Mapping Fake News Research in Digital Media: A Bibliometric and Topic Modeling Analysis of Global Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Document Types

3.2. Characteristics of Publication Outputs

3.3. Journals

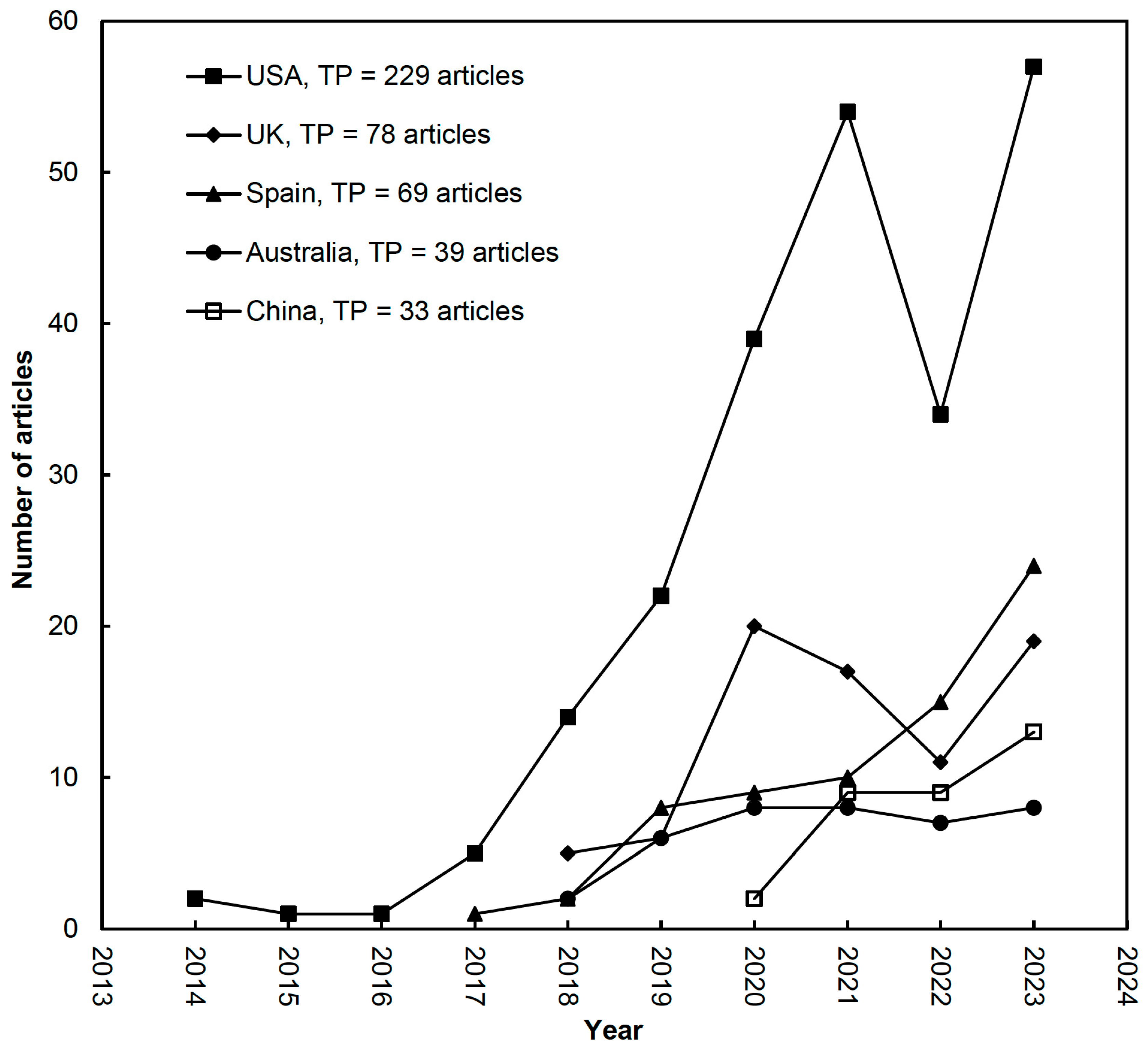

3.4. Publication Performances: Countries and Institutions

3.5. Publication Performances: Authors

3.6. The Top Ten Most Frequently Cited Articles in Fake News in Digital Media Research

