1. Introduction

With the continuous growth in the scale and complexity of software systems, quality and security issues have become critical factors constraining system reliability. As a key stage in the software development lifecycle, testing plays a vital role in ensuring software quality, and its efficiency and effectiveness directly affect the reliability and maintainability of the system. High-quality test cases can uncover more potential defects under limited resources, thereby enhancing system robustness [

1]. However, traditional manual testing methods, which rely heavily on human expertise, are not only inefficient and limited in coverage but also difficult to adapt to the rapid iteration and high complexity of modern software systems. Consequently, automated test case generation has emerged as a major research focus.

Symbolic execution [

2,

3,

4], as an important branch of automated testing, enables systematic analysis of program paths and automatic generation of input data, theoretically achieving high test coverage. Nevertheless, in practical applications, symbolic execution suffers from critical bottlenecks such as path explosion [

5] and the high complexity of constraint solving [

6]. As the number of program branches increases exponentially, the path space rapidly expands, leading to a sharp decline in testing efficiency. How to improve path exploration efficiency and vulnerability detection accuracy while maintaining sufficient test coverage has become a central challenge in automated testing research.

In recent years, researchers have extensively explored performance optimization and intelligent enhancement of symbolic execution. Although traditional symbolic execution can systematically traverse program paths, it still struggles with path explosion and inefficient constraint solving in complex systems. To mitigate these issues, many studies have focused on optimizing path search strategies and constraint-solving mechanisms. With the rise of deep learning [

7,

8], intelligent models have been increasingly integrated into symbolic execution to guide path prediction and test generation. Approaches based on RNNs [

9] and CNNs [

10] learn sequential and structural features of program execution to identify high-value paths, while graph neural network (GNN)-based methods capture semantic dependencies within control flow [

11], improving the model’s global comprehension capability. Meanwhile, active learning [

12] has been introduced into the testing process, where uncertainty- or diversity-based sampling strategies are used to select representative samples, reduce redundant data, and enhance generalization performance.

In summary, although existing automated testing approaches have achieved notable progress in path exploration and vulnerability detection, they still suffer from the following three major limitations:

- (1)

Path explosion and omission of critical paths. Under complex branching structures, symbolic execution tends to cause exponential growth in execution paths—known as the path explosion problem. Conventional pruning or heuristic strategies, while mitigating this issue, may inadvertently omit deep or cross-module critical paths, thereby compromising testing completeness.

- (2)

Insufficient model generalization and stability. Most existing methods rely on a single predictive model or a fixed ensemble strategy, making it difficult to adapt to structural diversity across different programs. Consequently, they are prone to overfitting or performance fluctuations, lacking adaptability and robustness.

- (3)

Low sample utilization and high annotation cost. Passive or random sampling leads to under-representative training samples that fail to efficiently capture key semantic features. Meanwhile, model training often depends on extensive manual labeling, limiting scalability and efficiency.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for a unified framework that combines active learning with a dynamic ensemble mechanism to balance path exploration depth, model generalization, and sample utilization efficiency. Existing studies tend to address these limitations separately and have yet to develop an integrated solution that can simultaneously improve generalization, reduce annotation costs, and adapt to diverse program structures during symbolic execution. The Deep Active Ensemble Learning Framework (DLF) proposed in this work is designed in response to these needs, providing a more coherent and effective way to address these challenges and compensating for the shortcomings of existing approaches.

To this end, this paper proposes a Deep Active Ensemble Learning Framework (DLF) for automated test case generation. DLF is driven by active learning principles: it employs a dual-criteria sampling strategy that combines uncertainty-based and diversity-based sampling to select the most informative symbolic state samples, while introducing an adaptive dynamic ensemble mechanism to enhance model robustness and generalization.

The DLF-based symbolic execution process consists of two stages:

Training phase: Guided by active learning, DLF performs uncertainty-driven sampling and similarity-constrained data selection to dynamically update the training set, thereby improving model learning efficiency.

