; Di Pietro, G.; Esposito, M. Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solanki, P.; Grundy, J.; Hussain, W. Operationalising ethics in artificial intelligence for healthcare: A framework for AI developers. AI Ethics 2023, 3, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D. Ethical and legal considerations in healthcare AI: Innovation and policy for safe and fair use. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 241873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktas, P.; Grzybowski, A. Shaping the future of healthcare: Ethical clinical challenges and pathways to trustworthy AI. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.M.; Choma, M.A.; Onofrey, J.A. Bias in medical AI: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Bjarnadóttir, M.V.; Rhue, L.A.; Dugas, M.; Crowley, K.; Clark, J.; Gao, G. Addressing algorithmic bias and the perpetuation of health inequities: An AI bias aware framework. Health Policy Technol. 2023, 12, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X. The ethical challenges of AI-based mental health interventions: Toward a layered accountability framework. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2025, 81, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ruijs, N.; Lü, Y. Ethics & AI: A systematic review on ethical concerns and related strategies for designing with AI in healthcare. AI 2023, 4, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, U.; Jakhar, S.; Prakash, M.; Nepal, A. AI in mental health: A review of technological advancements and ethical issues in psychiatry. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2025, 46, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elendu, C.; Amaechi, D.C.; Elendu, T.C.; Jingwa, K.A.; Okoye, O.K.; Okah, M.J.; Ladele, J.A.; Farah, A.H.; Alimi, H.A. Ethical implications of AI and robotics in healthcare: A review. Medicine 2023, 102, e36671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, J.; Fantus, S. Medical artificial intelligence ethics: A systematic review of empirical studies. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231186064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amedior, N.C. Ethical implications of artificial intelligence in the healthcare sector. Adv. Multidiscip. Sci. Res. J. Publ. 2023, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathni, R.K. Beyond algorithms: Ethical implications of AI in healthcare. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2024, 81, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharati, S.; Mondal, M.R.H.; Podder, P. A Review on Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare: Why, How, and When? IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 1429–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Alizadehsani, R.; Çifçi, M.A.; Kausar, S.; Rehman, R.; Mahanta, P.; Bora, P.K.; Almasri, A.; Alkhawaldeh, R.S.; Hussain, S.; et al. A review of explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.; Manzoor, A.; Qureshi, M.D.M.; Qureshi, M.A.; Rashwan, W. Unveiling explainable AI in healthcare: Current trends, challenges, and future directions. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L.; Leo, D.D. Human-computer interaction in digital mental health. Informatics 2022, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovák, P.; Munson, S.A. HCI contributions in mental health: A modular framework to guide psychosocial intervention design. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouin-Lachance, A.; Capolupo, J.; Laplante, C.; Hudon, A. Does the digital therapeutic alliance exist? Integrative review. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e69294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, A.F.; Hagemann, S.; Trinidad, S.B.; Vigil-Hayes, M. Human-to-computer interactivity features incorporated into behavioral health mhealth apps: Systematic search. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e44926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhail, M.A.; Alturki, N.; Thomas, J.; Alkhalifa, A.K.; Alshardan, A. Human-human vs human-AI therapy: An empirical study. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 6841–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maadi, M.; Khorshidi, H.A.; Aickelin, U. A review on human–AI interaction in machine learning and insights for medical applications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehbozorgi, R.; Zangeneh, S.; Khooshab, E.; Nia, D.H.; Hanif, H.; Samian, P.; Yousefi, M.; Hashemi, F.; Vakili, M.; Jamal-imoghadam, N.; et al. The application of artificial intelligence in the field of mental health: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo, J.R.; Nabulumba, C.; Sikoti, D.; Davis, M.; Gumikiriza-Onoria, J.L.; Kinyanda, E.; Moffett, B.D.; van Heerden, A.; O’Mahen, H.; Craske, M.G.; et al. A narrative-gamified mental health app (Kuamsha) for adolescents in Uganda: Mixed methods feasibility and acceptability study. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e59381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.Z.; Koh, O.H.; Subramaniam, H.; Rosly, M.M.; Gill, J.S.; En, L.Y.; Sheng, Y.; Ip, J.W.J.; Shanmugam, H.; Ken, C.S.; et al. Exploring the implementation of gamification as a treatment modality for adults with depression in Malaysia. Medicina 2025, 61, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tera, T.; Kelvin, K.; Tobiloba, B. Evaluating gamified interventions in healthcare practice. PsyArXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo, V.D.; Prentice, M.; Lieder, F. Formative assessment of the insightapp: A gamified mobile application that helps people develop the (meta-) cognitive skills to cope with stressful situations and difficult emotions. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e44429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, M.; Chang, M.; Lin, F. Improving student mental health through health objectives in a mobile app. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnfield, M.; Rajesh, K.; Redd, C.B.; Gibson, S.; Gwillim, L.; Polkinghorne, S. Health-e minds: A participatory, personalised and gamified mHealth platform to support healthy living behaviours for people with mental illness. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.M.; Smit, J.H.; Fleming, T.; Riper, H. Serious games for mental health: Are they accessible, feasible, and effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Vantaraki, F.; Skoulidi, C.; Anastassopoulos, P.; Vantarakis, A. Gamified health promotion in schools: The integration of neuropsychological aspects and CBT-A systematic review. Medicina 2024, 60, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bantjes, J.; Hunt, X.; Cuijpers, P.; Kazdin, A.E.; Kennedy, C.J.; Luedtke, A.; Malenica, I.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zainal, N.H.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of remote digital gamified and group CBT skills training interventions for anxiety and depression among college students: Results of a three-arm randomised controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2024, 178, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T.C.; Kemp, A.H.; Edwards, D.J. Mixed-methods feasibility outcomes for a novel ACT-based video game ‘Acting Minds’ to support mental health. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e080972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbar, M.B.; Davison, R.; Ushaw, G. Virtual reality for cognitive behavioural therapy: A gamified approach and pilot study with university students. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Wageningen, The Netherlands, 9–11 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, N.A.; Shohieb, S.M.; Eladrosy, W.; Liu, S.; Nam, Y.; Abdelrazek, S. A gamified cognitive behavioural therapy for Arabs to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety: A case study research. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241263317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirivesmas, V.; Simatrang, S. Gamifying cognitive behavioural therapy techniques on smartphones for Bangkok’s millennials with depressive symptoms: Interdisciplinary game development. JMIR Serious Games 2023, 11, e41638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayal, S.; Rajagopal, K. Quiet pandemic amid COVID-19: A literature review on gamification for mental health. Asia Pac. J. Health Manag. 2024, 19, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, S.S.; Hammer, J.; Wehbe, R.R. “More than just a game, it’s an app that builds awareness around mental health”: Mental health stigma reduction using games for change. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 8, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingili, N.; Oyelere, S.S.; Nyström, M.B.T.; Anyshchenko, L. A systematic review on the efficacy of virtual reality and gamification interventions for managing anxiety and depression. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1239435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunwell, I. Conducting ethical research with a game-based intervention for groups at risk of social exclusion. In Games for Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eashwar, A.; Pricilla, S.E.; Aishwarya, P.A.P.; Baalann, K.P. Exploring gamification and serious games for mental health: A narrative review. Cureus 2024, 16, e74637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, E.; Anderson, A.C.; Hanegraaf, L.; Verdejo-García, A. Expanding gamified assessment of cognitive impulsivity through co-design with people with lived experience of eating disorders and mental ill-health: A mixed-methods study. JMIR Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S. Immersive and user-adaptive gamification in cognitive behavioural therapy for hypervigilance. TechRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano-Tejedor, C.; Cencerrado, A. Gamification for mental health and health psychology: Insights at the first quarter mark of the 21st century. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindigni, G. Exploring digital therapeutics: Game-based and eHealth interventions in mental health care: Potential, challenges, and policy implications. J. Biomed. Eng. Med. Imaging 2023, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category of Harm | Specific Harm | Causal Gamification Mechanic/Principle | Supporting Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological | Anxiety and Stress | Unattainable goals, high-frequency feedback, and constant performance pressure from features like leaderboards. | [25,26,27,29,30] |