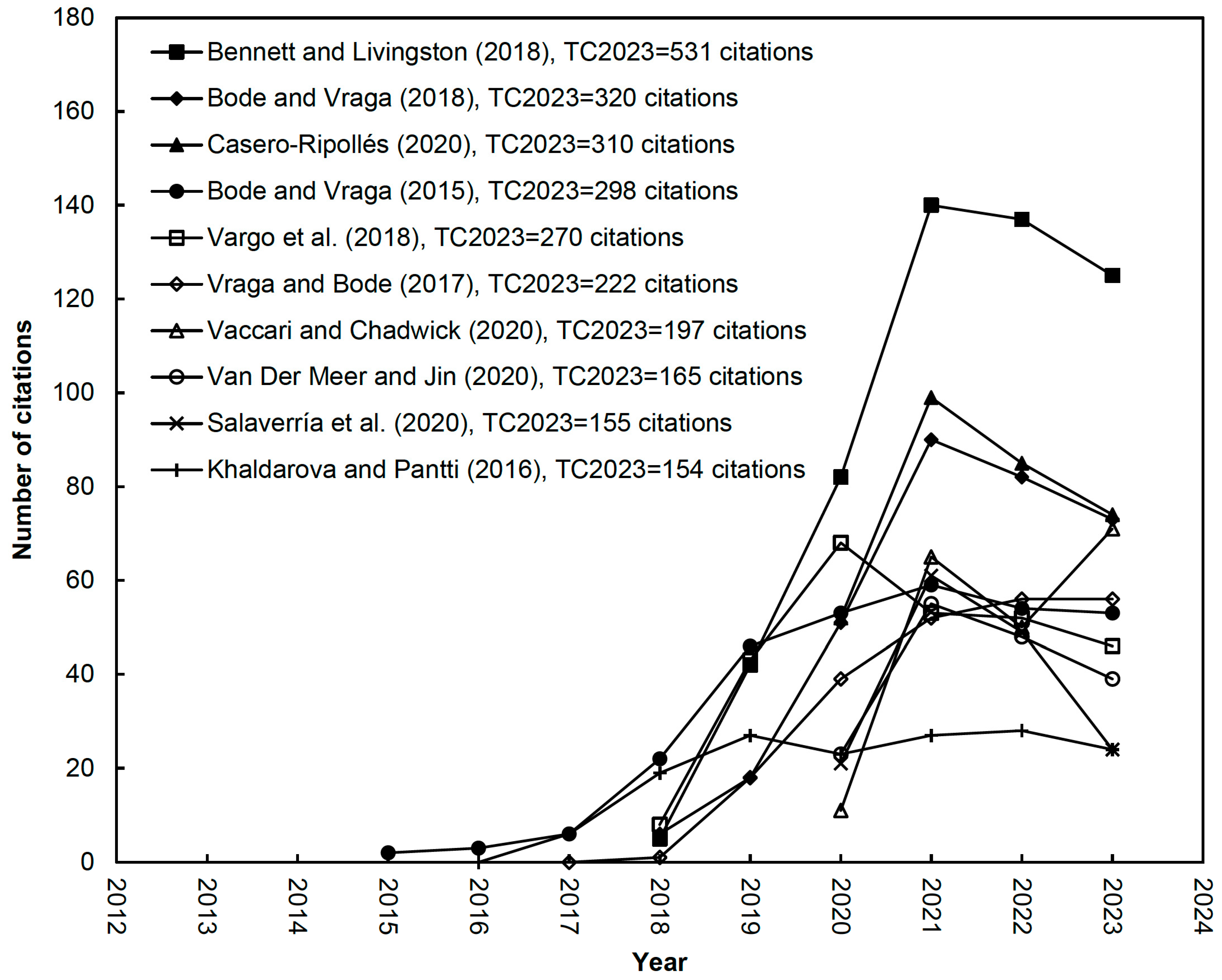

- Bennett and Livingston’s “The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions” (TC2023 = 531; C2023 = 125) stands as the most influential publication in this field [14]. The study offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how disinformation undermines democratic institutions, linking theoretical insights with real-world cases such as the Trump presidency and the Brexit campaign.

