2. Literature Review

This paper [

12] is a field-defining

introductory review rather than an experiment; accordingly, it reports concrete framework results instead of numeric model accuracies. It formalizes SHM as a four-step statistical pattern recognition paradigm featuring operational evaluation, data acquisition/normalization/cleansing, feature extraction/condensation, and statistical model development—explicitly stating that few studies cover all steps end to end. It operationalizes damage diagnosis into five escalating questions (existence, location, type, extent, prognosis), highlighting how unsupervised learning vs. supervised learning map to these levels and the safety implications of false positives/negatives. As real outcomes, the paper documents where SHM has demonstrably matured rotating machinery condition monitoring—citing decades of practice enabled by stable operating conditions, known damage locations, rich damaged-state data, and clear economic payoffs; in contrast, global SHM for large civil/aero systems remains largely pre-deployment with few transitions to practice outside machinery CM. It enumerates specific technical challenges now driving research—optimal sensor number/location, features sensitive to small damage, discrimination of damage vs. environmental variability, robust statistical discrimination, and comparative studies on common datasets—thereby setting measurable agendas rather than reporting accuracy tables. It quantifies the field’s momentum by noting a

rapid increase in publications over the preceding decade, motivating the theme issue and multi-disciplinary integration. While the review codifies SHM’s framework and challenges, it does not realize a BIM-coupled, digital-twin–ready pipeline that jointly predicts façade mechanical performance and lifecycle (AI–LCA) with feature attribution and deployment metrics—capabilities delivered by our system-of-systems decision support framework.

Pawlak’s doctoral thesis [

13] develops bio-based PLA/MLO composites reinforced with sheep-wool fibers (with/without silane or plasma treatments) and complements lab characterization with ML property prediction. The objective is to quantify how fiber concentration and surface treatment affect mechanics/thermal behavior and to build predictive models for design. The work executes tensile/flexural, impact, DSC/TGA, SEM, and aging studies; then, it trains regressors (decision forest, boosted trees, Poisson, linear) for tensile/flexural properties. Key results: TVS-treated wool markedly improves ductility, at 1 phr wool, elongation at break rises by ∼60% vs. untreated; at 5 phr by ∼40% (best sets: PLA/MLO-1Wool-1TVS, -2.5TVS; PLA/MLO-5Wool-2.5TVS); Young’s modulus is generally maintained with a significant increase at 2.5 phr TVS and comparable levels even at 10 phr wool; toughness improves with wool, and further with silane treatment; thermal stability shows single-step degradation with

°C (PLA/MLO), and DSC indicates treatment-dependent shifts in

and crystallinity (

°C for PLA;

°C,

for PLA_M_1WP); (v) ML models achieve strong accuracy for flexural strength/modulus (RSE

for decision forest; MAE

–

MPa across models; linear model best for modulus with MAE

MPa, RMSE

MPa). The thesis optimizes bio-composite processing and ML property prediction but does not realize a BIM-integrated, digital-twin–ready AI-LCA pipeline that jointly predicts façade-level mechanical performance and lifecycle indicators with feature attribution and deployment metrics—capabilities our framework delivers.

Xia et al. [

14] propose a

probabilistic sustainability design for concrete components under climate change that links time-variant structural reliability with lifecycle global warming potential (GWP) via a conditional “sustainable probability.” The research problem is that conventional reliability and LCA are treated separately, ignoring their interaction and the reusability of components. The paper defines sustainability as

; models resistance degradation with a climate-aware deterministic function and a stochastic

gamma-process ; introduces a resistance-based environmental impact

allocation rule for component reuse; and performs Monte Carlo simulation (up to

degradation curves) to compute durability life

, reliability, and sustainable probability. The results (numerical example) show large performance gaps across strategies:

conventional non-reusable design yields

sustainability,

recycling ,

reuse (first life) and

(second 50-year life), and

reuse + recycling ; simplifying assumptions (deterministic degradation or stationary climate) overestimate sustainability to

and

, respectively. While rigorous on reliability–LCA coupling and reuse allocation, the framework does not provide a BIM-integrated, AI-driven pipeline that

jointly predicts façade mechanical performance and environmental indicators, supports feature attribution for design trade-offs, or reports deployment metrics—capabilities delivered by our BIM-coupled AI-LCA decision support system.

Puttamanjaiah et al. [

15] propose a BIM-centric, data-driven decision support system (DDSS) for sustainable building design that transforms disparate project/operational datasets into actionable knowledge. The study’s objective is to overcome rule-of-thumb decision making by cataloging building data types (semantic BIM, geometric/IFC, simulation, and BMS sensor streams), outlining a KDD pipeline (selection, preprocessing, transformation, mining, interpretation), and integrating results through a

semantic integration layer within a Common Data Environment (CDE). The paper synthesizes BIM/CDE practice and knowledge discovery to define a system architecture that links heterogeneous repositories and enables three complementary analytics modes: direct semantic queries over linked data, geometric feature matching for shape/topology, and data mining (including temporal motif/association discovery) for operational streams. Findings are conceptual and architectural: a web-based, graph-oriented CDE with a thin semantic layer can preserve native numeric stores while supporting customized, goal-oriented retrieval; the approach identifies critical early-design dependencies and clarifies how mined patterns can re-enter design tools as decision aids; key challenges include implementing the semantic layer without constraining downstream analytics and validating matching strategies between “past and present” cases. The framework does not deliver a BIM-coupled,

AI–LCA pipeline that jointly predicts façade

mechanical performance and

lifecycle indicators with feature attribution and deployment metrics for digital-twin use; our study operationalizes precisely this dual-objective, system-of-systems decision support.

In another paper, Petrova et al. [

9] target MitM detection in SCADA–IoT by training ML classifiers on a curated subset of CICIoT2023 (82,272 benign and 10,977 MITM-ArpSpoofing samples) to deliver deployable accuracy for critical infrastructure. The objective is to replace brittle, signature-based defenses with data-driven models tuned for SCADA traffic characteristics. The pipeline applies rigorous cleaning (removing NaN/

∞), min–max normalization, label binarization, SMOTE balancing, and a wrapper feature-selection scheme before fitting JRip, Random Forest (RF), Classification-via-Regression (CvR), and J48; an 80/20 train–test split and standard metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1) are used for evaluation. Results show consistently strong performance with RF the best overall:

RF Accuracy = 98.22%, Precision/Recall/F1

;

CvR (0.980/0.980/0.980);

J48 = 97.85% (0.978/0.979/0.978);

JRip (0.976/0.976/0.975). The wrapper process reduces dimensionality while retaining accuracy, indicating a compact, SCADA-relevant feature set. While effective for cybersecurity telemetry, this study focuses on network-traffic classification and does not offer a BIM-integrated, digital-twin-ready

AI–LCA decision pipeline that jointly predicts façade mechanical performance and lifecycle indicators with feature attribution and deployability reporting—capabilities delivered by our system-of-systems framework.

This work [

16] proposes an Edge-based Hybrid Intrusion Detection Framework (EHIDF) for mobile edge computing, aiming to detect unknown attacks with low false-alarm rates in resource-constrained environments. The research problem targets the poor detection of novel intrusions by conventional firewalls and standard ML IDSs in edge networks. EHIDF integrates multiple detection modules (a signature-driven module, an anomaly-driven module, and a fusion layer) and evaluates them against prior baselines, reporting per-module and overall metrics and analyzing security via a game-theoretic model. In comparative experiments, the framework achieves an overall accuracy of 90.25% with an FAR of 1.1%, improving accuracy by up to 10.78% and reducing the FAR by up to 93% relative to prior works; the constituent modules attain 86.04% accuracy (FAR 8.4%) and 86.94% accuracy (FAR 2.1%) for SDM and ADM, respectively. The authors also note future dataset extensions (UNB ISCX 2012, IDEVAL). Despite gains, the design is limited to 15 features and assumes potential feature independence—constraints that hinder robustness and explainability—leaving room for a physics/semantics-aware, dynamically adaptive pipeline with optimized feature selection and deployment metrics, which our approach provides.