| Autonomy | Cognitive Manipulation | Leveraging cognitive biases (e.g., loss aversion, scarcity) and opaque algorithms to influence user behaviour without their full awareness. | [14,30,31] |

| Privacy | Data Exploitation/Surveillance | Continuous tracking of sensitive personal and health data is required for personalisation and feedback loops. | [12] |

| Behavioural | Addiction/Compulsive Use | Use of variable reward schedules and compelling feedback loops designed to maximise time-on-app rather than therapeutic benefit. | [15] |

| Social | Negative Social Comparison | Public leaderboards and competitive features that rank users against one another can potentially exacerbate feelings of inadequacy. | [13] |

| AI Function | Example Application | Potential Benefit (to Efficacy) | Potential Risk (Ethical Concern) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personalisation/Adaptation | Dynamically adjusting the complexity of CBT exercises based on user performance; recommending meditations based on mood logs. | Increases therapeutic relevance and prevents user boredom or frustration, potentially closing the Engagement–Efficacy gap [32,33,34,35]. | Requires invasive data collection; risk of algorithmic bias; potential for hyper-personalised manipulation [41,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. |

| Conversational Agents (Chatbots) | Woebot or Wysa provides CBT through guided conversations and offers 24/7 crisis support. | Increases accessibility of care, reduces stigma, and provides continuous support [47]. | Lack of genuine empathy; risk of providing inappropriate advice in a crisis; potential for emotional dependency [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. |

| Player and Behavioural Analytics | Identifying which game mechanics lead to the highest user retention and promoting them within the app. | Can improve the overall user experience and increase long-term engagement [32,33,34,35]. | The optimisation goal (engagement) may conflict with the therapeutic goal, leading to the creation of addictive or compulsive loops. |

| Early Detection and Screening | Analysing speech patterns for signs of depression or decision-making patterns in a game to screen for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). | Enables early detection and intervention; provides objective data to supplement clinical assessment [41,42,43,44]. | Risk of misdiagnosis and stigmatisation due to algorithmic bias; significant data privacy concerns [55,56]. |

| HCI Interaction Mode | Example Design Choice | Potential Positive Mediation (Supporting Efficacy/Ethics) | Potential Negative Consequence (Prioritising Engagement) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-to-Data | Mood tracking with reflective journaling prompts vs. simple emoji logging. | Encourages deeper therapeutic engagement and self-awareness. | Simplistic logging is faster and easier, boosting “app engagement” but offering little therapeutic depth. |

| Human-to-Human | Moderated peer-support forum. | Fosters a sense of relatedness and community, supporting long-term well-being. | It can be less immediately “engaging” than a competitive feature. |

| Human-to-Human | Competitive Leaderboard. | It can motivate some users through social competition. | Induces anxiety, negative social comparison, and distracts from personal therapeutic goals. |

| Human-to-AI | Empathetic chatbot with transparent, explainable logic (XAI). | Builds trust and a strong digital therapeutic alliance, enhancing efficacy. | A purely engagement-optimised chatbot might use manipulative language or hide its logic to keep the user talking. |

| Human-to-Algorithm | Skill-based progression system that unlocks content based on mastery. | Supports competence and ensures the user is ready for the following therapeutic step. | A time-based or point-based system is easier to implement and can drive daily logins, but may not align with therapeutic progress. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ngabo-Woods, H.; Dunai, L.; Verdú, I.S.; Tîrșu, V. Gamification in Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review of the Engagement–Efficacy–Ethics Trilemma. Information 2026, 17, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020168

Ngabo-Woods H, Dunai L, Verdú IS, Tîrșu V. Gamification in Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review of the Engagement–Efficacy–Ethics Trilemma. Information. 2026; 17(2):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020168

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgabo-Woods, Harold, Larisa Dunai, Isabel Seguí Verdú, and Valentina Tîrșu. 2026. "Gamification in Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review of the Engagement–Efficacy–Ethics Trilemma" Information 17, no. 2: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020168

APA StyleNgabo-Woods, H., Dunai, L., Verdú, I. S., & Tîrșu, V. (2026). Gamification in Digital Mental Health Interventions: A Systematic Review of the Engagement–Efficacy–Ethics Trilemma. Information, 17(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17020168