- Bode and Vraga’s “See something, say something: Correction of global health misinformation on social media” (TC2023 = 320; C2023 = 73) ranked second in total and third in annual citations [38]. Rather than critiquing social media’s role in spreading health misinformation, the study demonstrated its corrective potential through a simulated Facebook News Feed experiment that incorporated both algorithmic and user-generated interventions. The findings highlighted the importance of social media campaigns in debunking false or misleading health information and providing sources that support accurate facts. It has maintained its importance since its publication in 2018, and the number of citations, which peaked especially during the global pandemic, has continued to rise to date. (see Figure 4).

- Casero-Ripollés’ “Impact of COVID-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of news consumption during the outbreak” (TC2023 = 310; C2023 = 74) ranked third in total and second in annual citations [45]. The study explored how the pandemic transformed news consumption, media credibility, and citizens’ ability to detect fake news, highlighting its broader social and communicative impacts. Although citation activity has slightly decreased after the pandemic, the article remains one of the most influential works in the field (see Figure 4).

- Bode and Vraga’s “In related news, that was wrong: The correction of misinformation through related stories functionality in social media” (TC2023 = 298; C2023 = 53) ranked fourth in total citations and sixth in annual citations [28]. This seminal 2015 study marked a paradigm shift in misinformation correction, emphasizing the potential of social media platforms to empower users in addressing false information. Its innovative approach has ensured continued relevance, keeping it among the top ten most influential works in the field.

- Vargo, Guo, and Amazeen’s “The agenda-setting power of fake news: A big data analysis of the online media landscape from 2014 to 2016” (TC2023 = 271; C2023 = 46) ranked fifth in total citations [15]. Analyzing online media from 2014 to 2016, the study examined the rising impact of fake news during the U.S. presidential elections, emphasizing its societal and political effects. The effects of fake news on society and the consequences of these effects have garnered significant attention not only in academic circles but also in the media, politics, and the public.

- Vraga and Bode’s “Using expert sources to correct health misinformation in social media” (TC2023 = 222; C2023 = 56) ranked sixth in total and fifth in annual citations [39]. This pre-pandemic experimental study highlighted the importance of expert sources in correcting health misinformation on digital platforms. Its relevance increased during the COVID-19 outbreak, emphasizing its significance in health communication literature.

- Vaccari and Chadwick’s “Deepfakes and disinformation: Exploring the impact of synthetic political video on deception, uncertainty, and trust in news” (TC2023 = 197; C2023 = 71) ranked seventh in total and fourth in annual citations [46]. This pioneering study investigated how synthetic political videos influence deception, uncertainty, and trust in news. Unlike pandemic-related misinformation studies, it demonstrated sustained and growing academic interest in deepfake technologies, establishing a solid foundation for future research on the evolving dynamics of political communication (see Figure 4). Deepfakes have such high potential to pose serious threats such as public opinion manipulation, geopolitical tensions, chaos in financial markets, fraud, slander, and identity theft that studies in this area will continue to attract attention among academics [47].