Papalambros [

17] surveys and experimentally benchmarks adaptive ML algorithms for high-dimensional data (genomics, healthcare, finance), contrasting deep learning, ensemble learning, autoencoders, and reinforcement learning. The problem addressed is balancing accuracy, scalability, and computational efficiency under the “curse of dimensionality". The authors preprocessed multi-domain datasets, performed 80/20 splits with cross-validation and hyperparameter tuning, and compared families of algorithms on accuracy, training time, GPU hours, and a 1–5 scalability score. Deep learning achieved the highest accuracy (92.3%) with the best but required 12 h of training and 45 GPU hours; ensembles reached 90.1% in 6.5 h/25 GPU hours; reinforcement learning attained 88.9% in 9 h/30 GPU hours (scalability 3); autoencoders delivered 87.5% with the shortest time (3.5 h) and 15 GPU hours (scalability 4). The study concludes that method choice hinges on resource constraints and target accuracy. While providing a clear accuracy–efficiency front for generic high-dimensional tasks, the study does not implement a BIM-coupled, digital-twin-ready

AI–LCA pipeline that jointly predicts façade mechanical performance and lifecycle indicators with feature attribution and deployment metrics—capabilities our system-of-systems framework contributes.

Wilson and Anwar’s review [

3] surveys the role of natural fibers and bio-based materials in the building sector from a sustainable-development perspective, tracing historical practices to contemporary housing and documenting adoption barriers and enablers. The objective is to consolidate evidence on performance, durability, cost, regulatory standardization, and cultural acceptance to clarify when and how natural materials can substitute conventional ones. The research problem addressed is the fragmented, non-standardized knowledge base that hinders the wide deployment of straw, bamboo, hemp, and wool fiber solutions in modern construction. The paper conducts a structured narrative synthesis with comparative tables of traditional vs. modern systems (materials, geographic range, advantages/disadvantages) and curated case illustrations. The results emphasize low embodied-impact profiles and strong insulation/weight advantages for natural materials alongside durability concerns (moisture, pests), code/standard gaps, and project-delivery risks tied to labor-intensive processing and missing specifications; it also highlights the rising influence of prefabrication/modular methods and growing ecological demand in Europe, Asia, and South America. Despite mapping the landscape, the review does not deliver a BIM-integrated, physics-aware AI decision framework that quantitatively links façade-level mechanical performance with lifecycle indicators (AI–LCA), provides feature attribution, and reports deployment metrics—capabilities our system-of-systems pipeline supplies.

Gökçe and Gökçe [

1] present a multidimensional energy monitoring, analysis, and optimization system that integrates ubiquitous sensing (wired BMS + wireless WSAN), BIM/IFC-driven context, and a Data Warehouse (ODS/Fact/Dimensions/OLAP cubes) to support building energy decision making. The study targets the lack of holistic, interoperable toolchains in BEMS—whose predefined strategies and non-learning control can cost 10–15% efficiency—and the difficulty of unifying BIM tools with operational data streams. The authors define a four-step process (data collection; multidimensional analysis with DW/OLAP; user awareness via role-specific GUIs; optimization), implement an SOA-based ETL to fuse BMS CSV logs and WSAN feeds into a star schema (Time, Location, Organization, Sensing Device, HVAC), and expose aggregated indicators for control scenarios (heating, lighting, real-time consumption). The results are validated in the 4500 m

2 ERI building (UCC) equipped with 180 wired sensors/meters and ∼80 wireless nodes: the ODS–ETL–DW pipeline functioned end-to-end, GUIs supported stakeholders (owner, FM, occupant, technician), and continuous analysis led to actionable opportunities for energy savings. The OLAP examples illustrate roll-up/cube queries and aggregated consumption (a 2D cube totaling 14,228 units across spaces/years). While the system achieves BIM–sensors–DW integration for monitoring and control, it does not deliver a BIM-coupled, digital-twin–ready

AI–LCA pipeline that jointly predicts façade mechanical performance and lifecycle indicators, provides feature attribution for design trade-offs, or reports deployment metrics (latency/memory)—capabilities contributed by our AI-enabled system-of-systems framework.

Kim et al. [

18] develop bio-based PLA/MLO composites reinforced with sheep-wool fibers (with/without silane or plasma treatments) and complement laboratory characterization with machine learning (ML) property prediction. The objective is to quantify how fiber concentration and surface treatment affect mechanical/thermal behavior and to build predictive models for design. They execute tensile/flexural, impact, DSC/TGA, SEM, and aging studies; then, they train regressors (decision forest, boosted trees, Poisson, linear) for tensile/flexural properties. TVS-treated wool markedly improves ductility at 1 phr wool, elongation at break rises by ∼

vs. untreated; at 5 phr by ∼

(best sets: PLA/MLO-1Wool-1TVS, -2.5TVS; PLA/MLO-5Wool-2.5TVS); Young’s modulus is generally maintained, with a significant increase at 2.5 phr TVS and comparable levels even at 10 phr wool; toughness improves with wool and further with silane treatment; thermal stability shows single-step degradation with

°C (PLA/MLO), and DSC indicates treatment-dependent shifts in

and crystallinity (

°C for PLA;

°C,

for PLA_M_1WP). ML models achieve strong accuracy for flexural strength/modulus (

for decision forest;

–

MPa across models; the linear model has the best modulus results with

MPa,

MPa). The thesis optimizes bio-composite processing and ML property prediction but does not realize a BIM-integrated, digital-twin-ready AI–LCA pipeline that jointly predicts façade-level mechanical performance and lifecycle indicators with feature attribution and deployment metrics—capabilities our framework delivers.