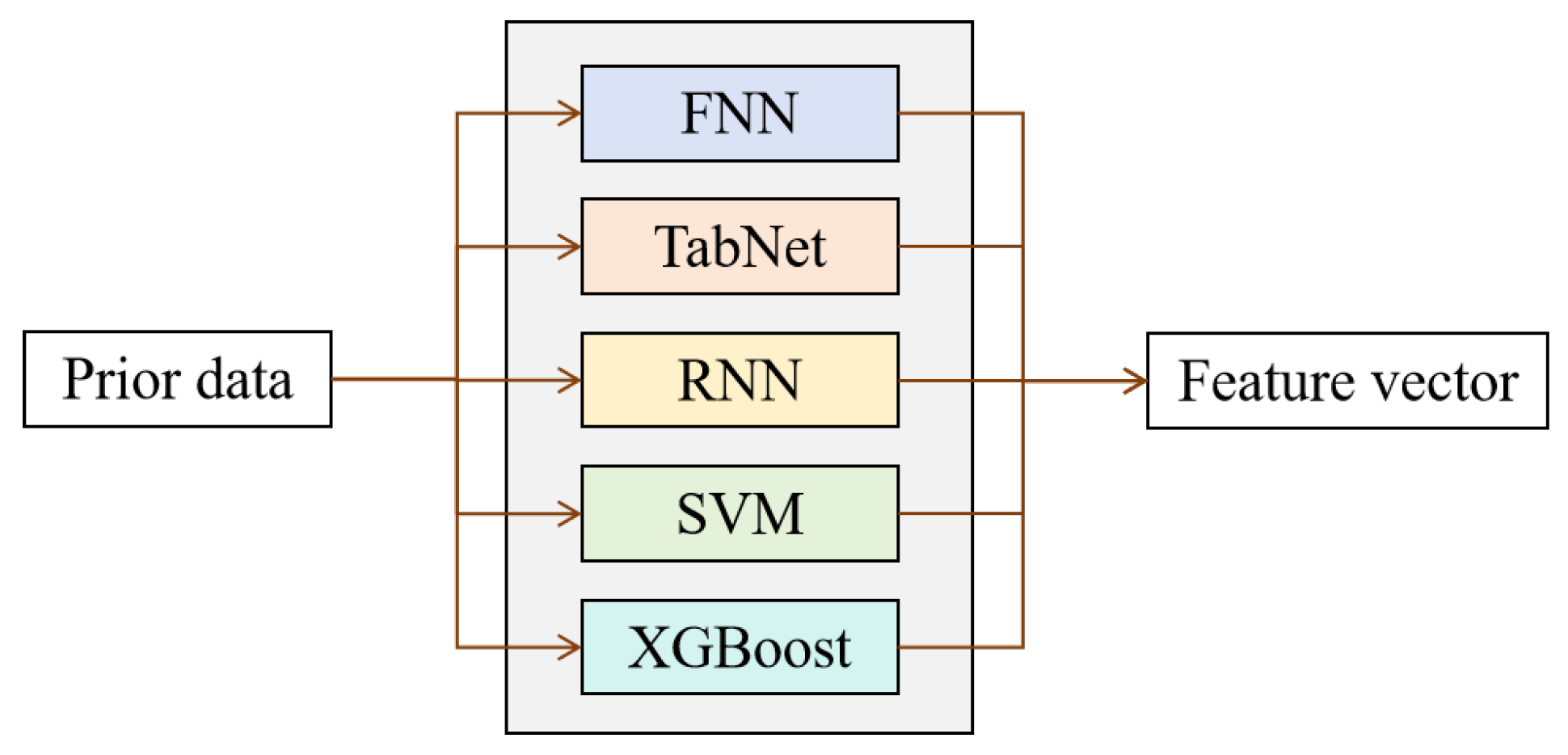

Testing phase: Within a heterogeneous model pool—comprising Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN), TabNet, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and XGBoost—DLF adaptively selects the optimal model combination according to sample-level feature similarity to perform path prediction and test case generation.

In addition, DLF incorporates a Gated Graph Neural Network (GGNN) [

13] architecture to extract multidimensional features from the Control Flow Graph (CFG) [

14], strengthening its understanding of program-level dependencies and semantic structures. Furthermore, a branch-density-based dynamic sliding-window mechanism is designed to adaptively adjust the search scope according to path complexity, achieving a dynamic balance between exploration depth and computational efficiency and effectively alleviating the path explosion problem.