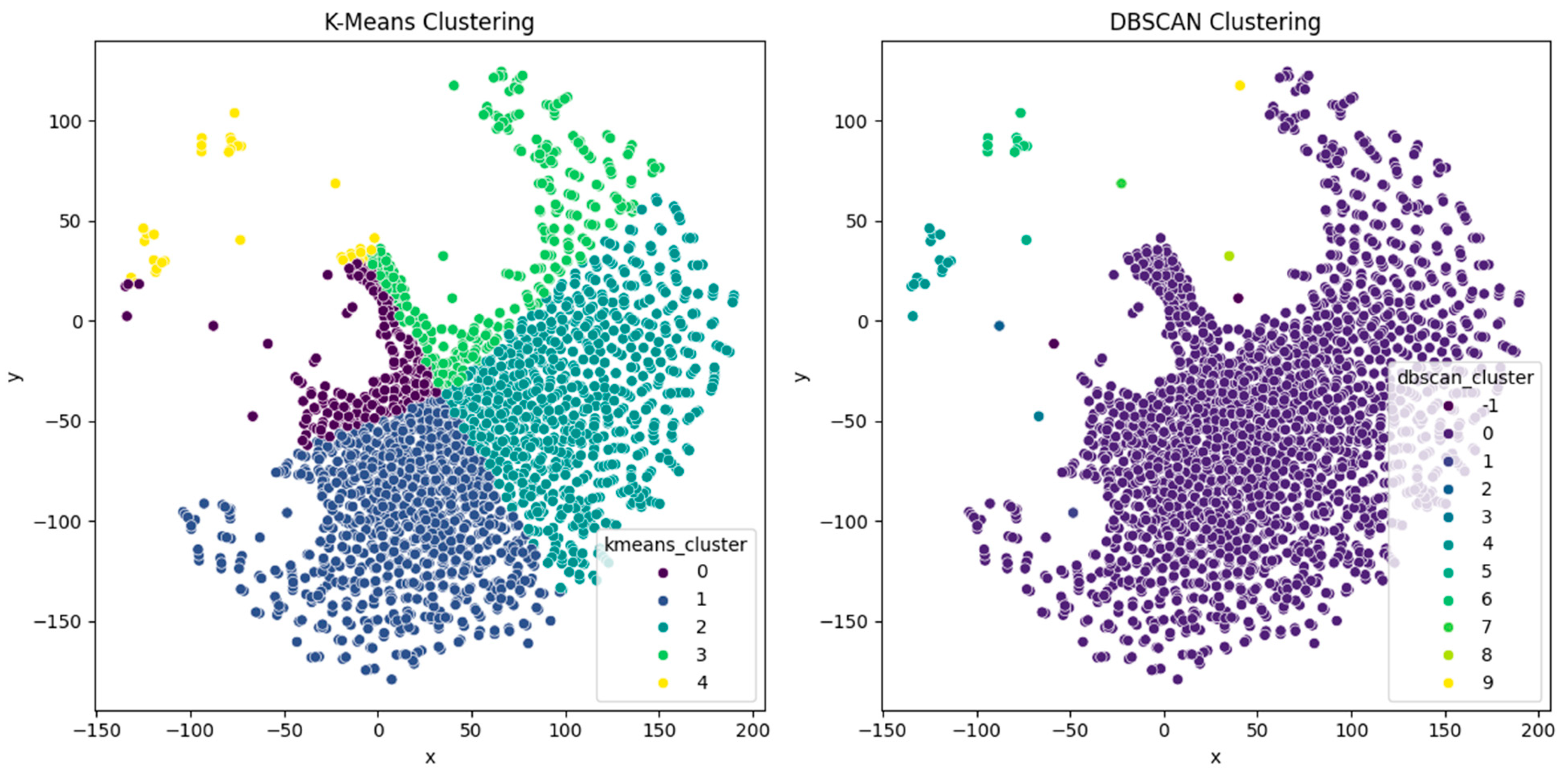

3.7. Research Foci and Topic Modeling

3.7.1. Topic 1: Digital Media and Audience Engagement

3.7.2. Topic 2: Social and Political Implications of Media

3.7.3. Topic 3: Information Credibility and Cognitive Aspects

3.7.4. Topic 4: Crisis Communication and Societal Challenges

3.7.5. Topic 5: Social Issues and Dynamics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statements

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, R.M. Social Media and Free Speech: A Collision Course That Threatens Democracy. Ohio North. Univ. Law Rev. 2023, 49, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N. From Social Media to Social Ministry: A Guide to Digital Discipleship; Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, A.; Tandoc, E.; Ling, R. Too Good to Be True, Too Good Not to Share: The Social Utility of Fake News. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 23, 1965–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Ghosh, M. Bibliometric Review of Research on Misinformation: Reflective Analysis on the Future of Communication. J. Creat. Commun. 2023, 18, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ferrándiz, R. An Overview of the Fake News Phenomenon: From Untruth-Driven to Post-Truth-Driven Approaches. Media Commun. 2023, 11, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Lim, D.; Ling, R. Diffusion of Disinformation: How Social Media Users Respond to Fake News and Why. Journalism 2020, 21, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazer, D.M.J.; Baum, M.A.; Benkler, Y.; Berinsky, A.J.; Greenhill, K.M.; Menczer, F.; Metzger, M.J.; Nyhan, B.; Pennycook, G.; Rothschild, D.; et al. The Science of Fake News. Science 2018, 359, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C. Fake News. It’s Complicated. First Draft 2017, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missau, L.D. The Role of Social Sciences in the Study of Misinformation: A Bibliometric Analysis of Web of Science and Scopus Publications (2017–2022). Tripodos 2024, 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M.; Nasar, A.; Arshad-Ayaz, A. A Bibliometric Analysis of Disinformation through Social Media. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2022, 12, e202242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, D.; González Pardo, R.E.; Cortés Peña, O. Post-Truth and Fake News in Scientific Communication in Ibero-American Journals. Comun. Y Soc. 