3. Methodology

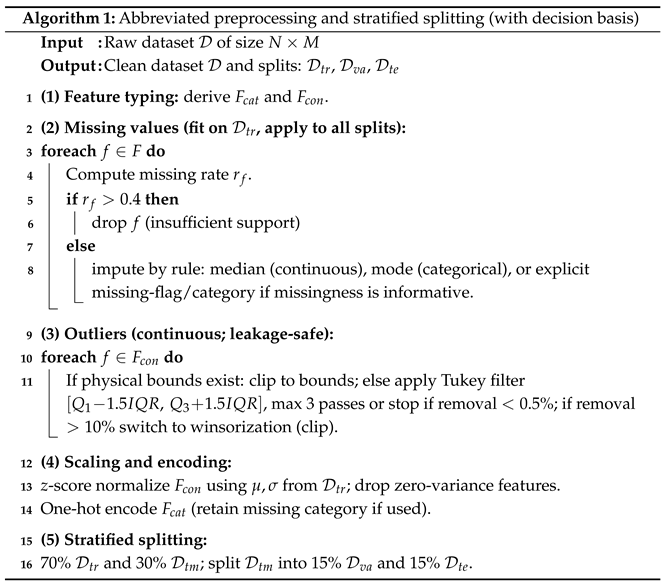

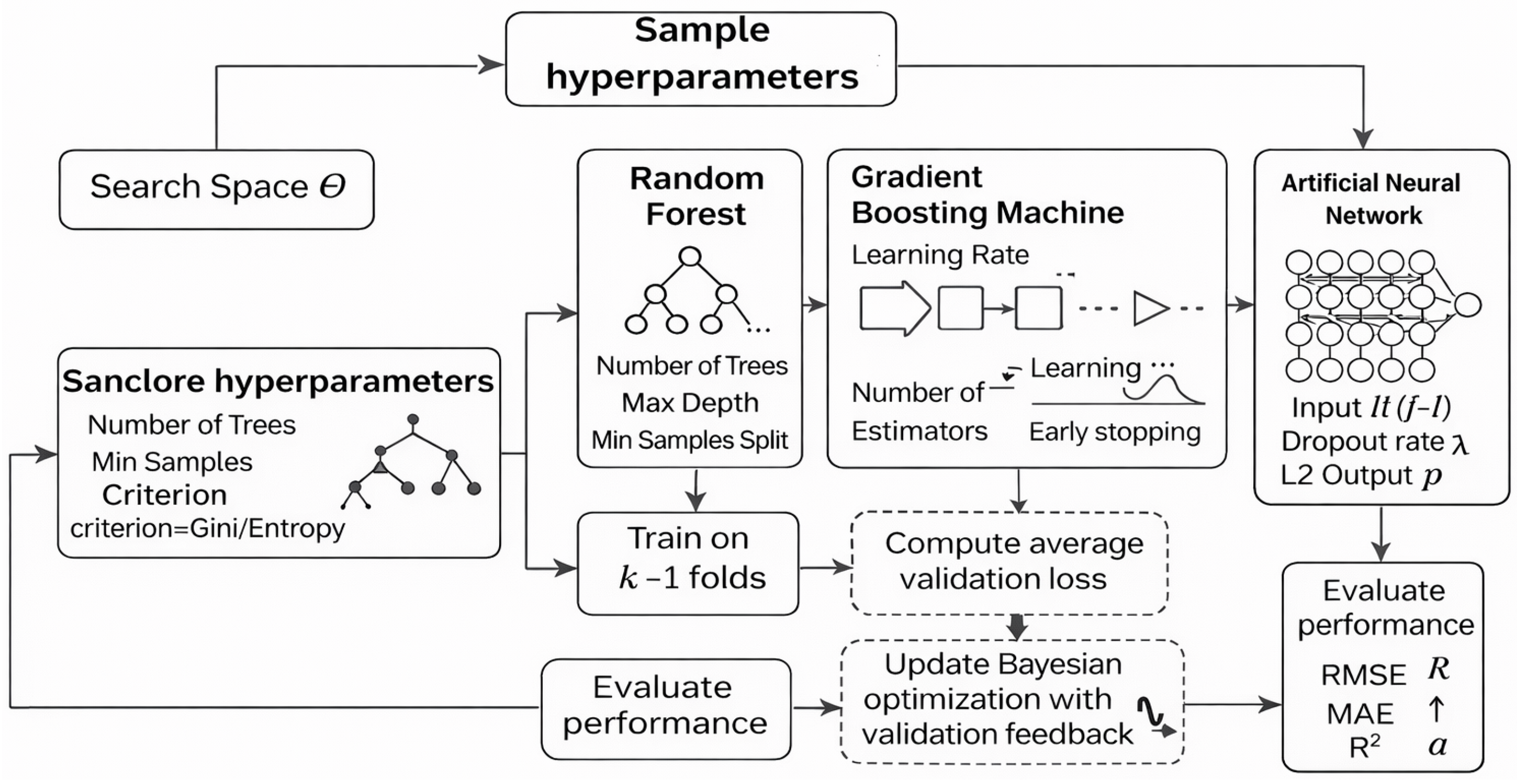

The methodology adopted in this study integrates advanced machine learning with a lifecycle assessment (LCA) to enable a dual prediction of both the mechanical properties and environmental impacts of construction materials. The process, illustrated in

Figure 1, begins with dataset integration from multiple sources, including Ecoinvent, BuildingsBench, and experimental records, which is followed by systematic preprocessing steps to ensure data reliability. Data cleaning addresses duplicates and missing entries, while imputation or row/column removal strategies handle incomplete values. These preprocessed datasets are then normalized and encoded, ensuring compatibility with machine learning models [

19]. After a stratified train-validation-test split, the AI-LCA framework consisting of Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machines, and Artificial Neural Networks performed dual prediction across mechanical and environmental dimensions. Model training employed 10-fold cross-validation and Bayesian hyperparameter tuning, while early stopping mechanisms were guided by validation loss to prevent overfitting. Performance was evaluated using conventional ML metrics-accuracy, RMSE, and

-alongside LCA metrics such as CO

2 footprint and energy use. Finally, resilience testing against replay, spoofing, and adversarial noise and deployment feasibility analysis ensured robustness and real-world applicability. Thus, these figure represent a structured, multi-stage pipeline that balances predictive accuracy, environmental accountability, and system resilience [

20].

3.2. Data Preprocessing

The raw datasets obtained for this study integrate structural, mechanical, and environmental parameters relevant to civil engineering applications. Attributes include material properties, compressive strength, elasticity modulus, structural geometry, load conditions, and performance indicators. However, raw experimental and simulated data often contain inconsistencies such as missing entries, varying scales, and outliers, which must be carefully addressed before modeling. Thus, a systematic preprocessing pipeline is implemented to ensure data quality, homogeneity, and suitability for artificial intelligence applications in structural engineering [

21].

The first step involves data cleaning and imputation. Missing numerical values such as strength or load capacities were imputed using median substitution to reduce sensitivity to extreme values, while categorical attributes, such as construction type and failure mode, are imputed using a statistical mode [

22]. Outliers, such as physically impossible negative material properties or extremely high load factors, were detected using an interquartile range (IQR method) and subsequently removed. This ensured that these datasets remained physically realistic and consistent with engineering logic [

23].

After cleaning, all continuous features were normalized with z-score normalization [

7]. This standardization guarantees that predictors such as compressive strength and stiffness had non-zero means and variance equal to one, eliminating the dominance of large-magnitude variables in these learning processes. For category attributes such as building type, one-hot encoding was applied to transform them into binary indicator vectors and make them compatible with machine learning [

24]. This representation improves interpretability and enables incorporation into regression, classification, and deep learning models [

9].

These datasets are randomly divided into three subsets (training 70%, validation 15%, testing 15%). Stratification was used to retain a distribution of structural types and rare cases between sets, ensuring unbiased testing. These preprocessing pipelines have led to a balanced, normalized and machine-learning-friendly dataset that offers an underpinning for predictive analytics and optimization in structural civil engineering.

Table 4 summarizes the preprocessing stages. Each step plays a critical role in transforming heterogeneous raw structural data into a standardized, balanced, and machine-learning-compatible format. Together, these measures reduce noise, enhance comparability, and strengthen the reliability of subsequent AI-driven analysis.

The proposed algorithm (Algorithm 1) provides a programmable and systematic pipeline for preprocessing the raw dataset before model training. It begins by identifying categorical and continuous feature groups, which is followed by computing missing value rates. Features with excessive missingness greater than 40% are flagged for removal, while others were imputed using median, mode, or constant strategies via a switch–case structure. After imputation, these algorithms are checked for whether any features needed to be dropped, and the feature sets were refreshed accordingly. Outlier detection was performed using interquartile ranges (IQRs), iteratively filtering extreme values for up to three passes until convergence. Continuous features are normalized through z-score standardization, and categorical variables are encoded using one-hot representation to enable machine learning compatibility. Finally, boundary clipping and binary conversions were applied where relevant, and the cleaned dataset was stratified into training, validation, and testing splits. By integrating modular programming constructs such as loops, while-statements, switch cases, and conditional branching, this algorithm achieves both clarity and flexibility, allowing it to easily be adapted for diverse datasets while ensuring data consistency and quality.

![Information 17 00126 i001 Information 17 00126 i001]()

3.3. AI–Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) Framework

These proposed frameworks are an advancement of traditional process-based LCA by utilizing AI methods to account for intricate interrelations between material design parameters and environmental consequences [

25]. In traditional LCA, valuation conventions include deterministic inventory models and fixed impact pathways, which cannot account for nonlinear and hidden relationships in complex civil engineering materials. In our work, baseline process-based LCA is established (shown as squared blocks) that supplies these reference environmental impact categories (global warming potential (GWP), embodied energy and water footprint [

26]).

Machine learning models such as GBM and ANN are used to improve predictive performance and reduce computational burden. RF and GBM account for the nonlinear nature of a response, with the possibility of interpreting feature importance, while ANNs are based on representation learning, which can flexibly model complex relations between mechanical and environmental properties [

27]. They were trained in a structured database of structural concrete composites with input parameters, such as fiber content, curing conditions, mix proportions and façade parameters. These products are twin objectives: (1) mechanical properties (for example, compressive strength) and (2) environmental burdens (for example, emissions of CO

2 [

28]).

The fusion of AI with LCA results in a multi-output predictive framework such that the models can predict mechanical strength and environmental pros and cons at the same time [

29]. Such workflows are then changed from the usual sequential one of “design → testing → evaluation” into a predictive loop, saving time and resources. The use of ensemble and deep learning models allows this apparatus to be highly accurate as well as sensitive to engineering performance and sustainability constraints [

30]. Additionally, feature importance analysis based on AI throws lights on these major design drivers and allows engineers to prioritize sustainable parameters without compromising mechanical viability [

31].