The main innovations of the proposed approach are summarized as follows:

- (1)

Vulnerability-probability-driven active guidance mechanism. DLF predicts the vulnerability probability of symbolic states based on source-code features and prioritizes the exploration of states with higher vulnerability likelihood. By integrating active learning with ensemble learning, DLF iteratively refines its classifier, thereby improving test-case quality while reducing labeling costs.

- (2)

Dynamic ensemble strategy with a heterogeneous model pool. During the testing phase, DLF constructs a heterogeneous model pool composed of Feedforward Neural Networks (FNN) [

15], TabNet [

16], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) [

9], Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

17], and XGBoost [

18]. It dynamically selects and adaptively weights the optimal model combination according to sample similarity, fully leveraging the complementary strengths of different models to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness.

- (3)

Dynamic sliding-window and graph-feature modeling mechanism. A branch-density-based dynamic sliding window is designed to adaptively regulate exploration depth, while a Gated Graph Neural Network (GGNN) is employed to extract structural features from the Control Flow Graph (CFG), strengthening semantic understanding of program dependencies and alleviating the path-explosion problem.

- (4)

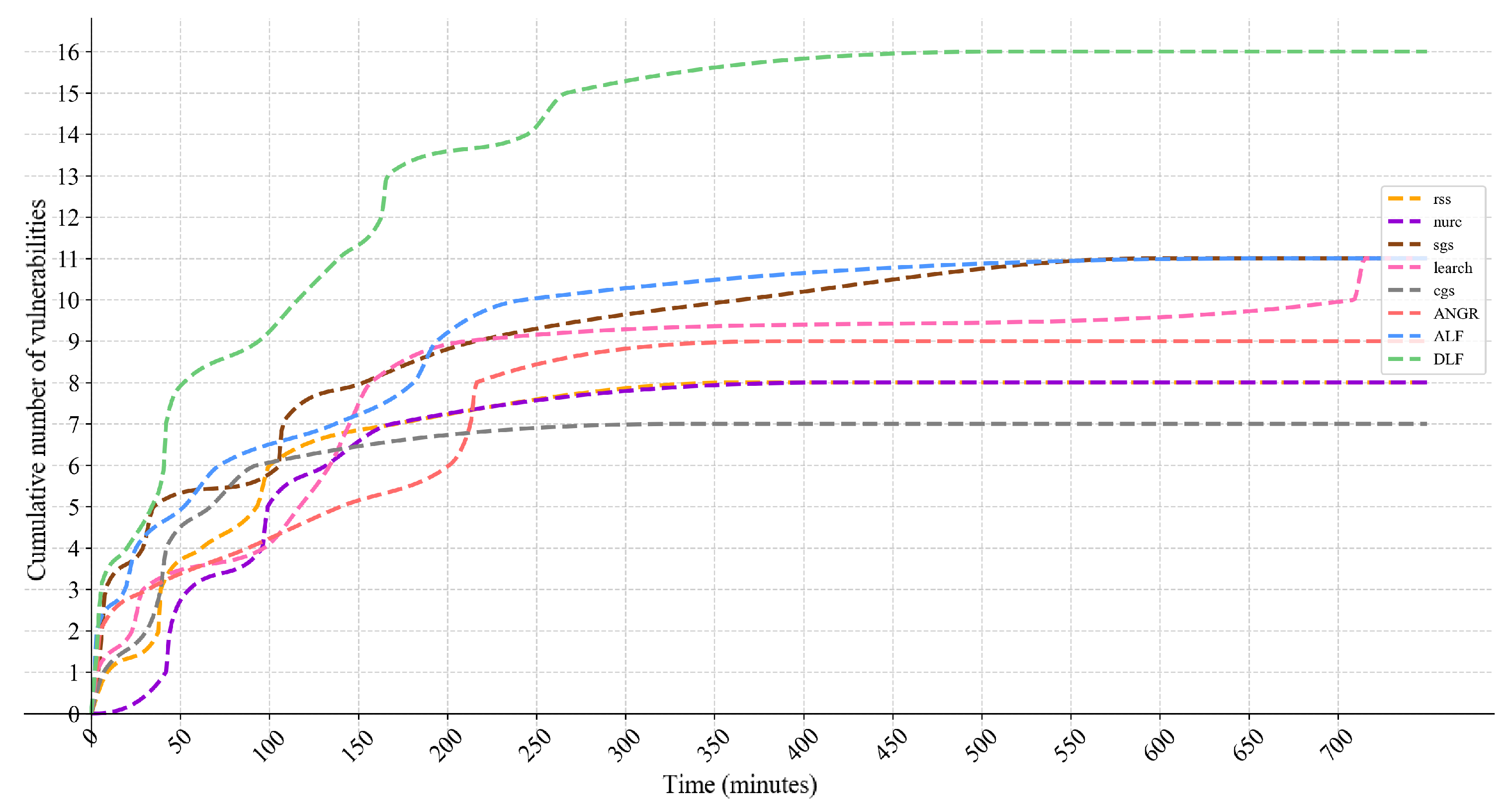

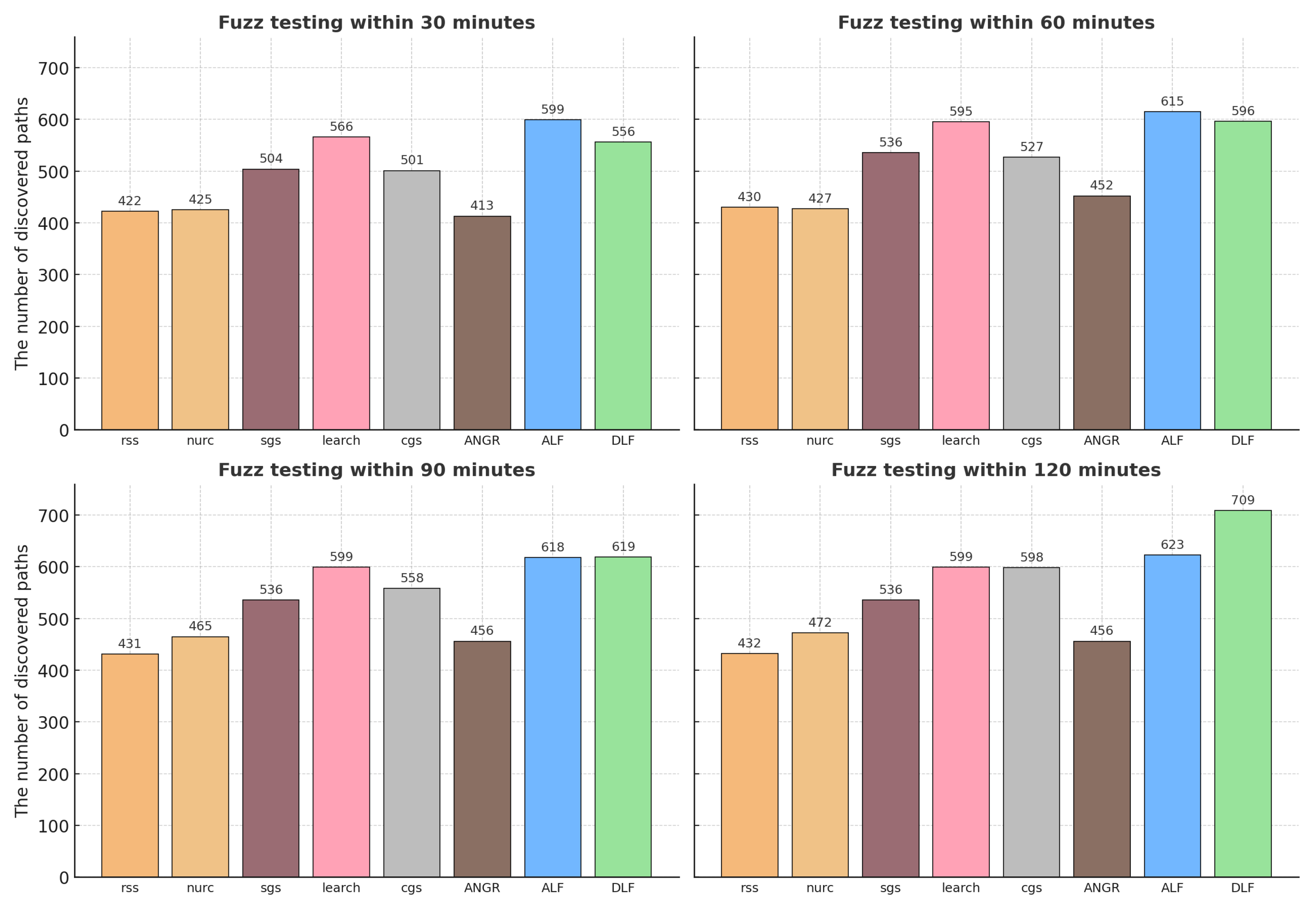

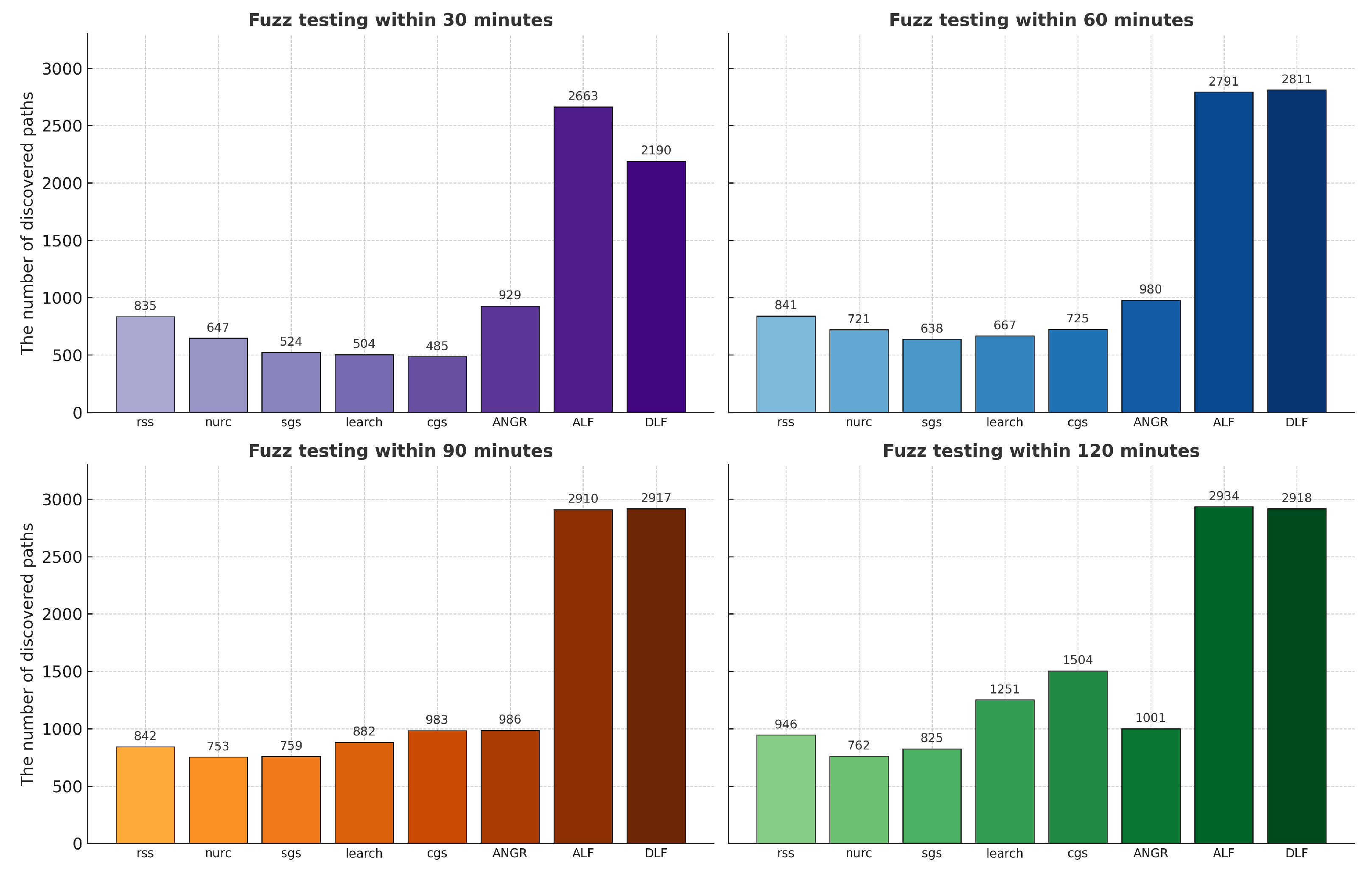

Extensive empirical validation on multiple datasets. The effectiveness of DLF is evaluated on several real-world benchmark datasets. Experimental results demonstrate that DLF consistently outperforms existing methods in terms of vulnerability detection rate, path coverage, and execution efficiency.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work;

Section 3 presents the overall design and key techniques of DLF;

Section 4 reports the experimental setup and results;

Section 5 concludes the paper; and

Section 6 outlines future work and suggestions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and D.Z.; methodology, Y.L.; software, D.Z.; validation, Y.P.; formal analysis, Y.P.; investigation, D.Z.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.P.; visualization, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy considerations.