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, V.; Thomas, T.; Nellanat, P.D. Mapping Fake News and Misinformation in Media: A Two-Decade Bibliometric Review of Emerging Trends. Insight-News Media 2025, 8, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W.L.; Livingston, S. The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions. Eur. J. Commun. 2018, 33, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, C.J.; Guo, L.; Amazeen, M.A. The Agenda-Setting Power of Fake News: A Big Data Analysis of the Online Media Landscape from 2014 to 2016. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 2028–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adalı, G.; Yardibi, F.; Aydın, Ş.; Güdekli, A.; Aksoy, E.; Hoştut, S. Gender and Advertising: A 50-Year Bibliometric Analysis. J. Advert. 2025, 54, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Ho, Y.-S. Research Trend of Metal–Organic Frameworks: A Bibliometric Analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 109, 481–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-S. Comments on the Reply to the Rebuttal to: Zhu, Jin, & He ‘On Evolutionary Economic Geography: A Literature Review Using Bibliometric Analysis’, European Planning Studies Vol. 27, Pp 639–660. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-S. Top-Cited Articles in Chemical Engineering in Science Citation Index Expanded: A Bibliometric Analysis. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 20, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Hui, Z.F.; Yuh, S.H. Comparison of universities’scientific performance using bibliometric indicators. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2011, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.; Kahn, M. A Bibliometric Study of Highly Cited Reviews in the Science Citation Index Expanded TM. Asso. Info. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific, L.L. Advancements in Dynamic Topic Modeling: A Comparative Analysis of LDA, DTM, GibbsLDA++, HDP and Proposed Hybrid Model HDP with CT-DTM for Real-Time and Evolving Textual Data. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2024, 102, 4344–4360. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, D. DBSCAN Clustering Algorithm Based on Density. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Forum on Electrical Engineering and Automation (IFEEA), Hefei, China, 25–27 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 949–953. [Google Scholar]