Feature importance analysis indicates that the fiber dosage, curing time, and water/cement ratio are significant parameters for measuring environmental impact [

32]. For instance, the tensile strength was significantly increased by increasing the fiber content, while the embodied carbon also was increased, indicating a sustainability–performance trade-off. Similarly, curing regimes play a dual role: extended curing improves durability but also increased energy use [

33]. These insights demonstrate the potential of AI-LCA not only as a predictive tool but also as a decision-support system, guiding engineers toward optimized trade-offs between mechanical performance and environmental sustainability [

34].

Table 5 compares the performances of AI models within an LCA framework. RF provides interpretability through feature importance analysis, making it suitable for identifying key environmental drivers. GBM demonstrates superior predictive accuracy, offering a strong balance between performance and efficiency. ANNs were most effective in capturing complex nonlinear interactions but required larger datasets to generalize effectively. The hybrid use of these models ensures robust predictions while supporting interpretability and actionable sustainability insights.

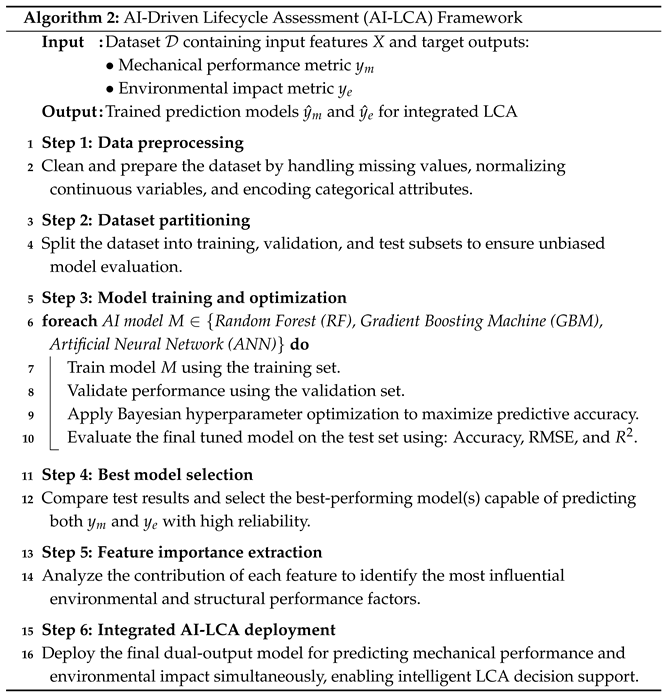

Algorithm 2 presents an end-to-end AI-driven lifecycle assessment (AI-LCA) pipeline that integrates structural performance intelligence with environmental sustainability modeling. Initially, these data preprocessing stages ensure analytical reliability by addressing missing values, resolving mixed feature types, and enforcing statistical normalization, thereby optimizing input representation for downstream learning. A stratified data partitioning strategy is then employed to avoid overfitting and preserve generalization capability. The core of this framework is systematically training multiple candidate regression models—including RF, GBM, and ANN—while Bayesian optimization intelligently explores these hyperparameter search spaces to enhance predictive fidelity. The subsequent model selection phase emphasizes multi-objective evaluation by jointly maximizing mechanical performance prediction accuracy and environmental impact estimation effectiveness, supporting a balanced material–design decision making trade-off. Feature attribution analysis further improves the interpretability by revealing which design variables drive both functional efficiency and sustainability behavior. Finally, these deployment components operationalize dual-output prediction, enabling real-time AI-assisted LCA guidance that supports environmentally informed structural engineering. Overall, the framework provides a robust, explainable, and implementable pathway for bridging data-driven structural design and green construction analytics.

![Information 17 00126 i002 Information 17 00126 i002]()

3.4. Model Training and Optimization

The training and optimization of predictive models for energy-efficient façade systems are carried out using a rigorous machine learning framework. To ensure unbiased evaluation, we employed a 10-fold cross-validation scheme, where the datasets are randomly partitioned into ten equal subsets. In each iteration, nine folds were used for training, while one fold was reserved for validation. This rotation process reduces the risk of overfitting and provides a more reliable estimate of model generalization. A final performance metric was averaged across all folds to obtain a stable result.

Hyperparameter tuning was conducted using Bayesian optimization, which adaptively explores this parameter search space by balancing exploration and exploitation. Unlike a grid search or random search, Bayesian optimization uses prior evaluations to build a surrogate model of this objective function, accelerating convergence to near-optimal configurations. Through utilizing Random Forests and Gradient Boosting Machines, hyperparameters such as the maximum depth, number of estimators, and learning rate were tuned. By using Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), parameters such as the number of hidden layers, neurons per layer, activation functions, and dropout rate were optimized.

A mechanism of early stopping has been introduced in order to prevent overfitting, especially during the ANN learning process. Computational efficiency and overfitting were considered by early stopping when no improvement in the validation losses was detected for ten consecutive epochs. These criteria ensured that all of the models generalized well from training samples to unseen data rather than memorizing these training images. Furthermore, regularization methods including dropout and L2 weight decay were applied to improve robustness.

Comparisons were made with baseline regression models like linear regression and ridge regression in order to demonstrate the additional value offered by advanced AI approaches. The evaluation was based on performance measures such as the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Coefficient of Determination (

R2). A comparison of the results indicates that these AI-enhanced models were more effective in representing the nonlinearity and complex interrelations among building façade performance data.

where

denotes hyperparameters,

the search space, and

the validation loss at fold

i.

Table 6 summarizes the adopted training and optimization techniques. Each strategy was carefully integrated to ensure robustness, efficiency, and reliability in predictive modeling.

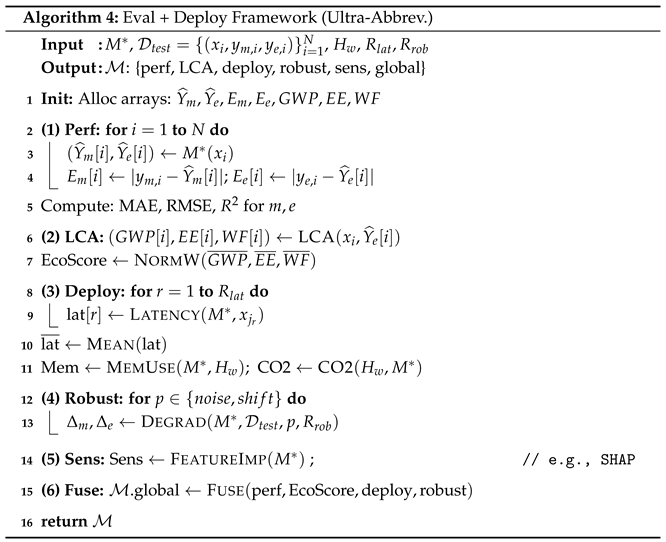

The model training and Bayesian optimization pipeline shown in Algorithm 3 present a systematic strategy for maximizing the predictive performance while maintaining generalization reliability across multiple learning paradigms. By introducing a 10-fold cross-validation structure at the outset, this framework ensures that each model underwent performance testing across diverse data partitions, minimizing bias and variance risks. This pipeline uniquely enhanced model development through Bayesian optimization, which efficiently navigates each algorithm’s hyperparameter search space using probabilistic inference rather than brute-force or grid-based exploration. This targeted search was strengthened by the integration of early stopping, preventing overfitting and unnecessary computation during training iterations. Performance evaluations were standardized across regression metrics such as RMSE, MAE, and , enabling a fair benchmarking of traditional tree-based models against deep learning architectures like ANN. Ultimately, this pipeline selected the model that delivers the highest average predictive accuracy across validation folds, ensuring robustness and reliability prior to deployment. This approach not only accelerates optimization convergence but also supports reproducibility and the high-confidence adoption of the best-performing model within a broader AI-LCA decision-support framework.