Acknowledgments

We express our heartfelt gratitude to the reviewers and editors for their meticulous work.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yaogang Lu was employed by Beijing New Building Materials Public Limited Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Khan, M.E.; Khan, F. Importance of software testing in software development life cycle. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Issues (IJCSI) 2014, 11, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Kurian, E.; Briola, D.; Braione, P.; Denaro, G. Automatically generating test cases for safety-critical software via symbolic execution. J. Syst. Softw. 2023, 199, 111629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, R.; Coppa, E.; D’elia, D.C.; Demetrescu, C.; Finocchi, I. A survey of symbolic execution techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susag, Z.; Lahiri, S.; Hsu, J.; Roy, S. Symbolic execution for randomized programs. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2022, 6, 1583–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sivanrupan, G.; Tsankov, P.; Vechev, M. Learning to explore paths for symbolic execution. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual Event, Republic of Korea, 15–19 November 2021; pp. 2526–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Xu, H.; Bi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y. Boosting symbolic execution via constraint solving time prediction (experience paper). In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Virtual, Denmark, 11–17 July 2021; pp. 336–347. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero-Holgueras, J.; Pastrana, S. HEFactory: A symbolic execution compiler for privacy-preserving Deep Learning with Homomorphic Encryption. SoftwareX 2023, 22, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Qasim, A.; Mehak, G.; Kolesnikova, O.; Gelbukh, A.; Sidorov, G. ORUD-Detect: A Comprehensive Approach to Offensive Language Detection in Roman Urdu Using Hybrid Machine Learning–Deep Learning Models with Embedding Techniques. Information 2025, 16, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, X.; Hu, C.; Liu, Y. Detecting condition-related bugs with control flow graph neural network. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 July 2023; pp. 1370–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, D.M.; Nguyen, T.S. FA-Seed: Flexible and Active Learning-Based Seed Selection. Information 2025, 16, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Du, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, P. Traffic-GGNN: Predicting traffic flow via attentional spatial-temporal gated graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 18423–18432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Torri, S.A.; Mittal, S. Survey of malware analysis through control flow graph using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom), Exeter, UK, 1–3 November 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1554–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C.; Ding, W.; Zhan, J. GA-FCFNN: A new forecasting method combining feature selection methods and feedforward neural networks using genetic algorithms. Inf. Sci. 2024, 669, 120566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Tan, X.; Wen, L.; Gao, Q.; Wang, W. Privacy-Preserving and Interpretable Grade Prediction: A Differential Privacy Integrated TabNet Framework. Electronics 2025, 14, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.X.; Chien, W.; Chiu, C.C.; Cheng, Y.T. Application of support vector machine (SVM) in the sentiment analysis of twitter dataset. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Nidhra, S.; Dondeti, J. Black box and white box testing techniques-a literature review. Int. J. Embed. Syst. Appl. (IJESA) 2012, 2, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, M.; Müller, P.; Wüstholz, V. Guiding dynamic symbolic execution toward unverified program executions. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Software Engineering, Austin, TX, USA, 14–22 May 2016; pp. 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Avgerinos, T.; Rebert, A.; Cha, S.K.; Brumley, D. Enhancing symbolic execution with veritesting. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Software Engineering, Hyderabad, India, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 1083–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Păsăreanu, C.S.; Visser, W. A survey of new trends in symbolic execution for software testing and analysis. Int. J. Softw. Tools Technol. Transf. 2009, 11, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Lu, M. SPOT: Testing stream processing programs with symbolic execution and stream synthesizing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sheng, S.; Wang, Y. A systematic literature review on smart contract vulnerability detection by symbolic execution. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Blockchain and Trustworthy Systems, Haikou, China, 8–10 August 2023; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 226–241. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrante, J.; Ottenstein, K.J.; Warren, J.D. The program dependence graph and its use in optimization. ACM Trans. Program. Lang. Syst. (TOPLAS) 1987, 9, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, T.J. A complexity measure. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 1976, SE-2, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, T.; Rajamani, S.K. Automatically validating temporal safety properties of interfaces. In Proceedings of the International SPIN Workshop on Model Checking of Software, Toronto, ON, Canada, 19–20 May 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 102–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffar, J.; Maher, M.J. Constraint logic programming: A survey. J. Log. Program. 1994, 19, 503–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroid, P.; Levin, M.Y.; Molnar, D.A. Automated whitebox fuzz testing. In Proceedings of the NDSS, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–13 February 2008; Volume 8, pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.; Brumley, D.; Yin, H.; Caballero, J.; Jager, I.; Kang, M.G.; Liang, Z.; Newsome, J.; Poosankam, P.; Saxena, P. BitBlaze: A new approach to computer security via binary analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems Security, Hyderabad, India, 16–20 December 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, V.T.; Böhme, M.; Santosa, A.E.; Căciulescu, A.R.; Roychoudhury, A. Smart greybox fuzzing. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2019, 47, 1980–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villoth, J.P.; Zivkovic, M.; Zivkovic, T.; Abdel-salam, M.; Hammad, M.; Jovanovic, L.; Simic, V.; Bacanin, N. Two-tier deep and machine learning approach optimized by adaptive multi-population firefly algorithm for software defects prediction. Neurocomputing 2025, 630, 129695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshniat, N.; Jamarani, A.; Ahmadzadeh, A.; Haghi Kashani, M.; Mahdipour, E. Nature-inspired metaheuristic methods in software testing. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 1503–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Lei, Y.; Lin, B.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Mao, X. Peculiar: Smart contract vulnerability detection based on crucial data flow graph and pre-training techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 32nd International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE), Wuhan, China, 25–28 October 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Akkem, Y.; Biswas, S.K.; Varanasi, A. A comprehensive review of synthetic data generation in smart farming by using variational autoencoder and generative adversarial network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.W.; Ko, J.S.; Huh, J.H.; Kim, J.C. Review on generative adversarial networks: Focusing on computer vision and its applications. Electronics 2021, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angluin, D. Queries and concept learning. Mach. Learn. 1988, 2, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrees, A.; Awan, H.H.; Javed, M.F.; Mohamed, A.M. Prediction of water quality indexes with ensemble learners: Bagging and boosting. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 168, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetnik, V.; Wang, T.; Tong, C.; Liaw, A.; Sheridan, R.P.; Song, Q. Boosting: An ensemble learning tool for compound classification and QSAR modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divina, F.; Gilson, A.; Goméz-Vela, F.; García Torres, M.; Torres, J.F. Stacking ensemble learning for short-term electricity consumption forecasting. Energies 2018, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Lyu, M.R. Benchmarking the capability of symbolic execution tools with logic bombs. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2018, 17, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Koutník, J.; Steunebrink, B.R.; Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A search space odyssey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Alves-Foss, J. The darpa cyber grand challenge: A competitor’s perspective. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2015, 13, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, G.; Lv, S.; Li, Z.; Sun, L. Concrete constraint guided symbolic execution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 46th International Conference on Software Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–20 April 2024; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshitaishvili, Y.; Wang, R.; Salls, C.; Stephens, N.; Polino, M.; Dutcher, A.; Grosen, J.; Feng, S.; Hauser, C.; Kruegel, C.; et al. Sok:(state of) the art of war: Offensive techniques in binary analysis. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).