- Monge-Nájera, J.; Ho, Y.-S. El Salvador Publications in the Science Citation Index Expanded: Subjects, Authorship, Collaboration and Citation Patterns. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2017, 65, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Ho, Y.-S. A Bibliometric Study of the Fenton Oxidation for Soil and Water Remediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.-S. The Top-Cited Research Works in the Science Citation Index Expanded. Scientometrics 2013, 94, 1297–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirkkonen, P.; Luoma-aho, V. Online Authority Communication during an Epidemic: A Finnish Example. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. In Related News, That Was Wrong: The Correction of Misinformation through Related Stories Functionality in Social Media. J. Commun. 2015, 65, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-S. A Bibliometric Analysis of Highly Cited Publications in Web of Science Category of Emergency Medicine. Signa Vitae 2021, 17, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Omega, P.D.; Parung, J.; Yuwanto, L.; Ho, Y.-S. A Bibliometric Analysis of Positive Mental Health Research and Development in the Social Science Citation Index. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. (IJMHP) 2024, 26, 817–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenberg, D.; Lundberg, G.D. The Order of Authorship: Who’s on First? JAMA 1990, 264, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.-S.; Mukul, S.A. Publication Performance and Trends in Mangrove Forests: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, N.; Joseph, K.; Friedland, L.; Swire-Thompson, B.; Lazer, D. Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Science 2019, 363, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, M.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C.; Lenhart, A.; Madden, M. Social Media Update 2014. Pew Res. Cent. 2015, 19, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, T.; Puscher, D.; Strufe, T. The User Behavior in Facebook and Its Development from 2009 until 2014. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.04943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.; Kaiser, J.; Vaccari, C.; Freeman, D.; Lambe, S.; Loe, B.S.; Vanderslott, S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Conroy, M.; Ross, A.R.N.; et al. Online social endorsement and Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United Kingdom. Social Soc. Media + Soc. 2021, 7, 20563051211008817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-S.; Fülöp, T.; Krisanapan, P.; Soliman, K.M.; Cheungpasitporn, W. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Trends in Kidney Care. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 367, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, L.; Vraga, E.K. See Something, Say Something: Correction of Global Health Misinformation on Social Media. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vraga, E.K.; Bode, L. Using Expert Sources to Correct Health Misinformation in Social Media. Sci. Commun. 2017, 39, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, M.; Powell, T.E.; Van Der Meer, T.G.L.A.; Bos, L. A Picture Paints a Thousand Lies? The Effects and Mechanisms of Multimodal Disinformation and Rebuttals Disseminated via Social Media. Political Commun. 2020, 37, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameleers, M.; Brosius, A.; De Vreese, C.H. Whom to Trust? Media Exposure Patterns of Citizens with Perceptions of Misinformation and Disinformation Related to the News Media. Eur. J. Commun. 2022, 37, 237–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, V.; Paris, B.; Donovan, J.; Hameleers, M.; Roozenbeek, J.; Van Der Linden, S.; Von Sikorski, C. Visual Mis- and Disinformation, Social Media, and Democracy. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2021, 98, 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E.C.; Lim, Z.W.; Ling, R. Defining “Fake News”: A Typology of Scholarly Definitions. Digit. Journal. 2018, 6, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.-T.; Ho, Y.-S. Bibliometric Analysis of Tsunami Research. Scientometrics 2007, 73, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, A. Impact of COVID-19 on the Media System. Communicative and Democratic Consequences of News Consumption during the Outbreak. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, C.; Chadwick, A. Deepfakes and Disinformation: Exploring the Impact of Synthetic Political Video on Deception, Uncertainty, and Trust in News. Soc. Media + Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120903408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambín, Á.F.; Yazidi, A.; Vasilakos, A.; Haugerud, H.; Djenouri, Y. Deepfakes: Current and Future Trends. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Document Type | TP | % | AU | APP | TC2023 | CPP2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | 600 | 92 | 1617 | 2.7 | 12,476 | 21 |

| Early access | 28 | 4.3 | 87 | 3.1 | 14 | 0.50 |

| Editorial material | 20 | 3.1 | 48 | 2.4 | 433 | 22 |

| Review | 19 | 2.9 | 59 | 3.1 | 218 | 11 |

| Book review | 12 | 1.8 | 13 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.083 |

| Correction | 1 | 0.15 | 2 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Proceedings paper | 1 | 0.15 | 1 | 1.0 | 4 | 4.0 |

| Journal | TP (%) | R (IF2023) | AU | APP | TC2023 | CPP2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media + Society | 70 (12) | 4 (5.5) | 204 | 2.9 | 1354 | 19 |

| International Journal of Communication | 52 (8.7) | 57 (1.9) | 128 | 2.5 | 354 | 6.8 |

| Profesional De La Informacion | 41 (6.8) | 39 (2.6) | 125 | 3.0 | 898 | 22 |

| New Media & Society | 39 (6.5) | 14 (4.5) | 118 | 3.0 | 1557 | 40 |

| Digital Journalism | 35 (5.8) | 8 (5.2) | 88 | 2.5 | 699 | 20 |

| Media and Communication | 34 (5.7) | 35 (2.7) | 83 | 2.4 | 246 | 7.2 |

| Information Communication & Society | 25 (4.2) | 17 (4.2) | 60 | 2.4 | 863 | 35 |