![Information 17 00126 i003 Information 17 00126 i003]()

Figure 2 illustrates the automated hyperparameter optimization pipeline employed in this study for training these three predictive models: Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machine, and Artificial Neural Network. The process began by defining a search space of candidate hyperparameters, which were iteratively sampled and used to configure each model. These models were then trained using the

folds of each dataset, and their performance was validated by computing the average validation loss. This validation feedback was then passed to the Bayesian optimization controller, which continuously refined a hyperparameter sampling strategy to prioritize more promising configurations. Upon the completion of optimization rounds, these trained models were evaluated using independent test data, where performance metrics including the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Coefficient of Determination (

were computed. The framework efficiently balanced exploration and exploitation to identify optimal hyperparameters while ensuring robust and accurate predictions of both structural and sustainability outcomes. All data preprocessing, machine learning modeling, and optimization procedures were implemented using a Python (version 3.10) computational environment. Lifecycle assessment (LCA) indicators were derived using EcoInvent-based environmental inventories under a clearly defined functional unit. The proposed framework is designed to cooperate with commercial BIM platforms through open interoperability standards. The building geometry, material quantities, and façade parameters were exported from BIM authoring tools (Autodesk Revit or Archicad) using IFC or gbXML formats and processed within the AI-LCA pipeline. The resulting performance indicators can be re-imported into the BIM environment via parameter mapping or API-based workflows (Revit API or Dynamo scripts), enabling seamless integration without proprietary software lock-in.

The selection of Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) was motivated by their complementary strengths for building reliable multi-output surrogate predictors on the heterogeneous, moderate-size tabular engineering datasets typical of BIM-LCA-materials integration. RF and GBM are strong baselines in civil structural informatics because they capture nonlinear interactions, handle mixed continuous-categorical inputs with minimal preprocessing, provide robust generalization through bagging–boosting, and offer practical interpretability via feature-importance analyses—capabilities that directly support our dual-prediction, decision-support objective. ANN was included as a flexible parametric learner to benchmark against a fundamentally different function-approximation paradigm and to ensure extensibility when larger datasets are available while still enabling fast batch inference for digital-twin use. In contrast, reinforcement learning is principally suited to sequential control with explicit states, actions, and rewards (Markov decision processes), which does not match our static, evaluative façade design setting. Bayesian networks require explicit conditional-independence structure assumptions and can become unwieldy for high-dimensional continuous multi-target regression. Therefore, the chosen model set represents a deliberate balance between accuracy, scalability, interpretability, and reproducibility, ensuring that improvements are attributable to the proposed BIM-coupled dual-prediction framework rather than to highly specialized algorithms.

3.6. Evaluation Metrics and Deployment

We evaluated the proposed framework from the perspectives of both predictive performance and real-world usability through a comprehensive collection of quantitative and qualitative measures. All computational analyses and machine learning-based surrogate modeling were performed in MATLAB R2023a (MathWorks), with BIM interoperability achieved via standardized data exchange (IFC and/or structured CSV/JSON schedules) from commercial BIM platforms, enabling bidirectional integration without reliance on proprietary plug-ins. The predictive performance of the models was assessed using traditional machine learning metrics such as Accuracy, Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (

) [

35]. These metrics provide strong indications of how well the models can predict key structural and durability responses with limited deviation from the ground-truth experimental or simulation-based benchmarks. RMSE and MAE penalize prediction errors (with RMSE being more sensitive to larger errors), while

quantifies the proportion of variance explained by the predictors.

Beyond prediction, lifecycle assessment (LCA)-relevant indicators were implemented to assess the sustainability effects of this design. Finally, GWP in CO2-eq, EE (in MJ) and WF (in m3) were added to the assessment pipeline. These indices guarantee that this highly effective structure design was not only mechanically efficient but environmentally friendly. By integrating predictive modeling with sustainability indicators, we were able to simultaneously maintain structural reliability and environmental responsibility in civil engineering.

Deployment feasibility was also evaluated to ensure the scalability of the approach in practice. Two primary deployment metrics were tracked: inference latency (in milliseconds) and memory footprint in MB. These metrics determine whether a proposed AI-enhanced system was integrated into real-time structural design workflows or digital twins without overwhelming computational resources. Low latency ensured interactive usability, while a modest memory footprint supported portability across engineering workstations and embedded decision-support platforms.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of predictions under variations in critical design parameters such as fiber type and curing regime. By systematically perturbing these inputs, this study examines the stability of both predictive and sustainability outcomes, highlighting which variables most strongly influence performance. This analysis not only validates the generalizability of the predictive framework but also provides practical insights for engineers in prioritizing design parameters for sustainable civil structures.

Table 7 highlights this integrated evaluation framework. Predictive metrics validate the accuracy and error margins, LCA indicators quantify the environmental sustainability, and deployment metrics ensure practical feasibility. Together, these measures demonstrates that the framework balances engineering accuracy, ecological responsibility, and computational efficiency.