| Journalism Practice | 21 (3.5) | 49 (2.2) | 52 | 2.5 | 445 | 21 |

| Health Communication | 21 (3.5) | 29 (3.0) | 77 | 3.7 | 899 | 43 |

| Political Communication | 20 (3.3) | 12 (4.6) | 62 | 3.1 | 708 | 35 |

| Country | TP | TP (n = 600) | IPC (n = 454) | CPC (n = 146) | FP (n = 600) | RP (n = 600) | SP (n = 140) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | ||

| USA | 229 | 1 (38) | 29 | 1 (35) | 32 | 1 (48) | 22 | 1 (32) | 29 | 1 (32) | 29 | 1 (34) | 16 |

| UK | 78 | 2 (13) | 23 | 3 (8.4) | 23 | 2 (27) | 24 | 3 (9.2) | 22 | 3 (9.3) | 22 | 2 (10) | 14 |

| Spain | 69 | 3 (12) | 16 | 2 (13) | 17 | 8 (8.2) | 14 | 2 (10) | 16 | 2 (11) | 16 | 3 (9.3) | 31 |

| Australia | 39 | 4 (6.5) | 23 | 4 (5.9) | 24 | 8 (8.2) | 22 | 4 (5.3) | 27 | 4 (5.3) | 24 | 4 (6.4) | 26 |

| China | 33 | 5 (5.5) | 14 | 5 (3.5) | 6.9 | 3 (12) | 20 | 5 (4.5) | 14 | 5 (4.2) | 10 | 14 (1.4) | 3.0 |

| Singapore | 29 | 6 (4.8) | 28 | 7 (3.1) | 30 | 5 (10) | 26 | 6 (3.8) | 30 | 6 (4.0) | 30 | 5 (2.9) | 21 |

| The Netherlands | 29 | 6 (4.8) | 18 | 5 (3.5) | 14 | 6 (8.9) | 23 | 7 (3.5) | 19 | 7 (3.8) | 18 | 5 (2.9) | 20 |

| Germany | 26 | 8 (4.3) | 19 | 9 (2.0) | 12 | 3 (12) | 23 | 9 (2.7) | 18 | 8 (3.5) | 23 | 5 (2.9) | 14 |

| Canada | 25 | 9 (4.2) | 10 | 8 (2.6) | 12 | 6 (8.9) | 8.9 | 8 (2.8) | 11 | 9 (2.7) | 10 | 14 (1.4) | 18 |

| South Africa | 13 | 10 (2.2) | 11 | 11 (1.1) | 15 | 11 (5.5) | 8.8 | 17 (1.0) | 15 | 14 (1.2) | 16 | 9 (2.1) | 20 |

| Belgium | 13 | 10 (2.2) | 7.3 | 11 (1.1) | 4.2 | 11 (5.5) | 9.3 | 17 (1.0) | 3.5 | 19 (1.0) | 3.5 | 5 (2.9) | 6.8 |

| 6 | TP | TP (n = 600) | IPI (n = 307) | CPI (n = 293) | FP (n = 600) | RP (n = 600) | SP (n = 140) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | R (%) | CPP2023 | ||

| U Oxford | 24 | 1 (4.0) | 26 | 7 (1.3) | 26 | 1 (6.8) | 26 | 3 (2.0) | 22 | 4 (1.8) | 25 | 4 (1.4) | 36 |

| U Amsterdam | 22 | 2 (3.7) | 21 | 1 (4.2) | 16 | 6 (3.1) | 27 | 1 (3.0) | 22 | 1 (3.2) | 21 | 1 (2.9) | 20 |