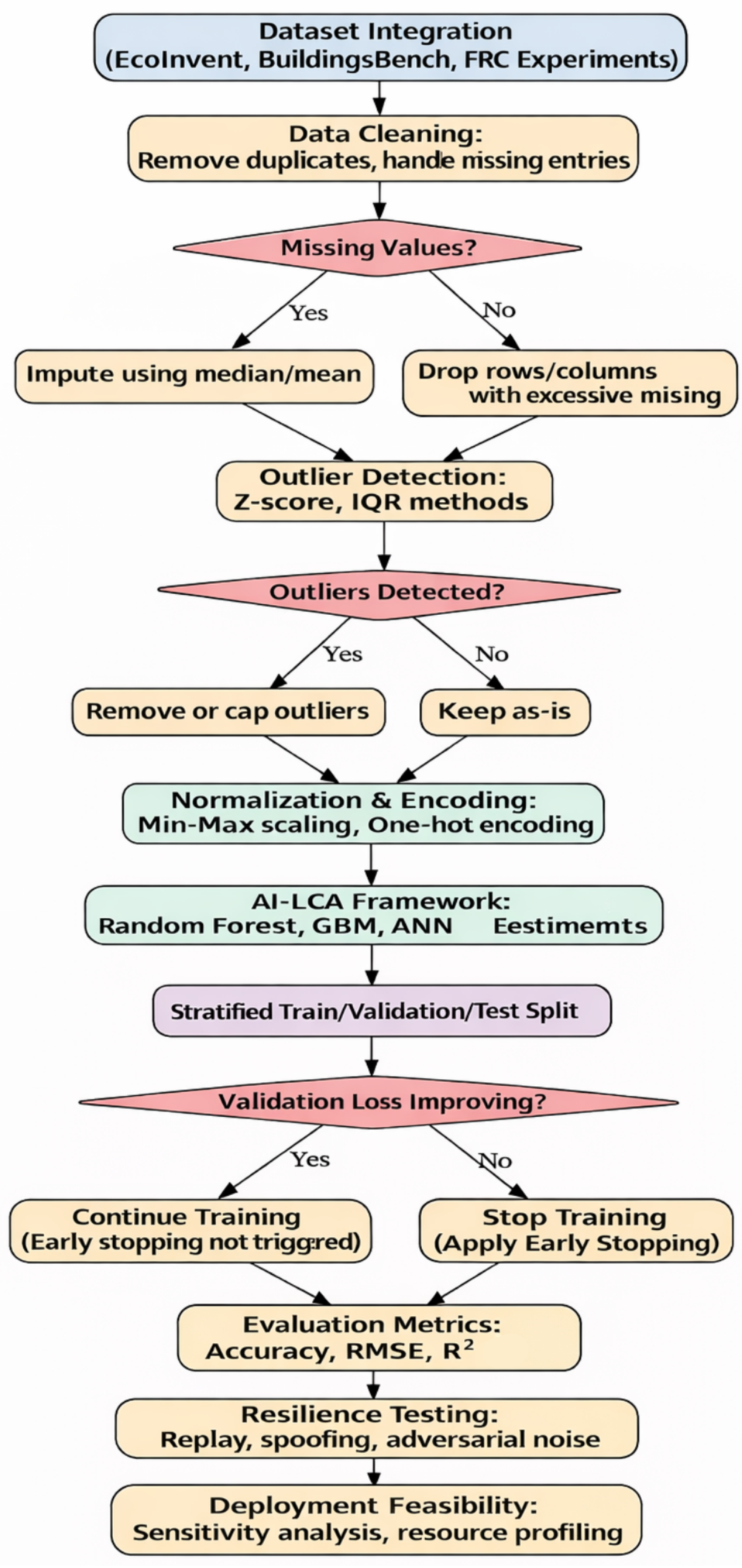

The evaluation and deployment framework summarized in Algorithm 4 provides this fully programmable, multi-objective pipeline that jointly assesses the predictive accuracy, sustainability, and operational feasibility of a proposed model. For each test sample —a composite mixture characterized by fiber type such as Hemp or Glass, fiber volume ratio such as , curing regime such as steam curing, and specimen age such as 28 days—these algorithms simultaneously predict the mechanical response, the compressive strength, and an environmental indicator, . These predictions are compared to ground-truth targets to compute sample-wise errors and aggregate metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and for both mechanical and environmental outputs, . In parallel, lifecycle assessment (LCA) indicators, including the Global Warming Potential (GWP), embodied energy (EE), and water footprint (WF), are evaluated and normalized into a composite EcoScore, enabling a fair comparison between greener alternatives, hemp–fiber mixes with lower GWP and EE and more carbon-intensive options, such as glass–fiber composites or synthetic fibers. This framework further profiles deployability on a target hardware platform , and an edge device such a Jetson Nano or Raspberry Pi, by measuring the inference latency, few milliseconds per sample, peak memory usage, and estimated emissions per prediction via an energy model. Robustness was examined by injecting controlled perturbations, additive Gaussian noise, slight shifts in the water–cement ratio, or modified curing conditions, quantifying performance degradation. Meanwhile, sensitivity analysis, via permutation importance or SHAP values, ranks the most influential input features—often revealing that parameters such as the water–cement ratio or fiber volume dominates the response. Finally, all of the partial scores—including the accuracy, EcoScore, deployability, robustness, and sensitivity-derived interpretability—were fused into a global evaluation index , providing concise yet comprehensive decision metrics for selecting composite designs that are structurally efficient, environmentally responsible, and computationally feasible for smart building applications.

![Information 17 00126 i004 Information 17 00126 i004]()

4. Discussion Results and Comparison

The results obtained from this proposed framework provide a comprehensive view of how artificial intelligence can be leveraged to balance structural performance, sustainability, and energy efficiency in fiber-reinforced façade composites. As summarized in

Table 9, the preprocessing pipeline successfully transforms these heterogeneous datasets into a structured, machine learning-ready format, ensuring both statistical rigor and engineering realism. Subsequent evaluations demonstrate that these stacked ensemble models achieve superior predictive accuracy compared to standalone learners, particularly in predicting compressive strength and Global Warming Potential (GWP). Moreover, these multi-objective optimization outcomes highlight clear trade-offs between mechanical strength and environmental performance across fiber types, while the sustainability gains quantified in

Table 9 confirm the practical value of AI-driven material design. These findings not only validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework but also position it as a decision-support tool for optimizing façade systems in next-generation smart buildings.

These preprocessing results in

Table 9 highlight the transformation of these heterogeneous datasets into structured, machine learning-ready form. Initially, this dataset combines multiple complementary sources—Ecoinvent, BuildingsBench, and experimental FRC data—totaling 15,732 records with 47 features, of which 15 were categorical. This integration ensures coverage across mechanical properties, environmental indicators, and energy-performance contexts but also introduces inconsistencies such as missing entries and heterogeneous data types. The challenge of harmonizing such diverse sources underscores the importance of this robust preprocessing pipeline, which maintains both physical realism and statistical integrity.

These missing-value imputation steps reduced the dataset size slightly to 14,926 records while preserving a number of features. The median and mode imputations provide a balance between robustness and interpretability, especially when handling skewed numerical attributes and categorical variables. This is important in order to avoid any loss of data without allowing missingness to bias subsequent analysis. The relatively small decrease in the number of records at this stage means that these imputation approaches were effective at maintaining information, highlighting the importance of treating incomplete experimental or simulation-based civil engineering data with care. Further outlier removal using the three-pass IQR technique whittled the data down to 13,587 records—an approximate reduction of 1.4% per pass. This filtering step effectively blocked out extreme values without losing too much data. Considering these physical limitations of civil engineering materials and performance specifications, it was necessary to eliminate such outliers in order to ensure this validity from an engineering point of view and prevent spurious effects in AI training. The decision to cap iterations at three passes ensures convergence without over-pruning, thereby preserving general trends while eliminating inconsistencies that could undermine predictive reliability.

Normalization and encoding expanded the feature space to 71 predictors, all of which were continuous, ensuring uniform scaling and full compatibility with AI models. The final stratified partition of 70/15/15 across the training, validation, and test sets preserved class balance, reducing the risk of bias in evaluation. This progression from raw integration to clean, balanced, and standardized subsets highlights the methodological rigor adopted in preparing these datasets. The preprocessing pipeline not only enhances model interpretability and accuracy but also demonstrates a reproducible framework that can be generalized for future applications in AI-driven civil engineering research.

The preprocessing pipeline implemented in this study demonstrates a robust strategy for transforming heterogeneous structural datasets into a machine-learning-ready format. As shown in

Table 10, the integration of Ecoinvent environmental indicators, NREL BuildingsBench operational energy data, and experimental fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) results created datasets that were rich but inherently inconsistent. By combining mechanical, environmental, and energy domains, these datasets introduce challenges in terms of missing entries, scale heterogeneity, and outliers. Addressing these issues through systematic preprocessing was essential in order to ensure that the subsequent AI-driven analysis is both reliable and interpretable.

The missing-value imputation stage plays a critical role in minimizing data loss while preserving valuable engineering information. Approximately 5% of the original records exhibit missing entries in either mechanical or environmental attributes. Instead of discarding these rows—which could under-represent certain fiber types or building-context configurations—we applied median imputation for continuous variables and mode imputation for categorical variables. This choice preserves physical interpretability while reducing the risk that extreme values disproportionately influence model learning. The resulting retention of nearly 95% of the data demonstrates the effectiveness of a simple, domain-aligned imputation in civil engineering datasets, where experimental and simulation records frequently contain gaps.

Outlier removal based on the interquartile range (IQR) further improved data credibility by removing physically implausible observations (negative strengths or unrealizable environmental values). After three iterative passes, approximately 9% of the dataset was removed, yielding 13,587 records. This reduction improves physical soundness without over-pruning variability, allowing convergence to a stable subset that remains representative of realistic structural and environmental regimes.

Feature engineering increased the predictor space to 71 normalized inputs after scaling and encoding, enabling a balanced characterization across mechanical, environmental, and categorical factors. Z-score normalization prevents high-magnitude variables (embodied energy) from dominating training, while the one-hot encoding of categorical descriptors (fiber type, building archetype) yields interpretable, model-ready inputs. We then performed a stratified 70/15/15 split for training/validation/test to ensure class balance for rare configurations (hemp composites or extreme climate cases), reducing the risk of biased evaluation.

The results presented in

Table 8 highlight the trade-offs between mechanical strength and environmental burdens across the investigated fiber-reinforced façade composites. Hemp fiber composites (P1) provide a balanced performance, achieving a compressive strength of 44.7 MPa while exhibiting the lowest global warming potential (GWP = 212 kg CO

2-eq/m

3) and energy demand (1910 MJ/m

3). In contrast, steel fiber composites (P4) deliver the highest mechanical strength (52.3 MPa) but at the expense of substantially higher embodied carbon (340 kg CO

2-eq/m

3) and energy intensity (2330 MJ/m

3). Overall, these results confirm the expected sustainability–performance trade-off: improving strength through higher-impact reinforcement options can increase lifecycle environmental burdens.

Clarification: In this study, GWP is reported as kg CO2-equivalent per functional unit (not unitless). The functional unit is defined as of façade composite; therefore, GWP is expressed as kg CO2-eq/m3 throughout the manuscript.

Glass and polypropylene (PP) fibers (P2 and P3) demonstrates intermediate behaviors with glass achieving slightly higher strength (46.9 MPa) but incurring a higher carbon footprint than hemp and PP. Polypropylene composites offer relatively lower strength (42.6 MPa) but remain environmentally competitive with hemp. This pattern suggests that non-metallic fibers (hemp, PP) may provide more sustainable options, whereas glass and steel, while structurally robust, impose heavier environmental costs. Importantly, hemp emerges as the most promising candidate for sustainable façade composites because it combines reasonable strength with reduced ecological burden.

A sensitivity analysis (

Table 11b) illustrates the influence of fiber type and curing regime on both mechanical and environmental outcomes. Under accelerated curing (7-day), strength values reached 85–90% of their 28-day baseline with a modest increase in GWP 1.5–2.1%. This finding emphasizes that while early strength development could be achieved, it comes at a cost of higher embodied energy and carbon, especially in steel- and glass-based composites. Conversely, hemp and PP fibers maintained lower environmental penalties during accelerated curing, which strengthens their case for sustainable design in time-sensitive construction projects.

These observations also highlight this dual role of fiber dosage and curing regime as critical decision parameters in façade design. While higher fiber contributions is desirable, their environmental penalties, particularly in glass and steel systems, demand careful considerations. These results suggest that hybrid optimization strategies, such as combining hemp or PP fibers with optimized curing practices, could unlock synergies that improve structural resilience without substantially increasing the ecological footprint.

This discussion confirms the value of a multi-objective, AI-assisted optimization framework. By quantifying trade-offs between strength and sustainability, this study provides actionable insights for structural engineers seeking to design next-generation façades. Hemp- and PP-based composites appear most promising for sustainable applications, while glass and steel composites might be reserved for projects requiring maximum strength at higher environmental cost. This balance of engineering performance and ecological responsibility illustrates the necessity of data-driven, holistic approaches in advancing sustainable smart building technologies.

The results presented in

Table 12 highlight the significant sustainability gains achieved by an AI-optimized composite system compared to the baseline. The reduction in Global Warming Potential (GWP) by 24.3% is particularly notable, as it directly translates into reduced carbon emissions associated with material production. This improvement is driven by the intelligent selection and proportioning of hemp fibers, which balances mechanical strength with sustainability performance. Similarly, the embodied energy decreased by 15.1%, and the water footprint fell by 14.1%, both of which illustrate the capacity of the proposed framework to optimize across multiple environmental impact categories simultaneously.

In addition to material-level sustainability, AI-driven optimization yields benefits at the operational building scale. By integrating an optimized façade composite into a BuildingsBench context, the framework reduced the building energy use intensity from 96.4 kWh/m2·yr to 85.0 kWh/m2·yr, corresponding to an 11.8% relative gain. This result demonstrates that sustainable materials do not merely reduce embodied impacts but also improve the thermal performance and operational energy efficiency, thereby contributing to long-term carbon neutrality goals in a built environment.

Equally important are the deployment metrics, which ensure that these proposed frameworks are practical for real-world applications. Among the models tested, Random Forest achieved the lowest latency (4.1 ms and smallest memory footprint (42 MB), making it highly suitable for lightweight deployment in edge computing environments. Gradient boosting delivered a reasonable trade-off between speed and accuracy, while Artificial Neural Networks require higher memory and latency due to their complexity. The stacked ensemble achieved the best predictive robustness but incurred the highest computational cost (18.5 ms latency, 120 MB memory), making it more appropriate for offline design optimization rather than real-time decision making.

These results also underscore the critical trade-off among interpretability, efficiency, and predictive performance. Random Forests provide interpretability and efficiency but lower predictive depth, while this ensemble approach offers superior accuracy at the expense of resource efficiency. This trade-off suggests that deployment scenarios must be carefully matched to computational constraints—lightweight models for on-site applications and ensembles for research, design offices, or digital twin simulations.

These findings demonstrate that integrating AI into composite façade optimization provides a holistic advantage: reduced environmental burdens, enhanced building energy performance, and feasible deployment across diverse platforms. By explicitly quantifying sustainability gains and computational requirements, this study bridges the gap between theoretical advances in AI-driven materials optimization and their practical, scalable application in civil engineering and sustainable building design.

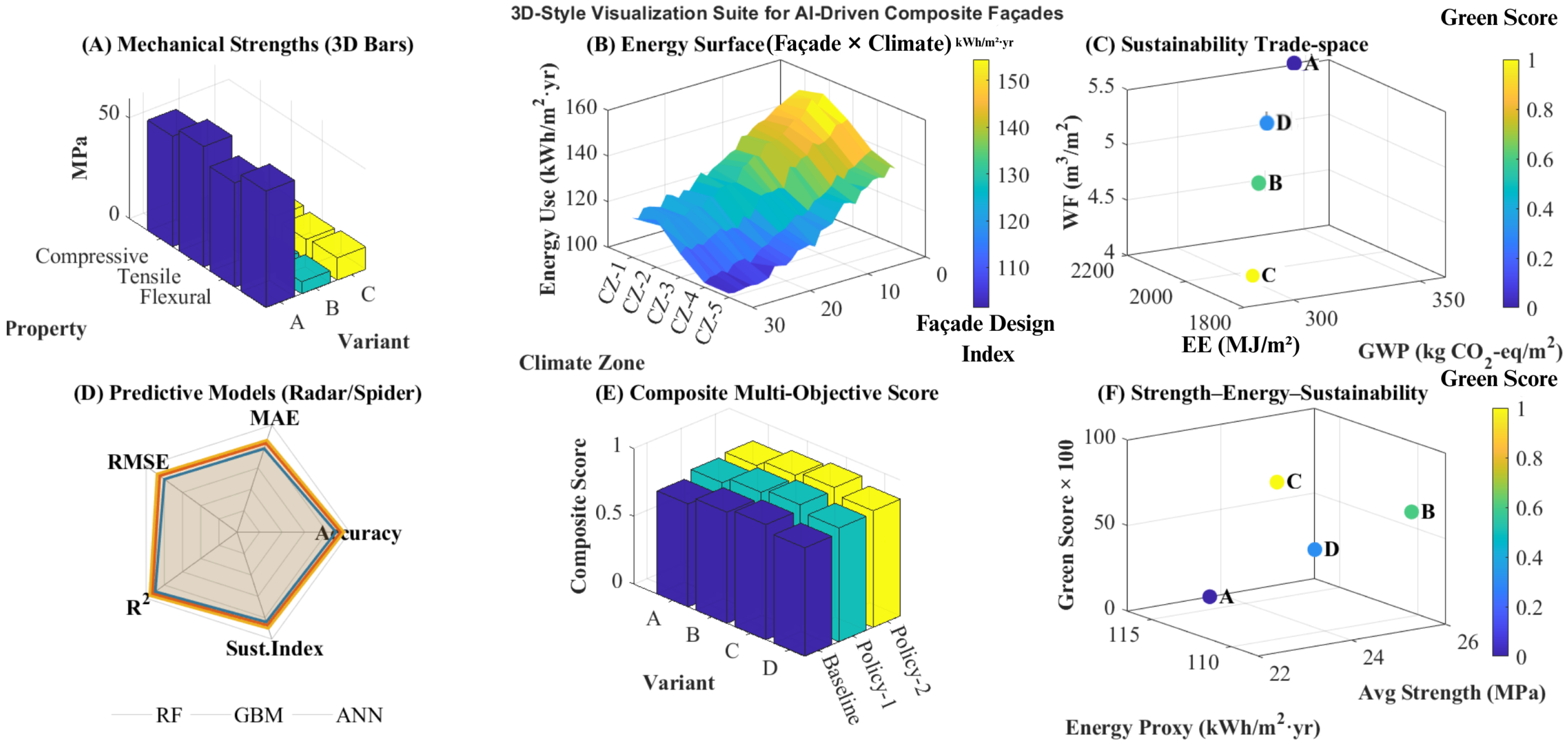

Figure 4 presents a comprehensive visualization of the multidimensional analysis conducted in this study. In subplot (A), a 3D bar chart illustrates the variation in mechanical strengths—compressive, tensile, and flexural—across material variants A–C. The results show that Variant A consistently delivers superior compressive and tensile strengths compared to other variants, confirming its structural robustness. However, they also highlight the inherent trade-offs, as the structural advantage of Variant A may come at the expense of sustainability, while these weaker variants exhibit reduced structural performance but could potentially align better with ecological goals.

In subplot (B), the energy surfaces reveal how façade design indices interact with climatic conditions to influence annual energy consumption. The energy demand declines as the façade optimization increases, particularly in moderate climates (CZ-2 to CZ-4). Conversely, unoptimized designs in harsher zones result in significantly higher energy use, emphasizing the necessity of tailoring façade designs to climatic contexts. This demonstrates that façade design decisions have a direct impact not only on structural efficiency but also on long-term operational energy performance.