| NTU | 20 | 3 (3.3) | 36 | 2 (3.3) | 36 | 5 (3.4) | 35 | 2 (2.3) | 43 | 2 (2.5) | 40 | 4 (1.4) | 19 |

| UTA | 16 | 4 (2.7) | 12 | 5 (1.6) | 6.2 | 4 (3.8) | 15 | 6 (1.3) | 7.6 | 6 (1.3) | 7.6 | 4 (1.4) | 10 |

| UWM | 16 | 4 (2.7) | 46 | 3 (2.3) | 68 | 6 (3.1) | 28 | 4 (1.8) | 56 | 3 (2.0) | 52 | 4 (1.4) | 26 |

| U Minnesota | 14 | 6 (2.3) | 38 | 53 (0.33) | 86 | 2 (4.4) | 34 | 7 (1.2) | 41 | 8 (1.2) | 58 | 20 (0.71) | 86 |

| QUT | 12 | 7 (2.0) | 32 | 3 (2.3) | 45 | 19 (1.7) | 13 | 5 (1.5) | 38 | 5 (1.5) | 38 | 2 (2.1) | 46 |

| Georgetown U | 12 | 7 (2.0) | 81 | N/A | N/A | 3 (4.1) | 81 | 31 (0.50) | 126 | 33 (0.50) | 126 | N/A | N/A |

| U Iowa | 10 | 9 (1.7) | 37 | 53 (0.33) | 7.0 | 6 (3.1) | 41 | 18 (0.67) | 25 | 18 (0.67) | 25 | 20 (0.71) | 7.0 |

| CUL | 9 | 10 (1.5) | 13 | 53 (0.33) | 1.0 | 9 (2.7) | 15 | 18 (0.67) | 14 | 14 (0.83) | 11 | 20 (0.71) | 1.0 |

| Author | TP (n = 600) | FP (n = 600) | RP (n = 600) | SP (n = 689) | h | Rank (j) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank (TP) | CPP2023 | Rank (FP) | CPP2023 | Rank (RP) | CPP2023 | Rank (SP) | CPP2023 | |||

| E.K. Vraga | 1 (14) | 102 | 2 (7) | 92 | 2 (7) | 92 | N/A | N/A | π/4 | 2 (14) |

| L. Bode | 2 (12) | 106 | 5 (4) | 169 | 4 (4) | 169 | N/A | N/A | π/4 | 5 (8) |

| M. Tully | 3 (11) | 34 | 5 (4) | 25 | 4 (4) | 25 | 6 (1) | 7.0 | π/4 | 5 (8) |

| M. Hameleers | 4 (10) | 14 | 1 (10) | 14 | 1 (10) | 14 | 1 (3) | 6.3 | π/4 | 1 (20) |

| E.C. Tandoc | 5 (8) | 56 | 3 (6) | 70 | 2 (7) | 61 | N/A | N/A | 0.8622 | 3 (13) |

| J. Lee | 5 (8) | 14 | 4 (5) | 11 | 4 (4) | 9.0 | 6 (1) | 3.0 | 0.6747 | 4 (9) |

| C. Vaccari | 7 (6) | 69 | 17 (2) | 102 | 9 (3) | 69 | N/A | N/A | 0.9828 | 16 (5) |

| J. Lukito | 7 (6) | 29 | 17 (2) | 50 | 20 (2) | 50 | 6 (1) | 50 | π/4 | 20 (4) |

| A. Chadwick | 7 (6) | 69 | 17 (2) | 104 | 20 (2) | 104 | N/A | N/A | π/4 | 20 (4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ho, Y.-S.; Yardibi, F.; Dogan, M.E.; Kusetogullari, H. Mapping Fake News Research in Digital Media: A Bibliometric and Topic Modeling Analysis of Global Trends. Information 2026, 17, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010026

Ho Y-S, Yardibi F, Dogan ME, Kusetogullari H. Mapping Fake News Research in Digital Media: A Bibliometric and Topic Modeling Analysis of Global Trends. Information. 2026; 17(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Yuh-Shan, Fatma Yardibi, Murat Ertan Dogan, and Huseyin Kusetogullari. 2026. "Mapping Fake News Research in Digital Media: A Bibliometric and Topic Modeling Analysis of Global Trends" Information 17, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010026

APA StyleHo, Y.-S., Yardibi, F., Dogan, M. E., & Kusetogullari, H. (2026). Mapping Fake News Research in Digital Media: A Bibliometric and Topic Modeling Analysis of Global Trends. Information, 17(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010026