Subplots (C) and (E) together depict the sustainability trade-offs and composite scores. The 3D scatter in subplot (C) highlights the environmental burden across Global Warming Potential (GWP), embodied energy (EE), and water footprint (WF). Here, Variant D shows strong ecological performance but at the cost of reduced strength, while Variant A sits at the opposite end with strong mechanical properties but higher environmental costs. A composite score analysis in subplot (E) integrates these diverse criteria under baseline and policy scenarios, revealing that balanced optimization strategies can align structural safety with sustainability. These underscores the importance of AI-driven frameworks in reconciling conflicting objectives.

Subplots (D) and (F) illustrate model evaluation and integrated performance insights. A radar chart in subplot D shows that ANNs achieve the best predictive outcomes across most metrics, outperforming RF and GBM in capturing nonlinear dependencies. Subplot (F) offers a holistic integration of strength, energy, and sustainability outcomes, where Variants B and C emerge as balanced solutions, achieving moderate mechanical strength and energy efficiency while maintaining acceptable sustainability scores. Together, these visualizations confirm that AI-driven optimization enables the identification of façade systems that achieve structural, environmental, and operational balance in smart building design.

Table 13 demonstrates that façade material selection constitutes a genuinely multidimensional decision problem in which mechanical performance, environmental impact, economic cost, constructability, and material consumption are inherently interdependent. While steel fiber composites (P4) achieve the highest compressive strength (52.3 MPa), this gain is accompanied by the highest Global Warming Potential (340 kg CO

2-eq/m

3), energy demand, material usage, and extended casting and curing time, resulting in elevated economic and constructability burdens. Conversely, hemp fiber composites (P1) exhibit a more balanced profile, offering competitive structural performance (44.7 MPa) while minimizing embodied carbon, energy demand, material consumption, and construction complexity. Intermediate configurations (P2 and P3) occupy transitional positions, illustrating that incremental strength improvements are associated with progressively higher environmental and resource-related costs.

These results confirm that optimizing façade composites based solely on mechanical strength or environmental indicators is insufficient for practical decision making. Instead, the proposed framework enables a holistic comparison in which cost, casting time, and material consumption are incorporated as complementary decision dimensions using relative indices and qualitative categories. By embedding these additional criteria within the same decision-support structure, the framework provides designers and stakeholders with transparent insight into trade-offs that directly affect feasibility, sustainability, and constructability. This multidimensional perspective responds directly to the need identified by the reviewer and reinforces the practical relevance of the proposed BIM-integrated AI-LCA approach for real-world façade design.

The counterfactual trade-off analysis in

Table 14 moves beyond intuitive feature-importance rankings by explicitly quantifying how targeted design interventions alter the coupled relationship between mechanical performance and environmental impact. Incremental increases in fiber volume fraction (CF-1 and CF-2) consistently improve predicted compressive strength but at the cost of increased GWP, confirming a nonlinear strength–carbon coupling that cannot be inferred from attribution alone. More importantly, the fiber-type substitution scenarios under matched target strength (CF-3 and CF-4) reveal asymmetric sustainability penalties: achieving equivalent strength with steel fibers results in a substantially higher GWP compared to hemp-based alternatives, whereas substituting steel with hemp at constant strength yields notable carbon savings. This demonstrates that fiber selection decisions dominate lifecycle outcomes even when structural requirements are fixed.

Curing-regime and mix-design counterfactuals (CF-5 and CF-6) further illustrate secondary but non-negligible trade-offs. Extended curing improves strength with a modest environmental penalty, while reductions in the water–cement ratio enhance mechanical performance with mixed effects on GWP depending on the associated material intensity. Collectively, these counterfactual results show that multiple design pathways can satisfy structural constraints but with markedly different sustainability consequences. By explicitly exposing these trade-offs, the proposed AI-LCA framework transforms explainability outputs into actionable decision support, enabling designers to select façade configurations that balance strength targets against lifecycle carbon objectives rather than relying on heuristic or single-metric optimization. Despite its balanced sustainability profile, hemp fiber composites may present limitations related to long-term durability, moisture sensitivity, and regional supply-chain availability, which can constrain their applicability in aggressive climates or high-load structural façade systems.

Table 15 moves the framework beyond prediction accuracy by explaining

which controllable design variables drive sustainability outcomes. For example, the dominance of binder-related variables in GWP and embodied energy indicates that low-carbon performance is primarily governed by cement intensity and substitution strategies (SCM ratio), while fiber type and volume fraction act as coupled levers that must satisfy mechanical constraints without inducing disproportionate lifecycle penalties. In practical façade design, this enables targeted interventions (prioritize binder–SCM optimization first, then tune fiber configuration for ductility and crack control) and supports transparent MCDA-Pareto selection where stakeholders can justify why a chosen configuration achieves a specific GWP reduction while preserving structural safety.

Discussion: Methodological Novelty and Implications of Dual Prediction

A central insight emerging from

Table 16 is that the majority of existing AI-driven studies in civil, structural, and sustainability engineering address

either performance

or sustainability as isolated objectives, or they couple them through sequential, toolchain-dependent workflows. Foundational contributions such as the SHM framework of [

12] formalize end-to-end data-driven reasoning and clearly identify the importance of robustness, feature sensitivity, and false-alarm risk. However, these contributions remain conceptual and domain-specific without providing a computationally integrated pathway for lifecycle-aware decision making or BIM-enabled deployment. As such, they establish methodological principles rather than delivering operational decision-support systems.

At the material and component scale, Pawlak [

13] demonstrates that machine learning can achieve high predictive fidelity for mechanical and thermo-physical properties when trained on carefully curated experimental datasets. The reported numerical results (MAE values on the order of a few MPa for strength prediction and low RSE for ensemble regressors) confirm that ML surrogates are sufficiently accurate for design-oriented material screening. Nevertheless, as summarized in

Table 16, these models are intrinsically single domain: sustainability impacts remain implicit and external to the learning process, and design decisions still require a posteriori environmental evaluation. This separation limits scalability when the design space expands and prevents a direct trade-off analysis between structural feasibility and lifecycle impact.

Probabilistic sustainability frameworks such as that of Xia et al. [

14] advance the state of the art by explicitly coupling structural reliability and environmental impact through stochastic modeling and Monte Carlo simulation. Their numerical results clearly demonstrate that sustainability outcomes are highly sensitive to reuse strategies, climate assumptions, and degradation modeling with reported sustainability probabilities ranging from below 5% to nearly 90%. While this rigor is essential for long-term policy and reliability studies, the computational burden (up to

simulated degradation paths) and analytical formulation make such approaches difficult to integrate into early-stage façade design workflows or real-time digital twins, where rapid iteration and responsiveness are critical.

BIM-centric decision-support architectures, exemplified by [

2], address a different but equally important challenge: the semantic and organizational integration of heterogeneous building data. These frameworks enable interoperability across BIM, simulation outputs, and operational data streams, thereby laying the groundwork for data-informed design. However, as highlighted by the comparison table, they do not instantiate predictive intelligence that jointly estimates mechanical performance and lifecycle indicators. Instead, they rely on external analytics or rule-based reasoning, leaving unresolved the question of how sustainability and performance trade-offs can be evaluated quantitatively and consistently at scale.

The comparison further illustrates that methodological maturity in machine learning—such as that achieved in SCADA–IoT cybersecurity applications [

9]—does not automatically translate to sustainability-aware engineering decision support. Although these pipelines achieve very high classification accuracy (RF accuracy exceeding 98%), they are optimized for detection tasks in a different problem space and do not address multi-criteria trade-offs, lifecycle reasoning, or BIM interoperability. Their inclusion in

Table 16 underscores that predictive accuracy alone is insufficient to claim novelty in sustainability-oriented design contexts.

The proposed framework operationalizes dual prediction as a unified, multi-output surrogate learning problem in which façade design variables and BIM-context features are mapped simultaneously to structural and durability-related responses and lifecycle sustainability indicators. This joint learning formulation represents a substantive methodological advance over sequential or loosely coupled pipelines. By producing trade-off-ready outputs in a single inference pass, the framework enables a direct comparison of alternative façade configurations without repeated simulation or manual LCA re-mapping, thereby substantially improving scalability for large design spaces.